Safety in Schools and Their Surroundings: A Case Study in Istanbul

Halil Ibrahim Bahar*

Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Aksaray University, Turkey

Submission: November 16, 2020;Published: December 01, 2020

*Corresponding author: Halil Ibrahim Bahar, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Aksaray University, Turkey

How to cite this article:Halil I B. Safety in Schools and Their Surroundings: A Case Study in Istanbul. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2020; 6(1): 555680.. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.06.555680

Abstract

This work proposes school safety be considered in terms of the wider perspective of urban safety in general, taking a totalitarian approach and presenting the basic problems and possible solutions inherent within the issue of safeguarding schools. School safety should not merely lie within the boundaries of any one school. School safety must be considered as one aspect of urban safety as a whole. Data presented in this article was collected by the International Strategic Research Organization (ISRO) as part of the four year, 2008–2012, Istanbul Urban Safety Project. The article does not consider threats to safety inside the school and its environs as matters to be dealt with by the police, but rather takes a holistic approach in the context of wider social problems to which the solutions lie in the implementation of comprehensive policies that include the school, the family, the social environment and policing in that order.

Keywords:School violence; Substance abuse; Bullying; Safe schools; Istanbul

Research Article

A safe school can be defined as an environment in which students, teachers, school managers, administrators and anyone else employed in the school, experience no violence nor fear of violence [1]. Alongside this, other important factors in the concept of a ‘safe school’ would seem to be the physical condition of the school and safety within the area surrounding the school. Safe schools are not just places where no crimes are committed and thus there is no possibility of being the victim of crime; many other elements must also be taken into account including the attitudes and behaviour of teachers, managers and anyone employed in the school, the design of the school, the condition of buildings and the nature of internal computer networks. Incidents of physical, verbal or psychological abuse between students do not just take place in the classroom or on the school grounds. Such incidents may all too often occur outside the physical boundaries of the school. Hence, the only realistic approach is to consider school safety inside and outside the actual school boundaries, defining the problems and possible solutions in the context of this wider area. Heading the list of possible threats to students in the school and its environs must be the issue of substance abuse. This threat increases when some substances are easily available and cheap to acquire. The most important matters in the context of safety within the school and its environs would seem to be the issues of bad friends, students who hate school, substance dependency and school organization. Furthermore, it has to be accepted that substance abuse is the most important factor and presents the greatest threat to school safety. In terms of all types of exploitation and bullying, of which children may become victims, the most important role belongs to the educators. They should observe the beginnings of any type of exploitation and be able to reduce the effects of psychological problems becoming entrenched in their students. There may be cases in which explicit victimization has not been established, but children are not succeeding or attract a multitude of disciplinary punishments. Educators should be able to identify changes in their students and take preventative measures against emotional exploitation. It is also important that the school be in a convenient location to ensure the health, education and social development of its students. There are studies which show that the actual number of students in a school can have an impact on school safety and engagement with crime. One such study carried out by Ankara University Institute of Educational Sciences concluded that schools with less than 600 students had a lesser incidence of crime [2].

Safety in the area surrounding a school, and safety within the school itself, should be treated as separate entities. Levels of crime, violence and weaknesses in the social order in the area surrounding a school, and the problems which give rise to these levels, are indicators of safety in that area. Work to establish safety in a school and its environs begins with discussion of such issues, which will produce a range of causal elements headed by identification of responsible actors who have witnessed violence, are aware of its roots and embrace the need for its eradication [3- 6]. Crime may play an important role in students’ lack of success in school. The issue of school safety is one on which the Ministry of Education, local leaders, universities, security and social services have focused and in recent years significant achievements have been recorded. Indeed, professional support is available from the Ministry of Education and the police. This article addresses safety in schools and their environs; identifies threats to such safety and bodies with responsibility for preventing those threats; examines other work in this context; attempts to reveal weaknesses and proposes solutions, all linked to the broader field of urban safety.

Violence in school and its surroundings

Violence can take many forms including physical, verbalemotional- psychological, sexual and economic violence. Physical violence includes any kind of contact intended to hurt: slapping, pushing, arm twisting; as well as the use of any form of weapon to cause injury. The umbrella term verbal-emotional-psychological violence includes such behaviour as denigration; mockery; denying an individual’s right to make decisions; confrontation; barriers to personal development such as forbidding an individual to confide in family or friends; belittling an individual in economic or socio-cultural terms. In other words, within a school, any form of patronizing or demeaning language, whether used by students when speaking to each other or by teachers, falls within the scope of verbal violence. Sexual violence includes such acts as harassment, indecent molestation, incest and forced marriage. It is noticeable that research in schools would seem to invariably encounter such acts. The final form of violence, economic violence, covers being forced to work; being detained as a consequence of such work; making use of others’ property without their permission and so on [7]. All these forms of violence defined within the literature may not necessarily be viewed as ‘violence’ by the community at large; hence they can be viewed as acceptable within schools. This should be taken into account by the Ministry of Education when designing projects aimed at the prevention of violence in schools. In the words of Güz: “Violence be it physical, psychological, verbal, sexual or political can be found in many fields: in general within society and particularly between individuals (Güz, 2006, p.81). Many studies of schools in Istanbul have revealed that high numbers of students are made to work on the street. These studies clearly show that such economic violence belongs in the field of safety within a school and its environs [8,9].

Examples from other countries show an increase in violent incidents in schools [10,11]. Such an increase in the occurrence of violence in the USA led to the passing of the 2008 School Safety Enhancement Act, which listed measures necessary to increase safety in schools in the following order: 1) Separate budgets for school safety to be increased; 2) Poorer communities to be made aware of how they can access these budgets; 3) Approved areas in which the budget may be spent to be broadened; 4) Principles to be applied in this matter to be developed and the formation of a special unit comprised of parties from interested organizations to be announced; 5) Emergency intervention to be improved and implemented to include annual evaluation carried out by higher education associations. For any program targeting violence to succeed, all its components and initiatives must be well coordinated and form part of a whole school approach [2].

There have been interesting results obtained in the context of measures and practices within programs created to establish safe schools. School managers should be aware of the importance of the school being well-lit, functional and aesthetic and, in terms of the school’s socio-cultural climate, that it is built in the right location. With regard to the physical condition of schools, clear differences can be seen between private and public establishments. Private schools would seem to have embraced the safe school concept to a higher degree. Differences can also be seen between primary and secondary schools, with the latter placing greater emphasis on aspects such as lighting, functionality and aesthetics. Similarly, differences can also be seen between general sixth form colleges and their counterparts devoted to science, technology and other vocational training. The science-technology-vocational colleges would seem to have taken greater steps in terms of developing school safety and maintaining the physical condition of premises [13].

It is crucial that communication and working partnerships are fostered between civil society organizations, security forces, education and municipal authorities, together with central government agencies who have an interest in urban security. Needless consumption of time and energy can be avoided if efforts to eradicate violence in schools, using action plans or other types of specific project, are made in a coordinated fashion based on sound data. Work on ensuring safety in schools and their environs would seem to comprise conceptualization of safety leading to projections for particular schools. Indeed, projects devised by security organizations and education authorities in response to specific requests have proved highly effective in terms of progress towards a solution to the problem. However, to truly settle this issue it would seem advisable to involve a greater range of expertise, developing effective and mutually beneficial relationships around safety between managers-students-teachers.

Substance dependency within violence in schools and their surroundings

The age at which young people begin to engage in substance abuse is becoming younger all the time, presenting a clear need for appropriate strategies to be implemented to prevent substance abuse amongst high risk groups of children and adolescents. In this context parents and schools are vitally important [13]. Substance dependency is among the most important problems facing young people today. Research shows that the group at greatest risk of engaging in substance abuse and becoming dependent are young people between the ages of 12-24 years, the vast majority of whom are engaged in formal education [14]. At the same time substance dependency can be seen as one of the basic threats to safety within schools and their surroundings. Nowadays young people can easily obtain drugs, and widespread drug dependency is often cited by educators as one of their major concerns. A range of bodies, apart from the professionals at the Ministry of Education, go into schools to do work in this context but their presence can have a negative effect. To avoid this problem, drugs education must be delivered by experts who focus on the need to avoid using drugs, rather than presenting the subject in a fashion that may encourage experimentation. All too often it would seem that bad presentations in schools merely serve to focus the attention of young people on drugs.

The police are not the only ones who should be taking steps to fight the war on drugs; it has been shown that raising awareness of this issue in the wider community can have a positive, supportive effect [15]. Consideration must also be given to parents and teachers who resort to corporal punishment to instil discipline, which may increase the likelihood of children becoming substance dependent, and certainly plays into the hands of those selling drugs as a commercial enterprise [16].

Methodology

Data presented in this article was collected by the International Strategic Research Organization (ISRO) as part of the four year, 2008–2012, Istanbul Urban Safety Project. Quantitative and qualitative methods were used in the study. Quantitative methods included a questionnaire survey and analysis of secondary data. With regard to the qualitative dimension of the research, semistructured, open-ended interviews took place with a number of senior officials involved in urban safety in Istanbul. Almost 100 such interviews were carried out with Istanbul MPs, neighborhood leaders, representatives of the Governor’s office, senior personnel in Istanbul city-wide and district education authorities, officials from the police and judiciary, academics from Istanbul-based universities, leaders of primary and secondary schools, private citizens and representatives of the chambers of commerce and manufacture. This stage was seen as the establishment of relationships between a wide range of stakeholders in urban safety in Istanbul, together with the facilitation of dialogue and coordination between public and private organizations.

Sampling

In terms of the questionnaire survey, the sample was prepared using baseline data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK) and it was planned to apply multi-level, stratified group techniques. However, it transpired that this would necessitate extremely large samples, the administration and management of which would have been beyond the scope of the project, hence the decision was taken to utilize probability sampling. Random sampling was deemed inappropriate for a city the size of Istanbul in which each district and neighbourhood may contain a wide range of social and physical conditions. In the event, baseline data led to a representative sample of 3140 households.

Much time was devoted to questionnaire design prior to a pilot exercise. Each question was subjected to repeated, detailed examination in the context of dependent, independent and control variables. The questionnaire was piloted in the following European districts of Istanbul: Bakırköy, Sarıyer, Beşiktaş; and on the Asian side of the city in Üsküdar, Ümraniye and Kadıköy. The piloting involved 200 questionnaires administered to 100 households. Following the pilot exercise, 3140 questionnaires were distributed to households of which 2309 (73.5%) were returned with all questions answered, save for some gaps in the optional personal details.

The 2309 household participants can be broken down into 1315 females and 994 males aged between 18 and 65 (X = 38.35; SS = 10.7). Of these participants some 1659 (72.8%) identified as married and 484 (21.2%) were single; levels of education in this sample ranged from primary school or lower 450 (19.7%); middle school completed 580 (25.4%); finished high school 891 (39.1%); and 358 ( 15.7%) were university graduates. Some 1187 (52%) of the participants claimed to be unemployed.

Data collection instrument

The questionnaire made use of demographic variables alongside questions directly related to the subject under consideration. These questions were designed by research staff within the Istanbul Urban Safety Project following a broad search of the available literature. participants were requested to provide their gender, age, level of education, occupation and marital status. Specific questions related to school safety were: “Do you think those in charge at your local school have taken sufficient preventative measures to ensure safety in the school?”(Q3); “Have the police taken necessary measures to ensure safety around the school?” (Q4); “What are the most serious threats to students in school?” (Q5); “Who should be the first responder to any incident within the school?” (Q6). Data collected underwent Pearson correlation analysis, independent group t-test, and ANOVA within the SPSS data analysis software.

Research implementation

Respondents were given an overview of the general aims of the study and necessary instructions for completion of the questionnaire were provided. All members of the sample were told that their participation was entirely voluntary and they should leave blank any questions to which they did not wish to respond. Finally, it was made clear that data gathered from the study would be confidential and would be utilized for scientific purposes.

Research findings and discussion

School security

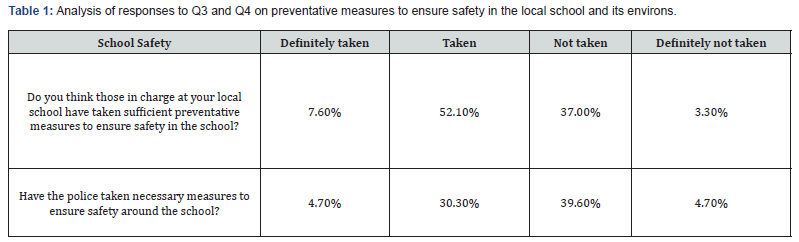

Questions on neighbourhood school security were designed to give insights into individual anxieties about generic safety in the area in which they lived. The questions sought respondents’ views on preventative safety measures in schools and their environs, perceived threats and dangers for school students and, in the event of an incident, where the initial responsibility for dealing with it lies. The quantitative date thus gathered was analysed using the SPSS computer program. This stage also included analysis of demographic data emanating from the sample which gave values for percentage frequency, mean and standard deviation. Tables below give frequency results for the questions relating to school safety (Table 1).

One of the questions designed to elicit views on school safety, within the broader scope of neighbourhood safety, asked: “Do you think those in charge at your local school have taken sufficient preventative measures to ensure safety in the school?” Responses were: “they have definitely taken” 7.6%; “they have taken” 52.1%; “they have not taken” 37%; “they have definitely not taken” 3.3%. A similar question asked for views on whether or not the police had taken all necessary measures to ensure safety in the area around a school and responses were: “they have definitely taken” 25.4%; “they have taken” 30.3%; “they have not taken” 39.6%; “they have definitely not taken” 4.7%. (Table 2) Participants in this research felt that the greatest threats to students in school, in order of severity, were: substance dependency 844 (33.9%); having a bad circle of friends 768 (30.8%); disorder in the school and its surroundings 480 (19.3%); students’ hatred of school 382 (15.3%); other threats 0.7%. As can be seen, participants felt the responsibility for first response to any incident within the school lay with: school’s private security 923 (37%); teachers 660 (26.5%); school principal 611 (24.6%); police 230 (9.2%); parentschool partnership 56 (2.3%); other 0.3% (Table 3).

It is clear that a high number of respondents felt that steps taken by school leaders to ensure safety within the school, and by the police in the area surrounding the school, are inadequate. It would seem important that so many participants worried about safety in school and its surroundings. In particular, attention should be paid to the high number that expressed their anxiety about the threat to students inherent in having a bad circle of friends, substance abuse and disorder within the school and its surroundings. In the final set of results presented above, a mere 9.2% chose the police as the first responders to any incident in the school, in other words they believe the police do not have a role to play in events inside the school. This leads to the need for a multi-agency approach to safety in school and its environs, one which involves education authorities, local leaders, the city governor’s office, the police and other stakeholder individuals and organizations. The views on school safety of participants in the study were further investigated in terms of two variables: necessary security measures taken by school leaders to ensure safety in a school and taken by the police in terms of the school surroundings; and correlation analysis was carried out to examine any relationship between the two. This revealed that those who thought necessary measures had been taken by leadership within the school, also believed that the police had taken all necessary steps to ensure safety in the area surrounding the school (r= .55, p<.000).

In order to examine the effect of gender perceptions of the measures taken within the school by school leadership, and those taken in the surrounding area by the police, was also investigated by means of a t-test. With regard to measures taken within the school, no difference in perception by gender was found (t (2231) =1.82, p>.05). However, in terms of measures taken by the police in the school surrounding area, a statistical difference in accordance to gender was revealed (t (2237) = 5.58, p<.01). It can be stated that females (X=2.65, SS= .66) perceive the police had taken fewer measures than did males (X= 2.49, SS= .71).

Participants’ views were also seen to be different according to their level of education (F (3.2201)=11.59, p<.01). Those with only primary school or lower levels of education (X= 2.52, SS= .67) perceived more strongly that school leaders had not taken necessary measures within the school, than did their counterparts with middle school (X= 2.41, SS= .67), high school (X= 2.35, SS= .62) or university level (X= 2.26, SS= .75) education. It would seem that as the level of education increases, so do the participants’ views that necessary security measures have been taken within schools.

Differentiation according to level of education was also observed in participants’ views on measures taken by the police to ensure safety in the area surrounding their local school (F(3,2207)=20.79, p<.01). Those with only primary school or lower levels of education (X= 2.79, SS= .69) perceived more strongly that police had not taken necessary measures within the school, than did their counterparts with middle school (X= 2.58, SS= .67), high school (X= 2.53, SS= .66) or university level (X= 2.44, SS= .75) education. The difference between those who had completed middle school (X= 2.58, SS= .67) and those who had gone to university (X= 2.44, SS= .75) is very clear. It could be said that as the level of education rises, participants think more about such matters as police effectiveness in the schools surrounding area. With regard to who should be first responder in the event of any incident within the school, participants opted for: school’s private security 857 (37%); teachers 612 (26.5%); school principal 568 (24.6%); police 212 (9.2%); parent-school partnership 53 (2.3%).

Actors responsible for safety in school and its surroundings

Results from the quantitative and qualitative findings, define those responsible for establishing safety in a school and its environs as private security personnel employed by the school, teachers, school principals, the police and parent-school partnerships in that order. Furthermore, results also showed that in order to establish safety in schools the police must work in partnership with other actors. To establish partnership working between educators, police and parents, complete with the necessary awareness raising activities, is a very demanding, complex exercise. On the one hand parents must be fully involved and informed; on the other, teachers and police must receive appropriate training with people-centred methods employed throughout. In 2006 the Ministry of Internal Affairs published a circular on the establishment of school safety, which ordered school principals together with city or provincial governors, depending on the school’s location, to form Violence Prevention Working Groups [17]. Over the past two years, this circular has led to the implementation in schools of ‘Violence Prevention and Reduction Strategy Action Plans’ in which the police are also involved. The framework of these Action Plans includes formation of parent-school partnerships, whilst within the school first responders are designated as teachers and administrators. Indeed, not only are the educators given this response role, they are also responsible for training in the context of violence and for the promulgation of appropriate response strategies. The police are not only denied any first response role, they are not to enter schools whatever security issues may arise, in fact from the point of view of educators, any form of police presence would seem to be undesirable.

When seeking solutions to security problems in general, it would seem the police are usually perceived as providers of such solutions, not teachers and school managers. Work done on safety in school and its environs highlights the need for teachers, school administrators and experts to all play a large role. Within the research for this project, many other studies were evaluated and without exception all pointed to the importance of the behaviour of teachers and administrators in school as a crucial element in the establishment of a safe school. One of the main causes of violence in schools is prejudice and intolerance amongst the students. Teachers must be trained to identify and control such behaviour amongst the students before it leads to entrenched resentment [18]. Research by various experts has shown that there is a high correlation between violence amongst students in schools and teachers who display negative attitudes. In 2007 Mertoğlu and Doğutaş, based at Kent State University in the USA, conducted a survey comprising face-to-face interviews with 884 students in 11 schools which examined the relationship between violence in a school and a range of factors including the school’s academic program, its physical condition, teacher attitudes and whether or not students felt they belonged in the school; results determined that the strongest relationship was between violence and teacher attitudes [19]. A similar research study had already been carried out by the governor of Istanbul working with the Ministry of Education and two Istanbul children’s charities. Results from this study were in parallel with those of the later work done in the USA. From 1997-2005 some 799 students from 13 schools in Istanbul took part in the study, which concluded there was a positive correlation between teachers’ negative attitudes and the incidence of violence in a school [19]. This study also included training for teachers in how to manage without corporal punishment, effective classroom management, child development and other techniques to improve their performance and establish safe schools with higher academic achievement and lower rates of student drop out. Results showed that this approach had the greatest success in the poorest schools where bad physical conditions were accompanied by low standards of education. This work also highlighted the vital relationship between teacher awareness and the eradication of violence [19]. Mertoğlu and Doğutaş’ work also revealed the relationship between academic success and violence. Results from their work show that as violence increases, academic success falls [19]. Comparison of results from the USA with those from Turkey shows that the incidence of violence in Turkish schools is much lower than in their American equivalents. Furthermore, work which succeeded in improving schools where low socio-economic conditions prevailed in Turkey proved not to be replicable in the USA.

Efforts to solve the issue of the relationship between school teachers’/managers’ negative attitudes and the incidence of violence focused on improving the physical condition of a school, and making changes to academic and extra-curricular activities in that order. Training for teachers and managers was based on enabling them to achieve effective management in and out of the classroom, with the work being evaluated using a control group alongside those who had actually taken part in the training. Evaluation considered such factors as the environment, effectiveness of teachers’ performance, psychological and socioeconomic issues and the effect of teachers’ attitudes on their students. The work showed the importance of the teachers’ working environment with regard to the development and quality of educational opportunities. Another important result was that an unhealthy, threatening environment can have negative psychological and social impacts on both teachers and students [20-22].

Threats to school and urban safety are not confined to the school and its immediate environment. Problems such as drugs and prostitution originate outside the school environment and must be addressed by the police, not the educators. This is yet further grounds for all aspects of the issue of school safety to be considered comprehensively, and effective strategies put in place, by a multi-agency approach involving the school, parents, local leaders, police and health authorities.

Working partnerships between organizations and individuals

Young people have a choice of different routes through education and it is important that safety is considered in all of these choices to increase the effectiveness of all types of educational setting. It is vital that attention is paid to vocational education to ensure students’ interest and lead to their success. To ensure the success of any projects designed to increase school safety, managers and educators involved in such projects must be totally committed. Private schools may fear loss of students and thus try to avoid such initiatives. Projects which do take place should build on existing work in schools and educators can benefit from seeing work being carried out in other countries. Early warning systems can make a difference as uncovering suspicious behaviour in its infancy can contribute to school safety. Furthermore, there must be clear reporting systems in place to handle any incidents posing a threat to school safety. Work done by the Ministry of Education in this context needs to be made more widely available, with specific training for educators. A clear, safe reporting process must be put in place with training in its usage given to teachers and parents. Any program aimed at fighting violence in a school and its surroundings can only succeed if all its elements and initiatives are coordinated into a whole school approach [12]. In this context it is important to consider examples of preventative measures that have been implemented in other countries and led to, at the very minimum, a reduction in the number of victims. Students who have themselves been the victims of violence or bullying can play an important role in awareness-raising with both teachers and parents. Research has shown that a safe school is one in which the students are aware that they are receiving a high quality education. A safe school gives students equality of educational opportunity, makes them more aware, accustoms them to disciplined working and establishes the habit of lifelong learning [23-24].

Conclusion

To establish safety in schools and their environs, great benefit can be obtained from ‘school development plans’. Education authorities that have introduced such plans must bear in mind that they may be more effective if positive developments in terms of crime and misdemeanours in school are recorded. A school development plan has been defined as “a means to inform the public of a school’s educational philosophy, its aims and how those aims will be achieved [25]. The plan must include such elements as: details of all those working in the school, its buildings and equipment, timetable, funding, activities; student-centred information such as student evaluations, individual needs, meeting development targets; teachers’ preparation, homework setting, discipline management; fostering of school-parent relations; evidence of equality of opportunity for all students; health and safety; social and cultural matters [25-27].

The actual physical environment is important for safety in a school and its surroundings. Physical factors such as the quality of the school buildings, how they appear from the outside, internal design, standards of cleanliness, hygiene and maintenance can all have an impact on how safe students feel in a school environment. It must be borne in mind that improvements in any/all of these areas can have a preventative effect in terms of violence. There has been much debate on the issue of installing camera systems as a contribution to school safety with those opposed citing the intrusion on students’ privacy. It should be borne in mind that such systems may increase student confidence if used to control events in the school grounds rather than inside the buildings. Harmancı’s work demonstrated that, when examining the relationship between social environment and school, areas with a low crime rate have taken more crime prevention measures. In terms of entry and exit security in schools, together with closed circuit security camera systems, again there are marked differences between private and public establishments. Private schools use such systems more effectively. Furthermore, as with the physical conditions outlined above, security systems and safety in general would seem to be better in secondary than in primary schools and in science-technology-vocational colleges than in their equivalents offering general subjects [2]. A large responsibility for safety in school and its environs falls on the guidance services, all too often delivered by teachers. Teachers have the most important role to play in listening to children’s cries for help when they are being exploited or bullied. Even when there has been no request for help, victimized children may be identified by their under-performance in the classroom or from their lack of discipline. Teachers who take note of such changes in their students may be able to take appropriate preventative actions. Guidance work should involve experts in the field of psychology, and with the support of management, it is crucial that a ‘whole school’ approach is adopted. This will also include parties such as administrators and the school-parent partnership that would seem to be best utilized in terms of identifying problems peculiar to any given school and then working to clarify appropriate solutions.

Another important aspect of this issue is encouraging school leaders and their representatives to identify the problems they see in terms of safety in their school and its environs, together with identification of who or what may be causing the problem. This can only lead to students feeling safer in school. A strong, wellestablished working partnership between students-teachersparents- police should result in students having the confidence and trust in their educators, and all other school personnel, to be able to speak directly to them about any perceived safety threats. In terms of the role of the police, it would seem clear that training delivered by suitable experts could lead to improvements in relations between the police and schools. Such training would include identification of police personnel to work in schools, how best to deal with those employed within the school and especially how to approach highly sensitive young people, and such training would result in a situation in which school safety is ensured.

If the first responders to any incident which may be a threat to school safety are not the police, but the school managers and teachers, there is an implied negative attitude prevalent amongst the educators toward the police. The police’s approach to dealing with children and young people has long been debated with calls even made for the establishment of a specialized ‘Children’s Police’. It would seem that there will not be solutions to any of the problems raised in this article, until the police force as a whole can come to terms with the extended period of change in which it would currently seem to be mired. One of the most important groups within the community, that must take responsibility for issues affecting safety in school and its surroundings, is the family. When a student becomes a victim of violence or violent behaviour, the family has a vital role to play. At this point training is needed for a working partnership between educators and parents to ensure early warning for any suspicion of victimization. The family also plays a crucial role in terms of the personal development of children and young people. Experts have observed that young people developing within an organized family life setting are more likely to grow into young adults prepared to take responsibility for themselves and their actions. In particular, it is important that the family actually spend time together as a family. Children who do not receive enough interest and love from their family may rapidly turn to a bad circle of friends and find themselves involved in crime.

There is a need for an audit mechanism to record crimes and misdemeanours in schools across all sectors. This could lead to the development of new initiatives to counter such activity. With regard to work on countering substance dependency/abuse in schools, experts in the field must share their findings and, in general, more data is needed. As with other crimes, weaknesses in recording can only delay the emergence of solutions to the problem. Finally, the subject of reducing violence is constantly debated in the media, to the point at which it would seem to be fuelling the fire. Perhaps the media could turn its attention away from endless speculation around preventative measures, instead focusing on how educators, parents and young people live with violence. Yet another area in which there would seem to be a need for the necessary awareness raising.

References

- Phillips R, Linney J, Pack C (2008) Safe School Ambassadors, San Francisco Jossey-Bass,California, United States.

- Harmancı MF (2009) Problems in Ensuring Safety in Schools and Solutions According to the Opinions of Education and Security Organization Managers: Diyarbakır Provincial Example, Unpublished PhD thesis, Ankara: Ankara University, Institute for Educational Sciences.

- Dönz B, Güven M (2003) Task Perceptions of Managers and Teachers in General High Schools regarding School Safety. Contemporary Education 28(304): 17-26.

- Işık H (2004) Physical Order of Learning Environments. In: Fat M and Turan S (eds.), Classroom Management, Teaching, Ankara: Pegem Publications, pp. 11-24.

- Ögel K, Tari I, Yilmazçetin CE (2005) Prevention of Crime and Violence in Schools, Istanbul: Re-Publications.

- Celik K (2007) Emergency Management in Schools, Ankara: Memoir Publishing.

- World Health Organization (2002) World Report on Violence and Health.

- Bulut S (2008) Examination of student-to-student violence in schools by archival research method in terms of some variables. Journal of Abant Izzet Baysal University Faculty of Education 8(2): 23–38.

- Durma E, Gürgan U (2005) Trends in violence and aggression of high school students. Turkish Journal of Educational Sciences 3(3): 253-269.

- Crone DA, Carlson SE, Haack MK, Kennedy PC, Baker SK, et al. (2016) Data-Based Decision-Making Teams in Middle School: Observations and Implications from the Middle School Intervention Project. Assessment for Effective Intervention 41(2): 79-93.

- Solberg ME, Olweus D, Endresen IM (2007) Bullies and victims at school: Are they the same pupils? British Journal of Educational Psychology 77(2): 441-464.

- Smith PK, Debra J, Pepler DJ, Rigby K (2004) Bullying in Schools: How Successful can Interventions Be? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Çelik G, Attepe S (2011) Importance of School Social Work in Prevention of Drug Abuse. In: Doğutaş C (edn.), Protection of Children from Substance Abuse, Ankara: AsayişDairesiBaşkanlığıYayınları, pp. 245-257.

- MEB (1999) Department of Health Affairs, Circular on Substance Abuse.

- Doğutaş C, İlter A (2011) Model Practices in Protection of Children from substance Abuse and Crimes in the City of Ağrı. in: Doğutaş C (edn.), Protection of Children from Substance Abuse, Ankara: AsayişDairesiBaşkanlığıYayınları, pp.135-149.

- Çeltikçi E (2011) A Look at Our Understanding of Discipline in Families and Schools in terms of Its Effects on Substance Abuse Problem. In: Doğutaş C (edn.), Protection of Children from Substance Abuse, Ankara: Public Security Department Publications, pp. 285-298.

- MEB (2006a) Strategy Action Plan for The Prevention and Reduction of Violence in Educational Environments, Ankara: MEB.

- Furin TL (2008) Combating Hatred: Educators Leading the Way, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

- Mertoglu M, Doğutaş C, Cemalcı Z, Baydar N (2008) School Belonging, School Satisfaction and Measures to Be Taken, Istanbul: Cem Offset Printing.

- Mertoglu M (2011) Examining the Impact of Education given to Teachers and Administrators in Primary Schools in Intensively Migrating Areas in Istanbul, An Experimental Study. Journal of Forensic Medicine of Turkish Clinics 2, pp.72-84.

- Mertoglu M (2012) Rehabilitation and Education Centers for The Protection of Children Who Have Been Driven to Crime. Review of Turkey America Examples Fasccul Journal, pp.24-29.

- Mertoglu M, Aydın O (2012) Analysis of the Relationship Between the Lives of the Primary Secondary School Students Regarding Domestic Violence at Home and Their Academic Success Procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 55, pp.1233-1242.

- Finn P McDevitt J, Lassiter W, Shively M, Rich T (2005) Case Studies of 19 School Resource Officer (SRO) Programs, Report prepared for Brett Chapman National Institute of Justice.

- Granberg-Rademacker JS, Bumgarner J, Johnson A (2007) Do School Violence Policies Matter? An Empirical Analysis of Four Approaches to Reduce School Violence. Southwest Journal of Criminal Justice 4(1): 3-29.

- MEB (2006b) Ministry of National Education, General Directorate of Special Education Guidance and Advisory Services, Circular on the Prevention of Violence in Schools, 2006 CIRCULAR NO: 2006/26.

- Galand B, Lecocq C, PhilippotP (2007) School violence and teacher professional disengagement. British Journal of Educational Psychology77(2): 465-477.

- FallH (2006) Violence and Youth's Perception of Violence.In: Prevention of Violence against Children and Adolescents, Ankara: Ankara Police Department.