Lived Experience of Teachers in Teaching Students with Intellectual Disabilities in Burka Bekumsa Inclusive Primary School, Ethiopia

DinkaYadeta1 and Dawit Negassa2*

1Department of Special Needs and Inclusive Education, Ambo University, Ethiopia

2Department of Special Needs and Inclusive Education, Haramaya University, Ethiopia

Submission: February 20, 2022; Published: April 19, 2023

*Corresponding author: Dawit Negassa, Department of Special Needs and Inclusive Education, Haramaya University, Ethiopia.

How to cite this article: DinkaY, Dawit N. Lived Experience of Teachers in Teaching Students with Intellectual Disabilities in Burka Bekumsa Inclusive Primary School, Ethiopia. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2023; 11(4): 555818. DOI:10.19080/GJIDD.2023.11.555818

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore lived experience of teachers in teaching children with intellectual disabilities (CWID) in Burka Bekumsa Inclusive Primary School. A qualitative approach with phenomenological design was employed to obtain the required information from regular and special needs education (SNE) teachers. The study involved six teachers who were selected purposively for having experience of teaching CWID. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews and analyzed thematically. Findings of the study revealed that the education of CWID focuses on helping them acquire some basic daily life skills such as dining, personal hygiene, greetings and basic academic skills related to counting, self-awareness and environmental recognition which involve naming body parts, objects and animals. It was found that the educational experiences organized by the teachers and the school benefited the children in developing independent life skills, communication, behavior, relationships with typical children and teachers. The study also found that teachers’ skill of teaching and relationship with the CWID was improved successively as a result of familiarity with the behavior and ways of learning acquisition among CWID. Lack of relevant training for teachers on inclusion of CWID, shortage of classroom and appropriate educational materials, lack of incentives for teachers and weak parental involvement in the education of their children were identified as outstanding problems in educating the CWID. It is recommended that skill-related trainings and incentive packages should be organized for teachers to compensate for the demanding work, basic instructional resources should be allocated, and parents should be encouraged and empowered to take part in the education of their children.

Keywords: Children with intellectual disabilities; Ethiopia; Inclusive primary school; Lived experience

Introduction

Inclusive education is the process of responding to the diversity of children by enhancing participation in the classrooms and reducing exclusion from education [1]. Inclusive education ensures quality education for all students by effectively meeting their diverse needs in a responsive, respectful and supportive manner in mainstream educational settings. Mainstream schools include children with special educational needs in the classroom with their typical peers and seek to address the needs of all children by providing quality education. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 2006), states that every child has the right to education, irrespective of their disability and without any kind of discrimination. Therefore, children with special educational needs have the right to be educated in school settings that build their independence and sense of well-being with a view to facilitate maximum inclusion and active participation in their communities [2]. Historically, children with intellectual disabilities (CWID) are one of the groups of children with special educational needs who were denied the right to education in general and access to the mainstream neighborhood school in particular.

The American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities defines intellectual disability as a type disability that is characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, which cover several deficits in daily life skills. This disability originates before the age of 18 [3]. According to Turnbull & Wehmeyer [4] ID affects students intellectual and cognitive functioning, impairs social and adaptive behavior; affects language learning and use, and results in poor academic skills. Thus, the rate of learning new information may be very slow [5] and the children may require repetition, the use of concrete materials, and meaningful examples in all learning activities.

Research findings on the education of children with intellectual disabilities have shown that there are tested strategies in designing and organizing instruction for these children in an effective manner. For instance, Turnbull & Wehmeyer [4] indicated that the instructional delivery for CWID needs to be as concrete as possible. The topics and methods to be selected for teaching these children need to be tailored based on their intellectual capabilities and pace of learning [6]. King, Baxter, Rosenbaum, Zwaigenbaum & Bates [7] also noted that educating CWID requires teachers to use flexible approaches, relate the information to real life situation, and move from the known to the unknown. The authors further recommended that teachers should focus on few ideas in delivering lessons that involve complex topics and structure the tasks to be included in the learning process in order to encourage active participation of the students.

Along the same line, Emerson, Robertson, Baines & Hatton [8] indicated that the outlook of the teachers and the way they handle CWID play a vital role in the process of implementing educational programs designed for these children. The authors particularly underscored that teachers do not merely deliver the curriculum; instead, they have the potential to effectively contribute to defining, developing, and improving the whole educational process of students. Thus, for the successful implementation of inclusive education programs, enhancing teachers’ competence through initial teacher training and continuous professional development programs is vital [9].

A significant number of earlier studies conducted in many countries have shown that teachers have concerns about working with students with disabilities [10]. For example, a recent study conducted in Kenya showed that CWID were not taught effectively because teachers were not trained enough [11]. Other previous studies also showed that teachers lacked confidence for teaching in fully inclusive classrooms due to deficits in specialized skills and knowledge [12] and feel anxious when teaching in classrooms with diverse students [13].

Despite that inclusive education is being practiced in Ethiopia following the policy direction taken by the government of Ethiopia, the lived experience of teachers teaching CWID in inclusive schools is relatively a new area of study as it has not yet received a great deal of attention. Studies conducted in the area of intellectual disability focused on urban settings, mainly on topics related to parental experiences, attitudes of teachers and administrators, and practices and challenges faced by schools accommodating these children. The researchers were initiated to conduct the study by recognizing the paucity of research in inclusion of CWID in the county and by noticing practical problems experienced and complaints raised by teachers in the selected school while supervising university students assigned to the school for practicum.

Thus, the study aimed at answering the following research questions:

a) What is the nature of teaching children with intellectual disabilities from the teacher’s perspectives?

b) How do teachers describe their relationship with students with intellectual disabilities?

c) What were major challenges faced by the teachers in teaching students with intellectual disabilities?

Method

The qualitative approach was considered appropriate for this study because it provides an in-depth understanding and a rich description of the experiences of participants [14]. Phenomenological design, specifically transcendental phenomenology, was employed. This design is helpful when the aim of the study is describing the phenomenon using the participants’ experiences, perceptions, and voices. According to Creswell & Guetterman [15], in the transcendental phenomenology, what the study participants experienced are revealed through textural descriptions; whereas how the participants experienced the phenomenon is unveiled though structural descriptions.

Participants

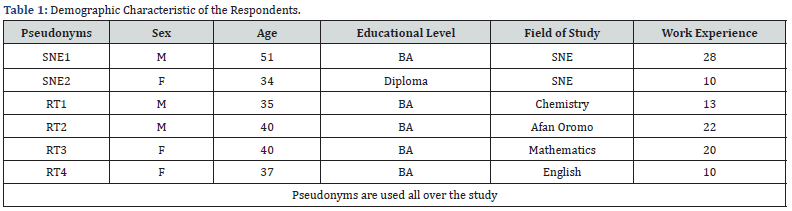

Participants of the study include 6 teachers of children with ID selected by using purposive sampling technique. Accordingly, 2 special needs education teachers and 4 subject teachers who have more than one year of experience in teaching CWID were selected.

Instrument

Semi-structured interview guide was used to obtain information on the lived experience of teachers teaching CWID. The interview included questions that focus on different areas such as demographic information, experiences on nature of teaching CWID, relationship with CWID and challenges encountered in teaching CWID. Probing questions were asked where necessary to obtain further information, clarify a point, or expand on ideas. Field notes on the experience of teachers were also made during each interview to check the trail.

Procedures

The participant teachers were contacted, and their consent issued three day before the interview session. Cooperative teacher was assigned to assist interview sessions with participants. Interview sessions were conducted in Afan Oromo; took 20- 30 minutes for each. Following the completion of all interview sessions, the interviews were transcribed and translated into English with utmost care. Finally, the data was coded, arranged and filtered into different themes intended for ultimate analysis.

Analysis

The study employed Moustakas [16] phenomenological model using phenomenological reduction. The researchers set aside their prejudgments and undertaken the research interview with an unbiased, receptive presence. After reading and rereading the transcribed interviews the researchers checked the originality or authenticity of the transcriptions and coded the transcripts. Then, important statements were clustered into categories and frequently emerging words or phrases used by the study participants helped in developing themes. Then, to reduce and come-up with overarching themes, comprehensive cross coding or merging of similar themes were carried out, and verbatim quotations were used to reveal the experiences of the participants by using their voices. Finally, the researchers have made reflections on the experience, combined description of the essence of phenomenon.

Ethical considerations

Participants were requested for their willingness to participate in the study by filling out a consent form prior to the interview sessions after description of the nature of the study. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, the researchers denoted the study participants by pseudonyms, and this was used throughout the study. Moreover, permission was sought and obtained for the interviews to be audio taped. The collected data was transcribed, translated, analyzed and reported with confidentiality and without revealing the identity of the study participants.

Results

Seven major themes were developed, which include: nature of education, benefit from inclusion, training sought, relationship with CWID, commitment, challenges and required improvement (Table 1).

Theme 1: Nature of education

According to the finding of the study, education of CWID mainly focuses on helping them to develop basic daily life skills like dining, personal hygiene, greetings, personal and environmental awareness. In academic areas, CWID learn basic numeracy and literacy skills counting, naming parts of the body, days of the week, household materials and objects in the surrounding environment. Teachers explained that in teaching these children, they use different materials and models to help them learn effectively.

In teaching CWID we use tangible materials to help them understand the issue (SNE1)

Always we write the day of the week on colorful a paper and post it on the door so that the students can read and recite (RT1)

I teach them how to hold tea cup, drink and eat appropriately. In addition, I teach them how to clean themselves after the meal (SNE2)

Respondents stated that vocational education is important but missing due to constraints of materials and resources.

There is no resource center and materials for equipping these children with vocational skills which are beneficial for the CWIDs (SNE1)

Theme 2: Benefits from inclusion

The teachers opined that the CWID were benefitted from the education and support provided by the school. Five teachers from the total six indicated that these students were benefited from the educational service provisions from the school. Accordingly, they explained that they observed improvement in the CWID in terms of behavior, communication, relationships with teachers and students, and learning.

Majority of CWID did not approach other students and teachers when they were admitted to school, but gradually they started to make connections with others (SNE1)

In addition to education we have school feeding program served during the break time. The school feeding program is used to attract the children to the school and we also use it to train CWIDs in basic life skills. Nowadays, I am observing that CWID are exhibiting improved skills in terms of personal hygiene and independent dining. I have also seen that some of them have shown advancements to the level of counting numbers (RT3)

Also, teachers mentioned that staying at school by itself is a big opportunity and it is a benefit for these children. Inclusion enabled the CWID to see the world outside of their home and enable them to grasp basic daily life skills and a little bit of academic knowledge. Moreover, it lessens the burden of parents by taking care of CWID at school.

What matters is not only the education and support they get from the school, but also the lessening of burdens imposed on families (SNE2).

However, one of the teachers was of the opinion that the CWID did not get benefit from the school and mentioned that their presence alone doesn’t guarantee that they are advantageous.

I do not see the expected change from students after they enrolled in this inclusive school (RT4)

Theme 3: Training

Two teachers have been trained in Special Needs Education (SNE) and taken the courses related to teaching CWID, whereas four teachers have taken only common courses during their preservice training. All the teachers, including those trained in SNE, revealed that they were not equipped with adequate knowledge and skills that enable them teach CWID.

I took only a common course when I attended the summer program. The course deals with many types of disabilities. So, I don’t feel that it enabled me to deliver the services expected of me (RT1).

During my BA study in Special Needs Education, I have taken many courses theoretically. But I was challenged to put them into practice. I think there is skill gap to address this group of students in inclusive school (SNE1)

Teachers also expressed the need for additional training for more practicality of endeavor. All the respondent teachers expressed their need for practical-oriented continuous in-service training. Moreover, all the remaining four subject teachers sought more in-depth training different from the one they have taken as a common course.

I need to have more detailed instruction on how to support CWID specifically. Also, it is better if the training is related to the subject I teach (i.e., Mathematics) (RT3)

Theme 4: Relationship with CWID

The study disclosed that teachers developed a positive relationship with CWID in the inclusive school. Except one regular teacher all the other respondent teachers stated that they have built good relationships with the children. The teachers reported that working with the children helped them become familiar and deliver lessons free from frustration.

In earlier times, when I hear about CWID from distance, I considered them as extremely violent and rebellious. But, after I came to know them, I removed such an attitude, and started approaching them with sympathetic feeling (SNE2).

When I enter their classroom or find them outside playing in the field, I call them by their names and I am delighted when they respond me appropriately. I am a mother with kids and my feeling towards these children is not only like a teacher, but similar to how I feel towards my own children (RT4).

From the perspective of the study participant teachers, the CWID exhibited improved relationship and trust towards their teachers. According to the respondent teachers, when the school initially started admitting them, the CWID had a tendency of keeping themselves away from people in the school including their teachers. But this was changed for the better, particularly the relationship CWID have with their teachers and typical students.

When we started practicing inclusion, CWID used to stay away from me. Even when I call their name, they used to keep silent. But now this has improved dramatically. What makes me surprised is that some students shared with me the disagreements they experienced with their parents and asked me for mediation. We negotiated and solved the conflicts (SNE1).

Theme 5: Teachers’ commitment

The study found that teachers’ dedication for their work is at risk due to lack of incentives and support and high workload. However, despite all the constraints, four of the respondent teachers mentioned that they were happy to work with CWID.

I enjoy my work; teachers have shouldered all kinds of burdens; the other stakeholders are not helping us and giving value for our contributions (SNE2).

Recently we are facing challenges to assign subject teachers to inclusive classrooms due to teachers’ lack of interest to work in inclusive classrooms due to high workload (RT1).

Theme 6: Challenges

In teaching CWID, the teacher respondents reported that they experienced challenges mainly related to high workload, shortage of trained special needs educators, lack of transportation for the CWID, low level of parental involvement, poor identification and assessment practices, lack of adequate classrooms and instructional materials, absence of vocational education, lack of appropriate training and lack of community ownership.

I spend much time with CWID teaching them how to take care of themselves, but no one considers my effort as valuable (SNE2).

We cannot teach students for the whole day because we have constraint of trained teachers to handle the classes. Also, parents do not follow-up what is going on in school with their students; they just bring them to school and take them home (RT2).

CWID could get more benefit from skill-based type of learning; unfortunately we do not have it due to lack of resources. Students who were identified to have special educational needs are not being supported by trained personnel (SNE1).

This inclusive school should own by community and different stake holders should be engaged, but practically missing from our school.

Theme 7: Required improvement

Respondent teachers mentioned the need for allocating adequate resources, incentivizing teachers, organizing relevant capacity building trainings for teachers, encouraging and empowering parents to take part in the education of their children, employing trained teachers and mobilizing resources for implementation of vocational education.

The school should be owned by the community including parents; the community alone cannot make the school inclusive (RT3).

The school has to seek resources to facilitate the school for CWID. Teachers need to be acknowledged for their work (SNE1).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the lived experience of teachers in teaching students with intellectual disabilities in Burka Bekumsa Inclusive Primary School. The study found that the essence of the lived experience of the participant teachers could be explained in seven major themes; namely, the nature of education for CWID, benefit from inclusion, training, relationship with CWID, teachers’ commitment, challenges and improvement required.

The results of the study identified education of SWID focuses on helping them to capture some basic daily life skills like eating, drinking, cleaning oneself, greetings and teaching fundamental knowledge related the like of number, days of the week, etc. In the teaching of student’s teachers explained, as they use different materials and models to help them to learn effectively. Similarly, studies support the focus education for SWID expected to enhance day-to-day living skills for these students. Living skills include various skill sets, which include walking style, eating style, handwriting, personal care, and taking care of personal belongings (Coyne et al., 2012). This is in line with Turnbull & Wehmeyer’s [4] suggestions to use concrete materials; provide the children with hands-on materials and real-life experiences, facilitate opportunities to try things out and focus on teaching life skills such as daily living skill, social skills, and occupational awareness and exploration, as appropriate and involving CWID in group activities.

The current study found that CWID were benefited from education and support from school and improvements were practically seen on the way they behave, learn, communicate and interact with typical children and teachers. In line with the finding from the present study, earlier literatures emphasized the benefit of inclusive education in academic performance, social interaction, behavioral outcomes, development in communication, and school attendance [10,17].

The present study identified teachers were developed a positive relationship with CWID in inclusive schools and reported that after working with these students, teachers become familiar with them, and students develop the same state of affairs. Creating familiarity with CWID contributed teachers to deliver what they have, and they can without fear. Studies also support teachers influenced by their SWID emotionally and socially and in another way, teachers may have influenced the students in different ways like academically and socially [18] In the same way study, another identified the existence of more positive attitudes, and more willingness to teach learners with intellectual disabilities among teachers [19]. Moreover, another support the role of close proximity of teachers appears to increase students’ social interaction [20]. This shows that the more teachers become familiar with SWID develop a tendency to know and accept them. The present study revealed challenges related to lack SNE trained human resource, lack of transportation to bring CWID to school and from school, poor family involvement, poor identification and assessment practice, lack adequate classrooms, missing vocational education, lack of appropriate training and lack community ownership. Supporting this finding, SWID were not taught effectively because teachers were not trained enough. Again, teacher training, staff development, and professional skills are core elements to developing schooling and improving teachers’ competence, especially for the inclusive education programs to be successful. This implies that training of teachers plays a pivotal role in inclusion of CWID. Another study also indicated that inclusion of CWID was impaired by teachers’ attitudes, teachers’ collaboration skills, the nature of the student’s disability, and the implementation of inclusive practices [21-24].

Also, the study identified poor parents’ involvement as one of the major factors affecting the inclusion of CWID. Regarding this, previous studies suggested that teachers are expected to work together with the parents and ensure collaboration with parents through regular contact and exchange of information about the status of the students at school and at home [4]. The teachers also expressed concern about the lack of vocational education in the school and its impact on CWID. Regarding this, existing literature suggest that education for CWID should mainly involve practical activities and vocational training [4].

Conclusion

The study concludes that education of CWID focuses on helping them to capture some basic daily life skills such as dining, personal hygiene, greetings and teaching basic academic skills like counting, naming days of the needs, lack of resources, lack of vocational training, lack of adequate classroom, lack of incentives for teachers and poor family involvement were identified as salient challenges in teaching week, self and environmental awareness. Good relationship of teachers with CWID has been improved with increased familiarity with each other.

Recommendation

It is recommended that emphasis should be given to provision of relevant training for teachers to offer appropriate education for CWID. Schools should work towards promoting community engagement including parents to realize inclusion of CWID. School has to mobilize and avail necessary resources to facilitate inclusion of CWID. Teachers should collaborate with the parents of students with ID to exchange information about the progress of CWID. The school has to find ways of providing incentives for teachers who are working with CWID. Other education stakeholders need to play their roles in supporting the school’s move toward practicing inclusive education much more by welcoming and addressing the needs of CWID within the regular classrooms.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Appendix - Semi-structured Interview Guide

I. Demographic information

A. Pseudo name __________

B. Gender __________

C. Age ___________

D. Educational level ____________

E. Field of study _________

F. Experience __________

II. Interview Questions

1. Tell me the education services/support provisions for CWID in your school.

2. How do you describe the focus of education for CWID? Adaptive and functional skills or common academic routines? Please explain!

3. Do you think CWID benefited by being admitted to an inclusive school and educated in an inclusive classroom? If yes, how? If not, why not?

4. How do you explain about your knowledge and skill in teaching CWIDs? How did you acquire the knowledge and skills you have about these children? If you have participated in some kind of training, by whom and for how long? Was it relevant and useful for your work?

5. What additional supports would have improved your educational experience with CWID? Include both academic and non-academic supports.

6. How do you describe your relationship with CWID? Fear/acceptance/proximity and the like.

7. As a teacher of CWID, is there a time when you felt giving up? Were you frustrated, were you angry? If so, tell me about these occasions or incidents.

8. Do you enjoy working with CWID? If yes, please explain. If not, why?

9. What are the challenges you encountered in working with CWID? What measures should be taken to overcome the challenges?

10. Finally, may I ask you to add if you have any additional experience with CWID?

References

- Ainscow M (2005) Understanding the development of inclusive education system.

- Hornby G (2015) Inclusive special education: development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. British Journal of Special Education 42(3): 234-256.

- Schalock RL, Borthwick-Duffy SA, Bradley VJ, Buntinx WH, Coulter DL, et al. (2010) Intellectual disability: Definition, classification, and systems of supports: ERIC.

- Turnbull R, Turnbull A, Wehmeyer ML (2007) Exceptional lives: Special education in today's schools (5th). Columbus, OH: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Burack JA, Evans DW, Russo N, Napoleon JS, Goldman KJ, et al. (2021) Developmental perspectives on the study of persons with intellectual disability. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 17: 339-363.

- Chatenoud C, Turcotte C, Aldama R (2020) Effects of three combined reading instruction devices on the reading achievement of adolescents with mild intellectual disability. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 55(4): 409-423.

- King G, Baxter D, Rosenbaum P, Zwaigenbaum L, Bates A (2009) Belief systems of families of children with autism spectrum disorders or Down syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 24(1): 50-64.

- Emerson E, Robertson J, Baines S, Hatton C (2014) The self-rated health of British adults with intellectual disability. Research in developmental disabilities 35(3): 591-596.

- Hughes C, Kaplan L, Bernstein R, Boykin M, Reilly C, et al. (2012) Increasing social interaction skills of secondary school students with autism and/or intellectual disability: A review of interventions. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 37(4): 288-307.

- Freeman SF, Alkin MC (2000) Academic and social attainments of children with mental retardation in general education and special education settings. Remedial and Special Education 21(1): 3-26.

- Yıldız G, Cavkaytar A (2020) Independent Living Needs of Young Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry 11(2).

- Florian L, Linklater H (2010) Preparing teachers for inclusive education: using inclusive pedagogy to enhance teaching and learning for all. Cambridge Journal of Education 40(4): 369-386.

- Sermier Dessemontet R, Morin D, Crocker AG (2014) Exploring the relations between in-service training, prior contacts and teachers’ attitudes towards persons with intellectual disability. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 61(1): 16-26.

- Creswell JW, Poth CN (2016) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches: Sage publications.

- Creswell JW, Guetterman TC (2019) Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Pearson.

- Moustakas C (1994) Phenomenological research methods: Sage publications.

- Dessemontet RS, Bless G, Morin D (2012) Effects of inclusion on the academic achievement and adaptive behaviour of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 56(6): 579-587.

- Nayereh Naghdi, Bagher ghobari (2017) Lived Experiences of Teachers of Students with Intellectual Disability: A Qualitative Phenomenological Study. Psychology of Exceptional Individuals, pp. 1-18.

- Ojok P, Wormnæs S (2013) Inclusion of pupils with intellectual disabilities: primary school teachers' attitudes and willingness in a rural area in Uganda. International Journal of Inclusive Education 17(9): 1003-1021.

- Carter EW, Lane KL, Cooney M, Weir K, Moss CK, et al. (2013) Parent assessments of self-determination importance and performance for students with autism or intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 118(1): 16-31.

- Abbass GM, Naghdi F (2020) The relationship between parenting style and family functioning with preschool children's behavioral problems. Management and Educational Perspective 2(1): 71-86.

- Bigby C, Anderson S, Cameron N (2018) Identifying conceptualizations and theories of change embedded in interventions to facilitate community participation for people with intellectual disability: A scoping review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31(2): 165-180.

- Kibria G (2005) Inclusion education and the developing countries: The Case of Bangladesh. Journal of the International Association of Special Education 6(1).

- Mazza MG, Rossetti A, Crespi G, Clerici M (2020) Prevalence of co‐occurring psychiatric disorders in adults and adolescents with intellectual disability: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 33(2): 126-138.