The Crisis of our Time: Return to the Man and to Humanistic Culture

Fabrizio Pezzani*

1Professor of Marketing, University of Denver, USA

2 Cornell University, USA

Submission: September 16, 2019; Published: November 14, 2019

*Corresponding author: Fabrizio Pezzani, Bocconi University, Italy

How to cite this article: Fabrizio Pezzani. The Crisis of our Time: Return to the Man and to Humanistic Culture. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2019; 4(4): 555644.DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2019.04.555644

Abstract

The debate on economics and its methods of study cannot be separated from a correct reading of history that in the long term tends to repeat itself, as G.B. Vico had envisioned; the nature of man never changes, constantly oscillating between Cain and Abel, and it would seem that only pain leads man to wisdom. The single technical-rational thought makes us see the future as the only guarantee of success and we therefore cannot understand the correlations between the causes and effects in our history. The debates on the role of studies in economics, and in particular finance, are broader and must be ascribed to a historical framework to understand how these have contributed to an acceleration in the change of a socio-cultural model that has collapsed but has its distant roots in the field of speculation

The History’s Lesson: Anthropological Crisis Not Economic

The School of Athens that Raphael painted starting in 1508 when, aged 25, he was called to Rome by Pope Julius II. Raphael grew up during the Italian High Renaissance and drew (Figure 1). The leading lights of that era are all there, gathered around the two central characters: Plato, his finger pointing skywards to indicate the world of ideas and the spirit, and Aristotle, who instead stretches out his hand palm down to indicate the real world and scientific experience. The world of ideas and the spirit can never be divorced from an empirical quest for truth. So, everything must be focused on a search for what is true, for beauty, to promote the primary aim: the fulfilment of human happiness. But the world was by no means a paradise in either ancient Athens or in Raphael’s time. Both were times in which life was generally extremely hard, unrefined, times of trepidation and suffering. And yet despite these conditions human beings managed to achieve moments of sublime creativity.

Today we ought to be in a completely different situation from that of Plato and Raphael, thanks to the progress and power of technical knowledge. A knowledge which has become an end in itself for the modern world, one that should have provided answers to satisfy our primary needs, releasing us from our “shackles”, reducing inequalities, freeing us, at least in part, from a life of fatigue and suffering in physical terms. Scientific knowledge should have helped to create a situation in which our free, inventive mind could once again be the driving force of life, leading us to that dimension of spiritual joy we admire in splendid works of art.

This is what Keynes thought would happen. In his essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren written in 1930 he said: ‘Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem – how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, which science and compound interest will have won for him [...]. The love of money as a possession – as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life – will be recognized for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease’.

Sadly, this has not been the case, in fact, the very opposite has happened. Technical-instrumental knowledge has become moral knowledge, an indisputable truth and so in no way open to discussion. It dictates the rules for everyday life to the point that humanity itself has become its instrument. The technical culture of modern times has failed to achieve the aim that was hoped for. However, it is not the culture that is at fault but the improvidence of Homo sapiens.

We have failed to redistribute wealth; inequalities, famine and poverty have increased; we have not resolved major health problems afflicting a majority of the world’s population. Technical knowledge has separated us from our souls, made us sterile and impersonal, incapable of true human relations and the profound sentiments of love and joy. Unless, that is, these are linked to the sole satisfaction of material and fleeting pleasures. We have imprisoned thought, disintegrated family bonds and forced youngsters to roam the streets without hope. All of us have made this mistake, given that responsibilities are always personal, even if at different levels. This modern age needs rethinking if we are not to find ourselves once more facing chaos.

The first step we must take is to ask ourselves if all this talk about the economy being the cause of the crisis of these times is really true. Can we continue to think that all the misfortunes mentioned previously are the result of the malfunctioning of rules governing the economy? Or should we admit that a cultural model which has produced the opposite results to those intended has collapsed?

Our lack of a social and spiritual life, of creative and intuitive thought, the drabness of an existence in which we are no longer capable of questioning the meaning of life itself ‒ can all of this depend on a malfunctioning of the economy? We urgently need to review our recent history. We have to question the role we have assigned to the economic sciences and methods of study these have been based on for the past thirty years. Methods effectively founded based on the fundamental idea that economic sciences and the underlying choices and decisions involved are “totally” independent from human nature. So, this means our emotions have no bearing on these choices and decisions. The assumption has therefore been that given equal conditions and information the results will always be the same, thereby endorsing a rational approach that cannot be questioned.

The time has come to understand that we are facing an anthropological and not economic crisis as it is reductively defined; it is the failure of a socio-cultural model that has erased the fundamental human rights inscribed in 1948. The response to the crisis as anthropological is in understanding the cultural and historical path that has brought us to chaos, overthrowing the dominant paradigm, to place man and society at the center of our interests as an end and to bring economics back to its natural role as a means [1-10].

The technical culture, master of the world has unnaturally transformed economics as a social science into an exact science; in the exact sciences we study the relationships between measurable things to define universal laws, but in the social sciences, such as economics, we study relationships between men where human subjectivity does not allow defining universal laws. Von Hayek in his Nobel acceptance speech in 1974 denounced the serious mistake that would pave the way for rational finance and speculative markets distant from the real world; but here mained unheard: “‘It seems to me that this failure of the economists to guide policy more successfully is closely connected with their propensity to imitate as closely as possible the procedures of the brilliantly successful physical sciences – an attempt which in our field may lead to outright error. […] This brings me to the crucial issue. Unlike the position that exists in the physical sciences, in economics and other disciplines that deal with essentially complex phenomena, the aspects of the events to be accounted for about which we can get quantitative data are necessarily limited and may not include the important ones’.

Hayek’s warnings didn’t manage to halt the diffusion of a model that we could define as “the mirage of rationality”. Today we find ourselves having to face the failure of a model that has separated the nature of people from the results of their activity. We have ignored six thousand years of history with an arrogance that can only have been inspired by the hubris of technical science and interests that the latter ought to have legitimated (Figure 2).

The inseparable bond between the technical culture and economics, as recognized and studied, leaves the door wide open to humanity’s ancestral greed. A limitless hunger for profit realizable only through material goods. It creates the very system we are prisoners of today and is the source of a deadly risk. The risk of a society in which we become objectivized and lose all sense of ourselves, of our life, our feelings and creative ability. It is artistic masterpieces that show how our most intimate being is rooted in a sense of creative spirituality as opposed to being concerned exclusively with an obtuse rationality for its own sake.

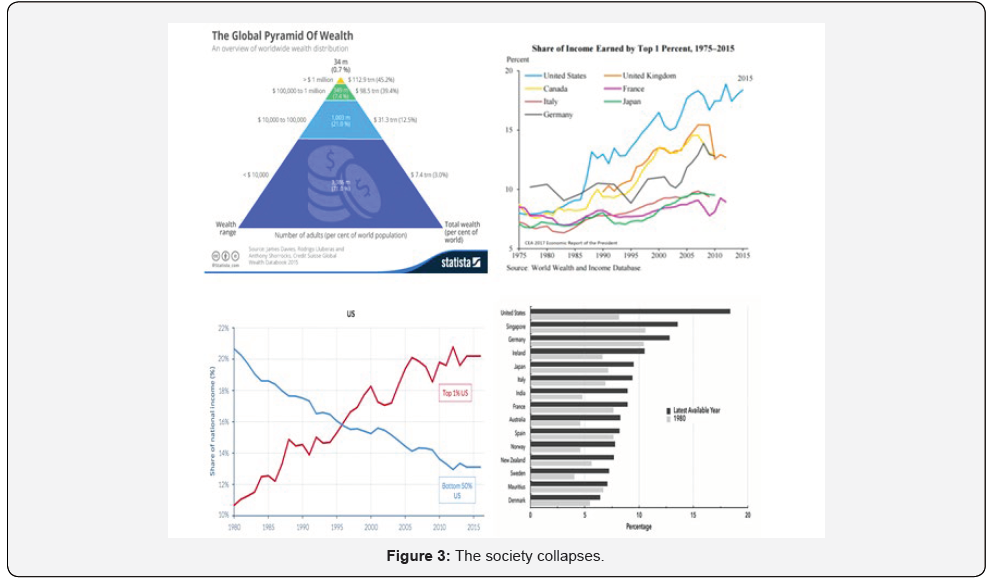

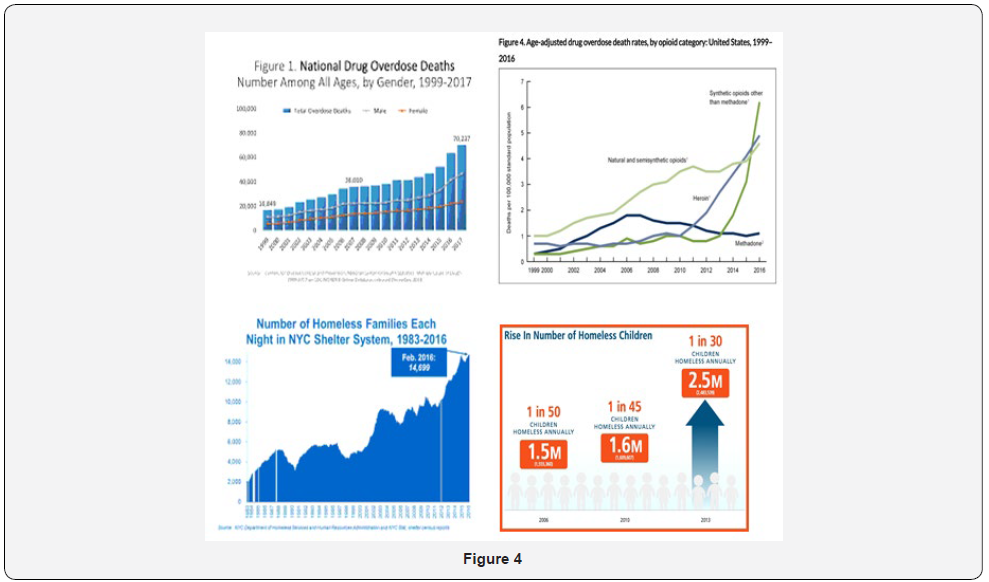

So today the time has come to again make economics a tool and not an end in itself. A process must be launched to humanize it, abandoning the absoluteness of a rational approach that repudiates history. Rethinking our role and the sense of our life is the real challenge we must face all together, for ourselves and for future generations. We have a biggest inequality in the history, and we can’t stay longtime in this moral disaster as we can see: (Figure 3 & 4).

Society is a foundation of the economy: the inequality is the end of a society in the history. Given such conditions, which are very similar to the current situation, it is understandable that as the oppressed become more aware of their situation they develop an intense hostility towards the society that is oppressing them. History clearly shows this, as was commented by Sigmund Freud in The Future of an Illusion, published in 1927. He noted that when a society fails to overcome the stage in which satisfying a certain number of its members requires oppressing the others, perhaps the majority, it is understandable that the oppressed develop an intense hostility towards society. A society in which they are allowed to work but from which they receive an insufficient part of what is produced. It should be obvious that a society that leaves such a large number of its members dissatisfied induces them to revolt. Such a society has no prospects – nor deserves – to last very long. These considerations forced Freud to see the socialist movement as not being an attempt to create paradise on earth but as a move to reduce oppression [11-20].

From this point of view Marx was right in saying that when capitalism is an end in itself and the main focus is individual interest, this will lead to a concentration of wealth in few hands and, as such, is likely to provoke the reaction of everyone else. This is why he believed that the final phase of this type of individualistic capitalism would be socialism, emerging as the natural outcome of a need to re-establish more equality within society.

This right to equality appears to be strong in the United States’ Declaration of Independence and its Constitution that, at the time, were a response to oppression by the British crown. Today, however, it looks as though this right has really been forgotten in a society that seems to be facing sociocultural default. US society is fraught with an unprecedented level of social issues and inequality. It should be mentioned that the term society is intended in the widest possible sense to indicate all associative forms devised by human beings. The term is derived from the Latin societas, meaning alliance, which today has instead been given an economic and commercial weight far removed from the original meaning. As intended in Latin the term is less impersonal than the word “institution” used in legal contexts, inasmuch as the intention is to highlight the role of individuals and especially the determinant that influences their choices, namely, human nature. A nature that has not changed from how the Greek dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides so masterfully presented it in their tragedies. It was Euripides who in 405BC, de facto, first introduced the theme of the unconscious in The Bacchae, a theme that Freud was to take up again over 2,200 years later.

As will be seen throughout this book, the above clarification is important given that it highlights how the essence of human nature is the true driving force of history and the cause of crises that have developed over time. History shows us that change can take a long time and seems to follow a non-linear, alternating course. One that tends to repeat itself based not on material conditions but on an immutable factor, human nature.

Today we are distracted by the daily occurrence of sensational facts and a focus on a future founded solely on technical progress, believed to be the guarantee of success. We are losing the ability to comprehend the long periods of time over which history develops because we continue to think of it as independent from the factor that creates it, people. But is it possible to study the results of people’s actions without knowing their nature? Is its human nature to be exclusively rational as modern economics assumes? Are study methods based on the former assumption well founded?

So, in this interpretation of the crisis the proposal for cooperative competition not only has a technical-economic value but is also intended to include the social dimension. This is by no means a contradiction in terms as it might seem to be at first sight but an attempt to create a synthesis of the unceasing forces that have always been the mark of human nature. The never-ending battle between our genetic aggressiveness – competition – and the idea of mitigating this impulse to allow for the need to be social – cooperation [21-24].

It is, in other words, the eternal battle between the forces of Eros, exactly as Plato intended it in the Symposium, written in about 385 BC, and Thanatos, that tends to destroy, to kill. Both are necessary, both are part of our biological make-up and life proceeds based on a confrontation of these forces. However, the inability to reconcile them is disastrous. It should be clarified that these two forces are different from the concept of good and bad, which are moral categories of a higher order.

What is needed is a form of competition based on cooperation, one that creates unity and attempts to reconcile our deeply felt needs (social interest) as opposed to competition as proposed in the market model (individual interest). Today the latter is considered a must, one that tends to give rein to the more aggressive side of human nature and a limitless ancestral greed. A greed that if unchecked would even make people feel restless in paradise!

In this absolute interpretation of the market individual interest prevails to a point where the sociocultural model, taken to the extreme, degenerates and ends up by disintegrating all forms of human organization. In fact, throughout history societies have always been destroyed by class differences and wars. The alternation of Chinese dynasties over the millennia and their history are a prime example of this. No dynasty was ever overthrown by an external conqueror but because of the dominance each of them exercised over peasants, who were exploited to an intolerable degree in order to create the grandiose works we can still admire today. But the Great Wall was also known as the great cemetery and building it ended up by causing peasants to revolt. The result, however, was that one dynasty was replaced by yet another that, forgetting the errors of the past, eventually came to the same end as its predecessor.

Currently our sociocultural model is marked by conflictual individualism and a consequent inequality unprecedented in history. The USA is the most evident example of this; indeed, it is fueling and giving substance to two factors – class differences and war – two congenital ills and fatal calamities seen throughout history. Up until World War II social inequalities were considered natural, but then after the war the search for and expression of democratic values to counter previous absolute regimes became widespread. Today, also thanks to the media, these are considered an unacceptable injustice.

In postwar years the USA developed an extreme example of the capitalist economic model, whereas Europe continued to pursue a more cooperative competitive model. Today these represent two different cultural models that are now engaged in a battle fought with the arms of finance.

In fact, Western society is no longer the one united front it had appeared to be prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Before this the presence of an external enemy contributed to reconcile differences between the two cultures. There was the market culture focused on achieving maximum short-term individual gain – primarily the US culture – and that of subsidiarity more similar to European culture, which focused on achieving a maximum medium/longterm gain for the system. Following the implosion of the USSR the contradictions and gap between the two models became evident as their aims are entirely different and implementing one excludes the other.

It is unthinkable to simultaneously implement a capitalist model that aims to maximize profit by means of massive recourse to the financial economy (the market model) and another aimed more at the common good and oriented towards the real economy (the subsidiarity model). Clearly the means to achieve each model are entirely different. ‘No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or else he will be loyal to the one and despise the other’. (New Testament, Matthew 6: 24-34)

In order to simplify their propositions and analyses of facts to the maximum they only take into account what is measurable. But given such a complex situation as a society, it would suffice to observe how decisions are made in a family to understand that they are on the wrong track. Data gathered are entirely insufficient given the complexity of what is to be evaluated, but even so they are considered as absolute. And as the cultural benchmark mentioned cannot be debated, the end result is that we are victims of a groundless cultural tyranny, however, one that suits the purpose of those who gain a specific benefit from it.

As the presumed truth is absolute, financial analysis’ models consider it irrelevant if members of a society facing economic problems can deal with them or not. However, if we accept the basic premise of this book, namely, that society is the foundation of the economy, then clearly these models are anti-historical. Given the same financial indicators, is a society with a high “equality” or high “inequality” as regards income more sound when facing a crisis situation? Can a family remain united if its members are in permanent disagreement? Can it remain united if the chief breadwinner uses its income to satisfy their own superfluous needs, so leaving other members of the family permanently dissatisfied?

In effect rating agency models of analysis are inadequate because they pretend that reality adapts to their own self-serving ends. How can they think it possible to evaluate such a complex system as a society every ten days basing this solely on cash flow? And in the light of these considerations, how is it possible for the USA to be given a triple A rating when it is on the verge of social default? Although having said this we should remember that Lehman Brothers had a triple A rating up to the day before the crash. Rating agencies get there late and perform badly, and this quite rightly generates a natural diffidence towards their ratings. These end up seeming more opportunistic than well-founded. In turn this increases instability in markets and contributes to confirming the truth, namely, that markets are not rational. Agency ratings and the timing with which they are issued, and more often than not the fact that they are unrealistic, could, in the light of the facts, justify a class action being brought against them.

Today we are indeed seeing the success of a highly liberalist and capitalist sociocultural model, taken as being “indisputably true” and based entirely on a technical-rational philosophy. The result is a mainly conflictual and aggressive society that aims to maximize short-term gain for single individuals or groups of individuals. And in turn this produces an individualistic, antiegalitarian society in terms of redistribution of wealth.

It is exactly the increase of inequalities, as we will see in the USA, which increases the level of conflict. This makes the consequent social issues and costs worse, and these then boomerang back against the system. In several US states, for instance, the cost of the prison system is higher than that of secondary education. The current model has ended up by creating a crisis in the middle class, the class that really “primes the pump” in our societies. But if a crisis exists for a significant minority of our societies, inevitably there will be a crisis for everyone else. This book holds that the true, deep-rooted causes of the crisis we are experiencing can be found in this sociocultural model now on the point of collapse. A model incapable of providing an answer for society’s real needs. We fail to see that the origin of today’s crisis all began way back, in the history of philosophy and in the field of speculation. Instead today we are used to always linking negative or positive facts to the last event that occurs.

Is Economy Positive or Moral knowledge?

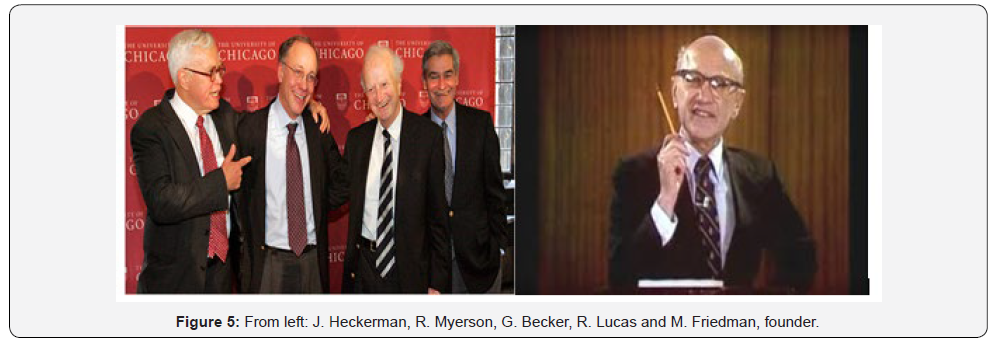

The Nobel award and the illogical contradictions and the dramatic mistake: John Maynard Keynes (Bretton Wood 1944) and Frederik von Hayek (Nobel in 1974) affirm: “ Economy is social science and human nature is emotional and not rational. The emotion drives the human choices in economy.” But Robert Lucas was in 1995 Nobel Prize in economics “for having developed and applied the hypothesis of RATIONAL EXPECTATIONS, and thereby having transformed macroeconomic analysis and deepened our understanding of economic policy”. The man is rational and financial markets never wrong in wealth allocation because the traders having the same information’s decide, always, at same way. (totally illogical !!!) (Figure 5).

The Chicago School became the truth against the Real world but: Where ’is the truth? We have two Nobel prize totally asymmetric, but “A” can’t be at same time “Not A. The monetarism ‘school find in Chicago the roots; most monetarists oppose the gold standard; Friedman, for example, viewed a pure gold standard as impractical. For example, whereas one of the benefits of the gold standard is that the intrinsic limitations to the growth of the money supply by the use of gold would prevent inflation, if the growth of population or increase in trade outpaces the money supply, there would be no way to counteract deflation and reduced liquidity (and any attendant recession) except for the mining of more gold. Monetarism affirm as incontrovertible true that the paper - money has value in itself without real value; with monetarism we have the biggest bubble in finance in the human history. Today we can see the monetarism nemesis: the passive interests and the financial chaos.

This has been legitimated by a culture claiming that the sole principle of truth is “what we can see, touch and measure”. In fact, while physical reality is measurable, spiritual and emotional reality is not, and so the perimeter that defines the measurement becomes clouded and irrelevant when used for decisions. Terms like ethics, solidarity and justice risk being incomprehensible for young people and, unfortunately, not only for them. Ethics, for example, differs from science ‘by the fact that its fundamental data are feelings and emotions, not perceptions. This is to be understood strictly; that is to say, the data are the feelings and emotions themselves, not the fact that we have them. [...] Thus ethics is bound up with life, not as a physical process to be studied by the biochemist, but as made up of happiness and sorrow, hope and fear and other cognate pairs of opposites that make us prefer one sort of world to another’. (Bertrand Russell, Human Society in Ethics and Politics, 1954) But if the truth that asserts itself were solely of the physical-material type then this could be explained exclusively by the physical sciences. As these are based only on the measurability of events to be examined and that, in turn, end up by becoming truth, as a result our spiritual dimension becomes confused and indefinable.

So, we have let technical knowledge win hands down and over time have recognized it as moral knowledge – to be the indisputable truth. As always, the problem is not the tool itself but the fact that it has become beyond discussion. The final step, the one that closed the circle, was to extend this study model to also cover social sciences like economics. Progressively the principle was introduced that, as in natural sciences, study models are independent from the reality of what is being studied. This has encouraged the idea that the perfection of exact sciences is able to explain social phenomena, also by ignoring our emotional dimension – the mirage of rationality – and study of human sciences, which have always been the foundation for the development of societies.

But when our philosophy is an integral part of the reality in which we live the separation ceases to exist, because our decisions will always be conditioned by our nature, which expresses emotional expectations. We, in fact, are not just rational beings, our emotional drives prevail. Even though for the purpose of economic theory it was convenient to imagine us to be solely rational, until, that is, reality rebelled against this.

This rift is even more evident in financial economics because decisions are based on expectations and not on knowledge, as in the case of natural sciences. So-called “reality” is not based on definite knowledge and therefore the gap from the real economy encourages a propensity for human weaknesses, euphoria and depression. Financial markets may seem to anticipate future events exactly whereas it is expectations of future events that rule markets. However, the assumption is that people, when faced with a problem and given the same information, will all decide in the same way, despite their individual differences. This has become the basic premise for modern economic studies – sic et nunc.

In this way we have inverted the roles of subject and object in economics and finance. People no longer define their choices based on needs, their priorities and means by which they intend to satisfy them. Today it is the technical-economic truth that dictates priorities and we just have to put up with it. We have become the dependent variable and the economy the independent variable. So, we have produced a system that is external to humanity, one that feeds on itself and continuously creates antibodies in order not to be questioned. In short, we have become “economized”.

In the end the technical-rational philosophy has suffocated creative and intuitive thinking. We have returned to a kind of Alexandrian culture; industrious, scientific, devoted only to facts, but incapable of making any really important discoveries as regards human nature or of creating even one true value. Not one general theory has been produced since the time of Keynes. Indeed, it was Keynes in 1926 who in The End of Laissez-faire said, ‘A study of the history of opinion is a necessary preliminary to the emancipation of the mind’. The aim is to pursue the maximizing moral good, that is, to maximize the value of interpersonal behavior, such as personal affection, truth and beauty.

The idea of the perfection of exact sciences has created the illusory feeling of a power to organize a future free from uncertainty, one capable of dispelling pain and prolonging pleasure indefinitely. But as Freud maintained, we are governed by both the reality principle and pleasure principle and only by facing the pain caused by this can we grow and acquire the knowledge of truth. (‘Learn through suffering, suffering teaches’, says Sophocles in Oedipus Rex, c. 429 BC, drawing on Aeschylus and his concept of pathei mathos [personal experience is the genesis of true learning]. Suffering in Greek culture was linked to understanding oneself – “Know Thyself” was the inscription on the temple of Apollo at Delphi – and the painful acceptance of one’s own limits).

To see physical reality as being separate from the human emotional level – as a result of which we become objectivized – and to pursue this as an absolute truth makes it difficult to understand the real causes of the crisis. And so, we end up by attributing them to technical-type problems – regulating markets and currency, labour reform, unemployment, social security, redefinition of the model of the state or for growth, bureaucracy, etc. According to this concept the crisis can only be resolved by mechanistic measures outside of society, which in this model is considered a dependent variable.

But if instead we realize the crisis depends on a model of social cohabitation that has collapsed as a result of having created a conflictual and unequal society, then the way we can hope to overcome it changes completely. It will require the ability to understand how to reorient the model of life and values of our society and our humanity. We must once again be given the role of key players in decisions affecting our lives. In other words, we cannot continue to think of changing society by means of what are believed to be indisputable external rules, and by adapting it to them. If we look at real life we can clearly see the inadequacy of these cultural models to answer the real problems. The more economists devote themselves to the economy, the worse this gets; the more experts in social sciences involve themselves with society and families, the more these situations deteriorate; the more political scientists focus on politics, the worse the crisis gets; the more we worry about reducing crime, the more it increases; the more the number of graduates increases, the more true culture and an understanding of problems diminishes; the more research and abundance of data increases, the more uncertainty of how to interpret them increases; the more opportunities to communicate increase, the more isolation of individuals increases. The reality of all this is evident, but it seems we have become incapable of seeing it. In our frenzied effort to look exclusively at infinite series of measurable facts using mathematical and statistical formulas we have ended up by knowing “more and more about less and less”. We have lost sight of the essential things we should really be looking at. Paradoxically, it seems the more knowledge we have the less able we become to respond to problems, we seem to have created what could be called a “law of diminishing returns”. We have entered an era of growing uncertainty in which truth seems to change all the time and theories are continually modifiable. Theories that rationalize values and create a social illness expressed as an existential discomfort that can corrode our spirit and end up paralyzing us.

References

- Cicero (1999) On the Commonwealthand on the laws. Cambridge University Press, England.

- Aristotele (2000) EticaNicomachea [Nicomachean Ethics]. Bompiani, Milan, Spain.

- Chomsky N (2006) Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy. Il Saggiatore: Milano, Spain.

- Guardini R (1954) The End of the Modern World. Morcelliana, Brescia, Italy.

- Keynes JM (1923) The End of Laissez Faire. MacMillan Publishers, London, England.

- Keynes JM (1933) Essays in Persuasion. MacMillan, London, England.

- Pezzani F (2011) Cooperative Competition. Egea-UBE, Milan, Spain.

- Pezzani F (2016) The Nobel Prize for mythical finance and Colombo’s egg. Bus Econ J.

- Pezzani F (2016) Independence Day and forgotten equality. Bus Econ J.

- Pezzani F (2017) The gold exchange standard and the magic trap of paper money. J AccounFinan Audit 5(4): 23-32.

- Pezzani F (2017) Once upon a time in America and the end of the American dream. Journal of Socialomics 6: 3.

- Pezzani F (2017) Society the foundation of the economy. We need a sociocultural revolution. Scholar’s Press, Germany.

- Posner R (2010) The crisis of capitalist democracy. Egea-UBE: Milan, Spain.

- Prigogine I (1996) La fin des certitudes. Temps, chaos et les lois de la nature. Odile Jacob, Paris, France.

- Putnam R (2004) Social capital and individualism. Il Mulino, Bologna, Italy.

- Russell B (2009) The scientific outlook. Laterza, Rome-Bari, Italy.

- Sigmund F (1971) The Discomforts of Civilization. BollatiBoringhieri, Turin, Italy.

- Sigmund F (1971) The Future of Illusion. Boringhieri, Turin,Italy.

- Sorokin P (1941) Social and cultural dynamics. Utet, Turin,Italy.

- Sorokin P (1941) The Crisis of our age. EP Button & Co, New York, USA.

- Toynbee AJ (1949) Civilization on trial. Bompiani, Milan, Spain.

- Toynbee AJ (1977) Mankind and mother earth. Garzanti, Milan, Spain.

- Vico G (1725) La scienzanuova [The New Science]. Napoli.

- Zygmunt B (2005) Liquid Life. Laterza, Bari, Italy.