Abstract

Cultural dimensions through Hofstede’s model provide a perspective to understand the differences in cultural attributes between rural and urban societies in Pakistan. This study examines Hofstede’s cultural dimensions-masculinity, power distance, and collectivism-across rural and urban areas of Punjab. The results indicate that rural residents exhibit higher masculinity, power distance, and collectivism compared to urban residents. These findings can assist policymakers, local governments, educational authorities, human rights organizations, and NGOs in developing strategies to improve societal standards. This study is the first to investigate Hofstede’s cultural dimensions at rural and urban levels within Pakistan, highlighting both opportunities and challenges for development in a culturally diverse country.

Keywords:Masculinity; Power distance; Collectivism; Rural; Urban

Abbreviations:LTO: Long-Term Orientation; UA: Uncertainty Avoidance; EFA: Exploratory Factor Analysis

Introduction

Culture shapes the way people perceive the world, interact with others, and organize their lives. From daily social interactions to societal structures, cultural norms influence behavior, expectations, and relationships. Understanding these cultural patterns is particularly important in countries like Pakistan, where rural and urban communities coexist with distinct lifestyles, traditions, and social dynamics. Investigating how cultural dimensions vary across these areas provides valuable insights into human behavior, social organization, and policy development.

The present study aims to compare the cultural dimensions of masculinity, power distance, and collectivism in Punjab province, Pakistan, across rural and urban areas. Research interest in cultural influences has grown significantly, as understanding cultural differences is essential for interpreting social behavior, shaping policies, and guiding societal development. Hofstede’s five-dimensional model of culture is deeply embedded in the socio-cultural system of Pakistan and offers a systematic framework for examining these differences.

Culture can be defined as the shared understanding that individuals use to interpret interactions and generate social actions. It is often the product of relationships over time, reflecting unique practices, norms, and values among groups and communities [1]. Culture plays a critical role in shaping national identity, defining ethnic groups, and influencing social behavior. Scholars have long emphasized the importance of cross-cultural studies, both at the global level and within individual countries, to understand the variations in human behavior. Since Hofstede introduced the cultural dimensions model in 1980, researchers have increasingly applied it to explore differences not only across countries but also within distinct societal segments, such as rural versus urban populations, different social classes, genders, and generations [2].

Values and cultural norms embraced from early childhood are deeply ingrained and influence behavior throughout life. These embedded cultural attributes often give rise to distinctive societal patterns and may reinforce divisions between communities. Understanding how cultural dimensions manifest in different geographical and social contexts is therefore essential to uncovering their impact on behavior and social organization [3]. Customs, norms, and values are accepted and transmitted through culture, making it a major concern for communities and policymakers alike [4].

Despite the growing body of literature on cultural dimensions in Pakistan, few empirical studies have examined provincial and national cultural patterns, and most research has focused on general cultural consequences [5,6]. Rural-urban cultural differences, in particular, remain largely unexplored. This study addresses this research gap by investigating the differential expression of masculinity, power distance, and collectivism among rural and urban residents of Punjab. By comparing these two populations, the study seeks to provide a more comprehensive understanding of cultural diversity within a single country, contributing to both theoretical knowledge and practical policy implications.

The findings of this study are expected to benefit government officials, policymakers, women’s rights organizations, and nongovernmental organizations by providing insights into ethnic, social, and cultural diversity among rural and urban populations. Understanding these differences can help design effective policies and interventions aimed at promoting equality, social development, and empowerment.

Accordingly, the research question guiding this study is: Are Hofstede’s cultural dimensions-particularly masculinity, power distance, and collectivism-more pronounced among rural respondents compared to urban respondents in Punjab, Pakistan, and how might these cultural differences relate to the persistence and practices of dowry in these communities?

Significance of the Study

This study holds critical importance for contemporary society, particularly for adults and the younger generation, as it exposes entrenched cultural norms that continue to shape social behavior and reinforce systemic inequalities. By examining the differences between rural and urban areas in Punjab, the research highlights how deeply ingrained practices, such as gendered power hierarchies, excessive dowry customs, and collectivist pressures, perpetuate discrimination, limit educational and professional opportunities for women, and constrain individual freedoms. In today’s rapidly changing social context, understanding these disparities is essential to challenge outdated norms and promote progressive change.

The findings of this study serve as an evidence-based tool for policymakers, educators, and social activists to design targeted interventions aimed at reducing gender inequality, curbing exploitative practices, and empowering women across all regions. By raising awareness among adults and youth, this research encourages critical reflection on inherited customs, fostering a mindset that questions inequity rather than accepting it as tradition. Implementing reforms based on these insights can not only transform family and community structures but also ensure that future generations are nurtured in a society that prioritizes fairness, gender equality, and opportunities for all. In essence, this study is not merely academic; it is a roadmap for cultural transformation, equipping today’s generation with the knowledge and motivation to confront harmful practices and actively build a more just and equitable society.

Literature Review

Culture

Culture can be defined as an intellectual and artistic achievement or expression, or as a customized appreciation of the humanities, traditions, and achievements of a specific society or group [1]. The literature also describes culture as the collective conditioning of the mind that distinguishes members of one group or class of people from others, emphasizing that it is fundamentally a group phenomenon. The term “culture” is widely used to describe tribes, ethnic groups, nations, and societies [2].

[7] identified several cultural models that provide researchers with frameworks for analyzing communities across cultures. While it is generally agreed that cultures are unique, the complexity of the concept makes it difficult to establish a single definition. Culture can also influence attitudes toward change, social behavior, and adaptation [7]. In the context of Pakistan, culture serves as both a backdrop and a source of discrepancies in everyday life, shaping perceptions, interactions, and societal norms.

Hofstede’s model, along with other frameworks such as those proposed by Hall and Nisbett, provides a systematic approach for understanding cultural differences. This study focuses on Hofstede’s relatively unexplored cultural dimensions of masculinity, power distance, and collectivism, examining their presence and impact in rural and urban areas of Pakistan. Evaluating the applicability of Hofstede’s work in this context is a challenging yet important task [8].

Scholars have described culture as acquired knowledge that individuals use to interpret interactions and produce social behavior [9]. Cultural differences can be explored in numerous ways to understand their influence on attitudes, decision-making, and societal development. While previous research has presented regional findings and contrasted them with Pakistan’s national culture [1], rural-urban cultural distinctions remain largely ignored. Punjab, in particular, exhibits cultural characteristics closely aligned with national patterns, making it a suitable region for this study.

Masculinity reflects a society in which a strong distinction exists between social genders. In masculine cultures, women may be somewhat assertive and competitive, but not to the same extent as men, resulting in a gap between the values and expectations of men and women [2]. Literature indicates a strong cultural tendency toward masculinity in Punjab, with higher scores observed compared to other regions, highlighting pronounced gender-role differentiation [1,10].

Power distance represents the extent to which inequality among individuals is accepted and institutionalized within a society. It refers to perceptions of power and authority, and in high power distance societies, individuals from lower social classes are treated unequally, expected to obey norms, and show greater respect for established hierarchies [11,12]. Studies suggest that Pakistan exhibits a high level of power distance, reinforcing hierarchical social structures and obedience to authority [1].

Collectivism is a social orientation that emphasizes integration into groups, loyalty, and adherence to shared norms [2]. In contrast, individualism prioritizes personal interests over group cohesion. Pakistan scores low on individualism, indicating a highly collectivist society where people maintain long-term relationships with extended families and prioritize social harmony and loyalty [1,10]. Collectivism is a dominant aspect of the national culture, guiding behavior and social expectations across communities.

The Long-Term Orientation (LTO) dimension reflects a culture’s focus on future rewards, adaptability, and perseverance [1]. LTO evaluates how much a society emphasizes efforts toward the future, present, and past [13, 14]. Literature reports that Punjab exhibits low long-term orientation, with people valuing enjoyment, leisure, socialization, and immediate gratification over future planning [1,10].

Uncertainty Avoidance (UA) measures the extent to which individuals feel stressed in the face of an uncertain future and unstructured situations [2]. Low UA scores in Pakistan indicate that people are generally unconcerned about unpredictability and are comfortable navigating novel or ambiguous circumstances [1,10].

In the context of Punjab, literature suggests that Muslim residents tend to place less emphasis on long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance due to faith and trust in Allah. Instead, cultural attributes such as masculinity, power distance, and collectivism remain dominant [1,10]. This study builds on these contributions to deeply examine Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, focusing specifically on rural and urban residents of Punjab, a comparative approach that has not been previously explored.

Differential Effects of Cultural Dimensions for Rural Vs. Urban Area Residents

Even in the 21st century, women in male-dominated societies like Pakistan continue to face mental oppression and stress [15]. Masculinity, as a cultural dimension, reflects gender role distribution in society [11]. In masculine contexts, men are considered dominant, expected to pursue higher education, build successful careers, and regulate women’s behavior, including dress code and participation in activities outside the home, while also protecting them. Women, in contrast, are traditionally responsible for household and family duties and, particularly in rural areas, may have limited control over their earnings and personal decisions [16].

Islam, however, provides women with significant status and resources, emphasizing their equal importance in society. Women are granted independence and autonomy, with the Holy Quran describing men and women as complementary components essential for the survival of humanity. The Quran designates men with responsibilities to care for their families, but societal misuse of this authority has led to gender inequality [17].

Power distance, another cultural attribute, highlights the extent to which inequalities in society are accepted and institutionalized [11]. It reflects how power is distributed and perceived within social hierarchies [18]. High power distance societies, such as rural regions in Pakistan, tend to follow conventional norms, with individuals treated unequally and expected to respect authority and hierarchy [12,19,20]. Urban societies, by contrast, with greater education and economic development, prefer lower power distance and more egalitarian structures [18]. Despite Islam granting women fundamental equality and legal rightsincluding the ability to earn, own property, and manage finances independently—these rights are often undermined by societal practices, leading to discrimination and even violence against women [17].

Collectivism, which contrasts with individualism, emphasizes group loyalty and prioritizing collective goals over individual interests [11,12]. Rural societies, characterized by larger family units and slower social development, tend to be more collectivist, whereas urban populations, exposed to modernization and social growth, display more individualistic tendencies [18].

The literature indicates that masculinity, power distance, and collectivism are key cultural dimensions influencing the lives of rural and urban residents differently in Punjab. Based on this, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1: Masculinity is higher among rural residents compared to

urban residents.

H2: Power distance is higher among rural residents compared

to urban residents.

H3: Collectivism is higher among rural residents compared to

urban residents.

Measurement Instruments

To achieve the objectives of this study, all measures were adopted from previously validated scales. The cultural dimensions-masculinity, power distance, and collectivism-were measured using established instruments. Masculinity and power distance were measured with four items each, while collectivism was measured with six items. All items were assessed on a sevenpoint Likert scale, anchored from “fully disagree” (1) to “fully agree” (7).

The study employed the widely adopted scale developed by [14], which primarily measures cultural norms and customs. Each of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions was assessed directly to capture the differential effects at the individual level among rural and urban residents. This approach is considered superior to generic cultural measures because it allows for a more precise evaluation of how values and customs are influenced by culture and provides a more predictive understanding of cultural impact.

These measures were selected because they have been validated in prior studies focused on culture and have characteristics similar to those of Pakistani society, ensuring reliability and relevance in the current context.

Research Procedure and Questionnaire

The study was conducted across two distinct geographical areas of Punjab province, targeting both rural and urban populations. To ensure reliability, the questionnaire underwent four rounds of revisions, including pretesting and cross-checking procedures for each area. The items were updated as needed to reflect local contexts and ensure clarity and relevance for respondents.

To maximize accuracy and accessibility, the questionnaire was made available in both English and Urdu. In addition to demographic items, all questions measuring cultural dimensions were assessed using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “fully disagree” (1) to “fully agree” (7). This approach ensured that the instrument could effectively capture the perceptions and attitudes of respondents while accommodating language preferences and local nuances.

Data Collection

The survey targeted residents from two distinct geographical areas in the Punjab province of Pakistan: one group from rural areas and the other from urban areas. Data collection was conducted over a two-month period, from June to the end of July 2020, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To capture the depth of cultural attributes in both rural and urban populations, local residents were randomly selected, and the survey was distributed to obtain relevant information at the local level. Each participant was approached individually and asked to complete the questionnaire, which included items on gender, age, occupation, education, and other socio-demographic characteristics.

The study aimed to examine differences in Hofstede’s cultural dimensions-masculinity, power distance, and collectivismbetween rural and urban residents. Over the eight-week data collection period, 1,000 questionnaires were distributed, of which 770 were returned. After screening for completeness and usability, 650 questionnaires were considered valid, yielding an effective response rate of 65%.

Data Analysis Method

The statistical analysis for this study was conducted using SPSS (Version 22.0). SPSS was employed to ensure the reliability and validity of the constructs and to verify the research hypotheses. To examine differences between rural and urban respondents in Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, independent samples t-tests were applied. This approach allowed the researchers to determine whether the observed differences in masculinity, power distance, and collectivism between the two groups were statistically significant.

Demographic Characteristic

The study collected data from a total of 650 respondents, with 325 participants from urban areas and 325 participants from rural areas of Punjab province. The descriptive analysis of the demographic data shows that in the urban sample, 47.08% were male and 52.92% were female, whereas in the rural sample, 58.77% were male and 41.23% were female.

Factor Analysis and Reliability Test

To develop the final instrument and its possible subscales, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. Each factor was evaluated to determine whether a sufficient number of items had a factor loading greater than 0.40, as suggested by [21]. The analysis was performed separately for rural and urban residents. The results, presented in Table 1, indicated that the Cronbach’s alpha values for all variables demonstrated satisfactory reliability. All items exhibited acceptable factor loadings, with loadings of ±0.30 to ±0.40 considered minimally acceptable, and items with reliability coefficients above 0.60 were retained [22].

Hypotheses Testing

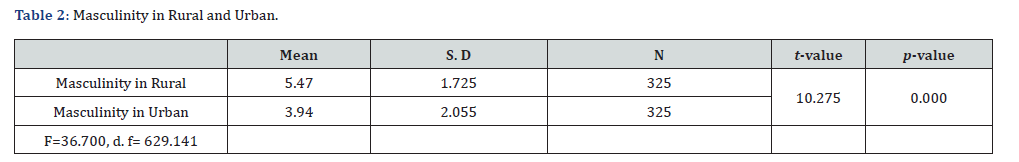

Masculinity

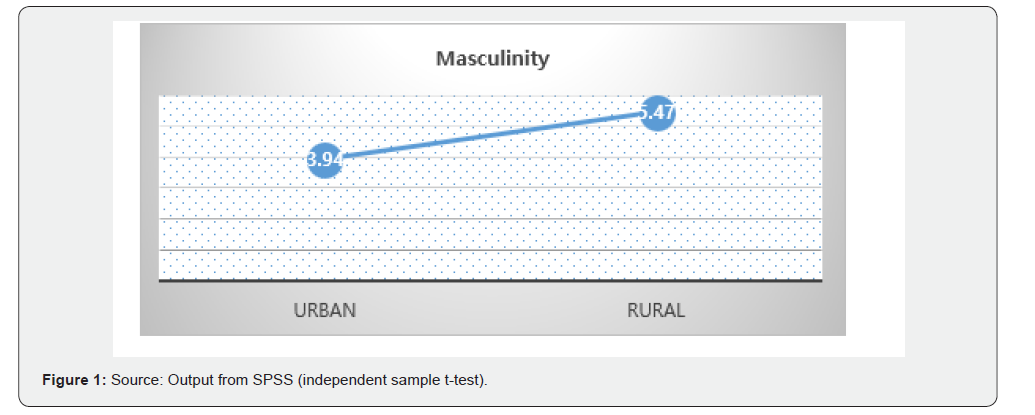

An independent sample t-test was applied to examine differences in overall masculinity between rural and urban residents. Hypothesis 1 proposed that masculinity would be higher among rural residents compared to urban residents. The t-test results, presented in Table 2 and Figure 1, indicate that rural residents scored higher on masculinity than urban residents. The t-value and p-value (p = 0.000 < 0.05) demonstrate that this difference is statistically significant. Thus, H1 is supported, confirming that masculinity significantly differs between rural and urban residents, with rural residents exhibiting higher masculinity.

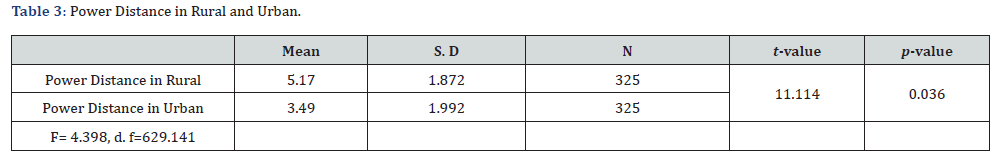

Power distance

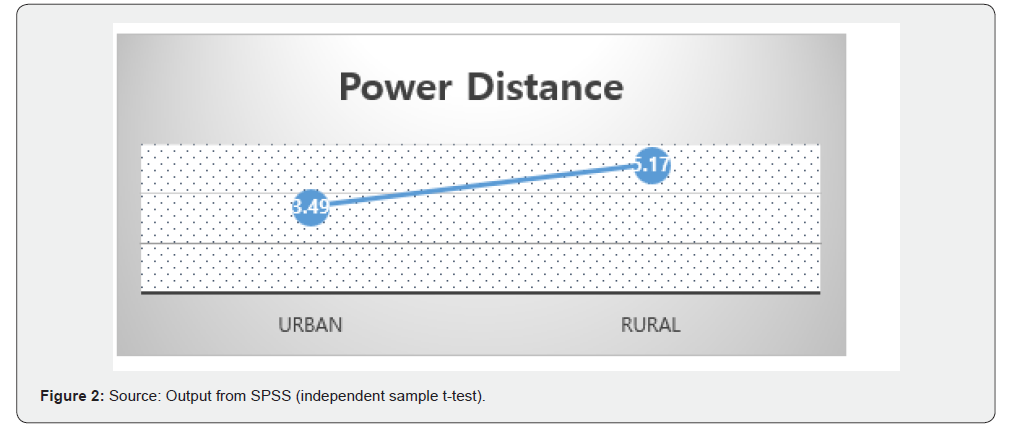

To assess differences in power distance, an independent sample t-test was conducted. Hypothesis 2 predicted higher power distance among rural residents than urban residents. The results, shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, indicate that rural residents scored higher on power distance compared to urban residents. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.03 < 0.05). Therefore, H2 is supported, and the findings suggest that rural and urban residents significantly differ in power distance, with rural residents demonstrating higher power distance.

Source: Output from SPSS.

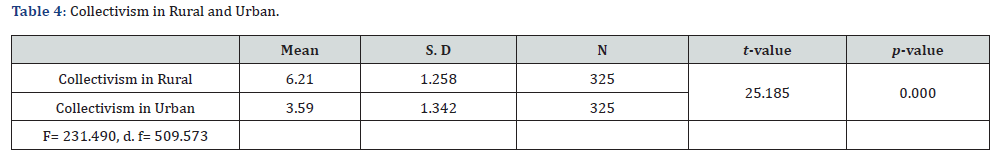

Collectivism

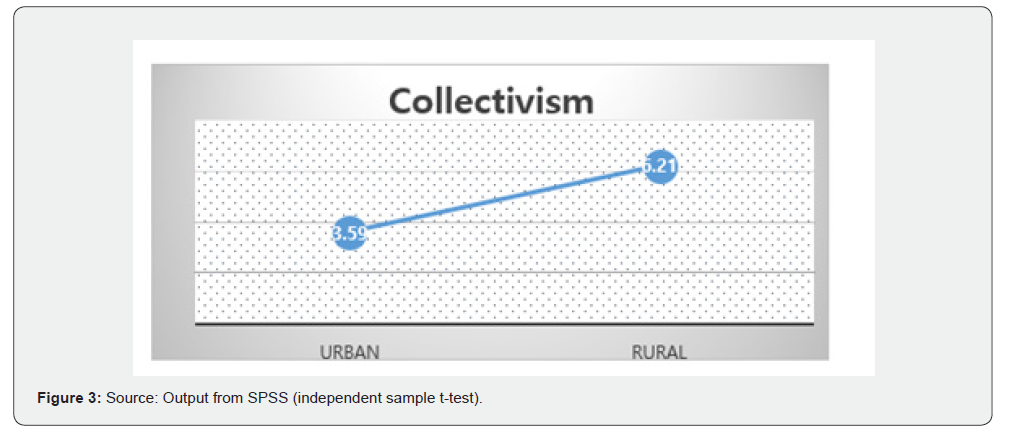

An independent sample t-test was also performed to examine differences in collectivism between rural and urban residents. Hypothesis 3 posited that collectivism would be higher among rural residents. The results, presented in Table 4 and Figure 3, show that rural residents scored higher on collectivism than urban residents. The difference is statistically significant (p = 0.000 < 0.05). Hence, H3 is supported, indicating that collectivism significantly differs between rural and urban residents, with rural residents displaying higher collectivism.

Conclusion

The primary aim of this study was to identify the differences in cultural dimensions between rural and urban residents of Punjab province, Pakistan. Conducting research in this region is challenging due to limited availability of official national statistics. Nevertheless, the study provides empirical evidence demonstrating significant differences in Hofstede’s cultural dimensions-masculinity, power distance, and collectivismbetween rural and urban areas. The findings indicate that these cultural dimensions are considerably higher in rural regions compared to urban regions within the same province.

Demographic characteristics further highlight the disparity: rural areas tend to have lower levels of education, particularly among women, which contributes to higher masculinity, power distance, and collectivism. In contrast, urban areas show higher female participation in education and employment, resulting in lower adherence to traditional gender roles and more egalitarian social practices.

Consistent with prior research [16], rural men are perceived as dominant, pursuing higher education and careers, while controlling women’s behavior, dress code, and social activities. Women in rural areas are primarily responsible for household and family duties, often with limited educational opportunities and autonomy. Collectivist family structures in rural societies enforce obedience to elders, limiting women’s decision-making power. Despite Islamic teachings granting women equal rights and autonomy [17], these principles are frequently overlooked, leading to inequality and psychological stress among women.

This study is the first of its kind to examine the implications of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in rural versus urban Punjab. By focusing on masculinity, power distance, and collectivism, this research contributes to understanding how cultural norms and values shape social behaviors and gender roles in different geographic contexts [23].

Theoretical and managerial implications are substantial. Policymakers, women’s rights organizations, and NGOs can use these findings to implement targeted strategies to reduce gender inequality and promote female empowerment. Encouraging higher education and employment opportunities for women can gradually diminish the influence of masculinity and high-power distance, fostering a more equitable society. Long-term application of these interventions is likely to promote greater gender equality, femininity, and social harmony for future generations.

Limitation and Recommendations for Future Research

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the data were collected only from rural and urban areas of Punjab province, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other provinces of Pakistan or to other Asian countries. Future research should expand the geographic scope to include more diverse regions and cultural contexts to enhance the applicability of results. Second, while the sample size of 650 respondents was substantial, additional diversity in terms of age, occupation, and socio-economic status could provide a more nuanced understanding of cultural influences. Third, cultural norms are dynamic and may evolve over time under the influence of modernization and globalization. Longitudinal studies are recommended to track changes in rural and urban cultural attributes and their impact on social behavior. Fourth, high masculinity, power distance, and collectivism may have significant psychological consequences, especially for women, such as stress, depression, and dissatisfaction, which were not explored in this study. Finally, incorporating intersectional variables such as religion, caste, and income levels could provide a deeper understanding of how cultural dimensions interact with other social factors.

In terms of recommendations, the findings suggest that policymakers and women’s rights organizations should focus on promoting educational and employment opportunities for women, particularly in rural areas, to reduce gender inequality. Awareness programs emphasizing women’s rights in accordance with Islamic teachings could help counter traditional cultural misinterpretations and empower women to participate more fully in social and economic life. Furthermore, cultural practices such as expensive and high dowry customs, which are more common in neighboring countries like India, highlight the importance of cross-cultural comparisons. Examining the cultural dimensions of India and comparing them with Pakistan could provide insight into whether similar patterns of masculinity, power distance, and collectivism exist or differ due to local customs. Interventions should be culturally sensitive, addressing local norms while gradually fostering more egalitarian social structures. By implementing such measures, rural populations may experience reduced pressures and enhanced social equity, ultimately contributing to a more balanced and inclusive society.

References

- Shah SAM, Amjad S (2011) Cultural diversity in Pakistan: national vs provincial. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 2(2): 331-344.

- Hofstede G (2011) Dimensional zing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online readings in psychology and culture 2(1): 2307-0919.

- Kumar R (2020) Dowry System: Unequal zing Gender Equality, pp. 170-182.

- Kamruzzaman M (2015) Dowry related violence against rural women in Bangladesh. Age (years) 15(4): 3-7.

- Ali TS, Árnadóttir G, Kulane A (2013) Dowry practices and their negative consequences from a female perspective in Karachi, Pakistan-a qualitative study. Health 5(7A4): 84-91.

- Makino M (2019) Marriage, dowry, and women’s status in rural Punjab, Pakistan. Journal of Population Economics 32: 769-797.

- Oshlyansky L (2007) Cultural models in HCI: Hofstede, affordance, and technology acceptance (Doctoral dissertation, Swansea University).

- Beugelsdijk S, Kostova T, Roth K (2017) An overview of Hofstede-inspired country-level culture research in international business since 2006. Journal of International Business Studies 48(1): 30-47.

- Hodgetts RM et al (2006) International Management, 6th Edition, McGraw Hill, Irwin, p. 93.

- Salman M (2015) Hofstede dimensions of culture: A brief comparison of Pakistan and New Zealand. SSRN 2702787.

- Hofstede G (2003) Cultural dimensions. www. Geert Hofstede. com, consulta, p. 13.

- Valaei N, Rezaei S, Ismail WKW, Oh YM (2016) The effect of culture on attitude towards online advertising and online brands: applying Hofstede's cultural factors to internet marketing. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising 10(4): 270-301.

- Bearden WO, Money RB, Nevins JL (2006) A measure of long-term orientation: Development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34: 456-467.

- Yoo B, Donthu N, Lenartowicz T (2011) Measuring Hofstede's five dimensions of cultural values at the individual level: Development and validation of CVSCALE. Journal of international consumer marketing 23(3-4): 193-210.

- Ali S, Shah M, Ashraf S, Tariq M (2017) The Practice of Dowry and its Related Violence in District Swat. Pakistan Journal of Society, Education and Language (PJSEL) 3(2): 100-112.

- Kamal S (2016) Comparative Analysis of Masculinity & Femininity in Pakistan, A Qualitative Study: The United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

- Bhattacharya S (2014) Status of women in Pakistan. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 51(1).

- Basabe N, Ros M (2005) Cultural dimensions and social behavior correlates: Individualism-Collectivism and Power Distance. International Review of Social Psychology 18(1): 189-225.

- Dodd SD, Patra E (2002) National differences in entrepreneurial networking. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 14(2): 117-134.

- Parboteeah KP, Hoegl M, Cullen JB (2008) Managers' gender role attitudes: A country institutional profile approach. Journal of International Business Studies 39: 795-813.

- Guadagnoli E, Velicer WF (1988) Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol Bull 103(2): 265.

- Wu HC, Cheng CC (2013) A hierarchical model of service quality in the airline industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 20: 13-22.

- Gulzar S, Nauman M, Yahya F, Ali S, Yaqoob M (2012) Dowry system in Pakistan. Asian Economic and Financial Review 2(7): 784-794.