Preliminary Clinical Validation of the UK English Version of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score in UK English-speaking female population of Newcastle, Great Britain

Jakhongir F Alidjanov1*, Henrique A Lima2, Adrian Pilatz1, Robert Pickard3, Kurt G Naber4, Yodgorbek U Safaev5 and Florian M Wagenlehner1

1Department of Urology, Clinic and Polyclinic for Urology, Pediatric Urology and Andrology, Justus-Liebig University, Germany

2Department of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

3Department of Cellular Medicine Newcastle University, United Kingdom

4Department of Urology, Technical University of Munich, Germany

5Outpatient Department, JSC “Republican Specialized Center of Urology“, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Submission: December 21, 2016; Published: January 10, 2017

*Corresponding Author: Jakhongir F Alidjanov, Outpatient Department, JSC "Republican Specialized Center of Urology”, Department of Urology, Clinic and Polyclinic for Urology, Pediatric Urology and Andrology, Justus-Liebig University, Rudolf-Buchheim-StraRe 7 35385 Giessen, Germany, Email: Jakhongir.Alidjanov@med.uni-giessen.de

How to cite this article: Alidjanov J F, Lima H A, Pilatz A, Pickard R, Naber K G, Safaev Y U, Wagenlehner F M. Preliminary Clinical Validation of the UK English Version of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score in UK English-speaking female population of the Newcastle, Great Britain. JOJ uro & nephron. 2017; 1(3): 555561. DOI: 10.19080/JOJUN.2017.01.555561

Abstract

Background: The Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS) was initially developed in Uzbek language for assessing acute cystitis (AC) symptoms' severity and effect on quality of life. The ACSS demonstrated high values of reliability and validity also when translated into other languages. We aimed to develop the UK English language version of the ACSS for validation in native English-speaking female respondents.

Methods: Translation of the ACSS from original Uzbek language into UK English was performed according to adopted international guidelines. The study included 18 native English-speaking females (5 patients; 13 controls) with mean age of 48.4±21.6 years. Reliability, validity and predictive ability of the ACSS were measured. Parametric and non-parametric statistical tests were used when appropriate. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Effect sizes were also measured. Comparative analysis was performed using Fisher's F-test and MannWhitney U-test. Diagnostic power was calculated using univariate ANOVA.

Results: The UK English version of the ACSS demonstrated high values of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.94) and responsiveness (sensitivity=0.80, specificity=0.77, diagnostic odds ratio=13.33). Power of the scale was 0.97. Mean scores were significantly higher in women with AC (23.0, 95% CI: 8.3-37.7) than in those without AC (5.9, 95% CI: 2.1-9.6) (P<0.01). Mean to very large effect size values (Cohen's d ranged 0. 73 to 2.90) were revealed for differences in magnitudes between groups.

Conclusion: The UK English version of the ACSS has demonstrated good to excellent values of reliability, validity, predictive ability, responsiveness and power for UK residents. Additional results obtained in a larger cohort of female respondents as well as outcome assessment are, however, desirable.

Keywords: Urinary tract infections; Females; Cystitis; Symptoms and signs; Questionnaires; Scores; Effect size calculations

Abbreviations: JSC: Joint-Stock Company; AUC: Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis; ACSS: Acute Cystitis Symptom Score; UTIs: Urinary Tract Infections; CI: Confidence Intervals; QoL: Quality of Life; UK: United Kingdom

Background

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common and widespread infectious conditions among women [1-3]. The vast majority ofthese women suffer from lower UTIs , mainly acute uncomplicated cystitis (AUC), with an incidence of 0.7 episodes per person/year in otherwise healthy premenopausal females and 0.07 episodes per person/year in postmenopausal women [4-5]. Female patients affected by AUC may have symptoms for more than 6 days with 2.4 days during which they cannot work because of restricted activity due to these disabling symptoms [6]. Clinical manifestations of AUC may vary as well as the diagnostic strategies among physicians [7-9]. Although painful urination (dysuria) is the key symptom of AUC, it might also be related to vaginal disorders. An acute onset of dysuria in combination with frequency and urgency in absence of vaginal discharge or vaginal irritation increases the probability of AUC up to more than 90%. Such a combination of symptoms makes it possible to diagnose AUC based on history alone [10-12]. In consequence systematized algorithms of consultation protocols, specified questionnaires and symptom diaries were introduced into clinical practice for diagnosis, assessment of symptom severity, impact of the quality of life and impairment of everyday activity [8,13-16].

The Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS) was developed for: a) detection and evaluation of severity of the AUC symptoms; b) assessing the impairment of everyday activity and quality of life caused by symptoms of AUC in women; c) differentiation of AUC from other disorders, presenting with similar symptomatology. . ACSS was initially developed in Uzbek language [17], and was further translated and clinically validated in Russian [18] and German [19] languages. In addition, the ACSS demonstrated promising capabilities in patient-reported outcome assessment, with applicability in both daily practice and in clinical studies [20]. The current article represents the results of the preliminary clinical validation of the "diagnostic” part of the UK English version of the ACSS, within a small pilot study in a native English-speaking female population (Patients and Controls) in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom.

Materials, Subjects and Methods

Acute cystitis symptom score

The original ACSS was developed as a patient's selfassessment tool consisting of 18 questions. The questions were categorized into four domains or "subscales”: a) typical symptoms (questions 1-5); b) differential diagnosis (questions 7-10); c) quality of life (questions 11-13); and d) additional questions for underlying conditions (questions 14-18). The second form of the ACSS ("follow-up” form) proposed for assessment of outcomes is the same as the first "diagnostic" form with the exception of one additional subscale ("Dynamics”), fashioned as multiple choice question for assessment of overall changes in patient's condition. For each multiple choice question in "Typical”, "Differential”, and "QoL” subscales close-ended answers are fashioned as a 4-point Likert-response-scale equipped with discrete numbers to assess severity of each symptom/sign. The scale ranges from 0 to 3, where 0 means absence of symptom or discomfort; 1 = symptom/sign/discomfort is present with mild severity (minimal awareness); 2 = symptom/sign/discomfort is present with moderate severity; 3= symptom/sign/discomfort is present with severe severity (hard to tolerate). The "Additional” section contains "yes/no” dichotomous-fashioned questions.

Process of translation

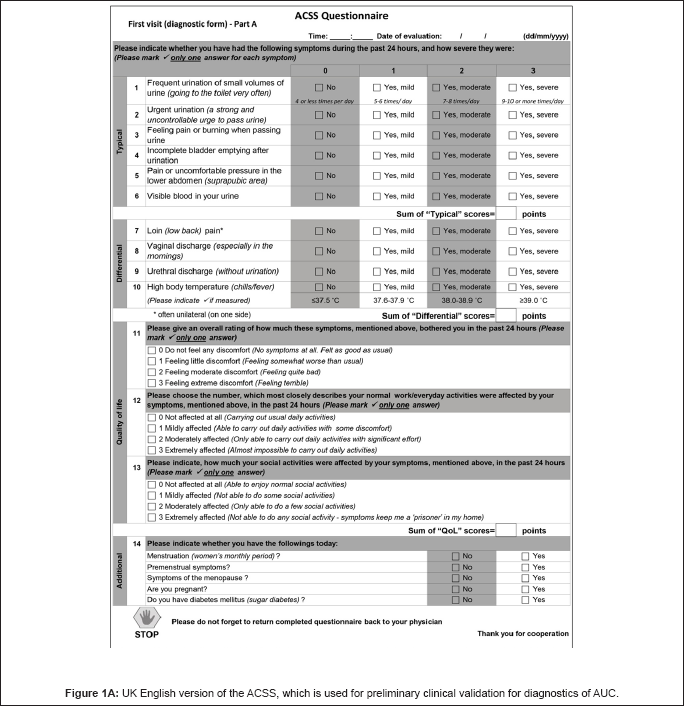

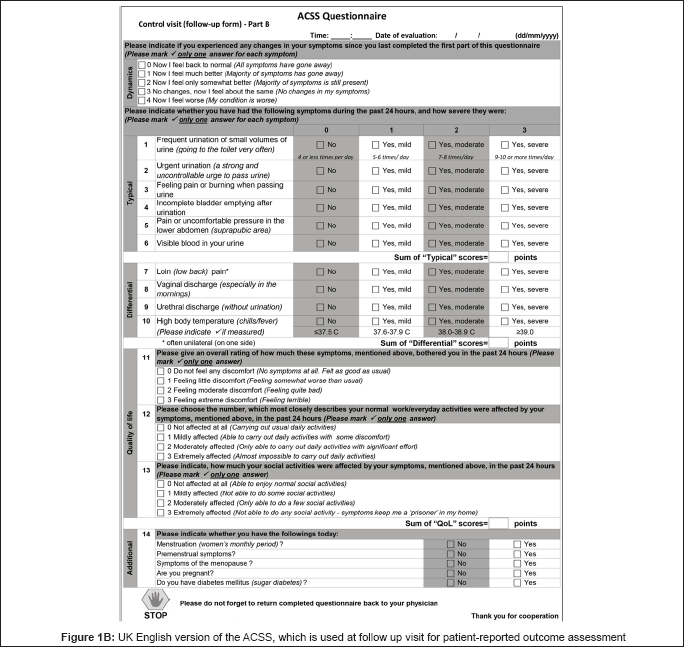

The process of linguistic validation of the ACSS from original Uzbek language into English, was performed according to the internationally approved Guidelines as published previously [18,19,21]. The current English translation of the ACSS was adapted slightly after interviewing 10 native UK Englishspeaking women to rule out any linguistic problem. It was also adapted in the subscale "Dynamics" [20] and was finally used for pilot clinical validation in the purpose of determining the applicability of the translated UK English version of the ACSS in native English-speaking population for diagnostics of AUC in women (Figures 1A and 1B).

Study respondents

Current study was performed as a part of a service evaluation of the health care organization initiated by National Health Service (NHS) of United Kingdom. Native UK English-speaking female respondents, 16 years of age and older, who were consulting a urologist because of bothersome recurrent lower urinary tract infections within the period between 17 June 2014 and 8 August 2014 were asked to take part in the study. As it was a non-interventional study and respondents were already completing other clinical questionnaires to help their care, the study was classed as a service development not requiring specific ethics approval. Women who agreed to complete the additional ACSS version were given a paper form of the questionnaire and were requested to complete it by themselves, independently. All respondents underwent routine clinical investigations such as ultrasound, urinalyses and urine culture of a mid-stream urine sample. The participants were divided into two groups (Patients or Controls) according to the physician's diagnosis based on presence or absence of typical symptoms, pyuria and bacteriuria at the time of questionnaire completion. Colony forming units >104 per milliliter of urine were considered microbiologically diagnostic in women presenting with the key symptoms of AUC [22]. The data from the paper-form questionnaires were then recorded in electronic form using PC software especially developed for the purpose of recording, storing and processing inputted data (e-USQOLAT).

Statistical analysis

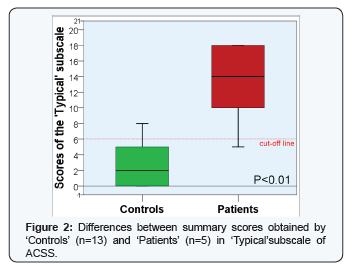

Ordinary descriptive statistics were used for the description of demographic characteristics of the study respondents. Normality of distributions was tested both numerically (by calculating skewness and kurtosis, Shapiro-Wilk test) and visually (Q-Q plots). Parametric and non-parametric statistical tests were used when appropriate. Reliability of the English version of ACSS was evaluated by calculating its internal consistency, interclass correlation (Cronbach's alpha) [23] and split-half reliability coefficients [24]. As it was calculated and resulted from our previous investigations [17-19], a sum score of 6 of the typical symptoms (Figure 2) was used as cut-off value for discriminating respondents into Patients and Controls. Validity and predictive ability of the ACSS were measured by the calculation of its responsiveness: sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals [25]. For comparative analysis of independent variables, Fisher's F-test [26] and Mann-Whitney U-test [27] were used. Power of the diagnostic test was calculated using univariate model ANOVA. A P-value equal or lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Substantive significance (effect size) was estimated using Cohen's d [28] and correlation coefficient (r) proposed by Rosenthal and Rosnow [29] and was reassessed by Hedge's g [30].

For statistical analysis the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) For Windows was used.

Results

Translation and linguistic validation

The final UK English ACSS version used in the study for diagnostics of AUC in women is presented in Figure 1A.

Study respondents

Eighteen female respondents with an average age (Mean±SD) of 48.4±21.6 (range 16 to 80) years agreed to complete the questionnaire. Further, according to physician's diagnosis, thirteen of them considered having no AUC, including one women with only asymptomatic bacteriuria, at the time of questionnaire completion were included and described as controls. The remaining five respondents with signs and symptoms of AUC and diagnosed by clinical and laboratory tests to suffer from AUC were included into the patients' group.

Sample characteristics

A Shapiro-Wilk's test [31] and visual inspection of normal Q-Q plots showed that almost all variables were distributed for both, Patients and Controls, with a skewness and kurtosis close to zero.

Pilot clinical validation

To assess reliability, validity and predictive ability of the UK English version of the ACSS, 18 copies of the paper-form of the UK English ACSS were handed out to the respondents and 18 copies were returned. All study respondents reported that all questions of the ACSS and proposed answers were clearly presented. Suggested changes were inserted: "visible blood in your urine" for 'haematuria'; 'menstruation (women's' monthly period)' for 'menses', 'premenstrual symptoms' for 'the premenstrual syndrome' and 'symptoms of the menopause' for 'menopausal syndrome'. No concerns regarding design or structure of the ACSS were reported. The adaptation in the subscale "Dynamics” was performed, since it was shown that these questions were not asked precisely enough and needed to be updated [20]. This part of the ACSS questionnaire (Figure 1B) used at follow up visits for patient-reported-outcome was, however, not clinically evaluated in this pilot study.

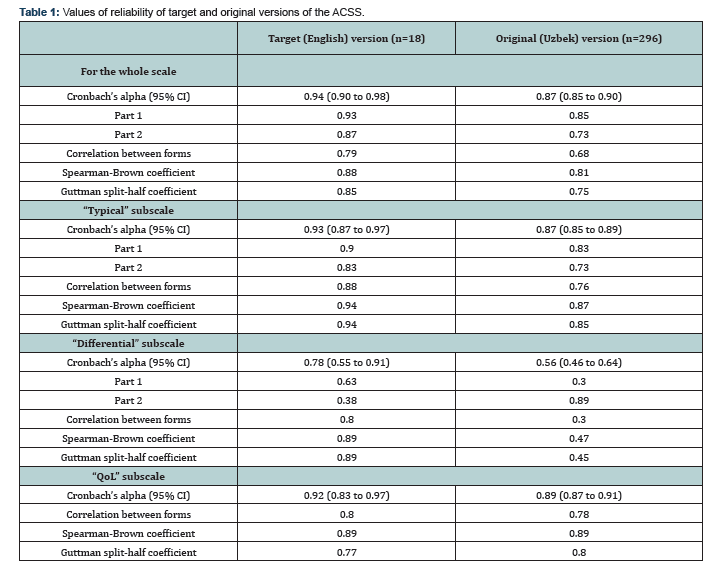

The summary scores of the "Typical” subscales of the two groups, with and without AUC, are presented in Figure 2. The summary score of 6 of the typical symptoms was used as cut-off between Patients and Controls with sensitivity and specificity of 0.80 (95% CI:0.38 to 0.96) and 0.77 (95% CI: 0.50 to 0.92), respectively. Positive likelihood ratio for revealing AUC was 3.47 (95% CI: 1.17 to 10.26) and negative likelihood ratio was 0.26 (95% CI: 0.04 to 1.54). Thus, diagnostic odds ratio was 13.33 (95% CI: 1.05 to 169.56). The interclass correlation coefficients (Cronbach's alpha) for the items of the UK English ACSS version was 0.56 (95% CI: 0.40 to 0.75) and 0.94 (95% CI: 0.90 to 0.98) for single and average measures, respectively (p<0.001). Other values of reliability tests were also high both for the whole scale and its subscales (Table 1).

Note: n- number of respondents; CI-confidence intervals.

Effect size calculations

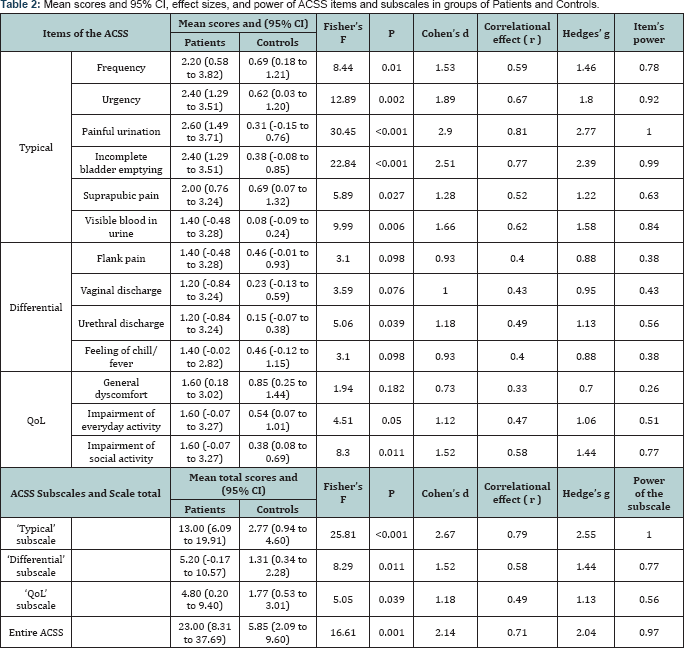

Calculation of the Cohen's d and Hedges' g values for all typical symptoms resulted in large effect sizes (from 1.28 to 2.90 for Cohen’s d; 1.22-2.77 for Hedges'g) with strong positive correlations (0.52 to 0.81 for Pearson's correlation coefficient: r ). Highest effect size values were expectedly obtained for painful urination (2.90 for Cohen's d, 2.77 for Hedges' g and 0.81 for Pearson’s r) and lowest values: for suprapubic pain and tenderness (1.28 for Cohen's d, 1.22 for Hedges’ g and 0.52 for Pearson's r). Differential symptoms also had from medium to large effect sizes (0.93-1.18 for Cohen’s d, 0.88-1.13 for Hedges' g and 0.40-0.49 for Pearson’s r). Small to large effect size values were obtained for "QoL" items (0.33-0.58 for Pearson's r).

Regarding sum scores of the subscales and total score of the ACSS, highest values of Cohen’s d were obtained for "Typical" subscale and total ACSS scores (2.67 and 2.14 respectively). Other values of effect sizes for these parameters were also high. Despite of low statistical significance for differences in "QoL" summary score between groups (P=0.039), large magnitude of the difference in scores between groups was revealed using effect size calculation (1.18 for Cohens d, 1.13 for Hedge’s g). More detailed information about results of calculations of effect size, power of the items, subscales and entire questionnaire are listed in (Table 2).

Comparative analysis

Despite of normal distribution of study variables, we have decided to use nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for comparative analysis due to small sample size. Comparative analysis resulted in statistically significant differences between scores gained by Patients and Controls in all items of the "Typical” subscale (P<0.05), excepting one regarding hematuria (Visible blood in your urine) (P=0.075). Statistically significant differences between groups were also revealed for summary scores of the "Typical” and "Differential” subscales, as well as for total ACSS score (P<0.05). Mean values and 95% confidence intervals for scores obtained by Patients and Controls in ACSS items, subscales and entire ACSS are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

For acute uncomplicated cystitis there is no generally accepted questionnaire available, which might be used as a diagnostic tool for the assessment of severity of symptoms, and its impact on quality of life. Our studies aimed to develop a highly sensitive, specific, and simple patient self-reporting questionnaire, assessing the symptoms of AUC and their impact on quality of life, differentiating AUC from other urogynecological disorders with similar symptomatology, and assessing treatment efficacy The ACSS is a reliable, valid and easy-to-use questionnaire which may help to diagnose AUC in primary healthcare settings and to assess treatment efficacy. It can be self-administered and completed in a short time by patients. Questions and versions of answers to every question are easy to understand and may be used for epidemiological surveys and/or drug studies.

However, the ACSS is not the first questionnaire in the area of UTIs. Earlier, two other questionnaires: the UTI Symptoms Assessment (UTISA) and the Activity Impairment Assessment (AIA): have been reported. While the UTISA evaluates the severity of lower UTI, the AIA estimates the impairment of activity in UTIs [13,14]. Unfortunately, important statistical information like sensitivity, specificity, responsiveness and discriminative ability has not been reported for both used together. The ACSS was developed and validated with these parameters taken into account. It also contains questions to differentiate AUC from other commonly community-acquired urological and gynecological diseases ('Differential' subscale) and for conditions which may affect therapy ('Additional' subscale). These additional subscales may add more accuracy and be useful for epidemiological surveys.

The clinical validation of the original (Uzbek) version of the ACSS was performed in 286 female respondents and resulted in excellent values of reliability, responsiveness, discriminative ability and psychometric characteristics of the questionnaire and its subscales [17]. Results of the process of the clinical validation of the Russian (83 respondents) [18] and German (36 respondents) [19] versions showed very similar results to the initial Uzbek version. Therefore the two translated versions of the ACSS were recognized as valid and reliable as the original one. A sum of "Typical” scores equal to 6 and higher was also considered as discriminative cut-off value due to optimal values of responsiveness and diagnostic accuracy as revealed in our previous studies [17-19]. Due to small sample size of the current study, we decided to use effect size calculations to determine applicability of comparative analysis of our variables.

Estimation of effect sizes is initially developed mainly for meta-analyses, e.g. for justification of including small samples into the analysis together with larger one sand thus is uncommon in validation, single center based clinical trials and other research reports in the social sciences [30,32-33]. We have used calculation of effect sizes in the purpose of avoiding of Type II (beta) errors. Fortunately, our measurements resulted in values varying from medium to large effect sizes, which meant that means of our variables differed between groups and variables, might be considered as suitable for comparisons. Because of the small sizes of the samples, we have used nonparametric comparative tests, notwithstanding normal distribution of the variables. Statistically significant differences between the two groups (Patients and Controls) obtained for the sum scores of the "Typical” and "Differential” subscales and for the total scores of the ACSS testify the discriminative ability of the translated UK English ACSS version. Large effect size values revealed for all domains of the ACSS, including "QoL" subscale testifies for substantive significant differences between groups in spite of relatively lower statistical significance which may be resulted owing to small sample size and thus indication of the P value alone might be not enough [34].

The main limitation of the current study was the small number of respondents (Patients and Controls) and that the ACSS could not be assessed in follow-up visits for evaluation of outcomes. Nevertheless the results of this pilot study are promising and very similar to those found in the validation for the other three languages. It can be expected that the UK English ACSS version, if clinically validated in a larger population, will become a very important tool for clinical diagnosis of AUC as a base for rational empiric therapy, but could also be used in clinical studies for outcome measurements.

Conclusions

The ACSS originally developed and validated in Uzbek language and thereafter translated and validated also in Russian and German languages in the aims of the assessment of the severity of symptoms in women with AUC and their impact on quality of life as well as to differentiate from other urogenital disorders with the possibility to monitor treatment efficacy. In the current pilot study a UK English version of the ACSS was tested in 18 female respondents (5 with AUC and 13 without) and showed similar good values of reliability, validity, predictive ability and responsiveness as the former already validated versions. Additional results, however, obtained in a larger group of female patients and controls with outcome assessment would be desirable.

Ethical issues

Since the current study was registered as an audit for service development purposes, ethical approval was not deemed necessary and not submitted for Ethical Committee assessment. All respondents were invited to participate by clinical staff not connected with the evaluation. Those participants, who were interested, provided verbal consent and there was full anonymization of the collected information.

Authors contributions

JFA participated in translation of the ACSS into English, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript, participated in its revision and final reading. HAL carried out the recruitment of study respondents, questionnaire survey, performed preliminary statistical analysis and participated in revision of manuscript. AP participated in revision of the ACSS translated into English, helped to draft the manuscript, participated in its design, revision and final reading. RP participated in study design and coordination, revised the ACSS translated into English, helped to draft the manuscript, participated in its design, revision and final reading. KGN conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, revised the ACSS translated into English, helped to draft the manuscript, participated in its design, revision and final reading. YUS participated in the process of translation of the ACSS, statistical analysis and revision of backward translated version of the ACSS. FMW participated in study design and coordination, revised the ACSS translated into English, helped to draft the manuscript, participated in its design, revision and final reading.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants of the study for their contribution. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Prof. Dmitriil Aroustamov (former director of RSCU) for his priceless support and moral assistance. JFA expresses his heartfelt gratitude to European Urological Scholarship Programme (EUSP) and personally to Ms. Angela Terberg for their support in receiving a 1-year research grant for Clinical/ Lab Scholarship in the Justus-Liebig University, Clinic and Polyclinic for Urology, Pediatric Urology and Andrology.

The ACSS is copyrighted by the Certificate of Deposit of Intellectual Property in Fundamental Library of Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent (Registration number 2463; August 26, 2015) and the Certificate of the International Online Copyright Office, European Depository, Berlin, Germany (Nr. EU-01-000764; October 21, 2015).

References

- Schappert SM, Rechtsteiner EA (2011) Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2007. Vital Health Stat 169: 1-38.

- Patton JP, Nash DB, Abrutyn E (1991) Urinary tract infection: economic considerations. Med Clin North Am 75(2): 495-513.

- Nicolle LE, Strausbaugh LJ, Garibaldi RA (1996) Infections and antibiotic resistance in nursing homes. Clin Microbiol Rev 9(1): 1-17.

- Hooton TM, Scholes D, Hughes JP, Winter C, Roberts PL, et al. (1996) A prospective study of risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infection in young women. N Engl J Med 335(7): 468-474.

- Jackson SL, Boyko EJ, Scholes D, Abraham L, Gupta K, et al. (2004) Predictors of urinary tract infection after menopause: a prospective study. Am J Med 117(12): 903-911.

- Foxman B, Frerichs RR (1985) Epidemiology of urinary tract infection: I. Diaphragm use and sexual intercourse. Am J Public Health 75: 13081313.

- Heytens S, De Sutter A, De Backer D, Verschraegen G, Christiaens T (2011) Cystitis: symptomatology in women with suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infection. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 20(7): 1117-1121.

- Malterud K, Baerheim A (1999) Peeing barbed wire. Symptom experiences in women with lower urinary tract infection. Scand J Prim Health Care 17(1): 49-53.

- Berg AO (1991) Variations among family physicians' management strategies for lower urinary tract infection in women: a report from the Washington Family Physicians Collaborative Research Network. J Am Board Fam Pract 4(5): 327-330.

- Stamm WE, Hooton TM (1993) Management of urinary tract infections in adults. N Engl J Med 329(18): 1328-34.

- Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL, Fihn SD, Saint S. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA 287(20): 2701-2710.

- Fauci AS (2008) Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 17th (edn), McGraw-Hill Medical, New York.

- Clayson D, Wild D, Doll H, Keating K, Gondek K (2005) Validation of a patient-administered questionnaire to measure the severity and bothersomeness of lower urinary tract symptoms in uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI): the UTI Symptom Assessment questionnaire. BJU Int 96(3): 350-359.

- Wild DJ, Clayson DJ, Keating K, Gondek K (2005) Validation of a patient- administered questionnaire to measure the activity impairment experienced by women with uncomplicated urinary tract infection: the Activity Impairment Assessment (AIA). Health Qual Life Outcomes 3: 42.

- Little P, Merriman R, Turner S (2010) Presentation, pattern, and natural course of severe symptoms, and role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance among patients presenting with suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infection in primary care: observational study. Bmj 340: b5633.

- Schauberger CW, Merkitch KW, Prell AM (2007) Acute cystitis in women: experience with a telephone-based algorithm. WMJ : official publication of the State Medical Society of Wisconsin 106(6): 326-329.

- Alidjanov JF, Abdufattaev UA, Makhsudov SA, Pilatz A, Akilov FA, et al. (2014) New self-reporting questionnaire to assess urinary tract infections and differential diagnosis: acute cystitis symptom score. Urol Int 92(2): 230-236.

- Alidjanov JF, Abdufattaev UA, Makhmudov D, Mirkhamidov DKh, Khadzhikhanov FA, et al. Development and clinical testing of the Russian version of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score-ACSS. Urologiia (6): 14-22.

- 19. Alidjanov JF, Pilatz A, Abdufattaev UA, Wiltink J, Weidner W, et al. (2015) German validation of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score. Urologe A 54(9): 1269-1276.

- Alidjanov JF, Abdufattaev UA, Makhsudov SA, Pilatz A, Akilov FA, Naber KG, et al. (2016) The Acute Cystitis Symptom Score for Patient- Reported Outcome Assessment. Urol Int 97(4): 402-409.

- Acquadro C, Conway K, Giroudet C, Mear I (2004) Linguistic Validation Manual for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Instruments. MAPI Institute: Kluwer Academic Publishers, France, pp. 184.

- Kunin CM (1997) Urinary Tract Infections: Detection, Prevention, and Management. 5th (edn), Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, USA pp. 115.

- Cronbach LJ (1947) Test reliability; its meaning and determination. Psychometrika 12(1): 1-16.

- Cronbach LJ (1946) A case study of the split-half reliability coefficient. J Educ Psychol 37(8): 473-480.

- Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB (1991) Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol 44(8): 763-770.

- Fisher RA (1954) Statistical methods for research workers. 12th (edn), Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh.

- Mann HB, Whitney DR (1947) On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. 1947. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 18(1): 50-60.

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd (edn), Hillsdale, L Erlbaum Associates.

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL (1984) Essentials of behavioral research: methods and data analysis. 3"1 (edn), McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Hedges LV, Olkin I (1985) Statistical methods for meta-analysis, 1st (edn) Academic Press, Orlando, pp. 369.

- Shapiro SS, Wilk MB(1965) An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52(3-4): 591-611.

- Capraro RM, Capraro MM (2002) Treatments of effect sizes and statistical significance tests in textbooks. Educational and Psychological Measurement 62(5): 771-782.

- Volker MA (2006) Reporting effect size estimates in school psychology research. Psychology in the Schools 43(6): 653-672.

- Sullivan GM, Feinn R (2012) Using Effect Size-or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J Grad Med Educ 4(3): 279-282.