A Cross Cultural Insight into Social Capital and Stress Mediation

Cindy Ogolla Jean-Baptiste1*, Christine Ouma2, W Lawrence Beeson3 and R Patti Herring4

1DrPH, MPH, MA; Public Health Analyst, Adjunct Instructor of Health Policy, Researcher at Descendants of Africa Pioneering Innovations, USA

2Assistant Professor of Statistics at University of Cincinnati. Researcher at Descendants of Africa Pioneering Innovations, USA

3Clinical Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Loma Linda University School of Public Health, USA

4Professor, Health Promotion & Education, Loma Linda University School of Public Health, USA

Submission: October 11, 2022; Published: October 27, 2022

*Corresponding author: Cindy Ogolla Jean-Baptiste, DrPH, MPH, MA, Public Health Analyst, Adjunct Instructor of Health Policy, Researcher at Descendants of Africa Pioneering Innovations, USA, Email: caogolla@gmail.com

How to cite this article:Cindy Ogolla J-B, Christine O, W Lawrence B, R Patti H, et al. A Cross Cultural Insight into Social Capital and Stress Mediation. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2022; 8(1): 555726. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2022.08.555726

Abstract

Background: Stressful Life Events (SLEs) have been correlated with adverse health outcomes. Social capital has been shown to mitigate stress effects. Studies have documented demographic specific varying levels and perceptions of social capital by age, race and socioeconomics. We set to investigate demographic perceptions of social capital and how this influenced stress appraisal.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study in 2020 in the US. Participants responded to a 4-variable Likert-like scale on 4 social capital constructs: distract, readily available, stress effect without contact, and routine contact, with options from family, close friends to social and professional groups. We incorporated the Cross-Cultural Stress Scale (CCSS), a 55-item validated toolkit asking participants to indicate their perceived SLE scores, consequently correlated the two.

Results: Survey participants (N=323), ranked social capital accentuating family, friends and coworkers in the top three. Some demographic differences in intensity were reported by all demographics for example: older people relied more on family while younger people relied more on friends for coping. Nonwhites and immigrants relied on extended family and cultural groups to cope and distract them from stress while lower socioeconomic groups reported higher stress without people in their neighborhood and cultural groups. Significant differences in SLEs appraisal were reported; higher severity with lower perceived social capital-particularly cultural and leisure groups by some participants (N=175).

Conclusion: Despite convenience sampling limitations, our results demonstrate varying perceptions of social capital and highlight its significance in mitigating the effects of stress which may translate to better health outcomes.

Keywords: Social Capital; Stressful Life Events; Stress Appraisal; Cross-Cultural

Abbreviations: IP: SLEs: Stressful Life Events; Internet Protocol; CCSS: Cross Cultural Stress Scale; PTSD: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Introduction

Research has documented how lingering psychological stress due to stressful life events (SLEs) play a major role in the decline of our emotional and physical well-being. Several studies have documented morbidity and mortality outcomes due to stress [1-4]. Studies have shown positive correlations between increased community resources and overall health [5-7]. The social capital theory was applied in this study to uncover how the effects of various unique social dimensions existing within communities were associated with individual stress. With such evidence of linkage of greater social capital to substantial positive physical and mental health outcomes, we postulated that perceived social capital would influence which types of SLEs are reported and how they are appraised.

Lazarus & Folkman [8] coined the transactional model of stress and coping. They linked levels of individual stress to the dynamic transaction between the individual and their environment which includes available resources such as coping mechanism. In health psychology, the overall physical and environmental effects of stress are often studied along with mitigating and moderating factors, such as coping and social support [9,10]. Social capital is the collective term for various initiatives available to members of social groups which has been shown to provide individuals and communities resources to deal with adversities [6]. Studies have long demonstrated that variations of stress-related depressive moods depend on individual satisfaction with social capital from available social support systems [5,6,11]. Furthermore, demographic categories, including race, alter how stress impacts depression risk [1].

Theoretical Framework

Lazarus & Folkman [8] suggested cognitive appraisal to be an evaluation of the stress effect on an individual. As a result of their appraisal, an event was categorized as irrelevant, benign, or a threat currently or potentially harmful. The social capital theory describes complex channels and networks within a community that enhance cohesion among individuals through mutual cooperation, norms of reciprocity and other trust building relationships such as civic participation [7]. Theorists such as Kawachi et al. [12] have used a pluralistic approach that unifies key elements resulting in a relative consensus that social capital includes those elements of social networks that can yield positive physical and psychological health. In a recent review of prospective multilevel studies [13] the authors report considerable evidence of an association between social capital and various indicators of health. Several additional studies have documented morbidity and mortality outcomes due to stress, showing correlations between increased community resources and overall health [5-7].

Perception of social support or perceived availability for an individual is just as important as actual presence of social support. Such perception has been shown to predict a positive adjustment to SLEs [14-16]. With such evidence of the linkage of greater social capital to substantial positive physical and mental health outcomes, we postulated that perceived social capital would influence how SLEs are appraised.

Methods

Part of the data reported in this study is included in our larger study which incorporated interviews, focus groups and surveys [17-19]. In our initial study, we investigated SLEs and developed a validated toolkit, the Cross Cultural Stress Scale (CCSS) [18]. We further evaluated stress and social capital as driven by the ongoing pandemic in early 2020 (February-April) [17]. Data shared in this study are derived from surveys conducted through Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) shared on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a crowdsourcing website (https://www.mturk. com) [20]. Survey participants responded to questions on social capital constructs on a Likert scale (1=Very little to none, 2=Less than moderate, 3= A moderate amount, 4= A lot). We condensed these to 2 options for easier analysis where 1 & 2 were merged to ‘Not much’ and 3 & 4 to were merged to ‘Quite a bit’. Dichotomizing the responses was necessary because most of the respondents favored options 1 & 4, with very few opting for 2 & 3. There were four constructs of social capital whose indicators were as follows:

i. I can count on these people/groups to distract me from stress or help me feel more relaxed…

ii. These people/groups are most readily available to help me cope with stressful life events…

iii. Without these people/groups, the stress effect would be…

iv. How often you keep routine contact…

To obtain the total score for each social capital, we summed the original 4-Likert scale responses across the four constructs (distract, readily available, stress effect without contact, how often routine contact). The CCSS ranks 55 SLE’s from 55 to 100, however participants ranked these events even lower, from 1-100 based on their perceived severity if they should experience this. We summed up scores of perceived SLE from all items in a similar fashion as our past study [19] where the maximum score of 5500 would assume a perceived severity of 100 on each SLE. The higher scores of up to 5233 depicted stronger intensity of stress while lower scores such as our observed 225 total illustrated perceived mild stress intensity should respondent experience those. We then correlated these scores with reported social capital.

Participants and Recruitment

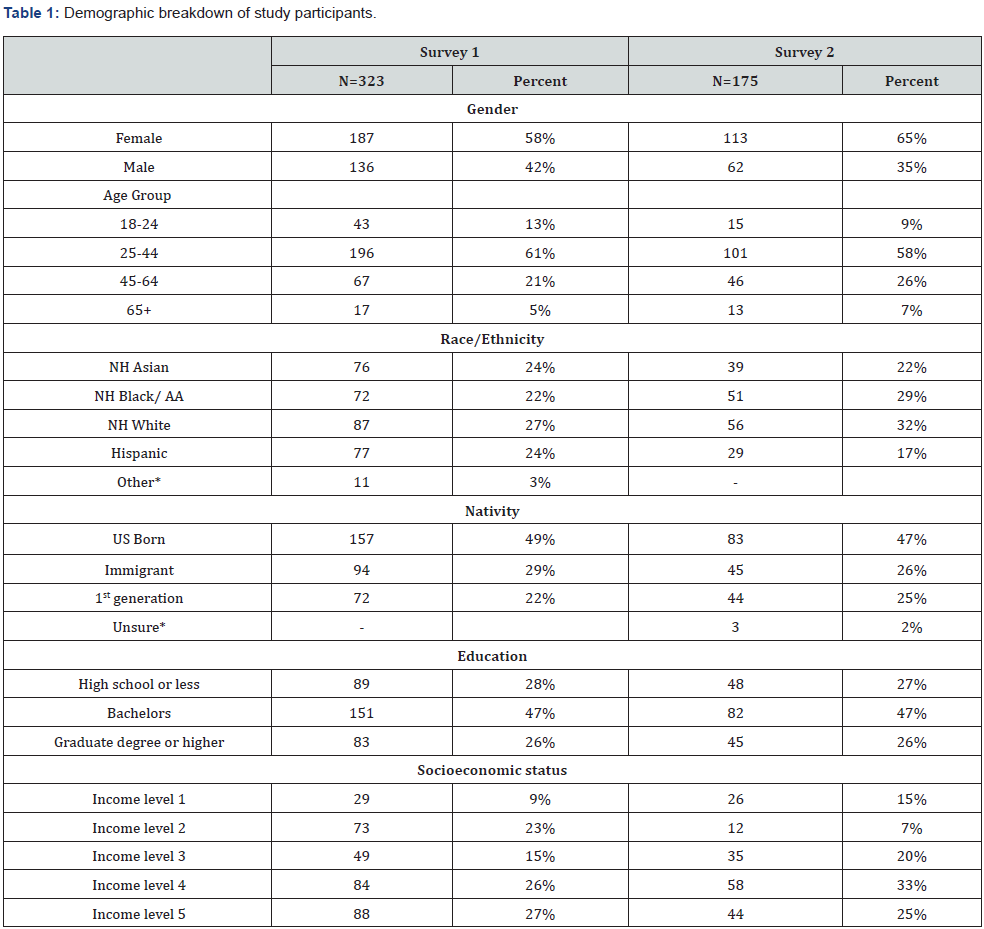

This broad study was approved by Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board. All eligible participants for the study were: (a) over 18 years old, (b) reside currently in the U.S. (i.e., not on a temporary/visitor visa) and (c) able to communicate in and read English. Adult participants from all races/ethnicities, including undocumented U.S. residents, could participate with no verification of status required so long as temporary status was not an issue. A total of 323 survey responses collected were deemed usable to assess social capital and 175 were complete and usable to correlate with appraised SLEs. Internet Protocol (IP) address collection feature was disabled in Qualtrics. Some demographic categories not included in Table 1 had to be eliminated due to sampling difficulties. All participants provided informed consent and had the option to withdraw at any time.

Variables and Instrumentation

The main demographic-specific independent variables of interest included: (a) race - White, Black, Asian and ethnicity- Latino and (b) nativity- immigrant, U.S.-born or 1st generation; (c) we also included additional demographic indicators (e.g., education and economic status); and (d) age in four categories (i.e., 18-24, 25-44, 45-64 and 65+). Key race/ethnicity, nativity/ immigrant status questions were required on the survey instrument to control for missing data. Participants not willing to consent, provide race/ethnic demographics or of temporary visa status (excluding protected and undocumented residents) were exited from the survey via Qualtrics survey logic. As this study is part of a larger study particularly assessing race and nativity variables, declining to provide the race/ethnicity and nativity information would render the data unusable.

Data Analysis

The quantitative survey data were coded and analyzed using SPSS (ver. 26, IBM SPSS, Inc, Armonk, NY). Analyses performed included summary statistics of demographic, social capital, and SLE total variables; correlation to determine if there is a relationship between total social capital scores and total SLE scores; Chi-square square test of independence to determine if there is a relationship between social capital and demographic variables.

Results

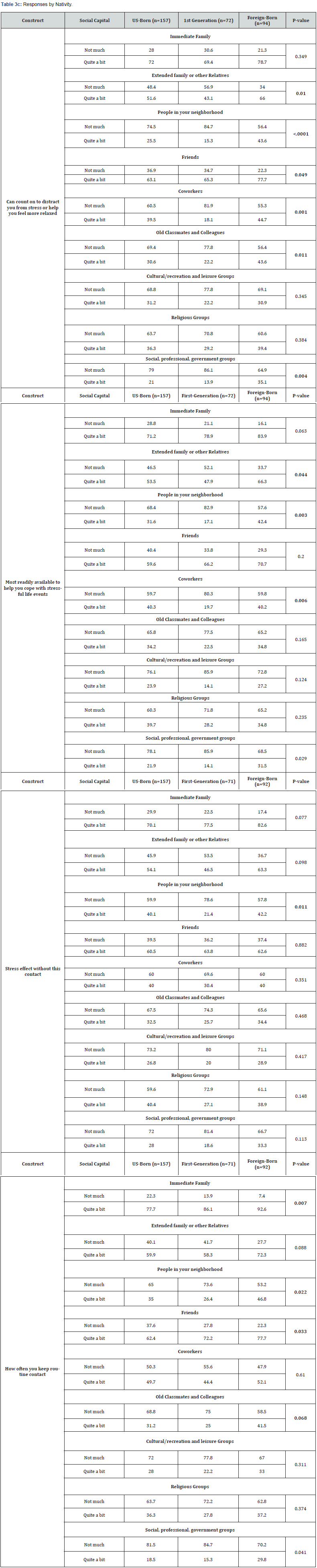

Table 1 shows the breakdown of participants by demographics requested. Due to low response rates from some race demographics, only data from Asian, Black/African American (AA) and White races are reported. All race data are from non-Hispanic individuals. The Hispanic ethnicity is categorized separately. We were particularly interested in the overall weight of social capital from all constructs by nativity as highlighted in Table 2. Within each social capital, there were no significant differences among the nativity groups. The first four social capitals (immediate family, friends, extended family, coworkers) were ranked the same way by all nativity groups. U.S. born individuals ranked religious groups above old classmates, people in the neighborhood, cultural, and social groups. First generation respondents ranked people in the neighborhood above old classmates, religious groups, cultural and social groups. Foreign born respondents ranked old classmates above religious groups, people in the neighborhood, social, and cultural groups.

*Eliminated from analysis

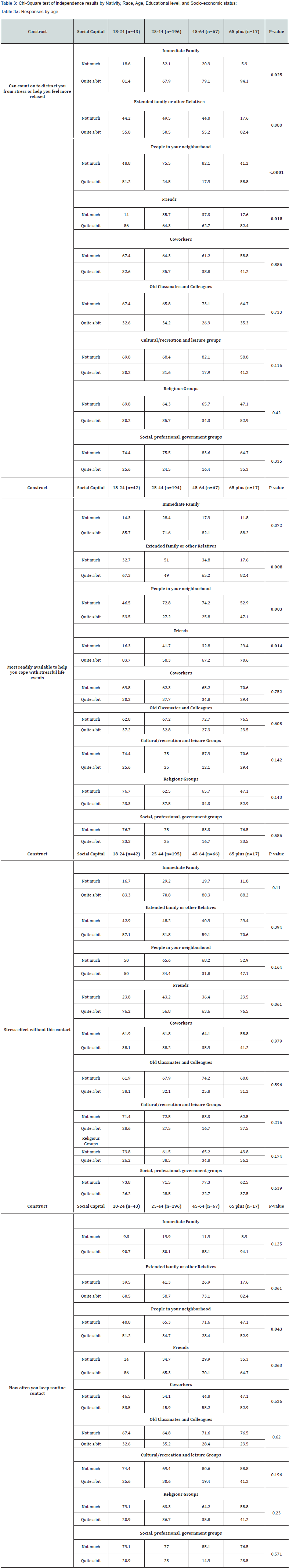

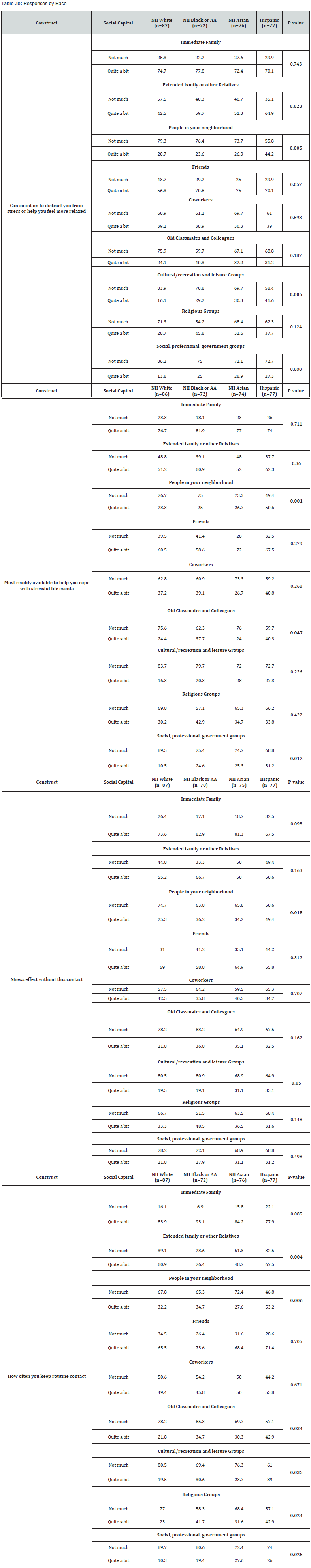

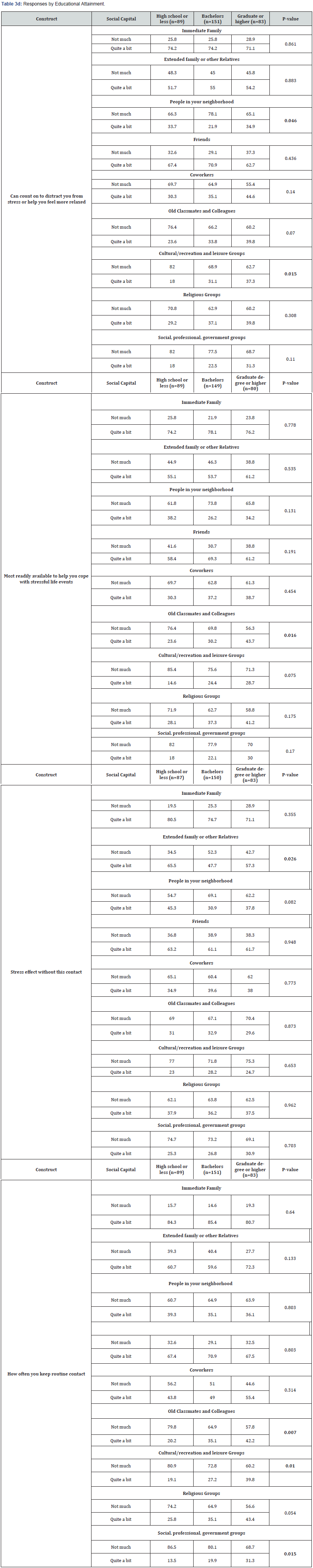

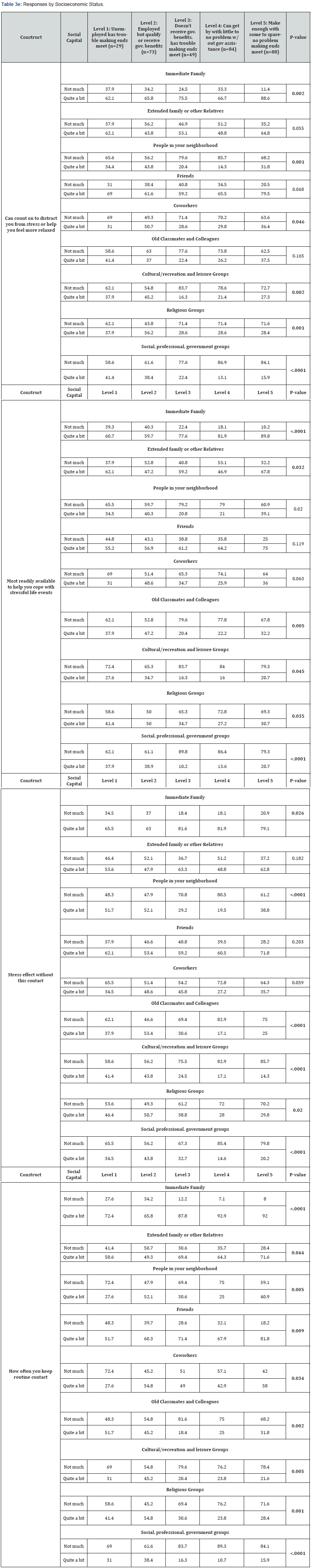

The results of the chi-square tests are presented in Table 3 and its specific sub-tables. The p-values and category percentages are broken down by the constructs of our investigation. The p-values shared highlight multiple demographic-specific significant differences within each construct. Highlights from the significant associations include:

i. A higher percentage of older people (45 and above) can count on immediate family quite a bit to distract them from stress, compared to those in younger age groups.

ii. A higher percentage of younger age groups (44 and below, but especially 24 and below) rely on friends quite a bit to help them cope with stressful life events compared to other age groups.

iii. A higher percentage Hispanics can count on extended family, people in the neighborhood, and cultural and leisure groups quite a bit to distract them from stress, compared to other racial groups.

iv. A higher percentage of non-Hispanic Black individuals often keep routine contact quite a bit with extended family or other relatives compared to other racial groups.

v. In regards to nativity, compared to other groups, a higher percentage of foreign-born individuals can count quite a bit on extended family or other relatives, people in the neighborhood, friends, coworkers, and old classmates and colleagues.

vi. Compared to middle and higher socio-economic groups, a higher percentage of individuals in lower socio-economic would be stressed quite a bit if they didn’t have people in the neighborhood, old classmates, and cultural groups.

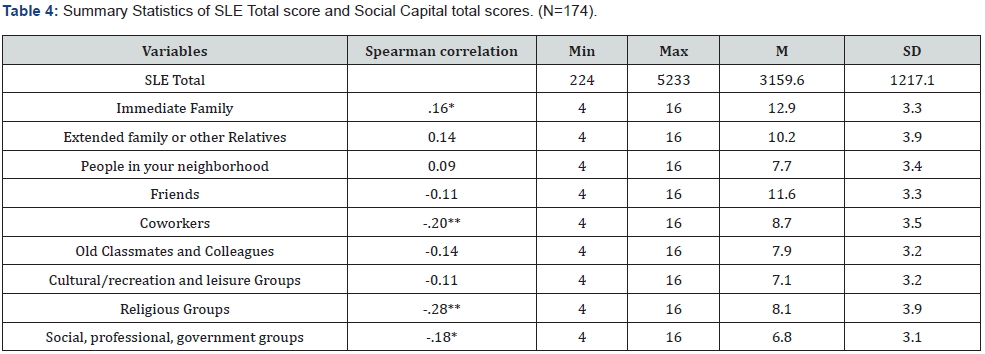

Summary statistics of social capital scores and total SLE are presented in Table 4. We hypothesized an inverse correlation between social capital and ranking of SLEs which was mostly affirmed by our findings except for the first 3 social capital which included family, relatives and people in the neighborhood. In our previous work [19] we linked stressful life events to perceived self-reported social capital. In previous work, we asked participants to rank all the SLEs in our developed toolkit consisting of the Cross-Cultural Stress Scale (CCSS) [18,19] based on their perceived severity. We then used these values for further analysis to correlate with measures of public health significance to ascertain the stress-health link. In this study, we employed the same method, summing up reported scores of stressful life events and in this paper correlate with reported social capital.

*p<.05, **p<.01. The correlation column are correlations between SLE Total and social capital scores.

Discussion

Social capital networks are a mental and psychological health determinant which create shared resources or reciprocity; however, allocation of these is not always not always equal [21]. Results from our quantitative analysis show family (both immediate and extended), friends and coworkers as the highest rated channels of social capital for all groups. We hypothesized that some demographic groups are likely to perceive lower levels of available social support and consequently rank SLEs considerably higher. Our results demonstrate significant differences in optimism which aligns with previous work alluding to individual differences in optimism that influence in the adjustment to stressful life events [16]. Social isolation is exhibited along racial and ethnic lines, and might be worse for immigrants [22]. Our results support this hypothesis with multiple significant differences within the social constructs, not only by nativity, but also by other study demographic variables. For the distraction construct, Hispanics were more likely to count on extended family quite a bit to distract them from stress or help them feel more relaxed compared to other racial groups. Similarly, individuals age of 65 and older were more likely to count quite a bit on immediate family, extended family, and people in the neighborhood to distract them from stress or help them feel more relaxed compared to individuals under the aged of 65. The findings also revealed that people of high social economic status were more likely to keep routine contact quite a bit with all the social capital categories compared to those in middle or low socio-economic status. Our findings are consistent with recent research [23] which implies that social ties can serve as a literal lifeline during times of need particularly for the elderly and those who are socioeconomically challenged.

Our correlation of social capital and appraisal of SLEs yielded small but statistically significant associations. The higher the participants appraised stress, the lower their perceived social capital was based on our constructs of measurement particularly on a macro level. It is possible that often SLEs being faced involve those closest contacts and external links such as the ones showing negative correlations in Table 4 are most effective for support. The ‘social’ in social capital is thus profound towards stress moderation. While the more personal forms of social capital were ranked highest overall, particularly by nativity as depicted in Table 2, it is possible that the other social and communal social capital come with unique resources that directly target the stressors, which explains the negative association at the macro level. In the literature, a recent study by An S et al. [24] describe the depression vulnerability of older adults with reduced community social capital. Another study by Ansman et al. [25] measured organizational social capital confirming associations between employee engagement, burnout and overall stress.

The authors uphold communal social capital to contribute to both individual wellbeing and organizational performance. Lastly, Flores et al. [26] set to investigate association of cognitive and structural social capital and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the Peru 2017 earthquake survivors. Their measures of cognitive social capital included trust, sense of belonging and interpersonal relationships, closely aligned with our four constructs of measurement. They described structural social capital as actual support and involvement in community groups. The authors reported independent association of cognitive social capital with lower prevalence of chronic PTSD among survivors. They found a prevalence of almost twice as much PTSD among participants indicating low cognitive social capital. We presented the notion that perception of social support or perceived availability for an individual is just as important as actual presence of social support which is supported by Flores’ team’s findings of no association between structural social capital and PTSD. Participants from our previous study indicated potential dire consequences had they not been able to interact somewhat on a large scale with the broader community particularly due to the uncertainty during the earlier onset of the COVID19 pandemic [17].

Our data do not clarify why or how social capital is related to health outcomes, a notion that is further handicapped by the limited prospective epidemiologic evidence on the effects of social capital on health [13]. The theory proposed is that the social capital and health association integrated with social interpersonal and community mechanisms may be mediated or moderated by those mechanisms [12], for instance individual and psychosocial coping and various forms of social or even professional support. Conclusively, such perception has been shown to predict a positive adjustment to SLEs [11,12,16] and moderation of negative behaviors such as binge drinking [27], child maltreatment [28] and violent crime [29]. We are limited in comparison with other studies as social capital is a growing field and very few researchers have delved into demographic-specific differences To our knowledge, our research is the first of its kind assessing the 4 constructs stratified by demographics we incorporated and linking the CCSS.

Conclusion

Life events provide an overview of a community’s wellbeing and have been used as markers for health outcomes. Social capital studies are growing, and findings will be especially relevant for a population whose livelihood has included a global catastrophic pandemic with survival measures that includes decrowding, minimized personal or face-to-face interaction and social distancing. In this study, we set to connect the social capital theory with the issue of SLEs based on Lazarus & Folkman [8] who argued that the way people appraise life events influence the way they appraise experiences. By adding up total scores of appraised SLEs, we were able to affirm that those whose social capital constructs ranked lower largely appraised stress much higher than those who reported higher social capital especially on a macro level. Findings from this study are fundamental in cross cultural and comprehensive stress ratings. The quality of social networks defined by the availability and extent to which they can be relied on for social support can influence psychological wellbeing16. Understanding demographics specific appraisals and availability of social capital at the individual and community level is important to build or expand applicable social networks. As no specific channel of social capital holds weight above the other equally for different demographics, adopting multilevel approaches that incorporate both individual and community connectedness may exert maximum effect on health. Our ability to cope with the life events from social connections also determines how we experience, or rate SLEs such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Lastly, available or perceived social capital is a critical stress determinant that should not be ignored.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board. All study participants provided informed consent and had the option to decline or withdraw from participation at any time. No identifying information was requested. Anonymity was maintained through coded names for interview or focus group participation. Web-based survey did not query for any identifying information, and participants were reminded to maintain their anonymity. Unexpected interview personal identifiers were anonymized in the analytical datafile to prevent participants from being identified from any sensitive information that may have been inadvertently shared. All eligible participants equally participated in all aspects of the study selected. Completed transcripts have no personal identifiers. The Internet Protocol (IP) address collection feature was disabled on Qualtrics. All research information including interview recordings is stored in password protected shared folder hosted on a cloudbased portal only accessible to the study team.

References

- Assari S, Lankarani MM (2016) Stressful Life Events and Risk of Depression 25 Years Later: Race and Gender Differences. Frontiers in Public Health 4: 49.

- Feeney J, Dooley C, Finucane C, Kenny RA (2015) Stressful life events and orthostatic blood pressure recovery in older adults. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 34(7): 765-774.

- Rafanelli C, Roncuzzi R, Milaneschi Y, Tomba E, Colistro MC, et al. (2005) Stressful life events, depression and demoralization as risk factors for acute coronary heart disease. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 74(3): 179-184.

- Cohen S, Murphy MLM, Prather AA (2019) Ten Surprising Facts About Stressful Life Events and Disease Risk. Annual Review of Psychology 70: 577-597.

- Nakhaie R, Arnold R (2010) A four year (1996-2000) analysis of social capital and health status of Canadians: the difference that love makes. Social Science and Medicine 71(5): 1037-1044.

- Wind TR, Villalonga-Olives E (2019) Social capital interventions in public health: moving towards why social capital matters for health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 73: 793-795.

- McKenzie JF, Neiger BL, Thackeray R (2017) Planning, implementing, and evaluating health promotion programs : a primer. Seventh edition. ed. Hoboken, USA: Pearson Higher Education.

- Lazarus RS & Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Pub. Co..

- Hobfoll SE (1998) Stress, culture, and community : the psychology and philosophy of stress. New York: Plenum Press.

- Ward AM, Jones A, Phillips DI (2003) Stress, disease and 'joined-up' science. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 96(7): 463-464.

- Krause N, Liang J, Yatomi N (1989) Satisfaction with social support and depressive symptoms: a panel analysis. Psychology and Aging 4(1): 88-97.

- Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D (2008) Social capital and health. Springer, London: New York.

- Murayama H, Fujiwara Y, Kawachi I (2012) Social capital and health: a review of prospective multilevel studies. Journal of epidemiology 22(3): 179-187.

- Stroebe W, Stroebe Ms, Abakoumkin G, Schut HAW (1996) The role of loneliness and social support in adjustment to loss: A test of attachment versus stress theory [Reprint of Stroebe et al., 1996]. In: 2003: 390-402.

- Han S (2019) Social capital and perceived stress: The role of social context. Journal of affective disorders 250: 186-192.

- Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS (2002) The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of personality and social psychology 82(1): 102-111.

- Jean-Baptiste CO, Herring RP, Beeson WL, Dos Santos H, Banta JE (2020) Stressful life events and social capital during the early phase of COVID-19 in the U.S. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 2(1): 100057.

- Jean-Baptiste CO, Herring RP, Beeson WL, Banta JE, Dos Santos H (2020) Development of the cross-cultural stress scale. Minerva Psichiatrica 61(4): 131-142.

- Jean-Baptiste CO, Herring RP, Beeson WL, Banta JE, Dos Santos H (2021) Assessing the validity, reliability and efficacy of the Cross-Cultural Stress Scale (CCSS) for psychosomatic studies. Journal of affective disorders 282: 1110-1119.

- Litman L, Robinson J, Abberbock T (2016) TurkPrime. com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences 49(1-10): 433-442.

- Coleman JW (1988) Competition and the Structure of Industrial Society: Reply to Braithwaite. American Journal of Sociology. 94(3): 632-636.

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S (2012) More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social science & medicine (1982) 75(12): 2099-2106.

- Ye M, Aldrich DP (2019) Substitute or complement? How social capital, age and socioeconomic status interacted to impact mortality in Japan's 3/11 tsunami. SSM - population health 7: 100403.

- An S, Jung H, Lee S (2019) Moderating Effects of Community Social Capital on Depression in Later Years of Life: A Latent Interaction Model. Clinical gerontologist 42(1): 70-79.

- Ansmann L, Hower KI, Wirtz MA, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, et al. (2020) Measuring social capital of healthcare organizations reported by employees for creating positive workplaces - validation of the SOCAPO-E instrument. BMC health services research 20(1): 272.

- Flores EC, Carnero AM, Bayer AM (2014) Social capital and chronic post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of the 2007 earthquake in Pisco, Peru. Social science & medicine (1982) 101: 9-17.

- Villalonga-Olives E, Almansa J, Shaya F, Kawachi I (2020) Perceived social capital and binge drinking in older adults: The Health and Retirement Study, US data from 2006-2014. Drug and alcohol dependence 214: 108099.

- Nawa N, Isumi A, Fujiwara T (2018) Community-level social capital, parental psychological distress, and child physical abuse: a multilevel mediation analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 53(11): 1221-1229.

- Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D, Lochner K, Gupta V (1998) Social capital, income inequality, and firearm violent crime. Social science & medicine (1982) 47(1): 7-17.