Universal Design for Learning and Intellectual Disabilities

Frolli A1*, Sara Rizzo1, Valenzano L2, Lombardi A2, Cavallaro A2 and Ricci MC2

1University of International Studies of Rome, Italy

2 FINDS - Italian Neuroscience and Developmental Disorders Foundation, Caserta, Italy

Submission:June 15, 2020; Published:July 20, 2020

*Corresponding author:Frolli Alessandro, Disability Research Centre of University of International Studies of Rome Via Cristoforo Colombo, Rome, Italy

How to cite this article:Frolli A, Valenzano L, Lombardi A, Cavallaro A, Ricci M. Universal Design for Learning and Intellectual Disabilities. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil, 2020; 6(5): 555696. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2020.06.555696

Abstract

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an approach to educational design that promotes the idea of producing physical environments and tools in the school system in order to improve the experience of each and every student. This idea is developed through a neuropsychological model that has valuable implications in teaching practice. In fact, the identification of the three brain networks and the recognition of the uniqueness of the subjective functioning constitute the foundation of the principles and guidelines of UDL, for the creation of flexible, egalitarian and accessible to all curricula. This work aims to support the applicability of the UDL model, with its neuropsychological framework, to students with Intellectual Disabilities (ID). The integration between the UDL framework and teaching strategies, such as, functional behavior analysis, teacher made interventions, class wide peer tutoring and curriculum modifications, can promote universal design for learning and inclusive teaching for all students, even with different level of ID.

Keywords: Universal Design for Learning; Intellectual Disability; Teaching Strategies; Teachers

Abbreviations: UDL: Universal Design for Learning; UD: Universal Design; SEN: Special Educational Need ; CAST: Centre for Special Applied Technologies; ID: Intellectual Disability

Introduction

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an approach to educational design that is based on the assumption that diversity is a constant in all contexts and in all individuals, which is why the interventions must be planned through a flexible teaching proposal and characterized by plurality since their design. UDL originates from the field of architecture, within which the Universal Design (UD) was born with the aim of leading to the universalization of accessibility. This goal can be achieved through the design of spaces and environments that consider the diversity of the population who will benefit from it, rather than contrasting the inaccessibility experienced by individuals, with and without disabilities, through subsequent readjustment of the structures. The Universal Design (UD), was originated by Ronald L. Mace (1941-1998), which is traditionally considered the father of the movement, as well as the 7 principles that characterize the UD. The Center for Universal Design was founded by Mace in 1989, at the North Carolina State University

The 7 principles of UD arised with the participation of a team of architects, designers, engineers and researchers in the field of environmental design. At first, the attention of UD researchers focused on the creation of assisted technology, compensatory tools and software that would allow pupils with disabilities, to face compensate, and overcome the difficulties experienced [1]. At the end of the 1980s, grew the awareness on how focusing on assisted technologies would have shadowed the leading role played by the school environment in facilitating, or hindering, the students learning process with respect to the approach in the conceptualization of the didactic proposal. The reflection on the difficulties that the individual with disabilities and/ or with Special Educational Need (SEN) can find in the educational environment, has primarily pushed the UDL towards the limitations acceptance and the obstacles reduction posed by the condition of disability, and also towards the identifying and lifting the barriers imposed by the educational environment. In the early 1990s, the Centre for Special Applied Technologies (CAST) considered that the concept of universal design contained within itself those useful aspects to face the challenge for creating an education for everybody, through concrete application of criteria capable of directing teacher’s practices towards a global transformation of training systems [2]. UDL and UD have in common the idea of producing physical environments and tools in the school system in order to improve the experience of each and every student. The application of the concept of accessibility for learning environments, is a much more complex process since teaching and learning are structured as different activities and more delicate than design and construction of new spaces. The point is not only to ensure the reception of all students in the school environment, but also to promote accessibility in the learning spaces that are proposed by the institution, taking into account the complexity of cognitive processes, affective, and relational involved in relation to the limitations of the curriculum proposal.

Discussion

UDL proposes a functional and organized model of the brain where three main interconnected neural networks would be identifiable. In the back of the brain is placed the recognition network (the “what” of learning), which presides the reception and the first processing of the information received through the senses. This network, therefore, recognize the elements that reach perception and makes them available to the memory and to the other two main networks. According to Rose and Meyer, this network is activated every time we are in a receptive mode to the world around us, unconsciously. The second network, defined as strategic (the “how” of learning), is located in the frontal part of the brain and processes the information received from the recognition network. This network allows us to give answers to complex problems through reasoning. While the recognition network determines the way in which information is received from outside, the strategic network deals with how such information is reintroduced into the environment by the individual that selects and organizes it. The last one is the affective network (the “why” of learning), responsible for reporting the information processed by the other two networks, setting priorities based on interests, thoughts present in memory, emotions. This network can function as a brake, if a certain content evokes negative memories, or if it arouses negative emotions such as anxiety, compared to, for example, a specific situation. The positively stimulated affective network can also function as a motivator. The modes of functioning and interaction of networks have an interindividual variability, which also generates the variability of learning between subjects. Furthermore, where a health condition or environmental element hinders the functioning of one of these networks, the differences between individuals will be more prominent (Figure 1). Brain diversity, as well as the variability and uniqueness of each person’s learning processes, have been recognized by research, and are therefore essential elements in the educational context for any type of student. Thus, the identification of the three brain networks and the recognition of the uniqueness of the subjective functioning constitute the foundation of the principles and guidelines of UDL, for the creation of flexible, egalitarian and accessible to all curricula.

The UDL’s three main assumptions consist of

Providing multiple means of representation (the “what” of learning), in order to offer students different possibilities of acquiring information and knowledge. This principle identifies the students’ ability to understand and learn the information they receive, the differences that depend on the methods and materials that the teacher uses (2). Thus, the teacher will have to offer students multiple ways to acquire content and develop knowledge, including a variety of methods and materials to diversify the presentation of content. Providing students with multiple means of representation can sustain learning processes and, moreover, provides learners with numerous ways to acquire information based on their individual learning style, experiences and background knowledge.

Providing multiple means of action and expression (the “how” of learning) in order to produce a plurality of opportunities for students to demonstrate their skills. This principle refers to the means of action and expression that students can use to demonstrate their learning. Meyer & colleagues [2] highlighted that teachers must lead students to become expert apprentices, namely, developing their executive function skills, in terms of goal setting, self-monitoring progress, adaptation of learning strategies. This can be useful to support students in expressing what they know and what they have learned, considering individual differences. Some students may feel comfortable expressing feelings in writing, but not with speech, and vice versa. Others may have difficulties in the strategies, practices and organization of the means of expression. It is therefore essential to provide options for action and expression.

Providing multiple means of engagement (the “why” of learning) to capture and broaden students’ interests and maintain high motivation for learning. The principle of multiple means of engagement require students to contribute to learning tasks that attract, stimulate, and engage them [2]. Meyer & colleagues [2] clarified that this engagement can be accomplished by addressing student interest, supporting options for sustaining effort and persistence, and assisting students learn to self-regulate. All this therefore also entails drawing on the interests of the students, overcoming the appropriate challenges and increasing motivation. Affection is a fundamental aspect of learning and individualization, as students differ substantially in their involvement and motivation to learn

Multiple elements play a significant role in the individual variability, such as neurology, culture, personal relevance, subjectivity and basic knowledge, and many others. Teachers who create multiple means of engagement support affective learning by tapping into learners’ interests and offering appropriate challenges to increase their motivation. These three principles form the basis for the new UDL Guidelines [3], have the primary objective of directing teachers to adequately address the wide range of interindividual differences they encounter within each class of students. The Guidelines contain ideas and concrete indications applicable to any discipline, so that it is possible to ensure each student equal opportunities for learning and access to training spaces that are capable to promote success.

Intelligence is the general mental capacity that involves reasoning, planning, problem solving, abstract thinking, understanding complex ideas, effective learning and learning from experience [4]. Historically, Intellectual Disability (ID) (previously defined as “mental retardation”) was defined on the basis of: a) cognitive deficits, established through a standardized measurement of intelligence, in particular with an QI score less than 70; b) significant deficits in functional and adaptive capacities, such as the ability to perform age-appropriate daily life activities. The term “mental retardation” used in previous editions of the DSM has been replaced by the diagnostic term “Intellectual Disability”, and as “Intellectual Developmental Disorder” to reflect deficits in cognitive ability from the developmental stage. DSM-5 defines IDs as neurodevelopmental disorders with early childhood onset, characterized by intellectual difficulties and difficulties in conceptual, social, and practical areas of life. According to the DSM-5, ID diagnosis is met through three criteria: 1) Deficiency in intellectual functioning - “reasoning, problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning, and learning from experience” - confirmed by clinical evaluation and individualized standard IQ testing [5]; 2) Deficit in adaptive functioning that results in failure to meet developmental & sociocultural standards for personal independence & social responsibility. Without ongoing support, the adaptive deficit limit functioning in one or more activities of daily life (e.g., communication, social participation, independent living) across multiple environments (e.g., home, school, work, community). “The deficit in adaptive functioning must be directly related to the intellectual impairments described in Criterion A” [6]. In fact, one of the fundamental problems encountered by individuals with ID is the inability to recognize and avoid both physical and social risks; 3) Onset of intellectual and adaptive deficits during developmental period. The age and characteristic features at age of onset depend on the etiology and severity of brain dysfunction. It should be noted that DSM-5 does not specify a maximum age at which the onset of impairments should occur.

The assessment of intelligence across three domains (conceptual, social, and practical) will ensure that clinicians base their diagnosis on the impact of the deficit in general mental abilities on functioning needed for everyday life. This is especially important in the development of a treatment plan. The definition of the DSM-5 reflects a more complete view of the individual than the previous edition. Indeed, DSM-IV included alterations in general mental abilities that affect the individual’s functioning in areas of conceptual, social, and daily life. The DSM-5 also abandoned specific IQ scores as a diagnostic criterion, although it retained the idea of a general functioning of one or two standard deviations below the general population. The DSM-5 mostly emphasized the area of adaptive operation and performance in life skills, as “individual cognitive profiles based on neuropsychological testing are more useful for understanding intellectual disabilities than a single IQ score” [6]. In contrast to DSM-IV, which states that impairments must be present in two or more areas of competence, the criteria of DSM-5 indicate a compromise in one or more higher skill domains (conceptual, social, practical) [7]. ID is indicated, even in earlier editions of the DSM, by the diagnostic terms “mild”, “moderate”, “severe”, and “deep” to define the severity of the condition. This terminology is useful as aspects of mild to moderate identification differ from severe to deep identification. The DSM- 5 maintains this connotation with a greater focus on daily skills rather than specific IQ intervals.

Conclusion

Through the years, the UDL proved to be a promising approach to enabling students with significant intellectual disabilities to be located in inclusive and accessible educational contexts, created through the integration of UDL and technology. With regard to severe disabilities, the UDL framework states that those students that require access to certain learning media should not be defined by their perceived impairments [7]. The UDL framework encourages teachers to broaden their expectations about educational contexts and to consider what could happen if curriculum were developed to include multiple to creatively engage students with severe disabilities in the learning process and show or act based on their knowledge [7]. Teachers may use UDL to identify roadblocks within the curriculum to design and develop flexible curricula that minimize those limitation, before assuming that students with severe disabilities cannot learn or benefit from education. In fact, UDL aims to reduce potential learning barriers, while increasing learning opportunities: the basic concept is that design for different students translates into better learning outcomes for all individuals [8]. In addition, UDL encourages the perception where students with severe disabilities are seen as valuable students who are able to develop and learn, if curricula are proactively designed to meet their individual needs [9]. The UDL framework supports teachers in a more inclusive view of the curriculum and in a greater understanding of individual variability as natural. It also provides clear ways for teachers to ensure students’ access to learning and to develop a lifelong passion for the learning activity [10]. In other words, the UDL framework helps teachers understand that one of the main aims of education is to allow all students to develop a mastery of knowledge, which occurs when students are motivated, enterprising and strategically engaged in learning [2]. The process of mastering knowledge is described as becoming an expert student. Expert Students are defined as: proactive and motivated, enterprising and competent, strategic and direct [2]. Research actively supported the integration between UDL principles to improve accessibility for students with ID [11,12]. However, some of the systematic literature reviews show a lack of studies with respect to inclusion [13] especially with regard to students with ID [14]. In particular, we recall that Rao et al, (14) propose some interesting questions to guide future research on the subject of the applicability of the UDL with students with ID. First, Rao questions how UDL can be applied to curriculum design and individualized media to support the inclusion of subjects with ID; specifically, how it can reduce barriers and strengthen the student’s strengths to promote concrete inclusion. Secondly, Kao et al, question how UDL can be used in synergy with existing evidence-based practices to support students’ academic, behavioral, and social goals with ID. Finally, they inquiry how UDL can be integrated within multi-tiered systems of support for students with ID, that is within the context of general educational initiatives in the school landscape. It is possible to partially answer to these questions considering that the effectiveness of students with intellectual disabilities, and of the class in general, can be improved if educators filter learning through didactic strategies [15]. In fact, the integration between the UDL framework and teaching strategies, such as, functional behavior analysis, teacher made interventions, class wide peer tutoring and curriculum modifications, can promote universal design for learning and inclusive teaching [15,16]. UDL, shapes a unifying model in conjunction with pedagogical approaches and technology, that includes multiple strategies aimed at fostering learning and collaboration [17]. As previously mentioned, we should not forget the role of technologies to support the inclusion and individualization of student paths with ID. McMahon et al. (18). In this regard, conducted a study on the effects of augmentative reality in UDL perspective compared to the vocabulary teaching science to students with ID. The study demonstrated the effectiveness of computer-aided instruction interventions, implemented according to the three UDL principles of providing means of action and expression, engagement, and representation. Therefore, while research on the applicability of the UDL approach to intellectual disabilities is still growing, and while there are still large areas to explore, the studies carried out so far demonstrate the effectiveness of the UDL principles and guidelines with regard to inclusion, individualization, and accessibility for students with ID within the school context.

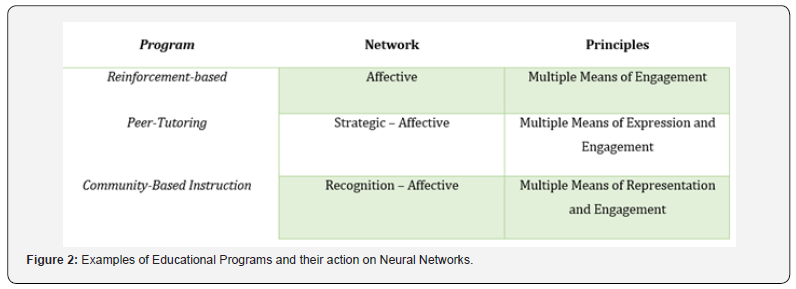

As demonstrated, the UDL is a framework that offers a solid neuropsychological basis also applicable to IDs. UDL model flexibility allows it to be implemented in conjunction and synergy with the different teaching strategies that can be hypothesized in the case of students with ID. Each of these didactic strategies reflects the work on one or more networks among those described by the UDL. For instance, a reinforcement-based program will work on the operation of the affective network, while a peer-tutoring program will work both on the strategic and affective network (Figure 2). This association involves a reflection on the practical implications for the implementation of UDL-based strategies: in the event of educational deficiency or a failed strategy it is possible to identify and strength the network (or networks) is associated with UDL-based strategies. The educational program in place, allows to work on one or more networks involved. Consequently, that deficit network can be stimulated through the appropriate multiple means so that the students with ID can achieve their educational success [19,20].

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- Mangiatordi A (2017) Didattica senza barriere, Teaching Without Barriers Universal Design, sustainable technologies and resources Edizioni ETS, Pisa, pp. 124.

- Meyer A, Rose, DH, Gordon D (2014) Universal design for learning: Theory and practice, Wakefield MA: CAST, USA.

- CAST (2011). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.0. Wakefield, MA, USA.

- AAIDD (American Association on Intellectual Developmental Disabilities) (2010) Intellectual disability: Definition, classification, and system of supports. Washington, DC: AAIDD, pp. 259.

- Papazoglou A, Jacobson LA, McCabe M, Kaufmann W, Zabel TA (2014) To ID or not to ID? Changes in classification rates of intellectual disability using DSM-5. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 52(3); 165-174.

- APA (American Psychiatric Association) (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th), Washington DC, USA.

- Hartmann E (2015) Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Learners with Severe Support Needs. International Journal of Whole Schooling 11(1); 54-67.

- Coyne P, Pisha B, Dalton B, Zeph L A, Cook Smith N (2012) Literacy by Design: A Universal Design for Learning Approach for Students With Significant Intellectual Disabilities, Remedial and Special Education 33(3); 162-172.

- Ainscow M, Howes A, Farrell P, Frankham J (2003) Making sense of the development of inclusive practices. European Journal of Special Needs Education 18(2); 227-242.

- Rose D H, Meyer A (2006) A practical reader in universal design for learning, Harvard Education Press.

- Jackson R M (2005) Curriculum access for students with low incidence disabilities: The promise of universal design for learning. Wakefield, MA: Center for Applied Special Technology.

- Wehmeyer M L (2006) Beyond access: Ensuring progress in the general education curriculum. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 31(4); 322-326.

- Oliveira de Pavia A R, Van Munster M D A, Goncalves A G (2019) Universal Design for Learning and Inclusive Education: a Systematic Review in the International Literature, Rev Bras Ed Esp, Bauru, 25(4); 627-640.

- Rao K, Smith SJ, Lowrey K A (2017) UDL and Intellectual Disability: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go?, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 55(1); 37-47.

- Jimenez T C, Graf V L, Rose E (2007) Gaining access to general education: The promise of universal design for learning. Issues in Teacher Education 16(2); 41-54.

- Al-Azawei A, Serenelli F, Lundqvist K (2016) Universal Design for Learning (UDL): A Content Analysis of Peer Reviewed Journals from 2012 to 2015. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 16(3): 39-56.

- Howard, Kirsten L (2004) Universal Design for Learning: Meeting the Needs of All Students. In the Curriculum-Multidisciplinary. Learning & Leading with Technology 31(5): 26-29.

- McMahon D D, Cihak DF, Wright R E, Bell S M (2016) Augmented Reality for Teaching Science Vocabulary to Postsecondary Education Students With Intellectual Disabilities and Autism, Journal of Research on Technology in Education 48(1): 38-56.

- Al Hazmi A N, Ahmad A C (2018) Universal Design for Learning to Support Access to the General Education Curriculum for Students with Intellectual Disabilities, World Journal of Education 8(2): 66-72.

- CAST (2008) Universal design for learning guidelines version 1.0. Wakefield, MA: Center for Applied Special Technology. USA.