Quality Of Educational Interventions with Pupils with Special Needs, Perception of Disability and Self-Perceived Assessment Skills

Antonella Nuzzaci1*, Anna Murdaca2 and Marinella Muscarà2

1University of L’Aquila, Italy

2University of Enna Kore, Italy

Submission: February 25, 2022; Published: March 18, 2022

*Corresponding author: Antonella Nuzzaci, Department of Human Studies, University of L’Aquila, Italy

How to cite this article: Antonella N, Anna M, Marinella M. Quality Of Educational Interventions with Pupils with Special Needs, Perception of Disability and Self-Perceived Assessment Skills. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil, 2022; 9(5): 555774. DOI:10.19080/GJIDD.2022.09.555774

Abstract

The contribution addresses the relationship between educational interventions with pupils with special needs, perceptions of disability and self-perceived evaluation skills. Meeting the needs of pupils with intellectual disabilities requires the use of evidence-based educational practices, but also high-level evaluative skills. Assessment can be seen as a powerful tool to improve classroom instruction and outcomes for students with special needs. However, its effectiveness depends on the beliefs and skills of those who apply it on a daily basis in the classroom. This research aimed to investigate whether there was a significant relationship between the feelings, attitudes and concerns of teachers trained in inclusive education support and self-perceived assessment skills, and whether there were differences between those who feel more competent and those who feel less competent in terms of assessment and evaluation. The research shows that this relationship is present and that teachers who feel more competent about assessment and evaluation are also those who feel more concerned about how to meet the needs of students with special needs.

Keywords: Disability; Evaluation skills; Educational practices; Special needs; Students

Introduction

Meeting the needs of students with disabilities requires the use of evidence-based teaching practices, but also high-level assessment skills [1,2]. Assessment can be considered, in fact, a powerful tool to improve classroom education and the performance of pupils with special needs and plays a role in fully understanding their needs and strengths, especially through the monitoring of progress in learning, the use of assessment tools and the interpretation of data, with the aim of analyzing the actual effects of education proposals. However, the use of effective assessment depends on the attitudes, beliefs and skills of those who apply it daily in the classroom. One area that has been identified as vital for the continued development and success of inclusive educational practices is the initial and specialized teacher training [3,4]. Teachers need to acquire methodological skills and knowledge [5-7] to create inclusive environments and to remove negative attitudes and feelings to the benefit of positive ones regarding disability, thus allowing an inclusive future of pupils in their classrooms [8-11]. It is therefore important for future support teachers to maintain positive attitudes towards pupils with disabilities over time, subsequently ensuring the full functionality of inclusive education contexts. This is because these attitudes can be reflected on different aspects, which concern both the level of emotional reactions, cognitive and affective behaviors, and that of reactions towards disabled students [12].

Understanding teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion and disability can, therefore, be considered a fundamental first step in the design and evaluation processes of the teaching proposal aimed at students with special needs [13-16], since they can affect the quality of teaching, sometimes ending up compromising its outcomes. However, given the range of factors that can facilitate or hinder the assumption of positive or negative attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education and considering the role that evaluation assumes within the teaching-learning processes to determine the quality of the proposed interventions, studying the relationship, direct or indirect, that exists between these two components becomes essential because from the outset it may depend on the ability of teachers to feel or not able to meet the needs of pupils with special needs. The literature shows that teachers who report having had poor educational training feel less able to develop interventions directed at students with disabilities [17] and have a substantially weaker self-perception of evaluation skills, perceiving themselves less prepared to face classroom problems. It is known, in fact, how teachers feel in this kind of poorly prepared skills [1,2] and the responsibility for this preparation can only necessarily fall on those who are responsible for preparing programs, initial and in service, aimed at their formation. To meet the range of needs commonly associated with the needs of learners, support and curricular teachers must therefore be prepared to provide “specialized support” and appropriate responses to sometimes very challenging behaviors [18] in terms of complexity [19,20], but above all to use appropriate and metrologically correct evaluation techniques and tools [1] to determine the quality of the interventions prepared.

Teachers, in fact, frequently use a variety of forms of assessment at school and the training experience explains some variations related to the characteristics of the teaching practices adopted. This relationship, however, is not always direct, due to the multiplicity of variables at stake [13]. Among the factors, which more than others, are responsible for the implementation of the success of inclusive education we find precisely the attitudes of teachers, which become central to overcoming perceptual difficulties, to deconstruct misconceptions and to remove common senses about teaching-learning processes, as well as to fulfill the needs of all students with difficulties, also resorting to strategies of personalization and individualization and dispensative support and compensatory, where necessary [21].

The implementation of these changes requires, then, to focus, in the training, in the first place, on professional skills [22,23], and, among these, the evaluation and assessment ones appear decisive for understanding the validity of the educational interventions carried out. Let’s think about how these kinds of skills affect, for example, the ability to adapt, differentiate, accommodate or modify teaching strategies and prepare, implement or evaluate personalized interventions in an attempt to develop adequate teaching-learning processes [24,25], which presuppose the possession of scientifically based attitudes and beliefs that guide action.

In the literature it is now believed, in a fairly shared way, that the practice of teachers can strongly depend on beliefs and attitudes regarding education, learning and teaching, which strongly determine the choice or not to promote new assessment practices. Bliem e Davinroy [26] stressed the importance of teachers’ perceptions of the ability to “measure” learning as key dimensions of likely success in teaching, which would act as an interpretative lens through which to read information about class practices and which could facilitate or hinder any actions that interfere with beliefs, attitudes and competences.

It is therefore reasonable to assume that the way in which teachers implement or not new forms of assessment and assessment in educational contexts, where the didactic proposal is directed to special needs, will therefore depend, to a large extent, also on their attitudes towards children with disabilities and on their feelings and concerns about inclusive education, who are to be considered significant predictors of their intentions to promote or not the full inclusion of children within the classroom, which cannot be achieved without evaluative skills that enable them to implement successful inclusive practices [27] and to support the learning of students with special needs, helping them to fit into an environment suited to their needs [28,29].

Therefore, deconstructing the negative attitudes of teachers in the phase of specialized initial training on support can serve to equip them with those interpretative tools that enable them to understand and govern the teaching processes [30], ensuring all students the same opportunities and full participation in an inclusive school culture. Considering that teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion vary greatly with the variation of pupils with special needs and that they predict the effective adoption of inclusive behaviours within the classroom [14,16], it is important to be able to measure them in such a way as to identify and address any obstacles to the proper implementation of inclusive training and education policies. This aspect is highlighted by all that educational research that highlights how attitudes have a significant impact also on the learning environment of students [15,16] with different types and levels of disability [31].

Methodology

Research design

Research explores the relationship between teachers’ attitudes, concerns and feelings in relation to disability [32] and self-perceived teacher evaluation skills [33] in initial specialized training, trying to understand whether or not these aspects are related and if they are in what way. In Italy, the Specialization Courses of Special Education Teachers have been established starting from ministerial decree no. 249 of 10/09/2010, containing the regulation concerning: “Definition of the discipline of the requirements and methods of initial training of teachers of primary school and secondary school of first and second degree, pursuant to art. 2, paragraph 416, of Law no. 244 of 24/12/2007” and by the Ministerial Decree of 30 September 2011 “Criteria and procedures for carrying out training courses for the achievement of specialization for support activities, pursuant to articles 5 and 13 of Decree 10 September 2010, n. 249” (G.U. n. 78 of 2.4.2012) and Legislative Decree no. 59 of 13 April 2017 (implementing decree of Law no. 107 of 13 July 2015) “Reorganization, adaptation and simplification of the system of initial training and access to the roles of teacher in secondary school to make it functional to the social and cultural enhancement of the profession, pursuant to Article 1, paragraphs 180 and 181, letter b), of the law of 13 July 2015, No 107”. This research refers to the students enrolled in the specialization courses for educational support to students with disabilities in the academic year 2020-2021 in the Sicily Region.

A descriptive and correlational research method was used in the study, using two types of data collection tools:

1. SCVA (Scala delle Competenze Valutative e di Assessment Auto-percepite / Scale of Self-Perceived Evaluation and Assessment Skills) [33], designed to measure teachers’ self-perceived assessment skills, which consists of 39 items, the inventory of which has been developed within the theoretical framework outlined by the evaluation literature [34-37]. It is a four-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all skillful) to 4 (very skillful), and is composed of nine factors: F1 (Perceived ability about the principles of evaluation); F4 (Perceived ability to use assessment); F2 (Perceived ability in the use of assessment tools); F3 (Perceived ability related to evaluation with respect to the improvement of learning and results); F5 (Perceived ability in communicating the results of the evaluation); F6 (Perceived ability in the validity of instruments); F7 (Perceived ability to use criteria); F8 (Perceived ability in measurement); F9 (Perceived ability to use feedback). To ensure the validity of the content of the instrument, transcription tables were used to evaluate the items of the scale and both external evaluators and teachers were engaged to verify the correspondence between the items of the test and the individual aspects contained in it, providing reviews based on the feedback received and the analysis of the items [38,39]. The instrument was subjected to try out and then validated with teachers in initial training and in service, reaching, very high psychometric qualities and a Cronbach Alpha of α = .986.

2. SACIE-R (Sentiments, Attitudes and Concerns about Inclusive Education Revised) is a scale consisting of 15 items grouped into three factors. The first factor (Feelings) evaluates feelings in interaction or contact with students with disabilities; the second factor (Attitudes) focuses on the acceptance of students with disabilities; the third factor (Concerns) assesses concerns about inclusive education. The ladder was used with teachers in service and in training [19,40,41] and has adequate psychometric properties, providing an adequate measure of teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of teachers in training and in service. Of the three dimensions, in all national and international validations, the “Concerns” factor is more significant and has always presented the best reliability indices compared to the other dimensions [19,40,41]. The validity results show good factor structure indices [19] and seemed to justify the internal validity of the instrument in the different samples.

Hypothesis

Hp1 = There is a significant relationship between attitudes, feelings and concerns of teachers in training on support towards inclusive education and self-perceived evaluative skills.

Hp2 = There are significant differences in feelings/opinions, attitudes and concerns towards disability between those who feel more competent and those who feel less competent in terms of assessment and assessment.

Analysis of Results and Discussion

The SPSS version 21 statistical package was used to carry out the data analysis. The participants in the study were teachers in training attending the Course for special education teachers in the Sicilian area. There were 965 respondents, of which 16.4% were male and 83.5% female, reconfirming how teaching continues to be a predominantly female profession, also in the context of support.

The age of the participants in the sample varies between 23 and 60 years of age with an average of 39.41: 27.15% between 23 and 34 years, 50.46% between 35 and 46 years and 38.0% between 47 and 60 years.

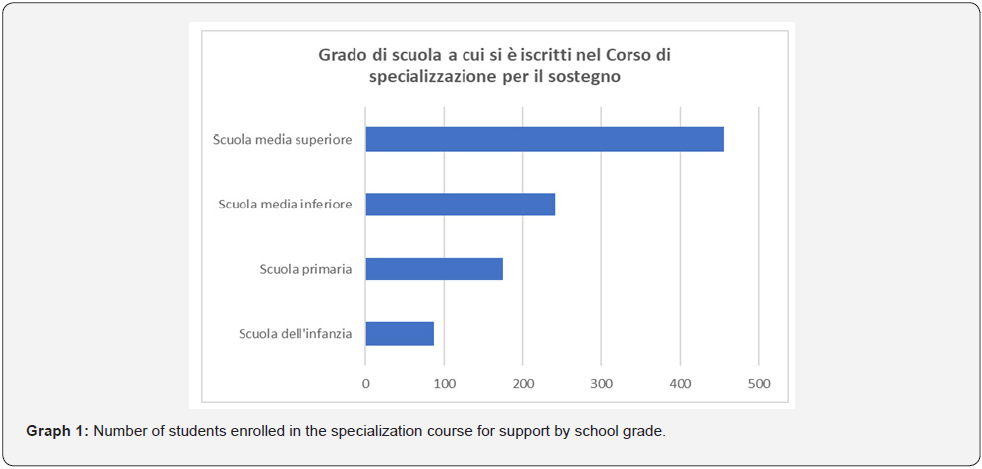

The sample is composed of teachers or aspiring teachers of all levels of school from all the Sicilian provinces, particularly from Catania, Messina, Agrigento, Caltanissetta and Enna. The largest percentage of the sample is enrolled in the Specialization Course for support in secondary school (47.5%), followed by lower secondary school (25.2%), primary school (18.2%) and kindergarten (9.1%).

The number of years of service performed, including the current year, pre-role or in another role, varies from 0 to 44, with an average of 3.96 years (n = 946). 71.8% of the sample declares to have had, until the time of the interview, at least one teaching assignment, while the remaining part (28.2%) say they have never done any. From the point of view of the qualification, the sample has extremely heterogeneous characteristics in terms of training and origin (Graph 1).

The exploration conducted on the variables of age, sex, occupation, years of service and school grade shows how the association between role/non-role and years of service affect perceptions of evaluative skills and the concern of not having sufficient skills to meet the needs of pupils with special needs, exploration that would deserve further study.

To answer the first hypothesis, the correlational analysis between the two Scales (SACIE-R and SCVA) was carried out, also with inversion of the scores for the SACIE-R scale of those elements associated with the factors related to the discomfort experienced in the interaction with disabled people and fear of having a disability. Negatively worded items were reverse-coded before calculating scale indices before studying the relationship between SACIE-R and SCVA.

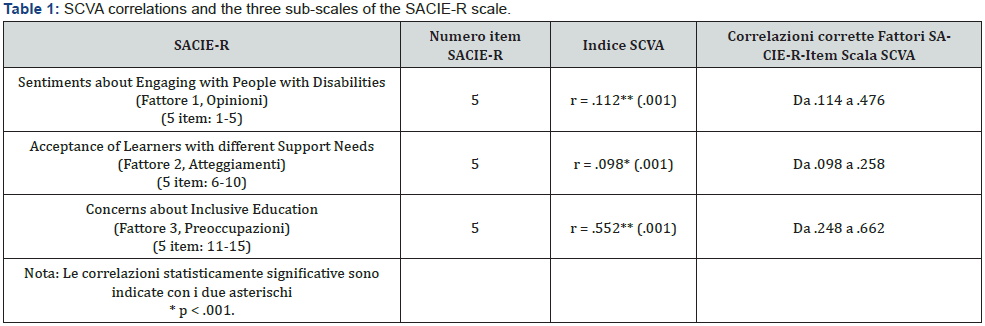

The comparison shows, also through the creation of the synthetic indices, obtained from the two scales, how, in the sample studied, there tends to be a significant positive correlation between the indices of the two scales, but how this correlation becomes more significant between Factor 3 (Concerns) of SACIE-R and the Factors of SCVA: F2 (Ability perceived in the evaluation tools), F8 (Perceived Ability in Measurement) and F9 (Perceived Ability in Using Feedback). SacIE-R Factor 3 (Concerns) has a stronger correlation with SCVA than Factor 1 “Feelings/Opinions” and Factor 2 “Attitudes”. Factor 3 (Concerns) is correlated with the index of the SCVA scale (r = .552) and, the latter, specifically, with item number 15 of SACIE-R – “I am concerned that I do not have the knowledge and skills necessary to meet the needs of children with special needs” – (r = .679). SACIE-R shows that it is more related to the following SCVA Factors: F2 (Ability to use measuring instruments) (r = .658**), F8 (Ability to measure) (r = .662**) and F9 (Perceived ability to use feedback) (r = .632**), testifying to the fact that there is a relationship between measurement skills and concern about not being able to meet the needs of pupils with special needs and how such concerns are related to positive or negative attitudes towards disability and self-perception of skills for creating inclusive school contexts (r = .512). The items of factor 3-SACIE-R “I am concerned that, if I have disabled students in my class, the workload will increase” (item 11 (r = .432**) and “I am concerned that, with disabled students in my class, I will be more stressed” (item 13 (r = .478**) are also related to SCVA respectively.

Compared to the first hypothesis (Hp1), it can be said that there is a significant relationship between attitudes, feelings and concerns of teachers in training on support towards inclusive education and self-perceived evaluative skills, since the correlations are non-zero and in the expected direction, even if the link between concerns and evaluative attitudes and competences is stronger than the relationship that binds the latter to feelings. Further insights into the relationship between attitudes and evaluative skills revealed how this relationship is mediated by other variables (Table 1).

To answer the second hypothesis that there is a statistically significant difference in the averages of different groups, the sample was divided into teachers with low and high perception of competence in terms of evaluation. This is in order to explore whether there were differences between those who feel they possess “poor” or “high” assessment skills with respect to factors opinions, attitudes and concerns towards inclusive education, but above all with respect to the latter. Regarding the variables related to the interactions within the group, it can be observed that the participants who feel they have “poor” evaluation skills are less worried about not having the necessary skills to meet the needs of students with special needs than the “high perception” group. From the post-hoc it emerges that there is a significant difference between the first group and the second group with an effect of the low/high perception variable in the SCAV evaluation skills in relation to the SACIE-R-Concerns Factor, but above all with respect to the item “I am concerned about the fact that I do not have the necessary knowledge and skills” concerning low perception (F(13,2) = 3,888, p =.01) and high perception (F(14,1) = 4,987, p =.002) and the item “I am concerned that with disabled students in my class my workload will increase” in reference to the “low” (F(13) = 2,988, p =.01) and the “high” perception (F(14) = 3,686, p =.002).

A series of subsequent post hoc checks also highlights how the high perception of competence in the evaluation is related to the importance of following refresher courses both in disability (r = .274) and in evaluation (r = .305), testifying to the action that plays awareness in those who feel more competent. In addition, the low and high perception in the evaluative skills and those with high evaluative skills with respect to the item that expresses the concern for not having knowledge and skills indispensable to meet the needs of students with special needs and concern (but with inverse correlation trend) for the fact of having disabled students in the class that will increase the amount of work (item 11 Factor 3-SACIE-R) and the concern that, with disabled students in my class, stress will increase (item 13 Factor 3-SACIE-R). The goodness of this interpretation is supported by the significant correlation between factor 2-SACIE-R (Attitudes) (positive items) and those who have higher competence in terms of evaluation skills.

The second hypothesis (Hp2) is also confirmed, as the results revealed that the Between Variance/Within Variance ratio is large enough to confirm the hypothesis that the averages between the two groups are different and that future teachers with perceptions of higher evaluative competence have greater concern about not being able to have the knowledge and skills to meet the needs of pupils with disabilities. The ANOVA that allowed to compare teachers with higher perception of competence in evaluation and teachers with lower perception highlighted how the former showed greater awareness towards inclusive education, confirmed by the significant positive correlation between Factor 2-SACIE-R and SCAV (r = 338). These findings are in line with a whole range of studies showing that teachers following appropriate training show an increase in concerns about all aspects of the inclusion of students with disabilities and feeling able to best meet their training needs and who perceive themselves as unprepared for inclusive education [31], judging in 98.8% important or very important the training linked to the satisfaction of children with special needs [42]. As the literature explains, training in the field of special education seems to improve attitudes towards inclusion [43] and increase concerns about inclusive education.

This aspect is also supported by the correlational analysis that has shown, tendentially, how the years of service / role of teachers in training on support is related to the SACIE-R “Concern” Factor (r = .398) and to the concern of teachers of not being able to meet the needs of students with special needs and who do not have the knowledge and skills necessary to teach students with disabilities (r = .558) and feel less able to cope with interactions with people with disabilities (r = .427). In addition, it is highlighted that the self-perception of the evaluative competences of teachers in support training is associated with the role (role / non-role) and the importance that the subjects attribute to updating / training related to the training needs of students with special needs, as well as the concern that they do not have the knowledge and skills necessary to teach students with disabilities (but the regression analysis in this context is not object of attention). The very high correlation between the variable “Indicate how important you consider to attend refresher / training courses related to the training needs of students with special needs” and “Indicate how important you consider to attend refresher / training courses focused on the problems of school evaluation” (r = 837 **) goes in support of the interpretation that it is higher where it is considered more important training related to students with special needs and that relating to evaluation [44-50].

Conclusions, implications and limitations of the study

This first study, despite bringing out important results, still has some limitations that must be taken into due consideration in the interpretation. First, the research was based on data from a non-probabilistic sample of two Sicilian universities and further insights are needed to confirm the solidity of the results obtained, employing other sampling methods and studying the incidence of other variables, directly or indirectly related to feelings, attitudes and concerns towards disability, for a better understanding of the relationships and influences that bind them to the self-perception of evaluative skills, but above all to the role that personal concerns play, since, although the analysis has included correlational analysis and the construction of the indices obtained from the two scales, the latter two in the examination of variables and in the validation of hypotheses appear in correlations to follow a recursive trend, which needs to be further explored in the causal relationships of variables if we want to put at the center of the training of support teachers those evaluative skills necessary for the management of teaching-learning processes that affect students with special needs, long too neglected in this area [51- 62].

References

- Nuzzaci A (2019a) Credenze, atteggiamenti e percezioni verso la valutazione dei futuri insegnanti di scuola dell’infanzia e di scuola primaria. In P Lucisano, AM Notti (a cura di), Training actions and evaluation processes Atti del Convegno Internazionale SIRD. Lecce-Brescia: Pensa MultiMedia Editore s.r.l, pp. 573-587.

- Nuzzaci A (2019b) Valutare che fatica! L’evaluation e l’assessment come competenze metodologiche della professione insegnante. Nuova Secondaria Ricerca (Atti della III Conferenza bergamasca - Formazione e sviluppo professionale del docente. Modelli, pratiche, sistemi a confronto) 36(10): 38-44.

- Loreman T, Deppeler J, Harvey D (2005) Inclusive education: a practical guide to supporting diversity in the classroom. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

- Loreman T, Deppeler J, Harvey D, Rowley G (2006) The implications of inclusion through curriculum modification for secondary school teacher training in Victoria, Australia. International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations 4: 1183-1197.

- Nuzzaci A (2016) Editorial - Science of teaching, training and methodological skills of teachers and trainers: from design to evaluation - Scienza dell’insegnamento, formazione e competenze metodologiche degli insegnanti e dei formatori: dalla progettazione alla valutazione. Formazione & Insegnamento. European Journal of Research on Education and Teaching 14(3): 9-14.

- Nuzzaci A (2020a) Beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions towards evaluation and assessment of future primary school teachers: the role of the previous scholastic experience. Pro Edu. International Journal of Educational Sciences 2(3): 5-20.

- Nuzzaci A, Altomari N, De Pietro O, Valenti A (2020b) The self-perceived skills of teachers in initial training: validation of a scale to measure methodological skills. Lifelong Life wide Learning 16(35): 338-353.

- D’Alonzo L (2017) Motivare i demotivati a scuola. Brescia: La Scuola.

- Cottini L (2011) L’autismo a scuola: quattro parole chiave per l’integrazione. Roma: Carocci.

- Avramidis E, Bayliss P, Burden R (2000) A survey into mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school in one local education authority. Educational Psychology 20(2): 191-195.

- Avramidis E, Norwich B (2002) Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion a review of the Literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education 17(2): 129-147.

- Nowicki EA, Sandieson R (2002) A meta-analysis of school-age children’s attitudes towards persons with physical or intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 49(3): 243-265.

- Antonak RF, Livneh H (2000) Measurement of attitudes towards persons with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation 22(5): 211-224.

- MacFarlane K, Woolfson LM (2013) Teacher attitudes and behavior toward the inclusion of children with social, emotional and behavioral difficulties in mainstream schools: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Teaching and Teacher Education 29(1): 46-52.

- Monsen JJ, Frederickson N (2004) Teachers’ attitudes towards mainstreaming and their pupils’ perceptions of their classroom learning environment. Learning Environments Research 7(2): 129-142.

- Monsen JJ, Ewing DL, Kwoka M (2014) Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion, perceived adequacy of support and classroom learning environment. Learning Environments Research 17(1): 113-126.

- Breton W (2010) Special education paraprofessionals: perceptions of pre‐service preparation, supervision, and ongoing developmental training. International Journal of Special Education 25(1): 34-45.

- Muscarà M (2018) Scuola inclusiva e insegnante di sostegno. La specializzazione come componente essenziale della formazione iniziale dei docenti. Lecce-Brescia: Pensa MultiMedia.

- Murdaca AM (2008) Complessità della persona e disabilità. Le nuove frontiere culturali dell'integrazione. Pisa: Edizioni del Cerro.

- Muscarà M, Messina R (2014) Motivazione e percezione dell’importanza delle competenze psico-pedagogiche e didattiche della professionalità docente tra gli aspiranti insegnanti iscritti ai percorsi abilitanti speciali (PAS): uno studio esplorativo. I problemi della pedagogia 1: 55-73.

- Janney RE, Snell ME (2006) Modifying schoolwork in inclusive classrooms. Theory Into Practice 45(3): 215-223.

- De Boer A, Pijl SJ, Minnaert A (2011) Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education 15(33): 331-353.

- Poon-McBrayer KF, Wong PM (2013) Inclusive education services for children and youth with disabilities: Values, roles and challenges of school leaders. Children and Youth Services Review 35(9): 1520-1525.

- Fisher D, Frey N, Thousand J (2003) What do special educators need to know and be prepared to do for inclusive schooling to work? Teacher Education and Special Education. The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children 26(1): 42-50.

- Subban P (2006) Differentiated instruction: a research basis. International Education Journal 7(7): 935-947.

- Bliem C, Davinroy K (1997) Teachers’ beliefs about assessment and instruction in literacy. Center for the Study of Evaluation, National Centre for Research on Evaluation, Standards and Student Testing, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

- Johnstone CJ, Chapman DW (2009) Contributions and Constraints to the Implementation of Inclusive Education in Lesotho. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 56(2): 131-148.

- Purdue K, Gordon-Burns D, Gunn A, Madden B, Surtees N (2009) Supporting inclusion in early childhood settings: some possibilities and problems for teacher education. International Journal of Inclusive Education 13(8): 805-815.

- Blecker NS, Boakes NJ (2010) Creating a learning environment for all children: are teachers able and willing? International Journal of Inclusive Education 14(5): 435-447.

- Singal N (2010) Doing disability research in a Southern context: challenges and possibilities. Disability & Society 25(4): 415-426.

- Forlin C, Chambers D (2011) Teacher preparation for inclusive education: increasing knowledge but raising concerns. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 39(1): 17-32.

- Murdaca AM, Oliva P, Costa S (2016) Evaluating the perception of disability and the inclusive education of teachers: the Italian validation of the Sacie-R (Sentiments, Attitudes, and Concerns about Inclusive Education – Revised Scale), European Journal of Special Needs Education 33: 148-156.

- Nuzzaci A (2018) Quale valutazione nelle credenze, negli atteggiamenti e nelle percezioni dei futuri insegnanti di scuola dell’infanzia e di scuola primaria. In S. Ulivieri (a cura di), Le emergenze educative della società contemporanea. Progetti e proposte per il cambiamento (pp. 385-394). Lecce-Brescia: Pensa MultiMedia Editore s.r.l.

- Airasian P (1994) Classroom Assessment. 2nd Edition, McGraw Hill, New York.

- Carey A (1994) The group effect in focus groups: Planning, implementing and interpreting focus group research. In: Morse, J. M., Ed., Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks. pp. 225-241.

- William D Schafer (1991) Validity and Inference: A Reaction to the Unificationist Perspective. 69(6): 558-560.

- Richard J Stiggins (1991) Relevant Classroom Assessment Training for Teachers. Educational Measurements 10(1): 7-12.

- Zhang Z, Burry-Stock JA (1994) Assessment practices inventory. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama.

- Zhang Z, Burry-Stock JA (2003) Classroom assessment practices and teachers’ self-perceived assessment skills. Applied Measurement in Education 16: 323-342.

- Forlin C, Earle C Loreman T, Sharma U (2011) The sentiments, attitudes and concerns about inclusive education revised (SACIE-R) Scale for measuring pre-service teachers’ perceptions about inclusion. Exceptionality Education International 21(2-3): 50-65.

- Cansiz N, Cansiz M (2018) The validity and reliability study of Turkish version of the sentiments, attitudes, and concerns about inclusive education scale. Kastamonu Education Journal 26(2): 271-280.

- Van Reusen AK, Shoho AR, Barker KS (2001) High school teacher attitudes toward inclusion. High School Journal: 84: 7-21.

- Powers S (2002) From concepts to practice in deaf education. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 7(3): 230-243.

- Bender WN, Vail CO, Scott K (1995) Teachers’ attitudes toward increased mainstreaming: implementing effective instruction for students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities 28(4): 87-94.

- Briggs JD, Johnson WE, Shepherd DL, Sedbrook SR (2002) Teacher attitudes and attitudes concerning disabilities. Academic Exchange Quarterly 6(2): 85-90.

- Brock ME, Carter EW (2013) A systematic review of paraprofessional‐delivered educational practices to improve outcomes for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 38(4): 211-221.

- Cook BG, Smith GJ, Tankersley M (2012) Evidence‐based practices in education. In: KR Harris, S Graham, T Urdan (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, Vol 1, pp. 495-528.

- Daane CJ, Beirne-Smith M, Latham D (2000) Administrators’ and teachers’ perceptions of the collaborative efforts of inclusion in the elementary grades. Education 121(2): 331-339.

- Day C, Sammons P, Hopkins D, Harris A, Leithwood K, et al. (2009) The impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes. Final Report. DCSF Research Report RR108. Nottingham: University of Nottingham.

- Forlin C (2010) Re-framing teacher education for inclusion. In: C Forlin (Ed.), Teacher Education for Inclusion: Changing Paradigms and Innovative Approaches. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 3-10.

- Forlin C, Jobling A, Carroll A (2001) Pre-service teachers’ discomfort levels toward people with disabilities. Journal of International Special Needs Education 4: 32-38.

- Monsen JJ, Ewing DL, Boyle J (2015) Psychometric properties of the revised teachers’ attitude toward inclusion scale. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 3(1): 64-71.

- Nuzzaci A (2016) Promoting and supporting the methodological skills of teachers and trainers for the successful of the teaching and the quality of the training / Formazione & Insegnamento. European Journal of Research on Education and Teaching 14(3): 17-36.

- Nuzzaci A, Murdaca AM, Muscarà M (in press). Usare la valutazione per accrescere la qualità degli interventi didattici con allievi con bisogni speciali: competenze valutative auto-percepite e percezione della disabilità / Using assessment to increase the quality of educational interventions with pupils with special needs: self-perceived assessment skills and perception of disability. In Convegno internazionale SIRD 2021 - Quale scuola per i cittadini del mondo. A cento anni dalla fondazione della Ligue Internationale de l’Éducation Nouvelle, Salerno, Roma, 25-26 novembre 2021.

- Schmidt M, Vrhovnik K (2015) Attitudes of teachers towards the inclusion of children with special needs in primary and secondary schools. Hrvatska Revija Za Rehabilitacijska Istrazivanja 51(2): 16-30.

- Schafer WD (1991) Essential assessment skills in professional education of teachers. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 10(1): 3-6.

- Schumm JS, Vaughn S (1991) Making adaptations for mainstreamed students: regular classroom teachers’ perspectives. Remedial and Special Education 12(4): 18-27.

- Schumm JS, Vaughn S (1992) Planned for mainstreamed special education students: perceptions of general education teachers. Exceptionality 3(2): 81-98.

- Schumm JS, Vaughn S, Gordon J, Rothlein L (1994) General education teachers’ beliefs, skills, and practices in planning for mainstreamed students with learning disabilities. Teacher Education and Special Education 17(1): 22-37.

- Schumm JS, Vaughn S, Haager D, McDowell J, Rothlein L, et al. (1995) General education teacher planning: what can students with learning disabilities expect? Exceptional Children 61(4): 335-352.

- Sharma U, Forlin C, Loreman T, Earle C (2006) Pre-service teachers' attitudes, concerns and sentiments about inclusive education: an international comparison of novice pre-service teachers. International Journal of Special Education 21(2): 80-93.

- Tobin R, Tippett C (2014) Possibilities and potential barriers: learning to plan for differentiated instruction in elementary science. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 12(2): 423-443.