Models of Understanding the Suicidal Phenomenon are Key to the Design of Prevention Programs in the 21st Century

Telva Carceller Meseguer1,2 and Ana Isabel De Santiago Díaz1,2*

1 Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Spain

2Instituto de Investigación Valdecilla, Spain

Submission: May 15, 2020; Published: May 28, 2020

*Corresponding author: Ana Isabel De Santiago Díaz, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla and Instituto de Investigación Valdecilla, IDIVAL, Santander, Spain

How to cite this article:Carceller-Meseguer T, De Santiago-Díaz AI. Models of Understanding the Suicidal Phenomenon are Key to the Design of Prevention Programs in the 21st Century. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2020; 5(3): 555662. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555662

Abstract

Conception of suicide have changed throughout the history of mankind. Since magical-religious ideas were abandoned from the 19th century onwards, the concept of suicide has radically changed and made way for science and sociology. Theories and evidence have been provided throughout the 20th century, which reveal that the psychopathological and social determinants of suicide are essential for the comprehension of this complex phenomenon. Currently, the different models of understanding can be integrated into a multidimensional framework that allows for the explanation of suicidal behaviour, with the main goal of designing suicide prevention strategies.

Keywords:Suicide; Suicide behaviour; Psychopathology; Sociology; Prevention

Introduction

The conceptualization of suicidal behavior has changed throughout human history. We know that suicidal behavior is a very old human phenomenon, which has been receiving diverse meanings through the different stages of history and cultures, being approached consequently according to the conception and the meaning given to it. The knowledge and study of the phenomena relevant to science and to the human being usually follow oscillating courses in their theorizations and their interpretations. We usually find in its development an articulation of polarized positions that finally converge in more global and integrating conceptualization models. In the case of suicidal behavior, since magical-religious ideas were abandoned in the 19th century, the concept of suicide has radically changed and made way to science and sociology [1]. In the second half of the 19th century, it was in France that the concept of suicide acquired the fundamental feature that still characterizes it today: a psychopathological fact conditioned by social circumstances. From the French alienism, represented by Esquirol, considers suicide as a psychopathological phenomenon, in which predisposition played a determining role [2]. Simultaneously from the Sociology, Émil Durkheim raises the hypothesis of the social determination for suicide resulting from anomie (disintegration and lack of sense of belongingness of the individual in social groups of reference) [3]. Throughout the 20th century, theories and evidence have been provided which reveal that both psychopathological and social determinants are essential to the understanding of this phenomenon.

Without a doubt, one of the great challenges that began in the 20th century and that have become more relevant in the 21st century has been the approach and prevention of suicidal behaviour. We know that the therapeutic approach to any health problem in general, particularly in suicidal behavior, requires the adequate description, definition, and global conceptualization of the phenomenon. This conceptualization must include, if possible, comprehensive explanatory and predictive models.

Discussion

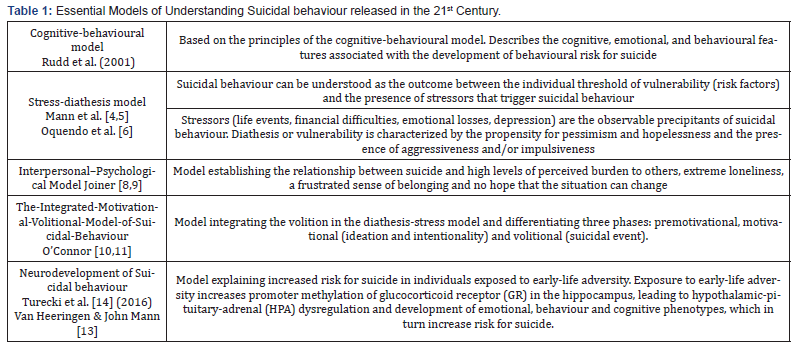

At 1999 John Mann and his colleagues propose a stress-diathesis model in which the risk for suicidal acts is determined not just by a psychiatric illness (the stressor) but also by a diathesis. This diathesis may be reflected in tendencies to experience more suicidal ideation and to be more impulsive and, therefore, more likely to act on suicidal feelings [4]. This clinical model of stress-diathesis represents an enormous advance in the understanding and explanation of the phenomenon, focusing on the importance of the interaction of life stressful events on a basis of personal vulnerability. In this model, stressors are observable precipitants for suicidal acts, including depressive episodes or life events such as financial difficulties or disruption of a relationship. The diathesis is characterized by a tendency toward pessimism and a propensity for aggression/impulsivity [5]. This model was described on the basis of retrospective studies, being proved later in prospective studies [6]. The cognitive, emotional and behavioural features associated with the development of behavioural risk for suicide [7] and the interpersonal variables play a determining role too in this complex interaction of factors in the stress-diathesis models [8]. High levels of loneliness, a frustrated sense of belongingness and the perception of being a burden on others can be very important risk factors to consider, in addition to personal risk factors and life events or stressors [9]. At the beginning of the second decade of our century, in the framework of the motivational theory, a new contribution to understanding suicidal behaviour appears: integrated motivational-volitive model [10]. Although suicidal behavior is presented to us as an event of abrupt appearance, the truth is that it constitutes the end point of a long emotional trajectory that this model is able to categorize into three phases: pre-motivational, motivational (the suicidal ideation and intentionality) and volitional (suicidal act) [11]. This model allows a vision of suicidal behavior in the chronological axis of life, where non-observable and observable suicidal behavior become both relevant and need to be approached. Finally, we use a model that connects all the variables that have been seen more or less independently, in a bio-psycho-social model, which establishes changes in neurodevelopment caused by early stressful events, with evidence obtained from studies using diverse designs, postmortem and in-vivo techniques [12,13]. A series of changes occur in neurodevelopment, as a consequence of exposure to adversity in the first years of life: increased methylation in the hippocampus, which causes deregulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, conditioning the development of emotional (instability), behavioral (impulsivity) and cognitive (difficulty in attention, decision making and problem solving) phenotypes that increase the risk of suicide [14]. Table 1 shows a summary of the explicative models of the suicidal behavior we have just described.

The different contributions that have been added to the concept of suicide, developed at the end of the 19th century as a socially and psychopathological determined phenomenon, have been numerous and have established the current conceptualization of suicide as a broad and complex phenomenon. Suicide is the result of the synergy of genetic, psychological, social, and cultural factors, overlapping with experiences associated with trauma or loss.

Conclusion

It is essential for the design of suicide prevention programs to have a model to understand, explain and predict suicide. Currently, the contributions of successive models of understanding the suicidal phenomenon can be integrated into a multidimensional framework that also requires a multidisciplinary approach addressing bio-psycho-social factors. This allows a more global approach to the comprehension of suicidal behaviour and facilitates the design of therapeutic targets and suicide prevention strategies.

References

- Daray FM, Grendas L, Rebok F (2016) Changes in the conceptualization of suicidal behavior throughout history: from antiquity to the DSM-5. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba 73(3): 205-211.

- Esquirol JE (1838) Des maladies mentales. In: JB Tircher (Ed.), Beuxelles.

- Durkheim E (1897) Le suicide. In: F Alcan (Ed.), Paris.

- Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM (1999) Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 156(2): 181-189.

- Mann JJ (2002) A current perspective of suicide and attempted suicide. Ann Intern Med 136(4): 302-311.

- Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, et al. (2004) Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 161(8): 1433-1441.

- David RM, Thomas J, Rajab MH (2001) Treating Suicidal Behavior: An Effective, Time-Limited Approach. New York, Guilford Press, USA.

- Joiner T (2005) Why People Die By Suicide. Boston: Harvard University Press, USA.

- Joiner TE, Van Orden KA (2008) The interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior indicates specific and crucial psychotherapeutic targets. Int J Cogn Ther 1(1): 80-89.

- O’Connor RC (2011) The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis 32(6): 295-298.

- O’Connor RC, Nock MK (2014) The psychology of suicidal behaviour. The Lancet Psychiatry 1(1): 73-85.

- McGirr A, Diaconu G, Berlim MT, Pruessner JC, Sablé R, et al (2010) Dysregulation of the sympathetic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and executive function in individuals at risk for suicide. J Psychiatry Neurosci 35(6): 399-408.

- Van Heeringen K, Mann JJ (2014) The neurobiology of suicide. The Lancet Psychiatry 1(1): 63-72.

- Turecki G, Ernst C, Jollant F, Labonté B, Mechawar N (2012) The neurodevelopmental origins of suicidal behavior. Trends Neurosci 35(1): 14-23.