The Mediating Role of Perceived Scholastic Competence in the Relationship between Motor Coordination and Academic Performanceioural Disturbance in People with Intellectual Disability

Nickolas Ledwez, Samantha Perrotta, Alex Lemay, Mitchell Ianiero and Brent E Faught*

1 Department of Health Sciences, Brock University, Canada

2 Professor of Epidemiology, Department of Health Sciences and Graduate Program Director for the Master of Public Health degree program, Brock University, Canada

Submission: March 22, 2021; Published: April 19, 2021

*Corresponding author: NBrent Faught, Professor of Epidemiology, Department of Health Sciences and Graduate Program Director for the Master of Public Health degree program, Brock University, Canada

How to cite this article: Nickolas L, Samantha P, Alex L, Mitchell I and Brent E F.. The Mediating Role of Perceived Scholastic Competence in the Relationship between Motor Coordination and Academic Performance. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil, 2021; 8(1): 555728. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2021.08.555728

Keywords:Developmental coordination disorder; Children; Physical activity; Neurological deficits

Introduction

The motor skill capabilities of a person are highly influenced by the motor learning they encounter across their lifespan through experience or specific practice [1]. However, there is a condition known as Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) that affects a small subset of children, resulting in attenuation of learning and compromised motor coordination when performing everyday tasks [2]. More specifically, children with DCD have motor coordination difficulties, and may have reached their motor related developmental milestones later than other healthy children. DCD can clinically present with difficulties in fine, as well as gross motor movements, which has consequences on their academic performance or activities of daily living. Importantly, these coordination difficulties are not a result of another pre-existing disease or pathology [3]. The incidence rate of DCD in children is believed to be relatively high, with 6-10% of the pediatric population having demonstrable obstacles with participation in physical activity [4-8]. In addition, it has been suggested that children who experience challenges with motor coordination as a result of DCD may not see improvements as they age [2,4]. The presence of DCD causes challenges in daily activities such as difficulty tying shoelaces, handwriting, and participating in physical activity [2,9]. Further, children affected by DCD may suffer ridicule from their classmates as their motor impairments are observable by others [2,10].

While the motor impairments associated with DCD have been shown to create difficulties for children in the classroom [11-13] recent evidence has revealed that the physical fitness of a child with poor motor proficiency is not a significant contributor to their academic performance [14]. Within the classroom, it is difficulties with handwriting that often limit scholastic participation in courses that require a significant amount of written work [11,15]. As a result, students affected by DCD are at risk of developing a poor sense of scholastic or cognitive competence because of lower grades [16]. Therefore, it is understandable that impairments in physical capabilities are thought to be associated with a child’s perceived cognitive and scholastic competence given age-specific environmental demands.

Importance of the problem and relevant research

Smits-Engelsman et al. [17] considered three primary hypotheses that might explain the motor difficulties observed in children with DCD: general slowness, limited capacity, and motor control mode. One common observation, with respect to general slowness, is that children with DCD are overall delayed in their performance of motor tasks [18]. Similarly, research has found that temporal processing impairment could account for some perceptual-motor and scholastic symptoms often associated with learning disorders [19]. Thus, children with DCD are likely to need more time to decide which movement is most appropriate for a given task [17]. Furthermore, the presence of motor coordination difficulties in children results in poorer performance on most measures of information processing, which would be a limiting factor in children with DCD [11,20]. With fewer resources available for parallel processing, planned movements could be compromised under high levels of cognitive load, which would support the limited capacity hypothesis. A third possibility is that the movement difficulties of children with learning disabilities reflect a reduced ability to automate motor skills [17]. This leads us to believe that children with DCD will demonstrate a reduced ability to transfer information from their minds to written words in a timely manner.

Within the last 20 years, graphonomic research has revealed important contributions to the understanding of fine motor control, motor development, and movement disorders [21]. In particular, the analysis of performance in handwriting and drawing tasks has been used to highlight neurological deficits affecting hand movements [22-24], as well as motor coordination difficulties in DCD [25-29]. Studies indicate that at least half of all children with a learning disability, or attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder are comorbid with DCD [18,30,31]. Thus, the difficulties in performing motor tasks experienced by individuals with DCD will only be exacerbated by the presence of a concomitant learning disability [18].

Relevant research to the study

Throughout their school years, children receive a great deal of comparative information about their capabilities from grading practices and teachers’ evaluations of their academic performances [32]. Ongoing comparative evaluations serve as an influence on a student’s sense of competence and self-efficacy with respect to academic performance. The amount of perceived self-efficacy has a significant impact not only on academic performance, but also on the student’s willingness to complete an academic task, as well as their self-motivation to improve where necessary. Prior literature demonstrates that children with a higher self-perceived sense of competence are more likely to attempt to perfect their cognitive abilities compared to those with the same level of cognitive skill, but a lower perceived sense of competence [33,34]. Cognitive development and function are largely dependent on a person’s writing literacy, which is mediated by their perception of selfefficacy. Enhancement of perceived writing efficacy by instruction has shown to increase levels of perceived self-efficacy for academic activities, personal standards for quality of writing, and academic goals [35]. Additionally, children with a high sense of self-efficacy behave more pro-socially, are more popular, and experience less rejection by their peers [36]. Thus, characteristics of children with DCD including poor self-efficacy, physical competence, and scholastic competence, would conceivably influence academic performance. To date, no research has examined the degree to which perceived scholastic competence influences academic performance in children with and without developmental coordination disorder. The primary objective of this study was to examine the mediating role of perceived scholastic competence in the relationship between motor coordination and academic performance in grade 6 children with and without developmental coordination disorder.

Materials and Methods

Research design

This nested case-control design was an ancillary study as part of a larger prospective cohort by the Physical Health Activity Study Team (PHAST); a 2-phase longitudinal investigation. Phase one was conducted between September 2004 and June 2007. During this phase, 2519 children from an original sample of 3030 grade four students (75 of 90 schools) agreed to participate in bi-annual school-based health assessments. Phase two was conducted between September 2007 and June 2010 on the same cohort of students. This research phase involved an annual school-based health assessment as well as a nested case-control laboratorybased assessment that formed the design foundation for this study. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from Brock University and the District School Board of Niagara. All children were required to provide informed consent in order to participate in both school and laboratory-based assessments. Furthermore, PHAST required corresponding informed consent from the child’s parent or guardian to participate in both school and laboratorybased assessments.

Participant selection

The original phase one of the PHAST longitudinal study included a surveillance sample of 2519 participants from September 2004 to June 2007. The second phase of the PHAST longitudinal study continued surveillance of 1785 of the original students (71% consent rate) from July 2007 to June 2010. Of these students, 963 (54% response rate) expressed interest in being contacted by telephone to participate in a laboratory-based component of the PHAST. A total of 124 grade 6 students were contacted by telephone who had previously been identified in phase one with suspected DCD by scoring in the lowest 10th percentile in motor coordination by the short form of the Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency (BOTMP-SF) [37]. Exclusion criteria in this study included an individual’s intelligence quotient below average (SD=2) when compared to same age peers. A total of 67 of these children (31 females and 36 males) agreed to participate in the laboratory-based component of the PHAST (54% consent rate) and served as the cases for our study. Control subjects who scored above the 10th percentile on BOTMP-SF and matched for age (within 3 months), gender, and school proximity were contacted by telephone to provide assent to participate in this case-control study. Grade six students were chosen to control for course subjects being taught while completing the EQAO standardized test for a second time.

Measure of motor coordination

All subjects were evaluated for motor coordination by a certified pediatric occupational therapist using the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd Edition (mABC-2). The mABC-2 is the most frequently used standardized motor test to screen for children with DCD [38] and is considered both reliable and valid [39,40]. Regardless of each subject’s previous BOTMPSF score from phase one of the PHAST study, motor competence assessment of gross and fine motor coordination was evaluated in all subjects. The mABC-2 consists of eight task items grouped under three headings: Manual Dexterity, Aiming and Catching, and Balance. For each item, a standard score was provided. Parent or guardian were not present during the mABC-2 assessment. From each of these standard scores, a cumulative age adjusted score and percentile score was generated [41]. Children with a score at or below the 15th percentile were identified as having DCD. The pediatric occupational therapist was blinded to the child’s BOTMP-SF score. Nevertheless, a full assessment of all DSM-V criteria required to confirm a diagnosis of DCD was not possible. Specifically, the current study was not able to determine if the motor skills deficit significantly and persistently interferes with activities of daily living relative to the subject’s chronological age and influenced their academic productivity, prevocational activity, leisure, and play. Considering this limitation, the researchers of this study decided to use the term suspected DCD (s-DCD) to describe subjects below the 15th percentile for the mABC-2 score.

Measure of intellectual ability

Intellectual ability was assessed using the KBIT-2 [42] to verify that motor coordination was not discrepant with cognitive development [43]. The KBIT-2 is a brief and reliable measure of intelligence that does not require administration by psychologists and can be performed by a certified occupational therapist [42]. The test also provides a measure of the general level of a child’s intellectual ability.

Measure of scholastic competence

The PHAST administered Harter’s Perceived Competence Scale for Children in the participant’s homeroom class during the school-based assessment [44]. Research assistants explained the scale, guided students to completion, and verified the completeness of each questionnaire. The Harter scale contained 32 items representing six domains, including scholastic competence (6 items), social acceptance (6 items), athletic competence (5 items), physical appearance (5 items), behavioral conduct (5 items) and general domain of global self-worth (5 items). For the purpose of this investigation, a composite score ranging from 6-24 for scholastic competence using the following six questions was utilized.

1. (Harter Question 1): Some kids feel that they are very good at their schoolwork, but other kids worry about whether they can do the work assigned to them.

2. (Harter Question 7): Some kids feel like they are just as smart as other kids their age, but other kids aren’t so sure and wonder if they are as smart

3. (Harter Question 13): Some kids are pretty slow in finishing their schoolwork, but other kids can do their schoolwork quickly.

4. (Harter Question 19): Some kids often forget what they learn, but other kids can remember things easily.

5. (Harter Question 25): Some kids do very well at their class work, but other kids don’t do very well at their class work.

6. (Harter Question 31): Some kids have trouble figuring out the answer in school, but other kids almost always can figure out the answer.

Harter [44] previously verified the validity and reliability of the Harter scale through factor analysis of the six domains separately. Each domain demonstrated discriminating factors, indicating that the Harter scale is an effective tool in differentiating among the six domains in children [44].

Measure of academic performance

District School Board of Niagara provided the final grades for 10 grade 6 courses including, three English competencies (oral/ visual comprehension, reading, writing), Health and Physical Education, five Math operations (data/probabilities, numbers, patterns/algebra, geometry/spatial, measurement), Science and Technology, three Second Language competencies (oral, reading, writing), Social Studies, Visual Arts, Drama and Dance, Music, and three Education Quality and Accountability Office scores (math, reading, writing). Access to data for Geography, Design and Technology, Choices and Changes, and History were unavailable.

Statistical analyses

Independent t-tests and corresponding descriptive statistics were used to compare differences between s-DCD and control groups for subject age, mABC-2 score, K-BIT score, Harter total and sub-scale scores, and all final grades per academic subject. To address the study’s objective, multiple linear regression with a progressive adjustment strategy was incorporated using two models. Model one examined the main effect of motor coordination as measured by mABC-2 on academic performance using overall grade average. Model 2 determined if the relationship between mABC-2 score and academic performance was influenced by scholastic competence. More specifically, a reduction in the unstandardized b-coefficient in model 2 for mABC-2 score would suggest that diminished perceived scholastic competence mediates the initial relationship between motor coordination and academic performance. Both models controlled for age, gender, and intellectual ability. In the event of multicollinearity (variance inflation factor > 10), independent variables were zeroed. Level of significance for all statistical analyses was set at α=0.05.

Results

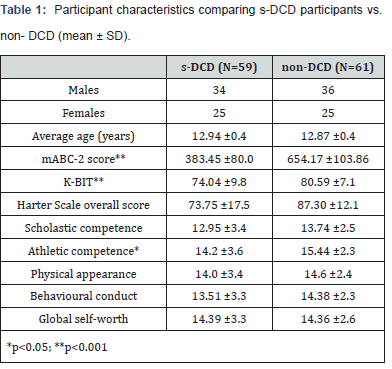

The study initially included 126 subjects: 63 children with s-DCD and 63 controls (non-DCD) matched for age within three months, gender, and school proximity. Due to incomplete data, the final sample for this study included 120 subjects (59 s-DCD cases, 61 healthy controls). Table 1 outlines the descriptive statistics for the s-DCD and control groups. Since cases and controls were matched on age, no significant difference existed. In accordance with DSM-V diagnostic criteria, children with s-DCD scored significantly lower on the mABC-2 assessment than non-DCD subjects. Children with s-DCD demonstrated significantly lower scores on the K-BIT scale of intelligence (p<0.01) and Harter Scale sub-component of ‘athletic competence’ (p<0.05) compared to matched controls. No significant differences were identified between groups within the other Harter Scale sub-components (i.e., scholastic, physical appearance, behavioral conduct, and global self-worth) or overall Harter Scale (p>0.05).

Academic performance

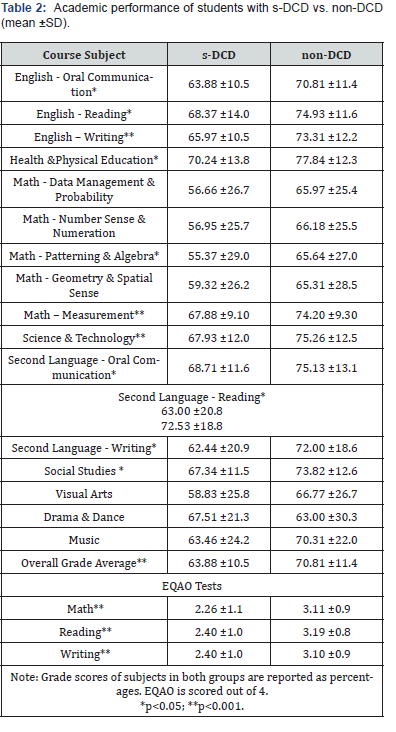

Table 2 outlines the comparative statistics of subjects with s-DCD versus matched control subjects for academic performance in each grade 6 course subject, overall grade average, and EQAO course grades in math, reading, and writing. Final grades were reported for all grade 6 course subjects except Geography, History, Choices and Changes, and Design and Technology. Students with s-DCD demonstrated significantly lower final course grades in all English components (oral communication, reading, writing), Health and Physical Education, Science and Technology, all Second Language components (oral communication, reading, writing), Social Studies, and two components of Math (patterning and algebra, measurement) compared to control subjects (p<0.05). Conversely, no significant differences in final course grades were demonstrated in three Math components (data management and probability, number sense and numeration, and geometry and spatial sense), Visual Arts, Drama & Dance, and Music (p>0.05). EQAO scores for math, reading, and writing were significantly lower in students with s-DCD compared to control subjects (p<0.01). Finally, overall grade average in all grade 6 courses was significantly lower in students with s-DCD (63.88 ±10.5) compared to non-DCD (70.81 ±11.4) matched control subjects (p<0.01).

Regression of academic performance on s-DCD and scholastic competence

Table 3 reports the results of the multiple linear regression analysis. The overall average for all courses served as our outcome measure of academic performance. All assumptions for independence of residuals, multicollinearity, and normality were met before continuing with analysis. In Model 1, after controlling for age, gender, and K-BIT score, the main effect of mABC-2 on the overall average was positive and significant (p<0.05). The mediating influence of perceived scholastic competence was tested in Model 2 and was statistically significant (p<0.01). The explained variance increased substantially from model 1 (R2=15%) to model 2 (R2=25.3%). The controlling variables of age, gender, and K-BIT were not significant in either models (p>0.05). Finally, the descending shift in the mABC-2 unstandardized b-coefficient from model 1 to model 2 indicated that perceived scholastic competence partially mediated the original relationship between mABC-2 and academic performance by 15%.

Discussion

This study evaluated the relationship between motor coordination, perceived scholastic competence, and academic performance in 120 grade six children with and without DCD. It was hypothesized that perceived scholastic competence would be a significant mediating factor in the relationship between motor coordination and academic performance. Theoretically, as the level of motor coordination in a child decreases, it leads to lower levels of perceived scholastic competence and increasingly poorer performance in school. However, independent t-testing revealed no significant difference between children with and without DCD on perceived scholastic competence while multiple linear regression analysis showed a significant mediating effect on academic performance. Several factors may explain these findings.

In a study investigating the psychosocial implications of impaired motor coordination in children and adolescents with and without DCD, Skinner and Piek [45] found that only younger children (8-10 years) with DCD demonstrated a lower perception of scholastic competence, and that perception of scholastic performance was not significantly different between adolescents aged 12-14 years with and without DCD [45]. The mean age of the s-DCD and non-DCD groups fell within this age range, which may explain why independent t-testing in our study revealed no significant difference in perceived scholastic competence between children with and without DCD.

Research on self-efficacy and expectancy beliefs has shown that the level of perceived scholastic competence in a child varies depending upon specific academic subject matter [46]. Studies have demonstrated that perceived competence can vary on whether a child is asked to solve a math problem [47,48] or perform a writing or reading assignment [47, 49]. Since the present study did not specify individual academic subject matter when measuring perceived scholastic competence, it is possible that a child’s overall academic versus course-specific perceived scholastic competence may vary.

Academic performance and developmental coordination disorder

In our study, children with s-DCD performed significantly worse than their healthy peers in the majority of course disciplines. The only course subjects that indicated no difference between study groups included the Arts (Music; Drama and Dance; Visual Arts) as well as three categories of Mathematics (Data Management and Probabilities; Number Sense and Numeration; Geometry and Spatial Sense).

These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that children with DCD have significantly greater challenges performing well in the classroom compared to children without impaired motor coordination [12,50]. While Dewey et al. [12] studied the effects of DCD on the attention, reading, writing, and spelling abilities of children, this is the first study to examine final grades in most of all course disciplines, as well as standardized provincial EQAO grades.

As expected, courses that require significant fine motor coordination for scripting (i.e., English, French, and Social Studies), or expect efficiency in gross motor coordination (i.e., Health & Physical Education), resulted in children with s-DCD performing significantly worse than their healthy peers. Research has shown that performing a large amount of script within a specific time frame is particularly difficult for children with motor coordination challenges as they take a significantly longer time per stroke compared to healthy controls [15]. This would explain why children with s-DCD in our study performed significantly worse in courses with large writing demands (English, French, Social Studies). Further, it has been found that 30-60% of a child’s school day is focused on fine motor activities with an emphasis on writing tasks [51], demonstrating the negative impact motor coordination difficulties can have on overall academic performance.

In addition to the writing deficiencies experienced by children with s-DCD within the language classes, our study also found that these children performed worse than their healthy peers in both the oral communication and reading components of these courses. It has been shown that scripting is very difficult for a child with DCD [52]. Due to these challenges with scripting, poor performance may result in negative feedback leading to children with DCD developing a low level of perceived competence in their ability to script. Therefore, it is possible that poor performance in the writing components of language classes leads to children with DCD developing poor perceived competence in their language skills as a whole.

Science & Technology course content does not require students to script large amounts of written material nearly as often as in the language courses. However, students are required to create sample drawings and/or diagrams to carry out course expectations with respect to experimental solution, as well as designing, building, and testing a device [53]. Nevertheless, drawing and building of experimental devices can be especially difficult for children with DCD as they exhibit diminished fine motor control [28]. Concerning mathematics specifically, our study found mixed results. Since significance was clear in some components (Measurement; Patterning & Algebra) and nearly significant in others (Number Sense & Numeration; Data Management & Probabilities), it was thought that children with s-DCD generally have greater challenges in most categories of Mathematics compared to their healthy peers. However, Smits- Engelsman et al. [17] suggested that children with DCD may not be completely disadvantaged in math activities that are discrete in nature such as measurements or drawing angles with protractors, as these fine motor activities do not pose as great of a challenge.

Children with s-DCD demonstrated comparable final grades relative to their healthy peers in Visual Arts and Music, as well as slightly better grades in Drama & Dance. The physical demands and coordination required for dancing and dramatic movement place a large emphasis on gross motor coordination, which should create significant difficulties for children with s-DCD. However, the Ontario Ministry of Education [53] emphasizes that student expectation in Dance & Drama is to develop personal movement vocabularies that communicate their feelings, ideas, and understandings of movement. The subjective evaluation of teachers on each student’s individual use of movement and elements of dance rather than rote repetition or learned choreographed movements may explain our findings in these courses. Further, subjective evaluation may allow children with coordination challenges greater freedom of personal expression rather than an emphasis on the need for comparison to their coordinated peers. This factor in addition to a lack of emphasis on a rigid pedagogical expectation by their teacher, may in combination result in better performance. The aforementioned phenomenon has been shown in previous research on the influence of social comparisons, demonstrating that individuals observing themselves as being surpassed by their peers results in a diminished sense of self-efficacy and a progressively impaired performance [54,55].

Subjective evaluation of students is not specific to Dance, as teachers of Visual Arts use their professional judgement to evaluate the course expectations that should be used to grade achievement of students [53]. While the involvement of fine motor tasks such as drawing, painting, sculpting, printmaking, and architecture in Visual Arts may be challenging for children with DCD, the lack of objective grading criteria, and the ability to evaluate student performance without comparison to their peers may foster a more non-threatening atmosphere that could motivate children with DCD in the discipline of fine and performing arts.

Final grades for Music class were considered the same for children with and without s-DCD. Music class is designed to teach students practical skills such as playing an instrument or singing, as well as the opportunity to explore music critically through emotion and reason [53]. The opportunity to respond to, analyze, and interpret music allows children to express their thoughts and feelings. Therefore, like Visual Arts and Dance, Music class is reflective of an environment that fosters free thinking and expression of feelings and emotions in response to musical pieces. Within the grade six arts, the potential exists for less emphasis on scripting or choreographed movements and greater emphasis on subjective evaluation by the teacher on expressive movement and creative thoughts by the student [53]. However, the degree in which these factors influence the academic success of a child with DCD is not well understood and requires further examination.

Limitations

Data missing for Geography, Design & Technology, Choices & Changes, and History limited our ability to evaluate scholastic performance for all course disciplines. Thus, the overall grade average is not entirely reflective of the academic performance differences between grade six students with and without s-DCD. Second, evaluation of perceived scholastic competence assessed belief and self-efficacy in all course disciplines in a general sense, rather than each individual course topic. Future investigations should consider accounting for class specific subject matter to provide a more accurate measurement of perceived scholastic competence. Third, validity of final grades may be limited due to teacher variation and bias during the evaluation process. Teacher evaluation tools are not as structured and standardized as the EQAO examinations and are therefore subject to disparity. Finally, the cross-sectional data for academic performance in grade six prohibited the researchers from establishing any level of causality. A longitudinal investigation of academic performance across several grades with corresponding measures of motor coordination and perceived scholastic competence would provide a greater understanding of any causal influence that may exist.

Conclusion

Perceived scholastic competence mediated the relationship between motor coordination and a child’s academic performance by 15%. Considering that children with DCD will have this condition through secondary and post-secondary education [4,56], it is expected that the impact of perceived scholastic competence on an individual with DCD will impede their scholastic performance throughout their academic careers. By applying differentiated instruction to children with DCD, such as adding an opportunity for the child to work through problems and assignments verbally while reducing the number of written requirements, teachers could prevent reductions in perceived scholastic competence in children with DCD. Due to their slower writing speed as a result of longer stroke times [15], a reduced written workload could limit the anxiety experienced by a child with DCD to complete an assigned task in the allotted time. Still, some course disciplines in the arts demonstrate promise in which children with DCD may experience scholastic success. Continued academic success in these courses may contribute to elevating the scholastic confidence in children with DCD despite fine and gross motor challenges.

Further, research on DCD and perceived scholastic competence could examine the influence of instructional feedback on a child’s self-efficacy. It is possible that teachers using strategies to encourage children through external feedback and verbal persuasion, rather than challenging them, could enhance performance within the classroom. Research has shown that strategies used by educators which include external feedback and verbal persuasion may have a significantly positive impact on a students’ motivation and perceived abilities in the subject matter [57].

Lastly, technological advancements in education could offer children with DCD the opportunity to express their knowledge using voice recognition software as an alternative to written work. While perceived scholastic competence plays a significant role in a child’s academic performance, research on the most effective methods to attenuate or prevent a child’s competence from suffering could provide teachers with the best methods of approaching the education of children with DCD. If children with DCD are provided with the necessary tools, they will discover a direct relationship between their effort and achievement.

References

- Ehsani F, Abdollahi I, Bandpei MAM, Zahiri N, Jaberzadeh S (2015) Motor learning and movement performance: older versus younger adults. Basic and clinical neuroscience 6(4): 231-238.

- Cairney J, Hay J, Faught BE, Corna LM, Flouris AD (2006) Developmental coordination disorder, age and play: a test of the divergence in activity-deficit with age hypothesis. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 23(3): 261-276.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Bouffard M, Watkinson EJ, Thompson LP, Dunn JLC, Romanow SK (1996) A test of the activity deficit hypothesis with children with movement difficulties. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 13(1): 61-73.

- Cantell MH, Smyth MM, Ahonen TP (1994) Clumsiness in adolescence: Educational, motor, and social outcomes of motor delay detected at 5 years. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 11(2): 115-129.

- Faught BE, Hay JA, Cairney J, Flouris A (2005) Increased risk for coronary vascular disease in children with developmental coordination disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health 37(5): 376-380.

- Okely AD, Booth ML, Patterson JW (2001) Relationship of physical activity to fundamental movement skills among adolescents. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 33(11): 1899-1904.

- Ulrich BD (1987) Perceptions of physical competence, motor competence, and participation in organized sport: Their interrelationships in young children. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 58(1): 57-67.

- Zwicker JG, Suto M, Harris SR, Vlasakova N, Missiuna C (2018) Developmental coordination disorder is more than a motor problem: children describe the impact of daily struggles on their quality of life. British journal of occupational therapy 81(2): 65-73.

- Cairney J, Hay J, Faught B, Mandigo J, Flouris A (2005) Developmental coordination disorder, self-efficacy toward physical activity, and play: Does gender matter? Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 22(1): 67-82.

- Bernardi M, Leonard HC, Hill EL, Botting N, Henry LA (2018) Executive functions in children with developmental coordination disorder: a 2‐year follow‐up study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 60(3): 306-313.

- Dewey D, Kaplan BJ, Crawford SG, Wilson BN (2002) Developmental coordination disorder: associated problems in attention, learning, and psychosocial adjustment. Human Movement Science 21(5-6): 905-918.

- Wocadlo C, Rieger I (2008) Motor impairment and low achievement in very preterm children at eight years of age. Early human development 84(11): 769-776.

- Alexander R, Hay JA, Liu J, Faught BE, Engemann J, Cairney J (2015) The influence of aerobic fitness on the relationship between academic performance and motor proficiency. Universal Journal of Public Health 3(4): 145-152.

- Rosenblum S, Livneh-Zirinski M (2008) Handwriting process and product characteristics of children diagnosed with developmental coordination disorder. Human Movement Science 27(2): 200-214.

- Klein S, Magill-Evans J (1998) Perceptions of competence and peer acceptance in young children with motor and learning difficulties. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics 18(3-4): 39-52.

- Smits-Engelsman B, Wilson P, Westenberg Y, Duysens J (2003) Fine motor deficiencies in children with developmental coordination disorder and learning disabilities: An underlying open-loop control deficit. Human Movement Science 22(4-5): 495-513.

- Jongmans M J, Smits-Engelsman BC, Schoemaker MM (2003) Consequences of comorbidity of developmental coordination disorders and learning disabilities for severity and pattern of perceptual—motor dysfunction. Journal of learning disabilities 36(6): 528-537.

- Habib M (2000) The neurological basis of developmental dyslexia: an overview and working hypothesis. Brain 123(12): 2373-2399.

- Wilson PH, McKenzie BE (1998) Information processing deficits associated with developmental coordination disorder: A meta-analysis of research findings. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and allied disciplines 39(6): 829-840.

- Van Gemmert AW, Teulings HL (2006) Advances in graphonomics: studies on fine motor control, its development and disorders. Human Movement Science 25(4-5): 447-453.

- Dounskaia N, Van Gemmert AW, Leis BC, Stelmach GE (2009) Biased wrist and finger coordination in Parkinsonian patients during performance of graphical tasks. Neuropsychologia 47(12): 2504-2514.

- Popovic MB, Dzoljic E, Kostic V (2008) A method to assess hand motor blocks in Parkinson's disease with digitizing tablet. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine 216(4): 317-324.

- Van Gemmert A, Teulings HL, Contreras-Vidal JL, Stelmach G (1999) Parkinsons disease and the control of size and speed in handwriting. Neuropsychologia 37(6): 685-694.

- Engel-Yeger B, Nagauker-Yanuv L, Rosenblum S (2009) Handwriting performance, self-reports, and perceived self-efficacy among children with dysgraphia. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 63(2): 182-192.

- Hamstra-Bletz L, Blöte AW (1993) A longitudinal study on dysgraphic handwriting in primary school. Journal of learning disabilities 26(10): 689-699.

- Rosenblum S, Parush S, Weiss PL (2003) Computerized temporal handwriting characteristics of proficient and non-proficient handwriters. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 57(2): 129-138.

- Smits-Engelsman BC, Niemeijer AS, van Galen GP (2001) Fine motor deficiencies in children diagnosed as DCD based on poor grapho-motor ability. Human Movement Science 20(1-2): 161-182.

- Smits-Engelsman BC, Van Galen GP (1997) Dysgraphia in children: Lasting psychomotor deficiency or transient developmental delay? Journal of experimental child psychology 67(2): 164-184.

- Kaplan BJ, Wilson BN, Dewey D, Crawford SG (1998) DCD may not be a discrete disorder. Human Movement Science 17(4-5): 471-490.

- Sugden D, Wann C (1987) The assessment of motor impairment in children with moderate learning difficulties. British Journal of Educational Psychology 57(2): 225-236.

- Marshall HH, Weinstein RS (1984) Classroom factors affecting students’ self-evaluations: An interactional model. Review of educational research 54(3): 301-325.

- Schunk DH (1996) Goal and Self-Evaluative Influences During Children's Cognitive Skill Learning. American Educational Research Journal 33(2): 359.

- Zimmerman BJ, Schunk DH, DiBenedetto MK (2017) The role of self-efficacy and related beliefs in self-regulation of learning and performance. In AJ Elliot C S Dweck, D S Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (pp. 313–333). The Guilford Press.

- Zimmerman BJ, Bandura A, Martinez-Pons M (1992) Self-motivation for academic attainment: the role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. use of the Children's multidimensional self-efficacy scales 29: 663-676.

- Bandura A (1993) Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist 28: 117-148.

- Bruininks RH (1978) Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency: American Guidance Service Circle Pines, MN.

- Wilson PH (2005) Practitioner review: approaches to assessment and treatment of children with DCD: an evaluative review. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 46(8): 806-823.

- Crawford SG, Wilson BN, Dewey D (2001) Identifying developmental coordination disorder: consistency between tests. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics 20(2-3): 29-50.

- Tan SK, Parker HE, Larkin D (2001) Concurrent validity of motor tests used to identify children with motor impairment. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 18(2): 168-182.

- Henderson SE, Sugden DA, Barnett AL (2007) Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2: MABC-2: Pearson Assessment.

- Kaufman A (2004) Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. 2nd. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing.

- Sugden D, Chambers M (2007) Stability and change in children with developmental coordination disorder. Child: care, health and development 33(5): 520-528.

- Harter S (1982) The perceived competence scale for children. Child development: 87-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1982.tb01295.x.

- Skinner RA, Piek JP (2001) Psychosocial implications of poor motor coordination in children and adolescents. Human Movement Science 20(1-2): 73-94.

- Bong M (2001) Between-and within-domain relations of academic motivation among middle and high school students: Self-efficacy, task value, and achievement goals. Journal of educational psychology 93(1): 23-24.

- Agustiani H, Cahyad S, Musa M (2016) Self-efficacy and self-regulated learning as predictors of students’ academic performance. The Open Psychology Journal 9(1): 1-6.

- Pajares F (1996) Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of educational research 66(4): 543-578.

- Shell DF, Murphy CC, Bruning RH (1989) Self-efficacy and outcome expectancy mechanisms in reading and writing achievement. Journal of educational psychology 81(1): 91.

- Leonard HC, Hill EL (2015) Executive difficulties in developmental coordination disorder: methodological issues and future directions. Current Developmental Disorders Reports 2(2): 141-149.

- Piek JP, Baynam GB, Barrett NC (2006) The relationship between fine and gross motor ability, self-perceptions and self-worth in children and adolescents. Human Movement Science 25(1): 65-75.

- Prunty MM, Barnett AL, Wilmut K, Plumb MS (2016) The impact of handwriting difficulties on compositional quality in children with developmental coordination disorder. British journal of occupational therapy 79(10): 591-597.

- Ontario Ministry of Education (2007). The Ontario Curriculum: Science and Technology, Grades 1-8. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/scientec18currb.pdf (accessed on 17/12/2020).

- Bandura A (1993) Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist 28(2): 117-148.

- Bandura A (2010) Self‐efficacy. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology: 1-3.

- Hay JA, Hawes R, Faught BE (2004) Evaluation of a screening instrument for developmental coordination disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health 34(4): 308-313.

- Wright PM, Ding S, Li W (2005) Relations of perceived physical self-efficacy and motivational responses toward physical activity by urban high school students. Perceptual and motor skills 101(2): 651-656.