An Email-Writing Intervention for Adults with Intellectual Disability Using an Email Checklist and ChatGPT

Yi-Fan Li1*, Chih-Tsen Liu2, Xin Dong3, Wen-Hsuan Chang4 and Hung-Ta Chien5

1Department of Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching, The University of Texas at San Antonio, USA

2Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan

3Department of Teacher Education, Nicholls State University, Thibodaux, USA

4Department of Educational Psychology, Texas A&M University, USA

5Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Texas A&M University, USA

Submission: June 14, 2024; Published: September 13, 2024

*Corresponding author: Yi-Fan Li, Department of Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching, The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78249, USA

How to cite this article: Yi-Fan L, Chih-Tsen L, Xin D, Wen-Hsuan C, Hung-Ta C. An Email-Writing Intervention for Adults with Intellectual Disability Using an Email Checklist and ChatGPT. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2024; 14(1): 555877.DOI:10.19080/GJIDD.2024.14.555877

Abstract

Writing is an important skill that helps individuals to convey their thoughts, ideas, and emotions to others. One important writing task is email writing. Individuals with intellectual disability may face challenges in expressing themselves fully through language, particularly in the form of emails. This study used an ABAB single-case withdrawal design to evaluate the effects of an email-writing intervention for two adults with intellectual disability. Maintenance and generalization phases were conducted to examine whether participants could maintain their email-writing skills and apply those skills to different email scenarios. The interventionist provided five email-writing lessons focused on five work-related request scenarios. The interventionist modeled each step on an email checklist and demonstrated how to use ChatGPT to aid in revising emails. Data were analyzed through visual analyses and calculation of Tau-U effect sizes. The results of the intervention suggest that it was effective in teaching individuals with intellectual disability to write emails.

Keywords: ABAB single-case withdrawal design; ChatGPT; Email writing; Intellectual disability; Intervention

Introduction

Writing is an important skill that helps individuals to convey their thoughts, ideas, and emotions to others. One important writing task is email writing. Email writing at work helps individuals to communicate with colleagues and supervisors. As a method of communication, email offers many advantages, such as convenience and accessibility. Skilled email writers understand how to convey their thoughts and ideas concisely in written form. Individuals with intellectual disability may face challenges in communication due to limited use of speech and inability to respond to and/or initiate a conversation, whether orally or in writing [1]. This limitation can extend to the organization of thoughts and the development of writing skills, as highlighted by Rodgers & Loveall [2]. Struggles with self-regulatory skills may further affect individuals with intellectual disability’s ability to articulate thoughts and ideas in written form [3]. Consequently, some such individuals may find it challenging to express themselves fully through language, particularly in the form of emails [4]. Individuals who face challenges in written expression may encounter difficulties in school, social, and workplace settings. Since written communication, such as texting or email, is a prevalent means of interaction with friends, colleagues, and work supervisors, these challenges can negatively affect various aspects of these individuals’ lives [5,6]. There is a critical need for individuals with intellectual disability to learn email writing for work purposes. Proficient email writing not only facilitates effective communication with others but also empowers individuals to express their own needs successfully.

Prior studies on email writing with individuals with disabilities

Prior email-writing interventions for individuals with disabilities suggest that these individuals can successfully write emails using a computer interface specifically designed for accessibility in accommodating their needs. Sohlberg et al. [7,8] demonstrated that a simplified and adapted computer interface could assist individuals with disabilities in writing emails. Individuals with disabilities were provided with various writing-prompt conditions on the electronic interface, and with the support of this prompting, they were able to successfully compose emails. Both studies also found that email enhanced social communication. Email writing increased individuals’ motivation to socialize and to communicate with others. Once individuals with disabilities learned how to use the electronic interface, they were eager to email someone they knew.

Using modeling and scaffolding, prior studies have shown that email-writing interventions can help individuals with disabilities to enhance email-writing quality. In Wang et al.’s [9] study, students with intellectual disabilities engaged in email exchanges with graduate students serving as their mentors. Through 15 weeks of such exchanges, supported by modeling and scaffolding in combination with independent practice, students with intellectual disabilities showed a gradual improvement in the quality of their email writing. Thiel et al. [10] observed that individuals with disabilities were able to enhance the quality of their email writing with scaffolding from writing-support software such as word-prediction programs, word banks, text-to-speech programs, and spell-check technology. Both Wang et al.’s and Thiel et al.’s studies indicated that a combination of modeling, scaffolding, and explicit instruction can effectively assist individuals in enhancing their email-writing skills. Further, consistent guidance and scaffolding provided by mentors and/or assistive-writing software can ultimately contribute to individuals achieving independence in composing emails.

An AI technology tool-ChatGPT

Recently and rapidly, artificial intelligence (AI) has become a tool of innovation across many fields. This innovative AI model generates human-like responses through large language models (LLMs), which generate text as a result of having absorbed huge volumes of text-based data, including books, academic articles, and any other printed and digital materials [11]. ChatGPT relies on user-input prompts to predict and generate words and phrases. Through its transformer-based neural-network architecture, the pre-trained model of ChatGPT holds over 200 billion parameters to allow a user’s prompt access to a complicated deep-learning model [12]. With the help of reinforcement learning and natural language processing, the fine-tuned process is comprehensively formulated on the basis of the prompt (OpenAI, 2023). ChatGPT exhibits versatility in natural language processing tasks. It is applied in various scientific, medical, and educational fields to perform tasks extending beyond the answering of questions and summarization of texts to the generation of new writing.

In the context of education, although there are concerns about academic integrity with ChatGPT [13], with appropriate guidance and policies, some educators are responding to this new AI program by thinking about how it can be used to benefit classroom learning [14]. ChatGPT has been integrated into daily routines to help teachers with tasks that contribute to heavy workloads, such as administrative paperwork, lesson planning, and curriculum writing [15,16]. Recent studies have shown that students can practice different aspects of writing through ChatGPT [17]. Crucially, ChatGPT can provide students with immediate feedback and comments based on the prompts they input [18]. For example, students can prompt ChatGPT to write drafts for different audiences, and they can practice comparing and evaluating those drafts to learn different writing styles. Su et al. [19] tested ChatGPT’s potential to support argumentative writing for language learners. Recognizing the importance of timely and effective feedback, they found that ChatGPT has the potential to assist language learners in structuring their argumentative writing. Most of the second-language learners studied by Yan [20] improved the quality of their writing through the use of ChatGPT. Students can use input prompts in ChatGPT to help modify their writing style and correct mistakes. In Li et al. [21], ChatGPT was shown to assist students in the writing of narrative short texts; students analyzed their initial writing drafts in comparison with the revisions provided by ChatGPT.

Although some interventions for individuals with disabilities have used technology as a support to improve writing [22,23], the use of AI technology for these individuals is an emerging practice. Used properly, ChatGPT can be considered a revolutionary tool to help individuals with disabilities monitor and expand their functional writing skills-for example, in the writing of emails. With a focus on nurturing essential workforce skills like email writing, ChatGPT should be introduced to individuals with disabilities so that they have options to choose the best tool to help them develop this essential skill.

Current study

Recognizing the significance of email writing in a professional context, it is imperative to address our limited knowledge disabilities effective interventions for improving the email-writing skills of individuals with intellectual disability. Prior studies have shown that email writing can improve an individual’s communication and social interaction [7,8]. Consistent support in the form of modeling, scaffolding, and feedback has been shown to enhance the quality of email writing [9]. To empower individuals with intellectual disability to write emails independently, the integration of technology into instruction, such as AI, is crucial. Individuals can prompt AI to provide continuous feedback on their attempts to compose emails on their own. As such, the primary purpose of the current investigation was to assess the effectiveness of an email-writing intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities using an email checklist and ChatGPT. Our study was guided by this research question: What are the effects of the email-writing intervention on the quality of email composition?

Method

Participants

Recruitment for this study began after approval from the appropriate institutional review board was obtained. We recruited participants in Taiwan. Research-study information was posted on social media to recruit participants, and participants were selected according to the following criteria: They (a) were identified as having a primary disability of intellectual disability; (b) had sufficient ability to operate the technology, such as using word-processing tools, email programs, or video-conferencing programs; (c) had willingness to participate in a study for 3-4 months; and (d) demonstrated a need to improve their professional email writing.

Three adults with intellectual disability met the criteria and expressed interest in participating in this study. However, one of them opted not to participate due to time conflicts. The two participants who did take part in the study had some experience using emails in a workplace. Both participants had never heard of ChatGPT before they participated in this study. They expressed that they did not know how to write a professional email for communication with colleagues and supervisors. They demonstrated the need to improve professional email writing, having been told that their email messages were like text messages, lacking certain elements such as a concise subject line and a greeting. Thus, they were interested in participating in the intervention.

Mary

Mary was a 26-year-old woman. She was identified as having a moderate intellectual disability. She had a full-time job as a car washer in a car wash. Although she had not enrolled in postsecondary education, she had expressed that it might be an option for her in the future. She was adept at using technology for communication, including texting, and posting on social media.

Sharon

Sharon was a 27-year-old woman. She was identified as having a mild intellectual disability. She had a full-time job as a hair stylist’s assistant. Prior to holding that position, she worked as a full-time janitor in different settings, including a beauty store and a hospital. She had been enrolled in postsecondary education but did not complete the program. She could use technology to communicate-for example, texting and posting on social media.

Setting

The first author was the lead investigator and served as the interventionist for all sessions. She was an assistant professor in a teacher-preparation program of special education. Before she became an assistant professor, she was an instructor for a postsecondary education program and a special education teacher in a high school, mainly teaching students with autism and intellectual disability. Her research interests focused on transition to employment and postsecondary education for students with disabilities. She had experiences teaching students to learn important transition skills, such as specific job-related skills and soft skills for employment.

The interventionist conducted five sessions per week, one session each day for 5 consecutive days. She asked the participants if they felt the session frequency was too intensive. Both participants said the session frequency was not too intensive, but they both expressed a hope that the experiment as a whole would not last too long (i.e., would be finished within 3 months). Originally, we conducted training via Zoom, using it to guide participants to access ChatGPT and to demonstrate how to use the tool. However, due to the participants’ unstable Internet connections, the interventionist used Zoom recordings to create the lesson-training videos. Participants watched these videos and used a social app to communicate instantly with the interventionist. In addition, the interventionist used the social app to provide email instructions and feedback to participants. If necessary, the interventionist invited participants to have an audio or video call on the app to provide more detailed instruction and feedback.

Materials

Since the participants were from Taiwan, all the instructional materials were created in Chinese, using Microsoft Word and Microsoft PowerPoint, and stored in a Google Drive. Each participant had her own folder labeled with a pseudonym. The instructional materials included an email-writing checklist and a PowerPoint introduction to ChatGPT.

Email-writing checklist

The email-writing checklist was one of the primary instructional materials used during intervention sessions. Participants used the checklist to monitor their progress and mark completion of each step. We incorporated visual prompts (i.e., pictures and written directions) in each step. The visual prompts guided the participants to complete email-writing tasks and to use ChatGPT to edit their drafts. The steps for participants to complete were as follows: (a) write an email subject line, (b) write the email recipient’s name, (c) start with an appropriate greeting, (d) write an email message with a clear intention, (e) add a closing and the sender’s name, (f) open ChatGPT, (g) enter the first draft into ChatGPT with a prompt (e.g., “revision suggestions” and “check grammatical errors”), (h) correct the draft based on ChatGPT’s feedback, (i) check overall appearance, and (j) email the draft. Participants marked off each completed step using a checkmark.

Powerpoint introduction to ChatGPT

The interventionist developed a PowerPoint introduction to ChatGPT to assist participants in registering for an account on ChatGPT. The presentation included step-by-step instructions, with screenshots, guiding participants through the account-creation process. Once participants had created an account, they used it to log in to ChatGPT. The interventionist then used PowerPoint to demonstrate how to use a prompt for interaction with ChatGPT, as detailed later (in the Training section).

Definition and measurement of dependent variables

The participants wrote emails in Chinese. Three dependent variables-email components, total words written, and total correct punctuations written-were scored by two raters to track participants’ performance.

Email components

This was the primary dependent variable. It was assessed using a holistic rubric, meaning that the components of an email were measured [24,25]: (a) write an email subject line, (b) write the email recipient’s name, (c) start with an appropriate greeting, (d) write an email message with a clear intention, and (e) add a closing and the sender’s name. Those are the five main email components, and each was worth two points. The total score was 10, with higher scores demonstrating better performance.

Total words written

Similar to previous studies [26], this second variable measured the total number of words written in the email. Proper usage, punctuation, numbers, typographical errors, and grammatical errors were ignored when calculating the total number of words written [27]. To ensure accuracy, we manually calculated the total number of words written.

Total correct punctuations written

This third variable measured a component that adds clarity to writing. Correct punctuation means that appropriate punctuation marks are placed to connect, break, and separate ideas or sentences. Punctuation marks also signify the ends of sentences. As with total words written, we manually calculated the total number of correct punctuations written to ensure accuracy. Incorrect punctuation was not included in our calculations.

Interobserver agreement

Two independent observers scored the participants’ email drafts. Before scoring independently, they practiced the scoring process for the three dependent variables until full agreement was met. Both observers scored all email drafts across both participants and all phases (60 total email drafts, 30 for each participant). Interobserver agreements were calculated by dividing the number of agreements by agreements plus disagreements. The agreement percentages for email components for Mary and Sharon were 87% and 83%, respectively. Our discussion about the disagreements for email components primarily centered on appropriate email closings as the two participants used different closings. For total words written, the agreement percentage for Mary was 90%, and the agreement percentage for Sharon was 93%. For total correct punctuations written, the agreement percentage for Mary was 87%, and the agreement percentage for Sharon was 90%.

Experimental design and data analysis

We used an ABAB single-case withdrawal design to evaluate the effects of an email-writing intervention for two adults with intellectual disability. The ABAB withdrawal design shows experimental control because it requires the repeated introduction and withdrawal of an intervention, with three potential demonstrations of effect [28]. We implemented six phases (conditions), with the first four having at least five data points each [29].

The effects of the intervention on the three dependent variables were evaluated in two ways. First, line graphs of the data were created, and visual analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the intervention had any effects on the participants’ email-writing skills. Three criteria recommended by Kazdin [30] were used in visual analyses: (a) immediacy of data change following the start of the intervention, (b) trend, and (c) minimal score overlap. Second, Tau-U effect size was calculated to quantify the effects of the intervention [31]. Tau-U served as an overlap index, calculated on the basis of the combination of Kendall’s rank correlation and the Mann–Whitney U test [32]. The Tau-U calculator on the Single Case Research website [33] was used to calculate Tau-U effect sizes.

Orientation

Before the baseline condition was introduced, participants were introduced to the study. We explained why professional email writing is important for their future careers. We also explained that the email writing in this study would be focused on making a request. Sometimes it can be challenging to make requests or to ask for help in a workplace. Writing an email to ask for help can assist individuals in communicating their needs to supervisors and colleagues. Finally, we discussed the study goals and procedures with the participants. Participants had the opportunity to ask any questions they had during orientation.

Baseline and withdrawal procedures

During baseline, the interventionist assessed email writing without intervention. Before the participants composed an email draft, they were able to choose an email scenario from a pool of five options: (a) asking to take leave, (b) seeking help from a supervisor, (c) seeking assistance from a work colleague, (d) scheduling a meeting with a supervisor, or (e) seeking an extension for completion of a job task. We asked participants to select the scenario they preferred to write about. In line with their preferences and workplace situations, Mary opted to write an email requesting leave, while Sharon chose to write an email about scheduling a meeting with a supervisor. The interventionist did not prompt the participants to respond, nor did she provide any instructional feedback during baseline. For the withdrawal conditions, the participants wrote an email without using the email checklist or ChatGPT; they simply wrote an email and sent it to the interventionist. Baseline and withdrawal sessions lasted 10–15 minutes.

Training

The first part of the training lasted 30 minutes on Zoom and focused on instruction in accessing ChatGPT. In plain language, the interventionist introduced a rationale for the use of ChatGPT, and she demonstrated how to access ChatGPT with the following steps: (a) Open internet browser, (b) type “ChatGPT” in the search box, (c) click on the ChatGPT website, (d) create an account, and (e) log in to the account. The interventionist modeled each step, and participants had an opportunity to practice the steps. The participants also learned how to use effective prompts to generate responses in ChatGPT. The interventionist demonstrated how to engage with ChatGPT by inputting a prompt, a sentence, or a phrase to start a conversation with ChatGPT. We used two prompts to facilitate the use of ChatGPT in improving email writing: revision suggestions and check grammatical errors. After a prompt is entered to initiate a conversation, ChatGPT will process it and respond accordingly. Although ChatGPT primarily operates in the English language, users can still input prompts in Chinese, and ChatGPT will provide responses in Chinese as well.

The second part of the training focused on how to write a professional email and use ChatGPT to check email writing. The interventionist modeled how to write a professional email using the following steps: (a) write an email subject line, (b) write the email recipient’s name, (c) start with an appropriate greeting, (d) write an email message with a clear intention, (e) add a closing and the sender’s name, (f) open ChatGPT, (g) enter the first draft into ChatGPT with a prompt (e.g., revision suggestions), (h) correct the draft based on ChatGPT’s feedback, (i) enter the second draft into ChatGPT with a prompt (e.g., check grammatical errors), (j) correct the draft again based on ChatGPT’s feedback, (k) check overall appearance, and (l) email the draft.

The interventionist used five lessons to provide instruction on email writing in different scenarios. In the five lessons, she modeled each step on the email checklist, guided the participants through the process of writing an email, and then gave them the opportunity to practice independently. This practice continued until the participants could, as evaluated by the interventionist, write all email components, and use ChatGPT to examine and correct their writing.

Intervention

After completion of training in the five lessons, participants selected an email scenario to write to. Interestingly, both chose to continue writing in the same scenario they chose in the baseline. Mary opted to write an email requesting leave; Sharon chose to write an email about scheduling a meeting with a supervisor. During the intervention phase, the participants used the email checklist to help them complete the email-writing task. After drafting their emails, they used ChatGPT to seek suggestions for revisions and improvements in grammar. The interventionist only provided assistance to participants if they experienced technical problems with ChatGPT.

Maintenance and generalization

To determine the effectiveness of the intervention over a period of time, a maintenance phase was introduced 2 weeks following intervention. During this phase, the participants used the email checklist to help them write their emails and used ChatGPT to help them revise their emails. To determine whether the participants could generalize their new email-writing skills to a different email scenario, a generalization phase was introduced immediately after maintenance. During this phase, the participants were asked to choose a different email scenario. Mary chose to write to the scenario about scheduling a meeting with her supervisor. Sharon chose to write to the scenario about seeking an extension for completion of a job task. The participants could again use the email checklist to help them write their emails and use ChatGPT to help them revise the emails.

Results

The results showed that participants’ email-writing skills improved dramatically after receiving the email-writing training. The main dependent variable was email components in the participants’ emails. The other two variables were total words written and total correct punctuation. Both Mary and Sharon showed immediate increases in all three dependent variables, and there was no obvious overlap between the data points across phases. All three dependent variables decreased to levels similar to those in the baseline phase when the intervention was withdrawn. The data showed increases again when the intervention phase was reintroduced. Thus, there were three demonstrations of data changes for each dependent variable, and the data showed a functional relationship between the intervention and email-writing skills for both participants. Further, both Mary and Sharon showed improvement in the quality of their email writing in the maintenance and generalization phases. The intervention in this study proved to be effective in improving the participants’ email-writing skills.

Mary

Email components

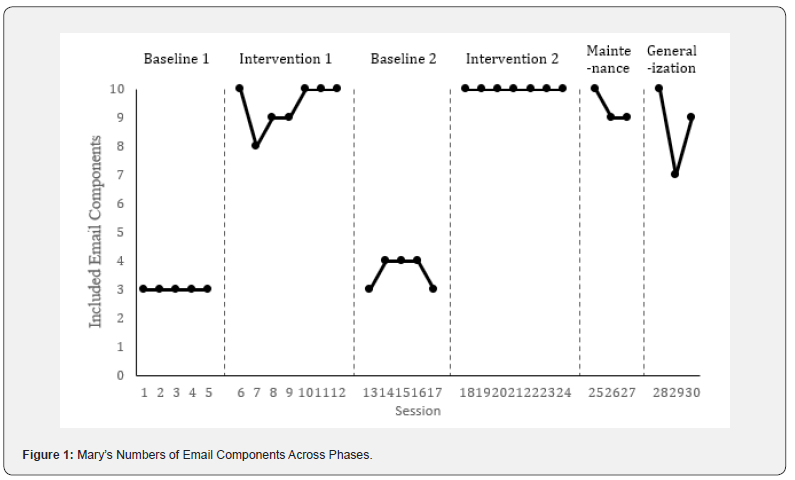

Mary’s numbers of included email components across phases are shown in Figure 1. Mary’s email-writing skills improved immediately after the introduction of the email-writing training. During baseline phase, her number of included email components was three across all five data points. When the interventionist started the email-writing training with Mary, her number of included email components increased from three to 10 for the first session after intervention. There was a little variation among the data points in the intervention phase (i.e., in Sessions 7-9), but the last three data points in the first intervention phase were all 10 components, and the average number of included components was 9.43 (range: 8-10). When the intervention was withdrawn and the baseline phase reinstated, Mary’s number of included email components dropped to three immediately, and her highest number of email components included in this second baseline phase was only four. Thus, the data showed that when the intervention was withdrawn, Mary’s included email components were reduced to levels similar to what was observed in the first baseline phase. For the second intervention phase, when the intervention was reintroduced, Mary’s number of included email components increased immediately from three to 10 again, and the number was stable across all data points in this second intervention phase. There was no overlap of data across phases for Mary’s numbers of included email components. Thus, there were three demonstrations of changes in the numbers of included email components across the phases, and the data showed a functional relationship between the intervention and the main dependent variable: number of included email components. Mary’s average number of included email components in the maintenance phase was 9.33 (range: 9–10), and her average number of included email components in the generalization phase was 8.67 (range: 7–10).

Total words written

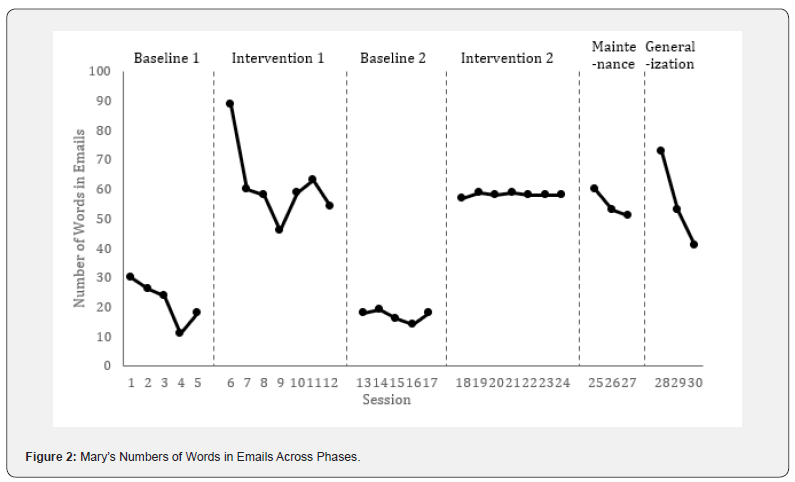

Mary’s total numbers of words in emails across phases are shown in Figure 2. Her number of words increased immediately after the introduction of the email-writing training. During the baseline phase, Mary’s average number of words in an email was 21.80 (range: 11–30), with a downward trend. When the interventionist started the email-writing training with Mary, her number of words in an email increased immediately from 18 to 89. Her average number of words in an email in the first intervention phase was 61.29 (range: 46-89). But there was a big variation in the intervention phase, with a downward trend also. When the intervention was withdrawn, Mary’s number of words in an email dropped to 18 immediately, and her average number of words in an email in the second baseline phase was 17.00 (range: 14-19). Thus, the data showed that when the intervention was withdrawn, Mary’s numbers of words in an email returned to levels similar to what was observed in the first baseline phase. When the intervention was reintroduced to Mary, her number of words in an email increased to 57, and her average number of words across the seven data points in the intervention phase was 58.14 (range: 57-59). The data were stable in the second intervention phase. Thus, there were three demonstrations of changes in the numbers of words in emails across the phases, and the data showed a functional relationship between the intervention and the number of words in an email. Her average number of words in the maintenance phase was 54.67 (range: 51-60), and her average number of words in the generalization phase was 55.67 (range: 41-73). Both the maintenance and the generalization data showed increases compared to the baseline phase.

Total correct punctuations

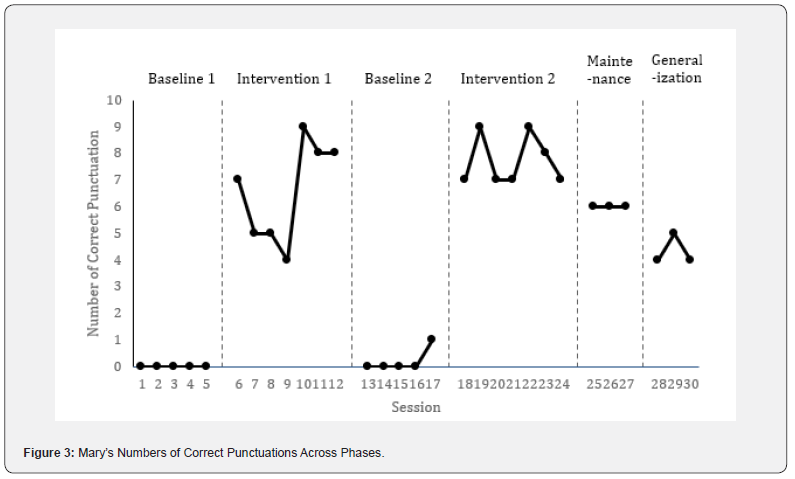

Mary’s total numbers of correct punctuation across phases are shown in Figure 3. Her number of correct punctuations was zero throughout the baseline phase. When the intervention was introduced with Mary, her number of correct punctuations increased immediately from zero to seven, with an average of 6.57 (range: 4–9). Although there was variation among the data points in the intervention phase (i.e., in Sessions 7–10), the trend was upward. When the intervention was withdrawn, Mary’s number of correct punctuations dropped to zero immediately. All her numbers of correct punctuations were zero except for the last datum for the second baseline, which was one-levels similar to what was observed in the first baseline phase. When the intervention was reintroduced, Mary’s number of correct punctuations increased from one to seven immediately, and her average became 7.71 (range: 7-9). The average level increased from the second baseline to the second intervention phase. Thus, there were three demonstrations of changes in the numbers of correct punctuations in emails across the phases, and the data showed a functional relationship between the intervention and the number of correct punctuations. Mary’s number of correct punctuations in the maintenance phase was consistently six, and the average of her numbers of correct punctuations in the generalization phase was 4.33 (range: 4-5). Both the maintenance and the generalization data showed an increase compared to baseline phase.

Tau-U effect sizes

Tau-U effect sizes were calculated for each dependent variable for Mary. Aggregated Tau-Us for the three dependent variables were all large. The Tau-Us for Mary’s included email components, total words written, and total correct punctuations written were, respectively, 1.00 (SD = 0.35), 1.00 (SD = 0.35), and 0.94 (SD = 0.35).

Sharon

Email components

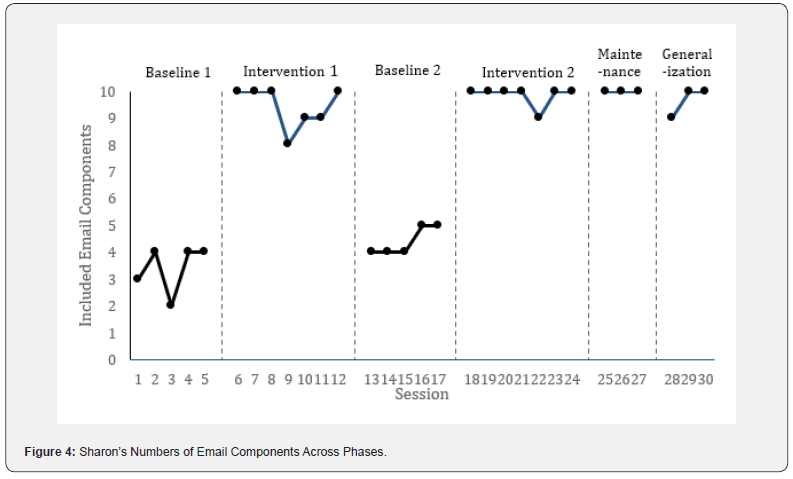

Sharon’s numbers of included email components across phases are shown in Figure 4. Sharon’s email-writing skills improved immediately after the introduction of the email-writing training. During the baseline phase, the number of included email components was 3.4 across all five data points. When the interventionist started the email-writing training with Sharon, her number of included email components increased from four to 10 for the first session after intervention. There was a little variation among the data points in the intervention phase (i.e., in Session 9-11), but the average of the data in the first intervention phase was 9.43 (range: 8-10). When the intervention was withdrawn and the baseline phase reinstated, Sharon’s number of included email components dropped to four immediately, and the highest number of email components included in this second baseline phase was only five. Thus, the data showed that when the intervention was withdrawn, the included email components were reduced to a level similar to what was observed in the first baseline phase. For the second intervention phase, when the intervention was reintroduced, Sharon’s number of included email components increased immediately from five to 10 again, and the number was stable across all data points in this second intervention phase, with an average of 9.86 (range: 9-10). Thus, there were three demonstrations of changes in the numbers of included email components across the phases, and the data showed a functional relationship between the intervention and the main dependent variable: number of included email components. Sharon’s number of included email components in the maintenance phase was always 10, and her average number of included email components in the generalization phase was 9.67 (range: 9-10).

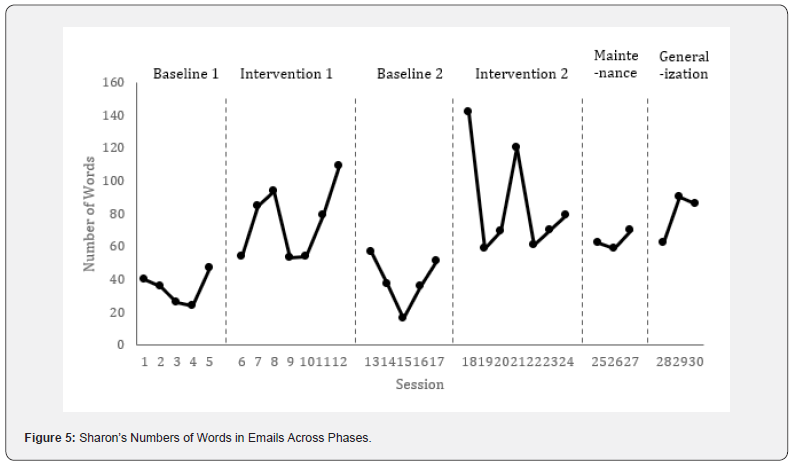

Total words written

Sharon’s total numbers of words in emails across phases are shown in Figure 5. During the baseline phase, the average number of words in an email was 34.60 (range: 24-47), with a slightly upward trend as Session 5 showed an increase. When the interventionist started the email-writing training with Sharon, her number of words in an email increased a little bit, from 47 to 54, in the first session of the intervention phase and then continued to increase, from 54 to 85, in the second session of the intervention phase. Sharon’s average number of words in an email in the first intervention phase was 75.43 (range: 53-109), with an upward trend with a steep slope. The data showed that the intervention increased the number of words from the first baseline to intervention phase (i.e., from 34.60 to 75.43). When the intervention was withdrawn, Sharon’s number of words decreased from 109 to 57 immediately, and her average number of words was reduced to 39.40 (range: 16-57). Thus, the data showed that when the intervention was withdrawn, Sharon’s numbers of words in an email returned to levels similar to what was observed in the first baseline phase. There was a little overlap between the data in the intervention phase and the data in the second baseline phase. When the intervention was reintroduced to Sharon, her number of words in an email increased from 51 to 142 immediately, and her average number of words across the seven data points in this intervention phase was 85.71 (range: 59-142). Sharon’s numbers of words in the maintenance phase and the generalization phase also showed increases. Her average number of words in the maintenance phase was 63.67 (range: 59-70), and her average number of words in the generalization phase was 79.33 (range: 62-90). Both the maintenance and the generalization data showed increases compared to baseline phase, with an average number of words of 34.60 (range: 24-47).

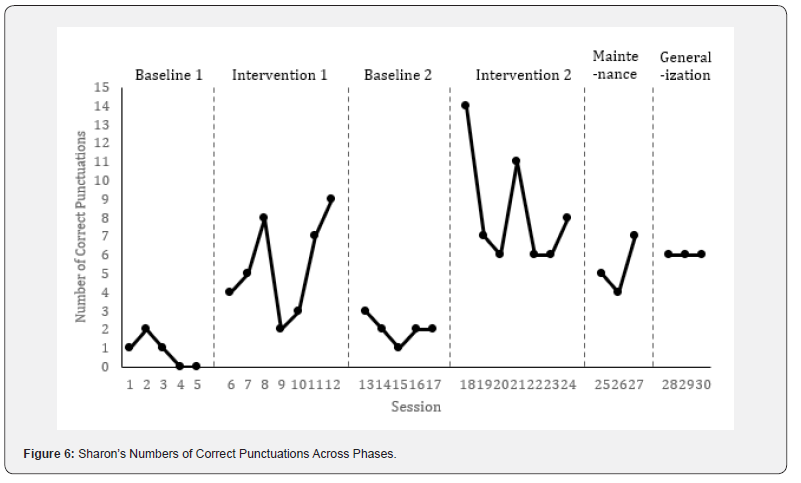

Total correct punctuations

Sharon’s total numbers of correct punctuation across phases are shown in Figure 6. Her average number of correct punctuations was 0.80 (range: 0-1) in the baseline phase. When the intervention was introduced with Sharon, her number of correct punctuations increased immediately from zero to four, with an average of 5.43 (range: 2-9). Although there was variation among the data points (i.e., in Sessions 9 and 10), the trend was upward. When the intervention was withdrawn, Sharon’s number of correct punctuations dropped to three, with an average of 2.00 (range: 1-3). The trend of the second baseline phase was downward, and there was a little overlap between the data points in the intervention phase and those in the second baseline phase. When the intervention was reintroduced, Sharon’s number of correct punctuations increased from two to 14 immediately, and her average became 8.29 (range: 6-14). Although there was variation among the data in the second intervention phase and the trend was downward, there was no overlap of the data between the second baseline phase and the data of the second intervention phase. Thus, there were three demonstrations of changes of the number of correct punctuations in emails across the phases, and the data showed a functional relationship between the intervention and the number of correct punctuations. Sharon’s average number of correct punctuations in the maintenance phase was 5.33 (range: 4-7), and her number of correct punctuations in the generalization phase was always six. Both the maintenance and the generalization data showed an increase compared to baseline phase.

Tau-U effect sizes

Tau-U effect sizes were calculated for each dependent variable for Sharon. Aggregated Tau-Us for three dependent variables were all large. The Tau-Us for Sharon’s included email components, total words written, and total correct punctuations written were, respectively, 0.87 (SD = 0.35), 1.00 (SD = 0.35), and 0.99 (SD = 0.35).

Procedural fidelity

To determine whether the intervention had been implemented following the procedure, the interventionist recorded all five training sessions on Zoom, and an observer was trained to evaluate the recordings for procedural fidelity. A procedural checklist was created, and the observer used the checklist to evaluate all recordings. The procedure on the checklist included the following: (a) First, the interventionist introduced and discussed the email scenario with the participants. (b) Second, the interventionist modeled each step on the email checklist (e.g., writing an email subject line.). The observer evaluated whether or not each procedure was correctly completed for all recordings. The procedure was completed with 100% fidelity.

Social validity

After the final generalization session, the interventionist invited participants to complete a brief survey with three open-ended questions regarding their experience of the intervention. The questions were as follows: (a) “How do you feel about the email intervention?” (b) “How do you feel about writing emails after receiving the intervention?” (c) “Is there anything you would want to change about the intervention?” In response to the first question, both participants expressed that the intervention was not challenging. They found it easy to use the strategy presented during the intervention. Regarding the second question, Mary shared that the intervention was instrumental in helping her understand how to write a professional email. She used ChatGPT to help her refine the tone of her emails. She said that she had previously struggled with using a formal tone in an email. Before receiving the intervention, she found that her emails were perceived as rude. ChatGPT helped her to write a professional email with an appropriate tone. Sharon expressed that the intervention helped her to focus on grammar, typos, and punctuation. She previously had not focused on these writing issues, so her emails were not perceived as professional. After receiving the intervention, she knew that she could use ChatGPT to enhance the quality of her writing. As to the third question, both participants indicated that they had no suggested changes for the intervention. However, they both mentioned that due to their full-time jobs, participating in the intervention after work could be a challenge. Despite this, they emphasized that the intervention had been very helpful.

Discussion

In the current study, we evaluated the effectiveness of an email-writing intervention comprising an email checklist and usage of ChatGPT. Both participants had intellectual disability, one at the mild level and the other at the moderate level. Although they had different levels of intellectual disability, both participants showed improvement in their email writing after they received the intervention. Before the intervention, both participants shared that it was challenging for them to write a professional email. They were accustomed to using texts or posting on social media to express their thoughts and did so often. They perceived email writing as different from their usual practice, even though composing a text message and posting on social media can be viewed as forms of writing practice [34].

Visual analysis of the data and Tau-U effect size calculations suggest that the intervention was effective in improving the participants’ email-writing skills as measured by three dependent variables. With respect to email components, both participants showed three demonstrations of changes between the baseline phase and the intervention phase. A professional email contains a concise subject line, a courteous greeting, a full message, and a polite closing. The results showed that after receiving the intervention, both participants could include all essential components in their emails, and both could use the email checklist to compose a professional email.

With respect to the total number of words written in an email, both visual analysis of the data and Tau-U effect size calculations showed that participants increased their numbers of words written in emails as a result of the training. During the baseline phase, the participants’ email messages were brief and lacked clarity; this was especially the case for Mary, who conveyed her message using only one sentence. In the intervention phase, both participants used more words to write their emails after receiving the intervention. Sharon’s numbers of words demonstrated big variations for both intervention phases. However, Sharon used more words in her emails than Mary did in hers. Sharon’s intellectual disability was milder than Mary’s, and she had better email-writing skills (as indicated by the baseline) before receiving the intervention. This could explain why Sharon used more words than Mary did in her emails after the intervention. Interestingly, this finding was not consistent with that of a prior study in which participants with lower pre-intervention performance showed more significant improvement post-intervention [10].

With respect to the total number of correct punctuations, both visual analysis of the data and Tau-U effect size calculations showed that participants’ numbers of correct punctuations increased. Before the intervention, Mary did not use any punctuation marks, and Sharon used just a few. Although big variations were found in the first and second intervention phases for both participants, they were able to use correct punctuations in response to the comments and feedback provided by ChatGPT. Similar to the findings for numbers of words, Sharon used a greater number of punctuation marks than Mary did. This may be attributed to Sharon’s higher rate of word usage, as frequency of punctuation often depends on overall word count.

While the total numbers of words written and correct punctuations written were not primary dependent variables, both revealed significant findings. The findings suggest that ChatGPT can help individuals to independently revise emails, using more words and punctuation marks to add clarity. Supporting individuals with intellectual disability in completing a task is a goal. Many studies have used strategies involving a combination of technology tools to help individuals with disabilities to complete a task independently (anonymized, 2023). It is common to see individuals with disabilities make mistakes when completing a writing task. These individuals frequently have a difficult time articulating their thoughts [6]. With proper prompts, ChatGPT can provide immediate feedback for users to help them correct their writing [18]. In the current study, participants were able to correct writing mistakes related to word usage, grammar, and punctuation. Although some of the final email drafts submitted by participants still had mistaken (e.g., Mary often forgot to add a period at the end of a sentence), most mistakes were addressed with the support of ChatGPT.

Although there are legitimate concerns about academic integrity and ChatGPT usage, it is important to note that the participants in this study first used the email checklist to draft their emails and then entered those emails into ChatGPT to check for issues of tone and grammatical, punctuation, and typographical errors. Before the participants sent out their emails to the interventionist, they were asked to check the emails’ overall appearance on the basis of the email-writing checklist. Participants also needed to provide both original and revised versions before they sent out their emails. Therefore, essentially, it was the participants who wrote their emails, not ChatGPT. Future writing instruction could consider incorporating ChatGPT. More writing interventions using ChatGPT should be developed and evaluated to determine their effectiveness in improving the writing skills of individuals with disabilities.

The current findings also extend research on using technology tools to improve the writing of individuals with disabilities [22,23]. The technology used in this study was an innovative, even revolutionary, AI tool. Currently, there is a dearth of email-writing interventions for individuals with intellectual disability, especially of ones using AI tools like ChatGPT. In addition, Thiel et al. [10] showed how difficulties with a writing-support software negatively influenced frequency of use, ultimately affecting users’ writing performance. Before conducting the current study, we were concerned that participants might find ChatGPT difficult to use. To our surprise, the participants in this study found ChatGPT easy to use. They had had no experience using ChatGPT before, but once they learned how to use it, they needed minimal support or guidance from the interventionist. The only issue we encountered during the intervention was occasional crashes of ChatGPT, which occurred when a large number of users were engaged with it simultaneously. Future research could explore ChatGPT-user experiences with individuals with disabilities so that an intervention with ChatGPT can be tailored to meet their needs [35].

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has several limitations. First, we only had two participants, both with intellectual disability. Future researchers should seek to field larger samples with different disabilities, such as autism. Second, although the results showed that our participants increased their email-writing skills, we could not be sure that they would apply what they had learned from the intervention to their email writing for work. Future researchers could explore email writing with individuals with disabilities and assess their continued utilization of technology tools like ChatGPT. Third, our email focus was limited to work-related scenarios, specifically five situations in which the writer was making a request. But email writing has various purposes, such as connecting with friends or sending invitations. Future researchers could implement an email-writing intervention with different scenarios while incorporating a technology tool like ChatGPT. Fourth, we did not realize how important prompts were and how they would affect users’ experiences. Since ChatGPT is still considered new in instructional arenas, we suggest that instructors and researchers try out a variety of prompts to find what will generate ideal responses and, thus, improve students’ learning. Testing of prompts will help users to provide clear instructions for ChatGPT-for example, offering more specific context, more steps, and better examples to guide the tool effectively. We suggest that future research use prompts such as “maintain the email content and list grammar check errors” or “maintain the email content and only provide a list of suggestions for improvement.” These types of prompts can generate lists of feedback for students, and students can then easily revise their email writing accordingly.

Conclusion

Research has shown that individuals with intellectual disability struggle with writing. There is presently a dearth of email-writing interventions for individuals with intellectual disability, especially interventions using AI tools like ChatGPT. The current study demonstrated that an email-writing intervention with an email checklist and ChatGPT has potential to improve email-writing skills for individuals with intellectual disability. Further research is needed to develop and evaluate email-writing interventions for these individuals.

Acknowledgement

Financial support for this study was provided by a grant from the Internal Research Award (INTRA) at the University of Texas at San Antonio. The authors wish to thank the award committee for finding great merit in this study.

References

- Heward WL, Alber-Morgan SR, Konrad M (2017) Exceptional children: An introduction to special education (11th edn). Pearson.

- Rodgers DB, Loveall SJ (2022) Writing interventions for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A meta-analysis. Remedial and Special Education 44(3): 239-252.

- Gargiulo RM, Bouck EC (2018) Special education in contemporary society: An introduction to exceptionality (6th edn). SAGE Publications.

- Geist L, Erickson K, Greer C, Hatch P (2020) Enhancing classroom-based communication instruction for students with significant disabilities and limited language. Exceptionality Education International 30(1): 42-54.

- Pennington R, Flick A, Smith-Wehr K (2016) The use of response prompting and frames for teaching sentence writing to students with moderate intellectual disability. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 33(3): 142-149.

- Rodgers DB, Datchuk SM, Rila AL (2021) Effects of a text-writing fluency intervention for postsecondary students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Exceptionality 29(4): 310-325.

- Sohlberg MM, Ehlhard, LA, Fickas S, Sutcliffe A (2003) A pilot study exploring electronic (or e-mail) mail in users with acquired cognitive-linguistic impairments. Brain Injury 17(7): 609-629.

- Sohlberg MM, Todis B, Fickas S, Ehlhardt L (2011) Analysis of e-mail produced by middle school students with disabilities using accessible interfaces: An exploratory study. Topics in Language Disorders 31(4): 352-372.

- Wang X-L, Eberhard D, Voron M, Bernas R (2016) Helping students with cognitive disabilities improve social writing skills through email modeling and scaffolding. Educational Studies 42(3): 252-268.

- Thiel L, Sage K, Conroy P (2017) Promoting linguistic complexity, greater message length and ease of engagement in email writing in people with aphasia: initial evidence from a study utilizing assistive writing software. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 52(1): 106-124.

- Yee K, Whittington K, Doggette E, Uttich L (2023) ChatGPT assignments to use in your classroom today. UCF Created OER Works (No. 8).

- Abdullah M, Madain A, Jararweh Y (2022) ChatGPT: Fundamentals, applications and social impacts. In 2022 Ninth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS). IEEE, pp. 1-8.

- Waltzer T, Cox RL, Heyman GD (2023) Testing the ability of teachers and students to differentiate between essays generated by ChatGPT and high school students. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. Article 1923981.

- Yorio K (2023) School librarians explore possibilities of ChatGPT. School Library Journal 69(2): 10-12.

- Arvidsson I, Leo U, Larsson A, Håkansson C, Persson R, Björk J (2019) Burnout among school teachers: Quantitative and qualitative results from a follow-up study in southern Sweden. BMC Public Health 19: Article 655.

- Walker M, Worth J, Van den Brande J (2019) Teacher workload survey 2019: Research report. UK Department for Education.

- Beck SW, Levine SR (2023) ChatGPT: A powerful technology tool for writing instruction. Phi Delta Kappan 105(1): 66-67.

- Baidoo-Anu D, Ansah OL (2023) Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. Journal of AI 7(1): 52-62.

- Su Y, Lin Y, Lai C (2023) Collaborating with ChatGPT in argumentative writing classrooms. Assessing Writing 57: 100752.

- Yan D (2023) Impact of ChatGPT on learners in a L2 writing practicum: An exploratory investigation. Education and Information Technologies 28: 13943-13967.

- Li J, Ren X, Jiang X, Chen CH (2023) Exploring the use of ChatGPT in Chinese language classrooms. International Journal of Chinese Language Teaching 4(3): 36-55.

- Pennington RC, Collins BC, Stenhoff DM, Turner K, Gunselman K (2014) Using simultaneous prompting and computer-assisted instruction to teach narrative writing skills to students with autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 49(3): 396-414.

- Woods-Groves S, Rodgers DB, Balint-Langel K, Hinzman-Ferris ML (2022) Efficacy of a combined electronic essay writing and editing strategy with postsecondary students with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 57(2): 177-195.

- Asaro-Saddler K (2014) Self-regulated strategy development: Effects on writers with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 49(1): 78-91.

- Asaro-Saddler K, Bak N (2012) Teaching children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders to write persuasive essays. Topics in Language Disorders 32(4): 361-378.

- Launder SM, Miller KM, Wood J (2022) Examining the impact of virtual procedural facilitator training on opinion writing of elementary school-age students with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 57(2): 216-228.

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D (2011) Using CBM for progress monitoring in written expression and spelling. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Student Progress Monitoring.

- Ledford JR, Gast DL (2018) Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences (3rd edn). Routledge.

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock JH, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, et al. (2013) Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial and Special Education 34(1): 26-38.

- Kazdin AE (2021) Research design in clinical psychology (5th edn). Cambridge University Press.

- Olive ML, Smith BW (2005) Effect size calculations and single subject designs. Educational Psychology 25(2-3): 313-324.

- Parker RI, Vannest KJ, Davis JL, Sauber SB (2011) Combining nonoverlap and trend analysis for single-case research: Tau-U Behavior Therapy 42(2): 284-299.

- Vannest KJ, Parker RI, Gonen O, Adiguzel T (2016) Single case research: Web based calculators for SCR analysis (Version 2.0) [Apparatus]. Texas A&M University.

- Vue G, Hall TE, Robinson K, Ganley P, Elizalde E, Graham S (2016) Informing understanding of young students’ writing challenges and opportunities: Insights from the development of a digital writing tool that supports students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly 39(2): 83-94.

- Rodgers DB, Datchuk SM, Wang L (2022) A paragraph text-writing intervention for adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Special Education Apprenticeship 11(2).