Comparative Study for the Percutaneous Technique Vs. Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery for the Treatment of Pyelic Lithiasis

Alessandro Vengjer<1* and Marcos Tobias Machado2

1 Department of Urology, School of Medicine of ABC, Brazil

1 Head of the Uro-Oncology Sector of FMABC and researcher at FMABC, Brazil

Submission: May 07, 2018; Published: June 08, 2018

*Corresponding author: Alessandro Vengjer, Department of Urology, School of Medicine of ABC, Brazil, Tel:5513981329951; Email: alvengjer@uol.com.br

How to cite this article:Alessandro V, Marcos T M. Comparative Study for the Percutaneous Technique Vs. Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery for the Treatment of Pyelic Lithiasis. JOJ uro & nephron. 2018; 5(4): 555668. DOI: 10.19080/JOJUN.2018.05.555668

Abstract

Introduction: The standard treatment for pelvic lithiasis with calculi larger than 2cm is Percutaneous Nephrolithotripsy (PCNL); however, in selected cases laparoscopic treatment may have advantages. The single portal technique (LESS) is an option putatively associated to an additional reduction of morbidity, when compared to conventional laparoscopy. Objective: To compare the techniques of single-portal pelvicolithotomy vs. percutaneous nephrolithotripsy for the treatment of pyelic lithiasis.

Methods: We compared the prospective results of 10 sequential cases submitted to LESS pelvicolithotomy with 40 cases of (PCNL) for the same indication and calculus size.

Results: The mean surgical time was significantly higher at 162min for LESS vs. 115min for PCNL (p=0.02). The estimated mean bleeding was significantly lower (p< 0.01) with LESS (hemoglobin variation range: 0.3 and 0.9g/dL) vs PCNL (0.3 to 8.7g/dL). No transfusions were required for LESS cases, while 2 PCNL cases were transfused (p=0.31). No other severe postoperative complications were identified in either group. Similar mean hospital time were observed. Residual calculi occurred in 2 cases of PCNL but not in LESS (p=0.16). No second procedure was required after LESS, whereas one was required after PCNL.

Conclusion: LESS surgery is a therapeutic option and may be an alternative to PCNL in selected cases, especially if it is validated by multicentric studies with larger samples.

Keywords: Kidney Calculi; Laparoscopic; Percutaneos; Nephrolitothomy; Urolithiasis

Abbreviations: LP: Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy; PCNL: Percutaneous Nephrolithotripsy; RIRS: Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery; SWL: Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy; RLP: Retroperitoneal Pyelolithotomy; LESS: Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery; PUJ: Pelviureteric Junction.

Introduction

Renal lithiasis is one of the most common benign urologic diseases [1]. Due to the development endourological techniques, surgery for renal and ureteral lithiasis has all but disappeared. Such surgical procedures are well tested and developed techniques, over many years. However, they are invasive and result in very poor aesthetic and functional results; the required lumbotomy often result in chronic pain, incisional hernia, muscular flaccidity and long periods away from work. Endourological surgery has made important advances in recent years, but even so, in some situations, they do not offer complete or totally safe solutions. Among these, the Percutaneous Nephrolithotripsy (PCNL) which (according to the 2015 EAU Guideline) is the preferred technique for large pyelic calculi (>2cm); [2] however, it may not be so adequate for cases of anatomical abnormalities and very large volume calculi [3].

Percutaneous Nephrolithotripsy (PCNL) was first reported by Fernstrom & Johansson [4] and subsequently, it was established as a technique routinely used to treat patients with large or complex calculi [5].

Even when performed by experienced urologists, the PCNL procedure may lead to severe complications, which can occur in 7% of patients as well less serious complications in 25% of cases [6]. Bleeding is the most important complication, with reported transfusion rates of ranging from 1% to 10% of patients. Bleeding from an arteriovenous fistula or pseudoaneurysm requiring angiography and embolization occurs in less than 1% of patients [7]. Postoperative infectious complications are found in nearly 25% of patients due to injury of adjacent organs (intestine, spleen), failure to access the target and perforation of the renal pelvis and/or the ureter. The need for conversion to open surgery is rare. The mortality rate of PCNL is between 0.03% and 0.8% [8]. Colon injury is an uncommon complication (1%).

Laparoscopy

The gap left open by difficulties or risks of open technique and endoscopic surgeries has been filled by laparoscopy, a technique that aims to replace classic pelvic lithotomy through lombotomy in cases where open surgery is indicated. In Europe and the United States, open surgeries for urinary calculi are only indicated for cases of large and hard stones, following the failure of extracorporeal lithotripsy, percutaneous nephrolithotripsy or ureterolithotripsy, or even in cases of anatomical abnormalities [9,10].

Pelvic calculi can be treated by PCNL or laparoscopy, the latter allowing for the complete calculus removal without fragmentation, preventing damage of the renal parenchyma; it also allows the treatment of other associated diseases such as Pelviureteric junction (PUJ) stenosis [11].

The use of laparoscopy for the treatment of upper urinary tract lithiasis was first reported in 1992 by Raboy et al. [12] However, it was Goel & Hernak [13] who compared the open and laparoscopic techniques of ureterolithotomy, concluding that they were similar in result. In terms of pain, bleeding, hospitalization time and return to normal activities, laparoscopy was reported as the better procedure.

The Single Port Pyelolithotomy (LESS) technique for the treatment of proximal lithiasis was first described in 2008 by Rane et al. [14] Other studies showed the possibility of using a home-made Single Port device, using a glove and an Alexis retractor [14,15] as an alternative. The first description of a series of LESS was performed by our group and presented at the Brazilian Congress of Urology of 2015 [16].

Because no comparisons between PCNL and LESS have been reported, the objective of this study was to compare our initial experience in LESS with PCNL data for the treatment of large (>2cm) calculi. This study aims to compare percutaneous surgery and single-portal pyelolithotomy in terms of

i. Efficacy and

ii. Perioperative morbidity.

Materials and Methods

Study sample

The present study consisted of 50 patients, 10 of whom underwent surgical treatment using the Single Port Laparoscopic Pyelolithomy (LESS) technique, consisting of our initial experience with this method and paired with 40 patients from our institution submitted to Percutaneous Nephrolithotripsy (PCNL), to compare possible complications relating to these techniques. We specifically selected patients which presented exclusively pyelic calculi. Different single portal approaches were used in different cases according to the best strategy to establish access in each case. Strategy also defined whether conventional laparoscopic or minilaparoscopic tweezers were used

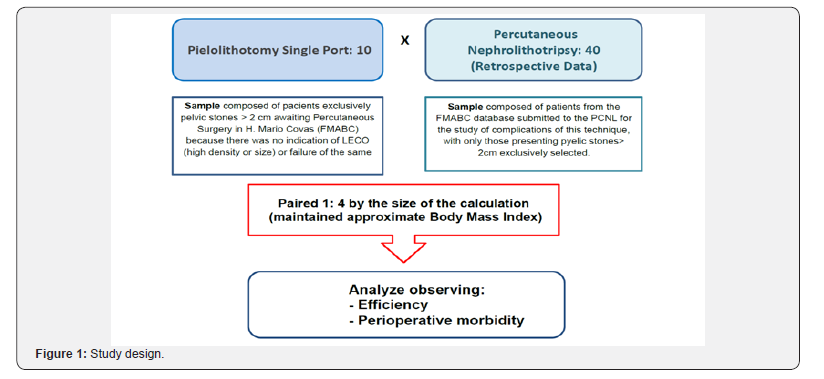

Cases were matched by similarity in size of the calculi, 1 case of LESS matching 4 cases of PCNL. Body mass index was paired as closely as possible, as shown in Figure 1. Residual calculi were defined as larger than 4mm and/or symptomatic and/or generators of dilatation.

Inclusion criteria

In the study for LESS, individuals with pyelic lithiasis greater than 2 centimeters who had an indication of PCNL as a function of size and/or density of the calculus and those who failed treatment with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) were randomly selected from those awaiting the completion of PCNL at the Hospital Mario Covas, linked to ABC Medical School, in São Paulo, Brazil. The study included male and female patients at least 18 years old, regardless of race, creed, education or marital status. Only patients who understood and accepted the study conditions and signed the informed consent form were included. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Exclusion criteria

The following conditions resulted in exclusion:

a. Patients undergoing previous surgical treatments for lithiasis;

b. Patients with formal contraindications to the surgical/ laparoscopic procedure, especially those with COPD/CHF and coagulopathies.

Evaluation criteria

We evaluated the differences in results between the two techniques considering:

a. Efficacy evaluated as rate of patients free of calculus after tomographic control, length of hospital stay and surgical time;

b. Perioperative morbidity evaluated through transfusion rates, hemoglobin differences and complications,

Surgical technique for LESS

Patients were submitted to general anesthesia, a double J catheter was implanted after ureteroscopy, followed by placement of a bladder catheter; the patient was then repositioned to a lateral decubitus and the bladder catheter was placed contralaterally to the surgical side as shown in (Figure 2).The single portal was installed through a cutaneous incision and posterior divulsion of the muscular planes with access to the retroperitoneum. In eight cases, the Alexis retractor was coated with a surgical glove (Figure 3). Laparoscopic tweezers were Mini Storz (Figure 4) and, in some cases, conventional laparoscopic tweezers. In two cases, we used the Single Storz Portal (Figure 5) and minilaparoscopy tweezers (5mm optics and 3mm tweezers). In one case, we inserted the Single Taimin Portal; however, because of gas leakage, it was replaced by the Alexis Retractor with a surgical glove with conventional clamps; in two cases, we used a 3mm auxiliary portal. After access and installation of the portal, the structures of the retroperitoneal compartment were identified, and a pelvic incision was made to access the calculus, which was removed from the cavity, followed by pelvic suture. All 10 LESS procedures were performed by a single surgeon with extensive experience in laparoscopy.

Surgical technique for PCNL

Patients were submitted to general anesthesia, positioned for lithotomy with insertion of a ureteral catheter, with posterior modification of the decubitus to ventral. Pyelography was performed by the ureteral catheter and 18G needle puncture, followed by dilatation with Amplatz up to 30 Fr, leading to renal access by rigid nephroscopy (no flexible nephroscope was used) with identification of the calculus. Fragmentation was performed with ultrasound lithotripsy and removal of the fragments with trident forceps, followed by double J catheter implantation and nephrostomy. All 40 PCNL procedures were performed by a single experienced surgeon in the Urolithiasis Sector of the institution.

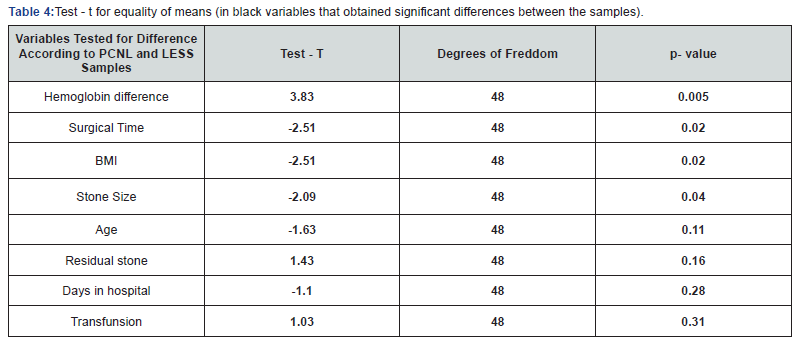

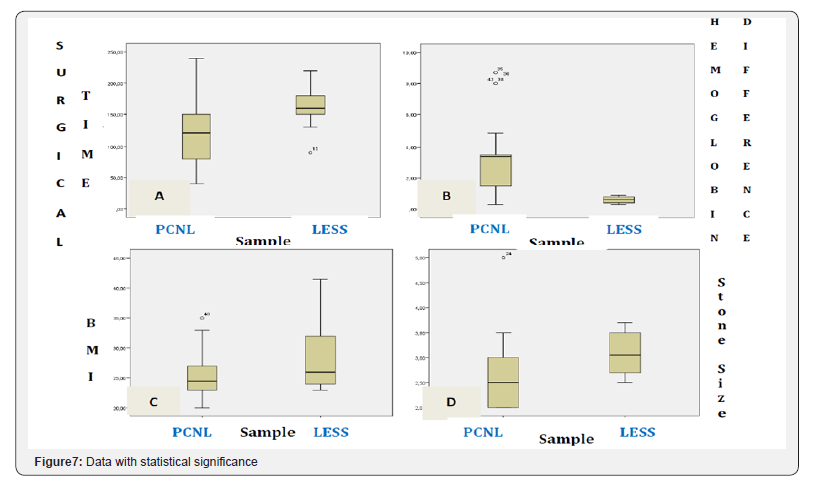

Statistical analysis

Paired t-tests were used to test the mean difference of all variables between the PCNL and LESS samples. Box-Plot graphs were used to demonstrate the observed differences.

Results

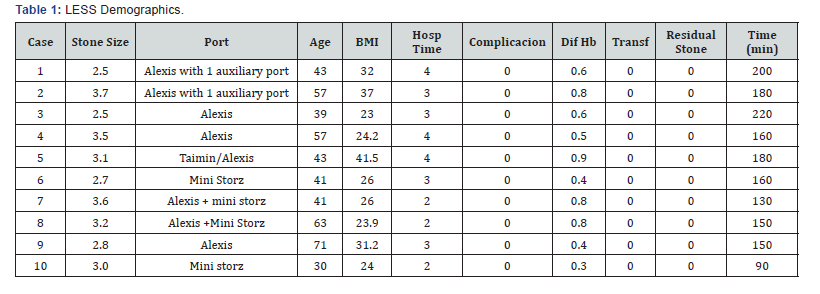

The analysis was made using the data obtained in the 10 LESS procedures and in the 40 PCNL procedures. We considered size of the calculi, age, body mass index, hemoglobin and hematocrit, pre-and post-operative time, length of hospital stay, complications according to the Clavien-Dindo scale [17], number of blood transfusions, surgical time, need for second procedure and residual calculi. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the LESS group.

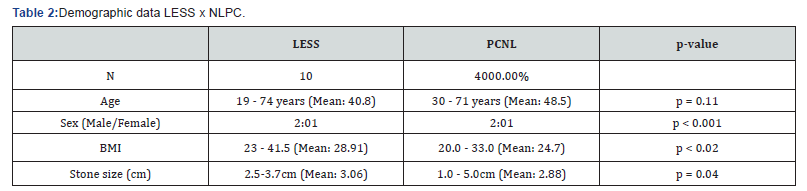

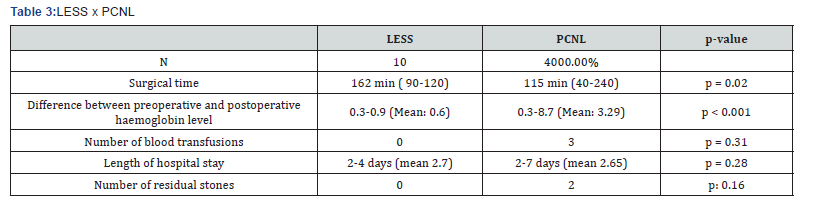

Calculus size ranged from 2.5 to 3.7cm (mean: 3.06cm) for LESS vs. 2 to 5cm (mean: 2.88) for PCNL. Regarding age, patients age ranged between 30 and 71 years (mean: 48.5 years) in for LESS vs. 19 and 74 years (mean: 40.8 years) for PCNL; BMI ranged 23 to 41.5kg/m2 (mean: 28.91kg/m2) in LESS vs. 20 and 33kg/m2 (mean: 24.7kg/m2) for PCNL as shown in Table 2. Significantly smaller reductions (p< 0.01) occurred pre to postoperative Hb in LESS (from 0.3 to 0.9g/dL - mean: 0.6g/dL) vs. PCNL (0.3g to 8.7g/dL - mean: 3.29g/dL). Length of stay: 2 to 4 days (mean: 2.7 days) for LESS vs. 2 to 7 days (mean: 2.65 days) for PCNL. With respect to complications, all LESS cases presented grade I of Clavien-Dindo [17]. For PCNL, three cases (7.5%) presented grade II of this scale, due to the need of blood transfusions. There were no cases of transfusion in LESS vs. two cases in PCNL. The duration of the procedure was significantly higher (p=0.02) for LESS (162 minutes - range: 90 to 220min) vs. PCNL (115 minutes - range: 40 to 240min), as shown in Table 3. Complementary procedures were not necessary for LESS (no residual calculi), vs. two cases (5%) of residual calculi in the PCNL patients. Functional and cosmetic results, shown in Figure 6 were quite satisfactory for both procedures.

Statistical analysis showed statistically significant differences for Hb (better for LESS), surgical time (shorter for PCNL); no significant differences were found for BMI, size of the calculi, age, residual calculi, time of hospitalization or transfusions (Table 4), which may be visually inspected in Figure 7 & 8.

Discussion

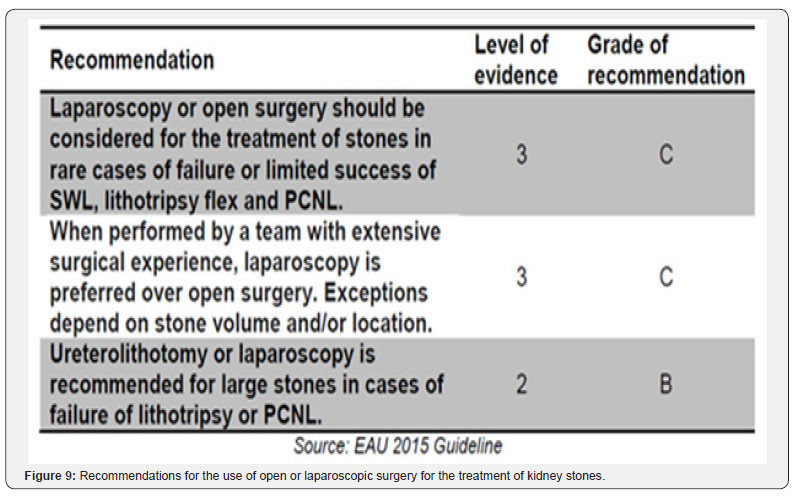

The 2015 EAU Guideline2 indicates that kidney stones larger than 2 centimeters may be treated either with SWL or PCNL (degree of recommendation B); however, larger calculi have a degree of recommendation A for PCNL. In this guideline, laparoscopy may be an alternative for cases of PCNL failure (Figure 9). Thus, laparoscopy has been tried [18,19] and compared to PCNL [20,21], which is considered the gold standard.

Because there are no articles evaluating Single Port for Pyelolithotomy vs. other techniques, we used LP data with multiple portals for comparison in this series.

In this study we examined and compared two general aspects: efficacy and perioperative morbidity. In these two aspects, factors such as age, sex, BMI and calculus side did not exhibit significant differences [2].

Case A

We considered the following data.

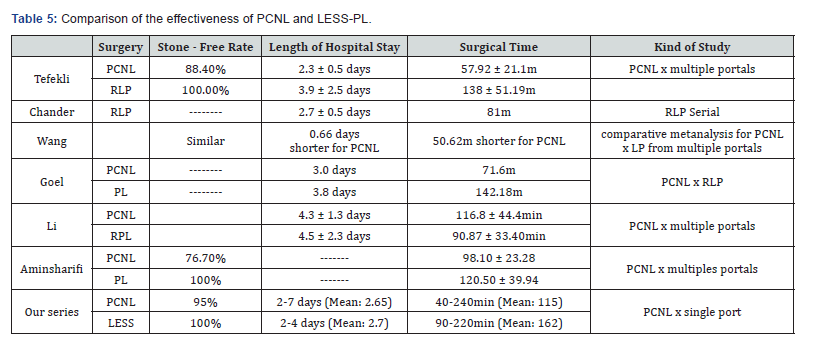

Calculus-free rates: we obtained 100% and 95% rates for LESS and PCNL, respectively. Equivalent results were found by Tefleki et al. [22] with 100% free stone for RLP and 88.4% for PCNL. The efficacy of the laparoscopic route is largely a consequence of the fact that calculus removal is performed without its fragmentation, thus preventing residual fragments to be left behind [2], as shown in Table 5.

Surgical time: most authors who have studied this factor agree that PCNL presents a shorter operative time [22,23], which was also observed in our series. This has also been described by Wang et al. [21] in his meta-analysis. In contrast, Li et al. [20] recorded shorter procedure duration with RLP, as also shown in Table 5.

Hospitalization time: Many authors report a longer PCNL time [18,22,24], including the Wang et al. [21] metanalysis with 7 trials totaling 176 and 197 multiport LP and PCNL patients, respectively. Nambirajan et al. [24] included multiple renal calculi and situations in which there was concomitant PUJ stenosis, with observed hospitalization time between 5 and 35 days. Goel & Hemak [25] reported lengths of hospital stay of 3.8 days for RLP versus 3 days for PCNL. However, Li et al. [20] in a comparative randomized study, found no differences between hospitalization time of PCNL vs. Laparoscopy, as we also observed in our series (2.7 for LESS x 2.65 for PCNL); this is also shown in Table 5.

Unfavorable anatomical situations: Some reports [22,26] point out the possibility of using Laparoscopy in cases of ectopic kidneys or other anomalous formations, with better results vs. PCNL. In 1997 Harmon et al. [27] reported the first case in which a 2.5cm pyelic calculus was completely removed from an ectopic kidney through a laparoscopic procedure. Later, Ramakumar et al. [26] described another case of ectopic kidney pyelolithotomy.

Regarding the efficacy for the removal of a single stone, we believe our study shows that Laparoscopy by single or multiple portals presented similar rates of stone-free outcomes, superior to what was obtained through PCNL, with only slightly higher surgical duration.

Perioperative morbidity (Complications)

lPCNL has its well-established complication rates: the 2015 EAU Guideline reported 7% transfusion rates, 0.5% sepsis, 0.4% need for embolization and 0.5% rate of mortality [2]. Such risks are substantially minimized in the comparisons between PCNL and Laparoscopy, because the latter does not perforate the renal parenchyma [19,20,22].

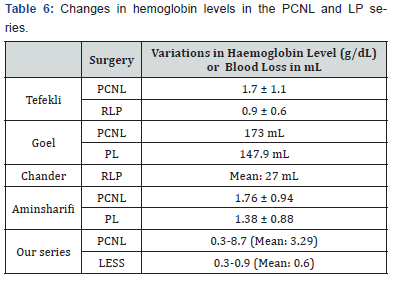

Transfusion: recently, a multicenter study (CROES) with 5803 patients evaluated complications of PCNL showing a transfusion rate of 5.7% and fever in 10.5% of cases [28]. Regarding hemoglobin loss, Tefekli et al. [22] noticed pre and postoperative variation of 0.9 ± 0.6g/dL and 1.7 ± 1.1g/ dL, respectively, for RLP and PCNL. Chander et al18 reported an average blood loss of 27 mL in his RLP series; Wang et al. [21] reported a smaller drop in hemoglobin levels in LP, while Ramakumar et al. [26] described a blood loss of less than 145mL. Goel & Hemak [25] reports bleeding of 147.9mL for RLP versus 173.1mL for PCNL. Aminsharifi et al. [23] observed no difference in hemoglobin fall. We found a significantly lesser hemoglobin decrease for LESS, which is consistent with other reports [20,21] as shown in Table 6.

Others complications: fever was found less frequently in LP (3.4% in RLP versus 13.5% in PCNL) [20], and this was also demonstrated by Wang et al. [21]. In our series of LESS, postoperative fever never occurred.

Urinoma, conversion or transfusion were reported by Lee et al. [19] in only 1 case out of 77 studied. In our cases, none of these occurred. Goel et al. [25] reported the need for conversion in two cases, due to the peri-pyelic adhesion of a solitary (>3cm) stone. We emphasize that such adherence was found in all of our cases, although it did not prevent the procedure to be successfully completed. We did not objectively evaluate factors with renal pelvis characteristics (extra or intra renal).

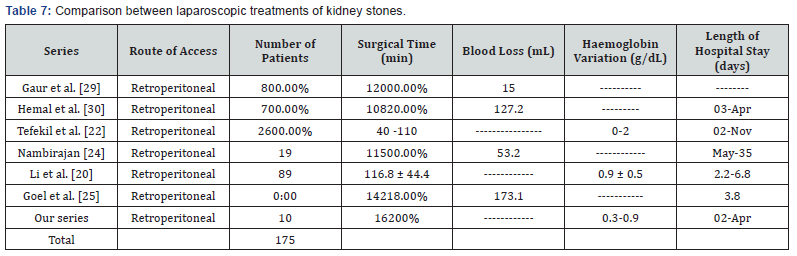

Table 7 presents data from several studies [20,22,24,25,29,30], which we compared to our series. Regarding postoperative morbidity/complications, we observed that the Single Port or Multiport Pyelolithotomy presented less complications with respect to hemoglobin variation, urinoma and postoperative fever. It should be pointed out that reports indicate that there may be technical difficulties due to peri-pyelo inflammatory adhesions, with a variable conversion rate of 0 to 12% [17,20].

Our study has limitations:

a. We compared our LESS data to a retroactive series of PCNL;

b. Our sample sized (10 cases) is small;

c. We did not evaluate the retrospective cases series (PCNL) nor our limited experimental sample (LESS) using the AST (American Society Anesthesiology) standards for such evaluation;

d. We did not evaluate the impact of using different single portals nor the different types of renal pelvis presentation.

This comparative series of PCNL and LESS cases is an initial experience and we believe it will stimulate studies with larger, controlled and randomized series such as those described for multiple portals LP which is a more established and tested procedure to turn LESS into a more thoroughly studied procedure contributing to its validation as an alternative technique.

Based on the evidence presented here, it may be concluded that LESS can be seen as an alternative technique to PCNL in special situations, because it presents

a. Good efficacy (high free rate of calculi, combined with a slightly longer time of surgery) and

b. Low perioperative morbidity, bleeding rate, low rate of complications, and surgical conversion. However, these data should ideally be confirmed by controlled, multicenter studies performed with larger numbers of included patients.

References

- Saltirov, T Petkov, K Petkova (2010) Current trends in the treatment of ureterolithiasis: Our 10 years experience with endoscopic and minimally invasive treatment modalities. Eur Urol Suppl 9: 578.

- Turk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, Seitz C, Skolarikos A, et al (2015) EAU Guidelines on Intervential Treatment for Urolithiasis. Eur Urol 69(3): 475-482.

- Hurza M, Schulze M, Teber D, Gozen AS, Rassweiler JJ (2009) Laparoscopic techiniques for removal of renal and ureteral calculi. J Endourol 23(10): 1713-1718.

- Fernstrom I, Johansson B (1976) Percutaneous pyelolithotomy: a new extraction technique. Scan J Urol Nephrol 10(3): 257-259.

- Segura JW, Patterson DE, Le Roy AJ, McGaugh PF, Barrett DM (1982) Percutaneous removal of kidney stones. Mayo Clin Proc 57: 615.

- Preminger GM, Assimos DG, Lingeman JE, Nakada SY, Pearle MS, et al. (2005) Chapter 1: AUA guideline on management of staghorn calculi: diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol 173(6): 1991-2000.

- Keoghane SR, Cetti RJ, Rogers AE, Walmsley BH (2013) Blood transfusion, embolization and nephrectomy after percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). BLU Int 111(4): 628-632.

- Lee WJ, Smith AD, Cubelli V, Badlani GH, Lewin B, et al. (1987) Complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 148(1): 177-180.

- De la Rosette J, Assimos D, Desai M, Gutierrez J, Lingeman J, et al. (2011) The clinical research office of the endourological society percutaneous nephrolithotomy global study: indications, complications and outcomes in 5803 patients. J Endourol 25(1): 11-17.

- Kramer BA, Hammond L, Schwartz BF (2007) Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy: indications and technique. J Endourol 21(8): 860-861.

- Saussine C, Lechevallier E, Traxer O (2008) Urolithiasis and laparoscopic. Treatment of renal stones in special anatomical and functional conditions. Prog Urol 18(12): 948- 951.

- Raboy A, Ferzli GS, Ioffreda R, Albert PS (1992) Laparoscopic ureterolitothotomy. Urology 39: 223-225.

- Goel A, Hernal AK (2001) Upper and mid-ureteric stones: A prospective unrandomized comparision of retroperitoneoscopic and open ureterolithotomy. BJU Int 88(7): 679-682.

- Rane A, Rao P (2008) Single-port-acess nephrectomy and other laparoscopic urologic procedures using a novel laparoscopic port (R-port). Urology 72(2): 260-264.

- Jeon HG, Jeong W, Oh CH, et al. (2010) Inicial experience with 50 laparoendoscopic single site surgeries using a homemade, single port device at a singles center. J Urol 183: 1866-1871.

- Vengjer A, Machado MT, Silva JL, Silva IN, Pompeo ACL (2015) LESS pielolitotomia x percutânea para o tratamento do cálculo piélico.In XXV Congresso Brasileiro de Urologia, Rio de Janeiro.

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) The Clavien Dindo Classification of Surgical Complications. Ann Surg 244(2): 931- 937.

- Chander J, Suryavanshi M, Lal P, Singh L, Ramteke VK (2005) Retroperitoneal Pyelolithotomy for Management of Renal Calculi. JSLS 9(1): 97-101.

- Lee JW, Cho SY, Yeon JS, Jeong MY, Son H, et al. (2013) Laparoscopic Pyelolothotomy: Coparisio of Surgical Outcmes in Relation to Stone Distribuition Within the Kidney. J Endourol 27(5): 592-597.

- Li S, Lui TZ, Wang XH, Zeng XT, Zeng G, et al. (2014) Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Retroperitoneal Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy Versus Percutaneous Nepholithotomy for the Treatment of Large Renal Pelvi Calculi: A Pilot Study. J Endourol 28(8): 1-5.

- Wang X, Li S, Liu T, Guo Y, Yang Z (2013) Laparocopic pyelolithomy compared to percutaneous nepholitothomy as surgical managment for larger pelvic calculi: A metanalysis. J Urol 190(3): 888-893.

- Tefekli A, Tepeler A, Akman T, Akçay M, Baykal M, Karadag MA, et al. (2012) The comparision of laparoscopic pyelothotomy and percutaneous nepholithotomy in the treatment of solitary large renal pelvic stones. Urol Res 40: 549-555.

- Aminsharifi A, Hosseini MM, Khakbaz A (2013) Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy for a solitary renal pelvis stone larger than 3cm: a prospective cohort study. Urolithiasis 41(6): 493-497.

- Nambirajan T, Jeschke S, Albqami N, Abukora F, Leeb K, et al. (2005) Role of laparoscopiy in management of renal stones: single-center experience and rewiew of literature. J Endourol 19(3): 353-359.

- Goel A, Hemal AK (2003) Evaluation of role of retroperitoneoscopic pyelolithotommy and its comparision with percutaneous nepholithotripsy. Int Urol Nephrol 35(1): 73-76.

- Ramakumar S, Lancini V, Chan DY, Parsons JK, KavoussiLR, et al. (2002) Laparoscopic pyeloplasty with concomitant pyelolithotomy. J Urol 167(3): 1378-1380.

- Harmon WJ, Kleer E, segura JW (1996) Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy for calculus removal in a pelvic kidney J Urol 155(6): 2019- 2020.

- De la Rosette J, Assimos D, Desai M, Gutierrez J, Lingeman J, et al. (2011) On behalf of the CROES PCNL Study Group. The clinical Research office of the endouological society percutaneous nefpholithotomy global study: Indications, Complications, and Outcomes I 5803 patients. J endourol 25(1): 11-17.

- Gaur DD, Agarwal DK, Purohit KC, Darshne AS (1994) Retroperitoneal laparoscopic pyelolithotomy. J Urol 151(4): 927- 929.

- Hemal AK, Goel A, Kumar M, Gupta NP (2001) Evaluation of laparoscopic retroperitoneal surgery in urinary stone disease. J Endourol 15(7): 701-705.