Required Institutions in Economic Development

Solomon I. Cohen*

Professor of Economics, Erasmus School of Economics, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands

Submission: March 03, 2024; Published: March 12, 2024

*Corresponding author: Solomon I. Cohen, Professor of Economics, Erasmus School of Economics, Rotterdam, Netherlands. E-mail: cohen@ese.eur.nl.

How to cite this article:Solomon I. C. Required Institutions in Economic Development. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2024; 10(1): 555778. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2024.10.555778

Introduction

Institutions refer to the formal and informal rules, norms, and practices that shape economic behavior and decision-making in a society. Institutions can be viewed as the roots on which society grows. The way the roots are bent so the tree will grow. The role of institutions in shaping and determining the pace of economic development has been a central topic in economic literature. Various contributions have examined how different institutions, such as property rights, political systems, and the rule of law, shape economic outcomes. The contributions offer insights into the challenges and opportunities for upgrading institutions to the levels required for promoting economic growth and development. North [1] examined the role of institutions in economic development from a historical perspective. Amendola et al. [2] examined the impact of institutions on income distribution from an empirical perspective. Acemoglu and Robinson [3] and Bardhan [4] emphasized the political economy of institutions.

There are subtle differences when the above contributions are compared with our approach which this paper highlights. Some countries (developing or developed) are more fortunate to have institutions that promote the development process, but there are some countries that are stuck with institutions that hinder speedy development. It follows that for these less fortunate countries, the positive impacts of development policies are significantly reduced, irrespective of how well intended, well designed, and well implemented these development policies are. Institutional management is crucial, though while some institutions are controllable, many institutions are sticky and do not adjust easily.

The questions we raise are: Which types of institutions are there? What are their origins? To what extent can be redesigned so as to promote development? This paper will take a glimpse on these questions, while a fuller treatment is addressed in Cohen [5].

Institutions can be categorized into two types based on their origin and maintenance: system institutions and outer institutions. System institutions are created by the economy-polity system, they are formal, legalized and sanctioned; can be changed, are controllable and adjustable. Outer institutions are historically and intergenerationally acquired and are created and maintained in the context of socio-cultural communal discourses in the nation as a whole. They are culturally cultivated attitudinal values that are manifested in common practices that related agents generally adhere to. They are informal , conventional, more enduring and less adjustable. The outer institutions circumscribe the system institutions.

System theory and system institutions

System theory explains how agents interact in subsystems (i.e. households, firms, government, military, judiciary, religion etc.) and how these subsystems build up institutions to guard their interests and prevalence. As a result of agent mobility , economic transitions, technological developments and political events, there are inherent tendencies for one subsystem to dominate the other subsystems, resulting in a hierarchy of dominant institutions. By way of an example, system theory reasons that in the US, the high concentration of agent and transactions in firms has allowed over time the subsystem of firms with their goal of profit maximization and institutions backing this goal to dominate the whole system. Similarly, it can be reasoned that different initial conditions and developments led to the dominance of the state subsystem in Soviet Russia, and even though the Soviet regime is gone the state subsystem with its commandant and rental servicing institutions are still dominant in Russia . There are many developing countries that show a mix of subsystems without as yet one dominant subsystem. For a comprehensive application of system theory to economic systems in the world at large see Cohen [6].

Irrespective of whether the economy polity system is dominated by firms or by the state, for the whole system to survive, expand, and result in more well being for all citizens, the system requires supporting institutions that are effectively sanctioned for ensuring four conditions: (1) Free competition, entry, and exit for firms and government are to be fostered and non-competitive practices are to be minimized. (2) Exchange uncertainties associated with the exchangers and the exchanged goods and services(economic and political) need to be reduced to the minimum. This requires that property rights are legally respected, that agents and principles can be trusted to live up to their contracted promises, fair settling of disputes when they arise, and that near to perfect information exists and flows smoothly between parties concerned i.e. these can be buyers and sellers, or voters and governors. (3) Externalities caused by one party are held in check and are internalized back to the causing party. (4) Factor remuneration: While supply and demand considerations will always influence rewards to the factors of production in the short run, factor rewards should reflect their factor productivities within the firm and across firms in the longer run. The same applies for rewards to the remuneration of state governors.

Since it is impossible for firms and markets to fulfill these four conditions on their own, the state subsystem is called upon to correct and manage the market failures. For interventions by the state subsystem to be optimal, these are equally required to be governed by serving institutions and regulations that are transparent, unbiased, and non-exploitive.

A question which is often raised is whether the pro-firm (market) system is superior to the state led system in terms of creating more welfare for all citizens. The posed question assumes that there is a system that can be labelled as optimal. In principle, because so many countries have many specific differences to which their systems have adjusted, there is no one optimal order that can be labeled as such. It can be defended that each country-specific situation produces its own optimal systemic mix. Notwithstanding, some performance statistics would suggest that countries with relatively more firm dominance than state dominance had better economic performance. China defies the suggested association with its system of firms subordinated to state policy directions, and nevertheless, the country has been able to achieve the highest ever realized economic performance in three decades. The point is that China was successful in creating and maintaining the market institutions and state institutions required for the China system to work. Decades earlier, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong had their own combinations of well-implemented market and state institutions that allowed them to achieve swifter development than their contemporaries. The central question to be addressed is whether the required market institutions and state institutions are present and are well functioning in the investigated country.

Outer Institutions

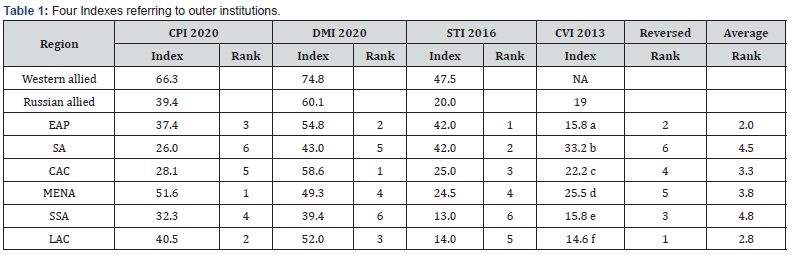

Out of the many outer institutions and their behavioral manifestations, we choose to highlight four behavioral traits that play crucial roles in retarding(promoting) development. These are (1) corruptive practices that distort fair competition, (2) social distrust between transacting agents (due to differential attitudes) that discourages exchange and transactions, (3) societal stratification (feudal system) with a rent-extracting character that discourages agent mobility and efficient allocation of resources, and (4) polarization (due to non-compromising ideologies, belief, ethnicity, or nationalism) that excludes cooperation and in the extreme can lead to warlike conflicts. The four types of institutions can be briefly labelled as corruption, stratification, distrust, and polarization. The objective of this section is not to demonstrate the significant impact of these outer institutions on economic development. This has already done by many and has been proven. There is more need for monitoring and document the lags and successes accomplished in the four areas by country and region, and where feasible to contribute indirectly to identifying and transferring the conditions of success in the successful country to the lagging country, having in mind that progress in the four areas involves long-term socio-cultural changes. Accordingly, we humbly reviews some available indicators on the outer institutions in the development regions in Table 1.

CPI= Corruption Perception Index, From Transparency International CPI 2020. DMI= Destratification Mobility Index. From World Economic Forum 2020. STI= Social Trust Index From World Value Survey 2016. CVI= Civil Violence Index 2017. From Feindouno et al. [7]. Countries with highest scores by region. a. Thailand 38. b Afghanistan 57, Pakistan 64. c. Index for ex soviet Islamic republics approximated at value of Russia, Turkiye. d. Iraq 68, Syria 56, Yemen 58. e. Nigeria 55, Somalia 53, DR Congo 39, Zambia 50. f. Colombia 51

Corruption: The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) by Transparency International (2022) ranks 180 countries and territories around the world by their perceived levels of public sector corruption as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys. The index does not treat corruption in the private sector which can be as extensive as in the public sector. The results for 2020 are given on a scale of 100 (very clean)–0 (highly corrupt). Results in Table 1 reveal that corruption levels are at a worldwide standstill. The global average remains unchanged for the tenth year in a row, at just 43 out of a possible 100 points. Two-thirds of countries score below 50, indicating that they have serious corruption problems. The results for six development regions range between 52 and 26 points and rank as follows from cleanest to corrupt: MENA, LAC, EAP, SSA, CAC, and SA.

Stratified immobility: Social stratification ranks the relative position of a group or persons belonging to a group in the whole population. For example, caste is viewed among the lowest ranks with members of the cast immobile and unable to move upward. In caste systems, all aspects of social status are ascribed such that one’s social position at birth persists throughout one’s lifetime. Development opportunities are missed in this institutional setup. Social mobility is the movement of individuals and social groups between the layers. Mobility can be intragenerational or intergenerational. Countries/societies with high upward intragenerational mobility make use of progressive institutions that promote development. Little mobility retards development. The Global Social Mobility Report produced by the World Economic Forum (2020) includes a Destratification Mobility Index (DMI) that ranks countries in 2020 according to their performance across five key pillars: healthcare, education, technology access, working conditions, and social protection. Western-allied countries score high at 75 points out of 100 points. Within the West, the Scandinavian countries have the top index scores of 83–85 points. If a person is born into a low income family in Denmark, the WEF estimates it would take two generations to reach a median income. In contrast, for someone in India, Egypt, South Africa, or Guatemala (with scores of 40–44 points), it would take nine generations to reach the median at the current pace of growth. The development regions are ranked in from high to low as follows: CAC, EAP, LAC, MENA, SA, and SSA. The low score on mobility in the South Asia region at 43 points reflects the high occurrence of caste and related stratifications in India and neighboring countries.

Social distrust: Levels of social trust in a nation predict national economic growth as powerfully as financial and physical capital. Low trust implies a society where one has to keep an eye over one’s shoulder, which ultimately limits exchange and misses economic opportunities to grow. To assess the relative level of interpersonal trust, the World Values Survey (WVS) asks the following: “Would you say that most people can be trusted?” The percentage of respondents giving a yes answer forms the Social Trust Index (STI). Table 1 shows the Western-aligned countries scoring on average 47% (with Scandinavian countries scoring 66%), compared to Russia at 20%. The development regions vary between values of 42 and 13 ranked in the following order: EAP, SA, CAC, MENA, LAC (14), and SSA (13). It is important to note the low level of social trust in LAC at 14% for a region that is more economically developed than others.

Polarized violence: A Civil Violence Index (CVI) was developed and applied by Feindouno et al. [7]. The index focuses on polarized violence. It is a composite indicator of four clusters: internal armed conflict, criminality, terrorism, and political violence in the forms of political assassinations and riots. They applied the index to Russia and 130 developing countries. We aggregate their results for the six development regions on the basis of simple averages for each region. There is a high country variation by region as can be read from the footnote, sitting countries with the highest index of violence. The results in Table 1 show South Asia (SA), MENA, and SSA having the highest levels of violence which are easily recognized in view of the high figures observed for Afghanistan and Pakistan in SA, and Iraq, Syria, and Yemen in MENA, and Nigeria, DR Congo, Somalia, and Zambia in SSA. Except for Nigeria which is fortunate to have rich natural resources, all the above-mentioned countries are progressing very slowly in terms of economic development.

Concluding remarks

We have so far discussed system institutions and outer institutions in isolation from each other. Although corruption is viewed as an outer institution, there is acknowledged evidence that corruption is associates with the state-led system. But since corruption exists in all systeams, it is rightly identified as an outer institution. The three other areas relate to behavioral manifestations of transmitted and acquired conventions. Their origin and persistence are due to transmitted socio-cultural behavioral patterns at highly differentiated community levels. Nevertheless, there can be situations in which the outer institutions and the system institutions collide and strengthen each other. An ethnically exclusive, self-enriching, or non-cooperative polarized state system can embolden outer institution conducts of distrust, stratification, and violent conflicts, which retard development.

References

- North D (2003) The Role of Institutions in Economic Development. United Nations UNECE Discussion Papers Series No. 2003, p. 2.

- Amendola A, Easaw J, Savoia A(2013) Inequality in developing economies: the role of institutional development. Public Choice 155: 43-60.

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2010) The role of Institutions in Growth and Development. Review of Economics and Institutions 1(2).

- Bardhan J (2005) Institutions and Development. Pranab Bardhan University of California, Berkeley.

- Cohen SI (2024) Institutions, Goals, Policies and Analytics in Economic Development. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore.

- Cohen SI (2009) Economic Systems Analysis and Policies: Explaining global differences, transitions, development. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Feindouno S, Goujon M, Wagner L (2016) Internal Violence Index: a composite and quantitative measure of internal violence and crime in developing countries. Fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international, Paris.