Communication Mentors: An Evaluation of a Non-Traditional Training Approach to Address Communication Needs

James W Conroy* and Cory Czuczman

Center for Outcome Analysis, USA

Submission: April 14, 2017; Published: July 17, 2017

*Corresponding author: James W Conroy, Center for Outcome Analysis, 426-B Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083, Pennsylvania, USA.

How to cite this article: James W C, Cory C. Communication Mentors: An Evaluation of a Non-Traditional Training Approach to Address Communication Needs. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017; 1(5): 555574. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2017.01.555574

Abstract

An evaluation of the impacts of 10 years of the Communication Mentors program of Pennsylvania was conducted. The Mentors program was designed to address the extreme imbalance between “demand and supply” of assistance with communication for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Whereas the only accredited and authorized source of such supports has been restricted to one profession, Speech-Hearing-Language, the number of those practitioners is known to be far too small to address the magnitude of the need. A rigorous 9 month training program for non-degreed professionals, paraprofessionals, and advocates was created and conducted each year for 10 years to attempt to address the unmet need. Data were collected from a follow-up survey of all 10 years of graduates of the program.

The survey was designed to identify the numbers of people and families who were supported by the initiative, and how many other professionals and paraprofessionals benefited from “train the trainer” elements of the program. The survey revealed evidence of positive response and broad impact, including direct support provided to approximately 8,000 people and families, plus significant enhancements in trainees’ self-rated knowledge and ability to assist. The survey suffered from a mediocre response rate, and evidence of ultimate outcome (improved quality of communication and/or life among the recipients of supports) could not be collected. Nevertheless, these limited evaluation results provided evidence that specialized communication training outside narrow professional boundaries can provide useful complementary assistance in meeting the communicative needs of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Keywords: Communication; Disabilities; Language; Alternative; Assistive; Augmentative; Intellectual and developmental disabilities; Communication; Speech; Language; Training; Non-traditional; Augmentative; Assistive; Alternative

Purpose and Background

Background 1: Communication supports “supply and demand”

The need for greatly increased capacity to assist people with intellectual, developmental, sensory, and physical disabilities to communicate became more acutely recognized in the latter half of the twentieth century [1]. It was this recognition that led to the creation of the Communication Mentors initiative in Pennsylvania during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The Communication Mentors program imparted knowledge and skills about alternative and augmentative communication techniques to the largest possible pool of helping professionals regardless of academic degrees or certification.

People with intellectual and developmental disabilities are likely to have a need for support, learning, and adaptation in communication. Limitations in communication ability are among the most common and socially important facets of the spectrum [2,3]. This has been recognized since the term “Developmental Disability” was created in the pioneering Developmental Disabilities Act of 1970. Immediately, national surveys found that communication needs were the most often expressed across all the diagnostic categories [4].

By 1984, it was widely recognized that one profession by itself, the Speech-Hearing-Language specialists, could barely even begin to address the tremendous need for communication supports. This was noted with strong emphasis by the National Joint Committee for the Communication Needs of Persons with Severe Disabilities (1992) [5]. The Committee was created as a cooperative effort of the American Speech-Hearing-Language Association and The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps (now known as TASH) with this mission: The symposium participants recognized the need for interdisciplinary efforts in this overall service domain. The interdisciplinary composition of this committee reflects the pervasive importance of communication in all spheres of human functioning and across traditional disciplinary boundaries. The shared commitment to promoting effective communication by persons with severe disabilities thus provides a common ground on which the disciplines represented by the member organizations can unite in their efforts to improve the quality of life of such persons (1993).

This long term cooperative, interdisciplinary, and “across traditional boundaries” legacy is central to understanding the emergence of the Communication Mentors of Pennsylvania. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, experts involved in the disability system had seen a massive level of unmet need, and determined to create a cadre of nontraditional–but qualified and trained–communication support providers.

The Pennsylvania Office of Developmental Programs’ policy [6] stated that: According to recent data made available through the National Core Indicators project and Independent Monitoring or Quality (IM4Q), between 20 and 30 percent of people receiving mental retardation services in Pennsylvania do not use spoken language to communicate. IM4Q results also indicate that there is a formal communication system in place for only approximately one-third of those people who do not communicate using spoken language. This Policy made it clear that the need for communication support, training, learning, assistance, and devices was intense. With an estimated 243,000 Pennsylvanians with intellectual and developmental disabilities [7], and as many as two thirds of whom might benefit from communication supports, it could be safely inferred that the demand greatly exceeded the supply of traditional speechhearing- language professionals. Training nontraditional helpers to disseminate and impart knowledge of techniques was seen as a viable option to increase the supply of communication expertise.

The ODP 2009 Policy went further in mandating “whatever it takes” to get people what they need, in a form they would choose: ODP supports the right of all persons with communication challenges to receive needed supports and services so that they can effectively and more fully communicate. ODP also recognizes its responsibility, and that of its service system partners, to ensure that all individuals registered for and receiving services, even those with significant communication challenges, have:

a. The assistance they need to improve their ability to communicate across all aspects of their life, for a variety of purposes, with different people and in different contexts.

b. Access and choice to services that best match their current and future communication needs and interests.

This policy implied that, when the supply of traditionally degreed and certified communication experts could meet the demand, other nontraditional but evidence based approaches were not only permitted – they were mandated.

In addition to direct demand for communication supports, modern service systems also require expertise to train and educate Direct Support Workers. For example, the New York State Association of Community and Residential Agencies in 2008 [8] set this as its second priority standard for quality: The Direct Support Professional should be knowledgeable about the range of effective communication strategies and skills necessary to establish a collaborative relationship with individuals requiring supports and services. Therefore the Communication Mentors initiative of Pennsylvania included “train the trainer” indirect training goals to spread knowledge further and bring help to more people.

As a final illustration of demand exceeding supply, a relatively recent newspaper article is noted from Pennsylvania Daily Review in 2012 [9], entitled “Districts struggle to find speech therapists.” As school districts wade through hundreds of job applications from teachers, there is one type of job seeker superintendents wish they could find: speech-language pathologists. Even the public schools cannot meet their demand for traditional communication supports. Moreover, the schools are in competition with adult populations with developmental disabilities, brain injury, other illnesses, sensory disabilities, and conditions related to aging.

The degree of unmet communication needs has been clear, but resistance to nontraditional approaches arose from the traditional Speech-Hearing-Language profession. This resistance may be viewed in context as the normal territorial response of a profession to protect its livelihood and expertise. This kind of resistance to nontraditional expertise has been seen since the rise of Guilds in the middle ages. Guilds (and now professional associations) generally serve two purposes, protection of the guild members including income and prestige, and protection of the consumers from unqualified practitioners.

Public officials are charged with meeting human needs, and may in some cases carefully overrule the professional needs in favor of the consumers’ needs. Specifically, public policy would seem to require this overruling when:

a. Legitimate consumer needs are not being met by the traditional profession, and

b. Legitimate alternatives with demonstrated benefits can be found.

The Communication Mentors efforts were founded on the belief that both conditions were, in fact, present in the Pennsylvania system.

Background 2: Emergence of the communication mentors of Pennsylvania

Based on many years of observation of unmet needs, the leadership of one specialized training agency, Networks for Training and Development, decided to take action in 2003. They designed a nine month course of interactive didactic learning and field experience that, from their website, was intended to “purposefully target and shift attitudes about disability, teach newer ideas about abilities, and help participants become more familiar and comfortable with Assistive Technology and Augmentative and Alternative Communication.” The idea of having real world experiences with people seeking supports was an integral part of the Mentors program. One of the program’s important guiding principles was stated as “everyone communicates,” which was considered in those days to be an innovative and nontraditional belief. It was believed to distinguish the Mentors from older style Speech-Hearing- Language education, which had encountered great difficulty in working with people who had no language at all, but still needed modes of communication.

Similar programs using non-specialized support workers and advocates as mentors with people with disabilities have had moderate to high success rates, and have suggested a need for more programs of this kind, where demand far exceeds supply [10,11]. Communication Mentors was unique in its focus on communication needs, which has often been defended as the sole province of a particular profession and degree.

The agency that created and operated the Communication Mentors initiative did so without public agency funding. The leadership of Networks for Training and Development created the initiative as part of their values-based mission to assist a system replete with unmet need.

The Mentors are described on their website as “committed to supporting all people in raising their voices, exercising choice and control, and promoting independence by utilizing desired ways of communicating.” Communication Mentors are graduates of The Communication Mentors’ Course™, which was developed to “build capacity” in local areas by training interested people in how they might help others who have unrecognized or not fully expressive communication to find or expand their voice through the use of Assistive Technology (AT) and Augmentative/ Alternative Communication (AAC). Through an almost yearlong course of study and real world practice in what AT/AAC is, the larger issues of choice and control faced by people who are seen as “voiceless,” and how we can all better hear everyone’s communication, Communication Mentors are born.

By 2013, the Mentors Courses had included more than 190 individuals. They came from many working situations and disciplines: Direct Support Workers, agency managers and administrators, social workers, psychologists, nurses, various therapists (SLP’s, OT’s, Behavioral Therapists, etc.), community integrated employment staff, educators, early intervention specialists, supports coordinators, attorneys, researchers, family members, and individuals who use AT/AAC themselves who wanted to help others learn.

The Mentors Program posted a goal of creating and maintaining a statewide network that works across boundaries of agencies, counties, and systems to provide training and information sessions, hold various Assistive Technology Clinics for individual exploration, work with people and their supporters over time, and provide accessibility reviews for increased independence and control.”

From the beginning, the Communication Mentors Course was supported by fees and the contributions of Networks for Training in staff time and in-kind donations. Mentors have not received Pennsylvania funding or routine private foundation funding. It should be viewed as a pilot project, to be evaluated for efficacy, and future support for Mentors Courses or courses similar to them should be based on findings of outcomes and impacts.

Methods

Survey design and purpose

Ten years after the Communication Mentors initiative began, it was deemed appropriate to retain an independent organization to design and conduct a follow-up survey of the Mentors. The survey would invite responses from all 170 graduates of the program over the preceding 10 years. Its central purpose was to acquire simple descriptive data about the success and the impacts of the initiative. The specific purposes of the survey were to:

a. Obtain estimates of the numbers of individuals assisted and trained by the Mentors.

b. Collect perceptions about the outcomes and impacts of Mentor activity.

c. Gather information and ideas for future alteration and/ or expansion of the initiative.

Instruments

The Independent Evaluator first requested input from the Mentors team (Networks for Training and Development managers, trainers, graduates, and advocates). A body of potential questions was accumulated. Each question was cast into appropriate form and format for survey research (such as adhering to the rule of one-question-one-concept, no jargon, and simple sentence structure). The questions were then submitted to a “voting” process among the team members to isolate the most important ones, and about which there was the strongest agreement.

The penultimate set of questions contained 21 items, of which 6 were about respondent demographics and work history, 4 were about involvement in the Mentors program, 3 were estimations of numbers of people and families assisted or trained, 5 were scales about Activity, Experience, Attitudes, Behavior, and Need; 2 were about recommendations for the future of the initiative; and 1 was a request for an illustrative “story” about a person, family, or systems interaction.

There were two pilot test rounds with volunteers familiar with, but not graduates of, the program. Items that were unclear were rewritten and retested. Final revisions were completed and the survey was posted on Survey Monkey™ in 2013.

Procedures

The emailing list of Communication Mentors course graduates was used to invite the graduates to respond to the survey. Invitations were sent to 194 Mentors graduates. Responses were accepted until August 1, when a reminder email was sent out to the graduates. The survey was closed in September of 2013. Valid responses were received from 32 (16.5%).

Sampling

The response rate was a point of concern in this survey, although not unexpected because of the long period covered-up to a decade could have passed since a graduate respondent took the training. The margin of error for 32 units sampled from a Universe of 194 is plus or minus 15.1%. This is not as good as the much preferred rate of plus or minus 5%. (A 5% margin of error would have been reached with 122 out of 194). However, whether it is 5% or 15% is merely a general guideline about confidence, not a black and white rule of scientific acceptability.

In this regard, it is useful to keep in mind that the far greater threat to validity of a social survey is the self-selection of the respondents. While the entire math in sampling theory assumes that the respondents are selected at random, this is never true. As much as we tend to ignore this, and cover it up with margin of error math, social surveys practically always have biases larger than sampling error-and these are sources of error that we cannot even estimate.

We suggest viewing the results as informative and “best available” information. In precise sampling terminology, the odds are about 9 out of 10 that our estimates from the sample survey are within 15% of the true values for the population.

Analysis

The data from Survey Monkey were downloaded as an Excel™ file, and converted to SPSS™ (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for analysis. Only the simplest procedures were required-frequencies and descriptive tables.

Results

Results 1: Characteristics

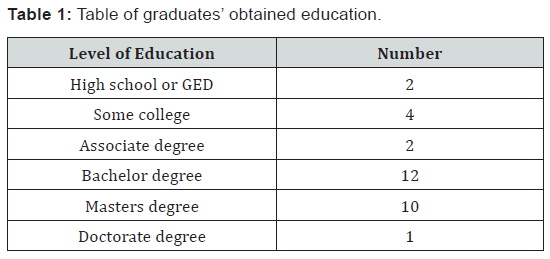

The survey did not collect age, ethnicity, or gender, based on the viewpoint that those characteristics were not important for estimation of overall impacts. Graduates were asked about level of education and field of specialization. The graduates clustered at the baccalaureate and master’s degree levels, as shown in (Table 1).

The graduates reported a variety of occupational categories, from disability advocate to human services worker. The most frequent occupation reported (n=11) was “social work.” Some of the answers, such as “Communication Specialist” were interesting, in that the formal discipline of Speech-Hearing-Language was not mentioned, but the word “Communication” was. The simple English response “I assist people to be understood more clearly and effectively” was similarly quite nontraditional, and yet quite descriptive.

We asked why individuals chose to take the Communication Mentors Course in this form: “Can you give us a sentence or two explaining why you got involved? (It may be difficult to say this so briefly, but please give it a try.)” Some notable responses were: “The need to understand others and ensure that everyone’s voice is heard”; “To help individuals live their lives the way they choose to live”; “I believe that families, support staff, and agencies are continually missing intentional communication through behavior and environment”; and “To give the people in need of services a voice”. To make sure all their wants and needs can be heard.” These responses generally indicated a common theme of the perception of a large unmet need.

Results 2: Communication mentors training and supports provided

The survey asked “About what percentage of your working or advocacy time is devoted to communication issues?” The answers ranged from 0% (n=1) to 100% (n=5). The average was 38%.

Next the Mentors were asked to provide some approximate numbers to reflect impacts since taking the Course. Based on the responses to the question, “Can you estimate how many people (or families) you’ve worked with directly on communication issues since Mentors training?” the mean response was 40 individuals. The responses to the question “Can you estimate how many people you have provided training to-or lectures, presentations, small group learning, etc. since Mentors training?” gave a mean of 140 individuals. These two averages can be used to very roughly estimate the level of magnitude of “lives touched” either by direct communication supports or by training others about communication. The sample numbers yield an estimate of approximately 8,000 people receiving direct communication assistance and support over the 10 years, and the number of people that have received training, presentations, lectures, etc. is approximated at about 27,000.

As another impact indicator, the survey asked “How do the numbers (per year) compare to what you did before Mentors training?” The Mentors indicated that their numbers had definitely gone up; 21 Mentors thought their numbers had increased, 5 thought they had stayed the same, and 4 reported a decrease since the course.

Results 3: Perceptions of impacts and outcomes

The remainder of the survey questions was aimed at perceptions of skills, impacts, and outcomes.

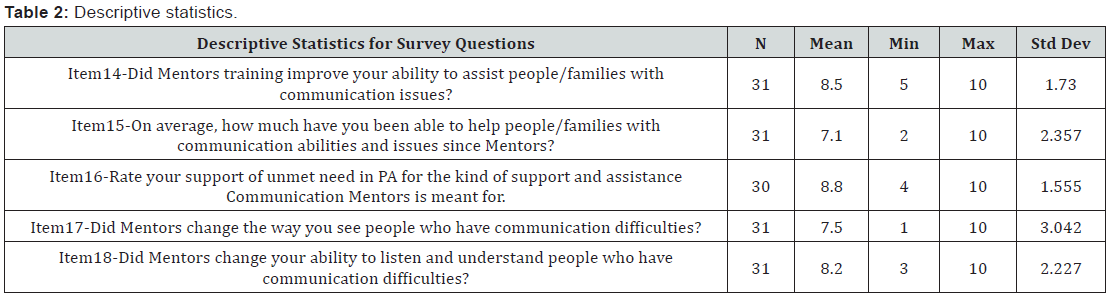

Question 14 asked: “On a scale from 1 to 10, how much did Communication mentors training improve your ability to assist people (or families) with communication issues?” Responses showed a mean of 8.5. The descriptive statistics can be seen in (Table 2). The responses showed that Mentors believed that the Communication Mentors Course brought about major increases in their ability to assist people. There were no responses below “Some,” and nearly half were at the very top of the 10 point scale. These were strong and clear positive self-reports.

Question 15 asked about actual experience in helping people and families since the Course: “On the average, how much have you been able to help people (or families) with communication abilities and issues since Mentors?” Responses had a mean of 7.1. Thus the graduate Mentors reported being able to help people and families positively, with the most frequent responses being “Some” and “A Great Deal.” There were only two responses on the low end of the 10 point scale.

Question 16 asked about perceived need in Pennsylvania for programs like Mentors: “Please rate your perception of the unmet need-in Pennsylvania-for the kind of support & assistance Communication Mentors is intended for.” The responses were positive with a mean of 8.8. The minimum response to this unmet need was a 4, showing that there were no responses of “not at all.” The Mentors clearly believed that the reason for the Communication Mentors training, when it began in 2003, was still strongly present in Pennsylvania by the time of our survey in 2013. More than half rated the unmet need as a “10” at the top of the scale.

Question 17 asked “Perception: Did Mentors training change the way you see people who have difficulty with communication?” The answer was clearly on the side of “Yes,” with nearly half the graduates saying “A Great Deal” and only four saying “Not At All.” The mean was 7.5. It was safe to conclude that the Course had a strong positive impact on perception and therefore interpersonal relationships between Mentor and support recipients.

Question 18 asked “Listening: Did Mentors training change your ability to try to listen and understand people who have difficulty with communication?” This was viewed as a central issue on the Networks stated belief that listening was essential before knowing what communication methods and alternatives might suit the individual. The mean response for item 18 was 8.2. The Mentors thus reported that they learned and grew in their ability to listen and understand. Most of them learned a lot in this area, with over half giving the highest possible rating. This is a key finding in view of some of the predominant thinking in the field which puts “Learning to Listen” at the top of the hierarchy of support skills in modern systems [12].

Whether any of these item means were significantly different from the others was explored with Paired T-Tests. This analysis could suggest areas of high versus low scores, i.e., strengths and weaknesses in the Mentors curriculum. The analysis revealed that Items 14 and 15 were significantly different, t(30)=3.351, p< 0.002, and Items 15 and 16 were also significantly different, t(29)=4.029, p< 0.000. Basically, the statistical tests simply showed that some of the ratings were “significantly higher” than the others, with the areas that might benefit from attention and improvement being 15 “amount of help given” and 17 “change the way you see people.” The highest ratings were given to Items 14 and 16, that is, the perception that Mentors training improved the participants’ ability the assist people and families with communication issues, and the belief in the magnitude of unmet need for communication assistance and support.

At the end of the survey, mentors were solicited for short qualitative accounts of whatever they wished to share (be it failures, victories, or barriers). The responses tended to have similar patterns: an urgent call to fill the unmet need (“The need to listen to what people are communicating is essential. How we go about it, as long as it is effective and makes a positive difference in the person’s life-including their support staff and especially within the family is the ultimate goal. This approach teaches one to really notice what typically hadn’t been given a term, voice, or label before.”), a desire to give individuals a voice (“We cannot stand by and allow people to go unheard! The more we do to raise awareness the more we give others the chance to raise their voices!”), or personal accounts of putting the Mentors skills into use (“One of the people I worked with used the yes/ no switches and “talked” to us. He had been institutionalized and ignored for decades. His smile and laughter after this experience will last with me forever!”).

Discussion

An evaluation of the Pennsylvania communication mentors courses was conducted via a web survey of 10 years of graduates. The courses began in 2003 in response to a perceived need for assistance with individual communication issues that far outstripped the ability of the traditionally degreed & certified Speech-Hearing-Language profession to meet, and continued each year until the evaluation in 2013.

The survey of 32 Mentors enabled calculation of rough estimates of the impacts of 194 Mentors in Pennsylvania over the 10 year period. The numbers were impressively large. Approximately 8,000 people with communication needs, and their families, have been reached in some way, and roughly 27,000 people have been the beneficiaries of some kind of training, or workshop, or seminar, or on-the-job instruction via the Mentors.

There were five questions about perceptions of Course impacts on the Mentors, and of Mentor impacts on people and families in need. All five showed evidence of strong impacts and outcomes. The five areas were:

a) Improved ability to assist people and families with communication issues.

b) Actual helping of people and families with communication issues.

c) Perception of ongoing unmet need for communication assistance in Pennsylvania.

d) Positive changes in perception of people with communication issues.

e) Ability to listen to and understand people with communication issues.

Because the data collected showed such positive reports of impacts and outcomes, along with the high degree of positivity in the qualitative comments, we may conclude that it is proper to infer a high degree of success of the Communication Mentors Courses.

A limitation of these findings is that there were 194 people who had completed the Mentors courses over the 10 year period, yet responses had been received from only 32 people. This response rate was not unusually low for long term follow-up evaluations, but should nevertheless be viewed as a limitation. Because of the limitation with generalization, it is best to interpret our findings from this survey with caution. Another study limitation would be that the survey method is inherently based on self-report, and the threats to the validity of these data should be considered, including social desirability bias. Survey findings here, like all those derived from surveys, should be interpreted with caution in view of this limitation.

The estimates of extensive unmet need suggest that nontraditional programs like the Communication Mentors are important. In the realm of communication training and supports among people with disabilities, it appears that demand far exceeds supply. However, non-traditional approaches like Mentors that threaten professional and credentialed prerogatives and territoriality have often been met with some resistance and controversy. The Mentors program was subjected to such resistance, which took the form of years of anonymous complaints to statewide professional review Boards. The complaints alleged that the Mentors were practicing professional activities without proper licensing and certification. After nearly a decade, these anonymous complaints were revealed by the state to have arisen from a University that trained and granted credentials in Speech- Hearing-Language.

The positive results of the present program evaluation strongly suggest that a program to train nontraditional communication helpers, like the Mentors, can address some of the vast pool of unmet need. The next stage of research should include recipient outcomes-measuring actual improvements in the quality of individual communication and qualities of life associated with enhanced communication.

References

- Glennen SL, De Coste (1997) Handbook of Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Singular Publishing, San Diego, USA.

- Abbeduto L (2003) International Review of Research in Mental Retardation Volume 27. Language and Communication in Mental Retardation, pp. 1-325.

- Sigafoos J (1999) Creating opportunities for augmentative and alternative communication: Strategies for involving people with developmental disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication 15(3): 183-190.

- Conroy J, Derr K (1971) Survey and analysis of the habilitation and rehabilitation status of the mentally retarded with associated handicapping conditions and problems. Report to Social and Rehabilitation Service, DHEW, on the potential impacts of the new Developmental Disabilities Act. Decision Control Inc, Bethesda, USA.

- National Joint Committee for the Communication Needs of Persons with Severe Disabilities (1992) Guidelines for meeting the communication needs of persons with severe disabilities.

- Casey KT (2009) PA Department of Public Welfare, Office of Developmental Programs, Communication and support services.

- Larson SA, Lakin KC, Anderson L, Kwak Lee N, Anderson D (2000) Prevalence of mental retardation and/or developmental disabilities: Analysis of the 1994/1995 national health interview survey disability supplements. Am J Ment Retard 160(3): 231-252.

- Direct Support Professionals (2008) The Frontier of Change. New York State Association of Community and Residential Agencies, Albany, USA.

- Hall SH (2012) Districts struggle to find speech therapists. The daily review.

- Burgstahler S, Cronheim D (2001) Supporting peer-peer and mentor-protege relationships on the internet. Journal of Research on Technology in Education 34(1): 59-74.

- Dossa A, Capitman JA (2011) Lay health mentors in community-based older adult disability prevention programs. Res Gerontol Nurs 4(2): 106-116.

- Lovett H (1996) Learning to listen. Positive approaches and people with difficult behavior. Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, USA.