Skill Shortage in Labor Market and COVID19: Some Policy Recommendations

İbrahim ÜNALMIŞ1* and Meltem Ferendeci ÖZGÖDEK2

1Associate professor, TED University, Chair of Business Administration Department, Turkey

2Part Time Lecturer at TED University, Human Resource Management Specialist, Turkey

Submission: August 18, 2020; Published: September 15, 2020

*Corresponding author: İbrahim ÜNALMIŞ, Associate professor, TED University, Chair of Business Administration Department, Turkey

How to cite this article:İbrahim Ü, Meltem F Ö. Skill Shortage in Labor Market and COVID19: Some Policy Recommendations. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2020; 5(5): 555673. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555673

Keywords:Economies; Society; COVID19; Labor Organization; Crises; Labor market

Short Communication

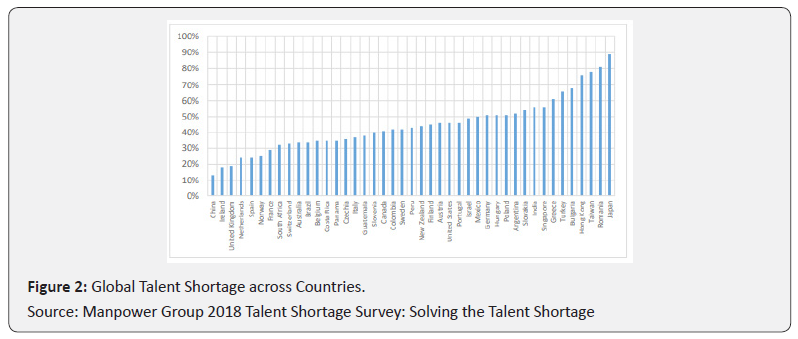

Talent shortage is defined as having lack of skills to do a work and considered as one of the most important reasons of unemployment in many countries. According to the Manpower Group’s statistics global talent shortage has increased significantly in the last decade1 (Figure 1). The main reason behind this trend is the widening gap between skills needed at work and current skill set of labor force. Specifically, we observe a rapid digitalization and automation of production processes at work. However, skill set of current labor force do not change at the same phase to adopt new environment. The unavoidable result is the evidence of skill shortages across countries (Figure 2). Interestingly, this is not only the problem of developing economies but also problem of advance economies as well. In addition, a report published by the World Economic Forum argues that one third of skills required to find a job will change in the near future2. This implies that this problem will intensify further in the near future.

FOOTNOTE

1Talent Shortage 2020, Closing the Skills GAP: What Worker Want?, Manpower Group, 2020.

2https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-10-skills-you-need-to-thrive-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/

How COVID19 will Affect Talent Shortage?

COVID19 will reshape economies and societies. We have already started to see this transformation. Evidently, we know that demand and supply shocks, as in the case of COVID19, lead to persistently higher unemployment rates in economies. Aghion et.al. (2005) shed light on the reasons behind this phenomena. They argue that firms prefer to implement structural changes in their operations during crisis times. Therefore, workers who become unemployed during crisis times cannot find a similar job in the post crisis period. In addition, some sectors grow and some sectors shrink during crisis times. This necessitates a shift from declining sectors, such as tourism during COVID19 period, to booming sectors, like online shopping. However, moving from one sector to another requires new skill sets. As Hyman and Ni (2020) show workers who lost their job during crisis times and attend training courses can find a job relatively quickly in the post crisis period3.

Unlike other crisis periods, this structural change has become faster due to COVID19 pandemic. Companies that can shift their sales to online platforms easily, that can meet hygiene requirements, that can adopt changing international supply chains, that can adopt automation and that can shift to distance work swiftly will stay competitive, hence, stay alive. On the other hand, these transitions imply significant changes in skill requirements of workers as well as sectoral shifts of work force. In a recent report, International Labor Organization (ILO) mentions that tourism, transportation, automobile sectors are on decline and health and retail sectors are booming. Therefore, we should expect a workforce shift from declining industries to booming industries. However, the question is whether former tourism and transportation employees have the relevant skills to work in health and retail industries?

FOOTNOTE

3Hyman B.G., Karen X. Ni, 2020, Job Training Mismatch and the COVID-19 Recovery: A Cautionary Note from the Gareat Recession. Liberty Street

Mass Skill Changes are Crucial for the Future of Our Societies

Considering the recent developments and our previous insight about the effects of crises on labor market we propose the following policy recommendations:

i. The problem we face with is gigantic and requires swiftEconomics, Federal Reserve Bank of New York actions.

ii. Governments, universities, non-governmental organizations and companies should set up a discussion platform to share their views and ideas.

iii. Booming sectors and required skill sets in these sectors should be identified.

iv. The number of work force that needs a new skill set should be identified.

v. Swift workforce shift possibilities across sectors without any additional training should be considered.

vi. Some sectors need “on job training” to adopt new business environment. Such trainings should be arranged without waiting the end of the COVID19 pandemic.

We argue that there is no time to waste to take such measures. If we do not care about the talent/skill shortage across countries there will be high and persistent unemployment problem in many countries. Needless to say, future of our societies depends on our current actions about labor markets.

References

- Desmetz H(1967)Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review Paper and Proceedings 57: 347-359.

- Coase R (1937) The Nature of the Firm. Economica 4(16): 386-405.

- North DC (1987) Institutions, transaction costs and economic growth. Economic Inquiry 25(3): 419-428.

- Saint-PaulG (2000)The Political Economy of Labour Market Institutions. Oxford University Press.

- AcemogluD, Johnson S, RobinsonJA(2005) Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth. Handbook of Economic Growth 1A: 386-472.

- Acemoglu D, Johnson S & Robinson JA (2005) The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, Institutional Change and Economic Growth. American Economic Review 95(3): 546-579.

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2002) Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective. NBER Working Paper no 8831.

- Acemoglu D (2006) Modelling Inefficient Institutions, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No.11940.

- AcemogluD, Robinson JA (2006) Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective American Political Science Review 100(1): 115-131.

- GlaeserEL, Shleifer A (2002)Legal origin. The Quarterly Journal of Economics117(4): 1193-1229.

- Granovetter M (1985) Economic Action and Social Structure: the problem of Embeddedness. The American Journal of Sociology 91(3): 481-510.

- GranovetterM (2005)Struttura sociale ed esiti economici. Stato e Mercato 72: 355-382.

- Putnam RD (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civil Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton University Press,New Jersey, United States.

- Fligstein N, Dauter L (2007) The Sociology of Markets. Annual Review of Sociology 33(1): 105-128.

- Sachs JD (2001) Tropical Underdevelopment. NBER Working Paper No. 8119.

- Downs A (1957) An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.Journal of political economy 65(2): 135-150.

- WittmanD (1973)Parties as Utility MaximizersAmerican Political Science Review67(2): 490-498.

- HamiltonA, JayJ&Madison J (1966) The Federalist Papers: A Collection of Essays Written in Support of the Constitution of the United States: from the Original Text of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay, Selected and Edited by Roy PFairfield, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,Maryland, United States.

- Besley T, Persson T & Sturm D (2005) Political Competition and Economic Performance: Theory and Evidence from the United States.

- Besley T, Persson T & Sturm D (2010) Political Competition, Policy and Growth: Theory and Evidence from the US. Review of Economic Studies 77(4): 1329-1352.

- PerssonT, Roland G, Tabellini G (1997)Separation of Powers and Political Accountability. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(4):1163-1202.

- Persson T, Roland G & Tabellini G (2000) Comparative Politics and Public Finance. Journal of Political Economy 108 (6): 1121-1161.

- Leonida L, Maimone DA & Navarra P (2013) Testing the Political Replacement Effect: A Panel Data Analysis, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Department of Economics, University of Oxford 75(6): 785-805.

- Leonida L, Maimone, DA, Marini A & Navarra P (2015) Political competition and economic growth: A test of two tales Economics Letters, Volume 135(C): 96-99.

- Rodden J, Rose-AckermanS (1997)Does Federalism Preserve Markets? Virginia Law Review83(7): 1521-1572.

- Drazen A (2000) The Political Business Cycle after 25 Years. NBER macroeconomics annual 15.

- FriedmanP, TaylorB(2011)Entry Barriers and Innovation in the Market for Governance. academia.edu.

- Persson T, Tabellini G (1994) Is Inequality Harmful for Growth? American Economic Review 84(3): 600-621.

- Persson T, Tabellini G (2001) Political Institutions and Policy Outcomes. What are the Stylized Facts?

- Weingast BR (1993) Constitutions as Governance Structures: The Political Foundations of Secure Markets. J.Institutional & Theoretical Econ: 286, 287.

- Weingast BR (1995)The Economic Role of Political Institutions. Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development J.L. Econ. & Org.

- Skilling D, Zeckhauser RJ (2002) Political Competition and Debt Trajectories in Japan and the OECD. Japan and the World Economy 14(2): 121-135.

- DixitA, Londregan J (1995) Redistributive Politics and Economic Efficiency. American Political Science Review 89(4): 856-866.

- Fernandez R, Rodrik D (1991) Resistance to Reform: Status Quo Bias and the Presence of Individual Specific Uncertainty. American Economic Review 81(5): 1146-1155.

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2012)Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. Profile Books Ltd,London, United Kingdom.

- Desmetz H(1967)Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review Paper and Proceedings 57: 347-359.

- Dolfin M, Knopoff D, LeonidaL& MaimoneD(2017) Escaping the Trap of Blocking’: A Kinetic Model Linking Economic Development and Political Competition. Kinetic and Related Models 10 (2): 423-443.