Bridging Allure with Importunity of Medical Tourism

Ramalingam Shanmugam*

Honorary Professor of International Studies, School of Health AdministrationTexas State University, USA

Submission: April 13, 2018; Published: July 17, 2018

*Corresponding author: Ramalingam Shanmugam, Honorary Professor of International Studies, School of Health Administration Texas State University, San Marcos, TX 78666, USA; Email: rs25@txstate.edu

How to cite this article: Ramalingam S. Bridging Allure with Importunity of Medical Tourism. Biostat Biometrics Open Acc J. 2018; 7(5): 555724. DOI: 10.19080/BBOAJ.2018.07.555724

Summary

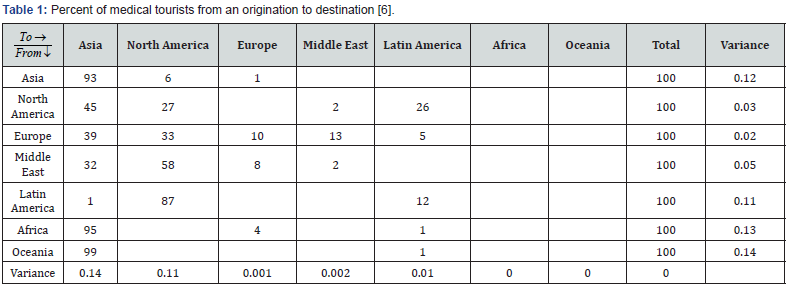

The advancement in medical facility and lesser cost of treatment are understandably de facto in medical tourism between originating and destination continents. However, data about facility or full details about cost are not usually available and hence, are not involved in discussions of medical tourism. Hence, in this article, an innovative visual approach based on probability and statistical concepts is adapted to capture and comprehend on how alluring patients in an originating continent are bridged to importunity in a destination continent in the practices of medical tourism. Both the concept and method are illustrated using the data in Table 1.

Keywords: Probability; Stochastic independence; Radar network visual; Proximity angle; Medical facility; Statistical concepts; Globalization; Decontrolling regulations; Private equity funds; Medical brokerages; Patient’s affordability; Medical treatments; Cornea and retina; Hysterectomy; Liposuction; Ivy treatments; Lasik eye-surgery; Symmetry; Non-within continents; Random numbers; Variance stability; Obtuse angle

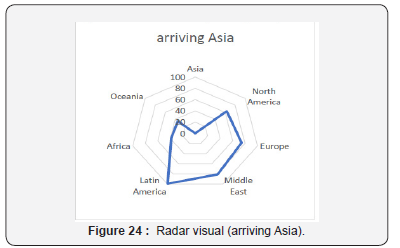

Abbrevations: AF: Africa; AS: Asia; EU: Europe; LA: Latin America; ME: Middle East; NA: North America; OC: Oceania; GDP: Gross Domestic Product

Introduction

Of course, advantages as much as risks exist in the practice of medical tourism. Patients in an originating continent chose to visit medical facility in a destination continent for a treatment and this process is recognized as medical tourism. In 21st century, medical advancements have become reality in several continents due to the globalization. Some de facto in the medical tourism are affordable cost and/or advanced medical facility. A lack of authentic pertinent information associated with such facto cripples its usage in the discussion of popularity of a specific continent for medical tourists. How should an analyst proceed to capture and illustrate the attractiveness (or rather importunity) of a destination continent among the alluring patients in an originating continent? This question is the research theme of this article. For discussions in this article, Africa (AF), Asia (AS), Europe (EU), Latin America (LA), Middle East (ME), North America (NA), and Oceania (OC) are considered.

Analysts wonder on how the above mentioned seven continents compare with respect to each other in so far as outbound versus inbound medical tourist flows. In other words, do medical tourists in one originating continent are spanned off at a rate to destination continents in comparison to a different rate in opposite direction. Likewise, the attraction rate of medical tourists in a destination continent differs for an originating continent to others. Could we construct radar network type visuals to assess their adjacency? A picture is worth thousand words in any discussion including the medical tourism in this article.

Of course, in medical tourism, the demand and supply of healthcare facilities are influenced by the social or economic living conditions in the continents. However, the healthcare is a significant part of every country’s economy in the continent. In 2011, the healthcare industry consumed a 9.3 percent of the US gross domestic product (GDP), a 10 percent of the Canada’s GDP, and about 11 percent of the France’s and Germany’s GDP. Healthcare reforms are discussed not only in the developed but also in the developing continents. Private as well as public insurance institutions in almost all continents engage in decontrolling regulations for their patients to seek and obtain best affordable medical service from where ever they could for the sake of minimizing the healthcare cost.

Turner reported that India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and many others promoted them as favorable countries for medical tourism [1]. These countries coupled their national airlines, hotel chains, investors and private equity funds, and medical brokerages with the medical tourism. They attracted uninsured Americans and other overseas patients who were unable to afford health care in their home countries. In specific, Turner argued that there were increasing numbers of patients leaving their home countries in search of orthopedic surgery, ophthalmologic care, dental surgery, cardiac surgery and other medical interventions. Cohen [2] critically assessed the social consequences of medical tourism, He claimed that the western medical tourists out pouring to those hubs in eastern continents primarily for cosmetic or other elective treatments.

Shanmugam [3] mentioned that the globalization in this 21st century unified nations. to promote trade in the medical profession for the patient’s affordability [3]. The medical tourism created an economic turmoil. Several medical economists were quite puzzled by the advantages as much as by the damaging impacts by the booming popularity of the medical tourism. Using the principal component analysis, Shanmugam formulated three groups of nations in medical tourism.The first group consisted of USA, Columbia, Costa Rica and Nicaragua. The second group consisted of India, Israel and South Africa. The third group consisted of Jordan, Thailand and Malaysia. Based on the cost of the medical treatment, he articulated that there were three types of medical treatments in the medical tourism.The first type consisted of heart by-pass, angioplasty, heart valve replacement, hip replacement, hip resurfacing, knee replacement, spinal fusion, gastric sleeve and gastric by-pass and lap band and liposuction and ivy treatments. The second group consisted of tummy tuck, breast implants, rhinoplasty, facelift, hysterectomy, cornea and retina. The third group consisted of dental implant and Lasik eye-surgery.

Izadi et al. [4] asserted that like any other rapidly growing industry, the medical tourism prompted ethical and legal issues. These issues pertained to malpractice or consumer protection. Moreover, the risk management, foreign hospital liabilities, facility ownership, intellectual property, organ trafficking and ethical issues became concerns. Travel medicine got confused with alternative medicine and telemedicine. Therefore, comprehensive and detailed legal regulations became necessity to control the issues. Many nations in the continents legislated laws for the medical tourism. Despite the improvements, the future the medical tourism industry still faces serious challenges.

To construct such visuals, we utilize probability syllogisms concepts and mosaic masonries of Shanmugam [5]. Some syllogistic reasonings ought to assist for a better understanding of mysterious medical tourism. In other words, our research aim should be about devising statistical concepts (like correlation type results with related angles) and appropriate analytical tools in a novel manner, to construct visuals between the originating and destination continents in the medical tourism.The concepts and tools are developed in Section 2 and are illustrated in Section3, using the data in Ehrbeck et al. [6]. Finally, in Section 4, comments and conclusions are made for further research work to advance the line of thinking for further comprehension for nifty gritty implications of the medical tourism.

Data analytics for medical tourism

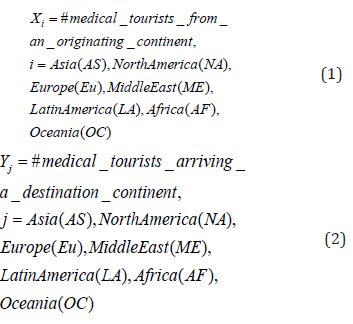

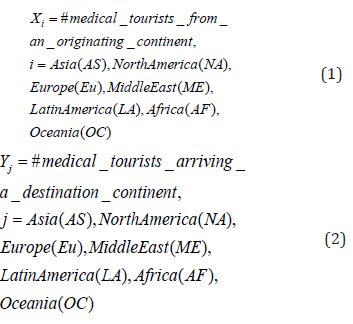

First in this section, for the sake of easy comprehension, we introduce and explain several notations and abbreviations.

Notations:

Conditional probability:

The entries in Table 1 are the proportions Prij of the medical tourists from an origination i to a destination j among the seven continents. For an example, when iNA= (north America) andjAS= (Asia), the proportion is Prij=0.45≠Prij where Prji=0.06 The exchanges between two are not of the same proportions, causing an imbalance in this medical tourism trade off.Understandably, the conditional mean (Yj|Xi)=1/n where n denotes the number of continents. The conditional expectation remains constant. But, their conditional variances var(Yj|Xi) vary among the continents. On the contrary, both the conditional mean E(Xi|Yj) and the conditional variance var(Xi|Yj) of the inflows vary among the destination continents.

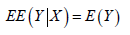

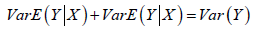

In such a scenario of medical tourists, let us designate that X= total potential number of medical tourists leaving all the destinations and Y= the total potential number of medical tourists arriving all the destinations. From the statistical theory, we realize that EE(X|Y)|=EX and varE(X|Y)+Var(X|Y)=Var(X) the unconditional variance, which is useful to interpret the stability of the outbound random number of medical tourists, .X Likewise, the results

And

portray the unconditional mean and stability of the inbound random number of medical tourists, .Y

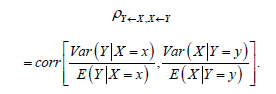

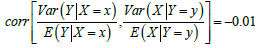

We now introduce the reverse-cross correlation to capture the symmetry in the overall movements among the continents and it is

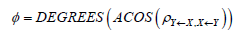

When the correlation ρY←X,X←Y=0, it is to be interpreted as the outbound flow from the continents in the collection ℬ to continents to the continents in the collection ℋ is unconnected to the reverse inflow from the continents in the collection ℋ to the continents in the collection ℬ. If the correlation ρY←X,X←Y<0 it is to be regarded as the outbound flow from the continents in the collection ℬ to continents in the collection ℋ is reduced by the reverse inflow from the continents in the collection ℋ to the continents in the collection ℬ. On the contrary, if the correlation ρY←X,X←Y>0 it is to be regarded as the outbound flow from the continents in the collection ℬ to continents in the collection ℋ is increased to the reverse inflow from the continents in the collection ℋ to the continents in the collection ℬ. The corresponding impact angle of the correlation ρY←X,X←Y=0 is

in its domain[0,360]o. Then, we could then define the ratios: ℜ=E(X)/E(Y) to capture the total expected numbers of medical tourists leaving to the arriving. Likewise, the ratio ℑ=Var(X)/Var(Y) portrays the stability of those leaving to arriving in the system of medical tourism. We now proceed to explore further to formulate visuals.

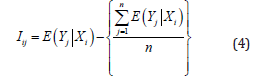

Shanmugam [7] developed, discussed, and then integrated syllogisms in conditional probability settings to identify the “better” features of “Youden’s” diagnostic testing methods. His method was based on the sensitivity and specificity measures. His syllogisms utilized what was named “double anchored” relationship. A principle of authentication was established to indicate the favorable or dis-favorable evidence level in the diagnostic data. Also explained was whether parity existed between the two reciprocal evidences. Such a parity level distinguished a strong from a circumstantial evidence. Following Shanmugam’s line of thinking in the conditional mean and variance setting, we compute

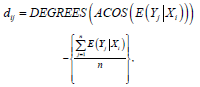

as a measure of medical tourism intensity between the origination continent Xi and the destination continent .Yj Notice that the intensities fall in the domain [-1,1] like the correlation measures. Hence, we translate the intensity into an appropriate degree in the domain [0,360]oo as an anti-clockwise direction for an origination continent to a destination continent using

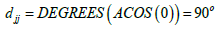

to capture their adjacency between two continents in the medical tourism. When the intensity level is 0,ijI= then their proximity in the medical tourism is dij=90o meaning an orthogonal adjacency (that is, a statistically independency).If the intensity level is Iij<0 then there exists a lesser statistical adjacency between two continents in the medical tourism with ij>90o (an obtuse angle). On the contrary, with the intensity level is Iij>0 then the statistical adjacency between two continents in the medical tourism is indicative of more attractiveness with dij<90o<(an acute angle). We summarize it a theorem below.

Theorem 1

The statistical adjacency between originating and destination continents in the medical tourism is

Where Yj and Xi denote respectively the random numbers of arriving the jthdestination and leaving the thi originating among n number of continents with 1,2,..,n

Those medical tourists travelling within a continent from a country to another do not excite research enthusiasm as much as those go outside the continent. In this sense, why not analyze the data after excluding the “within continent” travelling in medical tourism. This amounts to removing diagonal entries in the Table 1 from the analysis. Then, the concepts stay the same, but the expressions change. That is, the corresponding ratio ℜ*=EnonDiagonal(X)/EnonDiagonal(Y) captures the expected number of medical tourists leaving versus arriving under the exclusion of medical tourists within the continent. Likewise, the ratio ℑ*=VarnonDiagonal(X)/VarnonDiagonal(Y) portrays the stability of the leaving versus arriving in the system of medical tourism under the exclusion of medical tourists within the continent. Notice that 0jjI= is the intensity measure in the medical tourism if the origination and destination continents are the same.

Their statistical adjacency within the continent is

for such continents in the medical tourism. Because of this diagonal restriction, other statistical adjacencies do change with “non-within continents”. Appropriately, the theorem 1 changes to theorem 2.

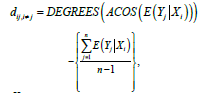

Theorem 2

The statistical adjacency between originating and destination continents in the medical tourism is

Where Yj and Xi denote respectively the random numbers of arriving the jthsup> destination and leaving the thi originating among n-1 number of continents with .i≠j

Illustration

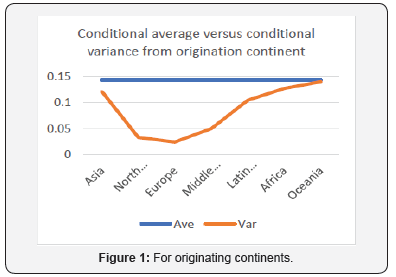

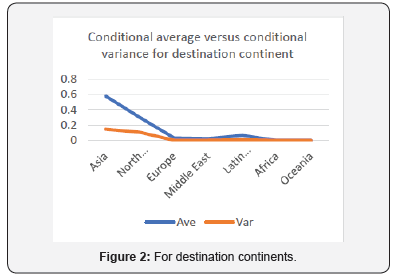

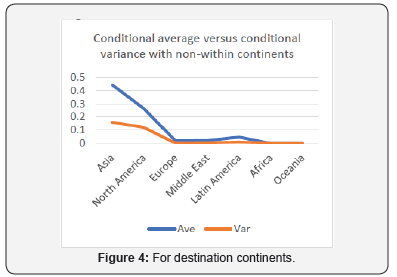

We now proceed to illustrate the concepts and expressions of Section2 with the reported medical tourism data in Table1. Note that this medical tourism data is imbalanced, and it opens a lot more research excitement which will be further explored in this article. The conditional mean E(Yj|Xi) is constant across origination continents with 7n= but their conditional variances Var(Yj|Xi) vary suggesting the number of medical tourists is not stable across the continents (Figure 1 & 2). For the medical tourism data in Table 1, the ratios are ℜ=E(X)/E(Y)=0.142/0.142=1 and ℑ=Var(X)/Var(Y)=0.085/0.085=1 meaning that there exist average and variance stability in the system of medical tourism. Note that the ratio ℜ=EnonWithin(X)/EnonWithin(Y)=0.113/0.113=1 captures the expected number of medical tourists leaving versus arriving under the exclusion of “within continent” medical tourists. Likewise, the ratio ℑ=VarnonWithin(X)/VarnonWithin(Y)=0.071/4.852=0.014 portrays the stability of the leaving versus arriving in the system of medical tourism under the exclusion of medical tourists within the continent. The “non-within continental inbound” flows are not stable.

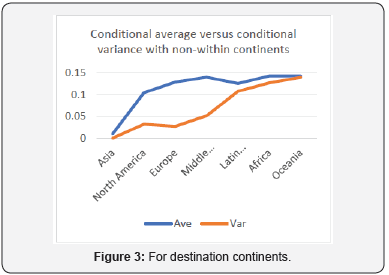

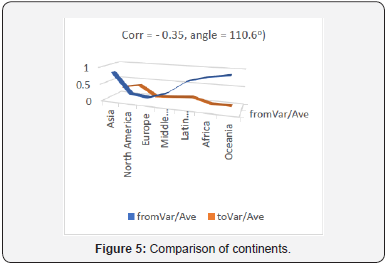

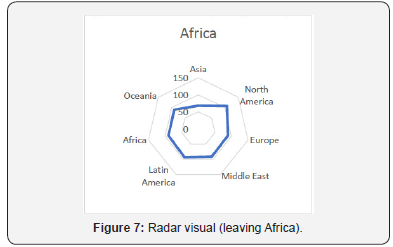

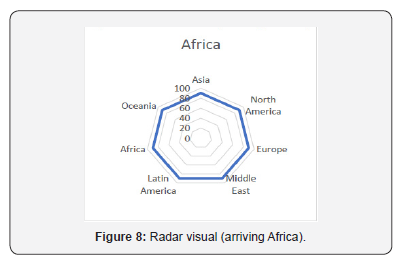

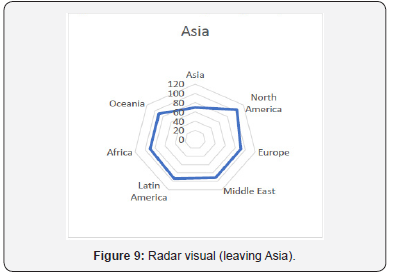

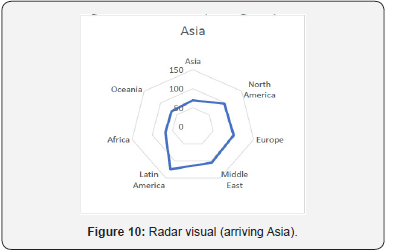

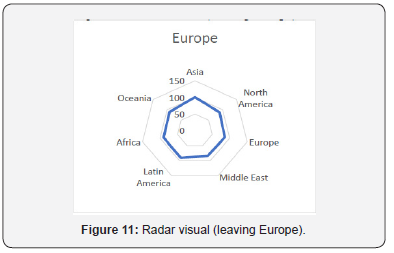

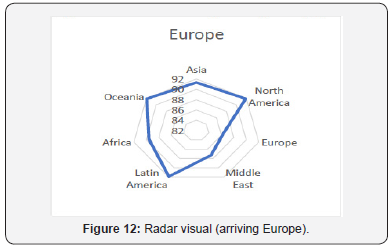

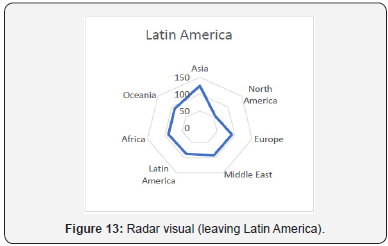

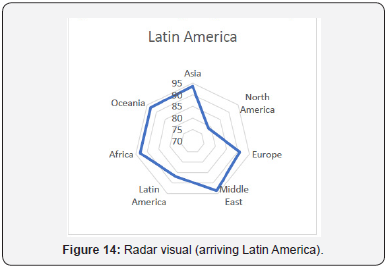

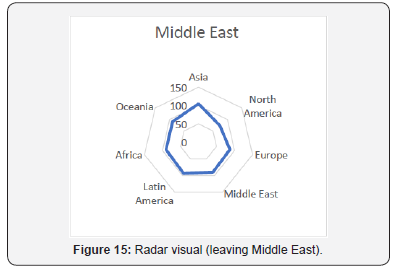

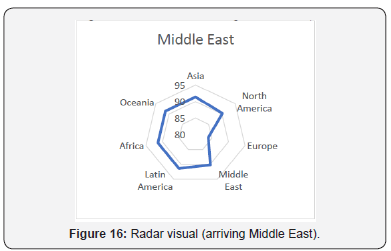

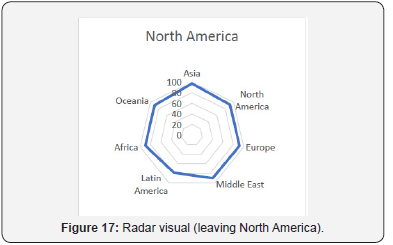

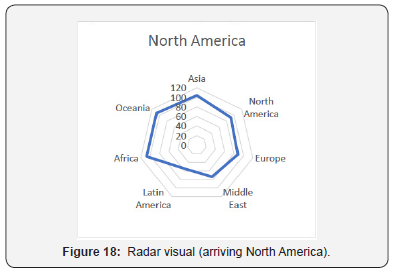

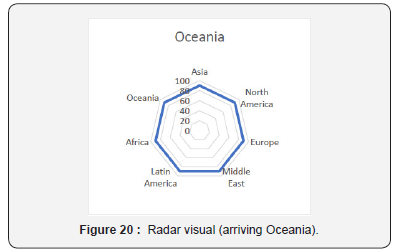

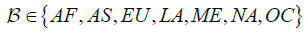

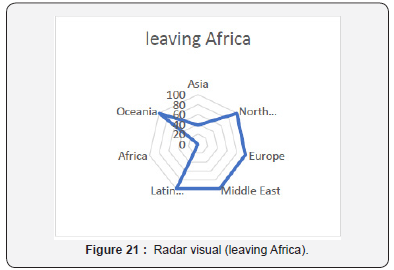

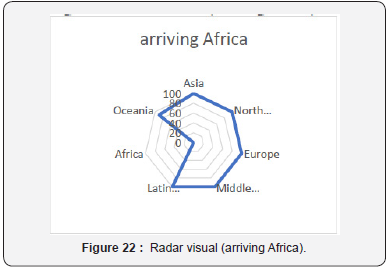

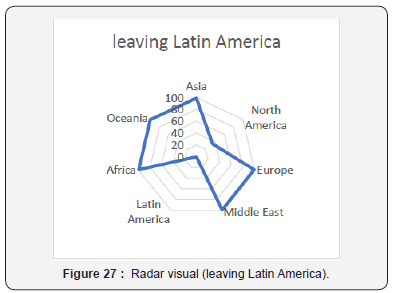

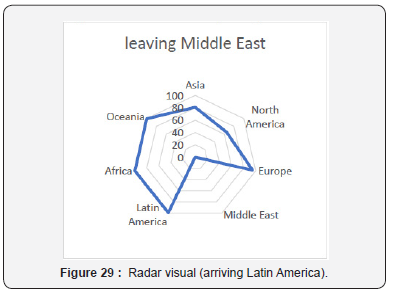

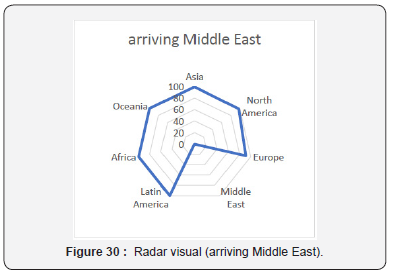

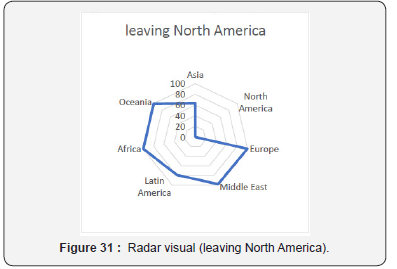

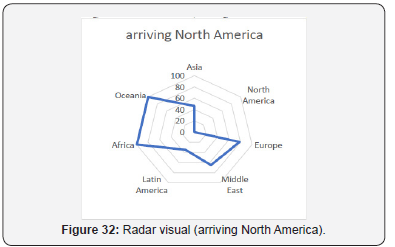

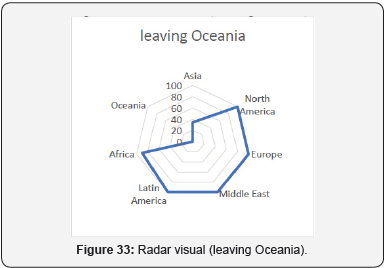

The “non-within continental outbound” flow is stable.Such an instability is indicative of heterogenous continents in so far as the medical facilities. With an exclusion of “within continent tourists”, the patterns of the conditional mean ()jiEYXand the conditional variances Var(Yj|Xi) for origination continents shift significantly suggesting the number of medical tourists is not stable across the continents (Figure 3 & 4). We now compute and interpret the statistical adjacency of the continents in medical tourism. Recall that if the intensity is zero (that is, 0ijI=), then their statistical adjacency in the medical tourism echoes an orthogonal situation (that is, dij=90o) Note that the statistical adjacency between Latin America as an origination continent to Asia as a destination continent consists of intensity level 0.567ijI=− and angel level 124.6oijd= (an obtuse angle) meaning lesser medical tourism. On the contrary, the statistical adjacency between Latin America as an origination continent to North America as a destination continent consists of the intensity level0.569ijI= and the angle level 55.35oijd= an acute angle). An acute proximity angle level is indicative of more frequent medical tourism. Based on the angles, we construct and display radar visuals for leaving and arriving medical tourists in continents AF, AS, EU, LA, ME, NA, and OC (Figures 5-20).

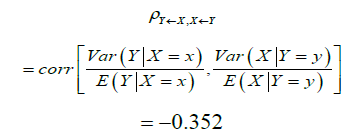

The reverse-cross correlation to capture the symmetry in the overall movements between the continents and it is

It means that the outbound flow from the continents in the collection

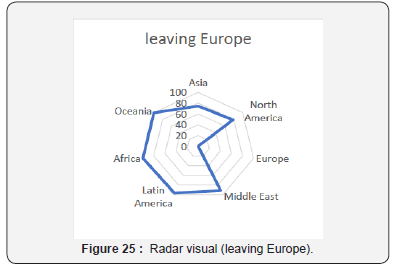

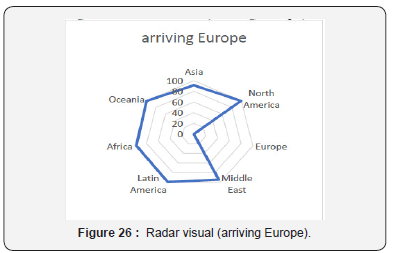

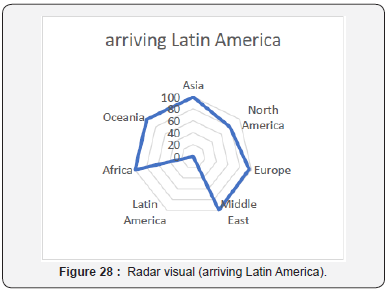

to continents in the collection ℋ is reduced by the reverse inflow from the continents in the collection ℋ to the continents in the collection ℬ. The corresponding impact angle is 110.6o and it indicates a non-orthogonality (non-independency) between the leaving and arriving of medical tourists). Next, we examine the impact of excluding the “within continent” in the medical tourism from the analysis to check whether it causes deviations the statistical adjacency of the continents in medical tourism. Based on the calculated new angles, we construct and visualize the changes in the radar visuals for leaving and arriving medical tourists in continents AF, AS, EU, LA, ME, NA, and OC (Figure 21-34).

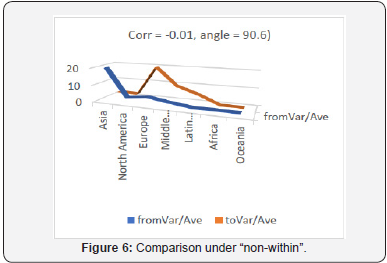

We note that

It means that the outbound flow from the continents in the collection ∈{AF,AS,EU,LA,ME,NA,OC) to the continents in the collection ℋ is slightly reduced by the reverse inflow from the continents in the collection ℋ to the continents in the collection ℬ. The corresponding impact angle is 90.6o and it indicates a slight orthogonality. It suggests that the exclusion of “within medical tourists” changes dramatically the visual impression (compare Figures 7-20 with their corresponding Figures 21 through 34) and the understanding. The analysts ought to analyze the entire medical tourism data without the exclusion of “within medical tourists”.

Comments and Conclusion

This article devised both the statistical concepts and analytical tools to check whether the number of medical tourists leaving a continent is independent of arriving number in the seven continents. Expressions are derived to compute their correlation and the angular impact. Also constructed and demonstrated are the visuals for the medical tourism data. These contributions help the analysts to interpret the meaning and implications of the medical tourism patterns over the years. For a variety of reasons [8], the patterns could shift. Such identified shifts become the basis for a trial to understand the consequences of healthcare policies or regulations.

Acknowledgement

The author appreciates and thanks an anonymous referee for valuable suggestions which helped to improve contents and quality of the article

References

- Turner L (2007) First world health care at third word prices: Globalization, bioethics and medical tourism. BioSocieties 2: 303-325.

- Cohen E (2010) Medical travel-a critical assessment. Tourism Recreation 35(3): 225-237.

- Shanmugam R (2012) Booming medical tourism and economic indices. International Journal of Research in Nursing 3(2): 38-47.

- Izadi M, Ayoubian A, Saadat S, Zarnaq RK, Abbasi S, et al. (2013) Medical travel: Ethical and legal challenges. International Journal of Travel Medicine and Global Health 1(1): 23-28.

- Shanmugam R (2008) Double anchored syllogisms for medical scenarios. J Stat & Appl 3(2): 255-278.

- Ehrbeck T, Guevara C, Mango PD (2008) Mapping the market for medical travel. The McKinsey Quarterly, Healthcare 2: 1-12.

- Shanmugam R (2009) A tutorial about diagnostic methodology with dementia data. Int J Data Analysis Techniques and Strategies1(4): 385-406.

- Ha H, Ham S, Kim Y (2012) Medical hotels in the growing healthcare business industry: impact of international travelers perceived outcomes. Paper Presented at the Global Marketing International Conference, Seoul, Pp. 1844.