Seroepidemiologic Study of Subclinical Leishmaniasis in Uremic Patients on Hemodialysis in Lebanon

Nuwayri Salti N1*, Daouk Majida2 and Khouzama Knio3

1Department of Human Morphology, American University of Beirut, Lebanon

2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Beirut, Lebanon

3Department of Biology, American University of Beirut, Lebanon

Submission: August 06, 2017; Published: September 14, 2017

*Corresponding author: Nuha Nuwayri Salti, Department of Human Morphology, American University of Beirut, Lebanon Tel: 9615456862; Email: nuhaakanoueiri@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Nuwayri S, Daouk M, Khouzama K. Seroepidemiologic Study of Subclinical Leishmaniasis in Uremic Patients on Hemodialysis in Lebanon. JOJ uro & nephron. 2017; 4(1): 555629. DOI: 10.19080/JOJUN.2017.04.555629

Abstract

Lebanon is in the center of a region that is hyper-endemic for leishmaniases, yet the observed prevalence of the cutaneous form (cL) has been rather low in this country. What is important is that in about one third of these patients, with cutaneous lesions, we isolated the parasites from the blood stream. In all studied samples (skin or blood) the parasite was found to be L. donovanisenso lato. Besides, the symptoms, in subjects with infected blood, are often vague and non-specific, and remain so, even after the skin sores have healed, while the parasite is still present in blood. This led us to realize, that the prevalence of subjects with infected blood, by this strain of parasite, may be much greater than we ever suspected, and even more likely in subjects with poor body defenses, such as in patients with chronic renal failure and uremia. The current study is to explore this possibility looking for the presence of parasites in patients with depressed immunity secondary to chronic renal failure. We hope that once this invasion, if present, is uncovered and treated, will rid the immune system of this overload, improving thus its performance leading to a better quality of life.

Introduction

The epidemiology of leishmaniasis in Lebanon seems to be distinctly different from the situation in neighboring Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine and Israel [1-5]. In Lebanon it is sporadic with a low prevalence, 0.18% in the rural, 0.41% in the urban areas [6], in contrast to the higher prevalence in neighboring countries, in which it reaches sometimes, hyper-endemic levels as is the case in Syria [7,8]. Several publications revealed that the infective agent in Lebanon is neither L. tropica nor L. major but of the L. donovani group [9-11]. Furthermore, the parasites causing the skin lesions, sometimes spread to invade the blood stream [12,13].

In addition, and in several similar foci, patients with AIDS were found co-infected by this parasite [14,15]. On the other hand L. tropica, caused kala azar in subjects coming from non-endemic regions totally naïve to these parasites, such as happened to some subjects, visiting endemic regions such as foreigners during “Desert Storm” [16,17]. Finally, realizing the high prevalence of infection in the reservoir animal for L. donnovani, (stray dogs) [6] were alized that we may be missing a significant number of undiagnosed patients with either a modified clinical picture, or that silent carriers are more frequent than suspected, hence we are witnessing the tip of the iceberg.

We started testing this hypothesis by investigating subjects who could be an easy target to this parasite, a group of immune-suppressed patients with uremia and on hemodialysis. The patients belonged to two different environments: the first is a typically and strictly rural environment and the second a totally open urban environment. We conducted a serologic study evaluating the level of antibodies to this parasite in the sera of the patients and controls. Elevated antibodies often indicate concurrent infection [18,19]. When detected such subjects, if treated, the burden on their immune system becomes lighter, which must improve their defenses, hoping that this leads to better quality life.

Materials and Methods

The study subjects were composed of two major populations with the appropriate controls. The first population (group I) were uremic patients (U). They were selected at the dialysis unit at Ayn and Zayn hospital (UAZH). This hospital is situated in a totally rural community, being the only medical center serving the local population.). We chose 82 patients aged between 30 and 60 years. They had been on dialysis for more than one year. They were a majority of males with only 38 females. We made sure that they had neither other serious disease nor any detectable complication. They all came from similar socioeconomic backgrounds, had the same type of food, and activities.

They were living in the same style houses, and were exposed to the same fauna and flora. They belonged to a small selfsufficient community which had all the necessary substrata that allowed it, to lead a totally normal life without any need to visit larger towns and especially the capital Beirut. The normal controls were picked up from the same environment as the patient. They were normal subjects, some even related to the patients, and of the same gender and as close in age as possible). In contrast, Group II, were selected from a larger number of patients on hem dialysis at the Dialysis Unit at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC). We tried to select patients, close in age and socio-economic status to the group from (UAZH), except that they belonged to the capital for many generations.

This was simple because the pool at AUBMC is quite large. We followed, in the choice of patients, the same criteria as for choosing patients at AZ. The same was respected in the choice of controls (from the same background as the patients). Using micro-ELIZA [18,19] we evaluated anti-Leishmania antibodies in the serum of every subject [18,19]. The control subjects were treated exactly the same way. For antigens used were whole lysate of a reference strain of L. donovani in addition to rK39 a recombinant copy of Leishmania chagasi natural antigen shown to specifically detect antibodies to members of the L. donovani (L. chagasi, L. infantum) complex. rk39 was obtained from CORIXA Corp (courtesy late Dr. Yasser Skeiky CORIXA CORP Seattle Washington State, USA) [20]. We tested 50 samples for each of our control groups and 82 (AZHU), 35 (AUBMC). In each plate well known positive and negative control sera were included. All sera were used at I/100dilution. All tests were run in duplicate repeated at least twice, and sometime in more than one laboratory (ours and CORIXA laboratories). For each test plate the cutoff point was calculated from the mean of negative control sera readings +3 standard deviation from the mean.

Results and Discussion

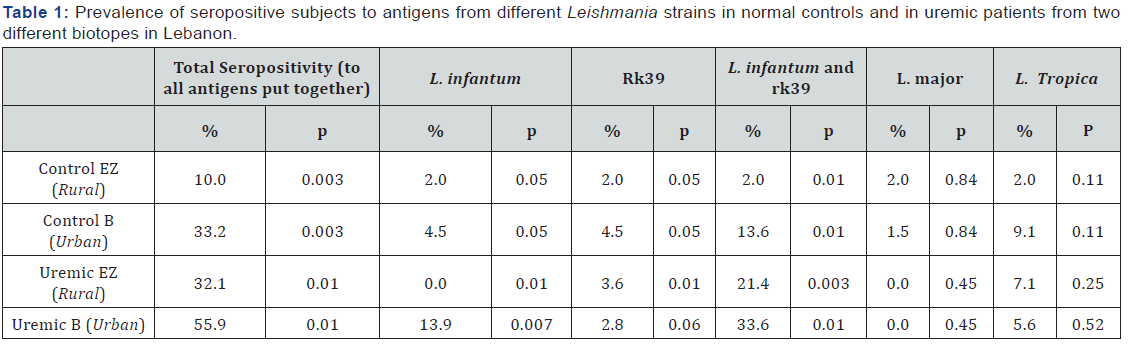

The obtained results proved that an important proportion of uremic patients, in Lebanon, have elevated levels of antibodies to Leishmania antigens. Whether this is a sign of infection prior post the uremic state is not known. Whether the patient is still carrying live parasites has not been determined, especially that, smears of peripheral blood rarely show enough monocytes to detect a low grade infection, besides in many patients and or carriers, even when parasites are detected by microscopy they failed to grow in cultures for classification by iso-enzyme electrophoresis. Other tests such as detecting portions of parasite DNA in some patients is not indicative of the presence of entire live or active parasites. While leishmaniasis is known to be hypo-endemic in Lebanon, yet control subjects, with a negative history, had high levels of antibodies in their sera, and the titer was higher when Leishmania antigens from different parasite strains were combined in the same well (36% in AZC versus 69% in AUBC), a finding totally unsuspected. A similar proportion was found in the uremic patients although the values reached in serum were higher (62% AZHUvs 77% in AUBMC). L. infantum is evidently the principle strain of parasite infecting and causing a response in both the control and in about 25% of the immune suppressed populations. But this proportion becomes greater when the lysate of L. donovani is combined with K39 (extract from L. chagasi). The difference in the level of antibodies in patients versus controls from either locale seems to be the same. A second unexpected finding is the appreciably important response to L. tropica which, in our region and population, causes cutaneous leishmaniasis. None of these patients reported any skin lesion at any time before or after renal failure, yet anti - L. tropica antibodies in serum, are significantly higher in patients from rural than those living in the urban environment (AZH vs AUBH).

Finally, as expected, from many of our studies in this field, L. major seems not to exist in Lebanon (not in control subjects nor in uremic patients). This may be the result of the absence of the appropriate reservoir animals in our fona (Ashford R. personal communication, upon his visit to Lebanon). To close, one remarkable fact, that should not be overlooked, in that this group of patients carrying high levels of anti-Leishmania antibodies, consist of a population of immune suppressed patients. The higher prevalence of high antibody levels in the uremic patients over the controls proves that a proportion of these patients on dialysis probably acquired the infection after renal Failure. They are likely to carry live parasites, and this makes treatment necessary and most probably beneficial. The same proportion of infected patients exists in both groups (Table 1). All the studies conducted on the prevalence and incidence of leishmaniasis in Lebanon agree, that this infection, is hypo-endemic. The present data reveals that in these already immune-suppressed uremic subjects the clinical expression of Kala azar is probably far from the expected, therefore testing for this and other similar parasites is highly recommended in endemic regions, such as the Mediterranean Basin. Another interesting finding is the fact that L. tropica that has been established to be hyper-endemic in our area causing coetaneous infections for centuries, seems to have become more aggressive in such immunosuppressed patients. This fact should be further investigated, especially in immunosuppressed cases, for other reasons, such as autoimmune disorders. Finally this data reconfirms, our previous affirmation that L. major does not exist in Lebanon especially that the reservoir animal is apparently totally absent in our environment. To end with the increasing number of Leishmanianaïve subjects staying for prolonged periods in our part of the world, we should be aware that even dermotropic strains of this parasite may become particularly invasive and cause Kala-azar, with a symptomatology either typical of systemic disease or probably with a modified presentation.

Conclusion

To conclude, with the modern developments in medical care there is a population of patients, who survives much longer than before, especially those with chronic disorders. Such patients, with depleted immunity, wherever they exist are prone to a large variety of opportunistic infectious agents. The real danger is when the organism remains cryptic, while it erodes an already burdened immune system. This may be the reason for the very poor performance of some of our patients on dialysis, especially those living around the Mediterranean Basin. Finally we should always try to optimize care to our patients on dialysis or to those immune compromised, looking for any subclinical infection which adds to the load upon unaware patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Samia Mroueh and Miss Fatmeh Jaafar for their technical help. We also thank Miss. Samira Khoury for reviewing the manuscript professor at the Civilization Sequence Program, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, American University of Beirut. Ethics approval and consent to participate. Every subject filled up a consent form to participate in this study, and to allow our team to publish all the information collected thus, provided the identity of the participant is not disclosed.

References

- Adler S, Katzenellenbogen I (1952) The problem of the association between particular strains of Leishmania tropica and the clinical manifestations produced by them. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 46: 25-32.

- Adler S (1964) Leishmania. In: Adv Parasitol Dawes [Eds.], London and New York Academic Press, USA pp. 35-96.

- Hommel M (1978) The genus leishmania: Biology of the parasites-clinical aspects. Bull Inst Pasteur 76: 5.

- Lainson R (1982) Leishmaniasis. Handbook Series in Zoonoses 2:41- 103.

- Desjeux P (1991) Information on the Epidemiology and control of the Leishmaniasis by country or territory. Geneva: World Health Organization 930: 16, 18, 29.

- Nuwayri-Salti N, Baydoun E, El-Tawk R, Makki FR, Knio k (2000) The epidemiology of leishmaniases in Lebanon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 94(2): 164-166.

- Ashford W, Rioux JA, Jalouk L, Khiami A, Dye C (1993) Evidence for a long term increase in the incidence of Leishmania tropica in Aleppo, Syria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 87(3): 247-249.

- Tayeh A, Jalouk L, Cairncross S (1997) Twenty years of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Aleppo, Syria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 91(6): 657-659.

- Rioux JA, Lanotte G, Maazoun R, Rerello R, Pratlong F, et al. (1980) Leishmania infantum, the strain of the autochthonous oriental sore. Apropos of the biochemical identification of 2 strains isolated in the eastern Pyrenees. CR Seances Acad Sci D 291(8): 701-3.2.

- Postigo JA (2010) Leishmaniasis in the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region. Int J Antimicrob Agents 36 (Suppl 1): S62–S62.

- del Giudice P, Marty P, Lacour JP, Perrin C, Pratlong F, et al. (1998) Cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum. Case reports and literature review. Arch Dermatol 134(2): 193-8.

- Nuwayri-Salti N, Salman S, Shahin NM, Malak J (1999) Leishmania donovani invasion of the blood in a child with dermal leishmaniasis. Ann Trop Paediatr 19(1): 61-64.

- Nakkash-Chmaisse H, Makki R, Knio K, Nahhas G, Nuwayri-Salti N (2011) Detection of Leishmania parasites in the blood of patients with isolated cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Infect Dis 15(7): e491-e494.

- Dereure J, Pratlong F, Reynes J, Basset D, Bastien P, et al. (1998) Haemoculture as a tool for diagnosing visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients: interest for parasite identification. Bull World Health Organ 76(2): 203-206.

- Agostoni C, Dorigoni N, Malfitano A, Caggese L, Marchetti G, et al. (1998) Mediterranean leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients:epidemiological, clinical, and diagnostic features of 22 cases. Infection 26(2): 93-99.

- Grogl M, Daugrida JL, Hoover DL, Magill AJ, Berman JD (1993) Survivability and infectivity of viscerotropic Leishmaniatropica from Operation desert Storm participants in human blood products maintained under blood bank conditions. Am J Trop Med Hyg 49(3): 308-315.

- Magill AJ, Grogl M, Gasser RA, Sun W, Oster CN (1993) Visceral infection caused by Leishmania tropica in veterans of operation Desert Storm. New England Journal of Medicine 328(19): 1383-1387.

- Jahn A, Lelmett JM, Diesfeld HJ (1986) Sero epidemiological study on kala-azar in Baringo district, Kenya J Trop Med Hyg 89(2): 91-104.

- Choudhry A, Guru PY, Saxena RP, Tandon A, Saxena KC (1990) Enzymelinked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of kala-azar in Bhadohi (varanasi), India. Transf R Soc Trop Med and Hyg 84(3): 363-366.

- Zijlstra EE, Daifalla NS, Kager PA, EAG K, El-Hassan AM (1998) rK39 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of Leishmania donovani infection.Clin Diagn lab immunol 5 (5): 717-720.