New Criterion for Ankle-Brachial Index Supposed to Predict Cardiovascular Complication and Its Correlation to Chronic Kidney Disease in Children

Rosmayanti Syafriani Siregar*, Dany Hilmanto, Oke Rina Ramayani

1Department of Pediatrics, Sumatera Utara University, Indonesia

2Department of Pediatrics, Padjajaran University, Indonesia

Submission: July 01, 2017; Published: July 20, 2017

*Corresponding author: Rosmayanti Syafriani Siregar, Pediatrics Department, Sumatera Utara University, Hadam Malik Hospital, Medan, Indonesia, Email: oke_rina@yahoo.com

How to cite this article: Rosmayanti Syafriani S, Dany H, Oke Rina R. New Criterion for Ankle-Brachial Index Supposed to Predict Cardiovascular 002 Complication and Its Correlation to Chronic Kidney Disease in Children. JOJ uro & nephron. 2017; 3(5): 555621. DOI: 10.19080/JOJUN.2017.03.555621

Abstract

Background: Screening for peripheral arterial disease (PAD) using ankle brachial index (ABI) is important because of there is no optimal testing strategy for subclinical atherosclerosis in relation to cardiovascular events pediatric CKD. Despite knowledge about standard criterion on ABI based on angiography, carotid intimae medial thickness (CIMT) often used to analysis subclinical atherosclerosis. The purpose of this study is to establish prediction systems for CKD children with ABI assay based on CIMT to identify CKD patients experiencing subclinical atherosclerosis.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was done to identify the correlation ABI to CIMT as landmark of cardiovascular complication. It took place from December 2016 until April 2017 in H. Adam Malik Hospital, Medan, Indonesia. An inclusion criterion was children over 2 years old with CKD. Exclusion criteria were history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity. Staging CKD was divided into mild, moderate and severe based on Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. Measurement of ABI was gained by comparing systolic blood pressure of lower and upper limbs. Measurement of CIMT was done by using longitudinal view of echocardiography.

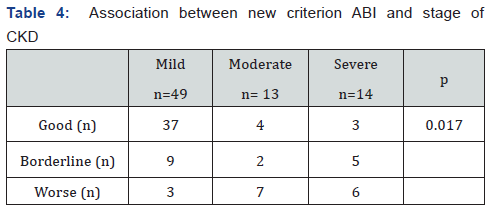

Results: A total of 76 patients CKD involved in study with a mean age of 9.8±4.48 years and the glomerular disease was the common cause. Mean and standard deviation CIMT values for severe stage were higher (0.911±0.29mm) compared of mild and moderate CKD stages (0.749±0.19 and 0.725±0.29mm, respectively). Mean and standard deviation ABI values for severe stage were higher (0.999±0.08) compared of mild and moderate CKD (0.964±0.04 and 0.959±0.09, respectively). After done new criterion for ABI as good, borderline and worse; there was correlation of ABI to stages CKD (p=0.017).

Conclusions: There is significant correlation between new ABI criterion and CKD staging. Borderline and worse ABI criteria are common in moderate and severe CKD.

Keywords: Ankle brachial index; Carotid intimae media thickness; Cardiovascular complication; Chronic kidney diseases

Abbreviations: SPAD: Screening for Peripheral Arterial Disease; ABI: Ankle Brachial Index; CIMT: Carotid Intimae Medial Thickness; KDIGO: Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; PAD: Peripheral Arterial Diseases

Introduction

Children with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have thousand fold risk of death from cardiovascular disease as compared to normal children. Blood pressure is an important determinant of cardiovascular risk and lowering blood pressure reduces cardiovascular events in this population. Longer duration of CKD and the presence of glomerular diseases (versus non- glomerular disease, such as structural abnormalities) had a higher risk for both hypertension and uncontrolled blood pressure. One method to define the abnormality cardiovascular in CKD patient is ankle- brachial index (ABI). The ABI is a ratio of Doppler-recorded systolic blood pressures in the lower and upper extremities. In normally persons, arterial pressures increase with greater distance from the heart, because of increasing impedance with increasing arterial taper, resulting in higher systolic blood pressures at the ankle as compared with the brachial arteries. The persons with ABI <0.90 is associated with a two-to threefold increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. An ABI less than 0.90 is highly sensitive and specific for angiographically diagnosed peripheral arterial diseases (PAD). Several prospective studies have demonstrated the presence of PAD as an independent predictor for cardiovascular and cerebral ischemia events, although no symptoms of PAD such as claudicatio intermittent, ischemic pain at rest, with abnormalities of lower limb pulsation examination is appeared.

Screening for PAD using ABI is important because of there is no optimal testing strategy for atherosclerosis in relation to cardiovascular events pediatric CKD in primary care. A study by Arroyo et al. [1] found that the value of ABI in adult CKD patients was correlated with diabetes, hyperlipidemia, inflammation and mineral bone disease, which is the most common cause of PAD in adults; however this relationship is still debate in pediatric area. In pediatric CKD, symptom of PAD is usually subtle and then cardiovascular complication isn’t very similar like adult patients. Use of easy, inexpensive, and self-administered cardiovascular disease complications is necessary for early detection cardiovascular complication.

To increase the effectiveness of ABI analysis, the identification of targeted patient cohorts is therefore highly needed. However, physicians are arguably inefficient in applying a multitude of available ABI prediction scores for specific conditions and specific patient cohorts. Recent advances in imaging technology such as carotid intima media thickness (CIMT) have identified many early functional and structural vascular changes, some of which may reflect subclinical atherosclerosis, and therefore provide areas of potential interest for diagnostic tests of preclinical atherosclerosis [2,3]. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to establish prediction systems for in-patient and outpatient CKD children with PAD assay with CIMT to identify patients experiencing subclinical atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Pediatric patients were consecutively enrolled from the patients in H.Adam Malik Hospitals Medan, Indonesia between September 2016 to February 2017. Inclusion criteria were child with age upper than 2 years old and diagnosed with CKD. Pediatric patients with a clinical history of cardiac abnormalities, diabetes and obesity were excluded. This study was approved by Ethical Committee Sumatera Utara University, Indonesia. All the patients or parents gave written informed consent.

Definition of CKD

We used Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) definitions for CKD staging. The KDIGO definition was used as an internationally agreed standard of CKD progression that was observed more frequently in our study [4]. Progression of CKD was defined as a 25% decline in GFR, coupled with a worsening of GFR category, or an increase in albuminuria category. We define mild stage based on stages 1 and 2; stage moderate based on stages 3A and 3B; also stage severe based on stages 4 and 5 on KDIGO definitions.

ABI measurement

Measurements for calculation of ABI were obtained using a hand-held Doppler instrument with a 5-mHz probe (Parks Model BT 200) as recommended by current guidelines [5]. Systolic blood pressure measurements were obtained from bilateral brachial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries. Brachial artery pressures were averaged to obtain the ABI denominator. When the two brachial artery pressures differed by 10mmHg or more, the highest brachial artery pressure was used as the denominator. To avoid a potential bias from subclavian stenosis, the higher value was used for the brachial artery pressure. For each lower extremity, the ABI numerator used was the highest pressure (dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial) from that leg. ABI was calculated as the ratio of brachial-to-ankle artery pressure for each leg and the smaller value was recorded. The values of the ABI were measured 10 to 30 minute before dialysis for ESRD patients. The intra-reader and inter-reader co-efficients of variation were 5.3% and 3.5% respectively. The standard criterion for ABI in this study is defined normal (0.9-1.1) and abnormal (<0.9) based on previous literature.

Analysis for carotid intimal media thickness (CIMT) and subclinical atherosclerosis

An ultrasonograph (Aloka 2000) equipped with a 7.5 MHz linear type B-mode probe was used by a pediatric cardiologist specialist to evaluate diameters common carotid arteries. Patients were in the supine position with their neck hyper extended and turned 30-45 degrees contralaterally to the probe. Bilateral carotid arteries were observed obliquely from anterior and posterior directions. The bilateral mid common carotid artery was imaged in transverse and longitudinal planes using a 5- to 12-MHz linear array transducer, and measured for twodimensional diameter at peak systole and end diastole. The intima-media thickness of the bilateral distal common carotid artery was measured along the far wall using the point-to-point method. Three measurements were obtained on each side by a single pediatric cardiologist sonographer, and three values were then averaged, yielding the overall CIMT measurement. Measurements obtained in this manner are reproducible in children, with a coefficient of variation ranging from 8.5% to 10.5%. According to CKID study [6], the median CIMT being greater in CKD group than in the normal controls, the 75th percentile (0.48 versus 0.45), 90th percentile (0.53 versus 0.48) and 95th percentile (0.57 versus 0.51) were also larger in the CKD participants. These significant differences persisted after adjusting for differences in age, sex, and race. These values used to analysis subclinical atherosclerosis. A subject called having subclinical atherosclerosis if values of CIMT are in upper limit of 0.57±2SD based on age and sex.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables of subclinical atherosclerosis were compared by unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney test as appropriate. Categorical variables of subclinical atherosclerosis were compared by chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. To construct categorical variables from continuous data, a cutoff point was obtained by receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. The curves were used to plot true positive (sensitivity) against false positive (1-specificity) rates. The area under the curve (AUC) is an indication of how well a parameter distinguishes a diagnostic state (presence of absence of subclinical atherosclerosis in this case). All of the statistical tests were 2-sided, and the differences were considered statistically significant at a P-value of <0.05.

Results (Figure 2)

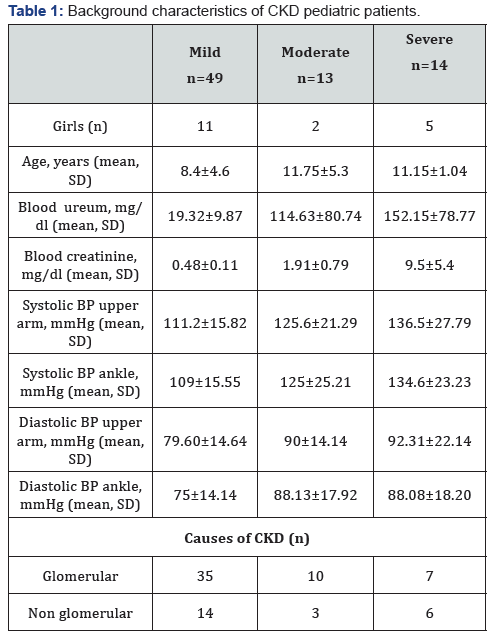

Table 1 showed background characteristic of CKD patients. There were 76 participants with mean age of 9.4±4.48 years for all stages CKD. There were 49 mild CKD, 13 moderate CKD and 14 severe CKD. Mean of systolic or diastolic blood pressure in upper arm and ankle were higher in severe CKD. The glomerular causes of CKD were more frequently than non-glomerular causes of CKD in this study.

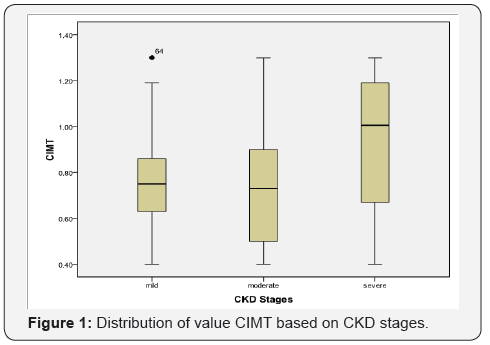

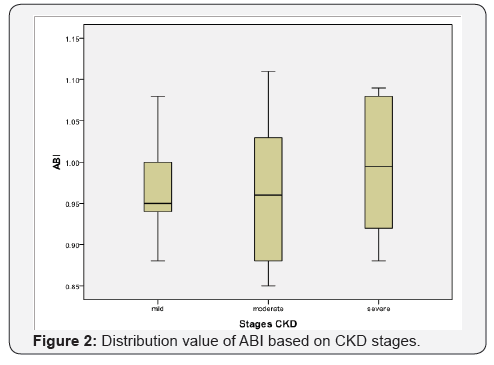

Figure 1 and Figure 2 showed distribution of value CIMT and ABI based on CKD stages. Mean and standard deviation CIMT values for severe stage were higher (0.911±0.29mm) compared of mild and moderate CKD stages (0.749±0.19 and 0.725±0.29mm, respectively). Mean and standard deviation ABI values for severe stage were higher (0.999±0.08) compared of mild and moderate CKD (0.964±0.04 and 0.959±0.09, respectively).

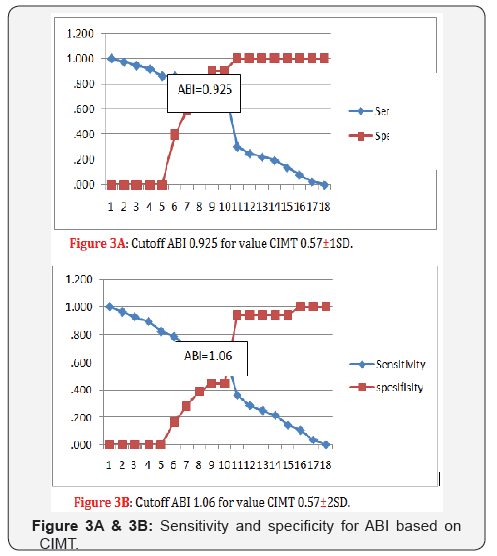

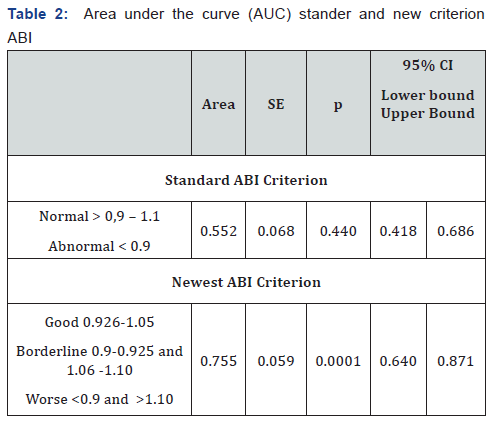

Figure 3a & 3b showed sensitivity and specificity ABI based on CIMT value. CIMT value 0.57±1SD or 0.57±2SD was taken based on CKID study. Value 0.925 and 1.06 for ABI were the value with good sensitivity and specificity for borderline ABI criteria. Figure 4 showed ROC for new criterion ABI and standard ABI. Area under the curve new criterion ABI compared to standard criterion ABI was moderate (0.755 vs 0.552) (Table 2).

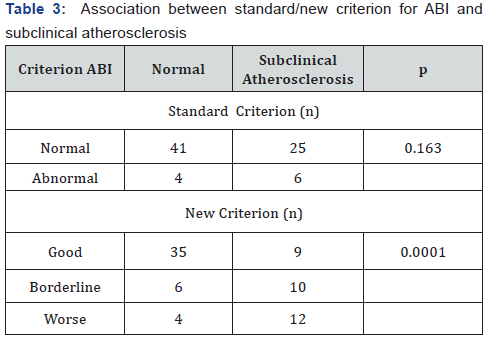

Table 3 showed association between standard and new criterion for ABI and subclinical atherosclerosis. In new criterion for ABI, subject with borderline and worse criteria were more frequent experience subclinical atherosclerosis significantly (p=0001). Subject with borderline and worse criteria for ABI values were also more frequent had stages moderate and severe for CKD (p=0.017), (Table 4).

Discussion

Chronic kidney disease in children is a condition of permanent kidney damage and tends to be progressive to endstage renal failure [7,8]. Epidemiological and CKD registry data in children is very limited, especially in the early stages, because at this stage it is often asymptomatic and often unreported. The results of this study note that the results are not much different from previous studies. From 76 subjects of CKD children who participated in this study, found that patients with mild stage CKD were more common than moderate and severe stages.

The mechanisms that lead to cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD originate primarily with vascular or myocardial injury, and perhaps from uremia itself. In children with CKD, subclinical manifestations of vascular disease have been reported, and subclinical evidence of atherosclerosis with intimal plaque may be present in children with ESRD. Most risk factors for the development of cardiovascular disease are highly prevalent in patients with CKD. Hypertension is present in nearly one half of children with CKD and in more than one half of patients undergoing dialysis. Hypertension is even more common in renal transplant recipients.

It was shown that the ABI is an indicator of atherosclerosis at other vascular sites and can serve as a prognostic marker for cardiovascular events, even in the absence of symptoms of PAD. A factor that affects ABI values is an increase in systolic blood pressure in the lower limb. This is due to changes in blood vessel structure, thickening of the walls with the diameter of the lumen of the blood vessels that tend to persist by the process of atherosclerosis.

Peripheral vascular atherosclerosis manifests as PAD in patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and CKD. It is often found at the symptomatic stage in adult, whereas sub-clinical atherosclerosis is very important for pediatricians to know the prognosis of subsequent cardiovascular complications in pediatric CKD patients [8]. Studies conducted Matsusitha et al. [9] showed that ABI is the most powerful predictor of PAD and is highly recommended as a sub-clinical examination of atherosclerosis. Newman et al. [10] showed that the ABI value <0.9 in healthy adults, had twice the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, meanwhile O’Hare et al. [11] showed that adult CKD had a nine fold risk of developing cardiovascular complications.

The value of ABI’s cutoff as a marker of cardiovascular complications is still debated to date. ABI grouping with only standard criteria, less able to distinguish patients with ‘border line’ risk factors. The ABI collaboration meta-analysis study demonstrated cardiovascular and mortality risk, distributed as an inverted J-letter. The risk of death from cardiovascular complications was highest at ABI <1.11 as well as ABI>1.4. ABI values ranging from 1.11 to 1.4 had the lowest cardiovascular mortality risk. Assessment of ABI with certain cut-off, may exclude the actual subject at risk for cardiovascular events.

In our study, we determined the grouping of new ABI values based on area under the curve (AUC) value. These scores to assess the value ABI based on the diagnostic value of cardiovascular complications (CIMT) in the study subjects. We defined three ABI categories, namely good, border line and worse. Borderline ABI is defined (0.9-0.925) and (1.06-1.10). This ‘border line’ criteria shows that participant with subclinical atherosclerosis could have increased risk of cardiovascular events especially in pediatric CKD. Researchers continue to use the term ‘borderline’, describing caution in determining cardiovascular events based on ABI cut-off values, and may still require further validation in clinical practice.

Mc Dermott et al. [12] showed that in adult patients, borderline ABI values (ABI between 0.9-0.99) were associated with a significantly higher prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis in comparison with normal ABI values (ABI 1.10-1.29). In children especially CKD patients, there is no data about ‘borderline’ ABI values. Our study suggests the new criterion for ABI borderline in children CKD patients based on CIMT values. Examination of CIMT values in children has been used extensively but few study using CIMT as end point. The success of the CIMT measure in the research area has fueled a growing sense that CIMT measures should be adapted for clinical use to either screen or rule out existing disease, target therapeutic strategies, and evaluate therapeutic benefit.

After the ABI grouping into three criteria, this study found correlation between ABI criteria and degree of CKD. Borderline and worse ABI criteria were more common in moderate and severe than in mild CKD. This suggests that based on an ABI assessment, cardiovascular events are more commonly found in moderate and severe CKD. Low ABI values correlated with an increase in vascular access failure for hemodialysis. This condition is more common in the distal regions of arteriovenous anastomosis; indicating the extent of atherosclerosis. Low ABI values are closely related to generalize atherosclerosis of blood vessel walls.

The current study has its weaknesses. First, as we did not investigate consecutive patients, there might have been selection bias. The applicability of a new criterion ABI needs to be validated in clinical practice. The potential trade-off between diagnostic certainty and economic aspects must be well-balanced and may vary between different settings. Second, as recently reviewed by Urbina et al. [13] a number of gaps in our values CIMT exists that include which carotid segments provide the best information and cost-effectiveness of CIMT measures for the identification of high-risk children. Third, as a cross sectional study, co morbid factor was not evaluated simultaneously with ABI and stage of CKD. However, as far as we know this is the first study to investigate new criterion ABI ‘borderline’ in pediatric CKD and correlated with stages for CKD [14-18].

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge for Division of Pediatric Cardiology in H. Adam Malik Hospital.

References

- Arroyo D, Betriu A, Valls J, Gorris JL, Pallares V, et al. (2016) Factors influencing pathological ankle-brachial index values along the chronic kidney disease spectrum: the NEFRONA study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32(3): 513-518.

- Brady TM, Schneider MF, Flynn JT, Cox C, Samuels J, et al. (2012) Carotid intima-media thickness in children with CKD: results from the CKID study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1930-1937.

- Bauer M, Caviezel S, Teynor A, Erbel R, Mahabadi AA, et al. (2012) Carotid intima-media thickness as a biomarker of subclinical atherosclerosis. Swiss Med Wkly 142: w13705.

- KDIGO (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney International Supplements 3: 1-150.

- Brady TM, Schneider MF, Flynn JT, Cox C, Samuels J, et al. (2012) Carotid intima-media thickness in children with CKD: results from the CKiD study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1930-1937.

- London GM, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Pannier B, Safar ME, et al. (1996) Cardiac and arterial interactions in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 50: 600-608.

- Harambat J, Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ (2012) Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 2: 363-373.

- V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, Creager MA, (2012) Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: a Scientific statement from the American Heart Association Aboyans. Circulation 126(24): 2890-2909.

- Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ballew SH, Shlipak M, Katz R, et al. (2014) Subclinical atherosclerosis measures for cardiovascular prediction in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 26(2): 439-447.

- Newman AB, Siscovivk DS, Mamolio TA, Polak J, Fried LP, et al. (1993) Ankle arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the cardiovascular health study. Circulation 88(3): 837-845.

- O’hare AM, Glidden DV, Fox CS, Hsu C (2004) High prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in persons with renal insufficiency. Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999- 2000. Circulation 109(3): 320-323.

- McDermott MM, Liu K, Criqui MH, Ruth K, Goff D, et al. ( 2005) Anklebrachial index and subclinical cardiac and carotid disease the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol 162(1): 33-41.

- Urbina EM, Williams RV, Alpert BS, Collins RT, Daniels SR, et al. (2009) Noninvasive assessment of subclinical atherosclerosis in children and adolescent. Recommendation for standard assessment for clinical research a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 54(5): 919-950.

- Mitsnefes MM (2008) Cardiovascular complications of pediatric chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 23(1): 27-39.

- Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham risk score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta analysis. JAMA.2008; 300(2): 197-208.

- Bots ML, Sutton-Tyrrell K (2012) Lesson from the past and promises for the future for the carotid intima- media thickness. JACC. 60: 1599- 1604.

- Chen SC, Chang JM, Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Wang CS, et al. ( 2009) Significant correlation between ankle-brachial index and vascular access failure in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 128-134.

- Schaefer F, Wuhl E (2013) Pediatric Hypertension. In: Flynn JT, Ingelfinger JR, et al. (Eds.), Hypertension in chronic kidney disease. Springer Science Business Media, New York, USA, pp. 323-340.