Opportunism and Opportunity Cost as Antecedents of Participatory Behavior

Junesoo Lee*1, Heung-Suk Choi2 and Seungjoo Han3

1Associate Professor, KDI School of Public Policy and Management, 263 Namsejong-ro, Sejong, Republic of Korea

2Professor, Korea University, 145 Anam-ro, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea

3Associate Professor, Myongji University, 34 Geobukgol-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Submission: November 13, 2020;Published: November 30, 2020

*Corresponding author: Junesoo Lee, Associate Professor, KDI School of Public Policy and Management, 263 Namsejong-ro, Sejong, Republic of Korea

How to cite this article:Junesoo L, Heung S C, Seungjoo H. Opportunism and Opportunity Cost as Antecedents of Participatory Behavior. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2020; 6(1): 555679. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.06.555679

Abstract

Despite its positive impacts, public participation often begets a representativeness problem due to participants’ opportunism and opportunity cost. Using the survey on 2,000 citizens in South Korea, the research results show that: (1) citizens’ opportunism in terms of self-interest or free-riding may significantly influence their participatory behaviors and (2) citizens’ opportunity costs may act as a mediating factor, i.e., a higher opportunity cost lessens the impact of opportunism on participation. The findings imply that a desirably represented citizen participation can be supported by considering and mobilizing (not manipulating) citizens’ sense of opportunism and opportunity cost.

Keywords:Public Participation; Opportunism; Opportunity Cost

Research Article

Values and impacts of public participation

Citizens may participate in various public venues such as community affairs, market system, and policy process. When it comes to government affairs, citizens can be engaged in policy processes through indirect ways (e.g., voting, donation), collective participation (e.g., participatory budgeting), individual participation (e.g., survey, polls, petition), or conventional channels (e.g., hearing, meeting) [1]. In other words, citizens join governments not only in collective action [2] but also in cooperation for policy decisions [3-6].

As a result of citizens’ active approach to public affairs, many public values are expected to be better achieved. First, in terms of transparency of policy making process, information on public policy issues are further opened [7-12] to help prevent corruption. Second, beyond a simple disclosure of policy information, citizens can have more access to policy-making processes [13-14]. Third, the enhanced openness and accessibility of government also leads to government’s responsiveness to citizens’ demands [2,15,16]. Fourth, public participation eventually helps enhance the legitimacy of policy-making, which is conducive to better policy compliance [17-19].

Motivations of public participation

Beyond the impacts of public participation, why do citizens decide to participate in public affairs in the first place? The motivations behind citizen participation have been studied from various perspectives. The first school of participation motives is concerned with rational choice model. It asserts that people choose to join in political participation by rationally calculating the costs and benefits of their participation [20-23]. However, such cost-benefit approaches have been criticized because of “paradox of participation” phenomena [24] where a rational chooser does not participate in political activities because of the many incentives for free-riding.

Another group of theories on participation motivation is about the (necessary) conditions for participation. People should be available in terms of time and money (i.e. opportunity cost) for them to spare sufficient time to participate [25]. Further, people should be also accessible to public affairs by being a member of social networks through which they can easily participate [25-27]. Exploring more active factors behind participation, there are two types of arguments about the drivers of participation. First, as individual drivers of participation, people tend to participate because of their self-interest. Citizens participate in public matters (1) to avoid sanctions, (2) to receive material extrinsic rewards (e.g., money, social prestige) or intangible intrinsic rewards (e.g., self-satisfaction) [26,28], or (3) to pursue enjoyment of cognitive efforts through participation [29].

Second, as social drivers of participation, people like to engage in public affairs due to (1) political interests [25], (2) distrust in government [30-31], (3) social identity (i.e., desire for inclusion, and aversion to exclusion) [32], (4) social or group pressure [33-36], (5) sense of contribution to social causes [37], and (6) altruism [27]. The last school of participation motive theories focuses more on the conditions for “good participation.” To be successful participants, people should have competence, efficacy, and trust in government [38]. They should also have social and technical skills [39].

Revisiting the motivations of participation

In summary, there are similarities among the participation motivations despite the different formulas and factors of each model. First, people tend to consider and compare the net benefits of participation and non- participation. Second, citizens often hesitate to participate in public affairs because public participation has the characteristics of public goods with externalities. In other words, as the impacts of participatory efforts are shared by the general public, the incentive of participation can be deficient. Therefore, just like other public goods, citizen participation can be over-demanded, under-supplied, and thereby begets a representativeness problem.

From the perspective of public managers who engage citizens in public affairs, this study examines who actually participate and why they participate considering two drivers—opportunism and opportunity cost—which may determine citizens’ participatory behaviors. Simply put, opportunism, as a driver of participation, is a “benefit-oriented” motivation. On the other hand, opportunity cost, as a driver of non- participation, is a “cost-oriented” motivation. By analyzing empirical data on people’s behavior, this study explores how the two drivers influence participatory behaviors independently and simultaneously.

Research Questions & Hypotheses

Participation

As a dependent variable in the research model, three sub-types of participation are considered: participation in community affairs, corporate affairs, and government affairs. First, “participation in community affairs” is often based on public service motivation (PSM), which is “motives and action in the public domain that are intended to do good for others and shape the well-being of society” [39]. The participation in community affairs also include being responsible for and considering the impacts of behavior on nature [40,41]. Having a responsible engagement for future generation is also a part of citizenship for community [42]. Second, “participation in corporate affairs” is usually characterized as responsible consumerism [43] or ethical consumerism to choose ethical brands [44]. Third, “participation in government affairs” is acting as a proponent of legislative or administrative ideas and putting voices into the policy process [45-48]. It also means citizens’ engagement in co-production as information producers or disseminators [49-52].

Opportunism and participation

People’s opportunism is a key independent variable and consists of two sub-items: self-interest and free- riding. First, people may decide to participate in public affairs based on their self-interest expecting the private return of their participation [26,28,53]. Second, as the concept of paradox of participation [24] implies, people may hesitate to participate in public affairs when they think that other people would participate on behalf of them [54]. The arguments on the association between opportunism and participation are hypothesized as below.

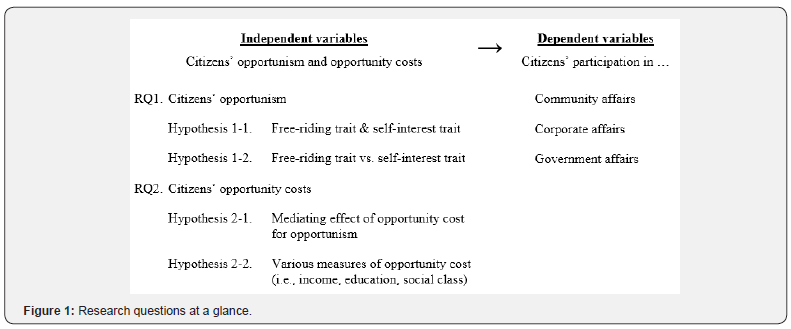

i. Research Question 1: How does citizens’ opportunism influence their participatory behavior?

Hypothesis 1-1. The degree of citizens’ opportunism in terms of “self-interest” and “free-riding” would be significantly associated with their willingness to participate in community, corporations, and government.

Hypothesis 1-2. The degree of citizens’ opportunism in terms of “self-interest” and “free-riding” would be differently associated with their willingness to participate in community, corporations, and government.

Opportunity cost and participation

As another independent variable, peoples’ opportunity cost may also work on their participatory behavior. People’s availability in terms of time and money influences their decision to participate [19,28,55,56]. This time and money play a role not only as actual costs, but also as a perceived cost of participation; thus, it negatively influences participation decisions [53]. Beyond just the simple association between opportunity cost and participation, this study also considers how opportunity costs interact with opportunism via the following hypotheses.

ii. Research Question 2: How does citizens’ opportunity costs mediate the opportunism’s influence on participatory behavior?

Hypothesis 2-1. Given the same degree of opportunism, the degree of citizens’ opportunity cost would be negatively associated with their willingness of participation in community, corporations, and government.

Hypothesis 2-2. The influence of opportunity cost on citizens’ participatory behavior would vary according to the measures of opportunity cost such as income level, education level, and social class.

Methods and Data

Data collection

The data on dependent and independent variables were collected through national survey in South Korea between July 26th and August 6th in 2019. The sampling frame was a nationwide panel over 19 years old of age. The respondents were contacted via mobile phones with a random sampling method. The eventually collected sample size is 2,000.

Measurement and data analysis

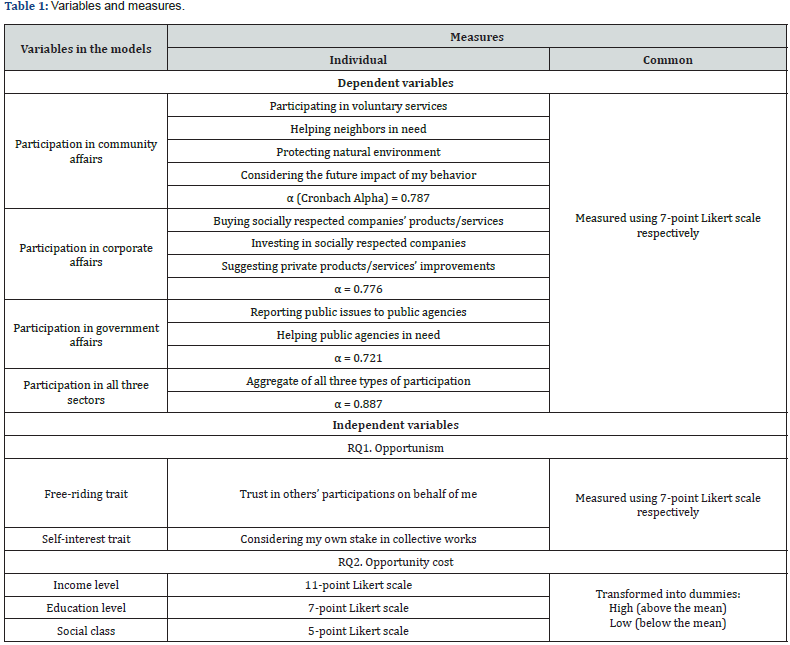

Table 1 shows the three dependent variables—participation in community affairs, corporate affairs, and government affairs—measured by aggregating the individual respondents’ participatory behaviors. The two independent variables were divided into several sub-variables. For instance, “opportunism” was measured by two sub-variables—free-riding traits and selfinterest traits. The “opportunity costs” were measured via three different information sources—income level, education level, and social class. In an attempt to efficiently test the opportunity cost as a mediating variable between opportunism and participatory behavior, the three opportunity cost variables were transformed into dummy variables so that they can be a part of an interaction term (i.e., opportunity cost dummy × opportunism) in the regression models. The three variables of opportunity cost— income, education, social level—signify demographic information of respondents, and thus they played two roles in the analysis as both independent and control variables.

Findings

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables—the correlations between the variables were significant. Interestingly, however, the correlations between opportunity cost and opportunism are very weak and almost insignificant so they look independent of each other—at least statistically. Table 3 shows the model structure and the results of regression analysis. As for the first research question on the association between opportunism and participatory behavior, Hypothesis 1-1 seems to be supported because the statistics show that the “the greater opportunism, the more participation.”

Every coefficient of opportunism (OM) has positive and statistically significant values, and such positive effect is consistent across all types of participation—community, corporates, and government. Hypothesis 1-2 is also supported by the analysis result because the “self-interest” is more associated with participation (i.e., having larger coefficients) than “free-riding” is (regardless of the types of participation). Still, an interesting point in table 3 is that free-riding is positively correlated with participation, although free-riding has been expected, in many literature [24,54], to decrease the willingness to participate. Therefore, the impact of free-riding trait on participatory behavior may need further indepth research.

We can also find the answer to the second research question on the mediating effect of opportunity cost between opportunism and participation. As anticipated in Hypothesis 2-1, given the same degree of opportunism, the statistics show that there is less participation with greater opportunity cost. Such mediating effects of opportunity cost appear only in “self-interest” (not “freeriding”) as opportunism. For Hypothesis 2-2, the coefficients of interaction terms are significant only under the condition of “selfinterest” as opportunism and “income level” as opportunity cost. In other words, the opportunity costs seem to be better defined by income level than by education level or social level.

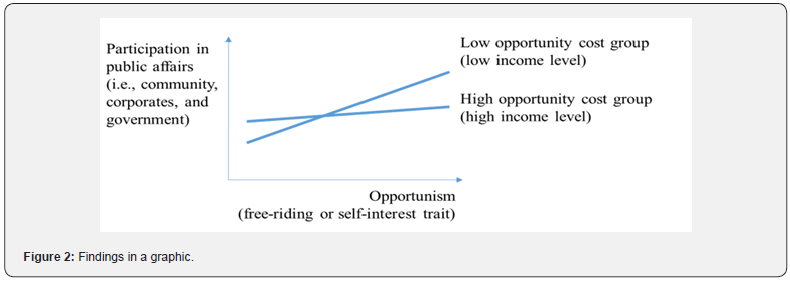

Figure 2 shows the interactive effects of opportunism and opportunity cost on participatory behavior. As the degree of opportunism increases, the likelihood of participation in public affairs (i.e. community, corporations, and government) also rises. When considering the mediating effect of opportunity cost, the group with the higher opportunity cost in terms of income level tends to have less impact of opportunism on participation. In other words, the motivation behind participation (i.e. opportunism) might be significantly influenced by the motivation behind nonparticipation (i.e. opportunity cost) .

Discussion and Conclusion

The core question that this study aimed to answer is “Who actually participates in public affairs and why?” The results answer the question: (1) Citizens’ opportunism in terms of self-interest or free-riding may significantly influence their participatory behaviors, (2) Citizens’ opportunity costs may act as a mediating factor in the association between opportunism and participation, i.e., a higher opportunity cost lessens the impact of opportunism on participation. Based on these findings, the next question of, “Who will participate more?” might be answered as follows: “Those who are more opportunist with low opportunity costs will be more likely to participate in public affairs.” But such characteristics of those who are more likely to participate are challengeable for their opportunist motives of participation and their biased representativeness.

From the perspective of public managers who are responsible to promote a broader (thereby less biased) basis of participation, the findings of this study imply how to mobilize (not manipulate) citizens’ sense of opportunism and opportunity cost. In detail, the attempt to lower the perceived opportunity cost of participation would be synonymous with emphasizing the value of participation relative to other alternatives. It may help citizens to perceive the individual and social efficacy of participation more clearly and vividly. In contrast, the effort of reminding people of the individual and social demerits of non- participation would be another way of influencing people’s perception of opportunity cost. Still, such measures of lower opportunity cost of participation may lead to a higher sense of opportunism, which can again be problematic for the biased representativeness of those with high opportunism. Briefly, the efforts in promoting public participation often presents public managers with a dilemma between a lack of participants and ill-representative participants. With this in mind, future research needs to be conducted on the corrective measures that warrant legitimate representativeness among the participants.

Acknowledgment and Conclusion

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2016S1A3A2924956).

References

- Nabatchi T, Leighninger M (2015) Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy. Jossey-Bass, United States.

- Gaventa J, Barrett G (2012) Mapping the Outcomes of Citizen Engagement. World Development 40(12): 2399-2410.

- Borras SM Jr, FrancoJC (2010) Redistributing land in the Philippines: Social movements and state reformers. In Gaventa J, McGee R (Eds.), Citizen Action and National Policy Reform, UK and New York, NY: Zed, London, pp.69-88.

- OECD(2009)Focus on Citizens: Public Engagement for Better Policy and Services.OECD, Paris.

- SimonsenW, RobbinsMD (2000) Citizen Participation in Resource Allocation. Boulder, CO: Urban Policy Challenges.

- Thomas JC (1995) Public Participation in Public Decisions: New Skills and Strategies for Public Managers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, United States.

- Kim S, Schachter H (2013) Citizen Participation in the Budget Process and Local Government Accountability. Public Performance & Management Review 36(3): 456-471.

- Kweit MG, Kweit (2004) Citizen Participation and Citizen Evaluation in Disaster recovery. American Review of Public Administration 34(4): 354-373.

- Nabatchi T (2012) Putting the Public Back in Public Values Research: Designing Participation to Identify and Respond to Values. Public Administration Review 72(5): 699-708.

- Roberts N (2004) Public Deliberation in an Age of Direct Citizen Participation. American Review of Public Administration 34(4): 315-353.

- Rossmann D, Shanahan EA (2012) Defining and Achieving Normative Democratic Values in Participatory Budgeting Processes. Public Administration Review 72(1): 56-66.

- WamplerB (2012) Participatory Budgeting: Core Principles and Key Impacts. Journal of Public Deliberation 8, Article 12.

- Hadden SG (1981) Technical Information for Citizen Participation. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 17(4): 537-549.

- SeoIY (2014)A Study on Activation Plan of Citizen Participatory Budgeting System: Focusing on Yeosu, Jeollanam-do (Master’s thesis). Korea University, Sejong, South Korea.

- Ebdon C (2002) Beyond the Public Hearing: Citizen Participation in the Local Government Budget Process. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 14(2): 273-294.

- Moynihan D (2003) Normative and Instrumental Perspectives on Public Participation: Citizen Summits in Washington, D.C. The American Review of Public Administration 33(2): 164-188.

- Bingham L, Nabatchi T, O’Leary R (2005) The New Governance: Practices and Processes for Stakeholder and Citizen Participation in the Work of Government. Public Administration Review 65(5): 547-558.

- Ebdon C, Franklin AL (2006) Citizen Participation in Budgeting Theory. Public Administration Review 66(3): 437-447.

- Irvin RA, Stansbury J (2004) Citizen participation in decision making: Is it worth the effort? Public Administration Review 64(1): 55–65.

- Aldrich JH (1993) Rational Choice and Turnout. American Journal of Political Science 37(1): 246-278.

- Downs A (1957)An Economic Theory of Democracy. Harper & Row, New York.

- Jackman RW (1993) Response to Aldrich's Rational Choice and Turnout: Rationality and Political Participation. American Journal of Political Science 37: 279-290.

- TsebelisG(1990) Nested Games: Rational Choice in Comparative Politics. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- OlsonM (1965) The Logic of Collective Action. Schocken Books,New York.

- Verba S, Schlozman KL, Brady HE (1995) Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press,Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

- Alford J (2002) Why do public-sector clients coproduce? Toward a contingency theory. Administration & Society 34(1): 3256.

- van Eijk CJA, Steen TPS (2014) Why people co-produce: Analyzing citizens’ perceptions on co-planning engagement in health care services. Public Management Review 16(3): 358–382.

- Verschuere B, Brandsen T, Pestoff V (2012) Co-production: The state of the art in research and the future agenda. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 23(4): 1083–1101.

- Neblo MA, Esterling KM, Kennedy RP, Lazer DM, Sokhey AE (2010) Who wants to deliberate—and why? American Political Science Review 104(03): 566–583.

- Hibbing JR,Theiss-Morse E (2002) Stealth Democracy: Americans’ Beliefs about how Government Should Work. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- John P, Fieldhouse E, Liu H (2011) How civic is the civic culture? Explaining community participation using the 2005 English Citizenship Survey. Political Studies 59(2): 230–252.

- Hafer JA, Ran B (2016) Developing a Citizen Perspective of Public Participation: Identity Construction as Citizen Motivation to Participate. Administrative Theory & Praxis 38(3): 206–222.

- Gagne M, Forest J, Gilbert MH, Aube C, Morin E, et al. (2010) The motivation at work scale: Validation evidence in two languages. Educational and Psychological Measurement 70(4): 628– 646.

- Millette V, Gagne M (2008) Designing volunteers’ tasks to maximize motivation, satisfaction and performance: The impact of job characteristics on volunteer engagement. Motivation and Emotion 32(1): 11–22.

- Schmidthuber L, Piller F, Bogers M, Hilgers D (2019) Citizen participation in public administration: Investigating open government for social innovation. R&D Management 49(3): 343- 355.

- Weinstein N, Ryan RM (2010) When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98(2): 222–244.

- Bovaird T, Stoker G, Jones T, Loeffler E, Roncancio MP (2015) Activating collective co- production of public services: Influencing citizens to participate in complex governance mechanisms in the UK. International Review of Administrative Sciences 82(1): 47–68.

- Cooper TL, Bryer TA, Meek JW (2006) Citizen-centered collaborative public management. Public Administration Review 66(s1): 76–88.

- Perry James L, Hondeghem Annie (2008) Building Theory and Empirical Evidence about Public Service Motivation. International Public Management Journal 11(1): 3–12.

- Portney Kent E(2015)Sustainability. The MIT Press.

- Sachs, Jefferey D (2015) The Age of Sustainable Development. Columbia University Press.

- Hoskins Bryony L, Mascherini Massimiliano (2009) Measuring Active Citizenship through the Development of a Composite Indicator. Social Indicators Research 90(3): 459-488.

- Davenport K(2000) Corporate Citizenship: A Stakeholder Approach for Defining Corporate Social Performance and Identifying Measures for Assessing it. Business and Society 39(2): 210-219.

- Zadek Simon (2001) The Civil Corporation. Earthscan.

- Barg CJ, Miller FA, Hayeems RZ, Bombard Y, Cressman C, et al. (2017) What's involved with Wanting to be involved? Comparing expectations for Public Engagement in Health Policy across Research and Care Contexts. Healthcare Policy 13(2): 40–56.

- Kimball J(1997) NGOs Make an Important Contribution to Policy Development. Public Management Forum3(3). OECD.

- Li KK, Abelson J, Giacomini M, Contandriopoulos D (2015) Conceptualizing the use of public involvement in health policy decision-making. Social Science & Medicine 138(1): 14–21.

- O’ConnellB (1994) People Power: Service, Advocacy, Empowerment. Foundation Center.

- Alford J (2009) Engaging public sector clients: From service-delivery to co-production. Springer.

- Coston J (1998) A Model and Typology of Government-NGO Relationships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 27(3): 358-382.

- Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, Carroll JK, Irwin A, et al. (2013) A New Dimension of Health Care: Systematic Review of the Uses, Benefits, and Limitations of Social Media for Health Communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research 15(4): e85.

- Park H, Reber BH, Chon M (2016) Tweeting as Health Communication: Health Organizations' use of Twitter for Health Promotion and Public Engagement. Journal of Health Communication. International Perspectives 21(2): 188–198.

- Whiteley PF (1995) Rational Choice and Political Participation. Evaluating the Debate. Political Research Quarterly 48(1): 211-233.

- Muller E, George Klosko, Karl-Dieter Opp (1987) Rebellious Collective Action Revisited. American Political Science Review 81(2): 561-564.

- King CS, FelteyKM, O’Neill Susel B (1998)The question of participation: Toward authentic public participation in public administration. Public Administration Review 58(4): 317–326.

- Lowndes V, Pratchett L, Stoker G (2006) Diagnosing and remedying the failings of official participation schemes: The CLEAR framework. Social Policy and Society 5(2): 281–291.