Mucosal Manifestations of Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Key Sign for Early Diagnosis

Aline Grasielli Monçale Campos*, Laísa Ezaguy de Hollanda, Louise Makarem Oliveira, Valeska Albuquerque Francesconi do Valle and Fabio Francesconi do Valle

Tropical Medicine Foundation Dr Heitor Vieira Dourado, Department of Dermatology, Amazonas, Brazil

Submission: December 17, 2018; Published: January 12, 2019

*Corresponding author: Aline Grasielli Monçale Campos, Tropical Medicine Foundation Dr Heitor Vieira Dourado, Department of Dermatology, Amazonas, Brazil

How to cite this article: Aline G M C, Laísa E d H, Louise M O, Valeska A F d V, Fabio F d V. Mucosal Manifestations of Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Key Sign for Early Diagnosis. Glob J Oto, 2019; 19(1): 556002. DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2019.19.556002

Abstract

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune, chronic and life-threatening disorders that involve acantholysis, resulting in blisters and erosions of the skin and mucous membranes. Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is the most common form of the condition, with the production of IgG autoantibodies against desmoglein 3, which is mainly expressed on the mucous membranes, and desmoglein 1, expressed on the skin epidermis. Involvement of the oral cavity is more often observed when it comes to PV, especially in areas vulnerable to frictional trauma, causing painful lesions. This disorder may interfere with eating, leading to dysphagia, and subsequent weight loss, malnutrition, hydro electrolytic imbalances, and increased catabolism, enhancing the risk of local and systemic diseases. PV is associated with high morbimortality rates, whether it be because of the disease itself or because of complications that might follow the treatment. Therefore, the recognition of these lesions in clinical practice, as well as their correct management with pharmacological and support measures is fundamental in order to improve the quality of life of the patient.

Keywords: Pemphigus Vulgaris; Mucosa; Desmogleins; Blisters; Treatment; Support

Abbreviations: PV: Pemphigus Vulgaris; PF: Pemphigus Foliaceus; DSG: Desmoglein; IV: Intravenous Therapy; PO: Oral Administration

Introduction

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune disorders that involve acantholysis, the loss of keratinocyte adhesion, and results in intraepithelial blisters and erosions in the skin and mucous membranes [1,2]. The two most frequently observed types of pemphigus are pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF). PV occurs more often in adults between 40 and 60 years and does not present any sex predilection [3,4]. Despite being the prevailing form of pemphigus, corresponding for up to 70% of the cases, PV is a rare disorder, with incidence rates ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 per 100,000 people per year.4,5,6 It is more common in Europe and in the United States of America, while PF is typically related to North African and South American populations. Both disorders are chronic, incurable and life-threatening. However, the mucosal involvement is associated with pemphigus vulgaris [4,5]. This dramatic and early feature of the disease causes dysphagia, weight loss, nosebleeds, hoarseness, hydro electrolytic imbalances, food shortages, increased catabolism, and enhanced risk of local and systemic diseases, ultimately determining higher mortality [4-6]. Along with the physical damages, PV also jeopardizes the patient’s quality of life due to its significant psychosocial impact [1].

Physiopathology of pemphigus vulgaris

In PV, the presence of autoantibodies against desmogleins damages the desmosomes, structures responsible for assuring keratinocytes’ adhesion. As a result, acantholysis occurs, leading to vesicles’ and blisters’ formation [4,5,7,8]. In most patients, the serum levels of the aforementioned autoantibodies are directly related to the severity of the disease [8]. The major immunoglobulin class associated with PV is IgG - particularly IgG4 subclass in active PV and IgG1 during remission [9,10]. Desmogleins are transmembrane glycoproteins that belong to the cadherin family and compose the desmosomes, anchoring junctions responsible for cell-to-cell adhesion. These structures are the cornerstone of one of the most cited theories about pemphigus physiopathology: the desmoglein compensation theory.

That theory addresses why skin lesions usually follow oral manifestations on PV - instead of the opposite. The explanation lies in the fact that PV-related autoantibodies primarily affect desmoglein 3, which is expressed mainly, but not exclusively, in the mucosa-more specifically in the basal and suprabasal layers of the epidermis. In about 50% of the cases, nonetheless, desmoglein 1, expressed everywhere in the skin, is also targeted [5,10-12].

According to this theory, we can conclude that PV can clinically present itself as:

A. Mucosal dominant pemphigus vulgaris: when there are only antibodies against desmoglein 3. Therefore, the mucosa is mainly affected due to the lack of desmoglein 1 expression., whereas the skin is spared, once Dsg1 compensates for the Dsg3 loss of function.

B. Mucocutaneous pemphigus vulgaris: when both desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 are targeted by autoantibodies, resulting in loss of cell-to-cell adhesion on the skin and mucous membranes.

Nevertheless, the desmoglein compensation theory does not fully clarify the disorder’s pathophysiology, since up to one-third of the patients present with discordant clinical and serological profiles [13,14] In light of this, other potentially significant factors regarding the disease are dietary habits[15,16] viruses infection [17] and a large variety of drugs -such as penicillamine, captopril, enalapril, penicillin, cephalosporin, and piroxicam [5,15,18,19].

Clinical manifestations

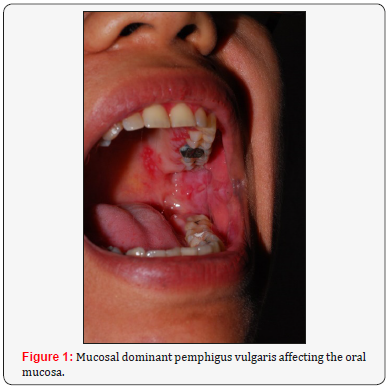

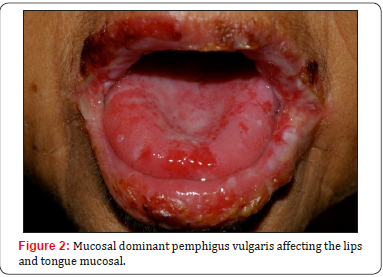

The main clinical feature in pemphigus involves the formation of blisters and vesicles within the epidermis of the mucous membranes and the skin. As the blisters are fragile, they are easily ruptured, resulting in painful erosions and ulcers. As has been clarified in pathophysiology, mucous membranes’ lesions typically appear first. Involvement of the oral cavity is common, especially in areas vulnerable to frictional trauma, presenting as widespread erosions and ulcers (Figures 1-3) at physical examination [4,5]. The most frequent sites of involvement in the oral cavity are the buccal mucosa and the palatine mucosa.

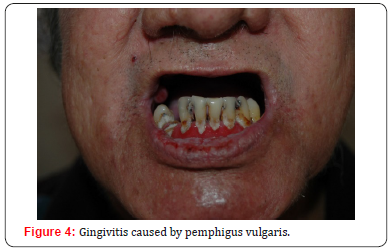

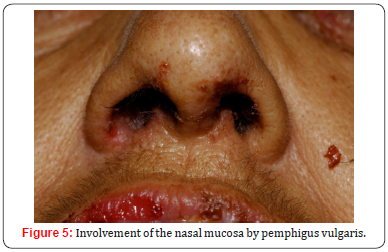

The lesions tend to be painful, interfering with eating and causing dysphagia, resulting in weight loss and malnutrition [8]. Furthermore, scaly or erosive gingivitis can occur (Figure 4), aggravating the general state of health [5]. Other mucous membranes may also be affected, such as the conjunctiva, nose (Figure 5), esophagus, larynx, pharynx, vulva, vagina, cervix and anus [8,20,21]. It is important to remember that the skin can be affected days to months after the onset of the disease. Thus, oral lesions are not rarely the only sign of the condition. Studies demonstrated that about five months of progression are necessary before the development of cutaneous lesions [22,23]. In the skin, PV usually presents with nonpruritic flaccid blisters on an erythematous or non-erythematous base that quickly turn into bleeding erosions. The lesions, which can be focal or generalized, are more common in seborrheic areas such as the face, the scalp, and the interscapular region. Flexural regions and extremities, which are vulnerable to stress and trauma, also are common sites of lesions [4,8].

Diagnostic methods

The diagnosis of pemphigus is based on a triad that includes clinical, histological and immunological findings [5]. In order to understand the general condition, as well as the comorbidities, it is mandatory to perform a thorough physical examination of the patient. Classically, there are two semiological maneuvers described for pemphigus: the Nikolsky Sign and the Asboe- Hansen signal (also called Nikolsky II signal). While the former includes the application of lateral pressure on the unaffected skin surrounding the lesion, the latter consists of the application of a vertical pressure in the blister. In both cases, epidermal detachment reveals disease activity

[8]. Histologically, a loss of cell adhesion between the basal and suprabasal layers of epidermis occurs in PV, resulting in acantholysis and retention of basal keratinocytes along the basement membrane area, and giving the appearance of a “row of tombstones”. Inflammatory infiltrates are absent or scarce with the presence of some eosinophils. Biopsy is extremely important in order to diagnose the type of pemphigus [4,5,10-12]. Direct immunofluorescence shows intercellular deposition of IgG with or without complement deposits (C3) on the keratinocyte plasma membrane. Indirect immunofluorescence detects circulating IgG antibodies by using different substrates, such as monkey esophagus, human skin, and guinea pig esophagus [4,5]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is the most sensitive (>90%) and specific (95%) test for detection of PV autoantibodies [4] It is particularly useful for monitoring disease activity and assessing treatment response [24,25]. Overall, immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation remain limited to the research scenario. Despite these tests’ efficacy in diagnosing pemphigus vulgaris, cost and availability issues prevent them from being further popularized.

Treatment considerations

Given the high levels of morbidity and mortality of this condition, treatment must be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is made. Before the advent of immunosuppressants, the mortality rate was 70 to almost 100% in 1 to 5 years [26-28]. The main goals of treatment are to induce a complete remission, minimize drug-related adverse events - once about 10% of the PV mortality rate is due to treatment complications [26,29,30] and improve the patients’ quality of life. The first-line treatment for PV is systemic corticosteroid therapy - prednisolone or prednisone with an initial dose of 1mg/kg/day. These drugs have the ability to reduce the levels of autoantibodies, nevertheless if used extensively and at high doses, they cause numerous side effects, among which infections, diabetes, and osteoporosis deserve to be highlighted.

The disease control phase is characterized by the absence of new lesions and by the healing of the established ones. When there is no new lesion for two weeks or when 80% or more of the lesions are healing, the treatment consolidation phase starts, and the corticosteroid dose should be reduced at 25% rate every two weeks, aiming to provide proper weaning from the medication, avoiding complications such as adrenal insufficiency. If the disease remains active or if there is no response within 2 weeks, the corticosteroid dose should be increased to 1.5 to 2mg/kg/ day [1,5,8,31] If there is still no response to this therapy in two weeks, or if complications are noticed, the physician should consider the second-line treatment: azathioprine 50mg once a day for two weeks (with a progressive increase for up to 3mg/ kg/day) or mycophenolate mofetil 500mg once a day (with weekly increase for up to 2 to 3g/day) [1,5,8,31]. Some patients do not respond to these treatments, requiring third-line drugs such as: rituximab (375mg/m² once a week for 4 weeks, or 1g two doses with a two-week interval), dapsone (100mg/day or 1.5mg/kg/day), methotrexate (10 to 25mg/week - associated with folic acid 5 to 15 mg/week), cyclophosphamide (500mg IV or 2mg/kg/day PO), immunoglobulin (2g/kg/monthly cycle), and plasmapheresis [5,8,31]. Other than drug therapy to stop disease activity, additional measures can help to support the patient with pemphigus, such as [8,32,33]:

a. Break large blisters sterile, leaving the blister layer on top to reduce the chance of infections

b. Use of systemic or topical anesthetics, such as lidocaine 2%

c. General care with erosions and ulcers (use of local emollients, non-adhesive dressings, cleaning, topical antibiotics)

d. Adequate dental hygiene and professional dental cleanings

e. Nutritional support in cases of pemphigus vulgaris mucosa, with a change in nutritional status

f. Avoid spicy, hard, abrasive or very hot foods

g. Monitoring oral candidiasis and herpes

h. Corticosteroid mouthwashes for extensive oral lesions

i. Psychological support

Conclusion

Because of the chronic and incurable nature of pemphigus, as well as its high morbimortality implications, recognition of lesions requires a high level of suspicion. Although it is a rare disease, pemphigus vulgaris should be thought of whenever facing recurrent, painful, erosive, and non-improving oral lesions so that the treatment can be introduced as soon as possible. In addition to the multiple options of drugs and therapeutic regimens currently available for pemphigus, supportive measures are of utmost importance, playing a vital role in minimizing patient suffering and reducing the chances of complications arising not only from the disease itself, but from its treatment, with the final goal to improve the patients’ quality of life.

References

- Martin LK, Agero AL, Werth V, Villanueva E, Segall J, et al. (2009) Interventions for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1: CD006263.

- Mihai S, Sitaru C (2007) Immunopathology and molecular diagnosis of autoimmune bullous diseases. J Cell Mol Med 11(3): 462-481.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA (2011) Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin 29(3): 405-412.

- Joly P, Litrowski N (2011) Pemphigus group (vulgaris, vegetans, foliaceus, herpetiformis, brasiliensis). Clin Dermatol 29(4): 432-436.

- Mignogna M, Fortuna G, Leuci S (2009) Oral pemphigus. Minerva Stomatol 58: 501-518.

- Kneisel A, Hertl M (2011) Autoimmune bullous skin diseases. Part 1: Clinical manifestations. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 9(10): 844-856.

- Meyer N, Misery L (2010) Geoepidemiologic considerations of autoimmune pemphigus. Autoimmun Rev 9(5): A379-A382.

- Hertl M, Jedlickova H, Karpati S, Marinovic B, Uzun S, et al. (2015) Pemphigus. S2 Guideline for diagnosis and treatment - guided by the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) in cooperation with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). JEADV 29(3): 405-414.

- Bhol K, Natarajan K, Nagarwalla N, Mohimen A, Ahmed AR (1995) Correlation of peptide specificity and IgG subclass with pathogenic and nonpathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus vulgaris: a model for autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92(11): 5239-5243.

- Ding X, Aoki V, Mascaro JMJ, Lopez Swiderski A, Diaz LA, et al. (1997) Mucosal and mucocutaneous (generalized) pemphigus vulgaris show distinct autoantibody profiles. J Invest Dermatol 109(4): 592-596.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, Koch PJ, Amagai M, et al. (1999) Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest 103(4): 461-468.

- Siddiqui S, Haroon MA, Hasan S, Khalid A (2016) Desmoglein Compensation Theory: An explanation for Early Appearance of Oral lesions as Compared to Skin Lesions in Pemphigus Vulgaris. International Archives of BioMedical and Clinical Research 2(3): 13- 17.

- Jamora MJ, Jiao D, Bystryn JC (2003) Antibodies to desmoglein 1 and 3, and the clinical phenotype of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 48(6): 976-977.

- Sardana K, Garg VK, Agarwal P (2013) Is there an emergent need to modify the desmoglein compensation theory in pemphigus on the basis of Dsg ELISA data and alternative pathogenic mechanisms? Br J Dermatol 168(3): 669-674.

- Brenner S, Bialy Golan A, Ruocco V (1998) Drug-induced pemphigus. Clin Dermatol 16(3): 393-397.

- Tur E, Brenner S Diet (1998) pemphigys. In pursuit of exogenous factors in pemphigus and fogo selvage. Arch Dermatol 134: 1460-1510.

- Ruocco V, Wolf R, Ruocco E, Baroni A (1996) Viruses in pemphigus: a casual or causal relationship? International Journal of Dermatology 35(11): 782-784.

- Korman NJ, Eyre RW, Zone J, Stanley JR (1991) Drug-Induced Pemphigus: Autoantibodies Directed Against the Pemphigus Antigen Complexes Are Present in Penicillamine and Captopril-Induced Pemphigus. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 96(2): 273-276.

- Darling M, Daley T (2006) Blistering Mucocutaneous Diseases of the Oral Mucosa - A Review: Part 2. Pemphigus Vulgaris. J Can Dent Assoc 72(1): 63-66.

- Kavala M, Altıntaş S, Kocatürk E, İ Zindancı, B Can, et al. (2011) Ear, nose and throat involvement in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: correlation with severity, phenotype and disease activity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 25(11): 1324-1327.

- Kavala M, Topaloğlu Demir F, Zindanci I, Burce C, Zafer T (2015) Genital involvement in pemphigus vulgaris (PV): correlation with clinical and cervicovaginal Pap smear findings. J Am Acad Dermatol 73(4): 655- 659.

- Dagistan S, Goregen M, Miloglu O, Çakur B (2008) Oral pemphigus vulgaris: a case report with review of the literature. Journal of Oral Science 50(3): 359-362.

- Taborda JFP (2014) Mecanismos das doenças da mucosa oral de causa autoimune. Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, p. 54.

- Ishii K, Amagai M, Hall RP, Hashimoto T, Takayanagi A, et al. (1997) Characterization of autoantibodies in pemphigus using antigenspecific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with baculovirus expressed recombinant desmogleins. J Immunol 159(4): 2010-2017.

- Zone JJ (2009) The value of desmoglein 1 and 3 antibody ELISA testing in patients with pemphigus. Arch Dermatol 145(5): 585-587.

- Bystryn JC, Rudolph JL (2005) Pemphigus. Lancet 366: 61-73.

- Grando SA (2012) Pemphigus autoimmunity: hypotheses and realities. Autoimmunity 45(1): 7-35.

- Lever WF (1953) Pemphigus. Medicine (Baltimore) 32(1): 1-23.

- Beissert S, Werfel T, Frieling U, Böhm M, Sticherling M, et al. (2006) A comparison of oral methylprednisolone plus azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of pemphigus. Arch Dermatol 142(11): 1447-1454.

- Cirillo N, Cozzani E, Carrozzo M, Grando AS (2012) Urban legends: pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis 18(5): 442-458.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM (2003) British Association of Dermatologists Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 149(5): 926-397.

- Pemphigus: Disease/Medical Condition (2017) College of Dental Hygienists of Ontario, Canada.

- Tommasi AF (2002) Diagnóstico em Patologia Bucal (3rd edn), Pancast, São Paulo, Brazil, p. 600.