The Environment-Human Migration Nexus: An Empirical Overview

Sweta Tiwari1,2* and Shrinidhi Ambinakudige3

1ARCTICenter, University of Northern Iowa, USA

2Department of Geography, University of Northern Iowa, USA

3Department of Geosciences, Mississippi State University, USA

Submission: July 18, 2022; Published: October 19, 2022

*Corresponding author: Sweta Tiwari, ARCTI Center, Department of Geography, University of Northern Iowa, USA

How to cite this article:Sweta T, Shrinidhi A. The Environment-Human Migration Nexus: An Empirical Overview. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2022; 7(5): 555724. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2022.07.555724

Abstract

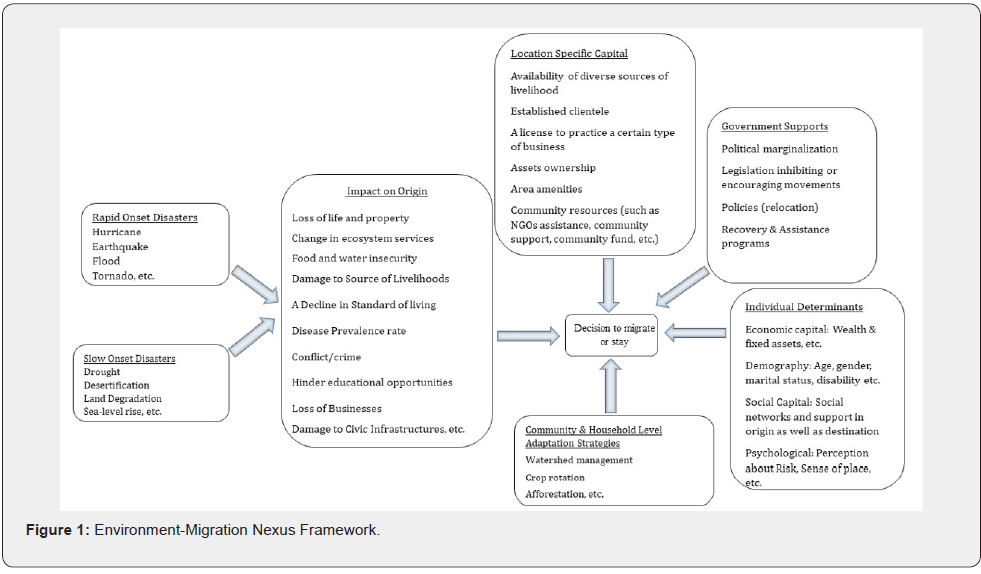

Nature is an active agent in the environment-induced human migration seems to be logical in explaining the large, forecasted estimates of the climate-displaced people by environmentalists. However, migration scholars and researchers have largely ignored this direct causal relationship. To ascertain whether people’s decisions to stay or leave are directly proportional to the environmental crisis they face, this paper analyzes the various empirical and theoretical studies on this subject. Analysis of the real-life instances suggests that environmental changes are a contextual factor and trigger migration only when intertwined with other divers of migration. Moreover, migration outcomes, either no or out or return, are a function of the aggregated adaptive capacity of actors at different scales. Based on these premises, this paper presented the Environment-Migration Nexus Framework. This framework highlights the impact of climate stressors on humans, and migration, as an adaptive response, is influenced by individual characteristics, location-specific capital, the government supports, and household- and community-level adaptation strategies. Consideration of this framework might provide the researchers in this field with a more accurate and broader picture of migration in the context of climate change.

Keywords: Climate Change; Migration; Adaptation; Vulnerability; Human Agency

Introduction

In recent years, Earth’s climate has changed unprecedently. It is evident through the increase in the frequency of extreme weather events (such as tropical cyclones, hurricanes, and heatwaves), the rise in average global temperatures by about 1 degree Celsius since 1850 [1], widespread changes in precipitation patterns (including droughts and floods), and an average of 3 mm rise in sea level per year [2,3]. The unprecedented change in Earth’s climate with human-caused environmental degradation has increased people’s vulnerability by severely affecting their lives and livelihoods. In such a situation, migration could be one of the adaptive strategies for vulnerable people to cope with these adverse environmental conditions [4-6].

Environmental scholars and institutions explicitly linked migration to environmental change [3,7,8], while migration scholars and researchers have largely ignored this direct causal relationship [9-11]. Many environmentalists, based on Neo-Malthusian theory and the Earth’s deteriorating conditions, provided the large, forecasted estimates of climate migrants, [3,8,12,13]. The deterministic approach, large, forecasted estimate of climate migrants, and not accounting for the return of displaced people drew critical responses [14-16]. The main drawback of the deterministic approach is that it does not consider the role of human agency in migration outcomes, thus ignoring the capability of communities and developing countries to cope with environmental events [17,18].

To determine whether people’s decisions to stay or move are directly or implicitly dependent on climate events, this paper analyzes the various empirical studies on this subject. First, we provide a summary of the deterministic approach. Then, we give a brief overview of critiques of migration scholars, migration theories, and empirical studies in explaining the environment-migration nexus. Finally, based on various real-life instances and empirical studies, we present the conceptual framework describing the environment-migration nexus more comprehensively.

The Environmental Deterministic Approach

Human mobility due to environmental changes can be traced back to the earliest period of human history. Every 21,000 years during the late Pleistocene epoch, the Earth’s axis wobbled and caused shifts in climate from cold and arid to warm and humid summers in the Northern Hemisphere, which created green corridors between Africa and Eurasia and enabled homo sapiens to move out of Africa [19]. Humans were then assumed to migrate from Eurasia to Australia and then America through the land bridges exposed because of lower sea levels during the glacial maxima [20]. For over 99% of their history, humans were nomads whose livelihoods often depended on seasonal movement [21]. Even today, for instance, farmers in the arid Sheeb region, Eritrea, during flood season, would migrate to upland areas while awaiting the floods in the lower valleys, which they captured for spate irrigation [22]. Similarly, the Saami reindeer herders living in northern Scandinavian often migrate with their herd to coastal grounds away from the permanent home base to escape harsh winter conditions [23]. Even though humans adopted a sedentary lifestyle after the agricultural revolution around 12,000-10,000 B.C. [24], climate change and environmental degradation, among many reasons (such as war, and the industrial revolution), have forced humans to move.

On the foundation of the Neo-Malthusian theory of population growth and the increasing trend in climate change (e.g., raising sea levels and temperatures, unpredictable precipitation patterns, more frequent storms, and geophysical activities), the environmental scholars assumed nature as an active causal agent in human migration, inducing massive population displacement [3,8,10,25]. By 2050, the predicted estimates of the climate displaced people by Myers & Kent [25] were approximately 200 million, and by Riguard et al. [3] was 143 million, among others. These massive estimates of displaced people and the theory behind these estimates drew critical responses from researchers and migration scholars [26-30]. These estimates were based on the ground that all people living in the regions at risk were and would force to move due to the environmental changes, while there was no clear demarcation of whether the environmental changes were the main or contextual factor triggering migration. Although questionable, the projected estimates of climatedisplaced individuals and the theory behind them were widely cited in various studies and reports to emphasize the Earth’s deteriorating conditions in terms of human habitat suitability, advocate for humanitarian charities, and lobby the concerned parties on the formulation and implementation of climate refugee and environment protection measures or policies. Such reports and studies include the work of Lukyanets et al. [31], the Lancet Countdown [32], Ajibade et al. [33], the Norwegian Refugee Council [34], Biermann & Boas [35], the Geneva-based Global Humanitarian Forum [36], and Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change [37], among others.

The Environment-Migration Nexus: as a Complex Phenomenon

By arguing that migration is a complex phenomenon induced by the interplay of economic, social, political, and environmental factors, many researchers have questioned the direct causal relationship between environmental change and migration. Black et al. [11], based on their empirical analysis, found that the main reasons behind people migrating were almost always economic and social factors. Even in the high-risk climate hazard regions, climate change was rarely the main reason for the people movement [9]. According to a survey conducted by Safra de Campos et al. [38], out of 2310 households inhabiting low-lying coastal areas in India and Bangladesh, only less than 3 percent of respondents mentioned climate stress as the main reason for their migration, while a large number of people mentioned employment, education, and marriage were the primary factors for their movement.

Vigdor [39] found that Hurricane Katrina was not the active agent but the catalyst in out-migration. Even before Katrina, the city of New Orleans had been experiencing a fall in employment level in traditional sectors like manufacturing thereby a gradual population decline [39]. Thus, the occurrence of Katrina accelerated the already ongoing out-migration. Furthermore, four decades of armed conflict intertwined with the prolonged drought was a tipping point for many Afghans leading to the displacement of more than 371,000 people in 2018 [40]. Tower [41] argued that in the Lake Chad Basin, given conflict as the primary migration driver, the political and climate stress (i.e., the insurgency of Boko Haram against the Nigerian government and the diminishing lake) together deeply impacted and mostly displaced the population dependent on subsistence farming.

McLeman [42] argued that environmental migration research emanated from other fields like climate science, political science, and law. Thus, he emphasized not getting trapped in environmental determinism, and essentially acknowledging the theoretically grounded research on migration behavior. Scholars have relied on migration theories at the macro, micro, and meso levels to describe how environmental change leads to migration [10,43- 45]. Macro-level theories such as the neoclassical macroeconomic theory, the dual labor market theory, and Wallerstein’s world system theory generally concentrate on labor and capital markets, primary and secondary sectors, and capitalist economy at the national or international levels [46-47]. Micro-level theories such as the neoclassical micro-migration theory, Wolpert’s stressthreshold model, the value-expectancy model, Lee’s push and pull theory focus on the influence of individuals’ characteristics on migration decisions such as individual’s personally valued goals, and his calculations of cost-benefit, age, gender, marital status, and education and the role of place utilities and stressors in origin and destination [46,47]. Meso-level theories such as network theory, institutional theory, and cumulative causation theory focus on the role of the linkage system such as migrants’ social network and structure, and private institutions between two places that facilitate or intervene in migration [46-48].

Many researchers also emphasize return migration and the role of states, communities, and human agencies in migration outcomes which were completely ignored in the deterministic approach [14,15,17,25]. Further, either in extreme weather events or slow-onset disasters, peoples’ decisions to migrate are often dependent on the aggregated adaptive capacity of actors at all scales—macro, meso, and micro [42,49,50].

Role of Government or Non-government Organizations

At the macro scale, the government’s housing assistance and means to restore sources of income play an important role in resettling people back in disaster-affected areas. In the aftermath of hurricanes, 2017 Harvey and 2018 Florence, and the 2021 Western Kentucky Tornado, the formulation and implementation of assistance programs by the U.S. and respective state governments helped people living in the affected areas to rehabilitate, reconstruct, and restore their houses and sources of income. Examples of these programs were buyouts and acquisitions, homeowner repair and reimbursement, allocation of funds for utilities and road infrastructures repair, small business loans and grants, and disaster unemployment assistance, among others [51-53]. Similarly, emergency housing response programs by the state government, the Red Cross, and FEMA have helped to house nearly 2600 individuals in Western Kentucky after the 2021 Tornado [53]. These programs would definitely decrease permanent out-migration and increase the proportion of the displaced individuals who would likely return home.

Even in countries with weak formal government institutions, such as Nepal, prompt assistance in the form of food grains, safe drinking water, sanitation services, hygiene kits, and tarpaulins from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) [such as the Red Cross, United Nations agencies like UNICEF, and USAID], and the mobilization of 300 volunteers by the Non-Resident Nepali Association (NRNA) for relief and reconstruction has enabled Nepalese communities to recover quickly from the 2015 earthquake without large-scale permanent displacement [54]. Similarly, various UN agencies (including IOM, and UNICEF), local partners, and local authorities had worked together to avail food, various shelter and household items (such as durable roofing materials, tents, blankets, kitchen sets), and other assistance to distressed communities in the aftermath of 2019 two consecutive category four tropical cyclones, Idai and Kenneth struck Mozambique [55,56]. Such disaster responses, in part, might have played a role in fewer displacements (i.e., as of December 31, 2019, the displacement of 100,159 out of 1,800,944 individuals affected) [56]. During 2017 when a severe drought in Kenya triggered a national emergency, the Kenya Red Cross Society supported 3,447 households in the drought-affected communities across Samburu by giving them 3,000 Kenyan shillings per month, healthcare services, in-kind and cash-based food assistance [57,58]. Likewise, after the devasting tsunami event of December 26, 2004, the Canadian Red Cross with the Indonesian Red Cross Society introduced the Integrated Community-Based Risk Reduction (ICBBR) program to build disaster-resilient communities in 43 villages of Aceh and Nias Islands, Indonesia [59]. Disaster relief and emergency assistance, and disaster resilience programs, as part of the recovery and disaster risk reduction efforts, would undoubtedly reduce the vulnerability of the affected people and outmigration.

The approach of most countries or communities today in addressing natural disasters is more prospective than retrospective. Over the last two decades, European countries are actively investing in various flood prevention measures, including flood protective structures (e.g., the Machlanddamm project in Austria, the Cross Border Planning, and Infrastructure Measures for Flood Protection project in Struma/Strymon and Evros/Maritsa River basin located in Bulgaria and Greece), and landscape restoration (e.g., Eddleston Water Project in Scotland, Padgate River Restoration project in Warrington, UK) [60]. The introduction of artificial dunes in Nile Delta coastal zones proved to be effective in protecting against the hazard related to sea level rise [61]. The municipal government of Pune, India, had worked in conjunction with local partners to implement a city-wide action plan for restoring natural drainage, widening streams, extending bridges, and employing natural soil infiltration methodologies to prevent periodic flooding [62].

The wetland restoration program initiated by the Hubei Province of China rehabilitated 448 square km of wetlands with a capacity to store up to 285 million cubic meters of flood water. In addition to flood prevention, the wetland restoration program has enhanced biodiversity, increased income from fisheries, and improved water quality [62]. The 1997 building codes of the Chilean government, which enforced all new buildings to be designed and constructed in the confined masonry style, resulted in a lower number of casualties when an 8.8 magnitude on Ritcher scale earthquake struck central Chile compared to a 7.0 magnitude earthquake hit Haiti causing over 200,000 deaths in January 2010 [63]. The communities in and around Houma, Louisiana, have launched self-initiative measures, such as marsh restoration, elevating existing homes, improving pump systems and canal drainage, and self-funded levees, to prevent and combat regular flood events and storm surges [64]. These prevention efforts, which safeguard people’s homes and enhance their source of livelihood, would absolutely lower people’s vulnerability, thereby inhibiting their mobility.

Role of Human Agency

At micro levels, people’s capacity to uproot or stay in the face of environmental change is a function of their households’ economic, social and location-specific capitals and demographic compositions. Poor people are more vulnerable to climaterelated changes than wealthier people [65-67]. Many poor and marginalized people, particularly in developing countries like Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Manila, live in areas prone to natural hazards (such as flooding, slope failure, or low-lying coastal wetlands), occupy fragile houses, and have limited access to resources, therefore having a greater risk of displacement [42]. Even though experiencing high hazard risk, if the affected areas have diverse livelihood options and safety nets, people are less likely to migrate in response to climatic stress. Migration in response to rainfall-related stress was a matter of choice for the people of four villages ((i.e., Don-Moon, Sandonhom, Maebon-Tai, and Huai-Ping) living in Lamphun province in northern Thailand due to the availability of diverse livelihood options, access to financial resources through community funds, and assistance from the local government [68]. In the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh, an area prone to river erosion and high rainfall, the availability of diverse livelihood options (e.g., agriculture, shrimp farming, business, extracting natural resources from Sundarbans) has, somehow, encouraged a large number of people to stay [69].

Migration can be one of the appropriate adaptation strategies for poor people living in climate-stress areas with scant livelihood diversification options. However, limited economic capital and resources could make migration a nonviable adaptation strategy [70]. As migration incurs financial costs, such as travel and resettlement, not all the people living in regions at risk could afford it. A study conducted by Nawrotzki & DeWaard [71] in 55 districts of Zambia found that climate-related immobility was pronounced in the most economically disadvantaged areas. Similarly, degradation in soil quality severely affected the people’s income from agriculture, thus restricting most Ugandan mobility [72].

Even if the affected households have the capacity to migrate, various studies have shown that neither every household nor all members of a household migrate in the context of environmental change. For instance, farmers of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, who own rice fields, were less likely to migrate in response to floods than landless farmers [62]. Similarly, during the 1930s Dust Bowl in the U.S., the out-migration of tenant farmers and young working families was high compared to the landowners and elderly population from drought-stricken areas [73]. While in Thailand, even during periods of prolonged climatic stress, women, regardless of land ownership, were found least likely to migrate [74].

In four villages in the Kurigram district of Bangladesh, in the mestizo communities of Southern Ecuadorian Andes, and the rural communities of Tajikistan, agricultural shock due to unexpected fluctuation in precipitation and land degradation have significantly increased the migration of male members of households as compared to female [75-77]. Jungehülsing [78] found that in the aftermath of Hurricanes Mitch and Stan, the migration rate of single mothers and young single adults was higher than in other groups in Soconusco, Sierra, and Costa regions of Chiapas, Mexico. Likewise, families generally send their children to stay with their relatives living elsewhere to reduce pressure on household resources and to cope with food shortages during prolonged dry periods in the West African Sahel [79,80]. Disability is another individual characteristic that often inhibits mobility during a disaster. The main reasons disabled people were reluctant to evacuate during the 2010 New Zealand Earthquake were fear of losing various forms of social-support networks and unfamiliarity with a new neighborhood [81].

Not just the demographic characteristics, but peoples’ social and location-specific capitals also determine migration. Residents of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, gave little serious consideration to leaving their homes during flood seasons as the ongoing deposition of soils and nutrients from runoff and periodic overspilling of channels enhance agricultural productivity [82]. Even after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, BP’s Macondo Oil well rupture, rising sea level, and the sharp decline in sea-food prices, the main reasons for many residents of Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, did not leave include the affective bond between people and place, the value these people provide to their cultural capital, and limited resources [83]. Research has shown that residents with strong place attachments were less likely to leave even hazard-prone areas [84-86]. In the same way, social resources, such as assistance from caregivers, neighbors, and family in terms of short-term borrowing, remittance, free shelter, and reassurance recovered the affected people, therefore inhibited, to a great extent, outmigration in the aftermath of the severe flood in Kuruwita and Elapatha district, Sri Lanka [87], the 2020 hurricanes in two-semi coastal communities in Mexico (Cohen-Salgado et al. 2021), the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake in 27 coastal cities of Iwate and Miyagi, Japan [88], and the 2009 cyclone Aila [89].

Besides discouraging migration, location-specific and social capitals often play a vital role in inhibiting or return migration. Greon and Polivka [90] argued that an individual’s social network, sense of place, concrete assets, job seniority, an established clientele, a license to practice a particular profession, and an area’s amenities, among others, were essential determinants of return migration in the affected areas. Further, various studies have found that social capital and a sense of community bonding reduced barriers to collective action, allowing the mobilization of residents in rescue and relief efforts and their participation in the rebuilding process after a natural disaster, thereby facilitating speedy recovery and encouraging them to stay [91-93]. The community ties encouraged residents of Village de L’Est to participate in the rebuilding process aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Under the leadership of the Mary Queen of Vietnam Church and its new Community Development Corporation, residents have rebuilt most of the community’s single-family homes and a new health center, charter school, and senior housing [94]. Two years after the levees broke, the repopulation (i.e., of the returned migrants and new residents) and the business recovery rates were high in the village [94].

Alongside social and location-specific capital, sometimes household and community levels adaptation would be adequate in restoring people’s livelihood, particularly in the case of slowonset disasters, thus limiting migration. To mitigate the impacts of exacerbated coastal erosion in Demak, Central Java, the Indonesian Red Cross, the village authorities, local people, and scientists from the Bogor Agricultural Institute together implemented programs such as mangrove plantation and crab cultivation [95]. In response to the 2009-2012 Dzud hazards in Mongolia, numerous husbandry strategies, including the introduction of new selective breeds, the use of traditional herding knowledge and techniques, adjusting animal types and herd structure as per the carrying capacity of the pasturelands, rainwater harvesting and creation of water pools for animals use, and irrigation were adopted [96]. In three districts across northeast Ghana, smallholder farmers have employed several practices (such as planting of crop varieties, use of Indigenous knowledge, intensification of irrigation, crop diversification, mixed farming, and sustainable land management practices, among others) to address the threats posed by unpredictable rainfall patterns [97]. People living in vulnerable riverine char islands of Bangladesh adopted similar agricultural strategies [98].

Environmental migration as a temporary, Internal, and urban phenomenon

Very few studies have suggested that the interplay between various factors (economic factors such as poverty, wages, political conflict, or violence, among others) and climate events could act as tipping points for cross borders migration [99-102]. Burzynski et al. [101], Massey [103], Zickgraf [104], and Beine et al. [105]. claimed that the availability of economic opportunities, already existing migrant network, and colonial ties would influence the relocation of many people across borders due to climate stress and their choice of destination (i.e., emigration to neighboring countries, and from the Global South to the Global North).

While a sizeable number of studies, to date, showed that mobility in response to climate events, whether slow or rapid onset events, has been a short-term and internal phenomenon [5,106,107]. A survey of 2,191 rural communes in 63 provinces of Vietnam conducted by Berlemann & Tran [108] found that occurring tropical storms would result in at least one temporary migrant from each affected household, and these migrants often moved toward the larger cities. In Kiribati (a country in Oceania), one in seven people moved from 2005 to 2015 due to environmental change, and most movements were internal towards South Tarawa, an urban area with a very high population density [109]. Bangladesh’s union-level (the lowest administrative unit in rural Bangladesh) study conducted by Chumky et al. [110] found that major spatial and temporal patterns of disasterinduced migration were temporary and from rural to urban areas. A study by Baez et al. [111] of eight countries (i.e., Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Haiti, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama) in Northern Latin America and the Caribbean revealed that youth exhibited shorter distance mobility to the areas where nearby off-farm employment opportunities were ample when confronted with drought. Didenko et al. [112] pinpointed that in 2019, India, the Philippines, the United States, China, and Indonesia had the most noticeable internal migration due to climatic factors, such as storms and floods. One consistent finding in these studies was that climate event was rarely a push factor for long-term and cross-border migration. Further, evidence from Tajikistan, the Philippines, and Nepal reflected that sudden onset environmental shocks appeared to have a dampening effect on international migration [113-115].

Conceptual Framework for Environmental Migration

Based on the above studies, this paper presents a framework, “Environment-Migration Nexus Framework”, that portrays how migration decisions are shaped by the aggregate role of actors at all scales (macro, meso, and micro) in the context of environmental change. This framework, shown in Figure 1, explicitly highlights the consequences of rapid- and slow-onset natural hazards in a location in terms of human habitability and the influence of various determinants of all scales shaping decisions to stay or migrate.

Rapid-onset disasters, by damaging lives, livelihoods, and civic infrastructure, exert direct pressure on people to leave the affected areas and settle elsewhere. In September 2017, many people moved, when the earthquakes of 8.2 and 7.1 magnitudes on the Richter scales damaged more than 184,000 houses, 175 health facilities, and 16,000 schools on the central and southern coast of Mexico [116]. In the year 2018 alone, sudden-onset hazards resulted in 17.2 million new migrants, out of which 7.9 million migrants were the result of storms, particularly cyclones, hurricanes, and typhoons, and 1.1 million due to earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions [40]. On the other hand, the loss of crops or decline in agricultural productivity due to slow-onset disasters (such as floods, drought, and desertification) could act as catalysts for famine, forcing people to move. Each year, over 400,000 people in rural Mali are affected by the drought and intercommunity unrest, and these interlinked triggers exacerbated food insecurity, thus forcing people to flee their homes [117].

Whether the impacts are prompt or gradual, direct or indirect, the rapid- or slow-onset disasters accentuate outmigration by altering the ecosystem services of the affected areas. The consequences of alterations in ecosystem services for humans include, at the very least, a decline in sources of livelihood, food shortages, water contamination, and an increase in disease prevalence. The floods of 2019 and 2020 and locust infestation in their aftermath led to a huge loss of crops that worsened the ongoing food crisis in Somalia and triggered 979,000 new displacements in 2020 [118].

Chances of post-disaster diseases (i.e., water- and mosquitoborne diseases) outbreaks and their spread increase with the overcrowding, disruptions of the sewage system, lack of sanitation facilities, and limited access to health care services in the affected area [119-121]. Furthermore, the probability of conflict will be high in an underserved area, where many people depend on limited resources or a community is marginalized [122,123]. In such a situation, people residing in the area might choose migration as a form of adaptation strategy if they are not income constrained and facilitated by their social capital. In Syria, frequent droughts and multi-year crop failure forced most rural families to move toward cities, which resulted in overcrowding and increased unemployment and inequality, leading to political unrest and protracted displacement since 2011 [117]. When the four years of brewing tensions between southern farmers and northern pastoralists, who migrated south due to climate-induced desertification, suddenly erupted into armed conflict in Benue, Nasarawa, and Plateau states of Nigeria in 2018, the people, including previously displaced, were forced to leave their homes [40].

However, people often choose to stay when they have appropriate location-specific and social capital, government support, and household- and community-level adaptation strategies to rebuild and conserve. Not only this, but an individual’s demography—such as age, gender, marital status, and psychological factors regarding the sense of place and perception of risks—also plays a role in migration decisions [124-129].

Conclusion

Research on environmental migration was initially concentrated on showing migration as a measure of Earth’s deteriorating conditions as a human living habitat. Environmentalists’ broad estimate of environmental migrants based on a deterministic approach drew critical responses. Researchers and migration scholars argue that environmental changes are a contextual factor and trigger migration only when intertwined with other divers of migration. Moreover, migration outcomes, either no or out or return, are a function of the aggregated adaptive capacity of actors at all scales.

On the macro- and meso-scales, disaster preparedness, relief, and recovery efforts play a significant role, while on the microscale, household economic capital, demographic composition, location-specific capital, sense of place, social resources, and adaptation strategies determine whether households stay or move during climate events. While there may be disparities between environmentalists and migration scholars, both agree that migration is one of the many adaptive strategies for vulnerable people living in climate-stress areas with scant livelihood diversification options.

Based on real-life studies, this paper presented the Environment-Migration Nexus Framework that highlights how various multifaceted factors impact migration decisions. The framework explicitly states the impacts of rapid and slow-onset disasters in a location, thereby increasing people’s vulnerability. In such circumstances, migration decisions are largely influenced by individual factors, location-specific capital, the government supports, and household- and community-level adaptation strategies. The framework might provide the researchers in this field with a more accurate and broader picture of migration in the context of an environmental stressor or climate change.

References

- Ming A, Rowell I, Lewin S, Rouse R, Aubry T, Boland E (2021) Key messages from the IPCC AR6 climate science report. Cambridge Open Engage.

- Dodd RJ, Chadwick DR, Harris IM, Hines A, Hollis D, et al. (2021) Spatial co‐localisation of extreme weather events: a clear and present danger. Ecology Letters 24(1): 60-72.

- Rigaud KK, de Sherbinin A, Jones B, Bergmann J, Clement V, et al. (2018) Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Singh C, Basu R (2020) Moving in and out of vulnerability: Interrogating migration as an adaptation strategy along a rural–urban continuum in India. The Geographical Journal 186(1): 87-102.

- Cattaneo C, Beine M, Fröhlich CJ, Kniveton D, Martinez-Zarzoso I, et al. (2019) Human migration in the era of climate change. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13(2).

- Wiederkehr C, Beckmann M, Hermans K (2018) Environmental change, adaptation strategies and the relevance of migration in Sub-Saharan drylands. Environmental Research Letters 13(11): 113003.

- EEA (2017) Climate Change, Impacts, and Vulnerability in Europe 2016: An Indicator based report. European Environment Agency (EEA).

- Myers N (2002) Environmental refugees: a growing phenomenon of the 21st Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 357(1420): 609-613.

- Cundill G, Singh C, Adger WN, De Campos RS, Vincent K, et al. (2021) Toward a climate mobilities research agenda: Intersectionality, immobility, and policy responses. Global Environmental Change 69: 102315.

- McLeman R, Gemenne F (2018) Environmental migration research: Evolution and current state of the science. Routledge handbook of environmental displacement and migration 3-16.

- Black R, Adger NW, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, et al. (2011) The Effect of Environmental Change on Human Migration. Global Environment Change 21(1): S3-S11.

- El-Hinnawi E (1985) Environmental Refugees. UNEP.

- Jacobson JL (1988) Environmental Refugees: A Yardstick of Habituality. SAGE Journals 8(3): 257-258.

- Boano C, Zetter R, Morris T (2008) Environmentally displaced people: understanding the linkages between environmental change, livelihoods and forced migration. Refugee Studies Center.

- Brown Oli (2008) The Number Games. In: Marion C, Maurice H. Climate Change and Displacement (pp. 8-9). Forced Migration Review.

- Sakdapolrak P, Naruchaikusol S, Ober K, Peth S, Porst L, et al. (2016) Migration in a changing climate. Towards a translocal social resilience approach. DIE ERDE–Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin 147(2): 81-94.

- Morrissey J (2009) Environmental Change and Forced Migration: A State of the Art Review. Oxford: Refugee Studies Center.

- Timmer A, Friedrich T (2016) Late Pleistocene Climate drivers of early human migration. Nature 538: 92-95.

- Gascoigne B (2001) History of Migration. History World.

- Cosmides L, Tooby J (2007) Evolutionary psychology: A primer.

- Tesfai M, DeGraaff J (2002) Participatory Rural Appraisal of Spate Irrigation Systems in Eastern Eritrea. Agriculture and Human Values 17(4): 359-370.

- Kelman I, Naess MW (2019) Climate Change and Migration for Scandinavian. Climate 7(4): 1-14.

- Freese J, Klement RJ, Ruiz-Núñez B, Schwarz S, Lötzerich H (2018) The sedentary (r)evolution: Have we lost our metabolic flexibility? F1000Res, 6(12724.2).

- Myers N, Kent J (1995) Environmental Exodus: An Emergent Crisis in the Global Arena. Washington D.C.: Climate Institute, United States.

- Kelman I (2019) Imaginary numbers of climate change migrants?. Social Sciences 8(5): 131.

- Laan AJ (2021) Climate Security Discourse in the UN Security Council: Echoes of Malthus? (Master's thesis).

- Hendrixson A, Hartmann B (2019) Threats and burdens: Challenging scarcity-driven narratives of “overpopulation”. Geoforum 101: 250-259.

- Bettini G (2013) Climate barbarians at the gate? A critique of apocalyptic narratives on ‘climate refugees’. Geoforum 45: 63-72.

- Gemenne F (2011) Why the numbers don’t add up: A review of estimates and predictions of people displaced by environmental changes. Global Environmental Change 21(1): S41-S49.

- Warner K, Hamza M, Oliver-Smith A, Renaud F, Julca A (2010) Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Natural Hazards 55(3): 689-715.

- Lukyanets A, Ryazantsev S, Moiseeva E, Manshin R (2020) The economic and social consequences of environmental migration in the central Asian countries. Central Asia and the Caucasus 21(2): 142-156.

- Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Beagley J, et al. (2021) The 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. The Lancet 397(10269): 129-170.

- Ajibade I, Sullivan M, Haeffner M (2020) Why climate migration is not managed retreat: six justifications. Global Environmental Change 65: 102187.

- Norwegian Refugee Council (2009) Climate Changed: People Displaced. Oslo: Norwegian Refugee Council.

- Biermann F, Boas I (2010) Preparing for a warmer world: Towards a global governance system to protect climate refugees. Global environmental politics 10(1): 60-88.

- Global Humanitarian Forum (2009) The Anatomy of a Silent Crisis. Global Humanitarian Forum Geneva.

- Stern N (2007) The Economics of Climate Change: the Stern review. Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom.

- Safra de Campos R, Codjoe SN A, Adger WN, Mortreux C, Hazra S, et al. (2020) Where people live and move in deltas. In Deltas in the Anthropocene (pp. 153-177). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Vigdor J (2008) The Economic Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(4): 135-154.

- IDMC (2019) Global Report on Internal Displacement 2019. Nowregian Refugee Council.

- Tower A (2017) Shrinking options: the nexus between climate change, displacement and security in the Chad river basin. Climate Refugees.

- McLeman RA (2014) Climate and Human Migration. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Wissink M, Düvell F, Mazzucato V (2020) The evolution of migration trajectories of sub-Saharan African migrants in Turkey and Greece: The role of changing social networks and critical events. Geoforum, 116: 282-291.

- Hunter LM, Luna JK, Norton RM (2015) The environmental dimensions of migration. Annual Review of Sociology 41: 377-397.

- Hunter LM, Nawrotzki R (2016) Migration and the environment. International handbook of migration and population distribution 465-484.

- Wickramasinghe AA IN, Wimalaratana W (2016) International migration and migration theories. Social Affairs 1(5): 13-32.

- Hagen‐Zanker J (2008) Why do people migrate? A review of the theoretical literature. A Review of the Theoretical Literature. Maastrcht Graduate School of Governance. Working Paper No.2008/WP002

- Faist T (2021) The crucial meso-level. In International migration, immobility and development (pp. 187-217). Routledge.

- Rogov M, Rozenblat C (2018) Urban resilience discourse analysis: towards a multi-level approach to cities. Sustainability 10(12): 4431.

- Lucini B (2014) Multicultural approaches to disaster and cultural resilience. How to consider them to improve disaster management and prevention: the Italian case of two earthquakes. Procedia Economics and Finance 18: 151-156.

- Copper R (2018) Hurricane Florence Recovery Recommendations. Raleigh: Office of the Governor: State of North Carolina.

- Cobler P (2018) Federal Government Approves Texas Plan of Long-term Harvey Recovery Funds. The Texas Tribune.

- Government of Kentucky (2022) Gov Beshear Marks 6-Month Milestone in Tornado Recovery. Office of the Governor, Frankfort KY.

- Maharjan A, Prakash A, Gurung CG (2016) Migration and the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake in Nepal: Effect on Rescue and Relief Processes and Lessons for the Future. HI-AWARE. Working paper.

- UNOCHA (2019) After Cyclones Idai and Kenneth, Recovery in Mozambique Continues. Relief Web.

- IOM (2019) Mozambique Cyclone Ida and Cyclone Kenneth Response: Situation Report # 13. IOM, UNI Migration.

- Wasike A (2017) Kenya drought: Various forms of aid provide relief. Made for Minds.

- USAID (2017) Horn of Africa - Complex Emergency. USAID.

- Kafle SK (2011) Measuring disaster-resilient communities: A case study of coastal communities in Indonesia. Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning 5(4): 316-327.

- World Bank (2021) Investment in Disaster Risk Management in Europe Makes Economic Sense: Background Report. World Bank.

- Sharaan M, Iskander M, Udo K (2022) Coastal adaptation to Sea Level Rise: An overview of Egypt’s efforts. Ocean & Coastal Management 218: 106024.

- UNISDR (2012) How to Make Cities More Resilient: A Handbook for Local Government Leaders. Geneva: United Nations.

- UNISDR (2013) Building Resilience to Earthquakes in Chile. UNISDR Scientific and Technical Advisory Group.

- Aldrich DP, Page CM, Paul C (2016) Social Capital and Climate Change Adaptation. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science.

- Lotfata A, Ambinakudige S (2019) Natural disaster and vulnerability: An Analysis of the 2016 Flooding in Louisiana. Southeastern Geographer 59(2): 130-151.

- Kamal AM, Shamsudduha M, Ahmed B, Hassan SK, Islam MS, et al. (2018) Resilience to flash floods in wetland communities of northeastern Bangladesh. International journal of disaster risk reduction 31: 478-488.

- Cutter S, Boruff BJ, Shirley WL (2003) Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Social Science Quarterly 84(2): 242-261.

- Warner K, Afifi T, Henry K, Rawe T, Smith C, et al. (2012) Where the rain.

- Biswas B, Mallick B (2021) Livelihood diversification as key to long-term non-migration: evidence from coastal Bangladesh. Environment, Development and Sustainability 23(6): 8924-8948.

- Zickgraf C (2018) Immobility. In Routledge handbook of environmental displacement and migration. Routledge, (pp. 71-84)..

- Nawrotzki R, DeWaard J (2017) Putting Trapped Populations into Place: Climate Change and Inter-District Migration Flows in Zambia. Regional Environmental Change 18(4): 1-14.

- Gray CL (2011) Soil Quality and Human Migration in Kenya and Uganda. Global Eviron Change 21(2): 421-430.

- McLeman R (2007) Household Access to Capital and its Influence on Climate Related Rural Population Change: Lesson from Dust Bowl Years. In: Wall E, Smit B, Wandel J (Ed.), Farming in a changing Climate: Agricultural Adaptation in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Curran SR, Meijer-Irons J (2014) Climate variability, land ownership and migration: evidence from Thailand about gender impacts. Washington journal of environmental law & policy 4(1): 37.

- Afifi T, Milan A, Etzold B, Schraven B, Rademacher-Schulz C, et al. (2016) Human mobility in response to rainfall variability: opportunities for migration as a successful adaptation strategy in eight case studies. Migration and Development 5(2): 254-274.

- Gray CL (2010) Gender, Natural Capital and Migration in the Southern Ecuadorian Andes. Environment and Planning A 42: 678-696.

- Olimova S, Olimov M (2012) Environmental Degradation, Migration, Internal Displacement, and Rural Vulnerabilities in Tajikistan. Dushanbe: International Organization for Migration (IOM).

- Jungehülsing J (2010) Women who go, women who stay: reactions to climate change. A Case Study on Migration and Gender in Chiapas.

- Alessandrini A, Ghio D, Migali S (2021) Population dynamics, climate change and variability in Western Africa: the case of Sahel regions.

- Roncoli C, Ingram K, Krishen P (2001) The Costs and Risks of Coping with Drought: Livelihood Impacts and Framers' Responses in Burkina Faso. Climate Research 19: 119-132.

- Phibbs S (2015) Disability Inclusive Disaster Preparedness and Response: The importance of social connectedness. UNISDR.

- Dun O (2011) Migration and Displacement Triggered by Floods in the Mekong Delta. International Migration 49(S21): e200-e223.

- Simms JR (2017) “Why Would I Live Anyplace Else?”: Resilience, Sense of Place, and Possibilities of Migration in Coastal Louisiana. Journal of Coastal Research 33(2): 408-420.

- Swapan MSH, Sadeque S (2021) Place attachment in natural hazard-prone areas and decision to relocate: Research review and agenda for developing countries. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 52: 101937.

- Qing C, Guo S, Deng X, Wang W, Song J, et al. (2022) Stay in Risk Area: Place Attachment, Efficacy Beliefs and Risk Coping. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(4): 2375.

- Blondin S (2021) Staying despite disaster risks: Place attachment, voluntary immobility, and adaptation in Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains. Geoforum 126: 290-301.

- Karunarathne AY, Lee G (2019) Traditional social capital and socioeconomic networks in response to flood disaster: A case study of rural areas in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 41: 101279.

- Kawamoto K, Kim K (2019) Efficiencies of bonding, bridging and linking social capital: Cleaning up after disasters in Japan. International Journal of disaster risk reduction 33: 64-73.

- Sanyal S, Routray JK (2016) Social capital for disaster risk reduction and management with empirical evidences from Sundarbans of India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 19: 101-111.

- Greon JA, Polivka AE (2010) Going Home after Hurricane Katrina: Determinants of Return Migration and Changes in Affected Areas. Demography 47(4): 821-844.

- Panday S, Rushton S, Karki J, Balen J, Barnes A (2021) The role of social capital in disaster resilience in remote communities after the 2015 Nepal earthquake. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 55: 102112.

- Tan‐Mullins M, Eadie P, Atienza ME (2021) Evolving social capital and networks in the post‐disaster rebuilding process: The case of Typhoon Yolanda. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 62(1): 56-71.

- Aldrich DP (2017) The Importance of Social Capital in Building Community Resilience. In: Yan W, Galloway W (eds) Rethinking Resilience, Adaptation and Transformation in a Time of Change. Springer, Cham.

- Aldrich DP (2012) Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- IFRC (2018) Case Studies: Red Cross Red Crescent Disaster Risk Reduction in Action-What works at local level. Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

- IPCC (2012) Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Antwi-Agyei P, Nyantakyi-Frimpong H (2021) Evidence of climate change coping and adaptation practices by smallholder farmers in northern Ghana. Sustainability 13(3): 1308.

- Ahmed Z, Guha GS, Shew AM, Alam GM (2021) Climate change risk perceptions and agricultural adaptation strategies in vulnerable riverine char islands of Bangladesh. Land use policy 103: 105295.

- Thalheimer L, Otto F, Abele S (2021) Deciphering impacts and human responses to a changing climate in East Africa. Frontiers in Climate 3: 692114.

- Schutte S, Vestby J, Carling J, Buhaug H (2021) Climatic conditions are weak predictors of asylum migration. Nature communications 12(1): 1-10.

- Burzyński M, Deuster C, Docquier F, De Melo J (2019) Climate Change, Inequality, and Human Migration. Journal of the European Economic Association 20(3): 1145-1197.

- Abel GJ, Brottrager M, Cuaresma JC, Muttarak R (2019) Climate, conflict, and forced migration. Global environmental change 54: 239-249.

- Massey DS (2020) Immigration policy mismatches and counterproductive outcomes: unauthorized migration to the US in two eras. Comparative Migration Studies 8(1): 1-27.

- Zickgraf C (2019) Climate change and migration crisis in Africa. The Oxford handbook of migration crises, 347.

- Beine M, Parsons CR (2017) Climatic factors as determinants of international migration: Redux. CESifo Economic Studies 63(4): 386-402.

- Zickgraf C (2021) Climate change, slow onset events and human mobility: reviewing the evidence. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 50: 21-30.

- Kaczan DJ, Orgill-Meyer J (2020) The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights. Climatic Change 158(3): 281-300.

- Berlemann M, Tran TX (2021) Tropical Storms and Temporary Migration in Vietnam. Population and Development Review 47(4): 1107-1142.

- Oakes R, Milan A, Campbell J (2016) Kiribati: Climate change and migration-Relationships between household vulnerability, human mobility and climate change.

- Chumky T, Basu M, Onitsuka K, Parvin GA, Hoshino S (2022) Disaster-induced migration types and patterns, drivers, and impact: A Union-level study in Bangladesh. World Development Sustainability 1:100013.

- Baez J, Caruso G, Mueller V, Niu C (2017) Droughts augment youth migration in Northern Latin America and the Caribbean. Climatic change 140(3): 423-435.

- Didenko I, Volik K, Vasylieva T, Lyeonov S, Antoniuk N (2021) Environmental migration and country security: Theoretical analysis and empirical research. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 234, p. 00010). EDP Sciences.

- Pajaron MC, Vasquez GNA (2020) Weathering the storm: weather shocks and international labor migration from the Philippines. Journal of Population Economics 33(4): 1419-1461.

- Murakami E (2020) Climate change and international migration: Evidence from Tajikistan (No. 1210). ADBI Working Paper Series.

- Shakya S, Basnet S, Paudel J (2022) Natural disasters and labor migration: Evidence from Nepal’s earthquake. World Development 151: 105748.

- UNICEF (2018) Mexico Earthquakes Humanitarian Situation Report: Six Month Review. UNICEF.

- IDMC (2020) Global Report on Internal Displacement 2020. Nowregian Refugee Council.

- IDMC (2021) Global Report on Internal Displacement 2021. Nowregian Refugee Council.

- Coalson JE, Anderson EJ, Santos EM, Madera Garcia V, Romine JK, et al. (2021) The complex epidemiological relationship between flooding events and human outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases: a scoping review. Environmental health perspectives 129(9): 096002.

- McMichael C (2015) Climate change-related migration and infectious disease. Virulence 6(6): 548-553.

- Watson JT, Gayer M, Connolly MA (2007) Epidemics after natural disasters. Emerging infectious diseases 13(1).

- Harris LM (2021) Everyday experiences of water insecurity: Insights from underserved areas of Accra, Ghana. Dædalus 150(4): 64-84.

- Raleigh C (2010) Political marginalization, climate change, and conflict in African Sahel states. International studies review 12(1): 69-86.

- Aldrich DP (2010) Fixing Recovery: Social Capital in Post-Crisis Resilience. Journal of Homeland Security.

- Cohen-Salgado D, García-Frapolli E, Mora F, Crick F (2021) How does social capital shape the response to environmental disturbances at the local level? Evidence from case studies in Mexico. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 52: 101951

- falls : climate change, food and livelihood security, and migration. UNU-EHS.

- UNHCR (2021) Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2021. UNHCR-The UN Refugee Agency.

- Wallerstein I (1976) The Modern World System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. Academic Press, New York.

- Wolpert J (1965) Behavioral Aspects of the Decision to Migrate. Papers of the Regional Science Association 15: 159-169.