Cardiovascular Parameters of People with Diabetes Mellitus: An Intervention Study

Autran José da Silva Júnior1, Fernando Inocêncio Brito2 and Lilian Cristiane Gomes3*

1Physical educator, PhD in Motor Science, Professor and coordinator of the undergraduate course in Physical Education at the University Center of the Guaxupé Educational Foundation (UNIFEG), Guaxupé, Minas Gerais, Brazil

2 Physical educator, Professor at Dom Inácio College at the University Center of the Guaxupé Educational Foundation (UNIFEG), Guaxupé, Minas Gerais, Brazil

3Nurse, PhD in Sciences, Professor and coordinator of the undergraduate course in Nursing at the University Center of the Guaxupé Educational Foundation (UNIFEG), Guaxupé, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Submission: March 20, 2019; Published: April 25, 2019

*Corresponding author: Lilian Cristiane Gomes, Nurse, PhD in Sciences. Professor and coordinator of the undergraduate course in Nursing at the University Center of the Guaxupé Educational Foundation (UNIFEG). Guaxupé, Minas Gerais, Brazil

How to cite this article: Autran José da Silva Júnior, Fernando Inocêncio Brito, Lilian Cristiane Gomes. Cardiovascular Parameters of People with Diabetes Mellitus: An Intervention Study. Curre Res Diabetes & Obes J. 2019; 10(4): 555793. DOI: 10.19080/CRDOJ.2019.10.555793

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases are the main chronic complication of diabetes mellitus. The literature shows that educational interventions can promote, among other benefits, the reduction of cardiac risk, especially when they include, in practice, lifestyle changes. The present study aimed to evaluate the effects of an educational program, centered on self-care and concurrent physical training, on the cardiovascular parameters of 15 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. There was a higher frequency of elderly, female, low educational level, a diagnosis time less than 10 years and the use of oral antidiabetics. For heart rate, the results indicated presence of satisfactory variability. A reduction in mean values of systolic and diastolic blood pressure (p <0.0001) was observed, suggesting an improvement in ventricular strength and the capacity of peripheral vasodilation. It is concluded that the proposed educational program, by including the regular and well-oriented practice of concurrent physical exercise, contributed to self-care and improvement of cardiovascular parameters, since the same physical effort resulted in lower cardiac stress due to inducing cardiovascular physiological adaptations and muscular.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus; Cardiovascular diseases; Health education; Self-care; Physiological Adaptations; Physical training; Physiological adaptations and muscular; Cardiac stress; Physical exercise; Systolic and diastolic blood pressure; Oral antidiabetics; Metabolic disorders; Chronic hyperglycemia

Abbreviations: CVDs: Cardiovascular Diseases; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure; HR: Heart Rate; T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; EP: Educational Program; OADs: Oral Antidiabetic Drugs; FICF: Free and Informed Consent Form; BP: Blood Pressure; AADE: American Association of Diabetes Educators; BMI: Body Mass Index

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and diabetes mellitus (DM) are diseases that are characterized by high morbidity and mortality in Brazil and in the world [1,2], leading to limitations and physical disabilities that lead to a reduction in quality of life, as well as high financial and social costs [2,3].

The magnitude of the problem lies in the fact that DM is considered an independent risk factor for CVDs [4], since diabetic individuals have twice the risk of death due to this condition, when compared to non-diabetics [4-6]. Chronic hyperglycemia leads to metabolic disorders and consequent dysfunctions in blood vessels, heart and brain, among other organs [7].

In Brazil, the self-reported prevalence of DM in the adult population is estimated at 7.5% [8] and represents 5% of the disease burden in the country [9]. Its alarming prevalence projections, coupled with its significant impact on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, make DM one of the most relevant diseases in the list of chronic diseases [10]. Thus, cost-effective strategies for its adequate management and prevention of its complications have been a priority in the public health agenda. The classic study, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group, showed that every 1% reduction in glycated hemoglobin contributes to reducing the relative risk of the following clinical outcomes related to DM: amputation or death from peripheral vascular disease (43%), microvascular complications (37%), any outcome including death (21%) and acute myocardial infarction (14%) [11]. In addition to glycemic control, there are other fundamental components for the cardiovascular health of people with DM, among which the practice regular physical activity and blood pressure control [3]. However, these components tend to show better results when inserted in a context of health education [12].

The benefits of educational programs on glycemic control are well established in the literature [13-15], however, there are still few studies evaluating these benefits in relation to the cardiovascular parameters of diabetic individuals, especially those that include physical exercises and in population samples Brazilians. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of an educational program, centered on self-care and concurrent physical training, on heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus 2 (T2DM).

Materials and Methods

Design and ethical aspects

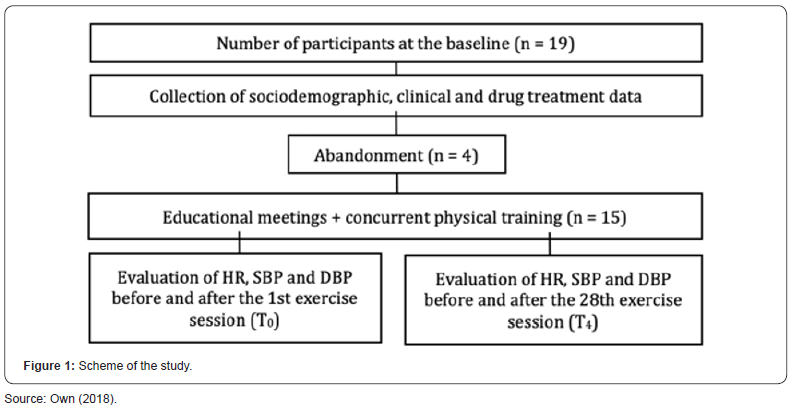

The present study was part of a project titled “Evaluation of an educational program for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, focusing on the practice of physical activities and foot care,” approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Center of the Guaxupé Educational Foundation (UNIFEG), Guaxupé, Minas Gerais, Brazil, protocol nº. 2,029,352, of May 3, 2017. This is a longitudinal and interventional study, that was developed at the Centre for the Study of Health and Physical Education (CESEF) of the UNIFEG during the period from August to December 2017, with a single comparison group for the analysis of before-after results [16], regarding the educational program (EP) among people with T2DM, focusing on self-care and in competing physical training (Figure 1).

In a previous study [15], from the same project, the methodological aspects described below were detailed.

Study sample

The base population was made up of people with medical diagnosis of T2DM, regardless of the time of illness, not hospitalized and in outpatient follow-up. The invitation to the study was made in the public health services and by the local media. For the sample selection, the following inclusion/ exclusion criteria were considered [15]:

a) Inclusion criteria: people of both sexes, at least 40 years of age, sedentary or not active, without advanced complications, whose drug treatment included the use of oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) and / or insulin, and who were able to maintain dialogue.

b) Exclusion criteria: people with T2DM who had at least one of the following conditions were excluded: on hemodialysis, amaurosis, presence of sequelae of stroke, cardiac insufficiency, previous amputations at any level of the lower limb, injury or ulcer active in lower limbs, presence of any other incapacitating complication; use of wheelchair and / or stretcher; inability to communicate verbal; and participants in a physical training program at another institution.

Thus, the sample was initially composed of 19 people with T2DM who met the inclusion criteria and volunteered at the study location. After consulting the objectives and procedures of the study, including the need for a medical certificate for the practice of physical exercises, the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF) was provided for reading and signing. However, four participants dropped out due to lack of interest and / or time to attend physical training sessions.

Data collection

After the signing of the FICF, sociodemographic, clinical and medication data were collected in a private room, in the form of an individual interview, with an average time of 30 minutes [15].

The HR was obtained by means of the Polar FT01®, with three components (reader, elastic band and watch), keeping the participants in the orthostatic position during the examination. The SBP and the DBP were measured with aneroid sphygmomanometer (Premium®), previously calibrated by the National Institute of Metrology, Quality and Technology of Brazil (InMetro) and stethoscope (Premium Rappaport®), using a technique standardized by the 7th Brazilian Arterial Hypertension Guideline [17].

All measurements were recorded on the individual physical training sheets, before and after the first one (T0) and before and after the last exercise session (T4).

Interventions

The EP was developed individually in a private room in the premises of the study area, by scheduling in common agreement and through nursing consultations, with a properly trained professional. The frequency of the meetings was in accordance with the individual needs of each participant regarding the topics addressed, conducted face-to-face and dialogically, in a collaborative approach, with an average duration of 50 minutes and maximum periodicity of 30 days.

Illustrative posters, prepared by the researchers themselves, were used containing public domain images related to general disease management and self-care. The educational material was based on the literature and included the following topics: description of the disease process and treatment modalities; practice of physical activity integrated with lifestyle; glucose monitoring and interpretation; control of body weight; appropriate use of medicines; and prevention of complications.

The EP also included 28 sessions of physical training for which the methodology of concurrent training, characterized by aerobic physical exercises in combination with anaerobic or resisted physical exercises was adopted. The aerobic exercises consisted of three weekly sessions of elliptic, treadmill and bicycle, lasting 30 minutes. The resisted exercises were applied to the upper and lower limbs, with three sets of 12 repetitions, also in three weekly sessions with 30 minutes duration.

All exercise sessions were held in a fully equipped gym, in the premises of the study, and under the direct supervision of physical education professionals. It should be noted that the individual educational meetings took place in parallel with the concurrent physical training sessions which were developed in small groups of three to five people, during the four-month period [15].

Statistical analysis

The data collected was double typed in the MS-Excel application and then processed electronically for validation. Subsequently, the data sheet was exported to the GraphPad InStat software, version 3.10 (public domain). The sociodemographic, clinical and treatment variables were submitted to the descriptive statistics for the characterization of the sample. Numerical data on cardiovascular parameters were submitted to the Komolgorow- Smirnov and Levene tests to verify, respectively, the normal distribution and homogeneity of the variances.

For the comparisons between two dependent samples (evaluation before and after the development of EP with physical training), the t-paired test was used, since the normal distribution was evidenced. The results were expressed as mean and standard deviation, with a level of significance (p) of less than 0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic, clinical and treatment characterization of the sample

It was observed that the sample studied consisted of 73.3% of female subjects; mean age of 63 years (standard deviation ̶ SD = 7); mean schooling time of 5.8 years (SD = 5.6); mean time of diagnosis of 8.9 years (SD = 7.6); presence of overweight / obesity; use of oral antidiabetics as prescribed medication treatment (86.7%); absence of prior participation in diabetes counseling groups (100%); and sedentary (73.3%). The sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characterization was detailed in a previous study [15].

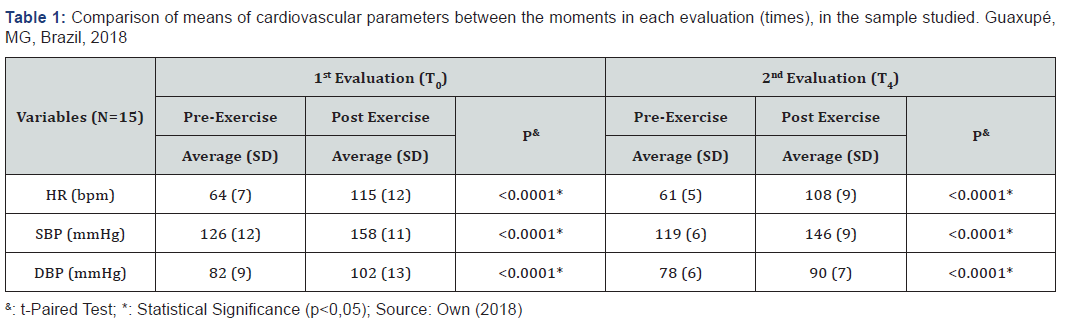

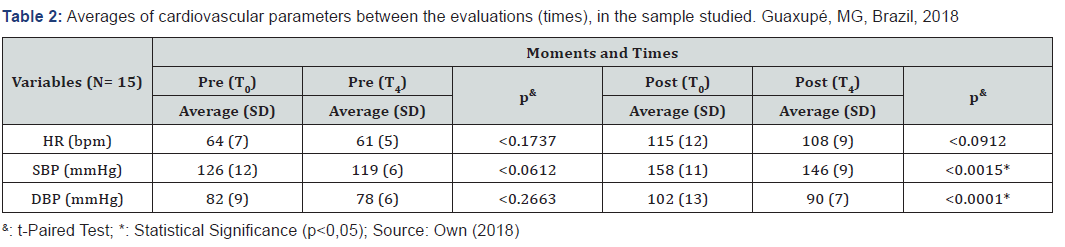

The variables of interest were evaluated in two moments (pre and post) of each study time, that is, in the first session (T0) and in the last session (T4) of physical training. The mean values and standard deviations, and the comparisons between the times (T0 and T4) are shown in Table 1. For HR, there were statistically significant differences between the two moments, in both times. The behavior of SBP was similar to that of DBP, with statistically significant differences between the two moments at both times (Table 1), as well as between the post-T0 moment and the post-T4 moment (Table 2).

Discussion

The sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics were explored and discussed in a previous study, conducted in the same sample studied [15]. In general, these characteristics resemble those of other Brazilian population samples of people with DM [13,18,19].

Concerning the effects of the proposed EP on the HR, there were significant differences between the two moments (pre and post), in both times (T0 and T4). This result is positive, since heart rate variability (HRV) is inversely proportional to the glycemic level. Reduced HRV may indicate impairment of sympathetic and vagal modulation in the heart and is considered a sensitive marker of subclinical autonomic neuropathy [20,21]. This study aimed to evaluate HRV in adults (mean age 51 years) without a diagnosis of DM, but with different degrees of risk for this disease, stratified by the FINDRISC instrument, showed that the high-risk group presented a lower HRV [21]. In the sample studied, because they were elderly individuals, a lower HRV was expected, and the result found reiterates the positive effects of the EP, which included concurrent physical training.

In a previous study [15], that aimed to evaluate the effects of this same EP on glycemic control, a significant reduction of capillary glycemia was observed at the end of the four-month intervention period, suggesting that the glycemic control reach contributed to maintain HRV. Therefore, it is believed that HRV has resulted directly from the regular and well-guided practice of concurrent physical exercise and, indirectly, from face-toface educational meetings, in a collaborative approach and in accordance with the individual needs of each participant. Both interventions contributed to improved glycemic control and, consequently, to HRV.

On the other hand, the absence of statistically significant differences between the pre-T0 and pre-T4 moments, as well as between post-T0 and post-T4, can be explained by the small sample size and short intervention time (four months). An experimental study that trained female and Sprague-Dawley rats for 12 weeks, one hour a day, five days a week, four minutes at 85% - 90% VO2 max. and two minutes at 50% VO2 max., aimed to evaluate the mechanisms underlying training-induced bradycardia. Autonomic block and immunohistochemistry were performed to evaluate HCN4 ion channels as a method for the analysis of pre and post training HR behavior.

Through these channels, the If current is involved in the generation and modulation of the rhythmicity of the heart, and its presence is more intense in the sinus node. The authors concluded that the HR and HRV reduction observed did not result from the autonomic block, but from the blockade of the HCN4 channels, which are responsible for the intrinsic activity of the heart [22]. It is important to note that this experimental training was of high intensity, unlike the one performed in the present investigation, which could also explain the absence of post-training bradycardia in our participants.

Moreover, the scarcity of studies in Brazilian population samples of people with DM, who included physical exercise in educational programs and evaluated the cardiovascular parameters, especially HR, made it difficult to discuss these findings.

Regarding blood pressure (BP), the mean values of SBP and DBP (p <0.0001) were observed, at the post-session moments at both study times (T0 and T4) and, similarly, between the moment after T0 and the moment after T4, suggesting, respectively, improvement in ventricular force and in the capacity of peripheral vasodilation. This result is also positive considering that DM and systemic arterial hypertension are frequently associated conditions [7] and corroborates a recent systematic review on educational interventions in DM, which showed that patientcentered and culturally adapted interventions achieved a slight improvement in pressure [23].

Similar to the present study, a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the contribution of family social support in the clinical / metabolic control of a Brazilian sample of diabetic adults participating in an educational program did not identify significant differences in mean BP values between the groups; however, in the comparison between study times, both groups presented a reduction in BP, with a greater difference for DBP in the intervention group, although without statistical significance [24].

The BP control fits into one of the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) self-care behavioral patterns (“reduce risks”) to guide people-centered educational interventions [25] and, for this reason, of the topics covered in the EP of this research. Although adherence to drug treatment has not been evaluated, it is likely that the guidelines provided in the educational sessions have provided a better understanding and stimulated the appropriate use of medications, including those related to BP control, which may also have contributed to these outcomes.

The current guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Diabetes [7] recommend that, in people with diabetes who are older than or equal to 60 years of age, blood pressure should be maintained at levels not exceeding 150/90 mmHg (grade of recommendation: A) [7]. From the clinical point of view, pressure levels were observed within the established limits. These findings suggest that the educational modality adopted (individual), of short duration and based on the dialogical relationship, allowed a closer contact between professionals and participants, which may have strengthened their sense of autonomy and empowerment [26], resulting in benefits for the blood pressure control of this group.

The proposed EP also provided the regular and guided practice of physical exercises in 28 concurrent training sessions, which seems to have contributed, more significantly, to BP reduction. The literature establishes that physical exercise induces physiological adaptations that lead to pressure control. Concurrent physical training contributes to the increase in cardiorespiratory capacity, muscle strength and endurance, which are necessary for the performance of daily life activities and, therefore, for a better quality of life [27-28].

An intervention study that corroborates the findings of the present investigation, although it employed a different training modality, was developed in 13 weeks to verify the effects of aerobic training in BP, body mass index (BMI) and capillary glycemia of 22 Brazilian women, (G1: control group, n = 11: educational guidelines, once a week, and G2: intervention group, n = 11: aerobic exercises, three times a week). There were no significant differences in blood pressure levels between the groups, but in the comparison of baseline and final values in each group, both showed a significant improvement in BP, especially DBP (p <0.001) [29].

Another important aspect to be considered is that the sample studied was composed of people who were previously sedentary or not very active, and mostly elderly. Studies have shown that advancing age, along with possible physical limitations [30], as well as the lack of appropriate places and / or financial resources for professional follow-up are barriers to physical exercise [31]. In the present study, participants had free access to the equipment and direct supervision of physical educators, as well as the possibility of coexistence with peers in small groups. This appears to have been a motivational factor for most participants to stay in the study. A qualitative research, carried out among elderly women in Florianópolis-SC, Brazil, on barriers and facilitators for physical activity, showed that physical exercises appropriate to the clinical conditions and perception of their benefits in terms of health and quality of life , as well as the company of the pairs and the professional accompaniment, were fundamental for the adherence to this behavior of self-care [30].

As limitations of this investigation, the small sample size and the shortage of studies that used the same modality of EP in Brazilian population samples with DM, and the cardiovascular parameters were evaluated, which made it difficult to compare and expand the discussion of the results.

Conclusion

It is concluded that the proposed EP, by providing guidance on self-care and regular and well-guided practice of concurrent physical training, contributed to changes in lifestyle, understanding of the disease process, and pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment, resulting in cardiovascular health benefits of the sample studied. These benefits were evidenced by the significant improvement of HRV, SBP and DBP, since the same physical effort resulted in lower cardiac stress, as it induced cardiovascular and muscular physiological adaptations. It is suggested that other studies, with different designs and larger sample size, be performed in order to obtain more evidence about the educational practices in DM, since there is still no “gold standard” of EP.

References

- Duncan BB, Chor D, Aquino EML, Bensenor IM, Mill JG, et al. (2012) Chronic non-communicable diseases in Brazil: priorities for disease management and research. Rev Saúde Pública 46(1): 126-134.

- Malta DC, Stopa SR, Szwarcwald CL, Gomes NL, Silva Júnior JB, et al. (2015) Surveillance and monitoring of major chronic diseases in Brazil. National Health Survey, 2013. Rev Bras Epidemiol 18(2): 3-16.

- Felisbino-Mendes MS, Jansen AK, Gomes CS, Velásquez-Meléndez G (2014) Cardiovascular risk factor assessment in a rural Brazilian population. Cad Saúde Pública 30(6): 1183-1194.

- Selvin E, Marinopoulos S, Berkenblit G, Rami T, Brancati FL, et al. (2004) Meta-analysis: glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 141(6): 421-431.

- Siqueira AFA, Almeida-Pititto B, Ferreira SRG (2007) Cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus: classical and non-classical risk factors. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab 51(2): 257-267.

- Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, et al. (2016) European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice : The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 37(29): 2315-2381.

- (2017) Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes 2017-2018. Editora Clannad, São Paulo, Brasil, pp. 383.

- Flor LS, Campos MR (2017) The prevalence of diabetes mellitus and its associated factors in the Brazilian adult population: evidence from a population-based survey. Rev Bras Epidemiol 20(1): 16-29.

- Costa AF, Flor LS, Campos MR, Oliveira AF, Costa MFS, et al. (2017) Burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública 33(2): 1-14.

- Borges DB, Lacerda JT (2018) Actions aimed at the diabetes mellitus control in primary health care: a proposal of evaluative model. Saúde Debate 42(116): 162-178.

- (1998) Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Br Med J 317(12): 703-713.

- Siqueira FV, Nahas MV, Facchini LA, Silveira DS, Piccini RX (2009) Counseling for physical activity as a health education strategy. Cad Saúde Pública 25(1): 203-213.

- Figueira ALG, Gomes-Villas Boas LC, Coelho ACM, Foss-Freitas MC, Pace AE (2017) Educational interventions for knowledge on the disease, treatment adherence and control of diabetes mellitus. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem 20(25): 1-7.

- Ji H, Chen R, Huang Y, Li W, Shi C, et al. (2018) Effect of simulation education and case management on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res 35(3): 1-7.

- Silva Júnior AJ, Gomes LC (2019) Effects of an educational program focused on self-care and concurrent physical training on glycemia and drug treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Updates 5: 1-7.

- Polit DF, Beck CT (2011) Fundamentos de pesquisa em enfermagem: avaliação de evidências para a prática da enfermagem (7th edn). Artmed, Porto Alegre, Brasil.

- Malachias MVB, Souza WKSB, Plavnik FL, Rodrigues CIS, Brandão AA, Neves MFT (2016) 7ª Diretriz Brasileira de Hipertensão Arterial. Arq bras cardiol 107(3): 1-83.

- Cortez DN, Santos JC, Macedo MML, Souza DAS, Reis IA, Torres HC (2018) Effects of an educational program on self-care empowerment for the fulfillment of goals in diabetes. Cienc Enferm 24(1): 23-32.

- Gomes LC, Silva Júnior AJ (2018) Factors favorable to diabetic foot in users of a primary health care unit. Rev Aten Saúde 16(57): 5-12.

- Stein PK, Barzilay JI, Domitrovich PP, Chaves PM, Gottdiener JS, et al. (2007) The relationship of heart rate and heart rate variability to non-diabetic fasting glucose levels and the metabolic syndrome: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabet Med 24(8): 855-863.

- Silva-e-Oliveira J, Amélio PM, Abranches IL, Damasceno DD, Furtado F (2017) Heart rate variability based on risk stratification for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Einstein 15(2): 141-147.

- D'Souza A, Bucchi A, Johnsen AB, Logantha SJ, Monfredi O, et al. (2014) Exercise training reduces resting heart rate via downregulation of the funny channel HCN4. Nat Commun 13(5): 1-12.

- Bhurji N, Javer J, Gasevic D, Khan NA (2016) Improving management of type 2 diabetes in south Asian patients: a systematic review of intervention studies. BMJ Open 6(4): 1-16.

- Gomes LC, Coelho ACM, Gomides DS, Foss-Freitas MC, Foss MC, et al. (2017) Contribution of family social support to the metabolic control of people with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Appl Nurs Res 36: 68-76.

- (2008) AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors. American Association of Diabetes Educators. Diabetes Educ 34(3): 445-449.

- Mendes GF, Rezende ALG, Dullius J, Nogueira JAD (2017) Adherence barriers and facilitators to a diabetes education program: the user’s point of view. RBAFS 22(3): 278-289.

- Tokmakidis SP, Zois CE, Volaklis KA, Kotsa K, Touvra AM (2004) The effects of a combined strength and aerobic exercise program on glucose control and insulin action in women with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Appl Physiol 92(4-5): 437-442.

- Arsa G, Lima L, Almeida SS, Moreira SR, Campbell CSG, Simões HG (2009) Type 2 diabetes mellitus: physiological and genetic aspects and the use of physical exercise for diabetes control. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 11(1): 103-111.

- Monteiro LZ, Fiani CRV, Foss-Freitas MC, Zanetti ML, Foss MC (2010) Decrease in blood pressure, body mass index and glycemia after aerobic training in elderly women with type 2 diabetes. Arq Bras Cardiol 95(5): 563-570.

- Krug RR, Lopes MA, Mazo GZ (2015) Barriers and facilitators for the practice of physical activity in old and physically inactive women. Rev Bras Med Esporte 21(1): 57-64.

- Bonetti É, Schaly D, Rover C, Fiedler MM (2012) Atividade física em indivíduos portadores de diabetes mellitus do município de Joaçaba, SC. Evidência 12(1): 41-50.