Effects of Trypanosomosis on Hemogram and Some Biochemical Parameters of Guinea Pigs Experimentally Infected with Trypanosome Brucei Brucei in Maiduguri, Nigeria

Abdullahi AM1, Iliyasu D2 Galadima HB3, Ibrahim UI4, Mbaya AW5 and Wiam I6

1Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine University of Maiduguri, Nigeria

2Department of Theriogenology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Maiduguri, Nigeria

3Department of Animal Health and Production, College of Agriculture, Nigeria

4Department of veterinary medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine University of Maiduguri, Nigeria

5Department of Veterinary Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Maiduguri, Nigeria

6Department of Veterinary Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine University of Maiduguri, Nigeria

Submission: October 31, 2018;Published: November 30, 2018

*Corresponding author: Abdullahi AM, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine University of Maiduguri, Nigeria.

How to cite this article: Abdullahi A, Iliyasu D, Galadima H, Ibrahim U, Mbaya A etc al. Effects of Trypanosomosis on Hemogram and Some Biochemical Parameters of Guinea Pigs Experimentally Infected with Trypanosome Brucei Brucei in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Dairy and Vet Sci J. 2018; 8(3): 555737. DOI: 10.19080/JDVS.2018.08.555737

Abstract

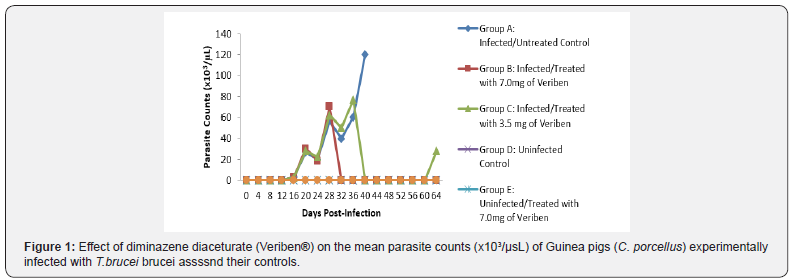

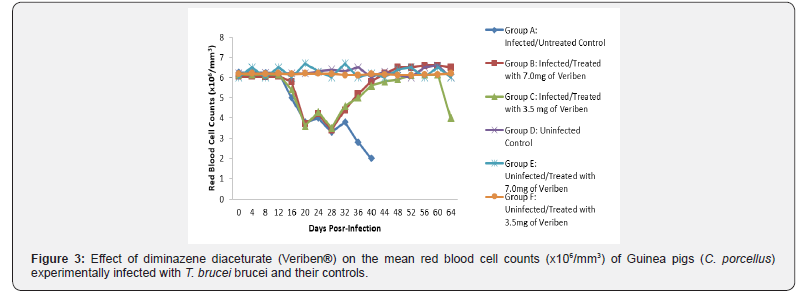

The study was designed to evaluate the effect of tryponosomosis on Hemogram and some biochemical parameters of guinea pigs. Guinea pigs of both sexes weighing (5-10kg) were divided into six groups (A, B, C, D, E and F) with five guinea pigs in each group. At day zero, to establish the baseline data, all the animals in each of the six groups were bled for haematology and serum biochemistry and clinical parameters (rectal temperature, respiratory rate, pulse rate and heart beats) were recorded while general body condition and physical signs were also evaluated. Groups A, B and C were intraperitoneally (IP) inoculated with 1×106 dose of Trypanosoma brucei brucei contained in 0.5 ml of blood. Thereafter, blood samples were collected every other four (4) days for evaluation of haematology and serum electrolytes through the experimental period. Group D, E and F was uninfected control. All the infected groups (A, B, and C) had a pre-patent period of 16 days with similar levels of parasitaemia of 45.7±3.38 across the groups. The observed clinical signs among the infected groups (A, B and C) were pyrexia, pale feet, snout, pinnae and mucous membrane, anaemia, dullness, emaciation and loss of weight. In group A, a mean parasitaemia of 2.8 ± 0.84 occurred by day 16 post-infection post infection which continued to rise significantly without abating (p<0.05) to a peak count of 120.2 ± 5.48 by day 40 post infection. Similar findings were noticed across the groups. In groups D, E and F, their respective pre-infection RBC values of 6.20 ± 1.24, 6.24 ± 1.24 and 6.18 ± 1.24 remained constant (p>0.05).

Abbreviations: IP: Intraperitoneally; LN: Liquid Nitrogen; NITOR: Nigerian Institute of Trypanosome and Onchocerciasis; SD: Standard Deviation; PBSG: Phosphate Buffered Saline Glucose;

Introduction

Trypanosomosis is one of the most important zoonotic disease commonly found in Africa regions and South America [1]. African trypanosomosis is caused by a protozoan parasite belonging to the genus Trypanosoma and is transmitted by tsetse flies to the final host. The disease is characterized by high morbidity and mortality of infected livestock. Animal trypanosomosis has been estimated to cost Africa about US$ 4.5 billion per year [2]. Trypanosomosis affect almost all vertebrates particularly man and livestock. But wild animals such as Bovidae and suidae, act as asymptomatic carriers [3]. Biological transmission (cyclic) of these parasites by tsetse fly (Glossina), is rampart in tsetse belt zone of Nigeria [3,4]. While arthropod vectors, haematophagus, of the family Tabanidae, Hippoboscidae, Stomoxynae Haematopota, lyperosia, and Chrysops species are responsible for the mechanical transmission of the parasite in the tropics [5,6]. Tsetse flies are efficient transmitters of trypanosomes especially Trypanosoma vivax which develop in their mouth [7]. Transplacental transmission of trypanosomes has been reported in cattle [8]. Trypanosoma vivax, T. congolense and T. brucei have been reported to cause Nagana in cattle, while T. evansi caused surra in camels (Camelus dromedarieus) [9].

Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. brucei rhodeseinse are responsible for human sleeping sickness in east and west Africa countries respectively, while T. cruzi transmitted by triatomid bugs (Triatonia Magista) is responsible for causing chagas disease in humans in south America [10]. The trypanosomes group of T. brucei (T. brucei, T. b. gambiense, T. b. rhodensiense and T. evansi) are more of tissue invading (humoral) parasites whereas, T. congolense, T. vivax and T. cruzi are restricted as hemoparasites (blood circulation parasites) or (haemic) [11,12]. Animal trypanosomosis is lethal if left untreated. It causes severe losses in livestock industries as a result of poor growth, weight loss, and low milk yield, poor capacity to work, infertility and abortion have been reported in low levels of infection [3]. Control of the disease therefore is significant through hematological and biochemical evaluation that can lead to a reliable diagnosis that can guarantee optimistic treatment that will restore production in endemic areas and boost livestock production industries.

Materials and Methods

Source of Trypanosoma Brucei Brucei

The trypanosoma parasites used for the study was “Federe” strain of Trypanosoma brucei brucei, which was obtained from NITOR (Nigerian Institute of Trypanosome and Onchocerciasis) Kaduna State. Nigeria. The organism was isolated from an outbreak of bovine trypanosomosis in Nassarawa State of Nigeria. It was identified based on its morphology and negative blood inhibition and infectivity test and was stabilized by four passage in rats before storage in liquid nitrogen (LN). Four donor rats were used to multiply the parasites and transported by road from Kaduna to the Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. The parasites were then maintained in Albino rats by serial passage until used.

Experimental Animals

Total of Thirty (30) apparently healthy Guinea pigs of both sexes and of different ages were used in the study. The animals were purchased from breeders in Plateau State. On arrival, they were kept in clean and well-ventilated cages in the Large Animal Veterinary Clinic, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, university of Maiduguri, Nigeria. They were routinely screened for ecto, haemo and endo parasites using standard methods. The Guinea pigs were housed in a suitable locally made wire mesh cages with sawdust as bedding, fed with varieties of vegetables and commercial growers feed (Vital Feeds, PLC, Nigeria), and water provided ad libitum. They could acclimatize to laboratory condition for two weeks prior to commencement of the experiment. The experimental procedure was in accordance with regulations of the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Maiduguri.

Experimental Infection

Four (4) adult albino rats were used as donors of T. brucei brucei, the rats were purchased from NITOR, Kaduna State. They were screened for internal and external parasites using standard method as described by [5]. They were inoculated intra peritoneally with 0.5 ml of T. brucei brucei parasiteamic blood with multiple parasites. At 4 days post inoculation, parasiteamia was established and became obvious. The donor rats were bled via the tail vein into a petri dish, the blood was diluted with phosphate buffered saline glucose (PBSG) (pH 7.4). Each Guinea pig in groups A, B and C were inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.5ml of blood containing 1.0 × 106 Trypanosoma brucei brucei as quantified using serial dilution as reported by Herbert & Lumsden [13].

Experimental Design

Thirty Guinea pigs were randomly divided into six groups with five Guinea pigs in group (A, B, C, D, E and F). At day zero, all the animals were bled for haematology and serum biochemistry to establish a baseline data. Thereafter, physical condition and clinical parameters of all the animals were evaluated (rectal temperature, respiratory rate, pulse rate and heart beats) and body weights respectively. Groups A, B and C were inoculated with 0.5ml of blood containing 1.0 × 106 Trypanosoma brucei brucei intraperitoneally (IP). Blood sample were collected for haematology and serum electrolytes profiles at interval of 4 days from day zero until the end of the experiment. Group A was infected with 0.5 ml of blood containing 1.0 × 106 Trypanosoma brucei brucei (untreated control), Group B was infected with 0.5ml of blood containing 1.0 × 106 Trypanosoma brucei brucei (treated with Diaminazene diaceturate Veriben®) at day 28 post infection (p.i) at the dose rate of 7.0 mg/kg body weight. Group C was infected with 0.5ml of blood containing 1.0 × 106 Trypanosoma brucei brucei (treated with Diaminazene diaceturate (Veriben®) at day 28 post infection at the dose rate of 3.5mg/kg body weight. While Group D and Group E were uninfected/untreated (control) and uninfected treated with diaminazene diaceturate (Verben®) at day 28 (p.i) at the dose rate of 7.0mg/kg body weight respectively. Group F was uninfected (treated with diaminazene diaceturate (Veriben®) at day 28 post infection at the dose rate of 3.5mg/kg body weight.

Post Infection Evaluation of Guinea pigs

All the Guinea pigs were observed daily for the manifestation of clinical signs of trypanosomosis, which include morbidity and mortality. Meanwhile, detection of parasitaemia was done every 4 days post day zero and the degree of parasitaemia was projected by the rapid matching technique as described by [13,14].

Blood Collection

Blood for haematological and serum electrolytes examination were aseptically collected at 4 days interval preliminary from day 0 to day 64 post infection. The Guinea pigs were bled using 2ml syringe through cardiac puncture 0.5ml and 1ml of the blood was transferred into tubes containing anticoagulants (EDTA) and plain for hematological indices and sera for biochemical profiles respectively. Hematological and biochemical parameters were determine as described Henry & Tietz [15].

Statistical Analysis

Data generated were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) using Two-way analysis of variance was used to compare the data between groups and value p < 0.05 was considered significant [16].

Results

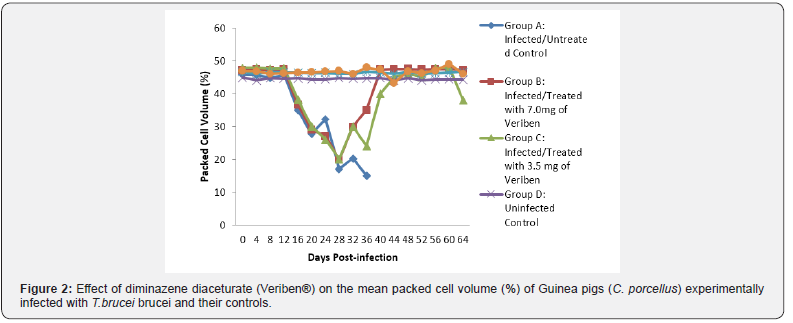

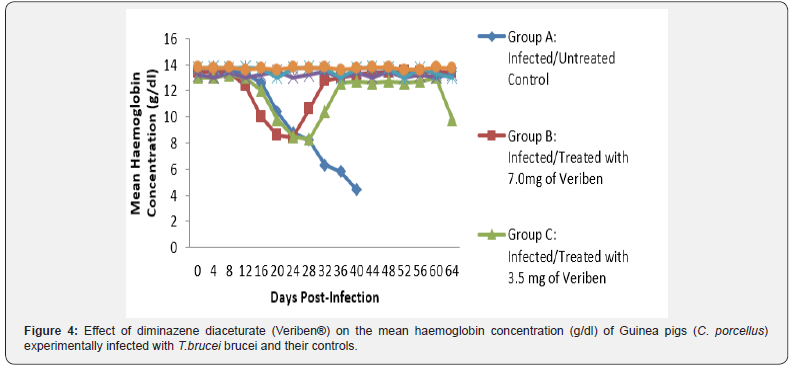

The prepatent period in both groups was the same form 4 - 8 days post infection. Following patency, parasitaemia fluctuated considerably in both groups with a higher recorded and least in group A and B respectively as presented in Figure 1. There was a significant decrease in PCV values of both infected groups compared with their controls (Figure 2). The decline in PCV values began with the arrival of trypanosomes in circulation of all the infected groups with different degrees of anaemia as shown in (Figure 2). The value of RBC declined significantly (p<0.05) in all the infected groups following parasitaemia without reduction up to day 40 post infection in group A as presented in (Figure 3). Group A, Hb value significantly decreased following parasitaemia hence, the Hb value continued to decline significantly (p<0.05) without abating up to day 40 post infection as documented in (Figure 4).

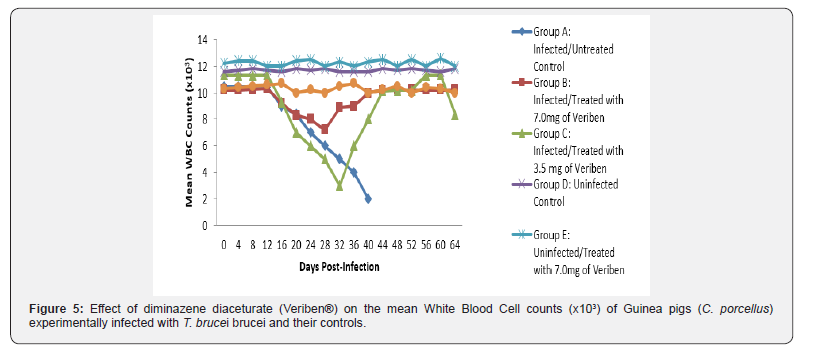

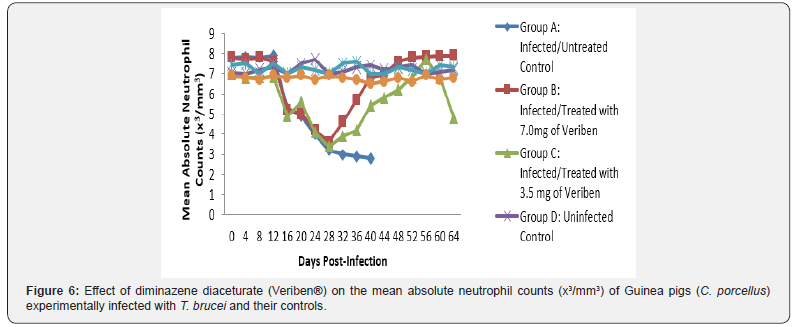

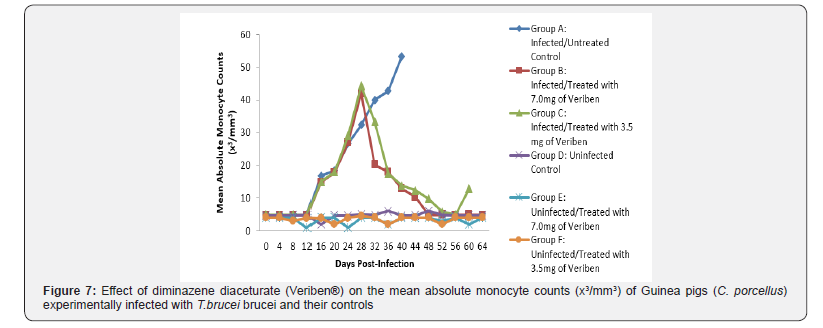

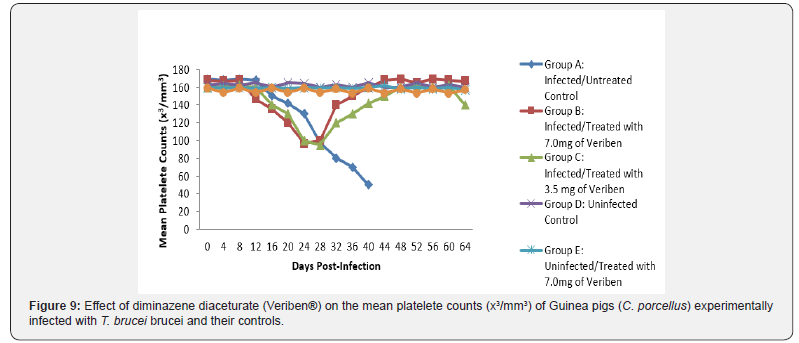

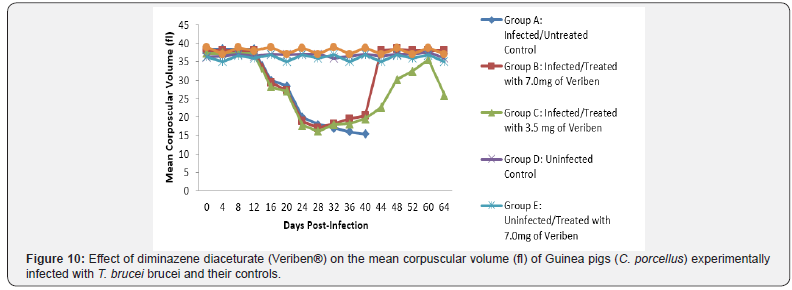

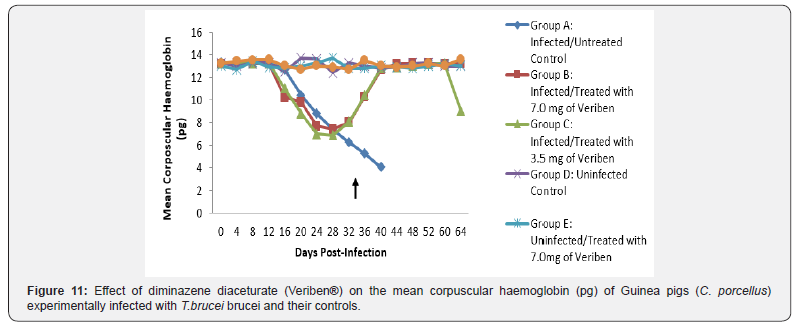

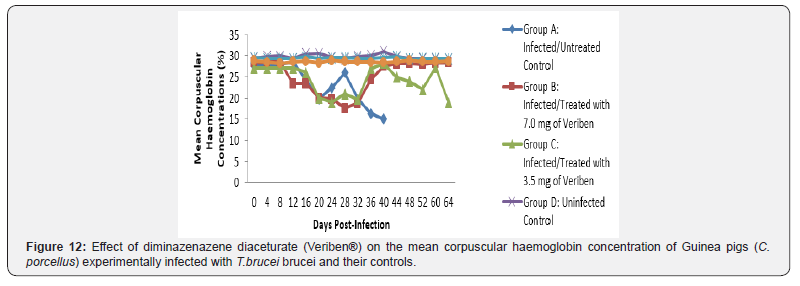

From day 16 (pi) when parasitaemia became patent in all the infected groups, the WBC value continuous to declined significantly particularly prominent in group A and B as shown in (Figure 5). The differential leucocytes count of all the infected groups declined following the establishment of parasitaemia by day 16 post infection, hence the value continue to decline significantly (p<0.05) in group A, B and C as indicated in (Figures 6-8). While there was significant decreased in platelets count in all the infected groups following parasitaemia appearance in day 16 post infection in group A and B as shown in (Figure 9) In group A, the values of MCV decreased significantly (p<0.05) following establishment of parasitaemia by day 16 post infection similar findings was observed on the mean corpuscular haemoglobin MCH of the Guinea pigs (C. porcellus) as presented in (Figures 10- 12).

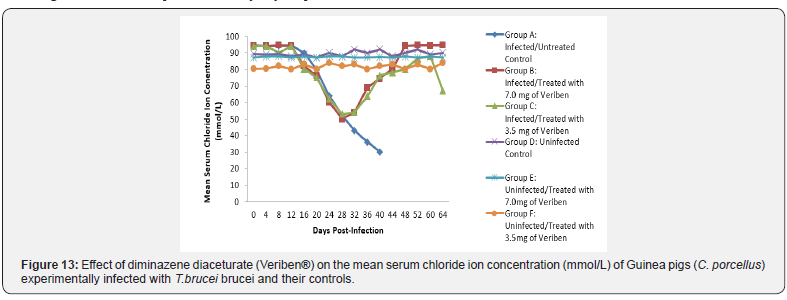

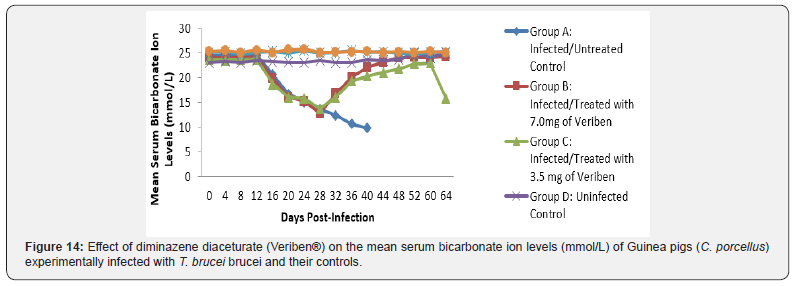

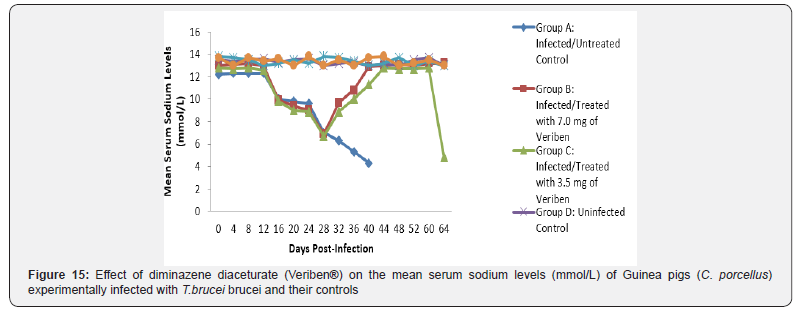

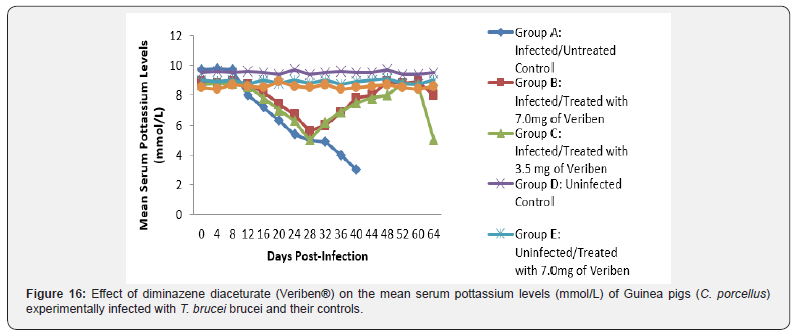

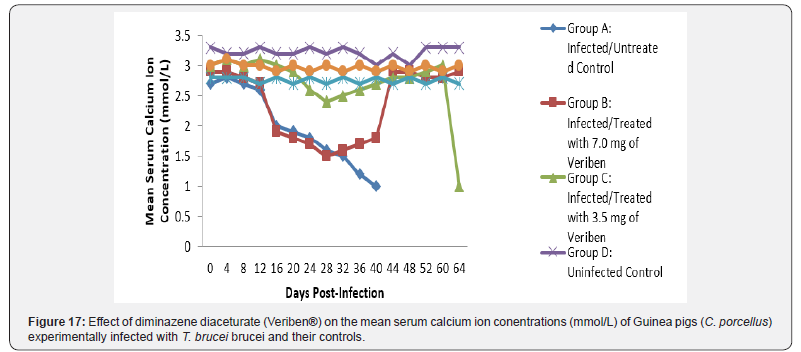

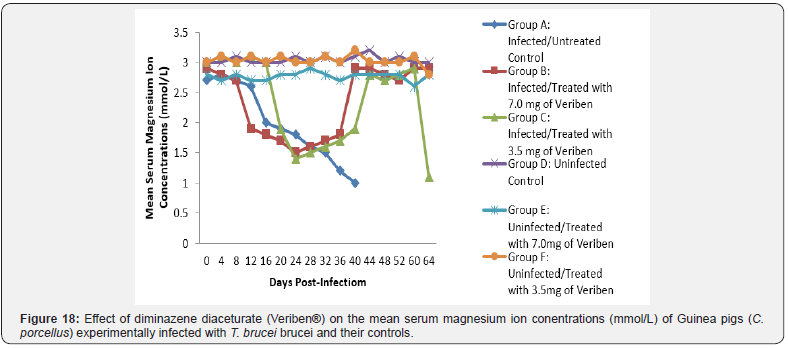

The mean chloride ion concentrations of the Guinea pigs (C. porcellus) continually decreased following establishment of parasitaemia by day 16 post infection in all the treated groups at different days, similar findings was noticed on the mean bicarbonate ion concentrations of the Guinea pigs (C. porcellus) at day 16 post infection and mean serum sodium levels of Guinea pigs (C. porcellus) the serum sodium levels decreased significantly following establishment of parasitaemia by day 16 post infection in all the treated groups as show in (Figures 13-15). The mean serum calcium ion concentration, mean serum potassium levels and magnesium ion concentration of Guinea pigs (C.porcellus) experimentally infected with T.brucei brucei were continually decreased following establishment of parasitaemia by day 16 post infection in all the treated groups at different days interval as presented in (Figures 16-18).

Discussion

The main clinical signs observed following experimental infection were respiratory distress, anemia, raised hair coat, dullness, anorexia and emaciation, this agreed with findings of several author reported in several species of laboratory animals and livestock. After the manifestation of clinical signs, the infected Guinea pigs shows parasitaemia by day 16 post infection. This is contrary to the findings of Umar [17] who observed a prepatent period of 4 days in rats infected with Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Infected Guinea pigs, started losing weight two weeks post infection. This may be associated with anorexia observed earlier, this was like the findings reported by [18,19] in rats infected with T. brucei brucei and rats infected with T. brucei gambiense respectively [20] also reported similar findings in rabbits infected with T. brucei brucei [21].

Despite the sudden changed in red cell parameters by decreased values of (PCV, RBC, Hb) during bouts of parasitaemia but gradually increased during the period of low and no parasitaemia. This tallies with the report of Yusuf [22], who observed a significant decrease in PCV, Hb, RBC and platelet count in rats infected with T. b. brucei. This showed an inverse relationship between parasitaemia and anaemia in most of the infected animals [23,24]. Anaemia is a consistent feature of trypanosome infections associated by oxidative stress that inflict damage to erythrocytes membrane and associate components. Equally, reactive oxygen radicals generated during trypanosomosis can attack erythrocyte membranes, which may induce oxidative stress that can trigger haemolysis [25]. It was also observed in the current study that only the group of Guinea pigs infected with T. b. brucei and treated with 3.5mg/kg diaminazene diaceturate (Veriben®) developed relapse parasitaemia at day 36 post treatment. Relapse in trypanosomosis has been linked to the parasites moving into areas of the body that are not accessible to the drugs like the brain. If infection can continue for some time before treatment then it is extremely difficult to obtain a permanent cure [26,27]. Also, Waitumbi [26] reported relapse parasitaemia in rabbit infected with T.brucei brucei following treatment with 25mg/kg of diaminazene diaceturate. The difference with the current study in the occurred relapse might be attributed to difference species of animal used and the drug dosage.

The haematological results of the present study agreed with earlier studies reported by [28-30]. The low PCV observed in the infected group may be linked to acute hemolysis that occur due to the progressive nature of the infection. Previous studies have shown that infection with trypanosomes resulted in increased susceptibility of red blood cell membrane to oxidative damage probably due to depletion or reduction of glutathione on the surface of the red blood cell [31]. Severity of anaemia has been related to reflect the intensity and length of parasitaemia. Several reports [32,33] have also ascribed acute anaemia in trypanosomosis to proliferating parasites. The low leucocytes (WBC, lymphocytes, and neutrophils) and platelet counts observed in the infected group may be attributed to the immunosuppressive actions of trypanosome infection [34].

The major function of platelets is to activate blood clotting mechanism and prevent loss of blood. In this study, the low platelet count observed in the infected untreated groups may indicate destruction of platelets by toxic products emanating from the trypanosomes [35]. Low platelet counts may also be attributed to other factors like pooling of blood into the spleen, removal of platelets by mononuclear phagocytic system and increased consumption of platelets by disseminated intravascular coagulation reaction in trypanosome infection [36]. However, leukocytosis, lymphopaenia and neutrophilia reported, may be due to trypanosomosis and these conditions usually occur as a result of wear and tear syndrome associated with animal immune system caused by the ever changing in variable surface glycoprotein of the infecting trypanosomes. The lymphopaenia encountered among the infected Guinea pigs may probably be due to an increased demand on the system for lymphocytes, which is a common requirement in both immune and inflammatory responses in trypanosomosis [37]. Inefficient recovery of iron from phagocytized RBCs is known to cause iron deficiency in the body. Igbokwe & Mbaya [38] reported that dyserythropoiesis is associated with animal trypanosomosis, and this may be attributed to the decreased MCV that was observed in the present study among the infected untreated groups.

The T. brucei brucei infected Guinea pigs were observed to be associated with marked reduction in serum sodium and chloride ion levels, and this might have been due to renal tubular damage of the kidneys. The decreased level of serum potassium observed in the current study was probably due to dehydration associated with tissue hypoxia. Reduction in bicarbonate ion (HCO3-) levels may be probably due to acidosis. The reduction may also be due to decreased alveolar ventilation and tissues hypoxia similar findings was reported by [39] in sheep infected by trypanosome.

The low bicarbonate levels can also be attributed to the massive leakages of some electrolytes from cells and tissues damage. However, the intermittent increase, low level and subsequent return of these electrolytes to pre-infection levels suggest the efficacy of the therapies, otherwise it might be as a result of massive cell and tissue damage at the terminal phase of this single infection. The decrease in the levels of calcium that was observed in this study agrees with the findings reported in cattle infected with T. congolense [40] and sheep infected with T. brucei brucei. This is said to be due to the deficiency in the parathyroid hormone because of the destruction of the parathyroid glands or a decrease in serum carriers, which in this case happens to be albumin. The drop in the level of serum magnesium concentration noted among the T. brucei brucei infected Guinea pigs observed in this study does not tally with the findings of Sow [41] among donkeys in Burkina Faso and that of Chaudhary & Iqbal [42] among camels in Pakistan. This may be as a result of the difference in the species of animals used. The drop-in magnesium concentration in blood observed in this study might be due to lowered dietary intake due to the infections. Biochemical evaluation of the body fluids gives an indication of the functional state of the various body organs and biochemical changes in body fluids that result from infections depend on the species of the parasite and its virulence [43].

Conclusion

It is clearly understood that high dose of Veriben® administered at the dose rate of 7.0mg/kg and 3.5mg/kg have the abilities of curbing the state of anaemia, immunosuppression, and serum electrolytes levels in trypanosome-infected guinea pigs placed on a dose dependent manner.

References

- Swallow BM (2000) Impacts of trypanosomosis in African agriculture, Programme against African Trypanosomosis Technical and Scientific series. Food Agriculture Organization (FAO) 2: 45-46.

- Codjia V, Mulatu W, Majiwa PAO, Leak SGA, Rowlands GJ, et al. (1993) Southwest Ethiopia Part 3. Occurrence of populations of T. congolense resistant to diminazene, isometamidium and homidium. Acta Tropica, 53: 151-163.

- Taylor MA, Coop RL, Wall RL (2007) Veterinary Parasitology. (3rd edn), Blackwell Publishing, USA.

- Itty P (1992) Economics of village cattle production in tsetse affected areas of Africa. A study of trypanosomosis control using trypanotorelant cattle and chemotherapy in Ethiopia, Kenya, Cote De Ivory, The Gambia, Zaire And Togo, Hurtong, Correvertag, Iconstanz (Germany).

- Soulsby EJL (1982) Helminthes, Arthropods and Protozoa parasites of domesticated Animals. Bailere Tindal, ISBN 0702008206 9780702008207, London, UK.

- Ngulde SI, Tijjani MB, Ihopo JM, Yauba AM (2013) Antitrypanasomal potency of methanol extract of cassia arereh delile root back in albino rats. International journal of Drug Research and technology 3: 1-7.

- Kettle DS (1995) Medical and Veterinary entomology. (2nd edn), CADI, Wallingford, pp. 225-227.

- Ogwu D, Njoku CO, Ogbogu VC (1992) Adrenal and thyroid dysfunction in experimental Trypanosoma congolense infection in cattle. Veterinary Parasitology 42: 15-26.

- Mbaya AW, Ibrahim UI, Apagu ST (2010) Trypanosomosis of the dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius) and its vectors in the tsetsefree arid zone of northeastern, Nigeria. Nigerian Veterinary Journal 31(3): 195-200.

- Solano P, Dela, Roqoes S, Duvalet G (2003) Biodiversity of trypanosomes pathogenic for cattle and their epidemiological importance. Annals of Society 68: 169-171.

- Igbokwe IO (1994) Mechanisms of cellular injury in African trypanosomiasis. Veterinary Bulletin 64(7): 611-620.

- Mbaya AW, Ibrahim UI (2011) In-vivo and in-vitro activities of medicinal plants on haemic and humoral trypanosomes: A review. International Journal of Pharmacology, 7(1): 1- 11.

- Herbert WJ, Lumsden WHR (1976) Tryponosoma brucei: A rapid matching method for estimating the host’s parasitaemia. Journal of Experimental Parasitology 40: 427-432.

- Henry R, Cannon DC, Winkelman JW (1974) Clinical Chemistry: Principle and Technics. Hagerstown, M. D Harper and Row London, UK, pp. 543.

- Tietz NW (1994) Serum albumin determination. Fundamentals of clinical chemistry with clinical Correlation. Balliere Tindall, London, UK, pp.2334.

- Graph Pad Instat (2009) Graph Pad Instat® vertion 3: 10, bit for windows, Gaph pad software, San Diengo, Calfonia, USA.

- Umar IA, Ogenyi E, Okodaso D, Kimeng E, Stancheva GI, et al. (2007) Amelioration of anaemia and organ damage by combined intraperitoneal administration of vitamins A and C to Trypanosoma brucei brucei -infected rats. African Journal of Biotechnology 6: 2083- 2086.

- Kristensson K, Claustrat B, Mhlanga, JDM, Moller M (1998) African trypanosomiasis in the rat alters melatonin secretion and melatonin receptor binding in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Research Bulletin 47: 265-269.

- Nyakundi JN, Crawley B, Smith RA, Pentreath VW (2002) The relationships between intestinal damage and circulating endotoxins in experimental Trypanosoma brucei brucei infections. Parasitology 124: 589-595.

- Nishimura K, Araki N, Ohnishi Y, Kozaki S (2001) Effects of dietary polyamine deficiency on Trypanosoma gambiense infection in rats. Experimental Parasitology, 97: 95-101.

- Toth LA, Tolley EA, Broady R, Blakely B, Krueger JM (1994) Sleep during experimental trypanosomiasis in rabbits. Proceedings of Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 205: 174-181.

- Yusuf OS, Oseni BS, Olayanju AO, Hassan MA, Ademosun AA, et al. (2013) Acute and Chronic Effects of Trypanosoma Brucei Brucei Experimental Infection on Bone Marrow and Peripheral Blood Cells in Wistar Rats. Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences 1(6): 1036-1040.

- Nwosu CO, Ikeme MM (1992) Parasitaemia and clinical manifestations in Trypanosoma brucei brucei infected dogs. Revenue d’Elevage: et de Medicine Veterinaire des pays Tropicaux 45: 273-277.

- Mbaya AW, Aliyu MM, Nwosu CO, Egbe-Nwiyi TNC (2009c) The relationship between parasitaemia and anaemia in a concurrent Trypanosoma brucei and haemonchus contortus infection in red fronted gazelles (Gazella rufifrons). Veterinarski Arhive 76(5): 451- 460.

- Ngure RM, Ongeri B, Karori MS, Wachira W, Maathai RG, et al. (2009) Anti-trypanosomal effects of Azadiracta Indica (neen) extract on trypanosomes Brucei rhodesiense Injected Mice. Eastern Journal of Medicine 14: 2-9.

- Waitumbi JN, Brown HC, Jennings FW, Holmes PH (1988) The relapse of Trypanosoma brucei brucei infections after chemotherapy in rabbits. Acta Tropica 45(1): 45-54.

- Mbaya AW, Kumshe HA, Nwosu CO, Onyeyili PA (2007) Toxicity and antytrypanosomal effect of Butyrospermum paradoxum (Sapotaceae) stem bark in rats infected with Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma congolense. Journal of Ethnopharmacoloy 111: 526-530.

- Anosa, VO (1988) Haematological and biochemical changes in human and animal trypanosomosis II. Revue d’élevage et de médecine vétérinaire des pays tropicaux, 41(1): 65-78.

- Igbokwe IO, Umar IA, Omage JJ, Ibrahim NDG, Kadima KB, et al. (1996) Effect of acute Trypanosoma vivax infection on cattle erythrocyte glutathione and susceptibility to in vitro peroxidation. Veterinary Parasitology 63: 215-224.

- Ekanem JT, Yusuf OK (2008) Some biochemical and haematological effects of black seed (Nigella sativa) oil on T. brucei-infected rats. African Journal of Biomedical Research 11: 79-85.

- Taiwo VO, Olaniyi MO, Ogunsanmi AO (2003) Comparative plasma biochemical changes and susceptibility of erythrocytes to in vitro peroxidation during experimental Trypanosome congolense and T brucei infections in sheep. Israel Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 58: 4.

- Ogunsanmi AO, Taiwo VO (2001) Pathobiochemical mechanisms involved in the control of the disease caused by Trypanosoma congolense in African grey duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia). Veterinary Parasitology 96: 51–63.

- Ekanem JT, Kolawole OM, Abbah OC (2008) Trypanocidal potential of methanolic extract of Bridelia ferruginea benth bark in Rattus novergicus. African Journal of Biochemistry Research 2(2): 045-050.

- Abubakar A, Iliyasu B, Yusuf AB, Igweh AC, Onyekwelu NA (2005) Antitrypanosomal and haematological effects of selected Nigerian medicinal plants in Wistar rats. Biokemistri 17: 95-99.

- Dow RB (1994) The clinical and laboratory utility of platelet volume parameters. Australian journal of Medical Science 15: 1-8.

- Kagira JM, Thuita JK, Ngotho M, Mdachi R, Mwangangi DM (2006) Haematology of experimental Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense infection in vervet monkeys. African Journal of Health Sciences 13: 59- 65

- Igbokwe IO, Nwosu CO (1997) Lack of correlation of anaemia with splenomegaly and hepatomegaly in Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma congolense infections of rats. Journal of Complex Pathology 117: 261-265.

- Mbaya AW, Kumshe HA,Nwosu CO (2012) The mechanism of anaemia in Trypanosomosis (D.S. Silverberg Ed.), In Tech. Publishers, Croatia pp. 240-282.

- Ogunsanmi AO, Akpavieso PA, Anosa VO (1994) Serum Biochemical changes in WAD Sheep experimentally infected with Trypanosoma brucei. Tropical Veterinarian 47(2): 195-200.

- Fiennes RNRE, Jones, Laws SG (1946) The course and pathology of T. congolense (Broden) desease of cattle. Journal of Comparative Pathology 46: 1-27.

- Sow A, Zabré MZ, Mouiche MMM, Kouamo J, Kalandi M, et al. (2014) Investigation of Biochemical Parameters in Burkinabese Local Small Ruminants Breed Naturally Infected with Trypanosomosis. International Journal of Biochemistry Research & Review, 4(6): 666- 679.

- Chaudhary ZI, Iqbal J (2000) Incidence, biochemical and haematological alterations induced by natural trypanosomosis in racing dromedary camels. Acta Tropica 77: 209-213

- Awobode HO (2006) The biochemical changes induced by natural human African trypanosome infections. African journal of biochemistry 5(9): 738-742.