Medicinal Music: Music Therapy in End of Life Care

Racheal Bell*

MS(N) Program, Western Carolina University, USA

Submission: May 04, 2017; Published: June 08, 2017

*Corresponding author: Racheal Bell, MS (N) Program, Western Carolina University, 64 Vance Ave Black Mountain, NC 28711, Tel: 828-545-3355; Tel: havenchiah@yahoo.com

How to cite this article: Racheal Bell. Medicinal Music: Music Therapy in End of Life Care. J Complement Med Alt Healthcare. 2017; 2(4): 555592. DOI:10.19080/JCMAH.2017.02.555592

Abstract

Purpose: This literature review examines the use of music therapy and its effects on the negative symptoms often associated with end of life and palliative care.

Data Sources: An electronic database search was used to collect articles for this literature review in the following databases: Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, CINAHL Complete, CINAHL Plus with full text and psychlNFO. Evaluated studies were both qualitative and quantitative.

Implications for Practice: The universal appeal of music makes it possible for nearly every individual to relate to music and participate in music therapy in meaningful ways. It is important that nurse practitioners and other primary care providers understand and are aware of this treatment modality so they may offer it to their patients, if appropriate. Music therapy can be used on almost any patient of any age, background, or culture. It can be a complement to other therapies or used on its own. Music therapy is versatile and safe making it an excellent tool for all providers to use.

Conclusion: Analysis of the studies found that music therapy is effective for meeting the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of patients and families. Music was helpful in reducing physical and emotional symptoms, while supporting spiritual beliefs, inspiring life review, and discovering meaning from the dying process. Qualitative studies showed that music therapy improved quality of life for patients at the end of life.

Introduction

Death and bereavement are experiences that everyone will have to go through at some point in life. Distress, pain, and grief can become unbearable for both the hospice patient and family members during the final stages of life [1]. It is helpful to provide a therapeutic and sacred space for emotional expression of one's worries and fears related to death, and to support relationship reconciliation in the last stages of life rather than letting grief and distress go unresolved [2]. Music therapy can help to serve as a channel for releasing such unresolved feelings and finding peace and closure at the end-of-life [2]. According to O'Callaghan et al. [3] patients often draw from their musical lives and explore music to remain connected with pre-illness identities, strengthen capacity for enduring treatment and ongoing survival (even when knowing "you're going to die”), face death, reframe upended worlds, and live enriched lives. Music therapy has also been shown to provide benefit to the family caregivers. According to Krout [4] responses to music therapy interventions with family caregivers include: decreased anxiety, shared positive experiences and improved communication, more open expression of feelings, stimulation of shared life review, enhanced relaxation capacity, increased sense of community support, and the development of a more humanistic view of medical personnel.

Music therapy is an established allied health profession. It is a growing service provided in end-of-life care, with music therapists gaining employment opportunities in hospices and as members of palliative care teams in hospitals each year [5]. Music therapists are board certified (MT-BC) by the Certification Board for Music Therapists (CBMT) upon completion of at least an undergraduate degree in music therapy or its equivalent [5]. In hospice and palliative care, music therapists use methods such as song writing, improvisation, guided imagery, lyric analysis, singing, instrument playing, and music therapy relaxation techniques to treat the many needs of patients and families receiving care.

History of Music Therapy

Music is a medium that has long been used to promote spiritual and physical wellness. It has a longstanding history as a therapeutic tool in healing practices. Dating as far back as 500 B.C., during the time of the ancient Grecians, music has been recognized for its therapeutic properties [6]. However, music therapy as a treatment modality in hospice care is relatively new. Needs often treated by music therapists in end-of-life care include a social (e.g. isolation, loneliness, boredom), emotional (e.g. Depression, anxiety, anger, fear, frustration), cognitive (e.g. neurological impairments, disorientation, confusion), physical (e.g. pain, shortness of breath) and spiritual (e.g. lack of spiritual connection, need for spiritually-based rituals) [5].

The 20th century profession formally began after World War I and World War II, when community musicians of all types, both amateur and professional, went to veterans' hospitals around the country to play for the thousands of veterans suffering both physical and emotional trauma from the wars. Patients' notable physical and emotional responses to music led the doctors and nurses to request the hiring of musicians by the hospitals. It was soon evident that the hospital musicians needed some prior training before entering the facility and so the demand grew for a college curriculum [6].

The first training program for music therapists was established in 1944 at Michigan State University. Six years later, the National Association for Music Therapy (NAMT) was founded in the United States (US). In 1971, another national organization, the American Association of Music Therapy (AAMT), came into being. In 1998, the two organizations came together to join forces and form the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA). In 2010, the AMTAcelebrated 60 years of development and growth. Due to the subsequent development of music therapy training programs worldwide, music therapy has become a recognized professional health care modality [7].

Hospice and Palliative Care

The term "hospice” can be traced back to medieval times when it referred to a place of shelter and rest for weary or ill travelers on a long journey. The name was first applied for specialized care in dying patients in 1948 by Dame Cicely Saunders. It was at this time that Saunders began working with the terminally ill and went on to create the first modern hospice, St. Christopher's Hospice, in a residential suburb of London (History of Hospice Care, 2016). Saunders introduced the idea of specialized care for the dying to the US during a 1963 visit to Yale University. In 1974, Florence Wald, along with two pediatricians and a chaplain, founded Connecticut Hospice in Branford, Connecticut. Shortly after this first hospice house was founded, musicians and music therapists became an integral part of the end-of-life care team.

Hospice is the model of high quality, compassionate care that helps patients and their families live as fully as possible with the focus being on caring, not curing (History of Hospice Care, 2016); focusing not on dying, but on living until you die. Providing compassionate patient centered care at the end of life provides hope and encouragement to both patients and their families for a peaceful and meaningful death. It values life and affirms death as just another event in life that should be honored and valued.

Palliative care is a holistic approach to provide relief to patients who are suffering from life threatening illnesses. In most clinical situations, the principal aim is to cure the disease and relieve symptoms; however, in palliative care, the main goal is to improve the quality of life of patients as well as their families who are facing complex issues associated with the disease. This occurs mainly through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification, comprehensive assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems encompassing the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual domains [8].

There are differences between palliative care and hospice. Palliative care is whole-person care that relieves symptoms of a disease or disorder, whether or not it can be cured. Hospice is a specific type of palliative care for people who likely have six months or less to live. In other words, hospice care is always palliative, but not all-palliative care is hospice care.

Purpose

The purpose of this literature review is to enhance health care providers' knowledge concerning the benefits of music therapy at the end of life. It will provide a look at some of the uses of music therapy for patients' physical, emotional, and spiritual well being as well as discussing some of the commonly used music therapy interventions. In doing so, healthcare providers can be equipped with current music therapy clinical interventions and goals in end of life care. Knowledge of common interventions and goals can help healthcare providers ensure positive therapeutic outcomes for patients and families in end-of-life care.

Methodology

An electronic database search was used to collect articles for this literature review in the following databases: Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, CINAHL Complete, CINAHL Plus with full text and psychINFO. Keywords used to search these databases were as follows: music therapy, music therapy and hospice, music therapy and palliative care, music therapy and end of life, music therapy and dying, music therapy for pain, music therapy for anxiety, music and spirituality and complementary and alternative medicine. Inclusion criteria consisted of the following:

- Studies on palliative care and music therapy, hospice care and music therapy, or end-of-life care and music therapy

- Studies between 2005-2016.

- Studies, including all age ranges.

- Studies written in English.

- Peer-reviewed studies.

- Studies providing specific details about music therapy interventions for end of life care.

Exclusion criteria consisted of the following:

- Any studies before 2005.

- Studies not written in English.

- Studies not involving a therapeutic relationship or music therapy.

- Books and book reviews, and

- Studies not related to or not specifying detailed music therapy interventions for end-of-life care. The search yielded 44 articles, 22 of which were utilized.

Literature Review

Existing quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies relevant to music therapy interventions in end-of-life care will De presented. Findings will De provided in a way that is useful for practicing clinicians. Qualitative research on music therapy is abundant, which comprised the majority of the research studies. This type of research aims to achieve a better understanding through first-hand experience, truthful reporting, and quotations of actual conversations, which makes it perfect for studying the way music touches someone emotionally and spiritually. As a result, experimental and quantitative research on music therapy is limited but growing.

Goals of Music Therapy

Physical comfort

One of the first things most often addressed Dy the music therapist is the promotion of physical comfort. When overall comfort is addressed and managed, patients and their loved ones are more at ease and the dying process is more peaceful. Some of the physical goals that might be addressed are pain, restlessness, anxiety, nausea, sleep disorders, agitation, and stress. Pain management is greatly important in hospice/palliative care to facilitate physical comfort. Many physical symptoms that are present in patients can often be attributed to physical pain itself. Music has been found to be effective for the management of acute pain, cancer pain, and procedural pain [9].

Hilliard [5] found there was a significant improvement in quality of life among terminally ill who were suDjected to a single session of live music therapy. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) Hilliard sampled 80 adult participants receiving hospice care in their homes for a terminal cancer diagnosis. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental or the control group. The experimental group received the same routine hospice services that the control group received with the addition of live music therapy, with a music therapist coming into their home and playing music for the patient. Hospice Quality of Life Index Revised (HQOLI-R), Palliative Performance Scale, and physical status assessments were administered to all.

Quality of life for the experimental group was not only higher than that of the control group, but it was also found that the more music therapy sessions, participants received, the higher the quality of life, even as their physical health declined. This was not the case in the control group, where the quality of life declined as physical status declined. The findings of this study support the idea that live music, therapy sessions increase perceived quality of life for people with terminal cancer, and that sessions should be provided with a relatively high frequency since the quality of life increased with each music therapy session. Similarly, Gallagher et al. [10] reported the effects of music therapy on 200 patients with a significant improvement in the facial expressions, mood, and verbalization of the patients (p< 0.001).

In a quantitative study Dy Krishnaswamy [11], a comparative study was on 14 cancer patients admitted for pain relief under the Department of Pain and Palliative Medicine of a tertiary care hospital who were experiencing moderate to severe pain (numerical pain rating scale [NRS] of 4 to 10). Convenience sampling was used. Patients were allocated to a test group or control group non-randomly. The test group patients were suDjected to music therapy for 20 minutes while the control group patients were kept occupied by talking to them for 20 minutes. The NRS scale was used to assess the pre- and postinterventional pain scores and the Hamilton anxiety-rating scale was used to assess the pre- and post-interventional anxiety scores in the two groups. Student's t-test was used for comparing the pre- and post-interventional data.

Two sample t-test was used to compare the data oDtained from the control and study groups. Statistically significant reductions were seen in the pain scores in the test group after music therapy (p=0.003). No statistically significant reduction was seen in the pain score in the control group (p=0.356). There was a statistically significant reduction in the post intervention pain scores in the test group compared to the control group (p=0.034). Reduction in anxiety levels in Doth groups after intervention was not statistically significant.

Emotional expression

Expression and discussion of feelings of loss and grief can be very difficult for terminally ill patients. Through the use of music, the music therapist establishes a nonthreatening supportive environment, which helps patients to express themselves. Expressing their emotions can help these patients experience a more relaxed and comfortaDle state [1].

It is helpful to provide a therapeutic and sacred space for emotional expression of one's worries and fears related to death and relationship reconciliation in the last stages of life rather than letting grief and distress go unresolved [2]. Music therapy can help to serve as a channel for releasing such unresolved feelings and finding peace and closure at the end-of-life [2]. It is evident that music therapy holds the power to facilitate emotional expression and exploration of loss and grief issues in the terminally ill [10].

Anxiety reduction

Anxiety is a very common physical symptom for all patients diagnosed with a terminal illness, regardless of a predisposition [12]. In fact, anxiety and depression have been found to be the most frequent psychological problem in palliative care [12]. Anxiety can become extremely debilitating and increases as patients become aware of their impending death. Horne- Thompson & Grocke [12] found that music therapy significantly reduced anxiety for terminally ill patients after a single session. This study was comprised of 25 palliative care patients ranging in age from 18 to 90 years.

Participants were either randomly assigned to an experimental group that received a single music therapy session or a control group that received a volunteer visit. The Edmonton symptom management scale (ESAS) and a pulse oximeter were used in a pre-test/post-test design. The Results of the measures indicated eight of the 13 participants in the experimental group had a significant decrease in anxiety as compared to the control group where only one of the 12 participants noticed a decrease in anxiety. In addition, it was also found that music therapy significantly reduced pain, tiredness, and drowsiness.

Meeting spiritual needs

Spirituality is a domain of health care that for some time was overlooked with more emphasis being placed on physical needs and how to treat or cure disease [13]. Now, as the philosophy of treating the whole person becomes standard practice, spirituality is becoming more integrated into the approaches of health care providers. Often those under duress, such as those with a terminal diagnosis, turn to spirituality for help seeking support to cope with difficult events. It has been suggested that while terminally ill patients may experience various physical symptoms, it is the complex psychosocial and spiritual needs that may be more distressing. These needs may not only be more distressing for patients to experience, but for families and friends to observe [13].

Subsequently, music therapists may encounter unique challenges when working with patients while tending to spiritual needs. McClean et al. [14] conducted 23 in-depth telephone interviews with people who had taken part in music therapy sessions. The researchers did not seek to establish clinical outcomes, and the small sample did not allow systematic evaluation of issues such as the relationship between cancer diagnosis, sociodemographic background, and music therapy Rather, an exploratory approach was taken in order to understand the subjective impact of a one-time group music therapy session; a number of themes emerged from the participants' accounts relating to notions of spirituality and healing.

A qualitative coding process was adopted in order to make analytic interpretations of the interview data. The focus was on findings relevant to notions of spirituality and healing, drawing on Magill's four overarching themes of transcendence, connectedness, search for meaning, and faith and hope. The result of the study emphasized meaningfulness, group connectedness and harmony, and a transformative experience that lends itself to musical creativity and identity discovery [14].

Added benefits

Life review: Music is an effective tool for evoking memories that can be used to review one's life and may be more effective than verbal review [15]. Life review is an evaluation of one's life; it is a universal process for people facing death. Hospice patients often look back at their lives in order to understand life meaning and their current situation. Music therapy can play a unique role in guiding life review because music evokes memories and feelings. Patients may recall memories by singing, playing and listening to music, and then they may participate in verbal discussions to explore life events.

The purposes of life review include a reexamination of one's life, resolution of conflicts, and transmission of knowledge and values to future generations [15].

A life review can help a patient move toward acceptance of death by giving meaning to the life lived. As patients review memories of experiences, relationships, and places they have lived in their lives, they can evaluate the quality of their lives, reflecting on achievements and reviewing disappointments in an effort to bring an understanding of life's significance.According to Sato [15], eight outcomes associated with life review with hospice patients can be identified from a review of literature on the topic. These outcomes include

- Integration.

- Sustained hope.

- Positive changes in mood.

- Increased understanding of life's meaning.

- Emotional intimacy between patients and themselves

- Working through emotions.

- Awareness of what to do with the time left, and

- Increased rapport between the therapist and the patient.

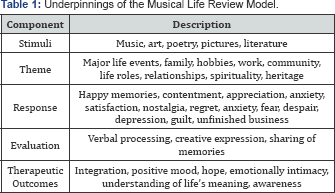

Self-reflection is a natural and important process for people at the end of life that can be better understood through the musical life review (MLR) model. The MLR model examines the process of life review, the role of music, and therapeutic outcomes [15]. It was developed by Yakimo Sato in 2011, based on a review and synthesis of literature regarding experiences conducting life review with hospice patients. The model consists of five components a) stimuli, b) theme, c) response, d) evaluation, and e) therapeutic outcomes (see Table: Underpinnings of the Musical Life Review Model). The therapist needs to consider musical elements, questions to open discussion, and the condition of the patient when guiding MLR. The Challenge lies in the therapist's ability to listen to patients and to understand the diversity of their backgrounds. Sogyal Rinpoche, a renowned Tibetan teacher, said, "Death is a mirror in which the entire meaning of life is reflected” [16]. When faced with death, we can't avoid looking at our past. Music therapists play a unique role in assisting this universal process- life review (Table 1).

Music Therapy Applications

Practicing patient-centered care in music therapy means the therapist looks at each patient individually and provides a music therapy intervention that Dest fits the patient's needs and goals. There are many different types of music interventions some of which involve live sessions or working with recorded music. Interventions of song writing, lyric analysis, music listening, singing and improvisation will be examined. However, these are not all inclusive of the vast array of music therapy applications. These modalities were selected for review because they are the most commonly used interventions. ]

Songwriting and lyric analysis

As a clinical approach in music therapy, creative songwriting leans on a tradition that is ancient and yet flourishes as an overtly contemporary art form. Songwriting can inspire deep thought and reflection aDout relationships and life.These practices can open up the door to healing longstanding emotional wounds between the patient, friends, and family. The songs are a powerful way to express our thoughts and feelings and to communicate important stories and messages. They can provide us with an opportunity to celebrate our lives, mourn our losses, and to preserve our history [17].

Listening and discussing the words of a song may facilitate the expression of many themes. Each person interprets music differently, and song lyrics can provide a springboard for discussion. When the client needs encouragement or assistance to express feelings, the therapist may present a song that has a theme for discussion. This technique provides a nonthreatening way for clients to open up. Stimulating cognitive function, facilitating the loss/grieving process, and regaining self-identity are other goals that can De achieved via lyric analysis [1].

Music listening

A therapeutic intervention the music therapist may use that is much more passive is just the seemingly simple act of listening to music. Passive interaction refers to lack of physical involvement with the music, such as moving or singing with the music; the patient, however, is engaged with the music and listens to songs actively. Because of the physical limitations, patients often face at the end of life, activities involving listening to music are commonly used by music therapists in palliative care; they are most convenient and easily instituted Dy nurses Black [18].

The therapist may play recorded music or live music. When playing live, the therapist can change the tempo or other qualities of a song, and if the therapist is playing recorded music the patient may appreciate the authentic voice, instrument, and/or feel of the song. Recorded music may bring back memories from the past and open the patient up to life discussion and life review. It may promote peace and comfort within a patient, reducing feelings of anxiety. Songs are ways that human beings explore emotions. They express who we are and how we feel; they bring us closer to others; they keep us company when we are alone. They articulate our beliefs and value. As the years pass; songs bear witness to our lives. They are our musical diaries, our life stories [19].

Singing

Singing a song can accomplish many nonmusical goals. For example, singing may help improve articulation, fluency, and Dreath control in speech. Individuals can also learn a new way of breathing using their diaphragm, which can enhance physical relaxation and reduce discomfort. Singing promotes social togetherness as patients, therapists, family members, and caregivers enjoy the lyrics and tune of the music together [20]. In the face of strong emotions, precomposed songs are the vehicles for expression. Family memDers and visitors can sing songs at the bedside, alone, or with the patient. Singing also helps the dying estaDlish new methods of self-expression and increase self-confidence.

Improvisation

In improvisation, clients may improvise a feeling or thought, or the client and therapist may actually create music together. For example, the therapist may encourage clients to play a percussion instrument, such as a drum, and improvise how they are feeling. Improvisation allows the client and therapist to enter into a dialogue that is not limited by words, yet somehow expressing and reaching a deep level of emotion. Many music therapists consider improvisation to be one of the most powerful techniques in palliative care music therapy, allowing patients the expression of issues that are often too difficult to articulate into words. Musical improvisation may facilitate the expression of emotions or themes that are not made evident verbally; improvisation may act as a catalyst for additional exploration in words and music [19]. Through improvisation, therapists use their musical skills to support, reflect, and encourage the client's musical creativity and expression; in much the same way as a counselor works in a verDal medium. Improvisation may also decrease a client's sense of isolation and promote relaxation. Family memDers can Denefit from taking part in improvisation with the client and therapist, or with the therapist alone, to help them express emotions that they are having trouble expressing [21].

Playing instruments may help motivate a client to participate, and in turn improve gross and fine motor coordination. It is part of many interventions to "promote participation, provide and alternate vehicle for self-expression, encourage choice making and focus attention” [1]. Percussion instruments can provide an outlet for all types of emotional expression, and rhythm creates a forum for sufficient emotional release, particularly for people who are not usually verbal about their feelings.Goals for this intervention are to promote participation, provide an alternate vehicle for self-expression, encourage choice making, and focus attention [1].

Discussion

Music therapy as part of an interdisciplinary approach can be an effective tool in meeting the needs of those, who in the face of illness and loss, are searching for meaning, hope, and acceptance [13]. Music is safe, inexpensive, and easy to use. Music is nonobtrusive and versatile making it an excellent choice as a complementary modality added to the treatment plan for almost any patient.

Various types of music therapy interventions are available for use. Whether song writing, lyric analysis, music listening, singing, and/or improvisation are utilized depends on patient needs and goals. A music therapist treats the patient Dy first assessing the physical, emotional, and spiritual well-Deing of the patient and family memDers [12]. Goals and oDjectives are then planned based on the assessment; however, patient needs and goals may change as the patient nears closer to end of life. As changes occur within the patient, the type and plan for the music therapy can also change due to its versatility.

Nearing the end of life for example, a patient may no longer have the aDility to play music or sing, Dut perhaps can find much comfort and peace, by listening. Music means different things to different people and it is incumbent upon the therapist to learn as much aDout those differences as possiDle [22]. Patients should De encouraged to talk aDout types of music that Dring enjoyment and how it makes them feel. Specific music selections or types of music may have different effects for different people, and may have different effects for the same person at different times.

Perceiving music as a universal language may give some practitioners a false sense of safety, believing that multicultural concerns are not necessarily an issue for music therapy [22]. Of primary importance for music therapists working with culturally diverse clients is a knowledge regarding the role of music in their client's personal life and culture. Age, cultural, ethnic, and gender differences in music preferences need to be considered in order to provide culturally competent, patient centered care. Qualitative studies make up the majority of research support in the area of hospice and palliative care music therapy, but there is a dearth in the literature of empirical quantitative studies. Because dying is a complex experience, more research needs to De conducted to evaluate the efficacy of the support provided for patients with a terminal illness.

Although qualitative studies are valuable in illustrating the use of music therapy for the terminally ill, Hilliard [5] cautions that reliability and the ability to generalize results can be limiting. It is recommended that researchers conduct quantitative studies Decause the advantages of clearly defined outcome measures include the minimization of potential researcher bias in the interpretation of results and also in the testing of hypotheses. Furthermore, quantitative studies provide greater assurance of reliability and results can be more readily generalized than those of qualitative studies.

Conclusion

Music therapy is a complex, personal, and deeply spiritual practice that Drings aid to all who are on the end-of-life journey It is a tool that emDraces culture, memories, and spirituality to create a restorative experience that is uniquely therapeutic to each person. By employing the restorative nature of music, music therapy allows hospice patients, families, caregivers, and the Dereaved to enjoy physical relaxation, mend emotional wounds, and recharge spiritually [20]. It has tremendous potential for addressing a variety of aspects in the care of terminally ill patients due to its wide capacity for accessing the human experience. Music is complementary to, not competing with, other therapies, and its specific use as a clinical mode of treatment has been shown to be effective in end of life care.

References

- Clements-Cortes A (2010) The role of music therapy in facilitating relationship completion in end-of-life care. Canadian Journal of Music Therapy 16(1): 123-147.

- Salmon D (2001) Music therapy as a psychospiritual process in palliative care.J Palliat Care 17(3): 142-146.

- O'Callaghan CC, McDermott F, Michael N, Daveson BA, Hudson PL, ZalcDerg JR (2013) A quiet still voice that just touches: Music's relevance for adults living with life-threatening cancer diagnoses. Supportive Care in Cancer 22(4): 1037-047.

- Krout R (2003) Music therapy with imminently dying hospice patients and their families: Facilitating release near the time of death. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 20(2): 129-134.

- Hilliard RE (2005) Music therapy in hospice and palliative care: A review of the empirical data. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2(2): 173-178.

- History of Music Therapy(2016) Music Therapy Featured in 2017 National Memorial Day Concert.

- CarrollD (2 011) Historicalrootsofmusictherapy:Abriefoverview.Revista do Nucleo de Estudos e PesquisasInterdisciplinaresemMusicoterapia, CuritiDa, Brezil, pp. 171-178.

- Ramanayake RP, Dilanka GV, Premasiri LW (2016) Palliative care; Role of family physicians.v J Family Med Prim Care 5(2): 234-237.

- Siedliecki SL, Good M (2006) Effect of music on power, pain, depression and disaDility. J Advanced Nursing, 54(5): 553-562.

- Gallagher LM, Lagman R, Walsh D, Davis MP, Legrand SB (2006) The clinicaleffects of music therapy in palliative medicine. Support Cancer Care 14(8): 859-866.

- Krishnaswamy P (2016) Effects of music therapy on pain and anxiety levels of cancer patients: A pilot study. Indian J Palliat Care 22(3): 307311.

- Horne-Thompson A, Grocke D (2008) The effect of music therapy in patients who are terminally ill. J Palliat Med 11(4): 582-590.

- Kidwell M(2014) Music therapy and spirituality: How can I keep from singing? Music Therapy Perspectives 32(2): 129-135.

- McClean S, Bunt L, Daykin N (2012) The healing and spiritual properties of music therapy at a cancer care center. J Altern Complement Med 18(4): 402-412.

- Sato Y (2016) Musical life review in hospice. Music Therapy Perspectives 29(1): 31-38.

- Rinpoche S (1992) The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. HarperCollins publishers, USA, p. 11.

- Heath B, Lings J (2012) Creative songwriting in therapy at the end of life and inbereavement. Mortality 17(2): 106-118.

- Black BP (2012) Music as a therapeutic resource in end-of-life care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 14(2): 116-125.

- O'Kelly J (2008) Saying it in song: Music therapy as a carer support intervention. Int J Palliat Nurs 14(6): 281-286.

- Music Therapy in Hospice: Using Music to Bring Comfort to the Whole Person. (2015) In Crossroads Hospice Charitable Foundation, USA.

- O'Kelly J (2002) Music therapy in palliative care: Current perspectives. Int J Palliat Nurs 8(3): 130-136.

- Julie MB (2002) Towards a Culturally Centered Music Therapy Practice. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy 2(1).