Urban Poverty, Discrimination, and Fragmented Landscapes: Recasting ‘Le Grand Paris’ Urban Renewal Proposal for Territorial Integration

Edad Mercier*

Department of World History, St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, St. John’s University New York, United States

Submission: November 10, 2020;Published: November 23, 2020

*Corresponding author: Edad Mercier, Department of World History, St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, St. John’s University, New York City, United States

How to cite this article:Edad M. Urban Poverty, Discrimination, and Fragmented Landscapes: Recasting ‘Le Grand Paris’ Urban Renewal Proposal for Territorial Integration. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2020; 6(1): 555678. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.06.555678

Abstract

This paper is a qualitative urban ethnographic study of Black and Arab youth, and the effects of poverty in Seine-Saint-Denis and the 18éme arrondissement. The work concerns individual and group attitudes on ‘affinity,’ ‘placemaking,’ and ‘discrimination’ vis-à-vis the 2007 ‘Le Grand Paris’ urban renewal proposal. The youth included in the study are members of two community-based organizations—Association Le Club Barbés in the 18éme, and Association Youth in Movement (Jeunesse en Mouvement-JEM) in Seine-Saint-Denis. Through Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), direct participant observation, go-along, semi-structured, open-ended, and face-to-face interviews between 2013 and 2014, I collected 15 participant interviews and 7 expert interviews. I identified four identity-forming narratives from my participant interviews: (1) placemaking through affinity bonds; (2) schools as boundary making; (3) navigating violence between worlds; and (4) self-esteem through leadership. These narratives strongly suggest that youth participation in civic associations is correlated with a greater level of individual and group efficacy.

Keywords:Symbolic Boundaries; Poverty; Civic Participation; banlieues/banlieusards; Youth; Race/Ethnicity

Research Article

In 2007, the former President of France Nicolas Sarkozy announced plans to create ‘Le Grand Paris’ –the largest urban renewal initiative ever proposed for an urban conglomerate within the European Union. The proposal was a 30-year vision for the redevelopment of Paris and the city’s banlieues or suburbs, Hauts-de-Seine (92), Seine-Saint-Denis (93) and Val-de-Marne (94) via expanded transportation options (Grand Paris Express, 72 new train stations), new housing construction (70,000 housing units, each year for 25 years), and more connected public facilities (204 km of new railroad tracks). The centerpiece of Le Grand Paris project was the new housing construction to alleviate housing demand and reduce poverty in inner Paris. Thirty percent of this annual housing construction would be public housing. The Duflot Law [1], which coincided with plans for Le Grand Paris, stated that “no new rental contract [would] be permitted to charge more than 20 percent per square meter above the neighborhood’s median rent, which [would] be assessed annually by a ‘local rent observatory’” [2]. The purpose of Le Grand Paris project was ultimately to: (1) Improve the lives of residents living in the greater Paris region; (2) Reduce socioeconomic inequalities between the territories of Le Grand Paris; and (3) Create a sustainable urban development model replicable in other parts of France [3].

Two years before Sarkozy’s 2007 public announcement about Le Grand Paris, Seine-Saint-Denis (93), the poorest suburb, faced one of the largest riots in recent French history called, les émeutes des banlieues de 2005, or the suburban riots of 2005. The violent deaths of two French teenagers Zyed Benna (Tunisian descent), 17, and Bouna Traoré (Mauritanian descent), 15, electrocuted to death while running away from police officers in Clichy-sous-Bois, precipitated the 2005 riots. The violence spread to almost 274 towns across the country, where schools were defaced, and cars set ablaze (“Riots in France”, 2005). President Sarkozy later called the youth rioting “outcasts” and an “extreme minority” trying to ruin the country (“Nicolas Sarkozy continue de vilipender ‘racailles et voyous’”, 2005). The 2005 rioting set up much of the context for Le Grand Paris proposal in 2007. The proposal was at once a symbol of unification and a step towards solving the deep economic disparities between the suburbs of Paris and ‘Paris proper.’ A declinist reading of the 2005 unrest would suggest Black and Arab communities would remain marginalized in the context of Le Grand Paris plans. Nevertheless, my work shows that peerto- peer links and positively affirming group involvement were the main factors that facilitated civic engagement among young people in Paris and its suburbs following the 2005 riots—alongside a greater willingness to engage with Le Grand Paris proposal.

Data Collection

The methodology of this paper is qualitative urban ethnographic research via multiple case study analysis, completed through a methodological triangulation of data sources: semistructured interviews, direct observation and critical discourse analysis of media archives and public documents. I conducted semistructured interviews to capture the narratives of banlieusards of Seine-Saint-Denis (ages 18-40). This narrative angle lends itself to a thick analysis of the interplay between structures and actors; and opens the door to exploring how observable boundaries are potentially reproduced or weakened. During my six weeks of field research in Paris and Seine-Saint-Denis, I expanded my participant pool to include youth (also 18-40) living in the 18éme arrondissement of Paris, which is considered a “quartier de banlieue,” because of the high concentration of low-income ethnoracial minorities living there.

Intertextual Analysis

The premise of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is that language is a “social act” that reveals ideological assumptions and power paradigms [4]. In the early 1980s-90s, Fairclough [4], van Dijk [5] and Wodak [6] established the framework for CDA that included intertextual and media analysis. Newspaper headline analysis is an important strategy in CDA because headlines serve as early signaling devices for the reader [7]. Ramagundam [8] contended that newspaper headlines were a lens into the “responsive mechanism” of a state or society to an event. I designed a CDA of 93 pages of Le Monde newspaper articles in the 2100 days before and after the 2005 riots in France using Le Monde archival search engines. Initially, I searched for the phrase “Seine-Saint- Denis” in headlines. Then, I added “banlieue” into the keyword search. My intervening question was: how was Seine-Saint-Denis and its residents characterized before and after the 2005 riots by the mainstream French press?

Interviews

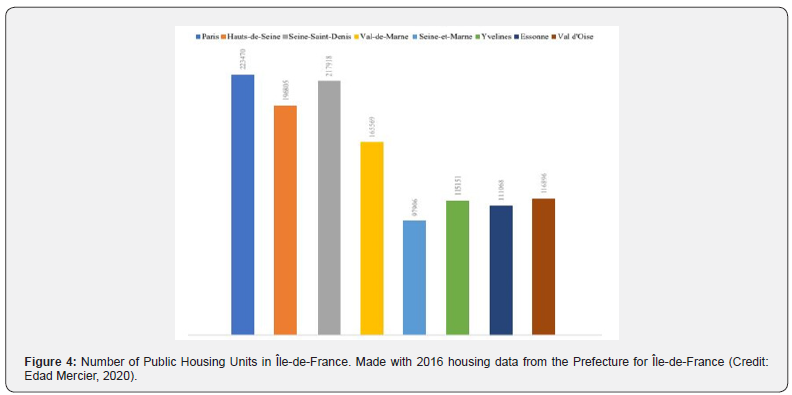

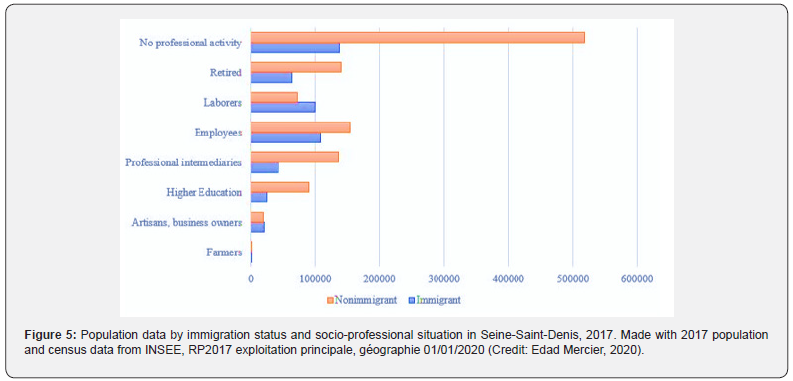

The second part of my methodology was field research. I spent roughly 200 hours in the 18éme arrondissement in Paris and Seine-Saint-Denis, between 2013 and 2014, completing direct observation and go-along on five, separate occasions with young people between the ages of 18 and 40 years old. I conducted 15 face-to-face, open-ended, and semi-structured interviews with members of Jeunesse en Mouvement and Club Barbés. Fourteen were conducted in French and one in English. The survey that I designed consisted of 19 open-ended questions that were translated from English to French. Responses were documented through handwritten notes and audio recordings. One participant declined to be audio recorded2. The interview recordings were transcribed and analyzed for recurrent themes. In addition, I conducted seven expert interviews with individuals, who work on issues concerning urban poverty, policing, and spatial segregation. In total, I collected 22 interviews. Semi-structured and openended interviews were appropriate for this study because they help establish rapport through a “conversational” approach while eliciting rich data [9]. My first set of interviews and observations were with the members of Jeunesse en Mouvement (JEM). Founded after the 2005 riots in Seine-Saint-Denis, the purpose of JEM is to improve the national image of banlieusards through cultural and civic activities. The organization also seeks to enhance the employability of youth in Seine-Saint-Denis through job training. JEM is entirely youth-led and managed through fundraising and local community development grants. At 91.12 square miles, Seine-Saint-Denis is almost double the size of Paris. Approximately 1.6 million people live in Seine-Saint-Denis [10]. Several towns within Seine-Saint-Denis, such as Saint-Denis, Saint-Ouen, Aubervilliers and Argenteuil, are priority security zones, Zones de Sécurité Prioritaires (ZSP). JEM’s offices are in Épinay-sur-Seine, a commune of Seine-Saint-Denis. Épinay-sur-Seine is largely comprised of Black and Arab residents. The unemployment rate in Épinay-sur-Seine in 2019 among 15 to 64-year olds was around 15 percent [11]. Of all the banlieues, Seine-Saint-Denis contains the most public housing. Public housing in France is largely administered by a combination of state-controlled Habitation à Loyer Modéré (HLM) organizations and Société d’économie mixte (SEM), or semi-private organizations—all under the auspices of the Ministry of Housing and Finance (Social Housing Country Profile, n.d.). Seine-Saint-Denis has the highest number of public housing units of all the banlieues: 217 918 (Seine-Saint-Denis); 196 805 (Hauts-de-Seine); 165 569 (Val-de-Marne); 97906 (Seineet- Marne); 115 151 (Yvelines); 111 068 (Essonne); 116 896 (Val d’Oise) (“Dossiers : Les chiffres de la région Île-de-France”).

My next set of interviews and observations were with Club Barbés. Club Barbés is a youth academic and social support center. It is a ‘safe space’ for youth living in the 18éme to meet and participate in civic and cultural activities after school. The 18éme district borders Seine-Saint-Denis. It is also home to the Goutte d’Or, (“Drop of Gold”) neighborhood. The Goutte d’Or has the highest concentration of Sub-Saharan African and North African immigrants/children of immigrants in Paris. In Paris, 58 percent of public housing units can be found in 4 districts: 13éme, 18éme, 19éme, 20éme. The 18éme, 19éme and 20éme districts comprise the Goutte d’Or. The 18éme is also considered one of the undesirable parts of Paris because of the high poverty rates. The poverty rate in the 18éme was around 21 percent in 2017, compared to the overall poverty rate in Paris which was 15.2 percent in 2017 [12].

Foot note

1Author email: edad.mercier20@my.stjohns.edu

2Participants also signed waivers consenting to the interview, publication, and objectives of the study.

The aim of my empirical research was neither to represent the attitudes of an entire population through sampling nor to represent the views of a community. Rather, my objectives were to (1) capture the narratives of a subset of the banlieusard and ethnic minority population in Paris on violence and stigmatization; (2) understand how proximity to “city center” impacted feelings of self-worth; and (3) analyze the role of community-based organizations in changing opinions on civic participation, notably around Le Grand Paris project.

Disaffiliation and Socioeconomic Inclusion

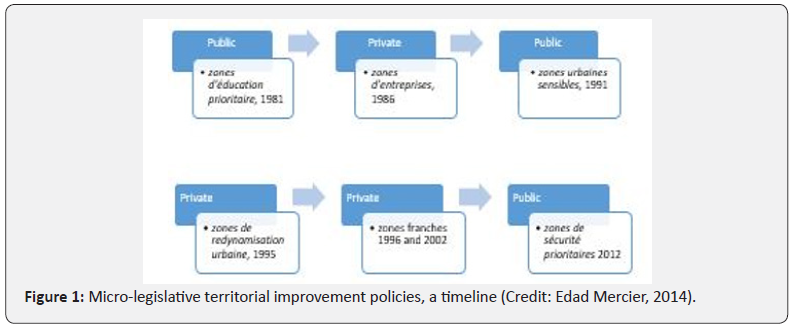

Territorial economic improvement policies for poverty reduction have served as proxies for race-oriented social policies in France. Examples of micro-legislative territorial economic improvement policies include zones d’entreprises in 1986, zones urbaines sensibles in 1991, zones de redynamisation urbaine in 1995, zones franches in 1996 and 2002, zones d’éducation prioritaire in 1981, and zones de sécurité prioritaires in 2012. However, memories of violence and commemorative practices surrounding that violence, which play out in the press, all circumscribe these legislative policies aimed at territorial development—Le Grand Paris urban renewal law and proposal included. In Black Skin, White Masks [13] Frantz Fanon was one of the first postcolonial political philosophers and psychiatrists to argue that colonial violence created a system of intellectual, social, and physical oppression, which Black and Brown people internalized (Figure 1). Modern work by French historian Pap Ndiaye highlights how the legacies of colonial violence and racism permeate political discourse and institution building in France, making it difficult for Blacks and other minorities to achieve social recognition [14]. French sociologist Dominique Duprez argued that social isolation, job precarity, and favoritism in hiring make it difficult for minority youth to feel a sense of affinity in France: “Exclusion therefore appears as the outcome of a process of precariousness that goes from integration to vulnerability, and from vulnerability to social inexistence. Disaffiliation is a way of talking about the loss of status” [15]. In his research on Arab and North African youth in Lille in the 90s, Duprez found that socioeconomic disaffiliation often led to “negative” individualism or a quasi-nihilistic worldview that attempting to succeed in school or getting a “good job” was exceedingly difficult and ultimately a waste of time [15]. Not everyone subscribed to this “negative” individualism though. Some of the young people in his study valued school and sought visible leadership roles (radio host, children’s programming, etc.) to overcome the stereotypes (vagabond, reckless, etc.) associated with North Africans and Arabs in France [15]. Mehta’s essay “Negotiating Arab-Muslim Identity, Contested Citizenship, and Gender Ideologies in the Parisian Housing Projects: Faïza Guène’s Kiffe kiffe demain [16] asserts that the crisis of disaffiliation also takes on gendered dimensions for minority youth struggling to integrate into ‘mainstream’ France. Public housing in the banlieues, specifically, is the main site of intense conflict over beur3 identity and belonging—especially for women and girls: “The social confines of the housing projects delimit gender roles in a social exclusion/ gender seclusion parallel… ‘certain Muslim girls must navigate an additional layer of gender constraints attached to competing home, neighborhood, and school expectations’ “ [16].

Foot note

3Initially considered a slang term in the 1970s and 1980s for people of North African origin or the Maghreb, beur is now used to explain a bicultural identity that is both French and Arab.

Many of the territorial improvement policies in France aimed at combatting poverty and promoting social inclusion have concentrated on supporting vulnerable students from zones d’éducation prioritaire (ZEPs) living in public housing. La loi pour l’égalité des chances [17], a direct response to the riots of 2005 in the banlieues, instituted a series of measures including academic preparatory classes for ethnic minority students (les jeunes issus de minorités visibles) in ZEPs for admissions into elite institutions. On preparatory classes for ZEP student recruitment at the competitive Sciences Po, Political Science Professor Daniel Sabbagh argued that the measure would not be enough to combat social exclusion: the majority of “ZEP students [are] full-fledged French citizens, but the fact that a fair number of them often are not treated as such on account of their foreign (North African) extraction is precisely one of the factors that account for their being disadvantaged in the first place…yet…it is plainly impossible for [Sciences Po officials] to ascribe to these students’ purported ‘culture’ any specific content”[18].

Indeed, policymakers in France have struggled for decades with how to integrate ‘immigration cultures’—notably immigration cultures from the former colonies of France—into the “indivisible, secular, democratic and social Republic”[19] through schooling, housing, and health services, without being castigated as extremists. Le Grand Paris, thus, as an extension of La loi pour l’égalité des chances, has as its purpose the goal of integrating all citizens “regardless of their origin, race or religion” (France Diplomacy-Secularism and Religious Freedom, n.d.) into France—not only through social policies, but also through physical improvements to transport and housing. Thus, perhaps making the obvious lines separating local identities—poor and rich, educated and uneducated, young and old, ethnic minorities and whites—somewhat more blurred.

Commemorative Practices in The Discursive Landscape

The notion of spatial and narrative identities originates from Henri Lefebvre’s seminal work on “le percu” (perceived space), “le concu” (conceived space) and “le vecu” (lived space) in the Production of Space (1974), and Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s work on the relationality of space in the Phenomenology of Perception (1945). Downs and Stea (1977) also argued that humans produced spatial knowledge and cognition through a series of haptic (touch) and pictorial (visual perception) experiences. Over time these experiences produced a “body” map of knowledge that directed individuals on where to reside, socialize and work. For the banlieusards and young ethnic minority residents of the 18éme in my study, stigmatization resulting from discrimination based on ethnicity, ‘zip code,’ poverty, and over-policing, frequently interfered with the way they were able to communicate information about themselves to non-members of their voluntary associations. People sometimes feigned interest in the organizations or shrugged the groups off as one of the many civic associations in France. Nevertheless, these organizations represented the only opportunities for my study participants to take on leadership roles (like teaching, cooking, radio programming, and field trips), commemorate, and recognize group and individual achievements (i.e. opening a new office space, receiving grant money for a project, graduating from school)—these acts of commemoration and recognition often surpassing external approval or validation.

In his essay “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire” (1989), Pierre Nora wrote that memory was a “perpetually actual phenomenon, a bond tying us to the eternal present” [20]. Nora explained that museums, cemeteries, books, and library archives are deliberate acts of commemoration chosen with the goal of shaping eventual historical narratives [20]. For example, the French revolutionary calendar became a frame of reference for older generations. Classroom manuals were the object of memory rituals as well [20]. The Tour de la France par deux enfants (1877), an influential geography schoolbook for children, appealed to the memory of adults for a France that no longer existed following the Franco-Prussian war [20]. Nora suggested that material sites for commemoration increasingly existed because real environments of memory no longer existed: “there are lieux de mémoire, sites of memory, because there are no longer milieux de memoire, real environments of memory” [20]. On modern archival methods, Nora wrote that the “materialization of memory” has been democratized to the point that people are encouraged to record everything and produce archives even when they are not sure what they are preserving [20]. This democratization of information and archiving has led to public clashes on the meaning and significance of national events. For example, the deliberate use of specific words, such as “hooligans,” “outsiders,” and “immigrants,” by the French press (Le Monde) to characterize and memorialize events following the 2005 riots incensed many, but also left a rich archive of articles documenting the emotional work underway to rebuild Paris and the banlieues. Oftentimes what is “forgotten” is also equally important as what is “remembered” in public discourse. In “Memory, Cultural Transmission and Investments,” [21] Dessí argued that beliefs formed about institutions by the younger generation were largely impacted by memories received from older generations. Dessí emphasized that societies developed selective memory based on what information was likely to produce positive externalities in the future. The goal was to “foster optimism” by avoiding information that represented “bad news” [21]. Regime change (i.e. East and West Germany) could also lead to changes in collective memory to assign new values [21].

Critical Discourse Analysis of the 2005 Unrest in Le Monde Articles

In this study of Le Monde articles, my findings suggest that media discourse on the banlieues prior to the 2005 unrest was biased and reconstructed hegemonic narratives of second-class citizens by reproducing the same phraseology to maintain unequal territorial, social, and class dynamics. In the 2100 days before the 2005 unrest, Le Monde journal released thirty articles that referenced Seine-Saint-Denis in the headlines with the word, “banlieue,” in the body text. In the thirty articles, Seine- Saint-Denis was associated with the words: “exclusion,” “crime,” “misery,” “anti-white,” “unstable,” and “extreme4.” Wacquant [22] assessed that spaces frequently demonized by the press or politicians as corrupt or downtrodden, often led to extreme marginalization and subjugation for the people who inhabited those same spaces. For “when these ‘penalized spaces’ [23] are, or threaten to become, permanent fixtures of the urban landscape, discourses of vilification proliferate and agglomerate about them, ‘from below’, in the ordinary interactions of daily life, as well as ‘from above’, in the journalistic, political and bureaucratic (and even scientific) fields” [22]. This creates a category of stigma that is demarcated by race, class, and geography—sometimes visible through gestures and daily practices, but frequently inscribed into memories, affects and senses related to belonging versus strangeness. Positive references to Seine-Saint-Denis in Le Monde journal, before the unrest, appeared in articles associated with entertainment. Positive association words included, “creative,” “worldly,” “effervescent,” and “cultural exchange.” However, these positive association words were typically employed to exoticize events (i.e. Africolor festival) and the invited (often foreign) entertainers. Following the 2005 unrest, some of the language referring to Seine-Saint-Denis in Le Monde took on a reconciliatory tone that made explicit reference to the “unfair” characterizations of residents of ‘93’. Certain articles called on policymakers to find the “voice” of banlieusards by investing in creative writing and artistic expression in the banlieues. Several articles referenced the importance of job training for women in the ‘93’. Another article from 2011 cited the collective “euphoria” of elected officials regarding the extension of a transit line into Seine-Saint-Denis as part of Le Grand Paris Express—hopefully making the ‘93’ a “new center of gravity for the Île-de-France region” [24]. These results suggest that media discourse shifted from a narrative of territorial hegemony and control to discussion on personhood, agency, community cohesion, social welfare, and holistic well-being.

Field Notes from Interviews and Thematic Analysis

Most of my interviewees struggled with visualizing a viable future in their current neighborhood. Wishes to acculturate or take on the social modes and customs of older professionals in Paris proved difficult. A lack of models and external support structures to gain entry into attractive careers in journalism and business—fields which some interviewees expressed an interest in—led most to return to their childhood communities, somewhat reluctantly, to renew old social bonds in the hopes of creating something new.

Foot note

4Le Monde newspaper online archival research, 2005.

Several of my study participants recounted experiences of symbolic and physical violence [25] when trying to circulate in and around Paris. Said violence, in all instances, came from police forces and usually occurred spontaneously and was intrusive socially and physically. The unpredictability or uncertainness of traveling in Paris contributed to feelings of isolation, surprise, and hurt, making it extremely difficult for participants to forge new paths or customs outside of their childhood or adolescent patterns of networking and socializing. For all, the social-emotional relational attachments from peer-to-peer networks contributed to feelings of positive motivation and self-esteem, despite police violence (Figure 2).

1. placemaking through affinity bonds;

3. navigating violence between worlds;

4. self-esteem through leadership

My first interview was with Lucas, a leader in the association JEM. Lucas, 26 years old and of Black French Caribbean descent, was born and raised in Seine-Saint-Denis. We met at a café in the 6éme, a more convenient location for him that day. When we met, Lucas was actively seeking new employment opportunities in Paris. I asked him about the aspects of his neighborhood in Seine-Saint-Denis which he enjoyed the most, to which he replied the good, cheap food and the cinemas—but for “really going out,” Paris was the place to be: ‘Despite the new stuff going on here [my neighborhood], it’s really a place to sleep, eat. To really go out, for me, it’s Paris. I go to Saint Michel, Oberkampf, Chatelet or Bastille. The problem is if you meet friends at Épinay, it’s only going to be people from Épinay. If you see other people, outside of the area, Paris is better because then you will meet people from all over.’ (Lucas, Male, 26). Lucas clarified that Paris was not an easy place to “hang out” in, because of racial profiling:‘When I go into stores in Paris, the staff look at my clothes and sneakers and they make assumptions about what I can and can’t afford. Regular stores will check my ID, bags, and pockets, before I can even step inside. I look around and this is only happening to me because I am black.’ (Lucas, Male, 26) (Figure 3).

On whether he would prefer to shop and run errands in Seine- Saint-Denis to avoid the hassle of Paris, Lucas said he would, but that there really was not much for young people to do in the area. I asked Lucas about the town hall in Épinay and if local officials were helping young people in his neighborhood. He quickly made it clear that the town hall in Épinay did not plan much for young people: ‘There is an annual hip hop festival… outside of this festival, the artists who come and perform at Épinay are more for the welloff classes, the classes who vote for the mayor. I think there is a cleavage between young people of the city and the municipality… there are youth with lots of potential who could do a lot of things but they don’t like the mayor so they don’t want to.’ (Lucas, Male, 26). When I asked Lucas about why he decided to invest his time and efforts in JEM, he explained: ‘I like my city, even though I don’t like the mayor, I like my city…I continue for personal reasons…I want my area to change.’ (Lucas, Male, 26). And how about Le Grand Paris—would that change his daily habits, especially given the fact that Paris was usually his preferred destination for hanging out with friends? ‘For youth of the banlieue, like me, [Le Grand Paris] is somewhat of a side issue, we don’t speak much about it, we haven’t really studied this domain…it’s still in the abstract…But I will tell you that when I go outside of Paris or abroad, I tell people that I am from Paris…because it’s simpler for people…and it’s more reputable.’ (Lucas, Male, 26). I gave Lucas more details about Le Grand Paris—its scope and objectives—and Lucas replied: ‘The idea is good, but we have to see concretely what repercussions this will have on us…Nice words, but concretely, what is going to happen.’ (Lucas, Male, 26).

Foot note

5All names of interviewees have been changed to protect privacy. The selected interviews were transcribed from French to English by the author from recordings

1. placemaking through affinity bonds;

4. self-esteem through leadership

Later, I met with Amar. Amar is 26 years old, Black and of Senegalese origin. He is also friends with Lucas and one of the leaders of JEM. He was born and raised in Seine-Saint-Denis and continues to reside there. Amar requested we meet at a café in a recently developed shopping mall in Épinay because of its convenient and nice surroundings. At the time of the interview, Amar had completed his studies at Université Paris XIII and was working with JEM on organizing a youth-led radio station called New-Vo Radio. As we searched for a spot to sit in the café, Amar told me that he was surprised that I was in Épinay. I asked him why, and he said that people usually never come to Épinay, because of its bad reputation: ‘People refuse to come to Épinay, they think there is a lot of delinquency and they have a lot of prejudices against the area…they think it is frightening and that it’s the bad part of the banlieue.’ (Amar, Male, 26). Amar added that the stereotypes were unfortunate, because “[Épinay] is a good area to live in” … But as a young person growing up in Épinay, were there activities for young people to get involved in? ‘From 0-16 years old a young person in ‘his’ neighborhood has lots of activities, from 16-30 years of age there is nothing for him…Either that person falls into playing computer games and you don’t even know they exist, or they fall into delinquency.’ (Amar, Male, 26).

Amar clarified that personally he “never asked the town hall for anything” because he knew not to expect much. Well why invest time in JEM? ‘Old people from my building used to tell me about the history of Épinay and I liked it…The story of Épinay is a story of great writers, such as Rousseau who came to live here. It’s a town of great historical figures, dukes, counts, who came to live here…It is also a town of liberation, many people died for France here. It’s also a city of light, a city of theater.’ (Amar, Male, 26). I finally asked Amar about Le Grand Paris, and he stated that he had heard a few things about the project ‘here and there.’ He concluded that it could be a good idea if everyone were included in the planning of the project.

1. placemaking through affinity bonds;

3. navigating violence between worlds

After speaking with Amar, I met with Christine. Christine is 25 and Black of Congolese origin. Christine requested that we meet at the newly opened offices of JEM in Épinay. When we met, she was looking for different vocational internships to complement her studies. I asked her to describe the aspects of her neighborhood [Lamentin] that she liked, and she said that she appreciated the “calm,” mainly because there was not too much to do: ‘For those under 16, there are sports. But if for example you don’t do sports there’s not a lot of things for you to do…There’s not enough infrastructure for the youth.’ (Christine, Female, 25). She noted that as a young person it was important to be “creative.” On traveling between Paris and Épinay, Christine explained that the atmosphere could change dramatically. While Épinay could be “calm” because there was not too much to do, Paris was always swarming with people to the point of being overwhelming. I asked Christine to explain a bit more about her impressions of Paris, and she recounted a violent incident with the police while waiting in Château Rouge for a family member: ‘I was stopped by a police officer—by police officers…I was in the wrong area at the wrong time…I had my bag on like this, and someone grabbed my bag! I thought it was a thief at first. Fortunately, I did not react, because it was a police officer, who wanted to seize my bag because he thought I was going to sell [drugs] …And then his colleagues arrived. So, I had three police officers around me…The people around me on the street who saw were like ‘aww, how could the police do that?’…I also told this to the mother of a friend and she said that I should have taken their ID numbers and gone to the police commissariat, because the police did not have the right to do that…and I agreed with her, but I was in a hurry and …I was waiting for someone…it was the wrong neighborhood, at the wrong time.’ (Christine, Female, 25). I then asked Christine if she now avoided Château Rouge because of the incident and she replied: ‘It’s not a neighborhood that I necessarily appreciate, but there are many exotic African shops…there are always police there…At Château Rouge, you can’t avoid them.’ (Christine, Female, 25). When I asked Christine if an incident like this with the police in Château Rouge kept her away from Paris, she explained that with family and friends in Paris, plus the shopping in Château Rouge specifically catering to African customers, it was almost impossible to just stay in Seine-Saint-Denis. Christine also explained that she thought Le Grand Paris was a good idea, especially the Grand Paris Express train, because the banlieues were so underserved by the metro system. She later recalled stories from friends who struggled with job interviews when employers asked if they had the means to travel to work.

1. placemaking through affinity bonds;

3. navigating violence between worlds; and

4. self-esteem through leadership

Around the same time as my interview with Christine, I met with Omer. Omer is 30 years old, Arab of North African origin, and a member of JEM. Omer was interested in journalism and discussed some of his projects with me. I asked him about his overall experiences traveling and working in Paris and he brought up the frequent identity checks (Contrôle au faciès) targeted towards minorities. The identity checks, which might involve a pat-down, checking valid train tickets and IDs, are frequently conducted by the French national police (Zagrodzki 2012). Around 2011, several nonprofit organizations launched a movement called “Stop Identity Checks” which urged victims of these aggressive identity checks to record the incidences and file a claim with local justice officials. Omer explained that the identity checks made Paris a difficult place to feel comfortable and live in: ‘The police will usually stand outside the metro and do identity checks when everyone is exiting. That is how they catch people.’ (Omer, 30, Male). Paris, while discomforting because of the street harassment and police abuse, was still the ideal meet up spot for young people from Seine-Saint-Denis because of the location and ease of transport. Going back ‘home’ to Seine-Saint-Denis usually meant seeing old, familiar faces—but not much else in terms of professional development opportunities. JEM was trying to change this by creating a support base for young people wanting to invest in themselves and their communities without having to travel for hours on unreliable transport, where they might be stopped and frisked.

During our conversation, I asked Omer if Le Grand Paris would change how he felt about working in Paris, regardless of the police presence, and he replied ‘I’ve heard of Le Grand Paris, but what will it mean for daily life?’ (Omer, 30, Male).With so many Black and Arab youth living far from the city center and transport being unreliable, Omer thought Le Grand Paris was promising, but only if associations like JEM could be involved—that would make the plan a bit more tangible.

1. placemaking through affinity bonds;

2. schools as boundary making;

4. self-esteem through leadership

During one of JEM’s community meetings, I spoke with Patricia. Patricia is 26 years old, Arab of Algerian origin. Patricia was finishing up her graduate studies in business when we met. Patricia recalled the challenges of completing her graduate research—market research on the Halal restaurants and groceries in Paris—mainly because it was difficult to find mentors or people willing to work with her. Her graduate research grew out of her own experiences shopping for Halal food:‘Sometimes there are places that say they are ‘Halal’ or food that is labeled Halal, but it is not the truth. It’s made shopping difficult in Seine-Saint-Denis and Paris.’ (Patricia, 26, Female). Patricia expressed liking the social downtime at JEM and seeing friends; but wished there could be more job opportunities available especially since she was about to graduate. For her, Le Grand Paris, sounded like an excellent idea, but with little details on when it would start or how to get involved it was hard to visualize.

1. placemaking through affinity bonds;

2. schools as boundary making;

3. navigating violence between worlds; and

4.self-esteem through leadership

Leila is 20, Black and Muslim and a member of Club Barbés. She is second-generation Malien-French. She grew up in the 18éme. When we spoke, she was studying to become a social worker. I asked Leila to describe her neighborhood, and she described some of the good and bad aspects: ‘It’s cosmopolitan, ça bouge…it’s also a difficult neighborhood because we are a ZUS… in Château Rouge people leave the banlieues just to buy African products here.’ (Leila, Female, 20). I asked Leila to explain in more detail what she liked and disliked about the 18éme: ‘We are a little bit of a quartier banlieue. We are in Paris, but at the same time we have the impression of being in a banlieue, where you see young people hanging around in bars, who don’t go to school who play around with drug trafficking and prostitution…me, I grew up on a street with a lot of prostitution…I have a lot of friends who took the path of delinquency…some returned to school…but [crime and drugs] have an impact on young people here.’ (Leila, Female, 20). On the impact of joining Club Barbés, Leila described how it taught her to be “responsible” and “independent.” She discussed how it made her feel like she had a place in society: ‘The objective of the president [of the Club] was that we succeed in school…We are children of immigrants, and our parents don’t have the time or means to take us to museums or on trips.’ (Leila, Female, 20).

Pétonnet’s ethnographic research on the banlieues of Paris in the 1980s revealed that residents often felt a sense of shame about their neighborhoods, which would cause many to avoid revealing where they live. Despite being in Paris, Leila described how living in the 18éme still made her feel ashamed, almost like an outsider living in Paris: ‘I’m not too involved in this neighborhood. I’m not the girl who knows everyone here. I am a little distant. I know some people, who I went to school with…I am in two worlds…I am in Barbés, because I know Barbés and it is my neighborhood. And on the other hand, I am in another world—the world of those who want to succeed and leave this neighborhood.’ (Leila, Female, 20). When I detailed Le Grand Paris project to Leila, she responded: ‘[The project] is not really going to change the perceptions of people…We are going to stay in this Paris-banlieue thing...I think the discourse is going to be the same.’ (Leila, Female, 20). Leila went into more depth about her personal experiences, particularly with the schooling system in the 18éme, and feeling like she was navigating a ZEP. She described how she went to one of the few majority white high schools near her home and people would laugh whenever she spoke in class: ‘Some would call me the “girl of Goutte d’Or” “Bamboula,” “maracaille”.’ (Leila, Female, 20). Leila also explained how sometimes she would resist these labels by speaking up, but that never amounted to much: ‘Some teachers heard and didn’t’ say anything…And some teachers stigmatized me. I felt like “la petite black”.’ (Leila, Female, 20). Leila complained to school officials and they suggested placing her in a remedial school, but she refused, instead opting to redo a year of high school (Figure 4).

1. placemaking through affinity bonds;

3. navigating violence between worlds; and

4. self-esteem through leadership

After speaking with Leila, I met with Martin. Martin is 20 and of Black French Caribbean descent. Martin was born in Seine- Saint-Denis, moved to Sarcelles with his family and then at the age of 6 arrived in the 18éme. When we spoke, he was living near a police station with his parents and looking for work. I asked how he felt seeing the police so often, and he said it did not bother him too much, but it bothered his parents. He explained that the police were usually there to deter people from delinquency. Martin went on to make a Distinction between the “youth” in his area and the “residents”: ‘The ‘youth’ tend to want to appropriate an area as their own and tell residents that it is their place.’ (Martin, Male, 20). I asked Martin about his general participation in civic activities and he cited Club Barbés as his main civic activity. He explained that at the age of 14 he joined the Club because the Club was organizing a trip abroad. He said he never traveled with his parents, so the trip with the Club was exciting at the time. Following the trip, he described how the president of the Club remained invested in his academic development and so he decided to stay with the association. He almost felt like “he [owed] the club a lot.” Then, I asked Martin to explain how people reacted when he shared where he lived: ‘I say ‘I am from Barbés. You are from Barbés!’ And they are shocked because they all think we hang outside…I defend my neighborhood though! I tell them it used to be more dangerous before than it is now.’ (Martin, Male, 20). Martin added that he preferred the banlieue, parts like Creteil and Sarcelles because “there is more space...more stable.” Next, I asked Martin about Le Grand Paris, and he replied: ‘It’s hard for me to see what it is. I understand it though…it’s better...more convenient to regroup people together.’ (Martin, Male, 20) (Figure 5).

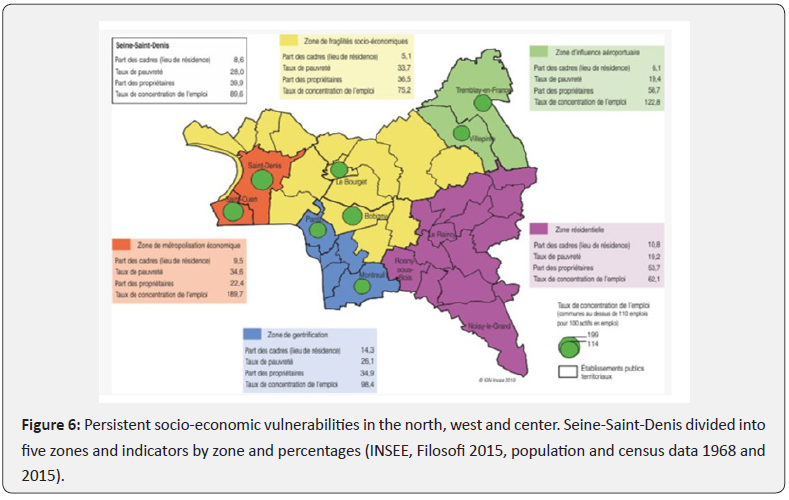

Boundary-Pushing

For the banlieusards in my study, Le Grand Paris seemed like a distant idea, but the objectives of the project appeared culturally relevant and resembled a strategy to improve the local economy. My study participants also felt that Le Grand Paris could attract more businesses (shopping centers, etc.) to Seine-Saint-Denis, which might enhance their job prospects. For the young people living in the 18éme, visualizing the impact of Le Grand Paris was harder. Perhaps, because life in Paris in the 18éme was already difficult due to financial hardships and the social environment. Also, moving out of the 18éme for some participants would require obtaining a permanent work contract with a CDI “Contrat à Durée Indéterminée,” which was often challenging to negotiate with employers. Overall, members of JEM and Club Barbés shared the same sentiment that having affinity groups helped them foster a positive outlook about the future. In Distinction [25] Bourdieu argued that symbolic violence was used to maintain boundaries over long periods of time while creating hierarchies of social and spatial identities. As a contemporary urban ethnographic study on urban renewal and its impact on life in ‘the city,’ my research challenges the idea that “boundary-pushing” only occurs at the extreme margins of society [26,27]. “Boundary-pushing,” as a social, emotional, and economic process, takes place among immigrants and nonimmigrants; employed and unemployed; the educated; young; and mobile. “Boundary-pushing” is also public, and plays out in everyday interactions— at school, shopping, in the metro. This, in turn, leads to a greater sense of personal competence, creativity, and even moral achievement for the would be “boundary-pushers [28-31] (Figure 6).”

References

- The Duflot Law.

- Feargus O’Sullivan (2013) New Rent Laws Keep Paris From Becoming Only for the Rich.Bloomberg City Lab.

- The Law of 27 January 2014 to modernise territorial public action and to assert metropolises-MAPTAM.(2014)Legislation.

- Fairclough, Norman (2001) Language and Power. Routledge.

- Teun Van Dijk(1997) Discourse as Social Interaction. Sage.

- Ruth Wodak (1997) Gender and Discourse. Sage.

- Charaudeau, Patrick (1997) The Media News Speech. The construction of the social mirror.Nathan/National Audiovisual Institute, Paris.

- Rahul Ramagundam (2005) The ‘State’ Revealed in Newspaper Headlines. Economic and Political Weekly 40(2): 100-102.

- Minichiello V, Aroni R, Timewell E, Alexander L (1995)In-depth interviewing: Principles, techniques analysis (2nd), Melbourne: Longman.

- INSEE-National Institute of Statistics and Economic studies(2020)Paris Municipal Rounding 18th Arrondissement (75118).

- INSEE-National Institute of Statistics and Studies (2020) La Seine-Saint-Denis: between economic dynamism and persistent social difficulties - Insee Analyses Ile-de-France No. 114.

- INSEE-National Institute of Statistics and Studies (2020) Territory comparison, Paris Commune 18th Arrondissement (75118).

- Fanon, Frantz (1952)Black Skin, White Masks. Grove Press,United States.

- Pap Ndiaye(2007) The Black Condition: Essay on a French Minority. Paris, Calmann-Lé Nicolas Sarkozy continues to vilify 'scum and thugs.The World.

- DominiqueDuprez (1997) Between discrimination and disaffiliation: The experience of young people from Maghreb immigration. The Annals of Urban Research. 76(1): 78-88.

- Mehta, Brinda (2010) Negotiating Arab-Muslim Identity, Contested Citizenship, and Gender Ideologies in the Parisian Housing Projects: FaïzaGuène'sKiffekiffe tomorrow. Research in African Literatures41(2): 173-202.

- Equality Act (2006) ChancesNational Council for Policies to Combat Poverty and Social Exclusion (CNLE).

- Sabbagh, Daniel (2004) Affirmative Action at Sciences Po. Race in France: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Politics of Difference. Berghahn Books.

- Castel, Robert (2006) Negative Discrimination: The citizenship deficit of suburban youth. Annals. History, Social Sciences. 61st Year, No4. Ehess.

- Nora, Pierre. Between Memory and History: The Places of Memory. Representations. University of California Press,California, United States, 7-24.

- Roberta Dessí (2008) Collective Memory, Cultural Transmission, and Investments. The American Economic Review 98(1): 534-560.

- Loïc Wacquant (2007) Territorial Stigmatization in the Age of Advanced Marginality. Thesis Eleven 91(1): 66-77.

- Colette Petronnet (1982) Inhabited space. Suburban ethnology. Galileo,Paris.

- Bronner, Luke (2011) The unanimous euphoria of the elected representatives of Seine-Saint-Denis. The World.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1979) The Distinction: social critique of judgment.Midnight Editions, Paris.

- Lamont, Molnar (2002) The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 167-195.

- Lamont, Bail (2007)Bridging Boundaries: The Equalization Strategies of Stigmatized Ethno-racial Groups Compared.CES Working Paper.

- Dossiers: The figures of the Ile-de-Franceregion (2018) The prefecture and state services in the region.

- France Diplomacy-Secularism and Religious Freedom.” French and European Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Greater Paris: a target of building 70,000 homes per year. The New Observer.The Archives of the World (1944-2020) Le Monde.

- Zagrodzki, Mathieu. What is the police doing? The role of the police officer in society. Editions Dawn