Abstract

Keywords:Climate-resilient; Environmental protection; Sustainable development goals; Sanitation technologies; Water pollution

Mini Review

Life without a toilet can be dangerous, dirty and undignified. Women substantially bear the most burden when there is poor WASH service delivery. Billions of people still do not have a safe toilet. Safe water supplies, sanitation and hygiene promotion remains vital for good health, environmental protection and poverty alleviation. It is encouraging that 94% of Uganda’s population has access to some form of sanitation facilities however, access to improved sanitation remains low: just 34% overall and 26% in rural areas. The quality of sanitation facilities has always been compromised. Pit latrines are commonly used both in rural and urban communities. With challenges of limited land, effects from floods and poor drainages associated with pollution, low-cost climate resilient sanitation solutions remains the best option. This manuscript share Amref Health Africa in Uganda experience in promoting the double leach pour flush toilets in Kabarole and Bunyangabu in Uganda.

AMREF Health Africa in partnership with Caritas HEWASA Fort Portal are implementing the Financial Inclusion Improve Sanitation and Health (FINISH) to improve WASH service delivery in Kabarole, Kamwenge, Kyenjojo and Bunyangabu Districts. The project contributes to the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 3 (Good Health and Well Being) SDG 6 (Clean water and sanitation), SDG 13 (Climate Action).

The focus is on households that do not have improved sanitation facilities. Technologies being promoted are low cost and climate resilient, thus enabling the low-income earners to buy a technology of their choice. In addition, service delivery has been brought closer to the people through strengthening the supply chain (by training masons) thus making it easy for everyone within the target areas to demand for sanitation services. The same has been made of the sanitation products, bringing down the cost and increasing their availability. Among the low-cost climate-resilient sanitation technologies promoted is the double leach pour flush toilet.

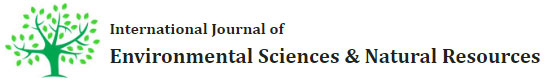

The double leach pour-flush toilets are improved pit latrines, which allow on-site treatment and transformation of feacal sludge into a hygienized soil amendment. They consist of two pits, linked with a Y-junction to a single pour flush toilet. Often pits are placed symmetrically at the back of the latrine in order to have good access and ensure drainage from the user interface to the pits (Figure 1).

If the site condition does not permit this layout, the pits can be placed on the side or even in front of the toilet pan, but this design requires more water for flushing (Roy et al. 1984). The toilet can be constructed inside the house, while pits can be situated outside the house. However, the pits should not be situated in drainage lines, the paths of storm water drains or in depressions where water is likely to collect in order to prevent water from entering the pits which can cause ground water pollution or destabilize the construction.

The pit shape can be circular or rectangular, but circular pits are more stable and cost less. No matter how the system is designed, only one pit is used at a time. While one pit is filling, the other full pit is resting [1-4].

How it works

The size of the pits depends on the number of users. For a

family of 5 members, a pit of 1m deep and 1 metre round is enough.

a) Measures the external diameter of about 4.19ft or 1.28m.

b) Make sure the internal diameter is 3.44ft or 1.05m.

c) The depth of the pits can range from 7-10ft or 2.5-3m.

d) A pour-flush toilet (user pours water to flush) rather

than a full flush sewer system—appropriate for low-income,

rural/peri-urban contexts with limited infrastructure.

e) The technology is “simple tech, big impact” — meaning

it uses locally available materials, modest inputs, and can be

maintained at community/household level

f) It is more climate-resilient because the dual-pit design

can better cope with variable water tables, seasonal flooding

or drought, and shifting ground conditions in rural/peri-urban

zones (Figure 2-4).

Principle of operation

a) An inspection chamber with a Y “junction” is built

between the pits and the pan so that excreta can be channeled

into either pit.

b) When the first pit is full, the inspection chamber is

opened and the stopper blocking the outlet pipe removed and

placed in the other outlet pipe.

c) The content of the first pit is dug out after a period of at

least two years. Only after that period the content have become

less harmful.

d) Emptying is done manually using long handled shoves

and proper personal protection.

Cost

a) A pour flush toilet connected to a double pit latrine cost

between USD 472 to 555).

b) Actual cost will depend on the pit volume, the quality of

the lining, slab and superstructure.

c) Whether materials are available locally and local prices.

d) Operation and maintenance accounts for 1.5% of the

investment costs per year.

e) Because water is required for flushing, the price of water

has to be taken into account.

Other climate resilient sanitation technologies promoted

include

a) Lined Ventilated Improved Latrines (VIP).

b) Ecosan toilets - Fossa Alterna Latrine.

c) Double VIP toilet.

d) Flush toilets with septic tanks.

Outcomes, benefits & impact

a) The adoption of improved sanitation technologies has

increased the coverage of “improved toilets” in the region. For

example: in Kabarole improved toilet coverage rose to about 14

% and in Bunyangabu about 12% in the FINISH programme area.

b) Use of a double-pit pour flush system supports safer

waste containment (reducing contamination), lets households

adopt higher standard sanitation, and helps build resilience to

climatic stressors (e.g., flooding, high water tables).

Challenges & lessons

a) A major challenge is scaling up: although progress has

been made, full coverage is still far off. In Kabarole’s some subcounties

latrine coverage is still only around 40-50% and open

defecation remains in some villages.

b) Ensuring ongoing maintenance, community ownership

and local supply of materials is key to making the toilets last. The

MBS approach emphasizes training local masons and mobilizing

local resources.

Conclusion

This case study shows that in rural and peri-urban districts like Kabarole and Bunyangabu in Uganda, the use of a “double leach pit pour flush” toilet system presents a feasible, affordable, climate-resilient sanitation solution for low-income households. By combining simple technology with local implementation, community involvement and sustainable maintenance, the approach helps build healthier, more dignified sanitation facilities that can withstand climate pressures (e.g., flooding, high water tables) and contribute to achieving broader WASH goals.

References

- Amref Health Africa in Uganda. Turning the Tide: 6 Years of Restoring Health and Dignity through Sanitation in Uganda’s Rwenzori Region. Amref Health Africa in Uganda, Apr. 29, 2025.

- Amref Health Africa in Uganda (2025) FINISH Mondial: A Journey to Sustainable Sanitation at Scale. (Programme factsheet: Uganda, Rwenzori Region – Kabarole, Bunyangabu, Kamwenge, Kyenjojo).

- Engineering for Change (2025) Twin Pits for Pour Flush. Engineering for Change.

- Sulabh International. Two-Pit Pour-Flush Household Toilet. Sulabh International, (n.d.).

- Niwagaba CB, Batte A, Majara D, Katukiza AY, Mukisa A, et al. (2025) Faecal sludge accumulation and characterization in informal settlements of Kampala: insights for facilities design. Discover Sustainability 6(444).