The Effect of Timing of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Following Thrombolytic Therapy on the Outcome of Patients Presenting with ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Ehab A Elhefny1, Ahmad Magdy K elden2, Moustafa I Mokarrab3, Ashraf A Abdelfattah4, Ahmad M Alkonaissi5* and Mohammad S Gassar5

1Professor of Cardiology, Faculty of medicine, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

2 Professor of Cardiology, National Heart Institute center, Egypt

3Assistant professor, Faculty of medicine, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

4Lecturer of Cardiology, Faculty of medicine, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

5Department of Cardiology, National Heart Institute center, Egypt

Submission: April 26, 2019; Published: May 14, 2019

*Corresponding author: Ahmad M Alkonaissi, Al-Azhar University-Faculty of medicine and National Heart Institute center, Lebanon square, Almohandeesin, Cairo, Egypt

How to cite this article:Ehab A E, Ahmad M K e, Moustafa I M, Ashraf A A, Ahmad M A, et al. The Effect of Timing of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Following Thrombolytic Therapy on the Outcome of Patients Presenting with ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Cardiol & Cardiovasc Ther. 2019; 13(5): 555875. DOI: 10.19080/JOCCT.2019.13.555875

Abstract

Background: Although primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the most preferred reperfusion method for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction, pharmaco-invasive strategy is considered a valid alternative to PPCI. Our main objective in this study was to assess the early and 6-month outcomes of ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients managed by pharmaco invasive reperfusion where PCI was done at 3 different timings to see the effect of timing of PCI after thrombolytic therapy up to 24 hours. Almost all studies done to identify the proper timing for intervention in pharmaco-invasive strategy are based on patients receiving rTPA. No study was done -up to our knowledge- using streptokinase.

Methods: Accordingly, we randomized three hundred patients with a diagnosis of anterior ST segment elevation myocardial infarction admitted to CCU in National Heart Institute hospital and Sayed Galal university hospital. They received thrombolysis by using streptokinase (1, 200000 IU) and then referred to catheterization laboratory for intervention after thrombolysis to into 3 groups:

• Group A: 100 patients had intervention at 3-10 hours post thrombolysis.

• Group B: 100 patients had intervention at 10.1-17 hours post thrombolysis.

• Group C: 100 patients had intervention at 17.1-24 hours post thrombolysis.

We studied the incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE); (Death, Stroke, Severe and life-threatening bleeding, Reinfarction, Maximal Killip class ≥ II) and LVEF in the acute stage, and 6 months outcome of survival, angina requiring revascularization, and LVEF as primary end points. Development of life-threatening arrhythmias, heart failure symptoms, and target lesion revascularization as secondary end points.

Results: We found that Group A patients had the lowest incidence of MACE (Death; 16%, Pvalue 0.041, Maximal Killip class ≥II; 46%, P-value <0.001 severe and life threatening bleeding; 2%, P-value 0.019) and highest median EF 40 (15 - 65) <0.001, Group B patients had almost similar MACE rates and 2nd high median LVEF 36 (20 - 65) P-value<0.001, while Group C patient had the highest MACE rates and lowest median LVEF 30 (20 - 52) Pvalue<0.001. Regarding 6 month follow up we found statistically significant survival benefit in Groups A & B compared to Group C (All-cause mortality; 13%, 13%, 27.3% respectively overall P-value 0.037) also we found benefits related to target lesion revascularization; (P-value<0.001), and symptomatic heart failure (P-value<0.001). LVEF medians were the same in Groups A & B and least in group C (P-value <0.001).

Conclusion: We recommend that patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy using streptokinase - which is still used in many countries around the world- to be subjected to catheter-based intervention as early as possible, namely within 3-17 hours after fibrinolysis as any delay of the process will have a significant negative impact on their short and long term MACE.

Keywords: Thrombolytic Therapy; Myocardial Infarction; Death; Stroke; Severe; Life-threatening bleeding

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the recommended default reperfusion strategy for patients seen in the early hours following the onset of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). From a practical point of view, however, primary PCI requires availability of cardiologists, nurses and technicians 24 hours a day and 7 days a week, which may still be a goal difficult to achieve in many areas or countries, and thrombolytic therapy is still widely used. In the past 10 years, evidence has been brought that fibrinolytic treatment should not be used as an alone therapy, but rather as part of a pharmacoinvasive strategy, with the patients referred to PCI-capable facilities after fibrinolysis, to perform coronary angiography and secondary PCI, when necessary [1].

Several recent studies suggest that coronary angiography and PCI performed between 3 and 24 hours after administration of fibrinolytic therapy, in case of successful reperfusion, reduces the risk of new ischemic events. As now mentioned in the guidelines, if fibrinolysis is indicated, it needs to be followed by an early coronary angiography and intervention and called (Routine early PCI after successful thrombolysis 2-24 hours) and (rescue PCI) after failed fibrinolysis. Because of the absence of cross-linking of fibrin in the fresh occlusive clot, such a strategy is especially effective in patients presenting early after symptom onset [2,3].

The aim of this study was to assess the early in-hospital and 6-month outcomes of anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients according to the use of three different protocols of pharmaco-invasive reperfusion in the acute stage based on timing of PCI after thrombolytic therapy (namely with streptokinase). Almost all studies done to identify the proper timing for intervention in pharmaco- invasive strategy are based on patients receiving rTPA. No study was done -up to our knowledge- using streptokinase.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the cardiology department of the National Heart Institute hospital-Cairo and, and Sayed Galal hospital (Al-Azhar university hospital) comprised 300 patients who presented to the emergency department during the period from June 2016 to March 2018.

Study Population

Patients were eligible for enrollment in the study if they presented within 3 hours of symptom onset of STEMI defined as at least 1 chest pain episode lasting at least 20 minutes, demonstrated acute anterior STEMI on their qualifying ECG with unequivocal changes (≥0.1 mV of ST-segment elevation in ≥2 adjacent limb leads or ≥0.2 mV in ≥2 contiguous precordial leads or new pathological Q waves) on surface electrocardiogram on admission and could not undergo PPCI within 1 hour after first medical contact and did receive thrombolytic therapy up to a maximum of 12 hours from the onset of chest pain; with no contraindication for either thrombolytic therapy and PPCI. Additionally, patients who were thrombolysed more than 6 hours from chest pain onset were given priority to be enrolled in group A.

We excluded patients underwent PPCI within 1 hour of chest pain onset. Patients who had previous MI within 6 months of presentation. Cardiogenic shock at presentation (systolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg, unresponsive to fluids, or necessitating catecholamines). Electrical instability (second- and third-degree heart block, recurrent VT, VF). Age > 70 years. Diabetes Mellitus: in order to exclude small and multi-vessel disease. Inability to comply with study procedures; and unwillingness or inability to provide written informed consent for participation. Renal impairment and patients on regular dialysis. Severe congestive heart failure and/or pulmonary edema. Previous CABG.

Study Protocol

All eligible STEMI patients (three hundred) were reperfused by pharmaco-invasive approach and they were randomized to 3 different groups A, B and C except patients in whom streptokinase was given more than 6 hours from chest pain, they were given priority to be enrolled in group A. Study groups were classified according to the timing of coronary angiography and intervention after thrombolysis namely with streptokinase as follows:

• Group A: 100 patients were referred to catheterization laboratory after fibrinolysis at 3-10 hours (33.33%).

• Group B: 100 patients were referred to catheterization laboratory after fibrinolysis at 10.1-17 hours (33.33%).

• Group C: 100 patients were referred to catheterization laboratory after fibrinolysis at 17.1-24 hours (33.33%).

Endpoints

In-hospital complications and major adverse cardiac events; Re- infarction, Death, cerebrovascular accidents, Maximal Killip class ≥ II, Severe bleeding and life-threatening bleeding. Left ventricular ejection fraction. Six months: Survival, Angina requiring hospitalization, Left ventricular ejection fraction (primary endpoints). Development of symptomatic congestive heart failure; Development of significant arrhythmias. Target lesion revascularization (TLR) (secondary endpoints).

Statistical analysis

The collected data was revised, coded, tabulated and computed by using Statistical package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data was presented and suitable analysis was done according to the type of data obtained for each parameter. Descriptive statistics; Mean Standard deviation (± SD) and range for parametric numerical data, frequency and percentage of non-numerical data. Analytical statistics; ANOVA test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between more than two study group means. Post Hoc Test is used for comparisons of all possible pairs of group means. Chi-Square test was used to examine the relationship between two qualitative variables. Fisher’s exact test: was used to examine the relationship between two qualitative variables when the expected count is less than 5 in more than 20% of cells. Kruskal-Wallis test used when the normality, homogeneity of variances, or outliers’ assumptions for One-Way ANOVA are not met. Wilcoxon signed-rank test is the nonparametric test equivalent to the dependent t-test. It is used to compare two sets of scores that come from the same participants. This can occur when we wish to investigate any change in scores from one time point to another, or when individuals are subjected to more than one condition. P- value: level of significance; >0.05: Non-significant (NS). P< 0.05: Significant (S). P<0.01: Highly Significant (HS).

Results

Comparisons of baseline clinical characteristics

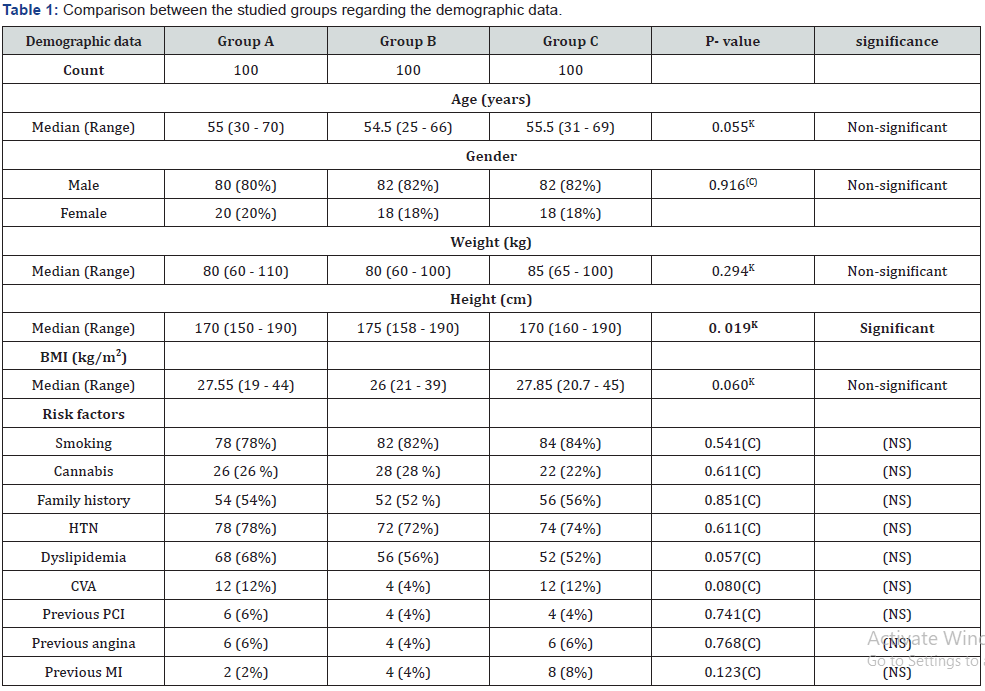

Baseline characteristics of included patients were well balanced as regards CAD risk factors and demographics; apart from, height (p-value:0.019) which is of negligible effect on the characteristics of included patients as evidenced by statistically insignificant variation in between groups in body mass index BMI as illustrated in Table 1.

KKruskal Wallis test.

(C)Chi-square test.

Comparison of coronary angiography and TIMI flow characteristics

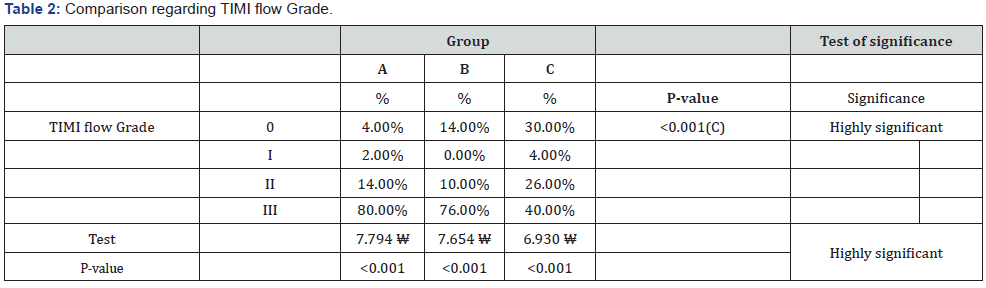

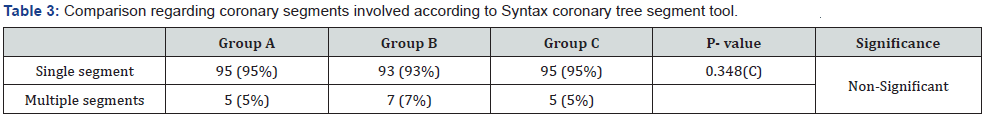

At angiography there were statistically highly significant differences regarding final TIMI flow (after intervention) with highest percentage of TIMI flow III in Group A & B and least in Group C meanwhile there were significant statistical differences regarding final TIMI flow 0; where highest percentage of TIMI flow 0 (No-flow) in Group C and least in Group A and B as illustrated in Table 2. Also, there were no statistically significant differences on testing in between groups regarding single coronary segment versus multi-segment involvement according the syntax coronary segment tool as illustrated in Table 3.

(C)Chi-Square test of significance.

(W)Wilcoxon signed rank test.

(C)Chi-square test.

Comparison between the studied groups regarding the outcome of acute stage

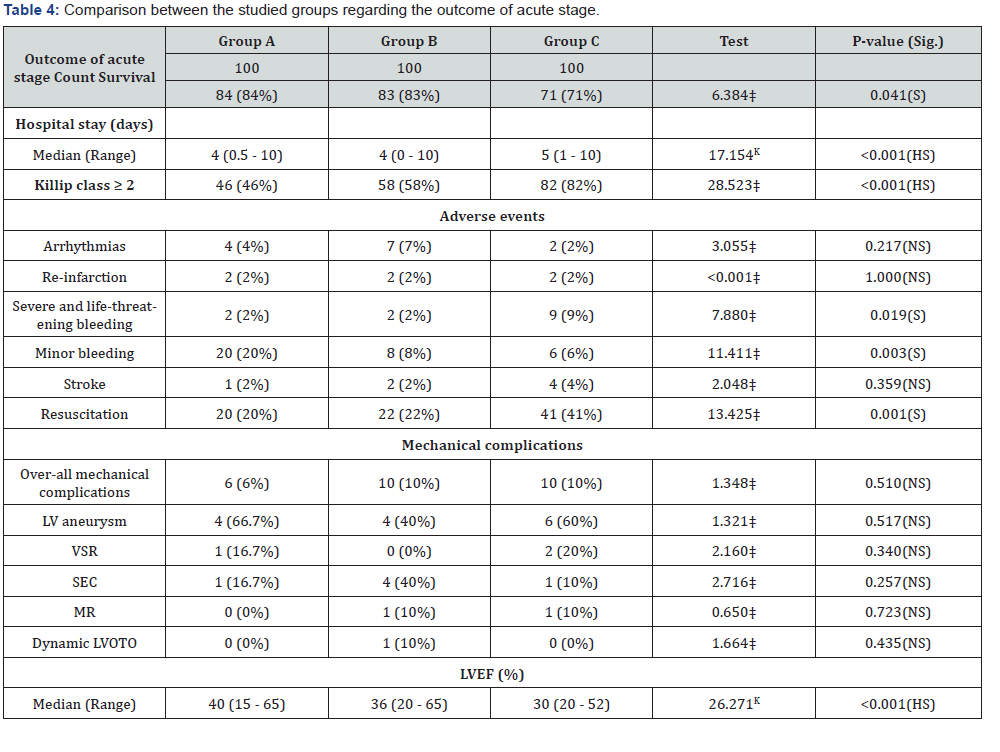

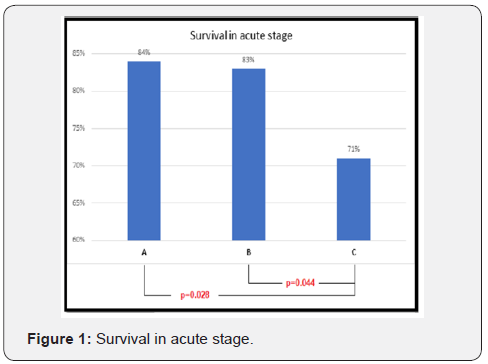

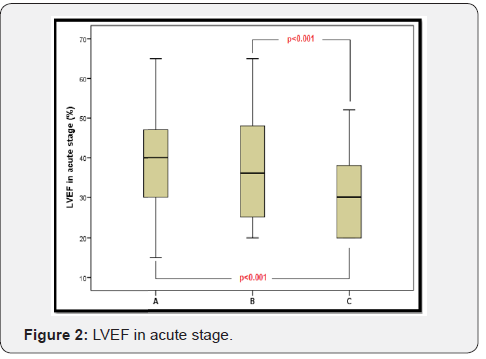

There was a statistically significant difference in between groups as regards survival in the acute stage which was highest in group (A) patients, followed by in group (B) and lowest in group (C), with significant difference on testing between group A and C /and B and C suggesting prominent survival advantage in group A and B over C as illustrated in Table 4 and Figure 1. As regards other major adverse cardiac events; there was no statistical significant difference in the incidence of re-infarction, cerebrovascular accidents and significant arrhythmias, however there was statistically significant difference as regards incidence of severe and life threatening bleeding with lowest incidence among groups (A) and (B) patients, and highest in group (C) patients; there was also one in the percentages of resuscitated cases in each group. Highest percentage in group (C) patients and lowest in group (A) as illustrated in Table 4. As regards left ventricular ejection fraction in the acute stage (immediately after intervention) of included patients there were statistically significant differences with highest median in Group (A) patients and least median in Group C patients as illustrated in Table 4 & Figure 2. Regarding the incidence of mechanical complications detected by trans-thoracic echocardiography, there was an overall incidence of 2% in the included patients; statistically there were no testing significant differences in between groups as described in Table 4.

KKruskal Wallis test.

‡Chi-square test.

p< 0.05 is significant.

Sig.: significance.

the outcome after six months

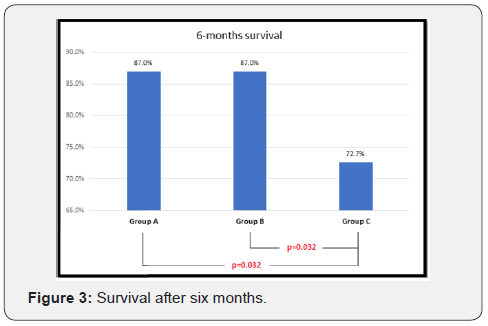

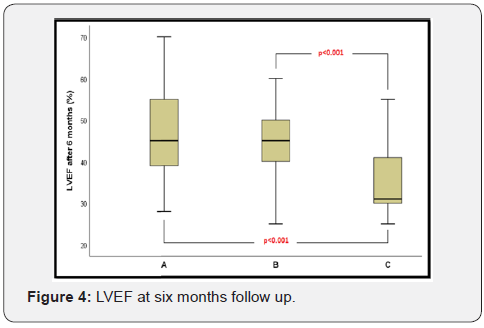

As regards survival at 6 months follow up there was statistically significant difference on testing in between groups with highest survival percentage in group (A) and (B) compared to group C as illustrated in Figure 3. there were statistically non-significant differences regarding Angina requiring revascularization of included patients. However, there were statistically highly significant differences in between groups regarding symptomatic heart failure according to (NYHA functional class ≥II), with highest percentage of cases in group C patients. There were also highly significant statistical differences in between groups as regarding median LVEF at 6 months follow up with least median LVEF in group (C) patients and equal median LVEF in group (A) and group (B) patients as illustrated In Table 5 and Figure 4.

Discussion

The optimal timing for angiographic assessment and management after fibrinolysis in STEMI patients managed using the pharmaco-invasive approach is highly relevant to cardiologists at receiving PCI centers [4]. Early PCI after fibrinolysis or a pharmaco-invasive approach has been defined in recent trials then concluded in the guidelines as fibrinolysis followed by catheterization within 24 hours where primary PCI was not feasible [5]. This was confirmed by a meta-analysis which included 5 clinical trials comparing early PCI to standard treatment after fibrinolysis where primary PCI was not feasible that proved the effectiveness of pharmaco-invasive strategy. All of the included five trials required transfer to PCI capable centers [6]; this is discussed more in details elsewhere in this article.

TRANSFER-AMI Trial, The Trial of Routine Angioplasty and Stenting after Fibrinolysis to Enhance Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (main landmark trial for pharmacoinvasive reperfusion) and others have shown that STEMI patients presenting to a non-PCI hospital, who cannot be transferred for primary PCI within 90 minutes, benefited from a pharmacoinvasive reperfusion strategy of routine PCI within 6 hours of initial thrombolytic therapy compared with standard-alone fibrinolytic therapy [6].

The European society of cardiology STEMI guidelines in 2017 stated that after fibrinolysis, it is recommended to transfer the patients to a PCI center. In cases of failed Thrombolytic therapy, or if there is evidence of re-occlusion or re- infarction with recurrence of ST-segment elevation, immediate angiography and rescue PCI is indicated. In this setting, re-administration of fibrinolysis has not been shown to be beneficial (discouraged). Even if it is likely that Thrombolysis will be successful (ST-segment resolution > 50% at 60-90min; typical reperfusion arrhythmia; and resolution of chest pain), a strategy of routine early angiography is recommended if there are no contraindications. Several randomized trials and meta-analyses have shown that early routine angiography with subsequent PCI (if needed) after fibrinolysis reduced the rates of re-infarction and ongoing ischaemia compared with a ‘watchful waiting’. The main benefits of early routine PCI after fibrinolysis were seen in the absence of an increased risk of adverse events (stroke or major bleeding), and across patient subgroups. Thus, early angiography with subsequent intervention if indicated is also the recommended standard of care after likely successful fibrinolytic therapy [3].

Important issue is the optimal time delay between successful lysis and PCI; there was a wide variation in delay in trials, from a median of 78 minutes (1.3 hour) in the Combined Angioplasty and Pharmacological Intervention versus Thrombolytics ALone in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAPITAL AMI) trial to 17 hours in the (GRACIA)-1 and STREAM trials. Based on this analysis, as well as on trials having a median delay between start of fibrinolysis and angiography of 2- 17h, a time window of 2-24h after successful lysis is recommended in the guidelines [3].

In our study the mean age of enrolled patients was 53.24 ± 9.51. All cases enrolled were given standardized fibrinolysis (streptokinase; protocol of 1.5 million IU over 30-60 min intravenously). All stent used were bare metal stents. The use of additional GP IIB/IIIA was left to the operator opinion whether intracoronary or intravenous administration after PCI.

Major adverse cardiac events (MACE)

In our study we found that patients randomized to coronary angiography with possible intervention after fibrinolysis in early hours after the event which is group (A) and group (B) patients benefited as regards primary outcome parameters. Both groups were associated with better survival rates in the acute stage (P-value; 0.041), congestive heart failure and cardiogenic shock (Maximal Killip class ≥II) rates (P-value <0.001). These findings were not associated with increased incidence of severe and lifethreatening bleeding when compared to group and (C) patients. Additionally, group (C) patients had the largest number of resuscitated cases compared to almost similar numbers in groups (A) & (B) (P- value; 0.001). Re-infarction incidence was the same all through in the sample population (P-value; 1). CVA didn’t show statistically significant incidence (P- value; 0.359).

These findings were in agreement with the results from TRANSFER MI trial as regards the acute stage outcome (MACE) except for re-infarction were early routine PCI patients benefited in TRANSFER MI. The TRANSFER MI trial investigated larger sample of patients. They randomized 1059 high-risk patients who had a myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation and who were receiving fibrinolytic therapy at centers that did not have the capability of performing PCI to either standard treatment (including rescue PCI, if required, or delayed angiography) or a strategy of immediate transfer to another hospital and PCI within 6 hours after fibrinolysis. The main differentiating feature in our study is the lack of inclusion of patients based on high risk features e.g. Anterior STEMI, Inferior STEMI with at least one; systolic blood pressure < 100 mm Hg, Heart rate > 100 beats per minute, Killip class II or III … etc. Also, patients were enrolled in our study without being classified (failed or succeeded thrombolysis).

Left Ventricular Function

As regards LV function in the acute stage, group (A) had the highest median LVEF; 40% with a range of (15 - 65) this was followed by group (B) 36% (20 - 65). Group (C) had the lowest median 30% (20 - 52) (P-value <0.001). LVEF findings were not addressed in landmark trials including the TRANSFER MI trial.

TIMI flow grade (TFG)

Invasive assessments in all groups provided us with additional information where group A patients had the highest percentage of final TIMI flow grade III 80/100(80%), and group C had the highest percentage of final no flow 30/100 (30%) (P<0.001), suggesting better final angiographic outcome with group A patients, these findings were in disagreement with results from TRANFER-AMI; where there were no statistical significant variation between standard treatment and routine PCI after thrombolysis groups regarding TIMI flow grade (in TRANSFER- AMI; Tenectplase was the thrombolytic agent used and stents used were bare metal and drug eluting stents, but bare metal stents were the major number used).

More conclusions could be driven from the association of invasive assessment results (final TIMI flow P-value <0.001), clinical assessment results (maximal Killip class during admission ≥ II); group (A) 46/100(46%), group (B) 58/100(58%), group C 82/100(82%) (P-value <0.001) and echocardiographic assessment results (LVEF) (P-value <0.001), which point toward clear benefit of group (A) and group (B) patients more than group (C) patients. So, in our study only clinical end points in the acute stage agree with results from TRANSFER MI trial (30 days efficacy) and disagree with 6 months efficacy end points.

Severe and life-threatening bleeding

As regards severe and life-threatening bleeding the general incidence of bleeding in our sample is 4.3% and statistically there was significant differences in between groups suggesting increase in the incidence of severe and life-threatening bleeding in group (C) patients (P value; 0.019). These findings were consistent with CARESS-In-AMI trial and TRANSFER MI trial results.

Accordingly patients referred to angioplasty after fibrinolysis who had angiography and angioplasty 3-17 hours after fibrinolysis namely with streptokinase, were associated with significantly better survival outcome in acute stage, Killip class status, better left ventricular function measured by EF by trans- thoracic echocardiography without increase in the incidence of severe and life threatening bleeding events, which could be explained by the earlier and more efficient reperfusion of infarct related artery, better TIMI flow, vessel patency, and lesser need for glycoprotein II B III A inhibitors.

Follow up

Survival: on 6 months follow up of the sample of patients this study found survival differences between patient’s groups, group (A) and (B) patients had the best survival 87%,87% respectively, group (C) patients had 72.7% (P-value; 0.037). Regarding Target lesion revascularization; Groups (A) and (B) had 4.5% and 3% respectively and significantly increased incidence in group (C) 22.9% (P- value; <0.001). No statistically significant differences were found regarding angina requiring hospitalization after discharge (P-value 0.122), these findings proves that the benefits of early intervention (Groups A and B) after thrombolysis were persistent beyond the acute stage i.e. 6 months survival follow up.

Chronic symptomatic heart failure: on the 6 months follow up, there was statistically significant high incidence of symptomatic heart failure (NYHA class ≥ II) in group (C) patients (54.2%) versus groups (A) and (B) had 17.9% and 14.9% respectively (P-value; <0.001).

Ejection fraction showed the median 35% range of (25 - 55) in group (C) versus 45% (28 - 70) in group A and 45% (20 - 60) in group B (P-value <0.001).

So early PCI after fibrinolysis (3-17 hours) improved survival and EF in acute stage and at 6 months follow up. And late PCI after fibrinolysis (Group C) impacted 6 months follow up LVEF, TLR and symptomatic heart failure when compared to early PCI in Groups A & B.

The FAST MI trial demonstrated that when used early after the onset of symptoms (<220 min), a pharmaco-invasive strategy resulted in an in-hospital, 30- day, and 1-year survival rates that were almost similar to those of primary PCI [1]. Also, the STREAM (Strategic Reperfusion Early After Myocardial Infarction) investigators demonstrated comparable 30-day clinical outcomes when STEMI patients within 3 h of symptom onset received pre-hospital fibrinolysis a median of 100 min after the onset of symptoms was comparWhen comparing our results to those from SRTEAM and FAST MI trials, time targets and prehospital thrombolysis are the main differences, however conclusions regarding the benefits of early intervention after thrombolysis are the same. Moreover, the LVEF findings in the acute stage and the 6 months follow up provide more evidence of benefits.

Conclusion

Our Study showed that pharmaco-invasive strategy with early PCI after fibrinolysis within 24 hours constitutes a valid reperfusion strategy for patients presenting with ST elevation Myocardial infarction, where primary PCI was not feasible, and that the best acute stage and 6 month outcome is achieved with performance of early coronary angiography and intervention within 3-17 hours after fibrinolysis. This conclusion was based upon evidence that the incidence major adverse cardiac events (MACE; deaths, congestive heart failure and cardiogenic shock, severe and life threatening bleeding) were lesser in (Group A) and (Group B) patients in whom early intervention (3-10 hours) and (10.1-17) after fibrinolysis was done respectively, this conclusion was supported by additional echocardiography parameters with highest median LVEF (Group A) patients followed by (Group B), meanwhile the MACE rates were highest and median LVEF was least in (Group C) in whom very late intervention (17.1-24 hours) was done after fibrinolysis. On the 6 months follow up there was survival, TLR and symptomatic HF benefit in (Groups A & B) compared to (Group C), regarding LVEF lowest median at (Group C) patients and similar median in (Groups A & B).

References

- Danchin N, Puymirat E, Steg PG, Goldstein P, Schiele F, et al. (2014) Five-Year Survival in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction According to Modalities of Reperfusion Therapy: The French Registry on Acute ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI) 2005 Cohort. Circulation 129(16): 1629-1636.

- Sinnaeve PR, Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, et al. (2014) STEMI Patients Randomized to a Pharmaco-Invasive Strategy or Primary PCI: The STREAM 1-Year Mortality Follow-Up. Circulation 130: 1139-1145

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, et al. (2018) 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST- segment elevation. Eur Heart J 39(2): 119-177.

- Madan M, Halvorsen S, Di Mario C, Tan M, Westerhout CM, et al. (2015) Relationship between time to invasive assessment and clinical outcomes of patients undergoing an early invasive strategy after fibrinolysis for ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: a patientlevel analysis of the randomized early routine invasive clinical trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 8(1 Pt B): 166-174.

- Capodanno D, Dangas G (2012) Facilitated/pharmaco-invasive approaches in STEMI. Curr Cardiol Rev 8(3): 177-180.

- Al Shammeri O, Garcia L (2013) Thrombolysis in the age of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Mini-Review and Meta-analysis of Early PCI. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 7(1): 91-100.