Applying the Yerkes-Dodson Law to Understanding Positive or Negative Emotions

Patrick G Gwyer*

Clinical Psychologist, England, UK

Submission: September 11, 2017; Published: September 27, 2017

*Corresponding author: Patrick G Gwyer, Clin Psych Associate Fellow of the British Psychological Society, Chartered Psychologist, Clinical Psychologist, Chartered Scientist, England, Email: pat@carpevitatherapies.com

How to cite this article: Patrick G G. Applying the Yerkes-Dodson Law to Understanding Positive or Negative Emotions. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017; 3(2): 555606. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2017.03.555606

Short Communication

Emotions have sometimes been defined and referred to as either positive or negative, with the use and generation of positive emotions seen as an essential component of our wellbeing and happiness [1-5].

However, this might not be a very helpful approach to take. Rather than emotions being labeled as “positive” or “negative” a more helpful and mindful approach would be to simply acknowledge and accept they are as they are-a response and expression of how we are feeling [6-8].

This approach requires us to pay more attention to our emotions. We can do this through the wide-angle lens of expansive, the zoom-lens of constrictive, or the bare attention of mindful refection [9-11]. By doing this we have the choice to let go of, or reflect (which could include savoring and gratitude) the emotion, but still acknowledge and accept they “are as they are”, but with greater reflection and understanding of the context in which they occur.

The non-compartmentalizing of experience (and by extension emotions), is key to our ability to accept, assimilate and accommodate, and find meaning in all of our human experiences, without artificially attempting to experience (e.g., positive) or avoid (e.g., negative) certain aspects of life such as emotions.

This has long been postulated as a key component of psychological growth and wellbeing in clinical practice [12-24].

Instead of focusing upon the emotion and labeling it as positive or negative, what might be more helpful – once it has been acknowledged - might be to consider the Intensity at which the emotion is experienced. The rationale for this is provided by the Yerkes–Dodson law [25] shown in Figure 1 below.

The Yerkes Dodson law is represented by an inverted U shape and states that our performance on any task including our ability to manage our wellbeing and happiness and regulate our emotions - is related to the intensity of what we are experiencing (e.g., physiological, emotional or psychological arousal). Evidence shows that when levels of intensity are too low or too high, our performance is impaired [26].

We can use the example of FEAR to illustrate how this applies to our emotions. Ask yourself “Is fear a ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ emotion?” The answer is of course neither, it can be both. We can show that in the following example.

If we never felt any fear and did dangerous and silly things as a result, it would be quite unhelpful. Alternatively, if we felt so much fear that we never left the house by ourselves because we were too frightened, again it would be quite unhelpful. However, what if we felt just enough fear to stop us walking down a dark alleyway at night, this would be helpful.

It is possible to do this with all emotions and so we can see, it is not the emotion that is “positive” or “negative” but how intensely the emotion is felt and if the intensity is appropriate and proportionate to what is happening (i.e., the context of the emotion) and if this is helpful. What is of course essential is getting the balance right to the situation. This can only be achieved by taking into account the context in which the emotion is felt and how it is expressed [27].

Additionally, by using the terms helpful and unhelpful, instead of positive or negative, we are reframing our experiences in a less pejorative, more functional, constructive and selfcompassionate way [28].

Within our nervous system we have two systems linked to our Limbic system (the sympathetic and the parasympathetic), that work in harmony to maintain homeostasis and create balance to ensure our survival and optimal functioning [29].

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) controls our response to danger and threat (fight-flight-freeze-appease) and when activated, we may notice that our breathing becomes quicker, our heart beats faster and we get knots in our stomach as our bodies prepare for action. Fortunately, we have the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) to balance the SNS and soothe and relax us [30-31].

It is suggested therefore that intensity is a better “operational definition” than positive or negative (if one indeed needs to be applied), as it can be linked to our limbic system’s activation (i.e., low intensity = low activation / high intensity = greater activation) and the role of the SNS and PSNS in ensuring balance and an optimal level of intensity/arousal [32]. This theoretical underpinning cannot be so easily achieved with the definition of positive and negative.

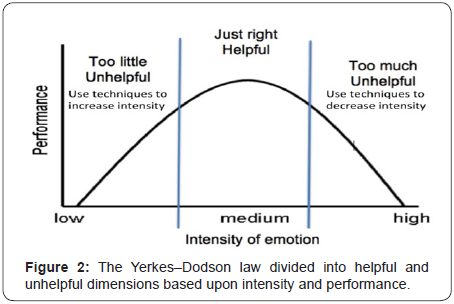

By linking to levels of nervous system arousal, this also gives us a framework in which we can either increase or decrease the unhelpful levels of arousal through therapeutic interventions (e.g., mindfulness, breathing techniques, physical exercise, relaxation techniques, distress tolerance). This is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Finally, to label and compartmentalize an emotion as positive or negative, without considering its Function, as defined by what it is pushing us away from, or pulling us towards [7,33,34] also ignores the evolutionary advance of emotions [35-38]. Evolution does not define things in terms of positive or negative, only in terms of what is helpful and unhelpful, or functional and adaptive to our survival [39-40].

Conclusion

In this speculative brief paper, it is suggested that what is important to think about when we consider emotions, is not if they are positive or negative, but instead their Intensity and Function. From this an individual can reflect if their expression of that emotion is helpful or unhelpful (i.e., appropriate and proportionate to what is happening around them [or what has occurred], if acting [or not acting upon them] is safe to others or themselves and in line with their goals). The use of positive and negative does not offer this richness and ability for reflection and growth. Many therapeutic approaches (e.g., CAT, Schema, Gestalt, DBT, ACT and CBT to name but a few) offer a number of strategies by which this can be achieved without the artificial dichotomizing into positive and negative and emphasize the importance of considering the whole person and integration of all experiences into that whole [41]. Indeed, this capability is part of an individual’s ability to self-regulate their emotions and requires an understanding of the context in which they occur, something that is lost by a simple definition of positive or negative which directs the attention towards the emotion, and away from the context in which it is occurring.

References

- Fredrickson BL (1998) What good are positive emotions? Rev Gen Psychol 2(3): 300-319.

- Fredrickson BL (2016) Leading with positive emotions.

- Fredrickson BL, Joiner T (2002) Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psycho sci 13(2): 172-175.

- Meneghel I, Salanova M, Martinez IM (2016) Feeling good makes us stronger: How team resilience mediates the effect of positive emotions on team performance. Journal of Happiness Studies 17(1): 239-255.

- Gloria CT, Steinhardt MA (2016) Relationships among positive emotions, coping, resilience and mental health.Stress and Health 32(2): 145-156.

- Oatley K (1988) Plans and the communicative function of emotions: A cognitive theory. In Cognitive perspectives on emotion and motivation. Springer Netherlands 345-364.

- Linehan M (1993) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford press.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD and Wilson KG (1999) Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press.

- LaBerge D (1995) Attentional processing: The brain’s art of mindfulness. Harvard University Press 2.

- Shapiro DH (1982) Overview: Clinical and physiological comparison of meditation with other self-control strategies. Am J Psychiatry 139(3): 267-274.

- Valentine ER andSweet PL (1999) Meditation and attention: A comparison of the effects of concentrative and mindfulness meditation on sustained attention. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 2(1): 59-70.

- Brazier D (1996) Zen Therapy: Transcending the Sorrows of the Human Mind. John Wiley and Sons, NY, USA.

- Clarkson P and Cavicchia S (2013) Gestalt counselling in action. Sage. Chicago, USA.

- Ellis A (1962) Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. University of Michigan Press, USA.

- Frankl V (1946/Vienna, Austria. 1959 United States). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press, USA.

- Kelly G (1955) The psychology of personal constructs. New York, USA, 1 & 2.

- Maslow AH (1964) Religions, values, and peak-experiences. Columbus, Ohio State University Press, USA, pp. 35.

- Maslow AH, Frager R and Cox R (1970) Motivation and personality. J Fadiman and C McReynolds (Eds.), New York, USA, 2: 1887-1904.

- Rogers C (1961) A therapist’s view of psychotherapy: on becoming a person. London, UK.

- Rogers C (1980) A way of being. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, USA.

- Rogers C (2012) On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, USA.

- Perls F, Hefferline R and Goodman P (1951) Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality. Julian Press, Germany.

- Philippson P (2012) Gestalt therapy: Roots and branches-collected papers. Karnac Books, UK.

- du Plock S (2009) Handbook for Theory, Research, and Practice in Gestalt Therapy.Existential Analysis 20(2): 372-376.

- Yerkes RM, Dodson JD (1908) The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit‐formation. Journal of comparative neurology 18(5): 459-482.

- Cohen RA (2011) Yerkes–Dodson Law. In Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology, Springer New York, USA, pp. 2737-2738.

- Cohen RA (2011) Yerkes–Dodson Law. In Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology, Springer New York, USA, pp. 2737-2738.

- Becker CB, Zayfert C (2001) Integrating DBT-based techniques and concepts to facilitate exposure treatment for PTSD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 8(2): 107-122.

- Carlson NR (2012) Physiology of behavior. Prentice Hall.

- Bracha H S (2004) Freeze, flight, fight, fright, faint: Adaptationist perspectives on the acute stress response spectrum. CNS spectrums 9(9): 679-685.

- Jansen AS,VanNguyen X,Karpitskiy V, Mettenleiter TC, Loewy AD, et al. (1995) Central command neurons of the sympathetic nervous system: basis of the fight-or-flight response. Science 270(5236): 644- 646.

- Diamond DM, Campbell AM, Park CR, Halonen J, Zoladz PR, et al. (2007) The temporal dynamics model of emotional memory processing: a synthesis on the neurobiological basis of stress-induced amnesia, flashbulb and traumatic memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson law. Neural plasticity.

- Youngstrom E and Izard CE (2008) Function of emotions functions of emotions and emotion - related dysfunction. Hand book of approach and avoidance motivation.

- Parrott WG (1999) Function of emotion: Introduction. Cognition & Emotion 13(5): 465-466.

- Nesse RM (1990) Evolutionary explanations of emotions. Hum Nat 1(3): 261-289.

- Scott JP (1980) The function of emotions in behavioral systems: A systems theory analysis. Emotion: Theory, research, and experience 1: 35-56.

- Scott J(2013) The function of emotions. Theories of Emotion 1: 35.

- Kenrick DT, Sadalla EK, Keefe RC (1998) Evolutionary Cognitive Psychology: The Missing Heart of Modern. Handbook of evolutionary psychology: Ideas, issues, and applications 485.

- Cosmides L, Tooby J (2000) Evolutionary psychology and the emotions. Handbook of emotions 2: 91-115.

- Buss DM (2005) The handbook of evolutionary psychology. In: Buss DM (Ed.), John Wiley & Sons.

- Gwyer P (2016) An exploration into Positive Psychology and Clinical Psychology. Unpublished MSc Dissertation. University of EastLondon, UK.