A Rare Case of Traumatic Leptomeningeal Cyst in Adult: Case Report

Aneesh KM1* and Shahana N2

1Specialist Radiologist, NMC Medical Center, UAE

2Specialist Radiologist, Amina Hospital, UAE

Submission: November 13, 2018; Published: November 26, 2018

*Corresponding author: Aneesh KM, Specialist Radiologist, NMC Medical Center, Sharjah, UAE.

How to cite this article: Aneesh KM, Shahana N. A Rare Case of Traumatic Leptomeningeal Cyst in Adult: Case Report. J Head Neck Spine Surg. 2018; 3(4): 555620. DOI: 10.19080/JHNSS.2018.03.555620

Abstract

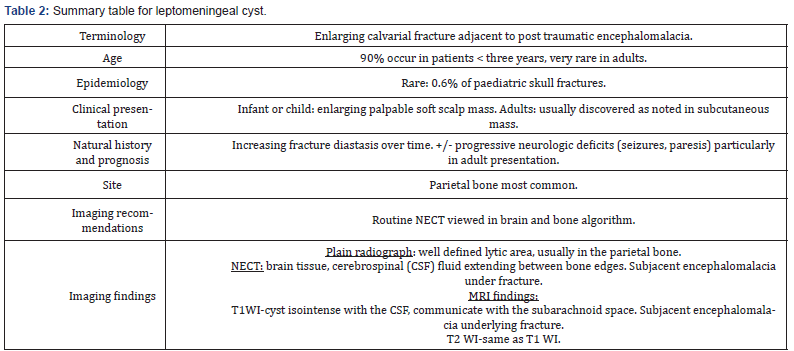

Traumatic leptomeningeal cysts are a rare complication of a childhood skull fracture. Clinical manifestations of a childhood trauma are very rare in adults and usually presents as a nontender subcutaneous mass with progressive neurological deficit and seizures.

Keywords: Leptomeningeal cyst; Adult; Trauma; Seizures; Skull fracture

Abbrevations: CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; T1WI: T1-Weighted Images; T2WI: T2-Weighted Images

Case Report

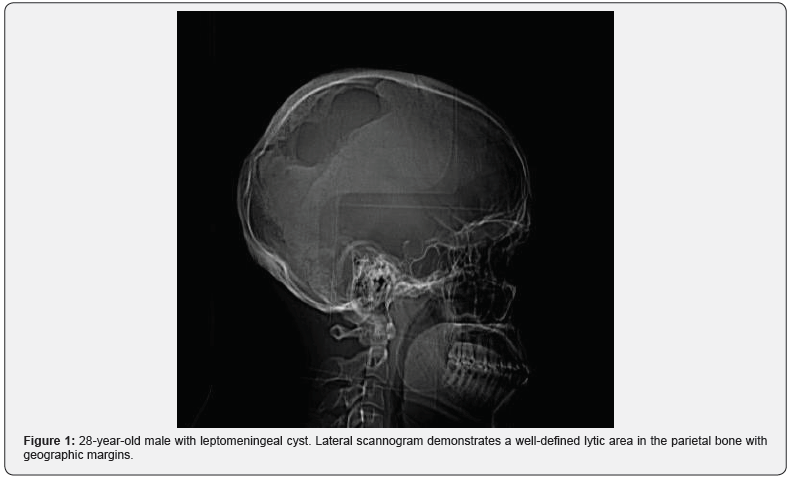

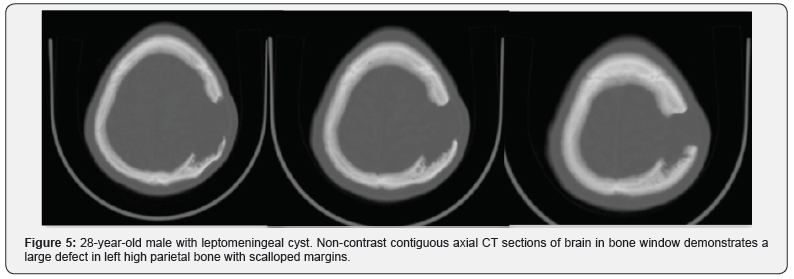

A 28-year-old male presenting with a gradually increasing scalp swelling in the left parietal region over a long period and seizures. The patient was conscious. On physical examination, there was a cystic swelling over the left parietal prominence. The swelling was compressible but non-tender and non-pulsatile. There was a history of head injury during infancy (Figure 1-5).

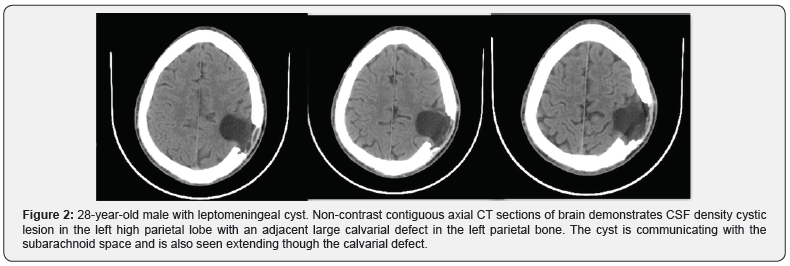

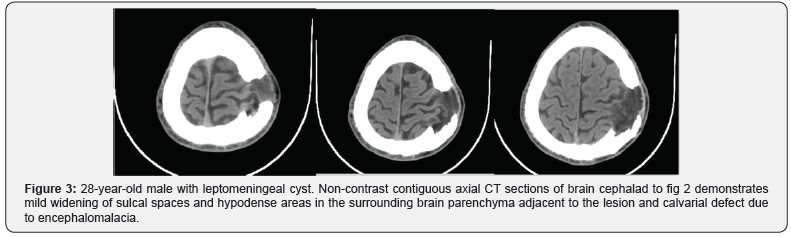

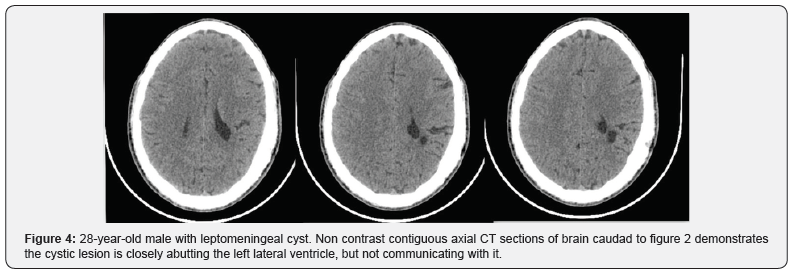

A non-contrast enhanced head computed tomography (CT) examination was performed on a multidetector CT (Lightspeed ultra, GE Medical Systems) and demonstrated a large calvarial defect in the left parietal region with irregular and beveled margins. An adjacent CSF density cystic lesion of size 42x41mm noted in the left high parietal lobe. The cyst was seen communicating with the subarachnoid space and also seen extending though the calvarial defect. Mild widening of sulcal spaces and hypodense areas also noted in the surrounding brain parenchyma due to encephalomalacia. The cystic lesion was seen closely abutting the left lateral ventricle with focal dilatation of the ventricle. But there was no communication of the cyst with the ventricle. Corrective surgery was done. The intraoperative and postoperative period was uneventful.

Discussion

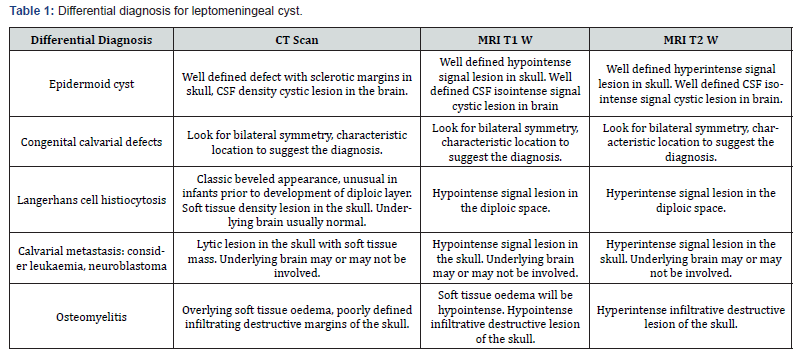

Growing skull fractures usually occur due to severe head trauma during the first three years of life, particularly in infancy. Incidence reported is only.05 to.1% of skull fracture in childhood [1,2]. Cause for growing skull fractures is multifactorial but the main factor is tear in the dura mater. The pulsatile force of CSF and pressure of growing brain will cause cerebral or subarachnoid herniation through the dural tear which causes the fracture in the thin skull to enlarge. This interposition of tissue prevents osteoblasts from migrating, inhibiting fracture healing. The resorption of the adjacent bone by the continuous pressure from tissue herniation through the bone gap adds to the progression of the fracture line (Tables 1-2).

Table abbreviations: CT = Computed Tomography, MRI = Magnetic Resonance Imaging, CSF = Cerebrospinal fluid, T1WI= T1-weighted images, T2WI= T2-weighted images.

Table abbreviations: CT = Computed Tomography, MRI = Magnetic Resonance Imaging, CSF = Cerebrospinal fluid, T1WI= T1-weighted images, T2WI= T2-weighted images.

The brain extrusion may be present shortly after diastatic linear fracture in neonates and young infants [3] resulting in focal dilatation of the lateral ventricle near the growing fracture. This focal dilatation may be seen in adults which is also seen in this case. This focal dilatation is reversible and may normalize after surgical repair [4]. Cranial defects never increase if the underlying dura is intact. Leptomeningeal cyst never occurs if the dura is intact.

Another risk factor is severity of underlying trauma. A linear fracture associated with hemorrhagic contusion of subjacent brain suggests a trauma significant enough to cause dural laceration. Cystic changes at the growing fracture site may be because of cystic encephalomalacia. Post traumatic aneurysms and subdural hematomas have also been reported to accompany growing skull fractures [6,7]. Though most patients show damage to underlying brain, this finding is not a prerequisite for the development of growing skull fractures [8].

These skull fractures after reaching maximum extent will cease to grow and remain stable throughout adulthood [2,5].

A depressed fracture usually does not become a growing fracture [9] but a linear fracture extending from a depressed one can become one [10].

A fracture with a diastasis of >4mm may be considered at risk of developing a growing skull fracture [3,11,12]. But a post traumatic diastasis of a cranial suture is an unusual site for a growing fracture. Growing fractures can even be seen in usually in linear fractures in thin areas of skull base associated with dural laceration, for e.g.: Orbital roof, ethmoid plate, frontal sinus.

These fractures commonly present as a progressive, scalp mass that appears sometime after head trauma sustained during infancy. There may seizures and hemiparesis, but an asymptomatic palpable mass may be the sole sign. The usual site is the parietal region. A growing fracture at the skull base may present with ocular proptosis or CSF rhinorrhea or otorrhea.

A plain radiograph may show a fracture line that crosses a coronal or lambdoid suture, but it is usually limited to a parietal bone [13]. CT or MRI demonstrates a cystic lesion near the fracture site communicating with the subarachnoid spaces and extending though the bony defect. Margins of bony defect may be beveled or irregular. Adjacent brain parenchyma usually shows mild encephalomalacia changes and focal atrophy. Gliosis may also see in the adjacent brain parenchyma. On CT scan gliosis is seen as hypodense areas. On MRI gliosis is seen as hypointense T1 and hyperintense T2 signals.

Because of neurological deterioration and of seizure disorder surgical correction of growing fractures is recommended.

Even though traumatic leptomeningeal cyst is rare in adults, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of intracranial cystic lesions with adjacent calvarial defects.

References

- Des champs GT, Blumenthal BI (1988) Radiologic seminar CCXLIX: Growing skull fractures of childhood. J Miss state Med Assoc 29(1): 16- 17.

- Ramamurthi B, Kalanaraman S (1970) Rationale for surgery in growing fractures of skull. J Neurosurg 32: 427-430.

- Thompson JB, Mason TH, Haines GL, Cassidy RJ (1973) Surgical management of diastatic linear fractures in infants. J Neurosurg 39(4): 493-497.

- Scarfo GB, Mariottini A, Tomaccini D, Palma L (1989) Growing skull fractures: progressive evolution of brain damage and effectiveness of surgical treatment. Childs Nerv Syst 5(3): 163-167.

- Rahimizadeh (1986) A growing skull fracture in the elderly. Neurosurgery 19: 675-676.

- Buckinghum MJ, Crone KR, Ball WS, Tomsick TA, Berger TS, et al. (1988) Traumatic intracranial aneurysms in childhood: Two cases and review of literature. Neurosurgery 22(2): 398-408.

- Locatelli D, Messina AL, Bonfanti N, et al. (1989) Growing fractures: an unusual complication of head injuries in paediatric patients. Neurehirurgia (stuttg) 32: 101-104.

- Lende RA, Erickson TC (1961) Growing skull fractures. J Neurosurg 18: 479-489.

- Arsenic C, Ciurea AV (1981) Clinicotherapeutic aspects in growing skull fractures. A review of literature. Childs Brain 8(3): 161-172.

- Lye RH, Occleshaw JV, Dutton J (1981) Growing fractures of skull and the role of CT. Case report. J Neurosurg 55: 470-472.

- Gruber FH (1969) Post traumatic leptomeningeal cysts. Am J Roentgenology 105(2): 305-307.

- Traveras JM, Ransohoff J (1953) Leptomeningeal cysts of brain following trauma with erosion of skull: a study of seven cases treated by surgery. Neurosurg 10(3): 233-243.

- Kingsley D, Till K, Hoase R (1978) Growing fractures of skull. J Neurosurg psychiatry 41(4): 312-318.