Student Motivations that Predict the Self-Selection and Choice of Blended Instructional Delivery

Michael Seredycz*

Department of Sociology, MacEwan University, Canada

Submission: May 08, 2020;; Published: May 19, 2020

*Corresponding author: Michael Seredycz, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, MacEwan University, 10700 104th Avenue Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

How to cite this article:Michael S.Student Motivations that Predict the Self-Selection and Choice of Blended Instructional DeliveryAnn Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2020; 5(2): 555659. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555659

Abstract

This case study examined 303 undergraduate students enrolled in seven traditional face to face courses who were offered the opportunity to self-select into one of four blended modes of instruction. Students could select face to face (F2F) intervals of 90% (almost exclusively in the classroom) to 70%, 30% and 10% (almost exclusively online with the exception of final exams). Findings suggest that students preferred a blended 70:30 face to face instructional delivery. Motivating factors including but not limited to the age of the learner, employment, flexibility and convenience, the number of courses a student is enrolled in, whether a course was an elective for their degree completion and commuting distance were all found to be significant factors in predicting a student’s self-selection of instructional delivery.

Keywords: Online; Blended; Hybrid; Instructional delivery; Face to face; F2F; Self-selection; Grade attainment

Introduction

The COVID19 coronavirus led the World Health Organization (WHO) to identify a global pandemic in 2020 which forced the closure of thousands of schools, colleges and universities across the United States and abroad [1]. As the WHO reports, this is the first time in recorded history where “technology and social media are being used on a massive scale to keep people safe, productive and connected while being physically apart” [1]. This has led colleges and universities across the world to scramble to attempt to complete courses online without face to face community spread in the classroom. This global pandemic [1] has forced instructors to adopt radical approaches to complete their courses online potentially neglecting their own unique outcomes but rethinking how their courses can be implemented in the future. This article offers a glimpse into how self-selection of instructional delivery could assist in delivering courses in the future.

Academic learning within post-secondary institutions has traditionally been face to face (F2F) teaching instruction. The scholarship of teaching and learning has always encouraged and promoted the use of best practices determining what works, what doesn’t and what is promising [2-6]. However, there is no one size fits all, universal method of instruction simply because each instructor is unique in their own delivery [7-9]. Every instructor has their own unique outcomes for their coursework (Singh, 2006) and this certainly varies based on class size [10], lecture versus seminar courses [11-13], basic versus applied courses [11,14] and by discipline [15].

As such, governments, post-secondary institutions and students/ consumers have begun pondering whether online programming is more effective than blended or face to face engagement in the classroom. As such, the timing of this study may not be more appropriate. How do universities and faculty react to a changing online environment and how might students wish to proceed in an online/hybrid environment? What are student motivations for taking blended coursework and furthermore, what might be the most appropriate level of engagement that ensures strong performance outcomes? This case study focuses on approximately three hundred students within seven undergraduate courses at a medium sized liberal arts midwest American university.

Literature Review

Research indicates that online and blended courses are reliable and valid methods of course delivery [3,5,16,17]. Similar to face to face course instruction, the evidence of the efficacy of online courses is mixed. For each study that suggests online instruction is similar or as effective as traditional classroom instruction [2], there are also studies to the contrary [18]. The reasoning is simplistic. There is a plethora of course deliveries available for instructors from the extremities of traditional F2F instruction to no F2F interaction at all.

A meta-analysis by Zhao & Breslow [19] reported that evidence is mixed in terms of the efficacy of blended versus traditional and online learning deliverables. The lack of comparison groups, low sample sizes and the differentiation of modes of delivery [19-21] impacted the efficacy of the 45 studies examined. The meta-analysis concludes that students who enroll in hybrid learning “performed modestly better” than those enrolled in F2F interactions [21]. However, there is very little research to suggest how student self-selection can impact their chosen instructional delivery. Often instructional delivery is forced on students and they do not have the opportunity to select what might be in their best interests. The purpose of this study is to build on what we know, what we don’t know and what is promising highlighting selfselection within differing/varying intervals of F2F interactions

The Sloan Consortium has adopted a scaled form of online learning delivery based on the percentage of content delivered online [2]. The lowest level of content delivered to students is denoted as web supported delivery; where online instruction is less than 30% online and focuses specifically on online content and internet sourced works. This could range from using selected readings that are available online or within a digital library consortium to the adoption of online readings developed by book publishers. Alternatively, the higher extremes of 80% and above are categorized as online. This categorization could be the implementation of entire textbooks and performance measurement outcomes. Hybrid or blended learning is determined to be within the mid-range of 30%-70%. This is where there is an inclusion of more digital content with an emphasis on some F2F lecture or seminar time (without it being diminished almost entirely).

The motivations for students selecting online and/or blended programs are based primarily on three priorities: convenience, flexibility in programming and managing their educational attainment with their employment [22]. Jaggers [23] reported that 80% of participants who selected online courses in Virginia did so due to time conflicts with employment (50% being full time employment). While many studies point to the need of flexibility of employment [23-25] when selecting courses, very few include volunteerism and/or internships. Often students will be supplementing their educational attainment with volunteer experience and/or internships that also affect their time management and flexibility, yet it is not studied with much rigor. However, there is also the possibility that other demographic variables and motivators may be able to predict why students select online or blended learning environments.

With a sample of nearly 650 undergraduate students, Harris & Martin (2012) reported that students who were older were more likely to enroll in a fully or mostly online course, while those within the 18-22 range are more likely to remain traditional classrooms, likely due to being on-campus already (being part or full time). Older students have been found to be more likely to engage with online materials [26,27], enroll in online courses [28] while also exploring and identifying new content [29]. Chyung [27] found that non-traditional and older students were more active on discussion boards than their younger counterparts, while also boasting more content-based narratives. Studies have also suggested that the older the student, the more likely they consciously examine material leading to better performance [27,30].

There is also a likely correlation that those students who are older are more likely to be employed, have a significant other, dependents and/or employed and less likely to be on campus [22,31,32]. Jaggers [23] reported that 30% of participants who selected online courses in Virginia did so due to child care time conflicts. Therefore, we should not assume that age is the strongest predictor, but rather a significant predictor of determining whether a student considers a traditional, blended or solely online course.

Boysen et al. [33] have reported that nearly half of students can feel victimized by instructor bias, either implicit or explicit. As such, instructor bias can be reduced if course delivery is managed in an online environment rather than face to face. Those who self-identify as visible minorities (whether through sex, gender, race, ethnicity) or who may have language barriers may feel more comfortable taking courses outside the classroom, where there is less likelihood of bias. Ruling out ignorance, prejudice or racism certainly should not be underestimated (via either implicit or explicit bias). The availability of an online course or more blended coursework mitigates this potential bias [34,35]. Conaway and Bethune have reported that White instructors had shown an implicit bias towards African American names more so than instructors of other ethnicities. Therefore, those students who may self-identify of a different sex, gender, race, ethnicity and/or even speak a less prevalent language than English could be more vulnerable to bias. However, as Jagger [23] suggests, those speaking foreign languages may not be as proficient in online environments that are generally in English. Perhaps, a universal design offering easy language translation could reduce these issues (which are already available online). However, it is often difficult to ascertain how prevalent demographic variables are in determining self-selection because it is likely due to unobservable factors which are likely situational and can change based on individual student circumstances.

As Xu & Jaggers [36] suggest it would be useful to compare representative online courses to traditional face to face courses. Xu & Jaggers [37] examined 24,000 students across 23 community colleges in Virginia concluding that students performed “significantly worse in online courses in terms of both course persistence and end of-course grades” (2011:375). This is further corroborated after they examined 34 colleges in Washington State, Xu & Jaggers [36] report that an online format had a significant negative impact on a student’s course persistence and grade attainment (2013: 54). This study hopes to build on their work to control for those motivating factors including influences on a students’ course selection of instructional delivery, employment, volunteerism and educational motivation like one’s field of study and grade expectations/ attainment. Furthermore, this study further accentuates the need to account for “unobservable underlying student self-selection [which] may underestimate any negative [… or positive] impacts of the online format on student course performance” [36].

Methodology

The participants of this study were chosen from seven traditional undergraduate courses offered within a midwestern American liberal arts university. Three hundred and twenty-two undergraduate students, initially unaware of any instructional self-selection study. enrolled in a typical sixty student maximum face to face 200-level required course in criminology/ criminal justice.

The study sample began with 334 eligible students enrolled in seven criminology courses during both fall and spring semesters. Twenty-two students were removed from the study having dropped or withdrawing from the course throughout the semester. An additional nine students were removed from the study for not having completed the pre-test (n=5) and/or post-test (n=4) survey. Therefore, the sample size for the purpose of analysis was 303 participants.

Each of the seven undergraduate criminology courses were offered over a sixteen-week semester cycle encompassing 34 one-hour blocks of class time. The course was designed with the specific purpose of exploring the nature of crime and theories associated with offending. The course was predicated on utilizing a text that could be offered in both print and online versions. Microsoft power point modules were also used to ensure that additional resources were included in the course to ensure the retention of key concepts, inter-connectivity with the text and any outside resources. Students would be expected to read the required text for the course in addition to supplemental technical reports, peer reviewed articles and online audio-visual clips.

Each course was designed to ensure consistency across performance measurements. Performance measures included three examinations (75% of a final grade) and three assignments worth 10%, 5% and 10% respectfully. The three examinations were proctored in class and were similar in questions and rigor. Examinations were designed for reading comprehension, retention and application of information. Three assignments could easily be related to course materials presented in class and a student’s ability to identify other valid online sources (technical reports and peer reviewed studies) to ensure connectivity and engagement to the text and course content. Assignments were designed with more emphasis on critical thinking and problem solving (associated within experiential and student-centered pedagogical approaches). Rubrics were clearly conceptualized and operationalized within an online environment with drop-box delivery systems.

Ensuring systematic and consistent performance measures were integral to ensure transparency, fairness and equity in grading for all students in these courses. Transparency in grading rubrics and performance measurement objectives would also assist students in their initial choice of selecting instructional delivery; further ensuring that blended or online delivery would be no more or less difficult.

Maintaining systematic and consistent measurements across all seven classes ensured that there would be fewer disparities in how the classes were taught. The study also attempted to alleviate concerns that online courses would require more time to grade engagement measurements. Therefore, no additional instructional time was allocated to an online delivery system that would not be present in a traditional course delivery. While significant time and energy was devoted into developing these instructional methods of delivery, no one group was asked to do more rigorous work than another group. This simplistic approach was adopted to demonstrate that instructors may not need to compromise outcomes when developing new types of instructional delivery that students could select. However, due to the simplicity of the study, there were some obvious limitations. Attendance and participation/ engagement would not be a measurable outcome. Therefore, whether in face to face classes or online, some common engagement techniques were not utilized. Students were offered discussion boards, discussion threads and online video conferencing as levels of peer engagement similar to that of a traditional classroom setting. However. these modes of engagement would not be used as performance measurements. This conflicts with other studies such as Garrison & Anderson [39] that argue engagement is important within online settings. How to cite this article: Michael S.Student Motivations that Predict the Self-Selection and Choice of Blended Instructional DeliveryAnn Soc Sci Manage 0034 Stud. 2020; 5(2): 555659. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555659 Annals of Social Sciences & Management studies Despite the lack of graded engagement, the use of office hours and/ or email for instructor feedback or assistance was still available. This study assumed that offering more immediate instructor feedback (Acton et al. 2005; Hill et al. 2013) was more important than grading engagement as a performance measure.

On the first day of classes, students were asked to choose or self-select into one of four types of instructional delivery methods. This study conceptualized and operationalized four instructional delivery systems as developed by Twigg [40] and the Sloan Consortium [2] into different categories of hybrid/blended instructional delivery: replacement (90:% F2F : 10% Online), supplemental (70% F2F : 30% Online) and two emporium options - 30% F2F : 70% Online and 10% Online : 90% F2F.

In selecting an instructional delivery mode, students were offered four options. Utilizing a replacement model approach, Twigg [40] articulates that some in class time can be replaced rather than supplemented with online or interactive learning activities. Using this model, 90% of the course would be delivered face to face and 10% online. Within this 90:10 option, 10% of course materials and assignment functions would be online with students able to interact with one another in class or through discussion boards. Over a sixteen-week semester with 34 instructional hours, 28 hours would be devoted to face to face lectures, 3 hours devoted to 3 examinations and 3 hours devoted to online learning. These three online classes would be used to replace time in class devoted to written assignments so that students could utilize reliable and valid sources of information to supplement their written work. These classes were designed around both experiential and student-centered learning strategies while also ensuring compliance in reading comprehension and retention of key concepts and themes (Chen et al. 2010; Stelzer et al. 2010).

The second option, designated as a 70:30 blended option, offered students 70% of the course within the classroom and 30% within an online environment. Within this 70:30 supplemental approach (inclusive of 34 instructional hours), 21 hours would be devoted for face to face lectures, 10 hours initially designated as face to face lectures would be substituted by 8 video-based lectures and 2 hours of independent online readings. Three hours were devoted to in class examinations. The 10 digital lecture recordings would be made available through Camtasia software within an online environment. Digital recordings of all instructor criminology/ criminal justice lectures allowed for its simple reintroduction at different intervals without revising content and/ or translation. Therefore, class-based discussions could still be utilized and implemented within an online environment.

Students could select a third option, denoted 30:70, where 30% of the course would be delivered face to face and a larger majority (70%) would be offered within an online delivery environment. The emporium approach [40] offers students a replacement of face to face discussions with more online deliverables including more Camtasia lectures and collaborative peer discussions, if students want to remain engaged. This approach offered students more independence and flexibility outside the classroom. In terms of instructional delivery, 3 hours were devoted to in class examinations, 10 hours were allocated to instructional face to face lectures with 21 hours of original lecture time replaced with 19 hours of digital Camtasia lectures and 2 hours of independent readings.

To offer students even more selection, students were offered the choice of a 10:90 instructional delivery. Similar to a very traditional online delivery, 10% of the course would be delivered face to face and 90% of the course would be instructed within an online environment. This emporium model approach offered students the most discretion and flexibility in their schedule where 3 instructional hours were devoted to examinations, 3 hours for face to face discussions that were pertinent more to assignments and examinations whereas 28 hours of instruction was delivered online. Digital Camtasia lectures and tutorials were utilized to replace all face to face lectures while discussion boards and threads were also utilized as forms of engagement (but were not graded).

Symbolic of Twigg’s [40] modelling, there inherent design of the course was to ensure that students were able to self-select and choose their instructional delivery. As such, the study wanted to ensure that students were generally satisfied with their selection. Therefore, after the completion of the first exam (one month; 8 classes into the course), students could re-select an option that they initially had not chosen. This offered each student more flexibility if they felt the instructional mode they first selected was incorrect. This buffet style approach [40] offered students the ultimate level of discretion of their own learning environment without revising any performance measures. This was also a component of the study to ascertain whether students would revise their original desired instructional method to something more useful for that individual student.

In addition to selecting an instructional delivery model, students were asked to complete a pre-test survey to attain baseline data. A pre-test self-administered questionnaire was explained in class and students were expected to complete the questionnaire and their self-selection of class instruction within two days. The questionnaire included demographic variables associated with age, sex, self-identified race and ethnicity, language preference and motivating factors which were explained previously in the literature review. This pre-test questionnaire was supplemented with validated measurements (attaining additional consent for use of a student number) to ascertain each student’s educational status (based on number of credits attained), a validated grade point average, number of courses the student was enrolled in at the beginning of the semester and their home address to determine their proximity to the University campus.

Findings

As explained previously, the study sample began with 334 eligible students enrolled in seven 200-level criminology/ criminal justice courses within a liberal arts University in the Midwest United States. Thirty-one students were removed from the study for (i) having dropped or withdrawing from the course or not completing their self-administered surveys. Therefore, 303 students were used for the analysis of this study.

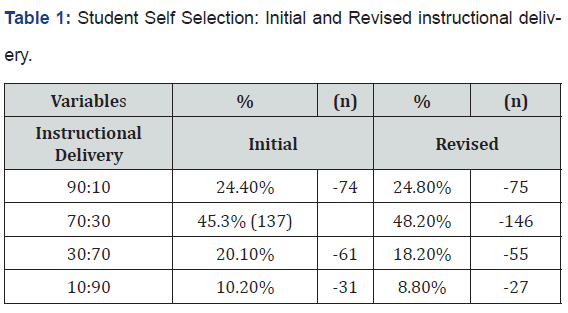

Table 1 below illustrates the self-selection of instructional delivery that each student has chosen. As explained previously, students initially chose their preferred instructional mode within the first few days of the beginning of the course. However, each student was also able to revise this choice at any time between the beginning of the course and the first examination (one month later).

When given the opportunity, a large majority of students initially selected an emporium approach (as explained by Twigg [40]). Nearly half of the seven classes of students (45%) preferred the 70:30 blended option; giving them more flexibility than the 90:10 traditional course (24%) or the more online 30:70 blended (20%) option. One in every ten students selected the almost entirely constructed course where 90% would be instructed online. However, the decisions of students became clear after one month of the course had been completed. Of those 31 students who initially chose the 90:10 option, four students re-selected to the 70:30 option. Of those selecting the 30:70 instructional delivery (61 students), six students revised their decision with one student returning to the most traditional instructional method and five moving to a 70:30 mode of delivery. It was clear that students did appreciate more of an emporium approach (64%) to traditional (25%) or almost solely online (9%) instructional delivery. The ten students who re-selected and/or revised their initial decision all had said in some form that they wanted more opportunities to interact with other students and/or attain more detail in understanding key concepts and themes. It should be noted that the revised selection options were used for further analysis.

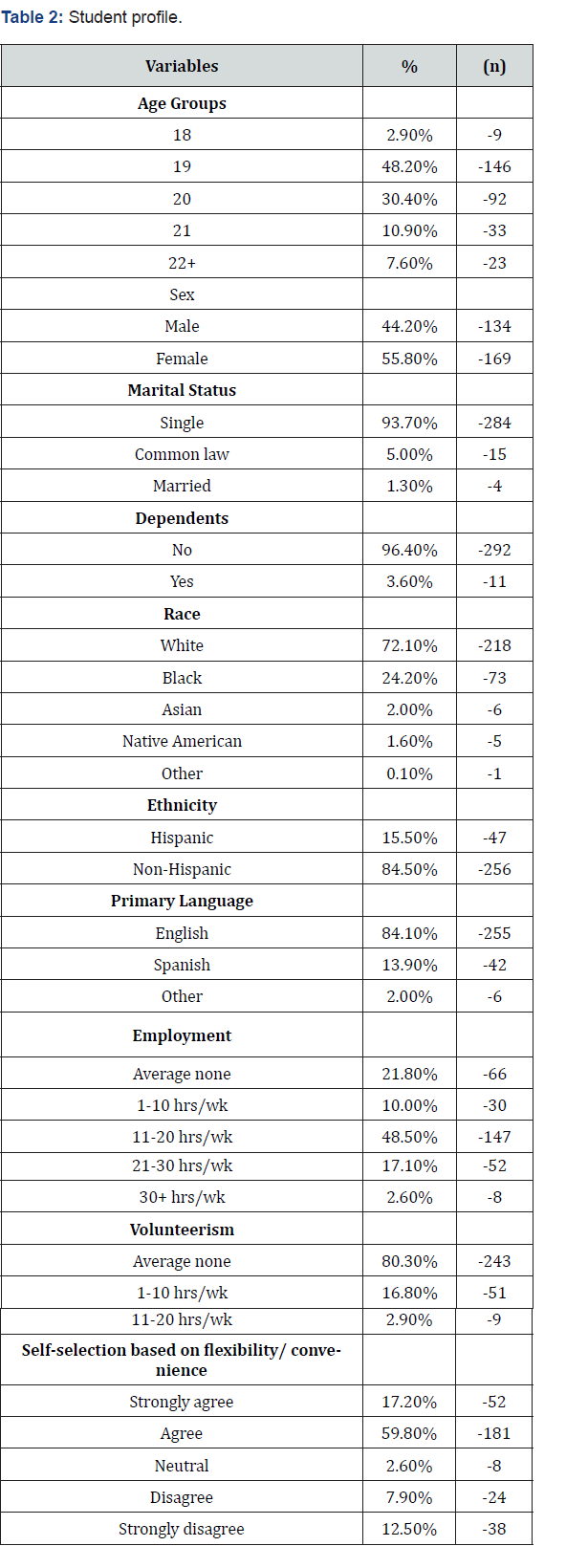

In addition to choosing their desired instructional delivery medium, students were asked to complete a short open-ended self-administered questionnaire at the beginning of the course. Responses were relevant to establishing a baseline of data points to understand the profile of the sample. Responses of the variables of interest were coded to generate the appropriate values; as seen below in Table 2.

The profile of the students studied would suggest this is a typical, traditional 200-level undergraduate course where a majority of students are young and progressing to determine their career trajectory. In terms of age, a significant majority (92%) of students who participated in the study were generally 21 or under, Similar to the University demographics, women represented a larger percentage (55%) of the students enrolled in the courses. Students represented in the sample are young, single (94%) and are without children or dependents (96%). Similar to the University’s student body demographics, the majority of students self-identified as White (72%), a large concentration of students self-identified as Black and/or African American (24%). Furthermore, those who identified as Hispanic were approximately 16% of the sample and typical of the student body at the University where this study was conducted. English was the primary language spoken and was not a limitation to this study as all students had a proficiency in English despite 16% of respondents suggesting English was their second language.

The open ended pre-test also encouraged students to explain some of their current and/or situational factors that may be impacting their self-selection of instructional delivery. As denoted within the scholarship of teaching and learning research, students are often employed and/or volunteering outside of the classroom to supplement their career aspirations. Almost eight in ten students in courses reported being employed at the time of being enrolled in the course. A large majority of students (58%) reported working part time while as many as 19% of the students reported working over 20 hours a week in addition to their coursework. A large percentage of students (80%) were not involved with volunteerism and/or internships at the beginning of the course. This is likely due to their workload in and out of the classroom. A further question asked students to report whether time flexibility and/or convenience would impact their decision to self-select into a specific instructional method. Three-quarters of students reported that they agreed (60%) or strongly agreed (17%) that flexibility and convenience would have an impact on their decision. These findings would substantiate the literature as to why students may consider blended or online learning.

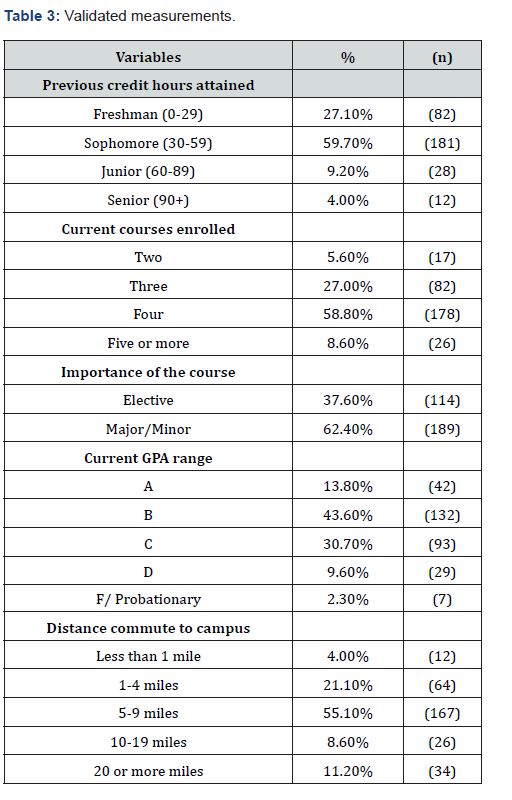

In addition to the self–reporting of the students, it was also important to attain other validated measurements. Student consent to the study allowed for the use of their University student number to access other variables of interest (Table 3).

Validated measurements of students were able to supplement the knowledge attained by students while also ensuring more validated measurements focusing on accuracy. As such, it appears that these measurements validated the data that was self-reported by undergraduate students in the study. Consistent with the previous table, the ages of students and credits attained matched to substantiate that students enrolled in the 200-level criminology/ criminal justice courses were typically freshmen (27%) and/or sophomores (60%), thereby not having significant progress towards their degree. This would explain why a low percentage of students may not be as active in volunteerism and/ or internships (as they are still deciding on their career path).

Furthermore, a large majority of students were taking larger numbers of classes simultaneously. Less than 6% of the students were taking courses on a part time basis while a remarkable 94% of students were taking three or more classes (considered full time employment). This is particularly troubling as nearly 8% of the sample were taking the most courses allowed (without permission) at five courses within the same semester. If we consider that nearly 60% of students are also employed part time and another 20% of students are working over 20 hours a week, this could be considerable strain on many students within the sample.

The relative importance of the course was another variable of interest that is often not considered particularly pertinent in the literature. Perhaps students who are more likely to engage in a their designated career path (in this case criminology/ criminal justice) feel that face to face course work might be more ideal versus students who perceive the class as simply an elective (and/ or perhaps a class they simply have to complete their liberal arts degree). A majority (62%) of the students enrolled in the seven courses were utilizing the class as a chosen major or minor of their study while 38% of students were taking the class as an elective and/or general course (not having declared a major or minor in criminology/ criminal justice).

Two variables of interest that are often self-reported and not necessarily validated in the literature were two of the final variables of interest. Preferring precision and accuracy, University Registrar records report that a large percentage of students (74%) were in the grade point average (GPA) range of a B to C. A lesser number of students had an A average (14%) while one in ten students (11%) were considered more high risk (having attained a D, F and/or probationary score). The second variable of interest was meant to assess and test the effect of commuting distance to determine if a longer commute to campus had an impact on self-selection. The University is considered more a of a commuter campus and as such, the student data was supportive of this analogy. Three of four students lived further than 5 miles from campus making the commute particularly more time consuming. This study did not address parking or public transportation. However, it appears that a substantial percentage of students would require time to commute as nearly one in five students commute over 10 miles each way, as per their schedule (which is predominantly two to three times a week) which could be five days a week. It would be expected that the longer the commute, the more likely students may select a more online based course. However, as illustrated above, a majority of students are taking a full-time course load so they may likely need to commute to campus for other courses. This should be considered when considering self-selection.

The following section examines how self-reported and further validated motivating factors predicted a student’s self-selection of blended or hybrid instructional delivery. Due to a lack of variation in responses, several variables were unable to be included in the multivariate analysis. This includes one of the dependent variables (the 90% face to face to 10% online instructional delivery). For this reason, these variables were excluded to ensure a reduced level of error and multicollinearity. With a sample size of 303 students, the data analyses attempted to control error and multicollinearity with a tolerance level of 2 and a variance inflation factor of 4.0 to ensure that data outliers would be removed from the analysis.

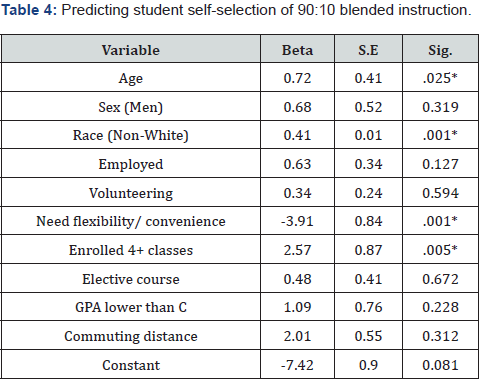

Table 4 below examines the predictive power of motivating factors that influence students’ self-selection of rhe most traditional form of instructional delivery where 90% of the course is face to face with 10% of the course within an online environment. This model was found to be statistically significant (.001 with a confidence level of 95% with the p < .05 being significantly different than zero). The motivating factors within the model explained 36% of students selecting a 90:10 more traditional instructional delivery (versus other delivery methods) based on a Nagelkerke R Square. The regression reported a Chisquare of 184.32 and a model -2 Log likelihood of 243.49 (with 10 degrees of freedom).

Findings suggest that while the model was good at predicting a 90:10 delivery of course instruction, only four variables were statistically significant at the .05 level. Those who were older were more likely to take a traditional face to face instructional method than a more blended or online approach. This is an interesting finding as you would expect that the older a student is, the more responsibilities they may have outside of taking courses at the university. However, the limitation of the study is that the range of the students who took this course was from 18 to 37. As such, it may not be representative of students in their mid to late 20s as a large percentage of students were below the median of 20. Students who self-reported as non-White were more likely to take a 90:10 delivery method than students who were White. While race has been considered a variable of interest, it may be difficult to determine why this could be the case in this model.

The two most significant variables in the analysis (based on the Beta values) were those who did not require flexibility/ convenience and students who were enrolled in four or more classes within the same semester. It appears that students who did not require additional flexibility in their schedules were more likely to take a 90:10 deliverable course. This is consistent with some of the research that has been conducted. Furthermore, students who were enrolled in four or more courses within that particular semester (equating to 12 credit hours or more) were more likely to consider a more face to face instructional delivery. While this appears to contradict the idea of flexibility and convenience, this finding could be a result of students having to attend other classes on campus and therefore, simply chose to attend class because they were on campus already. This finding would require further research to substantiate.

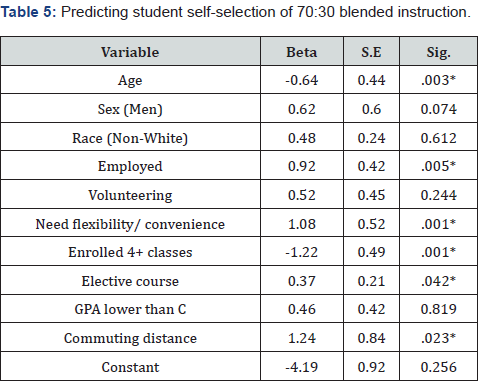

The Table below examines the strength of ten motivating factors influencing students’ self-selection of the most prevalent 70:30 instructional delivery. In this mode of instructional delivery, 70% of the course is face to face and 30% of the course is available within an online environment. This model was also found to be statistically significant (.001 with a confidence level of 95% with the p < .05 being significantly different than zero). The motivating factors within the model explained 51% of students selecting a 70:30 instructional delivery based on a Nagelkerke R Square. The regression reported a Chi-square of 244.81 and a model -2 Log likelihood of 314.26 (with 10 degrees of freedom). It should also be noted that three cases/outliers were removed from the analysis to ensure there was no multicollinearity.

The model explained in Table 5 finds that half of the variables of interest are significant when understanding a blended form of instructional delivery (versus other modes of delivery). Findings suggest that there is considerable differentiation as to why students in this sample chose blended learning versus a traditional form of instructional delivery (Table 4). Age remained a significant demographic variable of significance. It appears that the younger the student, the more likely they would enroll in a 70:30 blended instructional delivery of a criminology class. This could be due to a number of other corresponding factors such as comfortability of online environments or different priorities (versus older students). More study would be needed.

Employment, or the more a student works per week was found to be significant in determining if a student selected a 70:30 blended instruction. It also appears that other factors or a complex set of factors is having the most impact on a student’s selection of 70:30 delivery.

The Beta values above would suggest that the three most significant motivating factors was the commuting distance of students, enrollment of fewer than four courses per semester and the need for flexibility/ convenience in their scheduling. These variables of interest have all been found to be significant in other research studies. In this particular study, it would appear that the longer the commute a student has to the University (from their primary listed address), the more likely they would consider enrolling in a 70:30 blended instruction. This would also correspond to the relevance of taking fewer classes and perhaps not being on campus as often, providing them more flexibility and convenience. As we know, most students will select courses on particular days (Monday, Wednesday, Friday or Tuesday, Thursday) rather than five days a week. It also becomes apparent that students who take the course as an elective were more likely to consider the 70:30 blended instruction than those students who enrolled in the course to fulfill their major or minor liberal arts degree requirements. Therefore, with a commuting distance, higher levels of employment per week and convenience, it would not be self-serving if students selected a traditional method especially considering that they are taking fewer classes.

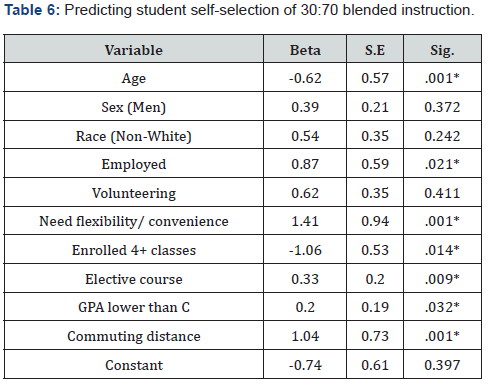

Table 6 illustrates the predictive power of ten motivating factors that influence a student’s selection of a 30:70 blended instructional offering (versus other instructional deliveries). The model was found to be statistically significant at a .001 with a confidence level of 95% (with the probability < .05 being significantly different than zero). The variables of interest within the model explained 52% of students selecting a 30:70 instructional delivery based on a Nagelkerke R Square. The regression reported a Chi-square of 219.65 and a model -2 Log likelihood of 307.24 (with 10 degrees of freedom). It should also be noted that the same three cases/outliers were removed from the analysis to ensure there was no multicollinearity.

The model represented above substantiates the previous model of why students may consider enrolling in a more blended learning environment. Of the 10 variables of interest, seven variables were found to be significant in predicting enrollment in a 30:70 instructional delivery mode (versus other modes). Age remains a constant within the three tables. It appears that the younger the student, the more likely they may consider a blended option. Sex, race and volunteering do not seem to have any impact on student selection of course instruction. Students who reported higher levels of hourly employment (per week) were more likely to consider a 30:70 online instructional deliverable who may obviously require more flexibility and convenience.

It also appears that the number of classes and which classes students are enrolled in becomes a more significant variable as blended instruction applies. Students who were enrolled in three or fewer courses, considered the criminology course as an elective course and also having a lower GPA (corresponding to a C or lower) were more likely to choose the 30:70 option. Might this be due to students simply prioritizing other classes over this particular criminology course? Perhaps students registered for fewer courses equates to a lessening engagement of traditional materials if given the option. Unfortunately, it appears that these findings while being interesting does not explain the complexity surrounding the inter-connectivity of these variables. It also appears that a longer a student commutes to the university (from their primary residence) is also having an impact on their selection of instructional delivery. This variable in combination with taking fewer courses may be driving a student’s selection or preference to stay at home more or working more hours (where university courses are less of a priority).

The findings of these three tables offer some insight in how a student may be motivated to select a particular course instructional delivery. Linear and logistic regressions are often performed with sample sizes over 400 to ensure reduced multicollinearity. While three cases were removed from two analyses, results should be taken cautiously. Several variables were also not included from the sample profile due to a lack of variation in responses. A final anticipated discussion on a student’s motivations to take an almost completely online 90:10 course was also not analyzed due to a low sample size. These findings are conclusive however, it should be noted that due to a low size of this population, results should be taken as exploratory [41-50].

Implications

As other researchers have maintained, there is certainly a complexity surrounding how students select traditional, blended/ hybrid or online classes. While many of these motivations are often situational and/or circumstantial, this study offers an exploratory view on why students may self- select into one particular instructional delivery over another, if given the opportunity, It appears that age and race are demographic groups which were considered significant and require more research. We know that age could be directly correlated with confidence in computer literacy and/or more traditional face to face methods. However, more study is needed with perhaps more attention explored within what we know about distance learning. This study sought to learn more about commuting and distance education and it appears that a student’s commute to campus (the longer the commute) has an impact on their decision to choose a more blended offering of course instruction. The higher number of hours a student was employed through any given week in a semester was also a significant factor in blended learning instruction versus a lack of it. Flexibility and convenience was found to be a significant predictor of blended learning while also found to impact a more traditional face to face delivery (in a negative correlation). This might suggest that convenience may have more of an impact with blended learning rather than traditional face to face courses which is consistent with the literature. A student’s motivation to take more blended learning could be derived from the necessity of the class itself. It appears that students who enrolled in the class as an elective were more likely to consider more blended (70:30 or 30:70) options. This finding may have more to do with a student’s perception of how important the course is and the priority it is within a student’s liberal arts education within the institution studied. These findings offer a glimpse into self-selecting into an online learning environment. There are few studies that have offered such an insight into selecting one instructional method versus another and as such, more study is needed.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). ITU-WHO Joint Statement: Unleashing Information Technology to defeat COVID-19. Press Statement.

- Allen IE, Seaman J (2010) Class Differences: Online Education in the United States, 2010.

- Allen M, Bourhis J, Burrell N, Mabry E (2002) Comparing student satisfaction with distance education to traditional classrooms in higher education: A meta-analysis. The American Journal of Distance Education 16(2): 83-97.

- Biner PM, Welsh KD, Barone NM, Summers M, Dean RS (1997) The impact of remotesite group size on student satisfaction and relative performance in interactive telecourses. The American Journal of Distance Education11(1): 23-33.

- Brown BW,Liedholm CE (2002) Can Web Courses Replace the Classroom in Principles of Microeconomics? American Economic Review 92(2): 444-448.

- Johnson SD, Aragon SR, Shaik N (2000) Comparative analysis of learner satisfaction and learning outcomes in online and face-to-face learning environments. Journal of Interactive Learning Research 11(1): 29-49.

- Chickering A, GamsonFZ (1987) Seven Principles of good practice in undergraduate education. American Association of Higher Education Bulletin 39(7): 3-7.

- Gorsky P, Blau I (2009) Online Teaching Effectiveness: A Tale of Two Instructors. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3), Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press.

- Anderson T, Rourke L, Garrison RD, Archer W (2001) Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 5(2).

- Driver M (2002) Exploring student perceptions of group interactions and class satisfaction in the web-enhanced classroom. The Internet and Higher Education 5(1): 35-45.

- Conrad D (2005) Building and maintaining community in cohort-based online learning.Journal of Distance Education 20(1): 1-21.

- Akyol Z, Garrison R, Ozden Y (2009) Online and Blended Communities of Inquiry: Exploring the Developmental and Perceptional Differences. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 10(6): 65-83.

- Cohen KE (2012) Persistence of master’s students in the United States: Developing andtesting of a conceptual model. NY, NY University: PhD Dissertation.

- Beard L, Harper C, Riley G (2004) Online versus on-campus instruction: student attitudes & perceptions. Tech Trends 48(6): 29-31.

- Duffy T, Kirkley J (2004) Learner centered theory and practice in distance education:Cases from higher education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Allen I, Seamon J (2013) Changing Course: Ten Years of Tracking Online Education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group.

- Harden RM (2002) Myths and e-learning. Medical Teacher 24(5): 469-472.

- Liu X, Magjuka RJ, Bonk CJ, Lee S (2007) Does Sense of Community matter? An examination of participants’ perceptions of building learning communities in online courses. Quarterly Review of Distance Education8(1): 9-24.

- Yirtan Z, Breslow L (2013) Literature review on Hybrid/ Blended Learning.Teaching and Learning Laboratory. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Lack K (2013) Current status of research on online learning in postsecondary education.

- Means B, Toyama Y, Murphy R, Baki M (2013)The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta–analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record 115(3): 1-47.

- Noel-Levitz (2010) National online learners priorities report. 2010. Research Report.Coralville, IA: Noel-Levitz Incorporated.

- Jaggars SS (2012) Beyond Flexibility: Why students choose online and face to face courses in community colleges, Community College Research Center. Teacher’s College, Columbia University: Presented on April 12, 2012 at American Educational Research Association (Vancouver, BC).

- Colorado J,Eberle J (2010) Student demographics and success in online learning environments. Emporia State Research Studies 46(1): 4-10.

- Kahu ER,Stephens C, Leach L, Zepke N (2013) The engagement of mature distance students. Higher Education ResearchDevelopment 32(5): 1-14.

- Vermunt J, Vermetten Y (2004) Patterns in student learning: Relationships between learning strategies, conceptions of learning and learning orientations. Educational Research Psychology Review 16(4): 359-384.

- Chyung S (2007) Age and gender differences in online behavior, self-efficacy, and academic performance. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education 8(3): 213-222.

- Quinn F, Stein S (2013) Relationships between learning approaches and outcomes of students studying a first-year biology topic on-campus and by distance. Higher Education Research & Development 32(4): 617-631.

- Raidal SL,Volet SE (2009)Preclinical students' predispositions towards social forms of instruction and self-directed learning: A challenge for the development of autonomous and collaborative learners. Higher Education 57(5): 577-596.

- Koh E, Lim J (2012) Using online collaboration applications for group assignments: The interplay between design and human characteristics. Computers and Education 59(2): 481-496.

- Ke F (2010) Examining online teaching, cognitive, and social presence for adult students.Computers & Education 55(2): 808-820.

- Kummerow A, Miller M, Reed R (2012) Baccalaureate courses for nurses online and on campus: A comparison of learning outcomes. American Journal of Distance Education 26(1): 50-65.

- Boysen GA, Vogel DL, Cope MA, Hubbard A (2009) Incidents of bias in college classrooms: Instructor and student perceptions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 2(4): 192-219.

- Dawn B, Volkov M (2007) Assessment of online reflections: Engaging English second language (ESL) students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 23(3): 41-64.

- Conaway W, Bethune S (2015) Implicit Bias and First Name Stereotypes: What Are the Implications for Online Instruction? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 19(3): 162-178.

- Xu D, Jaggars SS (2013)The impact of online learning on student’s course outcomes. Evidence from a large community and technical college system. Economics of Education Review 37: 46-57.

- Xu D,Jaggars SS (2011) The effectiveness of distance education across Virginia’s community colleges: Evidence from introductory college-level math and English courses. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 33(3): 360-377.

- Yatrakis PG, Simon HK (2002)The effect of self-selection on student satisfaction and performance in online classes. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 3(2): 1-8.

- Garrison D, Anderson T (2003) E-Learning in the 21st century: A framework for researchand practice. London, UK: Routledge/Falmer.

- Twigg CA (2003) Improving learning and reducing costs: New models for online learning. Educause Review 38(5): 28-38.

- Needham, MA: The Sloan Consortium, pp. 1-26.

- Beqiri MS, Chase NM, Bishka A (2010) Online Course Delivery: An Empirical Investigation of FactorsAffecting Student Satisfaction. Journal of Education for Business 85(2): 95-100.

- Anderson T (2004) Theory and Practice of Online Learning. Canada: AU Press, Athabasca University.

- Colachico D (2007) Developing a sense of community in an online environment. International Journal of Learning 14(1): 161-165.

- Demirkol M, Kazu IY (2014) Effect of blended environment model on high school students’ academic achievement. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology 13(1): 78-87.

- Ferguson JM,DeFelice EA (2010) Length of Online Course and Student Satisfaction, Perceived L earning and Academic Performance. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 11(2): 73-84.

- Garrison D (2009) Communities of inquiry in online learning: Social, teaching and cognitive presence. In: C Howard, et al. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of distance and online learning. (2ndedn),Hershey, PA: IGI Global, pp. 352-355.

- Kwak D, Menezes F, Sherwood C (2013) Assessing the impact of blended learning on student performance. Educational Technology & Society 15(1): 127-136.

- Rovai AP, Barnum KT (2003)Online course effectiveness: An analysis of student interactions and perceptions of learning. Journal of Distance Education 18: 57-73.

- Shea P, Li C, PickettA (2006) A study of teaching presence and student sense of learning community in fully online and web enhanced college courses. The Internet and Higher Education 9(3): 175-190.