The Effects of Antecedent Interventions on Oral Reading Fluency: A Case Report

Harry M Voulgarakis* and Kerry Ann Conde

Department of Child Study, St. Joseph’s College, USA

Submission: May 26, 2021; Published: July 12, 2021

*Corresponding author: Harry M Voulgarakis, Department of Child Study, St. Joseph’s College, USA

How to cite this article: Harry M V, Kerry A C. The Effects of Antecedent Interventions on Oral Reading Fluency: A Case Report. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil, 2021; 8(4): 555744. DOI:10.19080/GJIDD.2021.08.555744

Abstract

Individuals with autism spectrum disorders present with many behavioral, cognitive, and psychological deficits that impact their learning. Literacy and reading fluency are often areas of concerns. Miscues or oral reading errors are frequently used as a metric for measuring fluency within a reading passage. This study employs an alternating treatments design to compare two antecedent interventions to promote oral reading fluency: silent text preview and oral/listening preview. Data from these interventions demonstrate increased oral reading fluency resulting from both interventions, with listening previewing showing greater treatment effect by reduction of miscues. Strengths, limitations, and recommendations for future research are discussed [1].

Keywords: Oral reading; Antecedent intervention; Miscue analysis

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder marked by deficits in social communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive behavior. ASD affects many areas of psychological and behavioral functioning including cognition, social abilities, and adaptive and daily living skills. Both children and adults with ASD can also present with complex educational profiles, despite in-tact cognitive abilities. Notably, reading and literacy are often areas of weakness [2].

Oral reading is used to measure an individual’s overall reading performance to examine various aspects of reading abilities such as rate, accuracy, and fluency that can otherwise not be observed from silent reading. These abilities have also been shown to be strongly correlated with comprehension; that is, students with stronger oral reading abilities (i.e., rate, fluency, and accuracy) consistent with age and grade expectations tend to do better with respect to reading comprehension [2,3]. Previous research has demonstrated that repeated oral reading and listening to a model are effective antecedent interventions to improve fluency for “troubled” youth and those with and without disabilities [4,5].

Individuals with ASD may demonstrate above average word recognition (i.e., hyperlexia), but below average reading comprehension, both of which develop independently of each other [2]. 65% of children with ASD who have measurable reading skills have difficulties with reading comprehension [6] underscoring the need for individualized reading interventions that focus on decoding and fluency [2,5]. Therefore, in order to better understand behavioral interventions that can support the development of oral reading abilities, the present study seeks to determine effective antecedent procedures to reduce miscues during oral reading in a student with ASD. Reading aloud and listening to a model will be compared to determine which intervention is more effective for an individual with High Functioning Autism and a learning disability.

Methods

Participant and setting

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at St. Joseph’s College. This single subject study included one participant, “Peter”, under the age of 18, who had been identified as having a learning disability, specifically with respect to reading. The student has also been diagnosed with ASD, with intact cognitive abilities falling in the Low Average range based on previous IQ testing. The student has been tested and found not to have dyslexia, but a broad disorder in reading ability. Intervention was conducted one on one in the school setting.

Design and procedure

A single-subject, alternating treatments design was employed for this study during daily reading sessions at this school. Following baseline, two interventions were implemented: A) Silent Preview of Text; and B) Listening Preview. For consistency, interventions were delivered in this order during each session. Data were collected on the number of errors (miscues) made each time the student was asked to read aloud. Substitutions, omissions, insertions, or hesitations greater than five seconds were each be recorded. For word which the student could not effectively decode on his own and no response was elicited (i.e., hesitation for 5+ second with no attempt at pronunciation), the miscue was recorded he was provided the correct pronunciation. Similarly, if he attempted to and incorrectly pronounced a word, the miscue was recorded, and the correct pronunciation was provided. The following describes the baseline conditions and specific interventions implemented for this study:

Baseline: The student was presented with a reading passage that was equivalent to his instructional level based on previous testing using the Qualitative Reading Inventory, Sixth Edition (QRI-6).

Intervention 1: Silent Preview of Text. The student was presented with a passage at the instructional level based on QRI-6 results and was asked to silently read the passage to himself. The student was then asked to read the passage aloud to the researcher where miscues were recorded as indicated above.

Intervention 2: Listening Preview. In the Intervention 2 phase, the student was provided a copy of the passage and asked to follow along while the examiner read the passage aloud. The student was then asked to read the passage aloud to the examiner where accuracy (miscues) were recorded.

Inter-observer agreement

A second trained observer was present for 50% of sessions, independently collecting data. Data was only considered to be valid and reliable when there was a minimum of 90% agreement between observers. A mean of 98% agreement was observed, and all sessions met the 90% minimum criterion.

Results

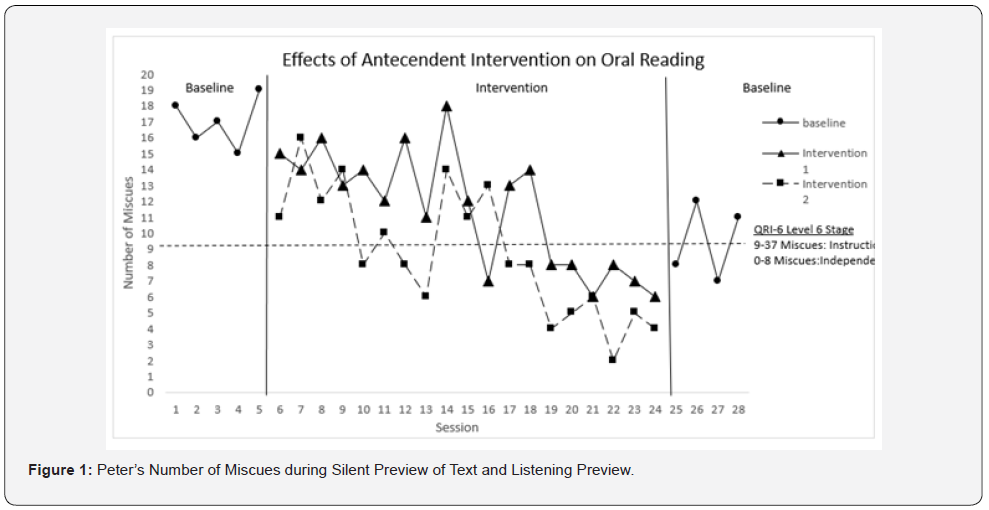

At baseline, the student’s number of miscues per passaged ranged from 15 to 19, which falls in the Instructional range in level 6 on the QRI-6. The Instructional range at this level allows for 9-19 miscues, while 8 or fewer is considered to be the Independent range. It is important to note that the dashed horizontal line in Graph 1 depicts the distinction between these levels and should not be confused with a mean or median level line. Interventions were compared to baseline levels via visual analysis of the data.

Both Silent Preview and Listening Preview were implemented for 18 sessions across different Level 6 passages of similar length. The split-middle line of progress method [7,8] was implemented to analyze the data and compare means. For Silent Preview, the first half of intervention (9 sessions) resulted in a mean of 14.3 miscues per session, while Oral Preview resulted in a mean of 11. Both Intervention 1 and 2 resulted in reduction of miscues, however both means continue to fall in the Instructional range on the QRI-6. In the second half of the data series (10 sessions), Silent preview produced a mean of 8.9 miscues, while the Oral Preview resulted in a mean of 6.6 miscues. If rounded up to 9, mean number of miscues for Silent preview resulted in performance still in the Instructional range on the QRI-6. Oral Preview in the second half of the intervention phase resulted in performance falling in the Independent range on the QRI-6.

In the final phase, both interventions were removed, and baseline conditions were restored. In this condition, five data points were collected. Two of the five data points fell in the Independent range. Still, despite three of the five presenting in the Instructional range they still demonstrate significant reduction in miscues generalized to baseline conditions sans any intervention present.

Discussion

The results of this study extend the available research on the utility of simple, easy-to-implement antecedent interventions to support the development of oral reading skills. It is important to note that each passage chosen was at the student’s instructional level, and it is likely that many words were repeated in passages across sessions, thus increasing the students exposure to seeing and hearing each word. This, in turn, likely contributed to his success over time and, thereby, reducing miscues.

There are various strengths to this intervention, in particular, the ease of implementation. The brief passages also allowed repeated exposure and rapid implementation of trials for each session. Despite its many strengths, this study should be considered within the context of several limitations. Generality of this intervention to students with different abilities and service provision may be challenging due to the relative intensive nature of the intervention (i.e., one-on-one with reading teacher every day) that other students may not have access to. This intervention, could however, be conducted in a group setting, though recording of miscues would prove challenging in such a setting. Further investigations into the implementation and efficacy of small group intervention utilizing the same methods are warranted.

Due to the high frequency of reading probes per session with the reading teacher, the student appeared to become bored with the task and made comments such as, “Oh this again.” Adding a consequence intervention (i.e., a reinforcement element) may be helpful in mediating these concerns as well as increase the speed and efficacy of intervention. Finally, in further research, and systematic analysis of generalization and maintenance probes within an experimental design would be helpful in determining long term effects of the intervention as well as check for comprehension.

Implication for Practice

a) Antecedent interventions are an effective choice for supporting the development of oral reading fluency.

b) Text preview and oral review are effective means of intervention for oral reading deficits.

c) Antecedent interventions are brief and easy to implement in many settings.

d) Reading skills can be promoted through repeated and modeled exposure to grade levels words (Figure 1).

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Saint Joseph’s College, New York.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn). Washington, DC: CBS Publishers and Distributors.

- Randi J, Newman T, Grigorenko EL (2010) Teaching children with autism to read for meaning: Challenges and possibilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 40(7): 890-902.

- Hasbrouck J, Tindal GA (2006) Oral Reading Fluency Norms: A Valuable Assessment Tool for Reading Teachers. The Reading Teacher 59(7): 636-644.

- Ardoin SP, Williams JC, Klubnik C, McCall M (2009) Three versus six rereadings of practice passages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 42(2): 375-380.

- Swain KD, Leader-Janssen EM, Conley P (2013) Effects of repeated reading and listening passage preview on oral reading fluency. Reading Improvement 50: 12-18.

- Nation K, Clarke P, Wright B, Williams C (2006) Patterns of reading ability in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 36(7): 911-919.

- White OR (1972) The split-middle: A quickie method of trend analysis. Eugene, OR: Regional Center for Handicapped Children.

- Wolery M, Harris SR (1982) Interpreting results of single-subject research designs. Physical Therapy 62(4): 445-452.