Higher ratios of face to face blended learning is positively related to student satisfaction

Michael Seredycz*

Department of Sociology, MacEwan University, Canada

Submission: March 09, 2021; Published: March 30, 2021

*Corresponding author: Michael Seredycz, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, MacEwan University, 10700 104th Avenue Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

How to cite this article:Michael S.Higher ratios of face to face blended learning is positively related to student satisfaction. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2021; 6(3): 555686. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2021.06.555686

Abstract

This study investigated the satisfaction of 303 undergraduate students who enrolled in traditional 200-level criminology/ criminal justice courses. University students were offered the opportunity to self–select into one of four blended online ratios ranging from 10%, 30% 70% to 90% of the course operating within an online environment. OLS linear regression analysis suggests that students who selected lower intervals of online blended instruction (or high intervals of F2F instruction) were statistically more likely to report higher levels of overall satisfaction in the course. Alternatively, the findings suggest that higher ratios of student selected online instruction may lead to higher levels of student dissatisfaction. OLS data findings reported that younger university students who require more flexibility and convenience of scheduling, are enrolled in higher course loads and/or majoring or minoring in the subject matter produced statistically higher levels of student satisfaction.

Keywords:Online; Blended; Hybrid; Face to Face; F2F; Student Satisfaction; Learner-Content; Learner-Instructor; Learner-Learner; Learner-Technology; Interaction; Student Satisfaction Survey

Introduction

In the current COVID19 pandemic environment [1], post-secondary academic institutions and instructors are scrambling for a best practices model to continue to teach their students. Additionally, the university student (or consumer) searches for the instructional delivery that suits their needs and priorities. With the increasing cost of living, expectation of employment, travel, tuition and textbooks, students are consciously re-assessing the value for their dollar to determine which institution is right for them. We know when universities offer the availability of online and blended courses [2] as well as flexibility in scheduling [3,4] students prefer and are likely more satisfied with their courses [4]. Blended learning offers a solution to traditional face to face lecture contact, combining technology with interval levels of face to face instruction.

It certainly appears that undergraduate students as consumers of educational attainment want more choice and selection of course instruction, not less. As consumers of learning, student satisfaction needs to be accounted for. As Brooks [5] suggests, a significant majority (83%) of students preferred some form of blended instruction rather than a traditional face to face (10%) or traditional online (7%) course. The Center for Applied Research also reports that prefer digital mediums, that device ownership (tablets, smartphones, tablets) is greater among students than the public marketplace and students view their technology as important to their education and success (2016:5). The use of technology within an online environment appears to breed a form of success and/or satisfaction not found within traditional face to face courses. This study explores the use of interval/ ratio levels of student self-selection of course delivery to determine if/ and at what ratios of blended course delivery impacts overall reported student satisfaction.

Literature review

Student satisfaction can be conceptualized using a variety of indices from objective performance measurements assessing grade attainment to subjective measures of student attitudes on process- based learning and its efficacy [6]. Student satisfaction surveys have been numerous and rely on similar questions [7]. As a result, many satisfaction surveys probe the interactions learners have with one another, their instructor, course content, online technology and the method by which it is delivered [8]. There is ample research to suggest that blended learning instruction can impact student satisfaction. Blended learning generally offers differing environments that connect traditional lectures with some form of online learning [10]. A meta-analysis by Moskal et al. [10] examined the adoption of blended learning to its implementation and outcomes. The study reported higher levels of satisfaction among students who enrolled in blended courses versus fully online or lecture-based modes of instruction [10]. Research suggests that even if there may be no difference within instructional delivery, students still prefer blended learning. Owston et al. [11] found similar levels of satisfaction when students were asked to compare their blended course instructional delivery to other traditional courses they previously had taken; almost 70% of students reported they would take a blended course again. This was also confirmed by Madriz and Nocente (2016) who surveyed nearly 600 undergraduate students finding overall levels of satisfaction were higher among blended learning and student’s willingness to take another blended course. Vernadakis et al. [12] compared blended and face to face (F2F) sections and found that students enrolled in blended sections reported significantly higher satisfaction (conceptualized from a twelve-question survey). Forte and Root (2011) reported similar findings in which students who enrolled in a blended format had higher levels of satisfaction versus traditional courses with some levels of web-enhancement. Melton et al. [13] compared the satisfaction of students enrolled in four general health courses finding that satisfaction scores were statistically higher for those students enrolled in three blended learning courses than one traditional F2F course. Therefore, there appears to be significant advantages for students when employing a blended learning method to their course load. A study conducted by Dziuban et al. [14, 15] reported higher levels of student satisfaction in a variety of blended courses with 85% of students agreeing that they were satisfied and 67% reporting they would like to take another blended course. Utilizing both blended and F2F instructional delivery within a nursing student population, Kumrow (2007) found that blended students were more satisfied than unsatisfied. These studies have all implied that there is an importance of learning independently outside of the classroom which has positive impacts on satisfaction, grades and future expectations for blended courses [16]. The question may not be why an instructor may implement blended learning, but rather why wouldn’t an instructor consider this blending learning opportunity. Student satisfaction includes inherent factors which are often difficult to operationalize such as the motivation to taking a course to a student’s level of pleasure throughout the course to the effectiveness of the educational experience (Wang, 2003). Wu et al. (2008) suggest that higher levels of student satisfaction within a blended learning approach is due to a student’s perceived ease of use, value of the content and the climate or environment itself (for involvement and social interaction). Further research by Wu and Liu (2013) confirmed that perceived ease of use is positively correlated with student satisfaction. Sahin and Shelley [17] suggest, it is not just ease of use but also the value and usefulness of the content (similar to any traditional F2F or fully online course). Therefore, each instructor’s inherent design, organization, choice and ease of software implementation and adoption (or lack thereof) of content and value within performance measures can impact student satisfaction. As such, the value of learning interactions and outcomes can often be associated not just with student satisfaction but also the choices instructors make when selecting software and organizing a course. This best reflects what we know in blended learning. While blended learning appears to offer significant value and benefits to students, choices instructors make should ensure that there is an ease and proficiency of use of software within course delivery is paramount to ensuring student success and/or satisfaction. Should students not be proficient in the software and/or frustrated with the layout of the course design, satisfaction may wane. Therefore, student success and satisfaction can closely be tied to the design of the blended course.

The design and implementation of blended instruction requires a thoughtful approach to content, the technology being utilized and performance measurements [18,19]. Some studies offer quality assurance checklists to assist instructors (Chauhan et al., 2016) however, there is no uniform one size fits all strategy. Therefore, instructors need to ensure that new online learning environments are designed appropriately for their targeted audience while also meeting the needs and expectations of students [17]. Due to the holistic and individualized approach to the adoption, development and implementation of courses (not just blended), it creates a level of difficulty and uncertainty in ascertaining what blending works, with which student populations and whether these courses can even be compared to traditional F2F or fully online courses. As meta-analyses of studies have identified, there is a lack of matched or equivocal groups of students to make often generalizable comparisons between blended, traditional face to face and online courses [6,16,20]. As such, there are limitations to simply suggesting that blended learning, as a one size fits all strategy will be effective. Satisfaction is often measured conceptually or operationally differently across studies which can lead to mixed results. Other studies have proposed that success be measured in terms of mean/average disparities of grades between groups of students but perhaps the performance measurements in the courses were different. Some studies lack more rigorous testing to examine correlations and/or relationships. As such, there are limitations in asserting that blended learning is simply better than traditional face to face or online learning instruction. This is not simply the fault of poor research methodologies but rather the lack of being able to randomly select students (for ethical reasons) and how university and college courses are offered/ distributed to instructors on an annual basis (leading to logistical issues). The lack of random sampling and selection, experimental designs and rigorous testing means that instructors and students should have a healthy level of skepticism of blended learning. Meta-analyses indicate promise in the adoption of blended learning but due to the lack of rigorous methodological approaches, there is no one perfect strategy on how to employ it [6,16,20]. An instructor’s selection of design and construction of blended learning within a course can and should be individualized to fit every instructor and student’s needs and priorities [22]. Therefore, there is not likely one specific percentage or interval that can be used to assert where blended learning is more successful than unsuccessful [23]. There does not appear to be a one size fits all ratio of blended instruction that will universally be effective [11]. Several studies and meta-analyses have reported similar findings where students prefer and/or rank blended course instruction over traditional face to face instructional delivery [20, 23] despite a lack of consensus of the appropriate ratios of blending. It should be noted that comparisons are often made between blended learning and traditional and/or online courses as if blended ratios were at a fixed ratio [10]. Despite these limitations, the evidence still supports the use of blended and online learning environments in that they can offer higher levels of student satisfaction than traditional face to face (F2F) instruction [16, 24]. This would suggest that there may be tipping points (for every instructor) when comparing success and satisfaction in and out of the classroom. As Shea et al. (2006) point out, having examined thirty-two colleges, an instructor’s teaching presence is positively related to a student’s sense of learning community and direct instructional facilitation. Therefore, while students may appreciate the convenience of hybrid/blended/independent time, that friendly face in the course is also likely a necessity when constructing a course that will ensure student satisfaction. A 2009 study by Morris and Lim examined the influence of instructional delivery and student learning interactions. Their findings suggest that in addition to age and prior experiences with distance learning opportunities impact students’ satisfaction; a student’s preference in delivery format and average study times are increasingly relevant factors in student satisfaction. This study suggests we need to consider other circumstantial and/or situational factors that are relevant to whether student satisfaction is attained - flexibility and convenience within a student’s life.

A 2016 government report reports that college and university students are working harder than ever before, where students are often taking full course loads (considered full time) while also employed either part or full time. Nearly half of students taking a full course load (41%) were currently employed either part or full time (Kena et al., 2016: 221). Of all students reporting, two in ten (18%) were employed 20-34 hours a week and one in ten students (7%) were working over 35 hours a week (Kena et al., 2016: 221). Therefore, flexibility is a significant need for a majority of students [10,11]. Owston et al. [11] found that students typically benefit from increased time and spatial flexibility during the delivery of their courses providing them more resources and autonomy to regulate their own learning. As Packham et al. [25] suggest, the causes of student failure in online courses are often attributed to issues of family, employment and management support. Therefore, providing more flexibility in time management has a significant impact on satisfaction [3, 26]. Therefore, generating an instructional delivery that facilitates choice and selection of blended learning may allow for higher levels of student success and/or satisfaction.

There is evidence to suggest that student selection of instructional format (when students are offered the opportunity to choose) may have an impact on student satisfaction. A study by Yatrakis and Simon [27] found that students who chose to enroll in courses within an online format achieve higher rates of satisfaction and a perceived retention of information than do students who enroll in online courses where no choice is provided. This concurs with the research of Debrourgh (1999) in that selfselection and satisfaction can be linked to a student’s retention of information. The findings of Yatrakis and Simon [27] suggest that students feel a greater degree of satisfaction when allowed to selfselect for online courses and that choice may carry over into their perception of retained information. These results can be used to support choice and self-selection as satisfying the preferences of the student consumer. This study explores the interval levels of student chosen instructional delivery on overall reported student satisfaction. While the majority of research points to selection being an advantageous option for students, other research [28] suggest a level of mixed results in whether instructional delivery has an impact on student satisfaction. Some studies have found no significant differences between the ratios of blended instructional delivery and satisfaction [29,30]. As such, this exploratory study seeks to add to the limited amount of research on student choice of blended instructional delivery and how other factors (explored above) impact on student satisfaction.

Methodology

This exploratory study examined students enrolled in seven undergraduate courses offered over a sixteen-week semester cycle. This was a convenient sample of students where no random selection existed. This is obviously a limitation but one that allowed student choice and selection of course instruction. Initially, there were 334 participants registered for the seven 200-level criminology/ criminal justice courses. Twenty-two students were removed from the study having dropped or withdrawn from the course throughout the semester. An additional nine students were removed from the study for not having completed survey instruments. Therefore, the sample size for the purpose of analysis was 303 participants. This study conceptualized and operationalized four blended delivery systems that students could select as developed by Twigg [31] and the Sloan Consortium [9]: (1) replacement (90% F2F:10% online); (2) supplemental (70% F2F:30% online) and two emporium options (3) 30% F2F:70% online and (4) 10% F2F:90% online. The most traditional offering was replacement delivery where 90% of the course would be face to face (F2F) and 10% within an online environment. As students considered transitioning away from face to face traditional mlectures, they could connect with one another and the instructor through the use of discussion boards and additional digital-based lectures (rather than F2F). Once a student had selected their desired blended instructional delivery, they could opt to revise this offering after the first exam (one month; 8 classes into the course). This offered each student more flexibility, an operational component of Twigg’s [31] buffet style approach Students were asked to complete several pre-test and post-test surveys which included Elaine Strachota’s Student Satisfaction Survey (2006) to ascertain satisfaction within each interval of student’s chosen blended learning which will be explored below. Each of the courses utilized a hard copy and/or digital textbook to ensure ease of access. Instructor developed Microsoft power point modules were used to supplement the textbook and offer additional resources and examples to ensure the retention of key concepts. Supplemental technical reports, peer reviewed articles and online open sourced audio-visual clips were also used to stimulate critical thinking and problem solving skills while ensuring overlap of important concepts and themes in the course. The course was rigorous in a sense that students would be asked to engage in significant reading and watching/viewing videos with a rigid structure/ schedule to ensure timelines were maintained and no additional time was offered for any groups of students being studied. The course was designed to ensure consistency across time, content and performance measurements [32]. Performance measures included three in-class examinations (75%) and three assignments (25%) with deadlines within the semester.

Findings

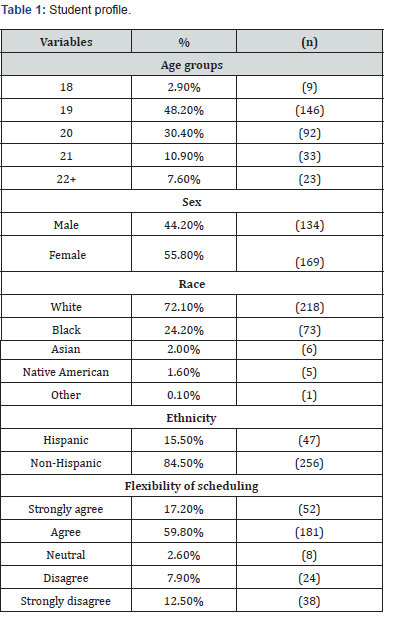

As explained previously, the study sample began with 334 eligible students enrolled in seven 200-level criminology/ criminal justice courses within a liberal arts university in the midwestern United States. Thirty-one students were removed from the study for (i) having dropped or withdrawing from the course or (ii) not completing their self-administered surveys. Therefore, 303 students were used for the analysis of this study. Students were asked to complete a short open-ended self-administered questionnaire at the beginning of the course. Responses were relevant to establishing a baseline of data points to understand the profile of the sample (Table 1 below). Table 1 provides a general demographic profile of the 303 students enrolled in the study. In terms of age distribution, a substantial majority (92%) of undergraduate students were aged 21 21 or under which would suggest that it would be typical of a traditional university 200-level course. Women represented a larger percentage (55%) of the students enrolled in the criminology/ criminal justice courses which mirrored the University’s student body demographics. The majority of students enrolled in courses self-identified as White (72%) and a large concentration of students self-identified as Black and/or African American (24%). Asian (2%) and Native American (1.6%) students were also well represented in the course, which closely resembled the student body population of the institution. The University campus in which these courses were facilitated in have a diverse population across it from large concentrations of Black and African American residents (16%) as well as Hispanic/ Latino residents (14%) which mirrored the student body populations of 21% and 15% respectively. Within this study, approximately 16% of the students self- identified as Hispanic and/or Latino. These demographic numbers on race and ethnicity would suggest that visible minorities were slightly oversampled in terms of their population in the area and within the student body population. While this may have an impact on results of the study, this profile of students was somewhat representative of the Institution’s student body. In an effort to test for student motivation and needs, the pre-test questions probed for students to reflect on whether flexibility and convenience (in time, travel to campus) was a factor for selecting a particular form of course instruction. A significant percentage of students enrolled in these courses agreed (60%) or strongly agreed (17%) that flexibility and convenience of scheduling impacted their decision on which ratio of blended learning instruction they would select. Approximately 3% of students reported a neutral response however, over 20% of students reported it would not affect their decision. This might suggest a number of factors that were not studied from whether a student was already on campus and felt more online instruction may not be useful, that a student’s schedule did or did not allow for revisions and whether this course should have been introduced to students with more advance warning could have impacted a student’s decision. These findings would substantiate the importance of flexibility and convenience that student’s require and perhaps why students may consider blended or online learning. However, as noted above, this was not an issue for nearly one in five students. Student profile data attained from pre-test surveys was also corroborated with a more rigorous and valid reporting measurements attained from the University Registrar. Table 2 examines the validation measurements that were used to also generate variables of interest for further predictive analysis.

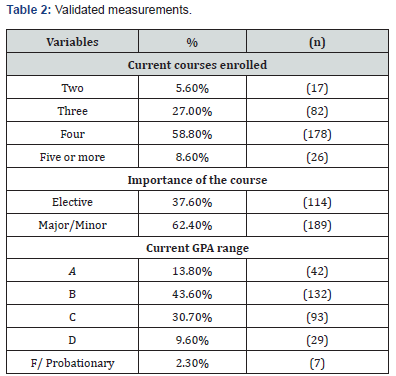

Within Table 2, undergraduate students enrolled in the seven criminology/ criminal justice courses were asked to provide their student number so that further variables (their current course load, their designated field of study and current grade point average) could be utilized as a more valid representation of their student history at the Institution. A significant percentage of students (94%) were currently enrolled in three or more classes, which is considered a full-time course load. Additionally, there were more students (8%) were taking the most courses allowed (without permission at five courses) than those students who were only taking two courses in the semester they were taking this course (7%). This finding would suggest that there were no students taking this course as their sole component of their university workload. This would suggest (not accounting for students who may be registered students at another university and the University where this study was conducted) that the findings identified in this study may be significantly different than those studies who may be unaware or not have controlled for course load. This is why the methodological approach within this (exploratory) study will likely generate unique findings that could be more consistent with traditional university students taking larger course loads than those students who are enrolled as part time or single course consumers.

The relative importance of the course was another variable of interest that is often not considered particularly pertinent or tested within the literature. Within this study, there was an expectation that undergraduate university students who are more likely to engage in a designated career path (in this case criminology/ criminal justice) may feel that face to face course work might be more ideal or are more motivated to take face to face courses versus students who enroll in the course to fill an elective within their liberal arts degree. This 200-level course was a pre-requisite for additional courses within the degree program and as such, a majority of the students (62%) had enrolled in these seven courses to fill that pre-requisite for their major/minor of study in criminology/ criminal justice. A smaller but still relatively large component of the students participating in this study (38%) had enrolled in the course either in fulfillment of their liberal arts degree requirement, as an elective and/or not having declared a major or minor in criminology/ criminal justice (which would have likely occurred prior to this course). This finding would suggest that there is still significant variance within the variable that the author felt could be a concern for further analysis. A final variable of interest that was validated through University records was a student’s cumulative grade point average (GPA), A student’s GPA would be compiled from their course work within the University and any other courses they may have transferred into from previous universities or colleges. This study purposely chose to use validated University records rather than selfreported scores from students as they would be more reliable and accurate considering that GPA is generally from a score of zero to a 4.0/4.5. Once a student’s GPA was coded, it was then categorized into University pre-determined values of an A, B, C, D and F and/or probationary status. Most students may characterize themselves as excellent however, a validated assessment of student GPA found that only 14% had attained a cumulative A average. The predominant number of students had attained a B (44%) and C (31%) cumulative GPA. Approximately one in ten students (12%) were considered at more high risk of poor or failing cumulative work. Obviously, the finding here is that a large majority of students had completed coursework in a good to fair job prior to enrolling in the course. As such, they may be inherently more likely to be satisfied with their previous work while also be very concerned with their grade in this course. Throughout the survey process, students were asked to select their mode of instructional delivery (viewed below).

Table 3 highlights the student self-selection and/or reselection of online instructional delivery within the seven criminology/ criminal justice courses. As viewed above, 45% of students preferred the 70:30 blended option of course instruction; where 70% of the course would be taught face to face (F2F) and 30% within an online environment. Approximately 2$% enrolled in a 10% online learning environment, similarly to 20% of students who selected a 70% online environment. Only 10% (31) of the 303 students selected an almost entirely 90% online environment. It should be noted that at no point in time, across all seven classes did any one student ever ask or want to select an option of 100% face to face. While this was not an option that students were offered, no one student even chose to ask. This in and of itself, was an interesting finding as there would be an expectation that if 20% of students who reported that convenience and flexibility was not an issue, that one of those students or perhaps other students who had performed well in traditional face to face courses may not want to change (and/ or choose to register/ enroll in this study). As explained within the methodology, to offer students additional flexibility and/or a choice, students were offered the opportunity to revise their initial blended course delivery. When provided this opportunity, 10 students revised their initial choice. This accounts for only 3% of all students. This would suggest that 97% of students were satisfied with their initial choice. Therefore, this study can infer that students appear to be confident in determining which level/ ratio/ interval of online instruction they favor. This might suggest that offering this option to traditionally based F2F courses may not require instructors to be overly concerned about student’s ease of access or uncertainty over their initial decision. Of the 10 students who revised their initial instructional delivery, each of these 10 students initially chose less face to face engagement (90:10 or 30:70). When asked to re-select their desired blended course instruction, 10 of 10 students re-selected options with more face to face interactions. Similar to the initial student selection process, no students wanted or preferred a re-imagined 100% face to face course. Operationalizing Twigg’s [31] classification of blended learning, a majority of undergraduate university students selected a replacement (25%) or supplemental approach (48%) rather than an emporium approach (26%). This finding suggests that students in this study preferred higher intervals of face to face instruction than higher ratios of online instruction. Reiterating what was mentioned previously, no one student sought out an entirely face to face traditional course which they originally enrolled in. These findings would infer that students did appreciate the opportunity to select their own instructional delivery. However, Might this appreciation have an impact on satisfaction?

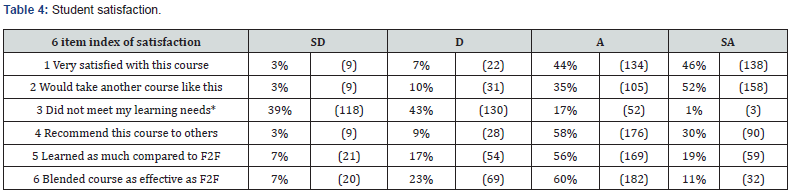

To assess student satisfaction, participating undergraduate students were asked to complete a follow-uo post-test survey once the course was complete and grades assigned. The six-item index of satisfaction was developed by Strachota [33] and further redesigned into what she coined as the Student Satisfaction Survey (2006). Table 4 highlights the findings of the general satisfaction of students within the sample. To pilot her survey instrument, Strachota [8] found this general satisfaction dimension had a reported.90 Chronbach alpha (ranging from zero to one) which is exceptional. The findings from Table 4 indicate that students enrolled in seven 200-level criminology/ criminal justice courses were very satisfied with the course utilizing Stachota’s general satisfaction survey (2006). Nine of ten students agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that they were very satisfied with the course while only 3% (9) of the 303 students reported being very dissatisfied with the course. Nearly the same percentage of students (87%) reported that they would take another selfselected blended instructional course again if it was offered. Further extrapolating the data, one in ten (12%) students reported that they would not recommend this course to others. When considering learning needs, there was significantly more variation in student responses. Approximately eight in ten students (82%) agreed or strongly agreed that the course met their learning needs with 18% reporting the course did not meet their learning needs. Three-quarters (75%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that they learned as much in this course (as compared to other face to face courses they had taken previously) [34-40]. Interestingly, 30% of students reported that they generally believed that blended courses would not be as effective as face to face courses. Therefore, the student responses to satisfaction in the course report some unusual and contradictory findings where students appear to have been very satisfied with the course, there were issues whether they would take another self-selected course (despite previous frequency distributions which inferred some level of appreciation) and/or whether the learning and instruction met their needs. It could be concluded that perhaps the instructor’s learning and/or instructional materials may not have matched the expectations of students. More research is certainly need to justify this potential inference. To assess and predict student satisfaction, an ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression was utilized for further analysis. As such, survey item/ statement three required a change in coding to ensure that each of the six item likert scales could be aggregated from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (3); within the appropriate direction. This allowed for the generation of a larger index of scores from 0-18. As seen in the frequency distributions above, there was enough variability in each of the variable to make conclusions about the potential relationship of that variable (age, sex, race, flexibility, course load, fulfillment of course credit, GPA and student choice of course instruction) and general satisfaction. Student self-selection was coded appropriately from low online instructional delivery to high) [41-50]. The OLS regression data is below.

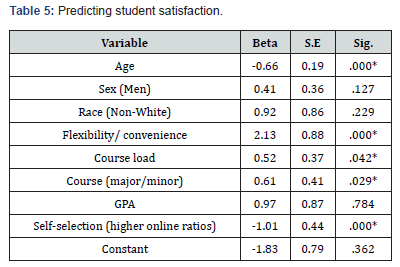

The linear regression model, located in Table 5, was found to be statistically significant (.001 with a confidence level of 95% with the p < .05 being significantly different than zero). Student self-selection and seven variables of interest were found to explain 48% of student satisfaction based on the Nagelkerke R Square (.482). The regression reported a Chi-square of 209.46 and a model -2 Log likelihood of 111.29 (with 8 degrees of freedom). Four cases were removed from the analysis when the variance inflation factor (VIF >4) and tolerance (TOL) levels of 2.0 or above were controlled for. Student self – selection of instructional delivery was found to be the second most important variable to predict student satisfaction. This finding would suggest that the lower the ratio of online blended learning, the higher the likelihood of student satisfaction. Put another way, the higher the percentage of independent or online learning within courses, the more likely students in this sample would be dissatisfied. This finding suggests that as interval levels of blended learning increase, it can have a detrimental effect on student satisfaction. This might suggest that not all blended learning is the same and that there may be tipping points where satisfaction may become dissatisfaction. However, it should be noted that student choice of instructional delivery was not the only statistically significant variable within the model (based on the Beta values) [51-59].

The most significant predictor of the course satisfaction regression model was the flexibility and convenience of the course offerings. This is consistent with previous research in the field in that blended learning courses can predict student satisfaction. This suggests that not only is flexibility important in scheduling but additionally, that those students who enroll in more courses within a semester are more likely to be satisfied than students who enroll in lower numbers of courses simultaneously. The evidence, supported by the data, suggests that age was also a predictor of satisfaction. It appears that older students who participated in the study were more likely than younger adults to be dissatisfied with the course. This is somewhat surprising as it could be hypothesized that older students may be more likely to require more flexibility and convenience (due to employment, child care, etc.). However, this could be a case where ease of use (as explored in the literature) may have been an impact variable rather than age. Other demographic variables including sex and race were found to not have any statistical significance within the model. This is consistent with some of the research findings [16]. Students with higher course loads appeared to be more satisfied with the course. This could be due to the opportunity to have a more balanced and/or flexible schedule however, it is more likely that attaining more course independent time to complete work and assignments had an impact. However, more research is needed before this can be verified but it is certainly an interesting finding. A finding not often examined in the research is whether student interest or motivation, as denoted by a student’s major or minor level of study, has an impact on their reported satisfaction. The data suggests that students who had declared a major or minor in the study of criminology/ criminal justice were more likely to be satisfied with the 200-level criminology/ criminal justice course they enrolled in. Therefore, students who utilized this course as an elective for their liberal arts degree were less likely to be satisfied with the course. This might suggest that how the instructor constructed this course may have inherently benefitted students who declared a major or minor in the field of interest versus those who may have had less interest in the course content. Obviously more research is necessary to understand how student motivation impacts satisfaction.

Implications

As an exploratory case study, the findings of this research would suggest that more examination of blended learning and intervals/ratios of blended learning need to be examined. Simply offering blended learning does not have an impact on course satisfaction (as all forms of instructional delivery in this study had some form of online delivery). This would suggest that there is a tipping point where students find satisfaction with the blended offering but too much blended learning (using the instructional delivery explained within the methods section) has an inverse relationship to student satisfaction. This study finds that student selected ratios or intervals of blended learning that offer more face to face interaction rather than less result in higher levels of student satisfaction. This finding would certainly suggest that while students appreciate the convenience and flexibility of hybrid and blended instruction, they still want (in this instructor’s course) face to face interactions. Therefore, when constructing courses, instructors should be diligent to ensure that they are present and that students receive that face to face time (that even digital recordings are unable to capture). That rapport and relationship building appears to be important to student satisfaction in this study (however more in-depth research is needed). However, as expressed in the literature review, there is no perfect one size fits all strategy to implement blended learning as each instructor will construct their own course, based on their needs and the needs of their students.

As referenced in the literature, convenience and flexibility remains a significant factor when understanding the circumstances students face and satisfaction within their courses. This also may hold true for instructors as well. With a relatively good variance explained within the model, there appears to be hope on the horizon that the use of this a consistent construction and design of a course could reap benefits with instructors and students alike (without significant revision each year). While more research is needed to identify more conclusive findings, blended learning is an increasingly attractive alternative to traditional face to face or online learning and has a significant impact on a student’s or consumer’s satisfaction particularly post-COVID-19. As students continue to search their desired instructional delivery it would be wise that instructors consider offering more choice and selection to ensure each student can attain their desired learning interactions within the same class based on their motivations. Allowing student self-selection also might alleviate the finding that with more online instruction, Allowing student discretion to make their instructional delivery selection places more emphasis on their decision making rather than potentially blaming one form of instructional delivery over another. Despite these findings, it is clear that more research is needed on intervals of blended learning, stronger comparison groups and how student selection impacts not simply student satisfaction but also grade attainment and/or other measures of student success.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) ITU-WHO Joint Statement: Unleashing Information Technology to defeat COVID-19. Press Statement.

- Simon H, Yatrakis P (2002) The Effect of Self-selection on Student Satisfaction and Performance in Online Classes. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 3(2).

- Cooper L (2001) A Comparison of Online and Traditional Computer Applications Classes. THE, 28(8): 52 - 58.

- Bernard R, Abrami, Yiping Lou, Evgueni Borokhovski, Anne Wade (2004) How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research 74(3): 379-439.

- Brooks D (2016) ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology 2016. Louisville, CO: ECAR.

- Hill T, et al. (2013) A Field Experiment in Blended Learning. Performance Effects of Supplementing the Traditional Classroom Experience with a Web-based Virtual Learning Environment in AMCIS 2013 Proceedings.

- Kuo Y, et al. (2013) A predictive study of student satisfaction in online education programs. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 14(1): 16-39.

- Strachota E (2006) The use of survey research to measure student satisfaction in online courses. Presented at the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, University of Missouri-St. Louis, MO, United States.

- Allen I, Seamon J (2013) Changing course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. Needham, MA: The Sloan Consortium.

- Moskal P, Charles Dziuban, Joel Hartman (2013) Blended learning: A dangerous idea? The Internet and Higher Education, 18: 15-23.

- Owston R, York D (2018) The nagging question when designing blended courses: Does the proportion of time devoted to online activities matter? Internet and Higher Education 36: 22-32.

- Vernadakis N, Giannousi Maria, Tsitskari Efi, Antoniou Panagiotis, Kioumourtzoglou Efthimis (2012) Comparison of student satisfaction between traditional and blended technology course offerings in Physical education. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 13(1): 137-147.

- Melton B, et al. (2009) Achievement and Satisfaction in Blended Learning versus Traditional General Health Course Designs. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 3(1): 1-13.

- Dziuban, C, et al. (2005) Higher education, blended learning, and the generations: Knowledge is Power - No more in J. Bourne and J. Moore Ed., Elements of quality online education: engaging communities. Needham, MA: Sloan Consortium for Online Education.

- Dziuban C, et al. (2007) Student satisfaction with asynchronous learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1): 87-95.

- Means, B. et al. (2013) The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta–analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record 115(3): 1-47.

- Chang S, Smith R (2008) Effectiveness of personal interaction in a learner-centered paradigm distance education class based on student satisfaction. Journal of Research on Technology in Education 40(4): 407-426.

- Garrison D, Kanuka H (2004) Blended learning: uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet and Higher Education 7(2): 95-105.

- Garrison D, Anderson T (2003) E-Learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice. Routledge/Falmer, London, UK.

- Moskal P, et al. (2006) Peer Review: Emerging trends and key debates in undergraduate education. Learning and Technology, 8(4).

- Drysdale J, Charles Graham R, Kristian Spring J, Lisa Halverson R (2013) An analysis of research trends in dissertations and theses studying blended learning. Internet and Higher Education 17: 90-100

- Allen I et al. (2007) Blending in: The extent and promise of blended education in the United States. Sloan Consortium.

- Spanjers I, Karen Könings D, Jimmie Leppink, Daniëlle ML Verstegen, et al. (2015) The promised land of blended learning: Quizzes as a moderator. Educational Research Review, 15: 59-74.

- Picciano A, Seaman J (2007) K-12 online learning: A survey of U.S. school district administrators. Sloan Consortium, New York, USA.

- Packham G et al (2004) E-learning and retention: key factors influencing student withdrawal. Education and Training, 46(6-7): 335-342.

- Garrison D (2009) Communities of inquiry in online learning: Social, teaching and cognitive presence. In Howard C, et al. 2nd, Encyclopedia of distance and online learning. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 352-355.

- Yatrakis P, Simon H (2002) The effect of self-selection on student satisfaction and performance in online classes. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 3(2): 1-8.

- Larson D, Chung-Hsien S (2009) Comparing student performance: online versus blended versus face-to-face. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 13(1): 31-42.

- Stizman T, Kurt Kraiger, David Stewart, Robert Wisher (2006) The comparative effectiveness of web-based and classroom instruction: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology 59(3): 623-664.

- Zhang D et al. (2004) Can e-learning replace classroom learning? Communications of the ACM 47(5): 75-79.

- Twigg C (2003) Improving learning and reducing costs: New models for online learning. Educause Review, 38(5): 28-38.

- McGee P, Reis A (2012) Blended course design: A synthesis of best practices. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 16(4): 7-22.

- Strachota E (2003) Student satisfaction in online courses: An analysis of the impact of learner-content, learner-instructor, learner-learner and learner-technology interaction. Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Ann Arbor, Michigan, UMI Publishing.

- Allen I, Seaman J (2010) Class Differences: Online Education in the United States, 2010. Needham, MA: The Sloan Consortium, 1-26.

- Anderson T, Liam Rourke, Randy Garrison, Walter Archer (2001) Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2).

- Akyol Z, et al. (2009) Online and blended communities of inquiry: Exploring the developmental and perceptional differences. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 10(6): 65-83.

- Anderson T (2004) Theory and Practice of Online Learning. AU Press, Athabasca University, Canada.

- Carr S (2001) Is anyone making money on distance education? Chronicle of Higher Education, 47(23): 41.

- Cassidy S, Eachus P (2002) Developing the computer user self efficacy (CUSE) scale: Investigating the relationship between computer self efficacy, gender and experience with computers. Journal of Educational Computing Research 26(2): 133-153.

- Colachico D (2007) Developing a sense of community in an online environment. International Journal of Learning 14(1): 161-165.

- Duffy T, Kirkley J (2004) Learner centered theory and practice in distance education: Cases from higher education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ferguson J, DeFelice A (2010) Length of online courses and student satisfaction, Perceived learning and academic performance. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 11(2): 73-84.

- Garrison D, Terry Anderson, Walter Archer (1999) Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education 2(2): 87-105.

- Harden R (2002) Myths and e-learning. Medical Teacher 24(5): 469-472.

- Kirkley J, et al. (2001) Supporting pre K-12 teachers in designing online, inquiry-based instruction. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of American Educational Research Association, Seattle, WA.

- Koh E, Lim J (2012) Using online collaboration applications for group assignments: The interplay between design and human characteristics. Computers and Education 59(2): 481-496.

- Kumerow A, Marcia Miller, Rhonda Reed (2012) Baccalaureate courses for nurses online and on campus: A comparison of learning outcomes. American Journal of Distance Education 26(1): 50-65.

- Kurucay M, Inan F (2017) Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Computers and Education 115: 20-37.

- Kwak D, et al. (2013) Assessing the impact of blended learning on student performance. Educational Technology and Society 15(1): 127–136.

- Lim D, Morris M (2009) Learner and Instructional Factors Influencing Learning Outcomes within a Blended Learning Environment. Educational Technology and Society 12(4): 282-293.

- Lim D, Morris Michael L, Kupritz Virginia W, (2007) Online vs. blended learning: Differences in instructional outcomes and learner satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 11(2): 27-42.

- Moore M, Kearsley G (2005, 1996) Distance education: A system view. Belmont, Thomson-Wadsworth, CA, United States.

- Piccoli G, Rami Ahmad, Blake Ives (2001) Web-based virtual learning environments: a research framework and a preliminary assessment of effectiveness in basic IT skill training. MIS Quarterly 25(4): 401-426.

- Rovai A (2002) Sense of community perceived cognitive learning, and persistence in asynchronous learning networks. The Internet and Higher Education 5(4): 319-332.

- Rovai A, Barnum K (2003) Online course effectiveness: An analysis of student interactions and perceptions of learning. Journal of Distance Education 18: 57-73.

- Sher A (2009) Assessing the relationship of student-instructor and student-student interaction to student learning and satisfaction in Web-based online learning environment. Journal of Interactive Online Learning 8(2): 102-120.

- Summers J, Alexander Waigandt, Tiffany Whittakeret A (2005) A Comparison of Student Achievement and Satisfaction in an Online Versus Traditional Face to Face Statistics Class. Innovative Higher Education 29(3): 233-250.

- Wai C, Seng E (2015) Measuring the effectiveness of blended learning environment: A case study in Malaysia. Education and Information Technologies 20(3): 429-443.

- Zhao Y, Breslow L (2013) Literature review on Hybrid/ Blended Learning. Teaching and Learning Laboratory. Cambridge, MA: MIT.