High-Leverage Instructional Practices for Students with Autism and Mild Disabilities in Traditional and Remote Learning Settings

McKeithan G K1*, Rivera M O2 and Robinson G G2

1Department of Special Education, University of Kansas, USA

2Department of Educational Leadership and Specialties, University of North Carolina Pembroke, USA

Submission:February 01, 2021;Published:February 16, 2021

*Corresponding author:Glennda K McKeithan, University of Kansas Special Education Department, USA

How to cite this article:McKeithan K G, Rivera M O, Robinson G G. High-Leverage Instructional Practices for Students with Autism and Mild Disabilities in Traditional and Remote Learning Settings. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil, 2021; 7(4): 555719. DOI:10.19080/GJIDD.2021.07.555719

Abstract

Meeting the needs of students with autism and mild disabilities effectively in traditional and remote settings must be an individualized, purposeful, and data-driven process [1]. Learning to implement a core foundation of easy-to-use evidence-based instructional practices can help teachers across content areas develop a core foundation of “go to” practices which can potentially benefit all students with and without disabilities [2]. The High-Leverage Practices (HLPs) recently identified by the Council for Exceptional Children and the CEEDAR Center at the University of Florida [3] can help educators to target their students’ most significant skill deficits and, subsequently, develop and deliver instructional programming that may help students develop to their fullest potential. The 22 identified HLPs are multifaceted, evidence-based practices. The HLPs are divided into four core categories: assessment, collaboration, instruction and social-emotional/behavioral practices. The present article focuses on practical applications of 12 of the 22 HLPs related to instructional practices and are further categorized into three guiding principles for teachers: (1) Plan with a purpose, (2) Teach for success, and (3) Actively engage learners. The purpose of the article is to discuss the application of these HLPs in traditional and remote settings to potentially improve academic and social-behavioral outcomes for students with autism and mild disabilities [4]

Keywords: High-leverage practices; Autism; Mild disabilities; Instructional strategies; Teacher practices; General education; Special education; Remote learning; Online learning; Distance learning

Introduction

Teacher educators, special and general teachers face complex challenges related to meeting the instructional needs of students with autism and mild disabilities in both traditional and remote settings. Often, these students with disabilities (SWD) struggle to meet academic and social-behavioral demands in varied educational settings. A current example is the debated decision to return to traditional face-to-face vs. online instruction next 2020-2021 school year in the midst of an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic [5]. While stressed by a myriad of logistic and financial factors, school administrators and institutions of higher education examine the pros and cons of each delivery method, still uncertain of how this decision will affect the academic achievement and health of students, teachers and school communities in general. In the public schools, over 7 million students ages 6-21 who are eligible for special education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), over 700,000 students with 504 plans, nearly 775,000 children ages 3-5 who attend preschool under IDEA and over 400,00 children ages 0-3 who are served in programs under Part C of IDEA in public schools will be impacted by this decision (OSERS, 2020). These children, their families and teachers must remain a vital priority and have the tools they need to succeed, especially in online instruction platforms.

Given the Least Restrictive Environment provision of IDEA, SWD are often served in general education. Implementing evidence-based practices (EBPs) when planning and delivering instruction for SWD can positively affect achievement. Unfortunately, knowing which EBPs to use across settings with learners who may have varied developmental, cognitive and social-behavioral needs can be a challenge. Recently, the Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability and Reform (CEEDAR) and the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) published the High-Leverage Practices in Special Education These high-leverage practices (HLPs) are multifaceted, evidencebased practices that can be used to plan and deliver instruction that promotes academic and social-behavioral achievement for SWD across subjects and settings [7]. The 22 HLPs are divided into four core aspects: assessment, collaboration, instruction and social-emotional/behavioral practices [3]. The present study focuses on the practical applications of the 12 instruction HLPs designed to improve outcomes and maximize instructional time in inclusive settings. Understanding and utilizing the instructional HLPs can help teachers hone content pedagogy skills as they purposefully consider information from multiple sources to clarify what to teach (content standards), and link content mastery to learner (interests, strengths and needs, backgrounds) to develop specific learning goals. Once targeted (long and short term) goals are established, the instruction HLPs can help educators to assess progress consistently, make data-driven decisions during instructional delivery, and implement strategies (teacherled, peer-assisted, student-regulated, and technology-assisted practices) to promote academic and social-behavioral success [3]. For the purposes of this article, the interconnected nature of the instructional HLPs is categorized into three guiding principles for teachers. Table 1 summarizes the categories and related HLPs.

Plan with a Purpose

Planning and delivering relevant and meaningful learning experiences for SWD according to their needs and curriculum demands (regardless of the setting) is a multifaceted, complex but worthy endeavor. Effective planning is considered a cornerstone of the teaching-learning system [8]. The HLPs included in this category are: HLP 11: Identify and prioritize long and short-term goals, HLP 12: Systematically design instruction toward a specific learning goal, HLP 13: Adapt curriculum tasks and materials for specific learning goals, HLP 14: Teach cognitive and metacognitive strategies to support learning and HLP 17: Use flexible grouping.

Identify and Prioritize Long and Short-Term Learning Goals (HLP 11)

Research consistently notes the importance of making learning relevant through the use of long- and short-term goals tightly connected to grade level standards as well as student interests, strengths and needs [9]. Educators, students, and other stakeholders must regularly identify and comprehend varied types of goals (assessment goals, curriculum goals, schoolbased goals, county, state and even national goals) and integrate these goals into instructional planning. Instructors who see and understand “the big picture” and overall reason/thinking behind the goals are more likely to internalize the significance of the goals and subsequently “sell” their relevance to learners. Meaningful instruction must be based on consistent, ongoing assessed needs of students as they progress towards meeting goals [10]. Teachers must consider curriculum-related strengths and needs, IEP goals, as well as formal and/or informal assessment measures to design instruction. Effective teachers integrate student needs with deep understanding of curriculum content [9]. Commercial and readymade lesson plans, pacing guides and curriculum resources may inadvertently shift the focus of the lesson to task completion, and teachers may take for granted students understand what the learning goals are and how goals are connected with needed skills [8]. Communicating goals to students in conjunction with a connection to interests (why/how goal mastery is connected to personal goals) has the potential to enhance motivation [9]. Furthermore, recognizing the need to task-analyze goals by breaking instructional presentation and tasks into small “chunks” can help to ensure students understand all steps and/ or foundational knowledge needed to progress towards goal mastery [3,11].

Systematically Design Instruction Toward a Specific Learning Goal (HLP 12)

Systematically designed instruction requires purposeful and sequential planning of instruction which consistently builds on previously learned constructs as students work towards meeting goals [12]. Using task analysis can help instructors to scaffold instruction that maximizes the potential students will acquire new learning across content and settings [13]. The primary components of this HLP include: 1) specific and measurable goals; 2) lessons which build on one another to move learners towards goals and 3) considering the learner’s perspective; integrate needed supports for learning [3]. Instructional presentation must help students learn concepts and skills that provide the foundation for more complex learning. Setting goals that are specific and measurable is a vital aspect of effective instruction, but ensuring the goals are realistic and achievable for individual learners as well as the entire group can be a challenge. Teachers must be careful not to let the needs of the group (to meet local, state or national benchmarks and standards) overweigh the needs of individual students [13]. Designing IEP goals which consider content standards as well as unique student interests’ strengths and needs is necessary to implement this HLP. Embedding consistent and varied assessment methodologies and progress monitoring tools can help educators to provide needed support (reteaching, supplemental activities) and adjust instruction according to student achievement [11]. Link goals with prior knowledge and help learners understand how and why goal mastery can positively impact achievement, long-term memory as well as higher order thinking and reasoning. Appropriately sequenced instruction should help learners see how each lesson “connects” with previous learning. For example, synthetic phonic approaches to teaching reading are systematic in that the most common letter sounds and syllable types are taught and practiced before moving on to more complex skills. The systematic acquisition of skills allows learners in the earlier stages of reading development to acquire mastery of these skills to decode more accurately and fluently [12]. Planning involves careful consideration of learning goals, what is involved in reaching the goals, and allocating time accordingly. Ongoing changes (epacing, examples) must occur throughout the sequence in alignment with ongoing achievement. Design lessons that start with reviewing prior knowledge and chunk learning so rigorous concepts and more difficult learning increases gradually. Teach multiple ways to solve problems and share knowledge and offer learners multiple opportunities to practice and obtain feedback as they build competence with a given skill [14].

Adapt Curriculum Tasks and Materials for Specific Learning Goals (HLP13)

Given the need for SWD to be served in the least restrictive environment, adapting curriculum tasks and materials to support students in meeting learning goals is essential. PL 94-142 includes a provision related to Adapting Supplementary aids and services (SAS) for SWD. Educators must modify curriculum demands and understand the distinction between accommodations and modifications. Modification changes what a student is taught or expected to learn [15]. Make purposeful choices about what and how important content is presented based on assessed needs which integrates meaningful tasks to help students achieve specific goals. Educators can use a variety of teaching strategies, technology, scheduling, individualized instruction, mastery learning, cooperative learning and/or individualized instruction to adapt tasks and materials. IEP teams regularly identify accommodations (changes how material is learned) and/ or modifications (changes what is taught or expected). Teach new concepts using a variety of presentation methods. Educators who help students see the big picture by connecting new learning with prior knowledge and future instruction can better support all learners [16].

Teach Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies to Support Learning (HLP 14)

Research has long supported the benefits of explicitly teaching students how to think by directing attention towards meaningful and specific learning goals. Instruction must be focused on teaching students to achieve learning outcomes. Creating a highly structured environment in which the content is supported by explanation, demonstration, practice can reinforce independent learning. Using teacher talk and repetition can help students to understand key concepts, attend to detail, connect ideas to prior knowledge and remember new material in association with varied experiences. Integrating self-regulation strategies into daily practice can help students develop organization and problem-solving skills as they learn to monitor thinking and adjust responses to instruction to ensure goal mastery [17, 18].

Use Flexible Grouping (HLP 17)

Peer mediated instruction and intervention is an EBP with the potential to benefit all learners. Flexible grouping of peers using heterogeneous and/or homogeneous groups can promote and reinforce learning for all students. The key to success with this HLP is purposeful planning of student interactions used in conjunction with proximity control and constructive student feedback [3]. Group roles and responsibilities must be explicitly taught, and students must be held accountable. Collaboration skills must be modeled and practiced so students understand how to feel comfortable engaging in academic discourse.

Teach academic discourse skill initially in conjunction with familiar content; remember it is easier to have a meaningful conversation when you feel confident about the topic). Learning environments must reinforce skills relevant to group work such as (1) time management (2) task analysis and planning (3) sharing/appreciating diverse perspectives/experiences (4) using effective communication skills to enhance understanding and solve complex problems (5) expectations require individual and group accountability related to achieving a common goal [19]. Helping students understand the benefits and skills needed to effectively collaborate groups as well as how to diplomatically give and accept constructive feedback is a skill needed to develop the collaborative problem-solving skills in the world of work and adult relationships. Use a variety of strategies to teach sound procedures and problem-solving skills which are consistently monitored and reinforced to sustain group performance [3,13]. Table 2 offers an overview of strategies to implement these HLPs in traditional and remote learning settings.

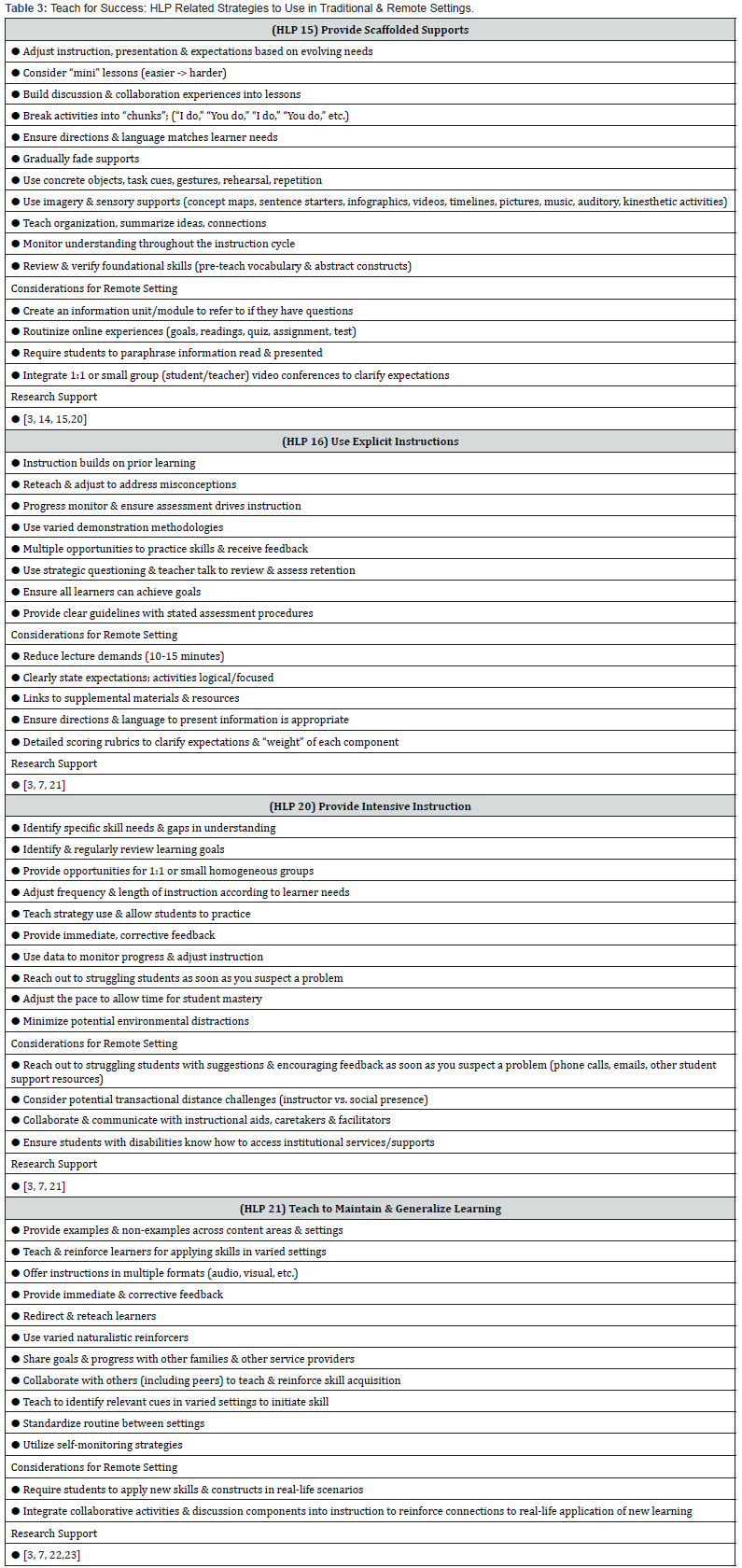

Teach for Success

The HLPs described in this category are essential components of successful instruction consistently referenced in the extant literature to be directly linked with positive achievement. Scaffolding must be incorporated as an explicit practice when designing intensive instruction needed to move learners towards independence and skill mastery across settings and content [3]. The HLPs described in this category are: (HLP 15) Provide scaffolded supports throughout the instructional cycle, (HLP 16) Use explicit instruction, (HLP 20) Provide intensive instruction, and (HLP 21) Teach students to maintain and generalize learning across time/settings.

Provide Scaffolded Support (HLP 15)

Employing scaffolded instruction encourages instructors to take into account the strengths and needs of learners, the challenging aspects of the instruction, and the developmental trajectory of the learning skills [20]. These temporary supports can be integrated into instructional delivery to help learners grasp an idea and master tasks when they cannot yet perform skills independently. In reaction to a child’s demonstration of independence, the scaffolding supports should be calibrated according to individual skill levels, and then gradually faded [14]. Scaffolded visual, verbal, and written supports are not content or skill specific, and they can be pre-planned or used as needed when students require assistance with skill acquisition. Integrated into daily educational practice, effective scaffolding can help to advance what a student already knows and maximize the potential a student is successful and working towards reaching their full potential [15].

Use Explicit (HLP 16) and Intensive (HLP 20) Instruction

Explicit instruction can help learners grasp new learning as teachers use varied instructional presentation methods and learning activities. Intensive instruction requires teachers to deliver instruction aligned with their knowledge of individual learning and behavioral needs. Explicit and intensive instruction helps students comprehend new content, problem solve and develop higher order thinking and reasoning skills related to the new content [3]. Ensure that instruction (aligned with stated goals) is presented in such a way that learners understand what is expected of them (what they should be able to do and how to meet that expectation within stated timelines). Using teacher talk to clarify the thinking, reasoning and problem-solving strategies students can employ to achieve goals can help students progress through lesson activities [21]. Intensive instruction can be readily implentegrated into multi-tier systems of support such as Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS). These frameworks support learning at different levels of intensity. Response to Intervention and PBIS are frameworks used to match learner ability and behavioral needs with the appropriate amount of instruction and intervention. Both frameworks employ differentiation using varying tiers of intervention of increased intensity according to ongoing assessment data to guide the frequency and intensity of instruction and group size. Instructors use assessment data to determine whether students would benefit from only Tier 1 (core instruction), Tier 2 (additional supplemental) or Tier 3 (intensive supports) [7].

Teach Students to Maintain and Generalize Learning (HLP 21)

Generalization and maintenance of learning are key to increase academic achievement in SWD. Generalization is the ability to apply a learned skill in different settings and situations. For example, a student learns to count objects in the classroom and then is able to count pieces of candy at the store. Maintenance occurs when an individual is able to perform a skill with the same or better accuracy level across time [22]. Generalization and Maintenance must be essential components of active instruction because they increase the likelihood that students will be able to apply skills in more than one setting over extended periods of time. Effective teachers provide opportunities for maintenance and generalization so that students remember skills and apply that knowledge when learning more sophisticated skills [23]. Teachers can integrate a wide variety of EBPs into lessons to consistently review and reinforce skill acquisition [7]. Table 3 offers an overview of strategies to implement these HLPs in traditional and remote learning settings.

Actively Engage Learners

Planning with a purpose and teaching for success by providing explicit and intensive instruction which scaffolds learning so students can maintain and generalize skills over time are critical dimensions of meaningful instruction. The HLPs in this category are: (HLP 18) Use strategies to promote active engagement, (HLP 19) Use assistive and instructional technologies, and (HLP 22) Provide positive/constructive feedback to guide learning and behavior.

Use Strategies to Promote Active Student Engagement (HLP 18)

Student engagement is considered a predictor of academic achievement. Regardless of age or ability levels, actively engaged students experience greater academic and social success [23]. Active student engagement is a multi-dimensional construct encompassing behavioral (participation), emotional (affective reactions), and cognitive (levels of effort) components. The interaction of these components of engagement constitutes a dynamic process that can positively influence student learning and achievement [3,24,25]. Establishing and maintaining positive teacher-student and student-student relationships can help instructors to connect learning to student backgrounds, special interests and preferred learning modalities. Effective teachers use a variety of EBPs to motivate students to be actively engaged in daily instruction.

Use Assistive and Instructional Technologies (HLP 19)

The 1997 reauthorization of the IDEA [26] required that school district teams consider the use of assistive technology (AT) when planning the Individualized Education Program of SWD. This action ensured SWD would benefit from access to technology devices and services that increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities (excluding surgically implanted medical devices). SWD often utilize AT during instruction and assessment to acquire and demonstrate learning. Assistive technology devices can range from low technology (e.g., changes in lighting, instructional manipulatives, slant boards, pencil grips, sensory input items) to high technology devices (e.g., software programs: voice recognition, spell checking, word prediction as well as computers, tablets, phones, reading pens, digital recorders [27]. While low tech AT devices continues to be in use (augmentative and assistive communication devices), recent advances in technology in conjunction with the basic tenants of the inclusion movement has influenced a shift in focus to the use of instructional technology and universal design of learning strategies [27]. For example, students receiving instruction in general education may use learning-oriented games and software, applications and sophisticated electronic devices to support their active participation and learning [3]. The practice of using AT during regular instruction enables learners to learn to use them during assessment without difficulty which can minimize unnecessary barriers to demonstrate knowledge. Considerations which can guide choices related to planning accommodations for SWD include identifying specific tasks students may not be able to do, evaluating the effectiveness of current and previous strategies, accommodations and AT implemented, identifying barriers to success and investigating available ATs to address instruction and assessment needs [28].

Provide Positive and Constructive Feedback to Guide Learning and Behavior (HLP 22)

Effective teachers use positive and constructive feedback as a way to guide learning and behavior while also maintaining learner motivation and active engagement. Feedback is conceptualized as information provided as a consequence of a given performance. Whether written, verbal, or non-verbal, feedback exercises a powerful influence on the learner and thus, must be used positively [7]. Positive and constructive feedback must provide information specifically related to the academic or behavior performance in a way that the learner will understand. In fact, the most significant student achievement often occurs as students receive information feedback specifically in a timely manner. Learner feedback should include a clear analysis about learner performance on a task in conjunction with specific instruction and detail about how to improve performance. Feedback solely based on praise, rewards, and punishment is not as useful. Feedback must be immediate, genuine, and age appropriate in order to produce the desired effect [3, 29]. Table 4 offers an overview of strategies to implement these HLPs in traditional and remote learning settings.

Final Thoughts and Practical Implications

Helping instructors of SWD bridge the gap between research and practice through the development of foundational skills can improve the quality of teacher education and professional development programs. The current challenging circumstances related to the global pandemic, including sudden changes to remote instruction supervised by parents, call for the use of evidence-based and effective instructional practices more than ever before. The HLPs are EBPs essential in teaching and meeting the learning needs of SWD. The question becomes, “How can teachers ensure these practices are delivered as intended in traditional and remote settings?” The answer is for instructors of SWD in varied settings to learn what the HLPs entail and how to apply them across settings and content areas while being aware of barriers to communication that can impede effective instructional delivery. Ensuring the HLPs are applied with fidelity based on achievement data, self-reflection, as well as positive, corrective feedback is essential [3]. As described, the HLPs can become an integral part of a teacher’s practice. The HLPs must be considered in the planning process before implementation. Instructors who are mindful and confident about how to use the HLPs in conjunction with content expertise can readily apply them as they identify, develop and prioritize long and shortterm goals, and systematically design instruction [17]. However, as teaching for success and positive outcomes are the ultimate goals, communication is key when teaching in traditional and remote settings. When planning, instructors of SWD must prepare for students who have communication difficulties (i.e., speech, language and/or hearing impairments) as well as modes of delivery that require remote learning or the use of protective facial gear. These teaching conditions may alter speech volume and nonverbal communication, such as facial expressions and gestures, impeding the effective delivery of services [30], Teaching practices that require student engagement [23], explicit teaching with scaffolded support [16] must be delivered effectively in order for generalization and maintenance to occur [3,4]. Selecting appropriate AT devices aid in both planning and implementation to determine the best mode of communication. Weighing these factors for the best outcomes for SWD is essential.

References

- Hurwitz S, Perry B, Cohen ED, Skiba R (2020) Special education and individualized academic growth: A longitudinal assessment of outcomes for students with disabilities. American Educational Research Journal 57(2): 576-611.

- Cook BG, Haggerty NK, Smith GJ (2018) Leadership and instruction: Evidence-based practices in special education. In Handbook of Leadership and Administration for Special Education (pp. 353-370). Routledge.

- McLeskey J, Maheady L, Billingsley B, Brownell M, LewisT (2018) High-leverage practices in special education. Routledge.

- Maheady L, Rafferty LA, Patti AL, Budin SE (2016) Leveraging change: influencing the implementation of evidence-based practice to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. Learning Disabilities-A Contemporary Journal 14(2): 109-120.

- Council for Exceptional Children (2020) Key Considerations for Special Educators and the Infants, Children, and Youth They Serve as Schools Reopen.

- S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs (2020). 41st Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2019, Washington, USA.

- Billingsley B, McLeskey J, Crockett J (2018) Providing Support for All Students. Handbook of Response to Intervention and Multi-Tiered Systems of Support. Routledge.

- Lowrey KA, Classen A, Sylvest A (2019) Exploring ways to support preservice teachers' Use of UDL in planning and instruction. Journal of Educational Research & Practice 9(1): 26-32.

- Giamellaro M, Lan MC, Ruiz-Primo MA, Li M, Tasker T (2017) Curriculum Mapping as a strategy for supporting teachers in the articulation of learning goals. Journal of Science Teacher Education 28(4): 347-366.

- Andersson C, Palm T (2017) The impact of formative assessment on student achievement: a study of the effects of changes to classroom practice after a comprehensive professional development program. Learning and Instruction 49: 92-102.

- Rao K, Meo G (2016) Using universal design for learning to design standards-based lessons. SAGE Open 6(4): 1-12.

- Webb S, Massey D, Goggans M, Flajole K (2019) Thirty‐five years of the gradual release of responsibility: scaffolding toward complex and responsive teaching. The Reading Teacher 73(1): 75-83.

- Park V, Datnow A (2017) Ability grouping and differentiated instruction in an era of data-driven decision making. American Journal of Education 123(2): 281-306.

- Kurth J A, Ruppar A L, McQueston J A, McCabe KM, Johnston R, Toews SG (2019) Types of supplementary aids and services for students with significant support needs. The Journal of Special Education 52(4): 208-218.

- Joyce J, Harrison JR, Gitomer DH (2018) Modifications and accommodations: a preliminary investigation into changes in classroom artifact quality. International Journal of Inclusive Education 24(2): 181-201.

- Lemons CJ, Vaughn S, Wexler J, Kearns DM, Sinclair AC (2018) Envisioning an improved continuum of special education services for students with learning disabilities: Considering intervention intensity. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice 33(3): 131-143.

- Kruit PM, Oostdam RJ, Van den Berg E, Schuitema JA (2018) Effects of explicit instruction on the acquisition of students’ science inquiry skills in grades 5 and 6 of primary education. International Journal of Science Education 40(4) 421-441.

- Zohar A, Lustov E (2018) Challenges in addressing metacognition in professional development programs in the context of instruction of higher-order thinking. Contemporary Pedagogies in Teacher Education and Development 87.

- Pyle D, Pyle N, Lignugaris/Kraft B, Duran L, Akers J (2017) Academic effects of peer-mediated interventions with English language learners: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research 87(1): 103-133.

- Harbour KE, Evanovich LL, Sweigart CA, Hughes LE (2015) A brief review of effective teaching practices that maximize student engagement. Preventing School Failure 59(1): 5-13.

- Friesen D, Haigh CA (2018) How and why strategy instruction can improve second language reading comprehension: A review. Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal 18(1): 1-18.

- Alberto PA, Troutman AC (2019) Applied Behavior Analysis for Teachers (9th Edition). Pearson

- Barkley EF, Major CH (2020) Student engagement techniques: A handbook for college faculty. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fredricks JA, McColskey W (2012) The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 763-782). Springer.

- Wang MT, Kiuru N, Degol JL, Salmela-Aro K (2018) Friends, academic achievement, and school engagement during adolescence: A social network approach to peer influence and selection effects. Learning and Instruction 58: 148-160.

- Hoye SR (2017) Teachers' perceptions of the use of technology in the classroom and the effect of technology on student achievement. Mississippi College.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Amendments of 1997, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (26).

- OCALI (2013) Assistive Technology Resource Guide.

- Whitney T, Ackerman KB (2020) Acknowledging student behavior: A review of methods promoting positive and constructive feedback. Beyond Behavior 29(2): 86-94.

- Baltimore WJ, Atcherson SR (2020) Helping our clients parse speech through masks during COVID-19. The ASHA Leader 25(5): 34-35.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 1401(1).