Caregiver Voices: Initial Impact of COVID-19 on Family Caregivers of Children with and Without Developmental Disabilities

Emily A Iovino*, Hannah Y Perry, Sandra M Chafouleas and Alyssa Bunyea

Department of Educational Psychology, Neag School of Education, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States

Submission: July 15, 2021; Published: July 26, 2021

*Corresponding author: Emily A Iovino, Department of Educational Psychology, Neag School of Education, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States

How to cite this article: Iovino E A, Perry H Y, Chafouleas S M, Bunyea A. Caregiver Voices: Initial Impact of COVID-19 on Family Caregivers of Children with and Without Developmental Disabilities. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil, 2021; 8(5): 555748. DOI:10.19080/GJIDD.2021.08.555748

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an unprecedented impact for children and families. Initial findings suggest alarming concerns for caregivers of school-age children as a result of the pandemic, which may be even greater for caregivers of children with developmental disabilities (DD) given challenges faced in typical circumstances. As such, the purpose of this study was to explore the impact of COVID-19 on the personal well-being of caregivers of children with and without DD and define the needs of these caregivers during a global pandemic. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with caregivers of children with DD (n = 13) and caregivers of children without DD (n = 17) between May 2020 and June 2020. Results of these interviews are consistent with initial reports, suggesting that all caregivers have been struggling to varying degrees throughout the pandemic, with caregivers of children with DD reporting greater challenges with regard to stress and their personal well-being, in addition to greater challenges with supporting their child(ren)’s educational needs. Considerations are presented for best supporting families of school aged children amid a pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19; Family caregivers; Children; Developmental disabilities

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on families. As the novel virus spread across the United States in early 2020, schools in all 50 states closed while the workforce faced remote business operations, layoffs, and reduced hours [1-4]. Family life was changed drastically, particularly for caregivers of school-age children tasked with managing their child’s education from home [1,2]. Family caregivers have faced balancing of multiple roles and responsibilities, with many acting as a parent/guardian, teacher, spouse, and employee/employer [2,3]. More than one third of working parents in the U.S. reported struggling to balance their work obligations and childcare responsibilities during the pandemic [5].

Preliminary reports suggest that caregivers of children are experiencing elevated stress, poorer mental health, and financial hardships due to COVID-19 [1,2,6]. In one study on parenting stress during COVID-19, over half of parents indicated that financial concerns and worries “sometimes” or “often” got in the way of their parenting; parents also reported that social isolation (50%), sadness (35%), and loneliness (27%) negatively impacted their parenting “sometimes” or “often” [7]. Additional findings from a March 2020 survey indicated about a 70% increase in the number of parents reporting feeling anxious or depressed, with two thirds of families reporting reduced income during the pandemic [8]. Another recent survey of parents living in the Western U.S. found associations between their perceived stress and COVID-19-related changes (e.g., loss of employment, school closures, transition to remote working, stay-at-home orders) [9]. Initial findings during COVID-19 suggest alarming concerns for all caregivers, which may be even more alarming for caregivers of children with developmental disabilities (DD) given challenges faced in typical circumstances [2,10]. Prior to COVID-19, caregivers of children with DD have demonstrated challenges with maintaining health and well-being due to chronic stress [11,12]. Chronic stress experienced by caregivers of children with DD can lead to increased risk for adverse physical health outcomes, including chronic pain, hypertension, obesity, and autoimmune diseases [13-15]. Outside of global pandemic, caregivers of children with DD also report experiencing psychological distress, defined as “a state of emotional suffering typically characterized by symptoms of depression and anxiety” [16, p. 687] at higher rates than caregivers of typically developing children [11,17]. General factors associated with psychological distress among caregivers of children with DD include child behavioral challenges, the child or caregiver’s age, as well as the child’s disability diagnosis and disability severity [18,19]. These challenges, however, have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. For many caregivers of children with DD, schooling from home has meant not only balancing daily caregiving tasks, traditional parenting responsibilities, work obligations, and homeschooling; they also may be faced with implementing specialized instruction, related services, or behavioral interventions for their child [2].

A recent study by Chafouleas & Iovino [10] explored differences in caregiver burden and psychological distress resulting from COVID-19 between caregivers of children with and without DD in the United States following COVID-19-related school closures. Survey results aligned with other preliminary reports [1,2,10], revealing that caregivers of children are experiencing negative outcomes, at differential rates than for other populations, during COVID-19. However, caregivers of children with ASD/ADHD reported significantly higher levels of burden, depression, anxiety, and stress as a result of the pandemic [10].

The impact that family caregiver well-being has on the welfare of children in their care has been well-established [14,19]. Moreover, studies suggest that family caregiver psychological wellbeing may be more impactful than level of exposure regarding the child’s traumatic stress responses following a disaster [20-22]. Many experts consider the COVID-19 pandemic to be just that: a large-scale disaster with the potential to result in traumatic stress responses among children and families [23,24], similar to events such as 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina [22,25]. Caregivers of children with and without DD indicate that they are experiencing immense challenges as a result of COVID-19 [10]. Taken together, the well-being of caregivers of children during and in the aftermath of COVID-19 is a significant public health concern. Yet to date, exploration of caregivers’ experiences has primarily utilized survey data. Initial study results suggest substantial concern regarding the well-being of all caregivers, particularly among those with children with DD [10]. There remains a need to unpack survey findings further by allowing caregivers’ voices to be heard. Qualitative exploration offers the potential to better understand caregivers’ lived experiences during COVID-19 in their own words.

Although recent quantitative survey research has demonstrated a negative impact on the well-being of caregivers of children due to COVID-19 (e.g., Chafouleas & Iovino, [11]), there are no published qualitative studies on caregivers of children with DD during the pandemic to date. There remains a critical need to understand caregivers’ experiences and needs during COVID-19, in their own words, when exploring how to best support these families. As such, the purpose of this study was to expand on the Chafouleas & Iovino [11] survey findings by exploring the impact of COVID-19 on the personal well-being of caregivers of children with and without DD and defining the personal well-being needs of caregivers of children with and without DD as a result of COVID-19.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited in April 2020 as part of an online survey. For additional information on recruitment processes, see Chafouleas and Iovino [11]. Survey participants were asked whether they had interest in being interviewed regarding their experience as a primary caregiver of a child aged 6 to 18 during the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to obtain a diverse sample of caregivers, interested participants were categorized based on their child’s age, disability status, and severity of behavioral challenges. Participants were then randomly selected within each category, with a goal of representation across categories. Participants were contacted to confirm interest in participating in an interview and provided an Interview Information Sheet via encrypted electronic mail. The first 40 selected participants were initially contacted; each time a participant did not respond, withdrew, or did not attend their scheduled interview, another participant in a similar category was randomly selected for interview. Overall, 69 caregivers across groups were contacted for interview. Of those, two withdrew from the study, 36 did not respond to contact, and one participant was removed from inclusion given they did not attend multiple scheduled interviews. A total of 30 caregivers were interviewed in total; 13 were caregivers of children with DD and 17 were caregivers of children without DD. Notably, caregivers of children with DD more often did not respond to the emailed interview request or declined an interview citing a lack of time.

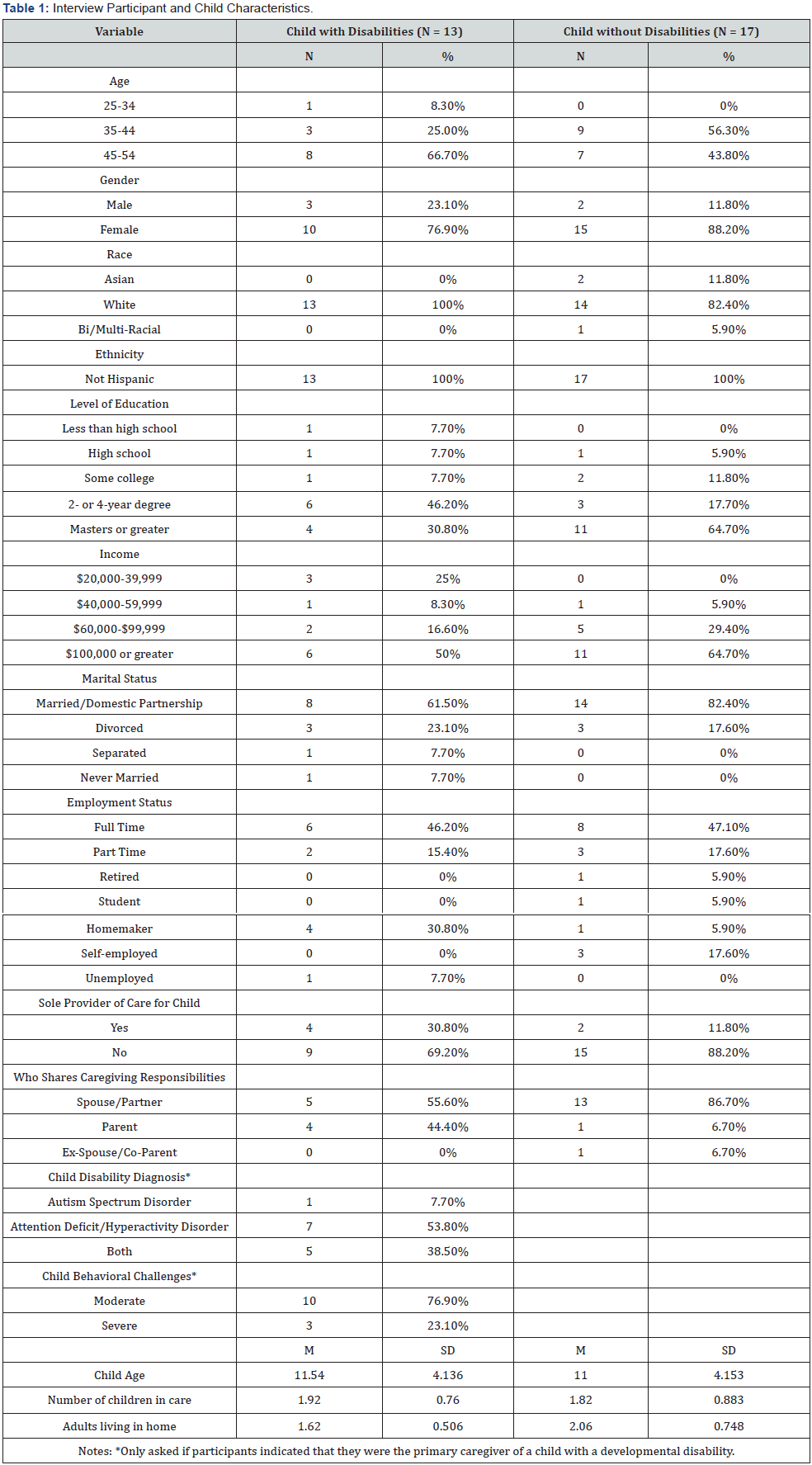

The demographic characteristics of participants in both groups are provided in Table 1. The majority of participants across groups were White (n = 27), and all were non-Hispanic (n = 30) and most identified as female (n = 25) and had at least a 2-year degree (n = 24). The majority of participants earned a yearly income of $100,000 or greater (n = 17). Additionally, the majority were not the sole provider of care for their child (n = 24), and either shared the role with a partner or a parent (n = 23). Roughly half of participants in each group reported being employed full time. When specifically looking at caregivers of a child with DD, most reported that their child was diagnosed with ADHD (n = 7) and exhibited moderate behavioral challenges (n = 10). The average age of their children was 11.54 (SD = 4.136), they cared for and average of 1.92 children (SD = 0.760) and lived with an average of 1.62 adults in the home (SD = 0.506). Among caregivers of children without DD, the average age of their children was 11 (SD = 4.153), with an average of 1.82 children (SD = 0.883) and 2.06 adults living in the home (SD = 0.748).

Procedures

A semi-structured interview protocol was developed to explore the impact that COVID-19 has had on the stress and wellbeing of caregivers of children with and without DD. The interview included eight questions related to the following focus areas: (1) experiences of stress associated with caregiving during COVID-19, (2) assessment of their self-care practices and personal well being, and (3) support needs resulting from COVID-19. At the end of the interview, caregivers were given the opportunity to share additional thoughts.

Upon obtaining confirmation from participants via encrypted electronic mail that they were still interested in participating, the third author scheduled an interview based on the availability of both the participant and the researcher. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes on average and were conducted over a videoconferencing platform. Interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed.

Data analysis

Participant responses were collected into Excel spreadsheets organized by interview questions. The qualitative analysis was completed by following Braun & Clarke’s [26] phased approach. First, the second and fourth authors listened to the audio recordings of the interviews while reviewing the transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data. Next, we began to establish codes for the participant’s responses for each interview question. Then, using an inductive thematic analysis approach that allowed themes to emerge from the data [26], codes from the previous step were combined into similar themes. After, the themes created in the previous step were reevaluated for quality and importance related to the research questions. The themes were then named and defined to identify the specifics within each theme and how they are unique compared to the other themes. Finally, a content analysis method of examining qualitative data was used to identify the prevalence of certain themes [28,29].

While completing the analysis, we also followed Brantlinger et al.’s [27] guidance to ensure quality in our coding procedures, specifically reflective thinking. The second author conducted all participant phone interviews. When completing the interviews, the author needed to consider how her experiences could have shaped conversations with participants. The second and fourth authors completed the initial coding while reflecting on how their experiences could influence their perception of codes and themes. The second and fourth authors collaborated with the first and third authors to increase the credibility of the data by reviewing all final themes.

Results

Several themes across participant responses within each focus area were identified. The results are organized to reflect the order of focus areas presented in the semi-structured interview: (1) experiences of stress resulting from caregiving during COVID-19, (2) general assessment of self-care and personal well-being, (3) support needs during COVID-19, and (4) additional themes contributed by participants.

Caregiving stress

Stress due to childcare responsibilities: Participants were asked to identify stressors associated with caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic. Across both groups, participants reported experiencing stress related to supporting their child’s schooling at home. Among caregivers of children with DD, a common theme was that supporting their child’s education and schooling from home due to COVID-19 was one of their greatest sources of stress (n = 11). Specific stressors included supporting their child in completing school assignments/attending scheduled class meetings (n = 8), replicating special education services/supports at home (n = 6), and balancing schooling with other responsibilities (n = 6). For example, one participant shared: “My kids have IEPs. So, they have accommodations and modifications... that I sort of have to implement. And a lot of that has to do with time management...also, not knowing really what all of their assignments are that they’re missing and finding out after they’re missing them.” Caregivers of children with DD further indicated stress related to managing their child’s challenging behaviors (n = 7) and daily routine (n = 3). In addition, some participants referenced that finding an appropriate workspace for their child was stressful (n = 2) as was managing their child’s physical health needs (n = 2).

Caregivers of children without DD indicated that their greatest sources of stress were their child’s schooling (n = 12) and their ability to care for their child throughout the day (n = 11). Specifically, school related stress reported by caregivers of children without DD was due to routine change and supporting their child’s virtual learning (e.g., requirements, expectations, motivation). For example, one participant shared: “it’s the schoolwork and then trying to keep him busy active and all that... the schoolwork, it’s challenging because sometimes he doesn’t want to do it...I have to get him motivated...and then we’ll butt heads about what he has to get done. And, you know, I was never a teacher...I definitely have less patience at times when he’s doing his work.”

Participants also reported stress related to supporting their child throughout the day, including supervision, managing their daily schedules, and supporting their understanding of the pandemic. Other common sources of stress related to caring for a child included their family’s health and safety (n = 6) and their ability to work (n = 4). For example, a participant stated: “I’ve been in such a reactive mode...one of my kids is...at risk. I have a husband and a kid who’s highly at risk. So, we are hypervigilant… If we see someone walking down the path, we run to the other side...I have two people who have respiratory risks that we have to be hypervigilant.”.

Impact of stress in other areas: All participants reported that the stress related to caring for a child has influenced various aspects of their professional and personal lives. Caregivers of children with DD reported that stress associated with caring for their child during COVID-19 impacted their ability to their balance work obligations with their caregiving responsibilities (n = 7). For example, one caregiver described how working from home while caregiving impacted their stress and well-being: “It’s like the better parent I am, the less work I accomplish. The more work I accomplished, the worse parent I am... they’re not getting enough of me and it’s really hard to balance.” Other aspects of caregivers’ personal and professional lives most commonly influenced by their stress included their relationships (n = 6), leisure activities (e.g., watching TV, art/craft projects, shopping) (n = 5), diet/ exercise (n = 7), and sleep (n = 4). One participant shared with regard to the impact on their relationship: “Relationships...it has put a strain. Luckily, my fiancé has been able to stay at home with [my child] and take on the brunt of the work of watching over him, but it becomes stressful for him, which then trickles down to our connection. So, it’s been exhausting for everybody.” Caregivers of children with DD indicated that their stress impacted their ability to attend to their own physical and mental/emotional needs (n = 4). One participant stated: “I feel like all of the things that I do have been doing in my life for the past, you know, 15 to 20 years to keep myself mentally and physically healthy have been taken away.”

Caregivers of children without DD reported various areas of their professional and personal lives influenced by their caregiving stress. Stress from caring for a child during COVID-19 has influenced their ability to work (e.g., balancing childcare with their workload, change in hours due to childcare, decrease in productivity; n = 7), parenting obligations (e.g., worry about socialization for child, supporting their child throughout the day; n = 7), sleeping patterns (e.g., staying asleep, difficulty falling asleep; n = 6), and ability to exercise (e.g., access to gyms/ organizations to exercise, decreased motivation, decreased time to engage in physical activity; n = 5). For example, one participant shared: “Trying to just coordinate with my spouse...so that I can be on client calls without kids in the background has been...that’s one of the things that we tried to do, and I feel like we’ve actually we do a pretty good job of that. But there have certainly been a few where we couldn’t make it work. And I just had to have the kids around and...you get a lot of lip service. A lot of folks ‘Oh, I understand your situation. I can’t believe you’re doing this. I’m so impressed. Oh, you’re like my hero.’ But then you actually get on the call. And people seem less than enthused that your kids are making a racket in the background.”

Additionally, participants reported stress around financial concerns (e.g., salary cuts, loss of employment; n = 5), leisure activities (e.g., inability to access activities, decreased time to engage in activities, challenges finding activities for their family; n = 4), relationships (e.g., inability to engage in social relationships, strains on relationships with family members, difficulty making virtual social commitments or taking time for themselves; n = 4), and mental health (e.g., difficulty focusing on task, worrying at night instead of sleeping; n = 4). One participant noted: “And the other concern I would say is if something happened to both me and my husband, those are the things that, I’m not gonna say keep me up at night but are in the back of my mind. And there are nights where I’ll think about it more and I can’t get sleep.”

Personal well-being

Self-care behaviors prior to COVID-19: When participants were asked about their self-care routines prior to COVID-19, common themes across both groups included engaging in exercise and spending time with family and friends. Prior to COVID-19, caregivers of children with DD reported engaging in self-care behaviors such as exercise (n = 9), leisure activities (e.g., going to a salon/spa, reading for pleasure, going to the movies) (n = 7), eating a balanced diet (n = 5), spending time with friends and family (n = 6), attending personal appointments with professionals (n = 3), practicing relaxation strategies such as meditation (n = 3), and volunteering/advocacy projects (n = 3). For example, one participant stated: “Well, she had therapies, so she had someone who came into the house a couple times a week, and I could at least, even if I just did yard work or...step away and read or play a game, or just have a little bit of time to myself in the afternoons. I think that’s one thing...while she’s at school, that does sort of just give me time to...do whatever I need to do and then not have to think about it.”

Individuals also referenced self-care activities such as participating in online or in-person support groups (n = 1), going to a place of worship (n = 1) and keeping a healthy sleep schedule (n = 1). Two participants described their self-care practices in terms of their daily living activities, such as “taking a bath or shower” and “getting dressed.” Three caregivers of children with DD remarked that engaging in self-care behaviors was challenging for them prior to COVID-19, with one noting, “There was no extra time to have done things back then either. I had problems with self-care before this happened.”

Caregivers of typically developing children indicated that prior to COVID-19, their self-care behaviors included exercise (n = 16), time with family and friends (n = 10), leisure activities (e.g., shopping, eating at restaurants, going to salons, n =10), and time for self (n = 4). For example, one shared: “You know, just going to the movies, even something simple like that, or actually. I’m somewhat dawned on me yesterday that I was somewhat devastated that Marshall’s isn’t open, and I can’t go to Marshall’s.” Regarding participant engagement in physical activity prior to COVID-19, caregivers reported having time that they can prioritize to exercise each week, utilized their lunch breaks to walk, and had access to gyms/studios to complete their exercise routine. One participant noted: “I was maybe working out at least, like, two or three times a week and just for like, longer periods” I know it sounds silly, but just to be able to take like an hour to myself, you know, now I take 20 minutes at most. Bike riding. I was a big bike rider, I would be biking a ton right now if it weren’t for this, probably not that biking is actually a bad thing to do, I just don’t have time.

Ability to engage in self-care behaviors during COVID-19: As a result of COVID-19, most participants across groups identified a decrease in their ability to engage in self-care routines, including exercise and social relationships. Caregivers of children with DD largely indicated that their self-care behaviors were impacted by COVID-19, including their ability to see friends or family (n = 7) and their ability to access self-care resources in the community such as places to exercise (n = 5), and healthy food sources (n = 3). Some participants also referenced ability to access mental/emotional resources (e.g., therapy) (n = 2) and their place of worship (n = 1). Caregivers also reported a decreased ability to engage in leisure activities (n = 3). Two participants also indicated decreased time for themselves. For example, one shared: “everything’s harder. So, struggling to get out of the house and exercise, yes...I went running one day, and I was like, ‘This is great. I gotta do this, like, several times a week.’ And then the next thing I know...even the morning I’m like, ‘It’s gonna be my plan, I’m gonna figure it out somehow.’ And then it’s like eight o’clock, it’s time to put the kids to bed.”

However, some caregivers of children with DD remarked that they struggled with self-care both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, one participant stated: “I think I’m just doing the status quo of no self-care that I was doing before COVID-19.”

As a result of COVID-19, caregivers of children without DD reported variable changes to their self-care routine. Many participant responses indicated a negative impact on their social relationships (n = 7), including their ability to be alone with their significant other, inability to see individuals in person, and adapting to guidelines/media platforms to engage in social interactions. Additionally, engagement in leisure activities (e.g., dining at restaurants, pampering themself at a salon, shopping; n = 6) decreased due to caregivers’ inability to access businesses and parks. One participant noted: “I think just being able to go out on a date night with my husband like, I think our ability to kind of connect and you know, go out and eat at a restaurant or just kind of have that time to ourselves outside of the house has been tough.” Caregivers also indicated a decrease in their ability to exercise (n = 6) or engage in mindfulness activities (n = 3). However, some caregivers of children without DD indicated that there was either no significant impact or an increase in ability to engage in self-care behaviors (n = 6). Participants who indicated no change in their ability to engage in self-care behaviors reported adapting their self-care routine to support their current lifestyle (e.g., virtual interactions, online workout classes). For example, one participant indicated: “I don’t think it’s been a struggle for us. It’s just been different. So just finding like online, you know, like a Zoom, Google Hangout with friends...we do live in a cul de sac, so when it’s nice outside...we will do a social distance and have a drink if it’s warm outside maybe once a week with a couple of our neighbors...we’ve just found other ways to adhere to the stayat- home order and the social distancing, but still find ways to be social.”

Another participant shared: “Because I’m home more and not traveling for work, I do get the opportunity to exercise more. So, I’ve just adapted my self-care to things that I can do now that I have time for them and making sure that I make participate in those activities.”

Self-care behaviors desired and resources needed: Participants were asked about their desired self-care behaviors and the resources needed to engage in them. A common theme across both groups of caregivers was a desire to increase exercise and time spent with family and friends, but that businesses (e.g.,gyms, parks, salons) would need to reopen for this to occur. Caregivers of children with DD identified regular physical activity (n = 6), social interaction with friends/family or alone time with a significant other (n = 5), and leisure activities (e.g., shopping, going to a salon, golfing; n = 3), as some of the self-care behaviors they would most like to engage in during COVID-19. In order to engage in regular physical activity, caregivers noted that gyms or parks would need to open to the public. Some caregivers suggested alternative resources to indoor gyms (n = 3), such as remote gym instructors, outdoor gym classes, and virtual exercise accountability partners. Others stated that widespread access to personal protective equipment (PPE) or a vaccine would be needed to attend social gatherings or exist in public spaces (n = 2). Caregivers of children with DD further expressed the need for respite to be able to engage in desired self-care behaviors (n = 7). For example, one shared: “As a caregiver…Just even 5 or 10 minutes of just being able to breathe without ‘Mom, Mom, Mom, Mom’ or ‘I want, I want’, um, is really beneficial. So yeah, having just having that having that extra pair of hands around is something that I really miss.” Additionally, caregivers of children with DD indicated the need for either virtual or in-person access to doctors or support groups to address ongoing physical and/or mental health needs (n = 3).

Caregivers of children without DD reported a variety of selfcare behaviors that they would like to engage in. Some participants mentioned that they would like to increase their physical activity, but that businesses would need to reopen to accomplish this (n = 6). Also, some participants desired social relationships including alone time with their significant other, socializing with friends, and gathering for celebrations (n = 5). Caregivers also reported needing childcare supports to assist with tasks throughout the day and help to balance working from home with their child’s schooling (n = 5). One participant shared: “I think we need childcare. Like I think I need somebody to come pick my kid up for a little bit honestly. And whether that’s for me to spend time by myself or me to spend time with my husband or me to call a friend and just have like a long phone conversation...” Participants identified needing virtual supports to increase their ability to engage in self-care (n = 5). Some caregivers reported no need for additional self-care behaviors or resources to complete them (n = 3). One participant shared: “I do have a counselor that I see every couple weeks, and I’m just doing it online. It’s not... ideal, I prefer to be in person with her. Um it’s not the worst thing in the world either. No, ironically, I think in many ways this forced me to do more self-care than I normally would”

Support needs

Types of support: When asked about their support needs, participants in both groups reported needing support in the areas of additional assistance with their child’s digital learning and emotional/informational resources. Caregivers of children with DD expressed the need for greater assistance from the school in facilitating their child’s learning from home (n = 9). Of these participants, four specified needing support around implementing special education (e.g., modifications and accommodations) and related service (e.g., speech pathology, occupational therapy, school psychology) supports. For example, one caregiver reported: “I’d probably like a little more information…so I can know more about exactly how I can support and have her maintain her skills… That would be helpful. I’d probably feel better about what I’m doing with her if I had a little more guidance.”

Caregivers of children with DD also reported needing emotional and/or informational support such as counseling or support groups (n = 5), as well as greater social/emotional supports for the child(ren) in their care (n = 6). One caregiver noted: “emotional support for us...for caregivers alone, there really is not a lot of emotional support out there. And then now it just kind of even widens that gap even more of having really no resources for emotional support, and where we live, there’s really not a lot...Especially during these times because it’s so uncertain... it’s a lot, it’s draining, and to not really have free time, kind of being the caregiver 24-7, and being the educator 24-7, and trying to just find a balance of homeschool, fun.”

Many caregivers emphasized their need for respite (n = 6), with one caregiver reporting: “I think where I’m coming up short... I really think that if there were some sort of respite available...any kind of respite that would get me out of the house for a little while or something, would be very, very valuable.”

Regarding areas of support, caregivers of children without DD indicated they need various sources of support during this time. Many participants responded needing either informational support from reliable sources (n = 5) or emotional support from family members and friends (n = 5). Some reported needing additional assistance supporting their child’s schooling at home (n = 4). One participant noted: “I’m not seeing a lot of information regarding...how do we deal with the reentry of going back to school, how do we deal with the reentry of going back to a dance studio or gym...where’s that transition piece? It’s how to deal with things now, and what we’ll deal with in that when it’s open. But where’s the reentry? And I think that would be beneficial because I’m not even sure how to explain that to my two children.”

Lastly, some participants in this group also indicated that they had enough resources and support in place (n = 6). For example, one participant shared: “I think that me personally, I’m not sure if I need more support. I think of my kids and them needing more social support. I think I’m doing okay.”

Preparation supports: When asked to identify what would have helped them prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic, most caregivers across groups reported needing support for their child’s digital learning to help prepare. Caregivers of children with DD overwhelmingly expressed that resources to support their child’s learning from home would have been beneficial (n = 11). For instance, caregivers indicated that their child and they could have been better prepared for distance learning in terms of the online learning tools used (n = 6). One caregiver stated: “The other thing that has impacted me with regard to the kids in school...I think just having more knowledge and familiarity with their online systems... I think if that was something that was being incorporated into the learning process more before the pandemic, then it would have been easier to make that transition.” Another caregiver noted how preparation for distance learning could be beneficial beyond the pandemic: “I mean, it certainly would have been helpful if the schools had a plan in place for [distance learning]. And the parents had been provided some training or some knowledge of it because they ended up kind of developing it on the fly...any number of things could shut down the schools these days...terrorist threats or mold...one of our middle schools was shut down this year because of mold. So, the kids are dealing with the fact that they’re all crammed into one middle school. If they’d had a plan in place where they could have done remote learning, distance learning, then maybe they could have handled that transition differently.”

Caregivers of children with DD also reported wishing they were better prepared to implement special education and related service supports from home (n = 4). For example, one participant stated: “I’m in a position where I have these two special needs kids at home that generally have had a team of professionals working with them. And I have been left, in a sense, to try and meet all of those professionals’ needs, including occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech therapists, school psychologists...I think that there’s a lot of parents who are really struggling to try and meet those needs because these are very specialized areas. I think now that’s where the current issue is, whereas before I did have support.”

Other desired preparation resources included greater knowledge of their child’s expected school-day routine (n = 3) and improved school technology for their child (n = 2). Caregivers further indicated that greater access to mental/emotional resources would have helped prepare them for the pandemic (n = 3). For example, one participant stated: “I think just a little more guideline as to emotional resources, mental health, and even activities that can be done across all kinds of families, that would help. Maybe getting together and having those telehealth appointments or just being set up with maybe your primary care for...a half hour appointment just to check in mentally. Because like I said, sometimes your anxiety heightens and you’re already at the top before you even realize that you’re at the top.”

Caregivers of children with DD identified other preparation support needs such as PPE (n = 4) and basic supplies such as prepared foods and toiletries (n = 3). Others indicated more individualized needs, such as financial support (n = 2), activities to complete at home with their children (n = 1), behavior management strategies (n = 1), a better space in the home for their child to complete academics (n = 1), exercise equipment (n = 1), and clear guidelines and information about the COVID-19 virus (n = 1).

Caregivers of children without DD reported needing preparation resources and supports in relation to digital learning, access to essential items, and supports for students. For schooling supports, caregivers of students without DD reported needing additional assistance for digital learning and increased understanding about expectations for digital learning from the school (n = 7). As one participant shared: “I think if I would have had an opportunity, and I’m all parents would have had an opportunity to work with the school or the classroom teachers to say, ‘give us an idea of what we should be expecting or what should we what should a day look like for at home learning.’” Another support need indicated by participants was access to essential items, including starting a stockpile earlier and wishing that grocery stores began limiting the number of items earlier in the quarantine (n = 6). For example, one participant stated: “It’s like just even the basic toolkits for keeping a healthy house you know, who knew that we had to have a stockpile of Lysol and Clorox wipes and bleach and, you know, rubbing alcohol like, I don’t know, like who knew that?” Caregivers also reported wanting their children to have additional supports including technology skills and supports for completing assignments (n = 4). Additionally, some participants reported feeling prepared prior to the beginning of COVID-19 due to having preparation supplies at home before quarantine began, relying on international news, and being caregivers of older children who are self-sufficient (n = 4).

Access to preparation supports.Caregivers of children with DD also noted that related service providers/school support staff could have provided them with more guidance around navigating their child’s special education supports and services from home (n = 3), for instance by hosting regular check-ins. One participant stated: “I would have liked to have heard from his guidance counselor and his IEP coordinator to help us along with things that I know that they worked on in school and could have just brought here into the home...which then trickles down to me doing a lot of research. And one more When asked from who or where they might have accessed their previously identified preparation supports, caregivers of children with and without DD both identified their child’s school as the main source responsible for providing these supports. In particular, caregivers of children with DD stated that they would predominantly look to their child’s school for preparation supports (n = 8). Participants largely indicated that schools could have better prepared them through improved communication across school, home, and community systems. For example, participants reported that schools could have prepared them by providing training on the online learning systems used by the school (n = 4) and distributing valuable, relevant resources to support their child with DD (n = 3). As one participant explained: “Maybe something that was a little bit more... ‘Alright, these resources are great resources.’ Instead of as a parent going through all the resources...just being a little bit more organized and like...what is actually going to be helpful for my child...I mean we’re just bombarded with so much stuff... So, just being a little bit more aware of online tools and maybe utilizing them a little bit more. With more quality than quantity.”

Caregivers of children with DD also noted that related service providers/school support staff could have provided them with more guidance around navigating their child’s special education supports and services from home (n = 3), for instance by hosting regular check-ins. One participant stated: “I would have liked to have heard from his guidance counselor and his IEP coordinator to help us along with things that I know that they worked on in school and could have just brought here into the home...which thing, you know, in my bucket, that’s always already overflowing.”

Caregivers of children with DD suggested that schools could have provided them with mental/emotional resources or supports (n = 3). One participant remarked: “I think the schools could be providing a little bit more emotional support to parents who are asked to play this outsized role in their [child’s] education process. And then add special education on top of it...I feel what I’m being asked to do is really difficult and I don’t have the support from the school to do it. And actually, that’s causing me all my stress 24/7.”

Some participants reported wishing that their child’s school had better connected them with other caregivers in their school community (n = 3). One participant suggested: “I think a perfect resource would be getting together with [previously] homeschooling parents and having some type of committee, maybe for every school district. And then that way if school were to ever have to happen at home, we would have those professionals that actually have been doing it for a while to help us transition from public school to homeschooling.”

Caregivers of children with DD also noted that local, state, and/or federal government agencies could have provided them with more preparation supports (n = 4). One participant remarked: “To [be able to] work less, I mean, I feel like that’s kind of like a government responsibility...I feel like the top should be doing more...I feel like I’m doing the best I can, but I feel like there needs to be more support from like the government.”

Most caregivers of children without DD identified that the school system should provide the preparation supports for distance learning expectations and supports for students (n = 10). Specifically, participants would have ideally liked to receive plans for distance learning, to have consistency with assignments across grade levels, to incorporate social interaction into their child’s schedule, and to provide educational supports for their child (e.g., time management, technology assistance). Other themes identified by caregivers of children without DD included informational support about reopening plans and resources for parents (n = 4) and emotional support from community groups/ agencies or online groups using platforms like Facebook (n = 3). One participant shared: “I think the school should have provided more supports for families. I think they should have asked what we needed. I think they should have been responsive based on feedback that was specifically solicited, instead of acting so quickly, just to do what they thought was best, which I understand how schools operate. But nobody ever asked us what we wanted. So, I think that would have been helpful.”

Some caregivers of children without DD reported receiving enough assistance from their school districts and communities (n = 3). For example, one participant noted: “I can’t really think of anything that we’re missing or that could be done better. I mean, when you look back at it, you can always say this or that could have been done better. But at the end of the day, I’m not sure how much of a difference that makes.”

Additional themes

At the conclusion of the interviews, participants were asked if there was a topic or concern that they would like to discuss that was not covered. A common theme reported by both caregivers of children with DD (n = 3) and caregivers of children without DD (n = 10) was concern about the negative impact that COVID-19 might have on the well-being of children. A participant who cares for a child without DD stated: “When he does go back [to school], it’s going to be different. And I think that all of these things will have some kind of long-term effect on him. And whatever I can do now, to prevent there being too much scarring or whatever. I’d like to know what that is that we can do for the kids.” Several caregivers of children with DD relayed concerns about regression of their child’s well-being, as well as their daily living skills. For example, one participant shared: “It’s actually a matter of self-care for the kids, adequate self-care for my children. I find that I’m routinely having to encourage and have my son constantly reminded to take care of his hygiene, eat better. I’m seeing a lot of regression in terms of eating for both of the children, whereas they might have had more balanced meals when they were structured in school. My daughter is struggling with her eating and just general selfcare. And I do think that being confined much more than not has created some mental health issues for the kids...I can’t see how this could be good for them. It’s necessary, but it’s not good for them.”

Overall, participants indicated concerns about the implications of COVID-19 on child development.

Caregivers of children with DD further emphasized concerns about caregiver burden and lacking caregiver supports. One participant shared: “having a child with a disability is a whole different ballgame...when she was first born, from zero to three, I was a stay-at-home mom. And this whole COVID-19 just like brings up like all that trauma of how hard of a transition that was. And this just throws everything back onto the fire except for the fact that now I’m also trying to work, I’m not just trying to be a parent to a kid with a disability.”

Another caregiver stated: “caregivers at home aren’t given any support really. So, I feel maybe...in the future, caregivers in general would get a little bit more resources, a little more identifying information as far as resources, where to go if you need help...I think just kind of stepping up our level of empathy and encouragement for stay-at-home caregivers or even caregivers that have to work from home.”

Discussion

Results of this study contribute to our knowledge about the impact of COVID-19 on family caregivers, particularly with regard to stress associated with caring for a child with and without DD, self-care, and support and resource needs. Findings are consistent with the results of other studies on the experiences of stress and burnout among caregivers as a result of COVID-19 [3,7,9] In addition, similar to Chafouleas and Iovino [11], the present study highlights the unique challenges associated with caring for a child with DD during a global pandemic. Specifically, prior to the pandemic, caregivers of children with DD were already struggling with regard to their personal well-being, which has now been magnified as a result of COVID-19.

The impact of stress due to caring for a child influenced both professional and personal areas of most participants including balancing work obligations, ability to exercise, and inability to sleep. Most participants reported experiencing stress due to supporting their child’s education from home. Both groups of caregivers indicated having greater levels of stress associated with supporting the expectations and requirements of digital learning. In addition, parents of children with DD reported that trying to replicate their child’s special education supports and when managing their child’s challenging behaviors led to increased levels of stress.

Regarding personal well-being, most participants reported engaging in some sort of self-care activity. Common self-care activities reported by both groups included exercise and spending time with family and friends. As a result of COVID-19, participants in both groups reported a decrease in their ability to engage in their self-care routines, specifically their ability to spend time with family and friends and their ability to exercise. Both groups of caregivers reported wanting to increase exercise and their social relationships but reported needing businesses to reopen to engage in these activities (e.g., gyms, parks, salons). However, some caregivers of children without DD reported that their selfcare routine improved as a result of the pandemic. For caregivers of children with DD, some reported having limited time for selfcare before the beginning of COVID-19, which continued or worsened during the pandemic.

With regard to support needs resulting from COVID-19, common themes across groups were the need for assistance with their child’s online schooling and informational/emotional supports. Additionally, most caregivers reported wanting supports for online schooling, which would have ideally been provided by their child’s school. Caregivers of children with DD also indicated the need for related services personnel to provide information and guidance for implementing their child’s educational plan at home.

Some participants raised additional concerns focused on their children that were not addressed in the semi-structured interview protocol which targeted the caregiver. Across groups, caregivers expressed concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on the wellbeing of their child(ren) and overall child development. Among caregivers of children with DD, this also included concerns about regression of their child’s self-care skills. In addition, caregivers of children with DD discussed a lack of caregiver supports and increased caregiver burden as challenges that have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Limitations and future directions

The present study is not without limitations. For one, limitations are noted with regard to the characteristics of the overall sample given that all participants in both groups were largely White/non-Hispanic and the majority were at least collegeeducated with an annual household income of at least $100,000. In addition, participants tended to be older, female, and working. As such, these findings are not generalizable to caregivers with diverse personal demographics in addition to characteristics associated with financial stability. Additionally, the second author is a graduate student, which could have influenced participants’ willingness to share personal experiences during the interviews or potentially shaped participant responses based upon her professional and personal background. Despite the limitations, current findings are important in helping to unpack results from quantitative work which has tended to support substantial negative outcomes for family caregivers.

Given the ongoing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, continued research is needed on both the short- and long-term impact on caregivers of children, particularly those with DD. Specifically, continuing to engage caregivers in interviews or focus groups throughout the evolution of the pandemic may help to guide directions in both research and practice. In terms of research, caregiver needs identified through interviews or focus groups can help shape survey or intervention research. In addition, future research on caregivers should specifically seek to recruit diverse caregivers to identify challenges experienced by these populations. With regard to practice, listening to caregiver voices and perspectives on their own and their child(ren)’s needs can help practitioners to engage in effective decision making related to assessment and intervention for children and caregivers.

Implications and applications

Overall, although all caregivers indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on themselves and their families, caregivers of children with DD reported more challenges across areas. In particular, caregivers of children with DD indicated a need for greater supports, both for themselves and for their child(ren). Given that many states have started or are starting school remotely [30], it is critical to consider the needs of children with DD and their caregivers to support the best outcomes possible for this population. Although caregivers of children with DD indicated some common challenges, there was variability in participant responses based on individual or family needs. This indicates that schools should elicit information and feedback from caregivers themselves in order to most effectively engage in decision making and provision of supports for caregivers of children with and without DD.

Acknowledgment:

This study is funded by a seed grant from the University of Connecticut’s Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP).

References

- Cluver L, Lachman JM, Sherr L, Wessels I, Krug E, et al. (2020) Parenting in a time of COVID-19. The Lancet 395(10231): E64.

- Coyne LW, Gould ER, Grimaldi M, Wilson KG, Baffuto G (2020) First things first: Parent psychological flexibility and self-compassion during COVID-19. Behavior Analysis in Practice, pp. 1-7.

- Russell BS, Hutchison M, Tambling R, Tomkunas AJ, Horton AL (2020) Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: Caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent-child relationship. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 51: 671-682.

- Park CL, Russell BS, Fendrich M, Finkelstein-Fox L, Hutchison M, et al. (2020) Americans’ COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. Journal of General Internal Medicine 35: 2296-2303.

- Pew Research Center (2020) Most Americans say coronavirus outbreak has impacted their lives.

- Griffith AK (2020) Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence 1-7.

- Lee SJ, Ward KP (2020) Research brief: Stress and parenting during the coronavirus pandemic. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Parenting in Context Research Lab.

- Ananat E, Gassman-Pines A (2020) Snapshot of the COVID crisis impact on working families. EconoFact.

- Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, Koppels T (2020) Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect 110(2): 104699.

- Chafouleas SM, Iovino EA (2021) Comparing the initial impact of COVID-19 on burden and psychological distress among family caregivers of children with and without developmental disabilities. School Psychology. Advance online publication.

- Chafouleas SM, Iovino EA, Koriakin TA (2020) Caregivers of children with developmental disabilities: Exploring perceptions of health-promoting self-care. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 32(6): 893-913.

- Iovino EA, Chafouleas SM, Sanetti LMH, Gelbar N (in press) Pilot evaluation of a Facebook group self-care intervention for primary caregivers of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies.

- Auerbach E, Perry H, Chafouleas SM (2019) Stress: Family caregivers of children with disabilities. UConn Collaboratory on School and Child Health.

- Murphy NA, Christian B, Caplin DA, Young PC (2006) The health of caregivers for children with disabilities: Caregiver perspectives. Child: Care, Health and Development 33(2): 180-187.

- Schulz R, Sherwood P (2008) Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. American Journal of Nursing, 108(9): 23-27.

- Arvidsdotter T, Marklund B, Kylén S, Taft C, Ekman I (2016) Understanding persons with psychological distress in primary health care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 30(4): 687-694.

- Scherer N, Verhey I, Kuper H (2019) Depression and anxiety in parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 14(7): e0219888.

- Catalano D, Holloway L, Mpofu E (2018) Mental health interventions for parent carers of children with autistic spectrum disorder: Practice guidelines from a critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15(2): 341.

- Lindo EJ, Kliemann KR, Combes BH, Frank J (2016) Managing stress levels of parents of children with developmental disabilities: A meta‐analytic review of interventions. Family Relations 65(1): 207-224.

- Garrison CZ, Bryant ES, Addy CL, Spurrier PG, Freedy JR (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents after Hurricane Andrew. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(9): 1193-1201.

- Joshi PT, Lewin SM (2004) Disaster, terrorism: Addressing the effects of traumatic events on children and their families is critical to long-term recovery and resilience. Psychiatric Annals 34(9): 710-716.

- Rowe CL, Liddle HA (2008) When the levee breaks: Treating adolescents and families in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 34(2): 132-148.

- Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N (2020) The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine 180(6): 817-818.

- Horesh D, Brown AD (2020) Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 12(4): 331-335.

- Kerns CE, Elkins RM, Carpenter AL, Chou T, Green JG, et al. (2014) Caregiver distress, shared traumatic exposure, and child adjustment among area youth following the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Journal of Affective Disorders 167: 50-55.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77.

- Brantlinger E, Jimene, R, Klingner J, Pugach M, Richardson V (2005) Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional children 71(2): 195-207.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15(9): 1277-1288.

- Saldaña J (2011) Fundamentals of qualitative research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Education Week (2020) School districts' reopening plans: A snapshot.