Extended External Auditory Canal Cholesteatoma: Case Report and Literature Review

Farias CHS, Bosaipo CS, Enout MR and Antunes ML*

Farias CHS, Bosaipo CS, Enout MR and Antunes ML*

Submission: June 02, 2018; Published: July 18, 2018

*Corresponding author: Marcos Luiz Antunes, Federal University of Sao Paulo (UNIFESP), R. Pedro de Toledo, 947 - Vila Mariana, São Paulo - SP, Brazil.

How to cite this article: Farias CHS, Bosaipo CS, Enout MR, Antunes ML. External Auditory Canal Cholesteatoma: Case Report and Literature Review. J Head Neck Spine Surg. 2018; 3(2): 555607. DOI: 10.19080/JHNSS.2018.03.555607

Abstract

Introduction: External auditory canal cholesteatoma (EACC) is a rare disease that manifests with unilateral insidious chronic pain and otorrhea. Its evolution is slow and not very symptomatic, and its diagnosis may be delayed. Hearing is usually preserved. Computed tomography (CT) is recommended for all patients. Treatment may be clinical or surgical.

Case report: Female, 69 years old, with complaint of hypoacusis and right otorrhea 10 months ago. Otoscopy of the right ear with epidermal debris in the external auditory canal and intact tympanic membrane. Tonal audiometry showed moderate right mixed loss. Temporal bone CT with expansive formation with soft tissue density with insinuation to the external auditory canal on the right. MRI with lesion presenting hypersignal at T2 and in the diffusion sequence, in close contact with the sigmoid sinus. The patient underwent open mastoidectomy. During the intraoperative period, facial nerve, sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb, posterior and middle fossa meningeal exposures were observed. Patient progressed well, without facial paralysis or recurrence of the disease.

Discussion:This work calls attention to a case of EACC with extensive invasion of the mastoid at the diagnosis. The diagnosis of the lesion was clinical. CT and MRI aided in the differential diagnosis. EACC, due to its insidious nature and anatomical correlation with noble structures, should always be remembered in the differential diagnosis of external auditory canal lesions.

Keywords: Cholesteatoma; External auditory canal; External auditory canal cholesteatoma

Introduction

Cholesteatoma is usually defined as the presence of skin in the middle ear cavity, that is, it consists of an external matrix formed by stratified keratinized squamous epithelium on a perimatrix of fibroconective tissue. It has lithic and migration characteristics and can cause erosion of adjacent bone structures. Traditionally, it is classified as congenital and acquired (primary and secondary), depending on its etiology [1].

External auditory canal cholesteatoma (EACC) presents uncertain etiology, representing an invasion of the squamous epithelium associated with erosion in a localized area of the external auditory canal (EAC). Several theories have been presented to try to explain the aetiology and pathogenesis of this disease: localized periostitis, chronic inflammation of the EAC, failed spontaneous elimination of desquamated epithelial cells and dehiscence of the petrotympanic fissure[2,3]. Smoking and small traumas in the ear canal may also predispose its onset [2] and there are described cases of EACC post-radiotherapy, probably due to tissue degradation with eventual radionecrosis, impairing normal collagen synthesis and cell production [4].

It is a rare disease, with an estimated incidence of 1.2: 1,000 new patients seen in otologicalpractice [5]. The first author to describe the manifestations of the EACC was Toynbee in 1850 [6]. It occurs mainly in the population over 40 years old and manifests with unilateral insidious chronic pain and otorrhea. In a review of 48 cases, otalgia was the predominant symptom and frequently related to extension to nearby structures [2].

Thus, the diagnosis is eminently clinical. When examining otoscopy, the tympanic membrane is intact in most cases with erosion restricted to one point of EAC [7]. Hearing is usually preserved.6 Since the evolution is slow and not very symptomatic, its diagnosis can be late, evolving with progressive bone destruction and involvement of important neighboring structures (lateral sinus, facial nerve, posterior fossa). Computed tomography (CT) is recommended for all patients, on suspicion of EACC [3,8].

The differential diagnosis of EACC is made with necrotizing external otitis, tumors and keratosis obliterans. Keratosis obliterans, unlike EACC, is more frequent in young adults with severe otalgia and bilateral conductive hearing loss, and the EAC is filled with a keratin plug which when removed reveals a narrow, hyperemic and granulating tissue. In EACC, the lesion usually presents as an epidermal diverticulum in the inferior wall of the canal, filled by epidermal debris and otorrhea, the rest of the EAC is normal [7].

The treatment of EACC can be clinical or surgical. The first is performed through local cleaning and topical antibiotic application. The second is based on the removal of cholesteatoma and necrotic bone. Most studies show that minor lesions can be treated conservatively or by minor procedures under local anesthesia, whereas larger lesions require a surgical procedure to remove the cholesteatoma [2]. The following surgical indications are considered: chronic pain (despite clinical treatment); constant infection (due to the possibility of developing bacterial resistance); the onset of facial paralysis or chronic vertigo; progression of the lesion during follow-up; CT showing involvement of the hypotympanum, jugular dome or mastoid; Diabetes Mellitus or immunosuppression (predisposition to necrotizing otitis externa) [7].

Case Report

Patient R.M.L.A., female, 69 years old, attended the Otorhinolaryngology outpatient clinic of the State Hospital of Diadema with complaint of hypoacusis and intermittent otorrhea on the right ten (10) months ago. She denied otalgia or dizziness. Otoscopy of the right ear showed an accumulation of epidermal debris in the external auditory canal, which when removed revealed an intact tympanic membrane. The left otoscopy was normal. Tonal audiometry showed moderate right mixed loss (Figure1).

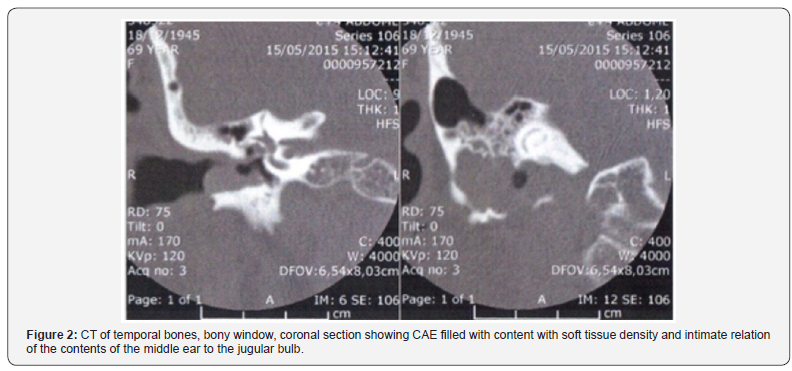

In the suspicion of cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal, CT was requested of temporal bones, evidencing an expansive formation with density of soft parts of inaccurate limits, in the posterolateral region of the right mastoid, widening the jugular foramen on this side, associated with component lithium bone, gaseous foci of permeation and cortical rupture of the anterior region of the mastoid, with an insinuation to the EAC on this side (Figure 2).

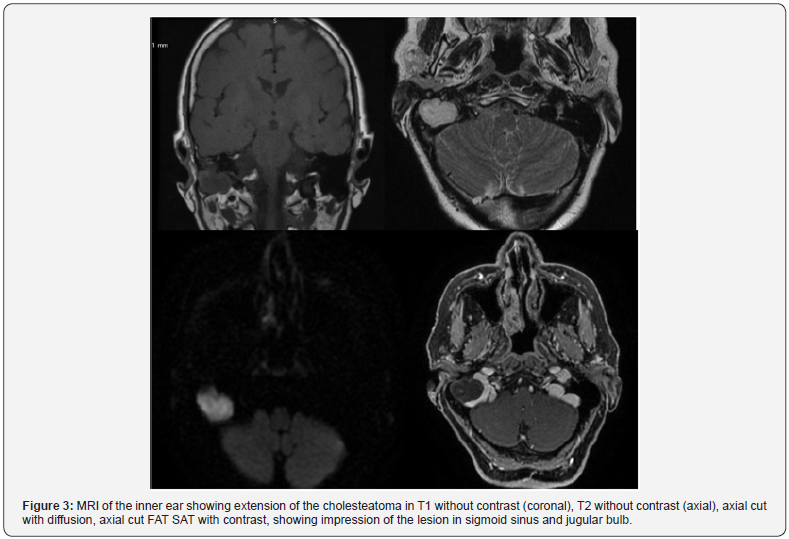

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used for differential diagnosis, which showed an expansive lesion in the posteroinferior portion of the right mastoid, with lobulated contours, which penetrated the jugular foramen and CAE on this side. The lesion presented hypersignal at T2 and in the diffusion sequence and discreet peripheral enhancement of its superlateral component. In addition, it had an intimate contact with the sigmoid sinus and determined the extrinsic impression of this sinus and the upper third of the right jugular vein (Figure 3).

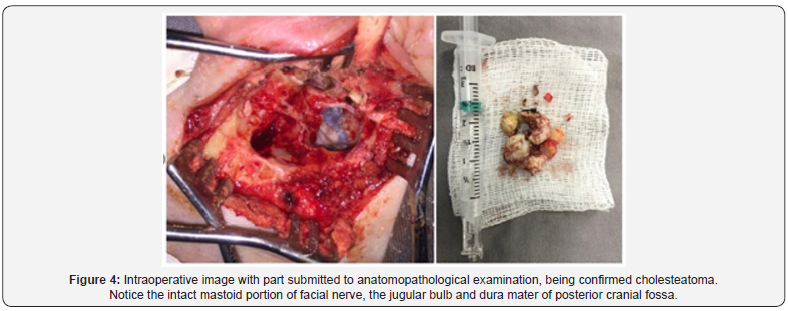

The patient underwent open mastoidectomy with preservation of the antrum due to the absence of disease in this region and as a way of avoiding a large cavity. In the intraoperative period, the exposure of the sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb and pre-sigmoid meningeal of the posterior fossa was observed. Identified facial nerve exposed from the rope branch of the eardrum to its exit at the tip of the mastoid, preserved without trauma (Figure 4).

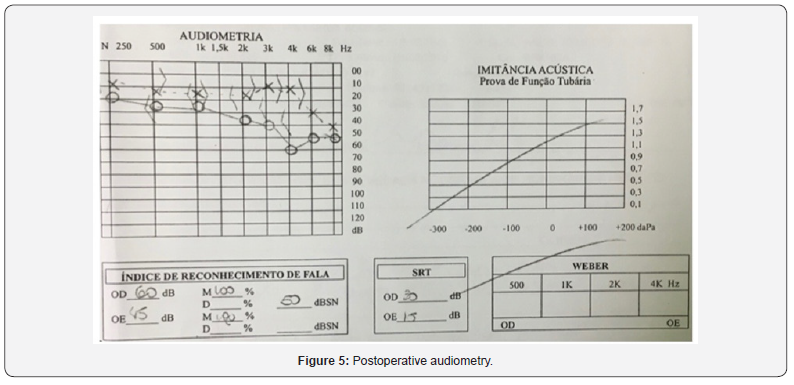

The patient progressed well, with no signs of peripheral facial paralysis, without auditory threshold worsening (Figure 5) and no recurrence in the 10-month postoperative period.

Discussion

The EACC is a rare condition that presents with insidious symptoms, while the extent of bone destruction progresses. In the presented case the lesion was extensive at the time of its diagnosis, compatible with the majority of cases in the literature, diagnosed late [2,7,9].

Considering that the etiology of secondary EACC can be explained, the origin of primary EACC remains uncertain. No etiologic factor was identified in this case, so it can be considered as idiopathic EACC.

Regarding the symptoms, the patient denied otalgia, different from the cases found in our review of the literature [2,7,9].

The surgical procedure was indicated by the appearance of the lesion and the patient’s lack of restrictions to perform it, and the open mastoidectomy was performed, obtaining success and ensuring a good control of the disease in the postoperative period.

The involvement of the facial nerve pathway and the presence of sigmoid sinus dehiscence and posterior fossa meninges could be the cause of intraoperative complication or postoperative sequela, however there were no intercurrences during the procedure. The patient also did not present auditory sequela due to the procedure.

As a form of postoperative follow-up of the lesion, in addition to adequate cavity control and attention to the patient’s symptoms, in the suspicion of residual cholesteatoma, it is possible to perform MRI with diffusion [10].

Conclusion

a) Although rare, attention should be paid to the diagnosis of EACC in cases of chronic otorrhea associated with otalgia without changes in the tympanic membrane.

b) All patients should undergo temporal bone CT scans to assess the extent of the injury as well as the involvement of adjacent structures.

c) Surgical treatment in most cases is the indicated and has shown good results in the removal and control of the disease.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank to all people involved & who supported this study.

References

- Ribeiro FAQ, Pereira CSB (2011) Cholesteatomatous otitis media. Otorhinolaryngology. (2ndedn), Sao Paulo, Brazil, pp.93-102.

- Owen HH, Rosborg J, Gaihede M (2006) Cholesteatoma of the external ear canal: etiological factors, symptoms and clinical findings in a series of 48 cases. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 6: 16.

- Omezzine SJ, et al. (2013) Spontaneous cholesteatoma of the external auditory channel: The utility of CT. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 94: 438-442.

- Sapmaz E, Somuk BT, Soyalıç H, Koçak C, Gökçe E (2016) Postradiotherapy bilateral external auditory cholesteatoma channel. Kulak BurunBogazIhtisDerg (The Turkish Journal of Ear Nose and Throat) 26(1): 60-63.

- Anthony PF, Anthony WP (1982) Surgical treatment of external auditory cholesteatoma channel. Laryngoscope 92(1): 70-75.

- Toynbee J (1850) A specimen of molluscum contagiosum developed in the external auditory meatus. Lond Med Gaz 46: 261-264.

- Zanini FD, Ameno ES, Magaldi SO, Lamar RA (2005) Cholesteatoma of external auditory canal: a case report. Rev Bras Otorhinolaringolol 71(1): 91-93.

- Malcom PN, Francis IS, Wareing MJ, Cox TC (1997) CT Appearances of external ear channel cholesteatoma. Br J Radiol 70(837): 959-960.

- Rabbit LB, Delegate RM, Finamore CMJM, Rodrigues J, Secchi MMD (2000) Cholesteatoma of External Auditory Channel. Rev Bras de Otorrinolaringol 66(3): 285-288.

- Aarts MC, Rovers MM, van der Veen EL, Schilder AG, van der Heijden GJ, et al. (2010) The diagnostic value of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in detecting residual cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143(1): 12-16.