Nurse's Stigmatising Attitudes towards Persons with a Mental Disorder; A Potential Barrier For Integration of Mental Health Services Within Urban Health Centres in a Selected District Hospital In Rwanda

Vedaste Baziga*

College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda, Rwanda

Submission: July 05, 2017; Published: July 28, 2017

*Corresponding author: Vedaste Baziga, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda, Tel: +250784499986; Email: vedastebazigal@yahoo.fr

How to cite this article: Vedaste B.Nurse's Stigmatising Attitudes towards Persons with a Mental Disorder; A Potential Barrier For Integration of Mental Health Services Within Urban Health Centres in a Selected District Hospital In Rwanda. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017; 2(2): 555585. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2017.02.555585

Abstract

Mental disorder (MD) is significantly contributing to global burden of disease and this is the fourth leading cause of global disability. To overcome this concern, the World Health Organization recommended integration for mental health care into general health care facilities and nurses have an important role in the implementation of WHO recommendation about the integration. The objectives of this study are as follows: To describe stereotypical attitudes amongst urban nurses regarding persons with a mental disorder and to explore relationships between specific socio-demographic factors (age, gender, qualification, years of nursing experience and familiarity) and nurses' stigmatizing attitudes towards persons with a mental disorder in urban health centers of a selected district hospital in Rwanda.

A quantitative, descriptive cross sectional study was conducted among nurses working in urban health centres of a selected District hospital in Rwanda and a self-report questionnaire which included four demographic variables and two sections such as level of contact and the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness-Swedish version. The self-report questionnaire was distributed to the available nurses (n=128) and the next step was data analysis where SPSS version 20 was used. This study revealed that participants held negative stereotypes towards persons with MD. Association test revealed less negatives stereotypes towards MD among higher qualified nurses than lower qualified nurses, younger nursesthan older nurses and less experienced nurses than higher experienced nurses. Also, correlation test revealed that increases in LOC correlates with decrease in score in open minded & pro integration, fear and avoidance and community and mental health ideology subscales and the total score.

Keywords: Nurse; Mental disorder; Urban health centres; Stigmatizing attitude; Familiarity

Abbreviations: MD: Mental Disorder; CAMI: Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness; LOC: Level of Contact Scale; HC: Health Centres

Introduction

Mental disorder is defined as a clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome, or pattern, that occurs in an individual and is associated with distress or disability or with an increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an important loss of freedom [1] and mental disorders represent 13% of the global burden of disease and have a global prevalence ranging between 4% and 26% [2]. However, the estimate increases to 23% in high income countries [3,4]. Also it is argued that mental disorders are among the four leading causes of disability globally (OMS, 2011). Mental health problems are reported to be one of the most common causes of disability and premature death, with more than 30% of disability cases reported being related to mental disorders. Disability as a result of mental disorders is defined as any restriction or lack of ability to perform a role in the manner considered normal for a human being [5].

In 2013, the World Health Organisation recommended the integration of mental health care into general health care facilities to reduce mental health related problems considered as global and local burden. This integration is crucial in Rwandan context as long as Rwandan citizens faced a tragedy of Genocide against Tutsis in 1994 that had a significant impact on the mental health of the population, thus psychological trauma that making a burden on Rwandan mental health services [6]. To face genocide related mental health problems, the Rwandan Ministry of Health began integration of mental health into district hospitals settings. For its implementation, the integration would rely heavily on nurses who are more closed to clients 24/24hrs [7,8]. Rwanda is facing shortage of Mental Health nurses who are working in mental health sector are estimated at 0.8 per 100000 population thus the integration is really done by general nurses in both rural and urban health facility settings estimated at 5.8/100000 [9].

Current both international and local literature suggest that the integration of mental health care services into general healthcare settings including PHC will reduce stigmatizing attitudes towards mental disorders. However, it has been shown that health care professionals including nurses have negative stereotypes towards persons with a mental disorder [7,10].

To overcome this issue of stigma, anti-stigma initaives are suggested to positively impact on these negative steretypes generally include education, information sharing about mental disorders , and, familiarity by increasing contact [11-14]. Despite Rwandan integration of mental health services beginning in 2005, there are few local research regarding the mental disorder stigma among nurses who are suggested to be actively involved in the implementation of integrated care [9,15,16]. This issue of stigma is a potential barrier of such integration of mental health services at the different levels within the main health care services.

The purpose of this study is to describe stigmatising attitudes towards a person with MD amongst nurses working in urban catchment area of a selected District in Rwanda to inform anti stigma initiatives to reduce stigma in health care professionals.

Material and Methods

The purpose of this study is to identify and describe stigmatising attitudes held by nurses, in Urban Health Centres within the catchment of a selected District Hospital in Rwanda, towards persons with mental disorders and to analyse the potential mediating effects of socio-demographic factors on these stigmatising attitudes; in order to inform the development of stigma reduction initiatives aimed at improving mental health care services and outcomes.

The research objectives are twofold as follows; to describe stereotypical attitudes amongst nurses regarding persons with a mental disorder and to explore relationship between specific socio-demographic factors (age, gender, qualification, years of nursing experience, and familiarity) and nurses stigmatizing attitudes towards persons with a mental disorder in a selected the District Hospital in Rwanda.

Design and instruments

This study adopted a quantitative, non-experimental, descriptive cross sectional design where a self-report questionnaire was used to facilitate an audit of the attitudes of nurses towards persons with a mental disorder.

The self-report questionnaire was divided into three sections and contained two data collection instruments. The first section concerned demographic data (Age, gender, experience and qualification). The second section contained the level of contact scale (LOC) designed by Corrigan and colleagues [17] which aimed at measuring the extent of participants familiarity with persons with a mental disorder. The third section contained the Swedish version of the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness (CAMI) instrument [18]. The original CAMI and LOC have been used extensively since and has shown high validity and reliability [19-21]. The self-report questionnaire was translated into French due to the fact that historically the teaching medium in high learning institutions was shifting from French to English.

The reliability of LOC has been reported by Holmes and colleagues (1999) to have inter-rater reliability of 0.83. Informed implied consent was also used. The rationale for the use of informed implied consent was to reduce participants' perceived risk to anonymity and confidentiality, and to attempt to reduce social desirability bias influencing participants' responses. This issue of discrimination is specifically sensitive in Rwanda due to the tragedy of genocide resulting from discrimination from one group to another is a source of national shame.Rwandan population is sensitive to their behaviour, both verbal and nonverbal, being deemed discriminatory.

Research setting and participants

The research setting was Urban Health Centers of a selected District Hospital in Rwanda. It is District Hospital is a referral hospital for 16 Health Centres within the respective District. In Rwandan health care system, the Health Centres are the first point of contact for and MHCUs. Health Centres provide essential and basic mental health care including counselling and basic medication (chlorpromazine, diazepam ) according to the essential drugs outlined in the WHO (2010).

Current statistics show that this District Hospital is serving a total population of 600.051 spread over a 1000 km square geographical area. These Health Centres do not have specialists staff in any domain; even general medical doctors who are only supervising the HC from the District Hospital and no medical technicians. However, the most staff of HC are composed of nurses including general nurses, midwifes, the Director of the HC and any other support staff. There are no mental health nurses and nursing staff in these urban HC makes a total of 136 nurses. This population was not sampled to have data statistical significance thus all of them was suggested to participate in the study. However, 128 of them participated in the current study (94.1%). The HC provide comprehensive and primary health care/services including consultation, maternity, antenatal care, hospitalization, immunization, VCT/PMTCT, etc. In addition, mental health services are integrated into health care provided at HC level.

The nurse training in Rwanda encompasses equivalents of internationally recognised courses such as the Registered nurse (A1), the Enrolled nurse (A2) and the Auxiliary nurse (A3). The auxiliary nurse (A3) is a legacy category of nurse, the course no longer offered.

Data collection procedures

Data collection followed ethical approval that has been granted by high educational institution: University of Rwanda, the CMHS Institutional Review Board on behalf of the National Ethical Committee (NEC) (CMHS/IRB/259/2015). In addition District Hospital management permission was obtained and a meeting followed and was held with Directors of Urban Health centresto discuss about modalities of data collection and a data collection schedule was agreed upon considering the working hours. As long as some nurses were on night duty, the researcher came next days to make sure that all nurses at urban health centre is approached.

The researcher collected data from all participants and Information sheets were distributed to all nurse by the researcher and time to ask questions was given immediately prior to participation. After being submitted, self-directed questionnaires were kept in the sealed box provided.

Data analysis

A codebook data was entered into the statistical computer package SPSS, Version 20. The single highest score from the LOC was recorded. Reverse scoring was applied to items 4,5,6,10,11,12,13,17 and 20 for the CAMI-S. Descriptive statistics computed included; measures of central tendency and distribution Scores were tabulated for all scales and subscales. The researcher decided to use non-parametric tests for further analysis due to the fact that the distribution of data was abnormal.

Associations were computed using the Mann whitney U test to compute associations of subscale scores and total score with demographic variables (gender) and the Kryskal Wallis H Test (associations of subscale scores and total score with demographic variables (Age, experience, category of nurse and qualification ). The Spearman's rho correlation coefficient test was used to compute correlations between scores achieved on the LOC, level of familiarity and scores achieved in the CAMI-S [22].

Ethical considerations

In the current study, implied consent was used and the researcher wants to assure participants of anonymity and attempt to reduce responses that may represent social desirability bias in an attempt to reduce social desirability bias by increasing participant's sense of anonymity [2 3]. In addition, regarding potential risks and risk minimization, the student nurses are not considered vulnerable in the same way as MHCUs. The study was argued to be low risk research. Regarding dissemination, the research setting was given a report and the researcher is in the process of publication.

Results and Discussion

Description of participants

The total number of participants was (n=126) and the majority included female participants (70.3%) and minority of male participants (29.7%). This is not surprising as nursing has historically been considered a female profession and Rwanda is not an exception to the stereotype [24].

Distribution of participants according to their age, was as follows; age 21-30 (41.4%), 31-40 (41.4%), 41-50: (10.9%) and < 51: (6.3%). Regarding the category of nurses, the majority was nurses with Diploma (89.6%) while nurses with advanced diploma were (26.6%), Bachelor's Degree (3.9%) and none among nurses was Masters' Degree holder (0, 0%)

This due to the fact that training of Advanced Diploma and above started only from 1998. The respondents were categorised into two as follows: Registered nurses (30.0%) and enrolled nurses (69.5%). Lastly, the majority of participants was experienced between 0-8 years (55.5%); followed by 9-16 (28.9%); 17-24 (9.4%) and <50 (6.3%). The response rate achieved is 94.1%.

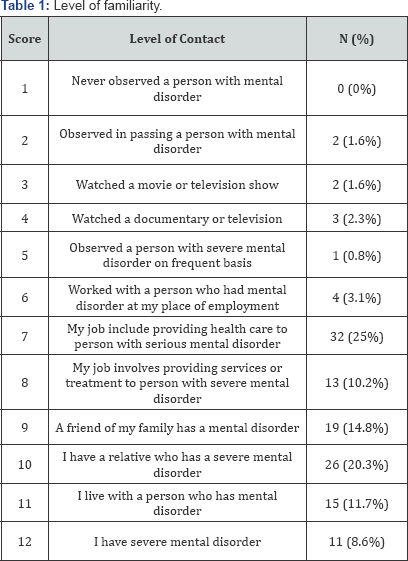

Level of contact

As displayed in Table 1, participants' level of contact, measured by the LOC scale, ranged between a score of 2 Observed a person with mental disorder in passing (1.6%, n=2) and a score of 12, I have a severe mental disorder (8.6%, n=11). Here, it is indicating that some of participants are suffering from mental disorder (s). The most commonly occurring score was level 7,providing services to person with severe mental disorder (25%, n=32).It is not surprising as long as mental health services are integrated into general health care facilities from community level to referral health care facilities thus nurses as exposed to provide health care services to different clients including clients who are suffering from mental disorders [6].

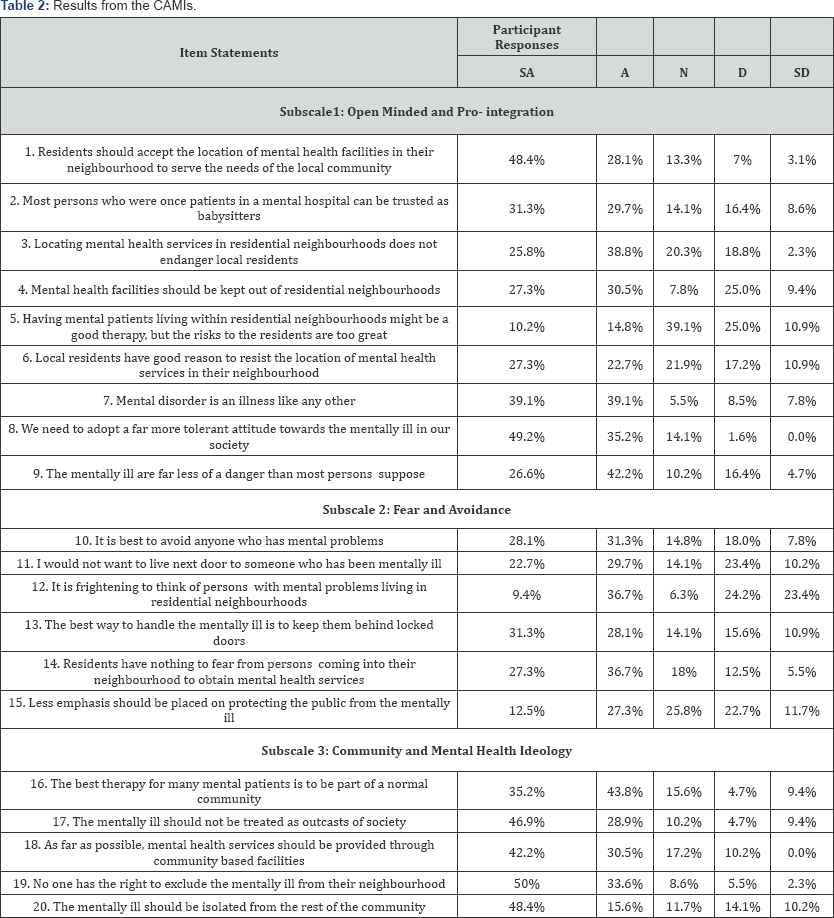

Results from the CAMIs

As displayed in Table 2, the findings from this study confirm that the participants reflected negative stereotypes towards persons with mental disorder regarding all items on CAMIs, subscales and the total score. However, the table below and measures of central tendency indicate that these negatives stereotypes were less prevalent on the following Items than others: Item4: Mental health facilities should be kept out of residential neighborhoods (44.4%) Item 5: Having mental patients living within residential neighborhoods might be a good therapy, but the risks to the residents are too great (45.9%); item 6: Local residents have good reason to resist the location of mental health services in their neighborhood and item 12: It is frightening to think of persons with mental problems living in residential neighborhoods (47.6%). Also findings from this study shown that negatives stereotypes were more prevalent on the item 19: We need to adopt a far more tolerant attitude towards the mentally ill than remaining others (1.6%). Findings from the current study are in line with international and local studies conducted previously on health care providers [1416,21]. However, Nordt et al. [25] suggest that psychiatrists and/or other health professionals generally have more positive attitudes towards mentally ill people than the general public.

These findings suggest clear contradictions amongst participants regarding different items. For example participants resist to the integration of mental health services in their community and their neighbourhoods but at the same time participants agree with the idea of tolerating and not excluding persons mentally ill. Also, the current study revealed more neutral responses than positive stereotypes in some of the items. For example while 2 5% agree; 39.1% reflected neutral responses about the idea of Having mental patients living within residential neighborhoods might be a good therapy, but the risks to the residents are too great. This is almost similar on item 15: Less emphasis should be placed on protecting the public from the mentally illwhere 39.8% agree against 25.8% reflecting neutral responses. These findings are in line with studies conducted by Griffiths et al. [26] and Putman [27] suggesting that contradictions and neutral positions might be the result of social desirability bias. It is possible that the extent of neutral responses within this study is also a reflection of ambivalence. This may suggest that participants preferred to take a neutral position rather than exhibiting negatives stereotypes towards persons with mental disorders. This issue of contradiction and neutral responses were found in further studies conducted previously Putman [27] and Ukpong et al. [20] and his colleagues in Southern Ghana in 2011. For example, Putman's study found conflicting evidence where respondents agreed that having persons with mental disorder as neighbours would be acceptable, but at the same time agreeing that they are undesirable to have in the neighbourhood as they are likely to be violent.

Measures of central tendency and distribution shown that participants reflected less negative stereotypes in community mental health ideology subscale (Md=10%; Mo= 5%; 2 5th percentile=6%: 75th percentile= 13%) than Fear and avoidance (Md=15%; Mo=14%; 25th percentile= 12%: 75th percentile=20%) and Open ended and pro integration (Md=20%; Mo=16%; 25th percentile=16%: 75th percentile=20%) subscales. Also, findings from the current study revealed that participants reflected negative stereotypes on the total scores from the CAMI-S as confirmed by the measures of central tendency (Md= 46%; Mo= 50%; 25th percentile=39%: 75th percentile=53%). These findings are in line with a study conducted by Vedaste and Smith in 2016 on nurses working in a selected District Hospital in Rwanda and Vedaste in 2017 on students' nurses in a selected school of nursing and midwifery in Rwanda. Both studies showed that nurses and students nurses reflected negative stereotypes on Open ended and pro integration,Fear and avoidance, community mental health ideology subscales and the total score.

Associations and correlations

Association between demographic variables and CAMI-S (Subscales & total score):

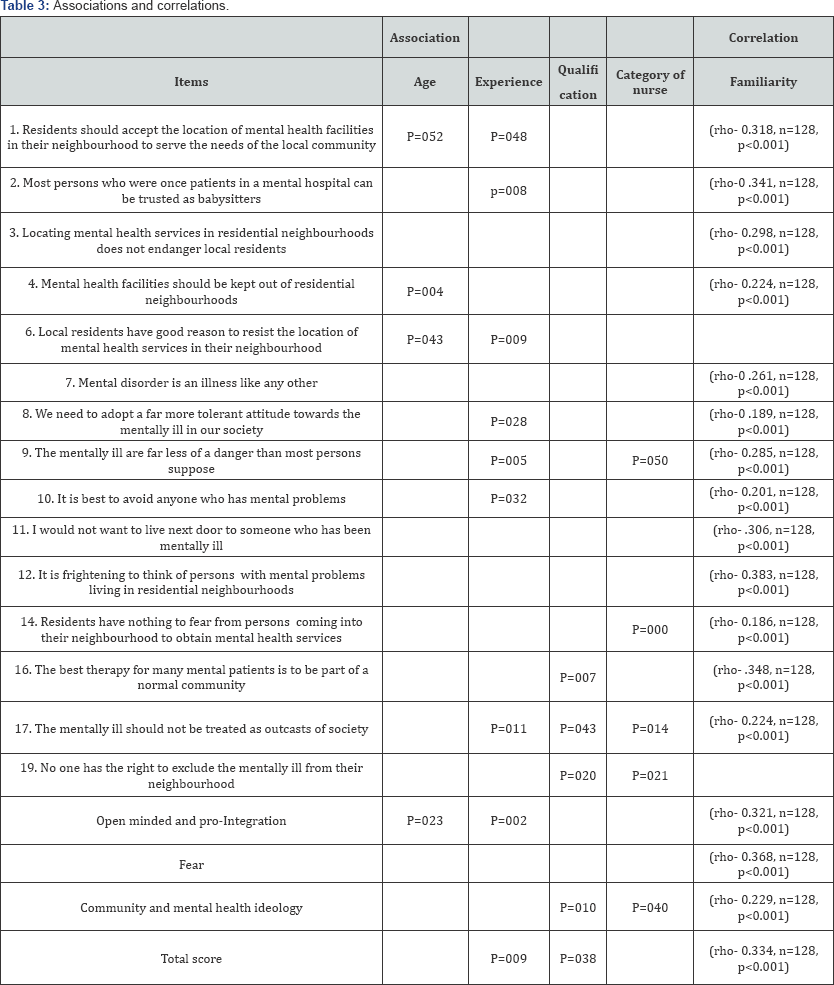

As mentioned in the research methods section, non-parametric tests were used for associations; these include the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis H test [22]. Apart from familiarity (level of contact), demographic variables (gender, experience of nurses, qualification and age of nurses) were seen as independent variables and scale scores on the CAMI-S as dependent variables. Finally, as stated in the methodology section, associations were seen as significant when they were less than 0.05 (P=<0.5). Here, only significant results are presented.

The Mann-Whitney U Test was used to compare specific participant's attitudes towards persons with a mental disorder (scores from the CAMI-S) with gender and category of nurses. Results of Mann-Whitney U Test suggested no significant associations between gender and student nurses stigmatizing attitude towards persons with a mental disorder on the CAMI-S (subscales or total scores). However, significant associations were revealed between category of nurse and CAMIs score and community and mental health subscale (z=-2058; p=0.040, u=1340,000); item 7: The mentally ill are far less of a danger than most persons suppose(z= -329; p=0.050, u=836); item 14: Residents have nothing to fear from persons coming into their neighborhood to obtain mental health services(z= -2132; p=0.050, u=134.000); item17: The mentally ill should not be treated as outcasts of society(z= -2457; p=0.014, u=1292); item19: No one has the right to exclude the mentally ill from their neighborhood (z= -2312; p=0.021, u=1327).

These findings indicate that registered nurses reflected negative stereotypes regarding persons with mental disorder than enrolled nurses working in urban health centres of a selected District Hospital. This is highly indicated by the fact that registered nurses scored higher percentiles than enrolled nurses who scored lower. This is found on items 17 and 19 where registered nurse recorded higher (Md=2; 25th percentiles=1; 75th percentiles=4) and enrolled nurses recorded lower (Md=2, 25th percentiles=3; 75th percentiles=4). Regarding community mental health registered nurses recorded higher percentiles (Md=10; 25th percentile=12; 75th percentiles=6) than enrolled nurses who recorded lower (Md=8; 2 5th percentile=10; 75th percentiles=5) indicating that students registered nurses have a greater extent of negative stereotypes than enrolled nurses regarding community mental health subscale.

As illustrated in Table 3 below the Kryskal Wallis H Test revealed statistically significant associations between qualifications with different items; 16 (p=007); 17(p=043); 19(p=020); and community mental health subscale (p=010) and the total score (p=038).

The highest qualification group recorded a higher median score (Md=3) than other three remaining groups in items 16; 17; 19 while the similar situation was found in community mental health subscale (Md=12) for nurses with bachelor and (Md=10) for nurses with advanced diploma and total score (Md=49) for nurses with bachelor and (Md=48) for nurses with advanced diploma. These results suggest that nurses with bachelor are likely to reflect less negative stereotypes than nurses with advanced diploma. Previous study conducted in Rwanda by Vedaste et al. [15] revealed the same findings suggesting that more experienced nurses reflected less negative stereotypes.

Regarding experience, the Kryskal Wallis H Test revealed statistically significant associations with different items as follows; 1(p=.048); 2(p=0.008); 3(p=0.009); 8(p=.028); 9(p=0.005); 10(p=0.032); 17(p=0.011) and open minded and pro-integration (p=0.002) and total score (p=0.009). The lowest experience (Oyear -8years) recorded a higher media score in all these items than other three remaining groups (9-16; 16-24 and 25 and above) who recorded a low media. These findings indicate that less experience they are, less stigmatizing persons with mental disorder. This goes in line with previous results regarding qualification suggesting that more qualified nurses are reflected less negatives stereotypes. Higher qualified nurses are less experienced due to the fact that Bachelor in nursing in Rwanda started in 2006. This is little different to different studies conducted extensively with international and local studies [28], Barke et al. [21] and Vedaste et al. [15] that are in favour of more experienced participants being less reflecting more negatives stereotypes.

Lastly, the Kryskal Wallis H Test revealed statistically significant associations between age and three items on CAMIs (item1: p=0.052; item4=0 .004 and item 6: p=0.043) and open minded and pro-integration subscale (p=0.023). Central tendency measures that younger nurses (21-30) recorded higher media (item1: Md=2; item4: Md=2; item6:Md=3 and open minded and pro-integration: Md=3) than other groups (31-40; 41-50 and 51 more) who recorded lower media ( item1: Md=1; item4:Md=1; item6:Md=2 and open minded and pro-integration: Md=3). These results indicate that younger nurses reflected less negatives stereotypes than older nurses. Also, these results are congruent with the previous finding on associations of experience, qualification due to the fact that the majority of highly and lower experienced nurses are composed of younger nurses considering the history of training of nurses in Rwanda. Findings from the current study contradicted by previous studies findings such as Adewaya et al. [28] study in Barke et al. [21] and Vedaste et al. [15] and Vedaste [16], which revealed the association between age and negatives stereotypes suggesting that the younger age of participants was significantly associated with high social distance towards the mentally ill. This is bite different with the current study suggesting that younger participants reflected less negative stereotypes.

6.4.2.Correlation of familiarity and negative stereotypes: As it is shown in Table 3, scores achieved on the LOC, level of familiarity, were correlated with scores (CAMIs scores, sub scores and total score). Also, correlation is aiming to identify possible strength and direction of this mediating relationship.

Results with significant correlations (strong, medium and small) are reported (p<0.5), Cohen's guide lines were used to determine the strength of the correlation; small (rho=0.10 to 0.29), medium (rho=0.30 to 0.49) and strong (rho=0.50 to 1.0) cited in Pallant [22].

Firstly, Spearman's rho correlation coefficient was used and revealed evidence of significant negative correlation between some CAMIs scores, sub scores and total score and LOC. Firstly, small negative correlation were found between LOC and the following CAMIs scores as follows; Item4: Mental health facilities should be kept out of residential neighborhoods (rho-0.224, n=128, p<0.001); Item7: Mental disorder is an illness like any other (rho-0.261, n=128, p<0.001); Item8: We need to adopt a far more tolerant attitude towards the mentally ill in our society (rho- 0.189, n=128, p<0.001); Item9: The mentally ill are far less of a danger than most persons suppose (rho-0.285, n=128, p<0.001); Item10: It is best to avoid anyone who has mental problems (rho- 0.201, n=128, p<0.001); Item17: Residents should accept the location of mental health facilities in their neighbourhood to serve the needs of the local community(rho-0.318, n=128, p<0.001); item 14: Residents have nothing to fear from persons coming into their neighbourhood to obtain mental health services (rho-0.186, n=128, p<0.001); Item17: The mentally ill should not be treated as outcasts of society (rho-0 .224, n=128, p<0.001). Also, community and mental health ideology subscale was correlated negatively with LOC (rho-0.229, n=128, p<0.001).

Secondarily, moderate negative correlation was found between CAMIs and LOC as follows; item1: Residents should accept the location of mental health facilities in their neighborhood to serve the needs of the local community (rho-0.318, n=128, p<0.001); item 2: Most persons who were once patients in a mental hospital can be trusted as babysitters(rho-0.341, n=128, p<0.001); item11: I would not want to live next door to someone who has been mentally ill(rho-0.306, n=128, p<0.001); item 12: It is frightening to think of persons with mental problems living in residential neighborhoods (rho-0.383, n=128, p<0.001); item 16: The best therapy for many mental patients is to be part of a normal community(rho-0.348, n=128, p<0.001).

Lastly, moderate negative correlation was also found between subscales and total score and LOC (Open minded and pro-integration (rho-0.321, n=128, p<0.001); Fear and avoidance (rho-0.368, n=128, p<0.001) and Total score (rho-0.334, n=128, p<0.001). These results regarding correlation, suggest that an increase in level of contact (familiarity) correlates with a decrease in scores in CAMIs, subscales and total scare respectively

These results are consistent with findings reported in literature from studies carried out on both the general population and health care providers, suggesting a significant negative correlation between familiarity and stigmatizing attitudes [1517,29,30]. These authors suggest that individuals who have a relative or a friend with a mental disorder do not generally perceive mentally ill persons as being dangerous and therefore desire less social distance from them. However, findings from this study contrast with other previous studies that have been conducted in Africa [31,14]. For example, the study by Smith and Middleton in South Africa in 2010 and James et al. [14] in Southern Nigeria, reported evidence of no relationship between familiarity and the extent of negative stereotyping or desire for social distance [32-34].

Conclusion

The study revealed negative stereotypes amongst nurses working in Urban Health Centres towards persons with mental disorders. Also, the current study revealed high levels of contradictions and neutral responses. These contradictions and neutral responses may suggest a social desirability bias. Also, findings from current study showed that negative stereotypes among nurses were associated with age, experience, qualification and category of nurses.

Lastly, this study revealed a moderate negative correlation between familiarity and negative stereotypes suggesting a mediating relationship between familiarity with persons with mental disorders and negative stereotypes towards mentally ill people. In other words, decreased negative stereotypes were associated with increased familiarity. Familiarity did have a mediating effect on negative stereotypes and may be the foundation for changing attitudes within general health care settings and facilitate the integration of mental health services in general health care facilities in Rwanda from Health Centres to referral health care facilities.

Acknowledgement

First of all, I thank Almighty God for his love and the gift of life to me. Secondarily, a District Hospital which accepted this study to be conducted on Nurses undertaking working in Urban Health centres of its area of catchment. Lastly, IRB/CMHS which provided an ethical clearance to conduct the current study

Conflicts of Interests

This study has not been funded by any institution or organization and it has been conducted by only one researcher thus any conflict of interests cannot be expected.

Author Contributions

The researcher contributed in all phases of the research process; such as conceptual, design, empirical, analysis and dissemination phases.

References

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, et al. (2013) Global burden of deseases attribuable to mental and substance use diseorders: Findings from the global burden of deseases study 2010. Lancet 382(9904): 1575-1586.

- WHO (2011) WHO Mental Health Atlas 2011. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Burns JK (2011) The mental Health GAP in South Africa. A Human Rights Issue. The Equal Rights Review 6: 99-112.

- Callaghan P, Playle J, Cooper L (2009) Mental Health Nursing skills. New York, USA.

- Anthony WA, Farkas M (2009) A primer on the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Process. Boston University centre for psychiatric rehabilitation, Massachusetts, USA.

- Rwandan Ministry of Health (2011) Mental Health Policy in Rwanda. Kigali, Rwanda.

- Ssebunnya J, Kigozi F, Kizza D, Ndyanabangi S, MHaPP Research Programme Consortium (2010) Integration of Mental Health into Primary Health Care in a rural district in Uganda. Africa journal of Psychiatry 13(2): 128-131.

- Lund C, Kleintjes S, Kakuma R, Flisher AJ, MHaPP Research Programme Consortium (2010) Public sector mental health systems in South Africa: inter-provincial comparisons and policy implications. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45(3): 393-404.

- Rwandan Ministry of Health (2009) Health sector strategic plan 20092012. Kigali, Rwanda.

- Kapungwe A, Cooper S, Mayeya J, Mwanza J, Mwape L, et al. (2010) Attitudes of primary health care providers towards people with mental illness: evidence from two districts in Zambia. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 14(4): 290-297.

- Arvaniti A, Samakouri M, Kalamara E, Bochtsou V, Bikos C, et al. (2009) Health service staff's attitudes towards patients with mental illness. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44(8): 658-665.

- Corrigan PW, Powell KJ, Fokuo JK, Kosyluk K (2014) Does Humor influence the stigma of mental illnesses? Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 202(5): 397-401.

- Corrigan WP, Mittal D, Reaves CM, Haynes TF, Han X, et al. (2014) Mental health stigma and primary health care decision. Psychiatry Research 218(1-2): 35-38.

- James BO, Omoaregba JO, Okogbenin EO (2012) Stigmatising attitudes towards persons with mental illness: a survey of medical students and interns from Southern Nigeria. Ment Illn 4(1): e8.

- Vedaste B, Smith AAH (2016) 'In principle, yes, in application, no': Rwandan nurses' support for integration of mental health services. African Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 18(1): 170-182.

- Vedaste B (2017) Student Nurses's Stigmatising Attitudes towards Persons with a Mental Disorder in a selected School of Nursing and Midwifery in Rwanda. Rwanda Journal Series F: Medicine and Health Sciences 4(1): 22-28

- Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Qreen A, Diwan SL, Venn D (2001) Prejudice,Social Distance, and Familiarity with Mental Illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27(2): 219-225.

- Hogberg T, Magnusson A, Ewertzon M, Lutzen K (2008) Attitudes towards mental illness in Sweden: Adaptation and development of the community attitudes towards mental illness questionnaire. Int J Ment Health Nurs 17(5): 302-310.

- Morris R, Scott PA, Cocoman A, Chambers M, Guise V, et al. (2011) Is the community attitudes towards the mentally ill scale valid for use in the investigation of Europian nurses'attitudes towards the mentally ill? A confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Adv Nurs 68(2): 460-470.

- Ukpong DI, Abasiubong F (2010) Stigmatizing attitudes towards the mentally ill: A survey in Nigerian University Teaching Hospital. SAJP 16(2): 56-60.

- Barke A, Nyarko S, Klecha D (2011) The stigma of mental illness in Southern Ghana: attitudes of the urban population and patients views. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(11): 1191-1202.

- Pallant I (2013) SPSS survival manual. Open University Publishers, (5 th edn), Berkshire, England.

- Polit DF, Beck CT (2012) Nursing research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. Wolters Kluwer Health/ Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, (9th edn), Philadelphia, USA.

- Kouta C, Kaite CP (2011) Gender Discrimination and Nursing: a literature review. J Prof Nurs 27(1): 59-63.

- Nordt C, Rossler W, Lauber C (2006) Attitudes of Mental Health Professionals Toward People With Schizophrenia and Major Depression. Schizophr Bull 32(4): 709-714.

- Griffiths KM, Nakane Y, Christensen H, Yoshioka K, Jorm AF, et al. (2006) Stigma in response to mental disorders: A comparison of Australia and Japan. BMC psychiatry 6(21): 1-12.

- Putman S (2008) Mental illness, diagnosis title or derogatory term, developing learning resources for use within a clinical call centre. A systematic review on attitudes towards mental illness. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 15(8): 684-693.

- Adewayu AO, Oguntade AA (2007) Doctor's attitudes towards people with mental illness in Western Nigeria. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 42(11): 931-936.

- Holmes, P, Corrigan P, Williams P, Canar J, Kubiak MA (1999) Changing Attitudes about Schozophrenia. Schizophr Bull 25(3): 447-456.

- Markstrom U, Gyllensten AM, Bejerholm U, Bjorkman T, Brunt D, et al. (2009) Attitudes towards mental illness among health care students at Swedish universities: A follow-up study after completed clinical placement. Nurse Educ Today 29(6): 660-665.

- Smith AAH, Middleton LE (2010) The effect of familiarity on stigma components in potential employers towards people with a serious mental illness in Durban KwaZulu Natal. University of KwaZulu-Natal publishers, Durban, South Africa.

- Mwape L, Sikwese A, Kapungwe A, Mwanza J, Flisher A, et al. (2010) Integrating mental health into primary health care in Zambia: A care provider's perspective. Int J Ment Health Syst 4: 21.

- WHO (2013) Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013-2020. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- WHO (2015) Mental disorders fact sheet No396. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.