Supporting African American Grandmother Caregiver’s Health Through Social Media

Kathryn Freitag1, Bhumika Devnani1 and Eva Vivian2*

1Student, University of Wisconsin Madison School of Pharmacy, Rennebohm Hall, 777 Highland Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin, USA

2Professor, University of Wisconsin Madison School of Pharmacy, Rennebohm Hall, 777 Highland Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin, USA

Submission: May 23, 2024; Published: May 31, 2024

*Corresponding author: Eva Vivian, Professor, University of Wisconsin Madison School of Pharmacy, Rennebohm Hall, 777 Highland Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin, USA

How to cite this article: Kathryn Freitag, Bhumika Devnani and Eva Vivian*. Supporting African American Grandmother Caregiver’s Health Through Social Media. Curre Res Diabetes & Obes J 2024; 17(3): 555965.DOI: 10.19080/CRDOJ.2024.17.555965

Abstract

Almost one third of African American (AA) grandmothers care for their grandchildren regularly. Many of these caregivers have obesity and care for a grandchild who is also obese. Grandmother caregivers influence their grandchildren’s eating patterns by modeling their own eating behaviors and food preferences. Grandmother caregivers may benefit from evidence-based diabetes prevention programs that prevent diabetes through healthy eating, increased physical activity, and weight loss. Changes in these caregivers’ lifestyles may influence the health behaviors of their grandchildren, thus reducing the alarming obesity trend among AA grandchildren. Healthy Outcomes through Peer Educators (HOPE) is a peer support program designed to enhance the diabetes prevention program by allowing grandmothers who reside in the same community an opportunity to provide each other with knowledge, experience, emotional, social, and practical help while engaged in the program. Twenty-eight HOPE participants were invited to participate in a FaceBook page designed to create a platform where they could share strategies for improving eating behaviors and increasing physical activity. Eight participants who accepted the invitation enjoyed a variety of communication methods (e.g., in person, virtual platforms, and social media). Participants who declined to engage in social media identified lack of time and security/privacy as barriers. Incorporating a variety of communication methods in diabetes prevention may increase social interaction and increase participation and retention in the program.

Keywords: African American; Grandmother; Caregiver; Children; Diabetes Prevention Program, Obesity; Prediabetes; Social Media; Peer Support

Abbreviation: AA: African American; HOPE: Healthy Outcomes through Peer Educators; DPP: Diabetes Prevention Program; IRB: Institutional Review Board

Introduction

According to the United States census, 31% of African American (AA) grandparents, mostly AA grandmothers, living with grandchildren, are responsible for the care of their grandchildren [1]. This figure may underestimate the percentage of grandparent caregivers due to a long history of informal kinship care rooted in West African family tradition which is the most common childcare in AA families to date [2].

Over 50% of AA grandmother caregivers have obesity, many whom care for a grandchild who is also overweight or obese [3-5] Grandmothers influence their grandchildren’s eating patterns by modeling their own eating behaviors and food preferences [5-9] African American grandmothers who are caregivers for their grandchildren may benefit from health interventions delivered through social media and improvements in their lifestyles may translate to benefits in reducing the alarming obesity trend among African American grandchildren [10].

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) is an evidence-based lifestyle change program found to prevent or delay the development of diabetes through lifestyle changes (e.g., dietary changes and increased physical activity) resulting in modest weight loss) [11]. However high attrition and low attendance among AA participants occurred in DPP translations, resulting in suboptimal outcomes [12]. Healthy Outcomes through Peer Educators (HOPE) is a peer support program designed to enhance the DPP by allowing grandmothers who reside in the same community an opportunity to provide each other with knowledge, experience, emotional, social, and practical help while engaged in the program [11]. The HOPE intervention is a blended program that is offered in person and virtually using Zoom platform, making it readily accessible to AA grandmother caregivers residing in lowincome communities and increased retention and participation in the program for caregivers with numerous responsibilities [13].

Recent national surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center reported that 47% of internet users ages 50-64 and 26% users ages 65 and older now use social networking sites [14]. Social media platforms like Facebook groups could be a resource for improved physical and mental well-being in older adults. The HOPE plus DPP intervention assessed the acceptability of social media, specifically Facebook (FB) as a motivational tool for AA grandmother caregivers. This paper summarizes benefits and challenges of using FB as a social educational tool for AA grandmother caregivers 50 years and older.

Methods

Formation of the Facebook Group

A detailed description of the methods of the HOPE study can be found in a previously published article [13]. The HOPE Community Advisory Board consisting of 4 community members and 3 members of the study team conferred to discuss a virtual reality-based social platform that would allow members to share videos of engagement in healthy behaviors, document daily progress and actively engage in discussions to motivate each other to lead a healthy lifestyle. The advisory board decided to incorporate a Facebook group as a space where participants could encourage and support one another.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison Minimal Risk Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the addition of the FB page to the study protocol. All HOPE Study participants (64.6 ± 5.92, n=28) were invited to participate in the 100 Day Challenge FB group via an email invite which included a link to join the closed community group on Facebook. Participants were also informed about the FB group during their weekly DPP sessions. The invitation emphasized the voluntary nature of participation.

Interview Process

Participants were categorized into two groups: 1) Active Users who actively engaged with the HOPE Study Facebook page by viewing, commenting, or responding to posts and 2) non-users who did not accept the Facebook page invitation or engage in the Facebook page. Four active users and 4 non-users were randomly selected to participate in semi-structured interviews. The participants were asked about the types of technology, if any, they use as a form of communication. They were also asked how often they engage in social media, challenges faced, and acceptance of social media as a way of communicating with family and peers.

Interview Procedure

Participants were contacted for a semi-structured interview, conducted by phone to ensure accessibility and convenience. Each interview, lasting approximately 15 minutes, was audio-recorded with participants’ explicit consent. The use of a standardized set of questions facilitated a consistent approach in gathering data from both user groups.

Data Analysis

Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim, and content analysis was employed to identify common themes and patterns related to grandmothers’ interaction with social media and technology, particularly with the FB page. This qualitative approach allowed for a nuanced understanding of participants’ experiences and perceptions.

Results

Sixty one percent (n=17) of the study participants accepted the invitation and engaged with the FB page, either by posting videos, commenting, or reacting to posts.

Four of the 17 study participants who engaged with the FB page and four of the 11 study participants who did not accept the FB invitation were randomly selected and invited to be interviewed. All women invited to be interviewed accepted. The active users were labeled as participants #1-4 and non-active users #5-8.

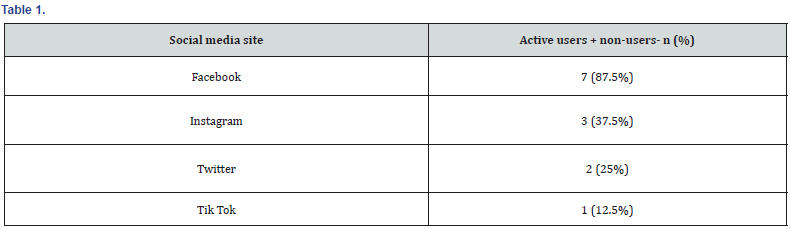

The interviewees were asked which social media platform they used regularly. Facebook emerged as the most utilized social media platform with 7 out of 8 women interviewed using the site Table 1.

Perspectives of Active Users and Non-Users

The active users (n=4) had mixed views about the benefits of participating with the FB page. Two actively posted, while two engaged by commenting on or reacting to posts. Participant 1, who posted on the FB group, found it informative but not particularly motivational, expressing, “I have a motivational wall in my home that I made myself, that’s my motivation.” Conversely, participant 2, who posted messages on FB, found the group inspiring, noting, “...it made me feel like, you know, I needed to do more cause some of the members were doing more than what I was doing.” Participant 3 initially participated by offering words of encouragement by adding comments to FB posts.

She indicated that she disengaged after a few weeks, “It was just giving words of encouragement to others’ accomplishments. So, then I just drifted off. Not even checking anymore. Not even looking into it.” When asked about the helpfulness of the FB page, she remarked, “I just felt it was just another chore. More on my to-do list. I am sure that if I would have used or utilized it that it would have been very helpful.” Participant 4 expressed concerns about identity theft stating “my friend made the mistake of posting personal information on FB. Someone hacked into her account and stole her bank card information. She got off FB and told everyone-get in touch with me the old fashion way-call me.”

While the non-users (n=4) indicated that they were comfortable with digital technology, they chose not to engage in the FB social page due to lack of interest and competing caregiver responsibilities. Participant 5 indicated she did not have a FB account and expressed a preference for texting as a form of communication versus social media (e.g., FB participation), stating, “...I did communicate with one or two people in the group who were using Facebook… I texted them occasionally.” Participant 6 was unable to commit the time to engage with FB group due to caring for 9 grandchildren. Participant 7 declined to participate due to numerous competing responsibilities, stating” I don’t really care to be in the group.” Participant 8 stated “I am on a computer all day at work. I really prefer to meet in person or talk to people on the phone.”

Discussion

This study provides insight into the willingness of grandmother caregivers to engage with social media platforms for support and community-building. While 61% of the women signed up for the Facebook page, fewer than 25% engaged in social communication. A Pew Research survey reported that 55- to 64-year-olds make up just 11.6% of Facebook’s total user base, while those aged 65 and above represent just 12%. [15].

The COVID 19 pandemic limited social interaction, resulting in a greater reliance on technology, particularly for older adults. AARP reported that 4 out of 5 adults aged fifty and above rely on technology to stay connected and in touch with family and friends [16]. While cost, awareness/lack of knowledge, and privacy concerns are the top self-reported barriers holding older adults back from adopting new technology, [15] the grandmother caregivers enrolled in the HOPE study had access to internet and engaged in some form of technology (e.g., video chats, texting, and emailing) as a means of communication with family and friends.

This study highlights the importance of accommodating different preferences for virtual communication, particularly social media. A variety of communication methods (e.g., in person, virtual platforms, and social media) can be used to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors. Addressing common barriers, such as cost of internet access, lack of knowledge, and security/privacy may increase older adults’ willingness to engage in social media. Promoting digital literacy and providing technical support can provide older adults with the confidence to engage in social media and increase social connections.

References

- Bureau UC (2016) Grandparents and Grandchildren. The United States Census Bureau.

- Scannapieco M, Jackson S (1996) Kinship care: The African American response to family preservation. Social Work 41(2): 190-196.

- Fast Stats - health of Black or African American population (2023) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL (2017) Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief 288: 1-8.

- Johnson VR, Acholonu NO, Dolan AC, Krishnan A, Wang EH, et al. (2021) Racial Disparities in Obesity Treatment Among Children and Adolescents. Curr Obes Rep 10(3): 342-350.

- Prokos AH, Keene JR (2012) The life course and cumulative disadvantage: Poverty among grandmother headed families. Res Aging 34(5): 592-621.

- Lipscomb RC (2005) The challenges of African American grandparents raising their grandchildren. Race, Gender & Class 12(2): 163-177.

- Meredith Minkler, Esme Fuller-T (2005) African American Grandparents Raising Grandchildren: A National Study Using the Census 2000 American Community Survey. J Gerontology: Series B 60(2): S82-S92.

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE (2013) African American Caregiving Grandmothers: Results of an Intervention to Improve Health Indicators and Health Promotion Behaviors. J Family Nurs 19(1): 53-73.

- Sutherland ME (2021) Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among African American Children and Adolescents: Risk Factors, Health Outcomes, and Prevention/Intervention Strategies. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 8(5): 1281-1292.

- William CK, Elizabeth Barrett-C, Sarah EF, Richard FH, John ML, et al. (2002) Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346: 393-403.

- Samuel‐Hodge CD, Johnson CM, Braxton DF, Lackey M (2014) African Americans and DPP translations. Obes Rev 15(Suppl 4): 107-124.

- Vivian EM, Chewning BA, Voils CI, Brown RL (2024) Healthy Outcomes through Peer Educators: Feasibility of a peer support diabetes prevention programme for African American grandmother caregivers. Diabetes Obes Metab.

- Madden M (2010) Older Adults and Social Media. Pew Research Center 2010.

- Dixon SJ (2024) Share of Facebook Users in the United States as of January 2024 by age group.

- (2021) Tech Usage Among Older Adults Skyrockets During Pandemic.