Alliances and COVID-19: An Alliance- Shock Response Framework

Brian Tjemkes* and Peter Simoons

Associate Professor Strategy & Organization, Department of Management & Organization, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands

Submission: February 9, 2021;Published: February 22, 2021

*Corresponding author: Brian Tjemkes, Associate Professor Strategy & Organization, Department of Management & Organization, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1105, 1081HV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

How to cite this article: Tjemkes BV, Simoons P. Alliances and COVID-19: An Alliance-Shock Response Framework. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2021; 6(2): 555683. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2021.06.555683

Abstract

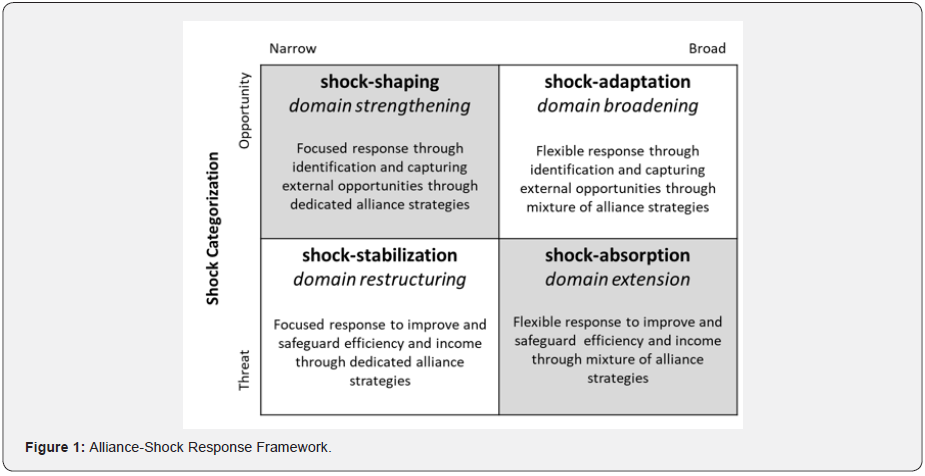

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic represents an external shock that has prompted a variety of organizational responses. Recognizing the pivotal role that alliances fulfill in how firms deal with external shocks, we present an alliance-shock framework. Our framework stipulates that a firm’s response to an external shock is driven by (1) the extent to which the alliance portfolio functions as a buffering mechanism (that is, narrow versus broad) and (2) how decision-makers categorize the external shock (that is, opportunity versus threat). Based on these two dimensions, we infer four prototypical alliance-shock responses: (1) shock-shaping, (2) shock-adaptation, (3) shock-stabilization, and (4) shock-absorption.

Keywords: COVID-19; Alliance; Pandemic; Flexibility; Framework; Firm’s local environment; Business; Opportunity-Threat

Research Article

A recent report by IBM [1] highlighted that, in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, “Outperformers – in clear contrast to Underperformers – report a heightened emphasis on partnerships. Asked to identify those factors that increased in importance most in 2020, 63% of Outperformers identify partnerships, compared with only 32% of Underperformers.” Without question, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic represents an external shock, which is defined as an unexpected radical change that dramatically affects business operations. Whereas differences in national policies (such as trade and mobility regulations), industry dynamics (such as an increased need for technology-driven solutions), and organizational capabilities (crisis management capability, for example) explain variation in companies’ responses, here we suggest that a firm’s alliance portfolio – that is, the bundle of alliance agreements a firm established to attain its goals [2] – fulfills a critical role in how firms respond to external shocks. To advance understanding about the role alliance portfolios play in absorbing external shocks, we develop an alliance-shock framework comprised of four generic alliance-shock responses. The framework stipulates that a firm’s response to an external shock results from the interplay between (1) the extent to which a firm’s alliance portfolio functions as a buffering mechanism and (2) decision-makers’ categorization of an external shock as an opportunity of threat to their business.

Alliance Portfolio: Buffer against External Shocks

In order to gain additional opportunities and enhance their competitive advantage, firms are increasingly building and maintaining multiple alliance relationships simultaneously that, together, constitute a firm’s alliance portfolio [3]. In an environment without external shocks, alliance portfolio configuration and coordination enables firms to create and capture synergies in support of exploration and/or exploitation objectives [2]. Extending this logic, we suggest that an alliance portfolio in addition functions as a protective mechanism against external shocks. Alliance portfolios protect a firm from external shocks through resource buffering [4]. External shocks may result in decreased resources in a firm’s local environment, increased uncertainty about the viability of the business model, and external shocks may increase threats to firm survival. Alliances such as R&D partnerships, supplier arrangements, and go-to-market collaborations enable a firm to access supplemental resources, mobilize resources, or protect key resources, or allow for resource utilization in new ways. Investigating the survival of new biopharmaceutical ventures during the 2008 financial crisis, Xia and Dimov [5], for example, reported that exploration alliances, which have a long‐term orientation, make a firm more vulnerable to external shocks. In contrast, exploitation alliances, as well as a balance between exploration and exploitation alliances – which underlie short‐term performance – enable the firm to sustain external shocks.

To capture how different alliance strategies relate to resource building and utilization, we draw on Hoffmann [6], who distinguished among three generic types of alliance strategies. Firms forge core exploration alliances with the intent of developing new resources and capabilities and exploring new market opportunities. Goals are typically long-term and goal attainment occurs under conditions of uncertainty. Via core exploration, a firm seeks to expand and deepen its resource endowment. Through probing exploration alliances, firms seek to reactively adapt to unfolding environmental dynamics. The aim is to broaden the resource base and create strategic flexibility by exploring new opportunities without making high and irreversible investments. This involves using different alliances and making selective follow-up investments depending on the development of important environmental characteristics. Stabilizing exploitation alliances are forged to commercialize resources and capabilities gained through exploration. They stabilize the environment – for example, through long-term procurement contracts and alliances with rival firms (that is, coopetition) – and help refine and leverage the built-up resources to achieve a sustained and efficient exploitation of established competitive advantages. Conditional on the configuration of the alliance portfolio, a firm may possess narrow or broad buffering capacity to deal with external shocks. An alliance portfolio buffering capacity is considered narrow when a firm predominantly has forged alliance partnerships in pursuit of one alliance strategy. A firm with mainly stabilizing-exploitation alliances (for example, procurement and supplier alliances) will seek to reinforce these arrangements to deal with external shocks. Core-exploration alliances enable firms to penetrate new emerging markets (such as go-to-market alliances), whereas probing exploration alliances enable a firm to quickly and flexibly respond to emerging opportunities (for example, R&D alliances). In contrast to a narrow portfolio, a broad alliance portfolio provides a firm with strategic flexibility. Its buffering capacity originates in a balanced portfolio comprised of core exploration, probe exploration, and stabilizing exploitation alliances. A broad alliance portfolio allows firms to alternate between and/or simultaneously pursue different alliance strategies, offering them multiple avenues to deal with the ramifications of an external shock.

External Shocks: Opportunity or Threat

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatic consequences, although the depth of ramifications differs across industries. The airline industry, hospitality services, cultural and entertainment sector, and physical retail are examples of industries that have been disproportionally and adversely affected. By contrast, COVID-19 has also accelerated growth in industries, such as online retail, technology, and healthcare. Therefore, paradoxically, despite the dramatic social and economic consequences, the COVID-19 pandemic simultaneously represents a threat and an opportunity. We draw on the work by Dutton and Jackson (1988) and suggest that decision-makers’ categorization of an external shock – opportunity versus threat – informs and guides their organizational response to an external shock. Categorizing a shock as an ‘opportunity’ means that decision-makers perceive a positive situation with (ample) opportunities. Future gains are likely, and decision-makers have a fair amount of control with regard to formulating and implementing organizational responses, which tend to be externally oriented (such as new markets and new products). For example, in response to the COVID-19 crisis, GE Healthcare entered into a collaborative agreement with Ford Motor Company to produce medical ventilators [7].

By contrast, a ‘threat’ categorization means that decisionmakers perceive a negative situation encompassing hazards and challenges. Future losses are likely, and decision-makers have little control in terms of effectively dealing with repercussions; consequently, organizational responses tend to be internally oriented (such as, cost savings and restructuring). For example, many airlines announced drastic cost-reduction plans to face the uncertainties of the lack of travel due to COVID-19 [8] and Akzo- Nobel put a strong focus on margin and cost savings in response to COVID-19 headwinds [9].

An Alliance-Shock Framework

Building on the alliance portfolio as buffer and opportunitythreat logics, we propose an alliance-shock framework. Our framework stipulates that a firm’s response to an external shock is driven by (1) the extent to which the alliance portfolio functions as a buffering mechanism (that is, narrow versus broad) and (2) how decision-makers categorize the external shock (that is, opportunity versus threat). Based on these two dimensions, we infer four prototypical alliance-shock responses: (1) shockshaping, (2) shock-adaptation, (3) shock-stabilization, and (4) shock-absorption (Figure 1). Our alliance-shock framework is grounded through an in-depth conversation (focus group) with alliance executives. During an interactive guided group session with 15 participants, the notions of alliance buffering and opportunity-threat categorization were discussed and illustrated with real-life examples. Also, insights received through a questionnaire among 47 alliance managers were used to further corroborate the alliance-shock framework.

Shock-shaping Response

To deal with the repercussions of an external shock, firms with a narrow alliance portfolio and categorizing an external shock as an opportunity are likely to opt for a shock-shaping response. Because a firm’s portfolio buffering capacity is confined to its dominant alliance strategy (core exploration, probe exploration,or stabilizing exploitation), a firm will seek to identify and capture business and resource domain strengthening opportunities, while leveraging the strength of existing partnerships. By reinforcing existing relations, a firm seeks to incrementally identify and capture opportunities, enabling it to expand and deepen the firm’s resource endowment in a focused manner. Shock-shaping responses during COVID-19, for example, relate to collaborative endeavors where firms reinforce their existing alliance strategy to strengthen their competitive advantage. Recognizing the value of its partner network, in response to COVID-19, SAP offered partner program level protection, flexibility in using market development funds, and subsidies for training and certifications to its channel partners [10]. Or, as an alliance manager involved in core-exploration alliances put it: “by swiftly adapting to the new situation they have been able to strengthening three alliances by expanding the co-creation and joint go-to-market.”

Shock-adaptation Response

Akin to shock-shaping, a shock-adaptation response entails the exploration to acquire new resources and capabilities, prompted by viewing the external shock as an opportunity. Firms with a broad alliance portfolio leverage existing alliance relations and forge new partnerships to capitalize on strategic flexibility while seizing an opportunity to learn and change. In doing so, firms use alliances to broaden their business and resource domains in response to an external shock. Consequently, firms are likely to accelerate growth under adverse conditions, while embracing risk and uncertainty. Shock-adaptation alliances during COVID-19, for example, are coopetition alliances whereby competitors team up to seize an opportunity and also to fight the pandemic. Examples include the Sanofi–GSK and Pfizer–BioNTech alliances to jointly develop, produce, and distribute COVID-19 vaccines. On the other hand, we have seen alliances established by companies to seize new opportunities outside of their traditional realm. An example is Panton, a healthcare design agency, teaming up with bed- and mattress manufacturer Royal Auping to produce high-quality masks for care professionals.

Shock-stabilization Response

When an external shock constitutes a threat to a firm’s survival, the focus shifts towards efficiently exploiting existing resource endowments and protecting a firm’s competitive advantage. Firms with a narrow alliance portfolio, under threat conditions, are likely to opt for a shock-stabilization response to absorb the repercussions of an external shock. Their focus shifts to business and resource domain restructuring; developing and implementing incremental changes initiatives within and through existing alliances relationships to attain, for example, cost savings and avoid further revenue losses. Consequently, alliance agreements are adapted to new circumstances, promising projects are delayed or ended, and alliances are prematurely terminated. Shock-stabilization responses during COVID-19, for example, relate to initiatives where firms reconsider the arrangements with existing suppliers. Heavily impacted by the pandemic, Delta and KLM strengthened their existing alliance agreement by offering quarantine-free flights to the Netherlands. Light manufacturer Signify reported good results over the first financial year that the pandemic struck. Nevertheless, Signify has concerns about availability of materials and supplies from its supply chain partners. As a result, Signify announced further restructuring of the organization, including lay-offs and cost cutting, to adapt to potential pandemic aftershocks. In response to supply and demand volatility caused by COVID-19, Walmart began to invest in suppliers relations, further integrating online and offline operations, and fine-tuning its omnichannel offerings, bringing the cost per unit down [11].

Shock-absorption Response

Akin to shock-stabilization, a shock-absorption response shifts a firm’s focus towards efficiency and protective considerations. However, firms with a broad alliance portfolio can leverage strategic flexibility and are likely to deal with a shock through business and resource domain extension. Accepting risk and uncertainty levels, these firms search for new alliance partners to protect competitive advantages, increase internal efficiency, and explore how existing under-utilized resource and capabilities can be used with external partners. Utilizing the broadness of their alliance portfolio, firms use a mixture of alliance arrangements to internally absorb the external shock . Shock-absorption responses during COVID-19, for example, relate to initiatives where firms forge alliance arrangements to utilize existing resource endowments in new ways. VDL, an industrial equipment conglomerate, is potentially impacted by the shock as BMW announced it will end the production partnership by 2023. The new partnership with DSM to jointly produce medical face masks represents a domain-extending response that arises from insufficient supply of medical face masks. In the words of an alliance manager: “Organizations we were familiar with now recognize their own weak spots and are more willing to explore ‘survival’ strategies with complementary organizations.”

Admittedly, the four alliance-shock responses are analytically distinct. In practice, established firms may operate a multibusiness enterprise, meaning that multiple alliance portfolios and opportunity-threat categorizations across business units exist. Consequently, these firms may resort to multiple alliance-shock responses simultaneously. In addition, our framework assumes a one-side perspective: the response of one firm. Alliances encompass two (or more) partners, each one opting for a specific response. As an initial response to supply shortage due to the COVID pandemic, Philips and KLM established a special cargo air bridge between The Netherlands and China. This air bridge can be seen as a shock- stabilization response by KLM, while for Philips it was a shock-absorption response.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a shift in how firms view and manage their alliance relationships in pursuit of survival and growth. Whereas alliances are widely considered to have become increasingly important to cope with COVID-19 ramifications, it also appears that, in practice, fewer alliances are being established [1]. Firms that are smarter in their alliance endeavors, however, are more able to deal with external shocks. This paradox – need versus ability – supports our contention that pro-actively managing an alliance portfolio, in addition to dyadic alliance management, becomes increasingly important for firms. Whereas effective alliance portfolio configuration and coordination enable firms to attain strategic objectives under normal conditions, wellmanaged alliance portfolios also function as an (additional) buffer against external shocks, irrespective of whether a firm operates in a benevolent or adverse environment.

References

- IBM (2021) Find your essential How to thrive in a post-pandemic reality. IBM Business Institute for Value.

- Tjemkes BV, Vos P, Burgers K (2017) Strategic Alliance Management. Routledge, Abingdon.

- Wassmer U (2010) Alliance portfolios: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management 36(1): 141–171.

- Miner A, Amburgey T, Stearns TM (1990) Interorganizational linkages and population dynamics: Buffering and transformational Shields. Administrative Science Quarterly 35(4): 689-713.

- Xia T, Dimov D (2019) Alliances and Survival of New Biopharmaceutical Ventures in the Wake of the Global Financial Crisis. Journal of Small Business Management 57(2): 362–385.

- Hoffmann WH (2007) Strategies for managing a portfolio of alliances. Strategic Management Journal 28(8): 827- 856.

- Ford (2020) Ford to produce 50,000 ventilators in Michigan in next 100 days; partnering with GE healthcare will help coronavirus patients.

- Harry R (2020) Emirates announces cost-reduction plan in response to Covid-19.

- Akzo-Nobel (2020) AkzoNobel’s Q2 results show strong focus on margin and cost savings in response to COVID-19 headwinds.

- Whiting R (2020) SAP Aims to Turbocharge Aid to Partners in ‘Unprecedented’ COVID-19 Crisis.

- Cosgrove E (2020) Walmart execs say stockouts track with COVID-19 hot spots.