Patients' Evaluation of an Educational and Training Experiential Intervention (ETEI) to Enhance Treatment Decision and Self-Care Following the Diagnosis of Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer

Nihal E Mohamed1*, Sailaja Pisipati2, Mario Cassara3, Sarah Goodman3, Cheryl T Lee4, Cynthia J Knauer RN1, Reza Mehrazin1, John P Sfakianos1, Barbara Given5, Diane Z Quale6 and Simon J Hall7

1Department of Urology and Oncological Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, USA

2University of Nevada Reno School of Medicine, USA

3Department of Public Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, USA

4Department of Urology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, USA

5College of Nursing, Michigan State University, USA

6Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network, USA

7Smith Institute for Urology, North Shore/LIJ Health System, USA

Submission: October 30, 2017; Published: November 21, 2017

*Corresponding author: Nihal E Mohamed, Department of Urology and Oncological Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine, USA, Tel: (212) 241-8858; Email: nihal.mohamed@mountsini.org

How to cite this article: Mohamed N, Pisipati S, Cassara M, Goodman S, Lee C T et al. Patientsí Evaluation of an Educational and Training Experiential Intervention (ETEI) to Enhance Treatment Decision and Self-Care Following the Diagnosis of Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. JOJ uro & nephron. 2017; 4(2): 555635. DOI:10.19080/JOJUN.2017.04.555635

Abstract

Objectives: This study examines patients' evaluation of an educational and training experiential intervention (ETEI) developed to enhance muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) patients' treatment decision-making and post-treatment self-care.

Methods: Participants were recruited from the Mount Sinai Medical Center and via the National Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network website between December, 2011 and September, 2012. Data were collected via individual interviews and electronic medical record review. Qualitative analysis of patients' reaction and evaluation of the proposed content of the ETEI modules was performed.

Results: Data were collected for a total of 30 study participants (26.7% women; 93.0% non-Hispanic White) who underwent cystectomy and urinary diversion for MIBC. Mean age was 66.6 years. 50%, 43.3% and 6.7% of patients were treated with ileal conduit, neobladder and continent reservoir respectively. High satisfaction rate with the educational and training components was reported.

Conclusion: The study results emphasize the importance of the proposed ETEI and appropriateness of the informational and training modules for both patients and their caregivers. Such an intervention will help reduce the burden of care on patients, care-givers and care- providers.

Keywords: Urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder; Muscle invasive bladder cancer; Radical cystectomy; Urinary diversion; Unmet need; Educational and training experiential intervention

Abbreviations: BC: Bladder Cancer; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; MIBC: Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer; RC: Radical Cystectomy; UD: Urinary Diversion; CCD: Continent Cutaneous Diversion; QoL: Quality of Life; ETEI: Educational and Training Experiential Intervention; BCAN: Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network's; IRB: Institutional Review Board; ACS: American Cancer Society; SRT: Self-Regulation Theory

Practice-Implications

There could potentially be an increased need for resources -educational booklets, audio-visuals, trained health care personnel, length ± number of appointments.

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is the fifth most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States (US). According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, it is estimated that 79,030 new cases of BC will be diagnosed in 2017 and 16,870 patients die of this disease [1]. There has been a decreasing trend in mortality from BC in the US and Europe [2,3], possibly reflecting reduced occupational exposure to carcinogens, reduced incidence of smoking and improved standard of care [4,5].

25% of the newly diagnosed cases of BC are muscle invasive requiring aggressive radical surgery or radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy [6]. The outcomes, however, remain poor despite aggressive systemic treatments [7,8]. Muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is a potentially lethal malignancy and continues to pose an enormous challenge, especially in older patients. The current standard of care for non-metastatic MIBC is radical cystectomy (RC) with lymphadenectomy, followed by urinary diversion (UD) to either a cutaneous stoma or the existing urethra, thus providing excellent local control [9-13]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been proven to enhance survival outcomes in MIBC by eliminating residual disease, although it is not exempt from side-effects [14].

The three methods of UD currently used are incontinent diversion with a stoma (e.g., ileal conduit, IC), orthotopic continent UD (e.g., neobladder), and continent cutaneous diversion (CCD, e.g., Indiana pouch) [15]. Each of these procedures is associated with a distinct set of challenges and complications, as well as unique psychological burdens [9-13]. The neobladder most closely resembles the native bladder and preserves continence, reducing the need for regular longterm intermittent catheterization associated with CCD [16]. The IC presents shorter recovery time and is largely free of the metabolic complications associated with the orthotopic neobladder procedure. However, the IC requires the use of a stoma and urine collection bags, which patients may find upsetting and obstructive to post-operative lifestyle [16].

RC with UD is associated with high surgical morbidity and mortality [17,18]. Although the incidence there of has declined, severe complications remain a great concern to 30% of patients during in-hospital stay, and to 60% of patients within 90 days of surgery [17-26], thereby resulting in prolonged length of hospital stay and negatively impacting recovery [27, 28]. Careful maintenance of the surgical and UD sites is integral to promoting recovery and restoring urinary function. Surgeons must also refine pre- and postoperative strategies to enhance patient recovery following cystectomy. Emphasis must be placed on improving pre-operative nutritional status, educating patients about red-flag symptoms, enhancing recovery protocols, counseling patients, setting realistic goals and expectations, and training patients regarding stoma care [29-32].

RC and UD procedures can significantly alter patients' quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial adjustment. Reduced sexual potency and urinary incontinence are recurring issues, often directly attributable to the diversion process itself [33]. Moreover, no UD technique is clearly better in terms of post-operative QoL and psychosocial adjustment. Preference for a certain procedure is largely based on patient-specific characteristics such as age, comorbidities, physical and manual dexterity, prospective surgical issues, and lifestyle needs [34,35]. Each type of diversion carries its own set of psychological burdens, including negative body image and intrusive nighttime awakenings [34-36]. Poor body image has shown to be more common among patients with conduits, which leads many newly diagnosed patients to opt for the neobladder despite the possibility of reduced urinary continence. Insecurities are mostly due to the stoma's appearance and required continuous care [34-36].

IC is associated with stomal difficulties (prolapse, retraction, stenosis, skin irritation, urinary leakage, difficulty in proper positioning and securing stomal appliance), renal deterioration, and recurrent urinary infections [37-40]. Furthermore, depending on the absorptive characteristics of different bowel segments used for reconstruction, IC diversion may lead to one of various metabolic abnormalities such as metabolic acidosis, hypochloremia, hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia. These metabolic derangments, however, are more of a concern with neobladder when compared to an IC. Additionally, neobladder requires lifelong monitoring including urethral surveillance, as well as frequent irrigation of the reservoir for mucus clearance. It also features a higher rate of nocturnal incontinence and metabolic disorders [39,41,42].

Patient-related factors play a significant role in determining the type of UD. For instance, elderly patients typically opt for a conduit, as the operation itself is relatively simpler and quicker than both orthotopic and continent reservoir reconstruction [43], and it minimizes incontinence issues. Gender also influences the selection of diversion type; fewer women are eligible candidates for the neobladder procedures due to increased chance of voiding dysfunction when compared to men [44]. Women also tend to require extensive individual evaluation prior to the procedure to ensure that the tumor is not located at the bladder neck and that there is a clear urethral margin at the time of cystectomy [17]. Patient preference further varies based on treatment-related values, expectations, cultural background, and socioeconomic status [45]. Preoperative continence can reasonably predict postoperative urinary function as preexisting urinary problems may worsen after the orthotopic neobladder procedure (e.g., preexisting urinary problems may predict or produce increased urinary incontinence and greater likelihood of intermittent catheterization).

Lastly, patient preference also plays an important role in procedure decisions. While IC might offer a less complicated method of bladder evacuation, its impact on body image and the possibility of urine leakage makes it less attractive especially for younger patients. The occasional leakage following the neobladder procedure may seem tolerable to those who fear the conduit's impact on body image and the associated urine collection bag and stoma care. Existing comorbidities (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, effects of prior radiotherapy) may preclude the use of the bowel for the neobladder, which leads some patients to opt for the IC [46-49]. Physician preference can also influence selection of UD type, as can surgeon-specific characteristics such as age, race, location of practice, surgical volume and surgeon preference [50,51].

The entire process of evaluating disease severity, navigating treatment options, recovering from surgery, and acclimating to postoperative lifestyle changes is undoubtedly rife with difficult and multifaceted decisions. Given the challenges both inherent and specific to MIBC, it is critical to ensure proper support for patients throughout each phase of diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. A recent study by Lee CT et al. [52], found that even among NCI-designated institutions, few treatment centers employ active BC support groups, survivorship clinics, or community resources for education and patient navigation [52]. Patients with MIBC usually receive post-operative educational support regarding self-care strategies such as the utility of stomal appliances and catheterization, yet there remains a lack of research on the actual decision-making process over the course of treatment, as well as on the possible benefits of more extensive educational support for patients prior to surgery. It is therefore critical to investigate BC patients' decision-making processes, which depend upon adequate, ongoing educational support.

In this context, our study evaluated the acceptability of an educational intervention that we developed to enhance MIBC patients' treatment decisions and QoL. Improved knowledge of how patients understand and approach their disease can better inform doctors’ care throughout the diagnosis and treatment process. This study therefore explores the merits of a certain BC educational program meant to both inform patients' decisionmaking and improve their long-term post-operative satisfaction.

Study Design

Study design and methods

This study evaluated patients’ acceptability and preliminary evaluation of an educational and training experiential intervention (ETEI), which was designed to enhance treatment decisions and postoperative QoL. Via individual, qualitative, semi-structured interviews, researchers gathered patients' information about unmet informational and supportive care needs both before and after MIBC treatment to inform the study’s overall design. They also conducted an extensive literature review to explore additional challenges and areas of need that MIBC patients experience across the disease trajectory [34, 36, 53, 54]. The research team conducted iterative reviews of the ETEI until agreeing upon the final version's content [55].

Description of the educational and training experiential intervention (ETEI)

The traditional model of Self-Regulation Theory (SRT), the Ottawa Decision Support Framework [56-58], results of the aforementioned in-depth interviews, literature, reviews, and other expert’s input each helped guide the development of the ETEI’s educational and training content.

a. Provide accurate information about MIBC treatment and diversion options;

b. Create realistic expectations;

c. Identify and explore values and goals to provide a context for making "preference sensitive" decisions and choices;

d. Provide emotional support, such as via validation of feelings and concerns

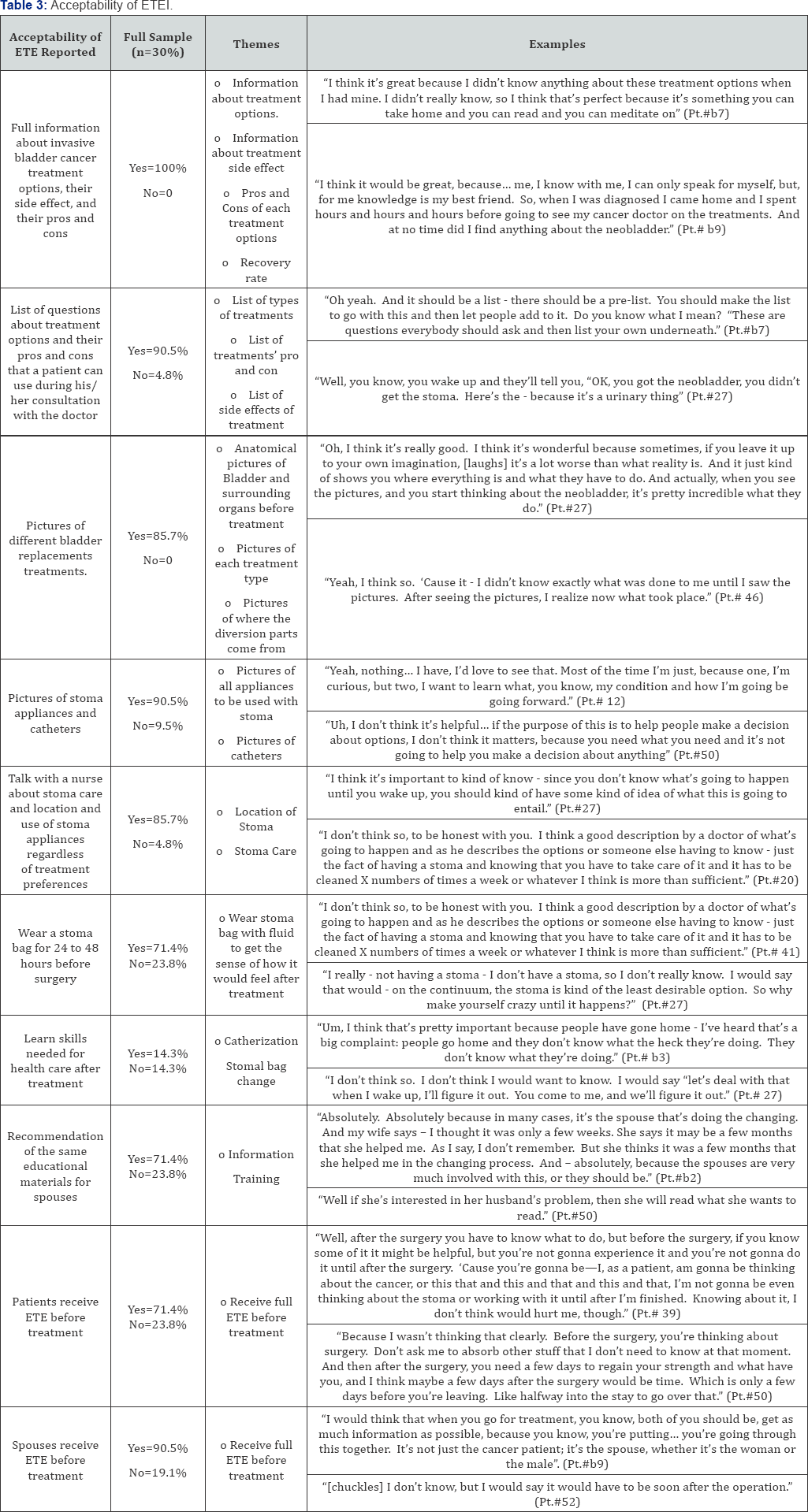

e. Provide information and tangible support to enhance skills needed for postoperative stoma and pouch care. Researchers intended that the ETEI’s educational components be delivered via a 1-hour nurse-led session and a follow-up call, both of which involved discussion of treatment options and patients’ concerns. Each patient also received four booklets describing each BC treatment option, respective self-care requirements associated with each treatment option, along with a question list for the doctor. The training component involves trying out a stoma bag filled with saline solution for about 24-48 hours to get a sense of how it feels to have an IC-related stoma (Table 3) [55].

Selection and recruitment of participants

Between January 2010 and January 2012, researchers recruited patients with MIBC at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Urology department. Eligible participants included patients between the ages of 18 and 85 who underwent RC and UD for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Patients with metastatic disease, cancer recurrence, or secondary cancers were excluded. Of the 35 eligible patients, 19 (54.28%) agreed to participate in the study. Reasons for declining to participate included lack of interest, limited time, and poor health condition. Patients were also recruited via the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network's (BCAN) online advertisement, which required the same eligibility criteria using self-reported medical information. All 11 of the BCAN advertisement respondents were eligible and agreed to participate. All study participants (N=30) consented and were compensated with a $50 gift card.

Ethical issues and approval

Patients provided verbal and written informed consent prior to each interview. Each received a detailed description of the study’s aim and the confidential nature of their responses. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of ISMMS and was funded by the American Cancer Society (ACS).

Data collection

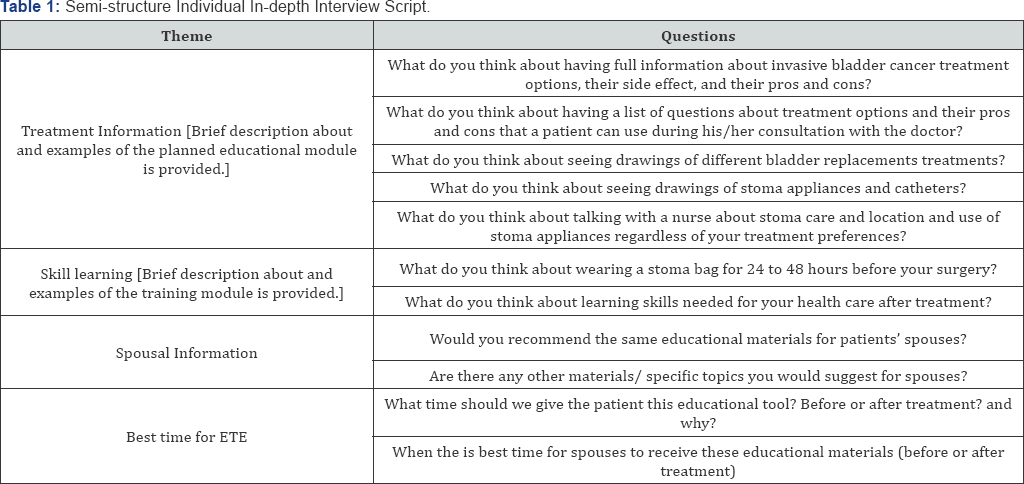

To facilitate informative discussions with patients about the ETEI’s content and acceptability, researchers developed a semi-structured interview guide using experts' opinions, as well as results of prior extensive reviews examining patients' and survivors’ unmet needs. [36]. Data were collected through in-person (N=9) or telephonic (N=21) interviews (median time: 60 minutes; range: 30-90 minutes), using a semi-structured interview guide (Table 1). To maintain uniformity, the same individual (NM) conducted all interviews. Plain language was used to explain all medical terminology. Study participants were asked 11 questions about the type of information and training they wished they had received beforehand, and the best times to have received them (Table 1). The coding guide identified narrative themes related to the ETEI's acceptability and patients’ evaluations thereof. The interview questions directly reflected the template and coding guide's thematic categories of treatment information, skill learning, spousal information, and best time for intervention.. The open-ended interview protocol allowed participants to narrate their experiences and views in broad personal detail. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, and a member of the research team made additional written notes. Data was coded during collection and completed upon saturation (i.e., when no new or relevant data emerged).

Data analysis

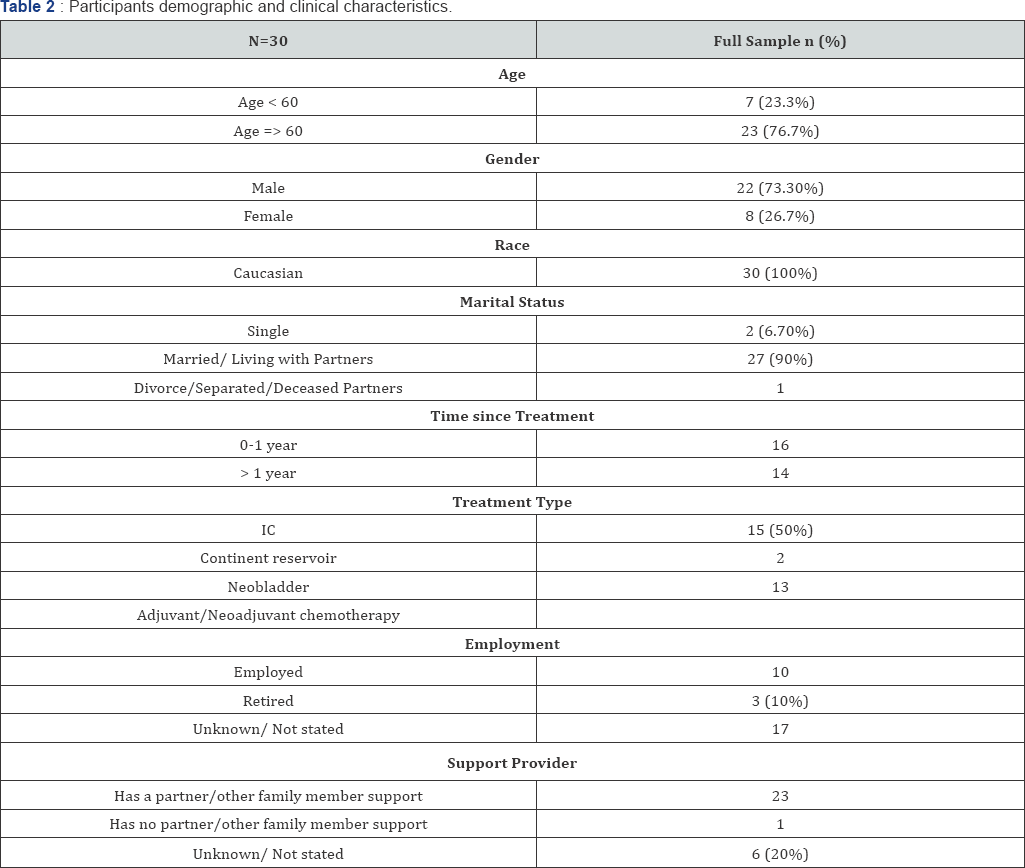

A qualitative analysis using the template analysis approach that involves developing a template/coding guide for sorting narrative data was employed. Content analysis of participants' responses using the template analysis approach also included checking for representativeness of the data, data triangulation (i.e. use of multiple methods to interpret data, such as comparing coding of interviews with written notes) and verification for external validity [59-61]. The coding guide identified narrative themes related to the ETEI's acceptability and patients' evaluations thereof. The interview questions directly reflected the template and coding guide's thematic categories of treatment information, skill learning, spousal information, and best time for intervention.. Group discussion and negotiation among the members of the research team helped resolve any conflicts regarding which codes should be assigned to certain clusters of data. All data were coded using Atlas.ti software [62]. We obtained ISSMS patients’ demographic data such as age, treatment date, and treatment type from medical charts to assist in analysis. For patients recruited from BCAN, we relied on patients’ self-reported infermation (Table 2).

Results

Data were collected for a total of 30 study participants (26.7% women; 93% non-Hispanic White) who underwent RC and UD for MIBC. Mean age was 66.6 years (range: 52-82; standard deviation [SD]=8.99). Half of the study population were treated with IC (50%, N=15), while 43.3% (N=13) were treated with neobladder and the remainder (6.7%, N=2) with the continent reservoir. Table 1 depicts study participants' demographics and clinical characteristics. Table 3 summarizes the results by depicting the acceptability of the ETEI modules. Overall, patients expressed high satisfaction with the educational and training components of the ETEI, as indicated by their reaction to proposed content and plans of intervention delivery.

The educational module of the ETEI: Treatment information

All participants (100%) desired substantial information about the various UD options available and their outcomes. All agreed that it would have been beneficial to receive full and comprehensive information about each UD option and its side effects, as described in the ETEI’s informational module. 90.5% believed they would have benefited from a prepared list of general questions describing and comparing treatment options during their consultations. 4.8% did not think such a list would have been useful, as they relied solely on their physician’s treatment recommendations unique to their situation. Moreover, 86.7 % expressed that viewing the ETEI's medical illustrations (or other similar visual representations of each treatment option) would have enhanced their preoperative understanding of how each UD procedure changes the urinary tract’s anatomy and functioning.

with90.5 % felt that seeing the ETEI’s pictures of stomal appliances and catheters would have helped them prepare for potential postoperative challenges. 85.7 % agreed that preoperative discussion with a healthcare professional about the stoma’s location and care would have been beneficial, even if they ultimately chose another treatment option. About 5% of interviewees felt that they had already received enough information from their physicians.

The training module of the ETEI: Skill Learning

The majority of participants believed that they also would have benefitted from preoperative skills-based education. 71.4% agreed that an opportunity to wear a stoma bag for 24 to 48 hours prior to surgery would have allowed them to preemptively experience stoma-related care issues, while 23.8% felt that this might have raised their anxiety levels. 14% of patients agreed that practicing stoma care skills before surgery (e.g., how to use catheters and stoma appliances) would have effectively prepared them for life after surgery. However, an equal proportion of the study population (14%) also indicated preference for post-surgical training on the stoma care skills, rather than pre-surgical training, largely because the emotional stress of cancer diagnosis and treatment consideration might have affected their ability to understand complicated self-care information at the time.

Spousal Information provided by the ETEI

Most participants (90.5%) recommended that their spouses receive the same educational materials, especially since many of them indicated relying upon their spouses and partners for post-operative health care and support. Participants who cared for themselves post-operatively felt that their spouses would have voluntarily searched for information on their own had they wanted to learn, or otherwise did not recommend the intervention materials for their partners.

Timing of the ETEI

76.2 % preferred to have received an educational intervention immediately upon their diagnosis to help them prepare for the surgery's challenges and postoperative period. About 1About 19 % of the study participants, however, preferred to have received the training module following surgery; they believed that they would have been too emotionally occupied and overwhelmed before hand to be able to properly learn the needed self-care skills (e.g., changing of stomal appliances and catheters use). Those who agreed that spouses should have received similar educational materials believed that a pre-surgical intervention would have been helpful. However, 19.1% preferred a post- surgical training intervention, as a pre-surgical training intervention might also raise partners’ anxiety and distress.

Discussion

There is a crucial need for educational and training interventions to enhance MIBC patients’ treatment decisionmaking and preparation for self-care after surgery. with Qualitative evaluation of participants' reports provides evidence of such interventions’ necessity.

Overall, the results of this qualitative study confirm the value of pre-surgical educational materials for MIBC patients and their informal caregivers. Nearly all interviewees expressed belief that they would have made more informed and confident decisions after receiving detailed information, both literary and visual, about each surgical intervention's process, risks, and effects on lifestyle. Those who believed they would have benefitted also believed that their spouses or intimate partners would have as well, given their important caretaking roles.

All participants agreed that receiving the ETEI proposed information about the types of UD procedures, and their side effects would have been helpful prior to surgery. Similarly, the vast majority of patients liked the idea of receiving a prescribed list of questions to ask during their surgical consultation with the physician. Visual information depicting different bladder replacement treatments, stoma appliances, and catheters are perceived as helpful according to more than four-fifths of patients interviewed. Likewise, more than four-fifths of patients believed they would have benefitted from talking to a nurse regarding stoma care, location, and appliances, regardless of treatment preferences.

Patients with MIBC report significant unmet informational and supportive care needs, yet very few resources are currently available to meet them [34, 36, 63, 64]. Thus, knowledge of both MIBC treatment options and their consequences is not only empowering the patient, but also fundamental to an individual's decision-making regarding any issue. Our prior studies of MIBC patients have also shown that they need information regarding each operation's likelihood of effectiveness, risks, benefits, and side effects (both short and long term). Additional knowledge of the self-care skills associated with each treatment choice further facilitates treatment-related decision-making and helps patients prepare for the unknown [34, 36]. Educational tools (e.g., print or Web-based) can provide a vast amount of information [65,66]. However, the readability of the language typically exceeds the national average reading ability [67]. Hence, mere information of any kind or level of complexity does not necessary influence the decision-making process. Patients also benefit from integrating treatment option information with their own personal values and preferences. When an educational intervention or patient- clinician discussion regarding treatment options is coupled with clarification of personally relevant values, the exchange of information is much more productive for both the patient and provider alike [68,69]. According to the US Preventive Services Task Force, a comprehensive decisional tool should:

a. Provide adequate information about the risks, benefits, and limitations of the procedure;

b. Enhance the patient's ability to participate in decisionmaking with providers at a personally desired level; and

c. Help the patient make a decision that is consistent with his/her personal preferences and values [70].

In line with published data, our studies exploring treatment decision-making in cancer patients showed that patient factors including age, race, values, and preferences are significantly influential and should be addressed during decision-making processes [34,36,71]. Promoting insight and prioritizing personal factors along with medical factors are required in preparation of patients for treatment decisions. By considering these factors, providers can assist patients in making informed choices and prepare for the post-treatment self-care requirements.

Anxiety is a normal and well-documented emotional and physiological response to anticipating and awaiting major surgery [72]. While many patients who receive information about their treatment prior to surgery experience relief, others' anxiety may worsen. Our qualitative data also showed that while a large (71.4%) percentage of patients believed that wearing a stoma bag for 24 to 48 hours would have prepared them for this particular operation's post-surgical experience, close to one- third of patients felt that this might have raised their anxiety levels. However, when asked about the best time for patients to learn about the skills needed for self-care, an equal number of patients expressed preferences for a pre-surgical, rather than post-surgical, hands-on training. Patients' preference for post-surgical training involved anticipated lower stress levels after surgery. Not only would reduced stress allow for easier learning, these patients believed that newly emerging, post- surgical coping and adaptation processes would have enabled better understanding of complicated self-care information. It is therefore very important to customize educational intervention and provide resources based on patients' needs and preferences. Studies conducted among other cancer populations (e.g. prostate cancer) have shown that customizing educational tools reduces decisional uncertainty and enhances patients’ understanding of their own values [73].

As our study also suggests, most patients would prefer that their informal caregivers (e.g., partners and spouses) receive the same information and training, particularly before surgery. Our prior qualitative research of MIBC patients showed that many rely on family assistance with self-care [36]. However, most of these family caregivers do not receive formal training for stoma care or catheter use; rather, they learn by trial and error or via internet-based resources. Family caregivers need training in post-operative care both before discharge from the hospital and during the weeks after surgery. The ETEI is meant to a) Provide patients and informal caregivers hands-on post-surgical care training (e.g., for use of catheters and stomal appliances), b) Empower patients to recognize troubling, red flag symptoms such as fever, stoma discoloration, and urinary blockage, c) Further inform patients of when to call the medical team to avoid emergency room visits, andd) Instruct patients on when to pursue follow-up cancer screening tests. The training module of the ETEI provides detailed information about these issues for MIBC patients. Such materials can benefit both the patient and the family care-givers at multiple levels (e.g., preparation for surgery, improving self-care skills, and providing online resources for patient and caregiver support).

Study Limitations

First, study participants were MIBC survivors with close to 50% of participants receiving treatment >1 year before the personal interviews. Including newly diagnosed patients who did not receive treatment yet could provide more timely information about perceived usefulness of the intervention and avoid recall bias. Second, our study participants were recruited from ISMMS and via BCAN website. Majority of participants in our study were Caucasians in relationships (partners/spouses). Thus, our sample might not reflect the general characteristics of the study population. Third, although the study participants suggested that the content of the ETEI is appropriate for both the patient and the informal care-giver, we did not access the caregiver's perspective or input on the ETEI content. Examining the care-giver’s evaluation of the ETEI might reveal other issues and challenges relevant to the care-givers (e.g., care-giving burden, sexuality needs, and social support provision). Additional studies are needed to further explore and confirm the unmet needs of MIBC patients’ informal care-givers to explore their unmet needs and to confirm the appropriateness of the ETEI for the caregivers.

Conclusion

In summary, the study results emphasize the importance of the proposed ETEI and appropriateness of the content of the informational and training modules for both patients and their informal care-givers. The next step of our research (ongoing study) is to examine the feasibility and efficacy of implementing the ETEI in traditional clinic setting to enhance both treatment decisions and skills needed for post-surgical care in both patients and their care-givers. Such study will guide further improvement of the content, delivery method, and evaluation of the ETEI (i.e., in person session versus Web-based interventions).

Practice Implications

Educational and training information in the form of adequate counseling, information booklets and pictorials regarding treatment options, and training for self-care would enable patients to make informed decisions. This could potentially mean an increased need for resources - educational booklets, audio-visuals, trained health care personnel, length ± number of appointments.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by mentored research scholar grants from the American Cancer Society (121193-MRSG-11-103-01- CPPB) and the National Cancer Institute (1R03CA165768-01A1)

References

- NCI (2013) Cancer Stat Facts: Bladder Cancer. National Cancer Institure, India.

- Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Negri E, La Vecchia C, et al. (2011) Trends in mortality from urologic cancers in Europe, 1970-2008. Euro Urol 60(1): 1-15.

- Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, Eheman C, Zauber AG, et al. (2010) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer in u.s, 1975- 2014,. featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates(Cancer) 2010:116:544-73.

- Ferlay J, Randi G, Bosetti C, Levi F, Negri E, et al.(2008) Declining mortality from bladder cancer in Europe.2008 BJUI 101(1):11-9.

- Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni Jr JF,(2006) Cancer epidemiology and prevention: Oxford University Press.2006.

- Burger M, Catto JW, Dalbagni G, Grossman HB, Herr H, et al.(2013) Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder Europe. Euro Urol 2013:63(2):234-41.

- Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, Kaasinen E, Bohle A, et al.(2017) EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladde in Europer. the 2011 update. Euro urol 2017:71(3):447-461.

- Stenzl A, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Kuczyk MA, Merseburger AS, et al.(2011) Treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer in Europe: update of the EAU guidelines. Euro urol 2011:59(6):1009- 18.

- (2002) Clark PE. Urinary diversion after radical cystectomy. Curr treat options oncol. 2002:3(5):389-402.

- Hardt J, Filipas D, Hohenfellner R, (2000)Egle UT. Quality of life in patients with bladder carcinoma after cystectomy. first results of a prospective study. QualLife Res 2000:9(1):1-12.

- Krupski T, (2001) Theodorescu D. Orthotopic neobladder following cystectomy. indications, management, and outcomes. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs.. 2001:28(1):37-46.

- Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, Groshen S, Feng A-C, et al. (2001) Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer. long-term results in 1,054 patients. J clin oncol 2001:19(3):666-75.

- Studer U, Danuser H, Hochreiter W, Springer J, Turner W. (1996) Zingg E. Summary of 10 years' experience with an ileal low-pressure bladder substitute combined with an afferent tubular isoperistaltic segment. World J Urol 1996:14(1):29-39.

- Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, Speights V, Vogelzang NJ, et al. (2003) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer in England. New Engl J Med2003:349(9):859-66.

- Turner WH. (1997) Studer UE. Cystectomy and urinary diversion. Semin surg oncol.1997;13(5): 350-8.

- Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW. (2011) Enhanced Campbell-Walsh Urology: Expert Consult Premium Edition Online Features and Print, 4-Volume Set: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011.

- Konety BR, Allareddy V, Herr H.(2006) Complications after radical cystectomy: analysis of population-based data. Urology. 2006;68(1):58-64.

- Kim SP, Boorjian SA, Shah ND, Karnes RJ, Weight CJ, et al. (2012) Contemporary trends of in hospital complications and mortality for radical cystectomy. BJU int. 2012:110(8):1163-8.

- Albisinni S, Rassweiler J, Abbou CC, Cathelineau X, Chlosta P, et al.(2015) Long term analysis of oncological outcomes after laparoscopic radical cystectomy in Europe: results from a multicentre study by the European Association of Urology (EAU) section of Uro technology. BJU int. 2015;115(6):937-45.

- Dybowski B, Ossolinski K, Ossolinska A, Peller M, Bres-Niewada E,et al.(2015) Impact of stage and comorbidities on five-year survival after radical cystectomy in Poland: single centre experience. Cent European J Urol. 2015;68(3):278-83.

- Hautmann RE, Hautmann SH, Hautmann O.92011) Complications associated with urinary diversion. Nat Rev Urolo. 2011;8(1):667-77.

- Hemelrijck M, Thorstenson A, Smith P, Adolfsson J, Akre O.(2013) Risk of in hospital complications after radical cystectomy for urinary bladder carcinoma: population based follow up study of 7608 patients. BJU int.2013;112(8):1113-20.

- Kim SP, Shah ND, Karnes RJ, Weight CJ, Frank I, et al.(2012) The implications of hospital acquired adverse events on mortality, length of stay and costs for patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. The J urol. 2012;187(6):2011-7.

- Lawrentschuk N, Colombo R, Hakenberg OW, Lerner SP, Mansson W, et al.(2010) Prevention and management of complications following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Eur urol. 2010;57(6):983-1001.

- Masago T, Morizane S, Honda M, Isoyama T, Koumi T, et al. (2015) Estimation of mortality and morbidity risk of radical cystectomy using POSSUM and the Portsmouth predictor equation. Cent European J Urol. 2015;68(3):270-276.

- Niegisch G, Albers P, Rabenalt R. (2014) Perioperative complications and oncological safety of robot-assisted (RARC) vs. open radical cystectomy (ORC). Urol Oncol: 2014:37(2) :966-74.

- Aghazadeh MA, Barocas DA, Salem S, Clark PE, Cookson MS, et al. (2011) Determining factors for hospital discharge status after radical cystectomy in a large contemporary cohort. J urol. 2011;185(1):85-9.

- Krajewski W, Piszczek R, Krajewska M, Dembowski J, Zdrojowy R.(2013) Urinary diversion metabolic complications-underestimated problem. official organ Wroclaw Medical University. Adv clin exp med: 2013;23(4):633-8.

- Fulham J.(2008) Providing dietary advice for the individual with a stoma. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(2):s22-7.

- Link RE, Lerner SP.(2001) Rebuilding the lower urinary tract after cystectomy: a roadmap for patient selection and counseling. Semin urol oncol.2001; 19(1): 24-36.

- Matulewicz RS, Brennan J, Pruthi RS, Kundu SD, Gonzalez CM,et al.(2015) Radical cystectomy perioperative care redesign. Urology. 2015;86(6):1076-86.

- Smith J, Pruthi RS, McGrath J.(2014) Enhanced recovery programmes for patients undergoing radical cystectomy. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(8):437-44.

- Asgari M, Safarinejad M, Shakhssalim N, Soleimani M, Shahabi A,et al. (2013) Sexual function after non-nerve-sparing radical cystoprostatectomy: a comparison between ileal conduit urinary diversion and orthotopic ileal neobladder substitution. Int braz j urol. 2013;39(4):474-83.

- Mohamed NE, Pisipati S, Lee CT, Goltz HH, Latini DM,et al.(2016) Unmet informational and supportive care needs of patients following cystectomy for bladder cancer based on age, sex, and treatment choices Seminars and Original Investigations: Elsevier. Urol Oncol. 2016; 34(12): 531. e7-. e14.

- Shariat SF, Sfakianos JP, Droller MJ, Karakiewicz PI, Meryn S,et al.(2010) The effect of age and gender on bladder cancer: a critical review of the literature. BJU int. 2010;105(3):300-8.

- Mohamed NE, Herrera PC, Hudson S, Revenson TA, Lee CT, et al.(2014) Muscle invasive bladder cancer: examining survivor burden and unmet needs.J urol. 2014;191(1):48-53.

- Madersbacher S, Schmidt J, Eberle JM, Thoeny HC, Burkhard F, et al. (2003) Long-term outcome of ileal conduit diversion. J urol. 2003;169(3):985-90.

- Neal DE. (1985) Complications of ileal conduit diversion in adults with cancer followed up for at least five years. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290(6483):1695-7.

- Nieuwenhuijzen JA, de Vries RR, Bex A, van der Poel HG, Meinhardt W, Antonini N, et al.(2008) Urinary diversions after cystectomy: the association of clinical factors, complications and functional results of four different diversions. Euro urol. 2008;53(4):834-44.

- Wood D, Allen S, Hussain M, Greenwell T, Shah P.(2004) Stomal complications of ileal conduits are significantly higher when formed in women with intractable urinary incontinence. J urol. 2004;172(6 pt1):2300-3.

- Hautmann RE, Volkmer BG, Schumacher MC, Gschwend JE, Studer UE. Long-term results of standard procedures in urology: the ileal neobladder. World journal of urology. 2006;24:305-14.

- Stein J, Skinner D. Results with radical cystectomy for treating bladder cancer: a 'reference standard'for high grade, invasive bladder cancer. BJU international. 2003;92:12-7.

- Monn MF, Kaimakliotis HZ, Cary KC, Pedrosa JA, Flack CK, Koch MO, et al. Short-term morbidity and mortality of Indiana pouch, ileal conduit, and neobladder urinary diversion following radical cystectomy. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations: Elsevier; 2014. p. 1151-7.

- Park J, Ahn H. Radical cystectomy and orthotopic bladder substitution using ileum. Korean journal of urology. 2011;52:233-40.

- Kim SP, Shah ND, Weight CJ, Thompson RH, Wang JK, Karnes RJ, et al. Population based trends in urinary diversion among patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. BJU international. 2013;112:478-84.

- Crawford E, Skinner D. Salvage cystectomy after irradiation failure. The Journal of urology. 1980;123:32-4.

- Crozier J, Hennessey D, Sengupta S, Bolton D, Lawrentschuk N. A systematic review of ileal conduit and neobladder outcomes in primary bladder cancer. Urology. 2016;96:74-9.

- Smith Jr J, Whitmore Jr W. Salvage cystectomy for bladder cancer after failure of definitive irradiation. The Journal of urology. 1981;125:643-5.

- Swanson DA, von Eschenbach AC, Bracken RB, Johnson DE. Salvage cystectomy for bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;47:2275-9.

- Afak YS, Wazir B, Hamid A, Wani M, Aziz R. Comparative study of various forms of urinary diversion after radical cystectomy in muscle invasive carcinoma urinary bladder. International journal of health sciences. 2009;3:3.

- Ashley MS, Daneshmand S. Factors influencing the choice of urinary diversion in patients undergoing radical cystectomy. BJU international. 2010;106:654-7.

- Lee CT, Mei M, Ashley J, Breslow G, O'Donnell M, Gilbert S, et al. Patient resources available to bladder cancer patients: a pilot study of healthcare providers. Urology. 2012;79:172-7.

- Mohamed N, Diefenbach M, Goltz H, Lee C, Latini D, Kowalkowski M, et al. Muscle invasive bladder cancer: from diagnosis to survivorship. Advances in urology. 2012;2012.

- Mohamed NE, Bovbjerg DH, Montgomery GH, Hall SJ, Diefenbach MA. Pretreatment depressive symptoms and treatment modality predict post-treatment disease-specific quality of life among patients with localized prostate cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations: Elsevier; 2012. p. 804-12.

- Mohamed NE, Chaoprang Herrera P, Hall S, Diefenbach MA. An Educational Intervention for Patients with Invasive Bladder Cancer. Society of Behavioral Medicine. San Francisco2013.

- https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/odsf.Pdf.

- https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/ODSF-workshop/ODSF-Workshop- Summary.pdf.

- Legare F, O'Connor AM, Graham ID, Wells GA, Tremblay S. Impact of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework on the agreement and the difference between patients' and physicians' decisional conflict. Medical Decision Making. 2006;26:373-90.

- Krueger J, Rothbart M. Contrast and accentuation effects in category learning. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1990;59:651.

- Rabiee F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the nutrition society. 2004;63:655-60.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990.

- ATLAS.ti. The Knowledge Workbench. Berlin.

- Janoff-Bulman R. Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: Applications of the schema construct. Social cognition. 1989;7:113-36.

- Prout GR, Wesley MN, Yancik R, Ries LA, Havlik RJ, Edwards BK. Age and comorbidity impact surgical therapy in older bladder carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2005;104:1638-47.

- Smits R, Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R, Tzelepis F, Henskens F, Paul C, et al. Tailored and integrated Web-based tools for improving psychosocial outcomes of cancer patients: The DoTTI development framework. Journal of medical Internet research. 2014;16:e76.

- Webb T, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of medical Internet research. 2010;12:e4.

- Fagerlin A, Rovner D, Stableford S, Jentoft C, Wei JT, Holmes-Rovner M. Patient education materials about the treatment of early-stage prostate cancer: a critical review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140:721-8.

- Institute OHR. Ottawa decision support framework: Update, gaps and research priorities.

- O'Connor A, Jacobsen M. Decisional conflict: Supporting people experiencing uncertainty about options affecting their health. Ottowa, Canada: Patient Decision Aid Research Group http://homeless ehclients com/images/uploads/W-2_Ottawa_Decision_Making_ tool- -_Reading-1 pdf Retrieved March. 2007;6:2012.

- Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH, Force SD-MWotUPST. Shared decision making about screening and chemoprevention: a suggested approach from the US Preventive Services Task Force. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004;26:56-66.

- Berry DL, Ellis WJ, Woods NF, Schwien C, Mullen KH, Yang C. Treatment decision-making by men with localized prostate cancer: the influence of personal factors. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations: Elsevier; 2003. p. 93-100.

- http://www.surgeryencyclopedia.com/Pa-St/Preoperative-Care.html.

- Berry DL, Halpenny B, Hong F, Wolpin S, Lober WB, Russell KJ, et al. The Personal Patient Profile-Prostate decision support for men with localized prostate cancer: a multi-center randomized trial. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations: Elsevier; 2013. p. 1012-21.