Is Education an Investment for the Future? The Impact of the Greek case on Economic Growth

Costas Siriopoulos1* and Sophia Kassapi2

1 College of Business, Zayed University, UAE

2Institution for Preschool Education, Greece

Submission: June 21, 2019; Published: July 17, 2019

*Corresponding author: Costas Siriopoulos, School of Business, Zayed University, UAE

How to cite this article: Siriopoulos C, Kassapi S. Is Education an Investment for the Future? The Impact of the Greek case on Economic Growth. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2019; 3(5): 555622. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2019.03.555622

Abstract

In this paper, we study the long-run causal effect of public investments in schooling for the country of Greece by applying econometric techniques in order to investigate if there is an economically significant long-run relationship between school entrants at all levels and economic growth . Following the EU policy advice for Greece our study attempts to support the reform process of the education system as suggested, highlight those signals of ineffective investments and focus the attention of the investment policy in education on the needs of the knowledge economy, in order to guarantee the profitability of the financing funds. In an international and extremely demanding and dynamic framework, and in the European system of education and training in whole Greece is an important stakeholder that demonstrates a major embedded interest in higher academic studies and should be looked upon as such. Finally, we cast doubt on the notion that a strict financial adjustment program can induce sustainable development and boost economic growth.

Keywords: Returns to Education; Economic Growth; Sustainable Development; Government Expenditures

Introduction

The interest for the economic benefits of education is dated back in the era of industrial revolution, and the times when Adam Smith in 1776 suggested educating the workers. Education, he said, drives away all the disarray and discontent. Generates a self-interest in the person and thus improves its levels of productivity. After a very long period, education is again a key factor for production, development and growth. Theodore Shultz (1963) with his work on human capital and the economic value of education, the focus of Gary Becker [1] on the critical role of education on human capital formation, and the seminal work of Jacob Mincer [2] and his earnings regressions made a restart to the issue of economics of education and the creation of human capital as a major research field. Recent literature though proves that, the assumptions of Mincer model for the 1960 labor market are no longer strong and for that reason the model is not able to grasp the current conditions. Mincer’s belief that markets operated under perfect certainty, and that individuals were facing no direct costs other than their time (a free good), misled him and the method was biased.

Most instrumental variables also, tend to correlate with individual cognitive abilities, violating the fundamental hypothesis of freedom e.g. family background correlating with IQ measurement not illustrating the real ability of the person under examination, with maybe the only exception that of the measurement of local labor market unemployment, which reflects purely e.g. the unemployment of the educated due to a clear mismatch with the low skills in demand. Available data sets of education and earnings do not include separate measurements of the cognitive ability of individuals, in which case it is included in the residuals, implying not accurate results. All studies have approached the contribution of educational expenditure to growth very sufficiently but none of them has ever managed to quantify other individual characteristics that refer to the family, such as particular features of the person etc.

Even fewer are the studies that are directed towards the social and economic structure of an economy and its comparative advantage. Asteriou & Siriopoulos [3] in a study on Greece they studied the Greek educational system and found that emphasis is needed on vocational higher education for the 1960-1994 period. A consecutive study on the causal effect of education on economic growth [4,5] in Greece for the 1960-2015 period showed a rather weak causality on the country’s gross domestic product implying the need for a comprehensive educational reform in terms of curriculum and funds, adding to the finding that vocational education should be outlined.

In a whole, the literature on the relation of years of schooling and growth is positive. But the average level of years of schooling as a variable might be both misleading and inadequate, in international as well as in national level, when used in the comparative study of human capital among countries. Also, another important issue is the unobserved heterogeneity on a national level meaning that e.g. the cultural values of a country that will be missing from the econometric model, will in the end result in inaccurate findings derived from the education production function. As very often is the case, one year of school attendance in Europe happens to be in many respects different from one year in Asia, or between countries for example. The comprehension of the way individual agents decide on the way they will distribute their wealth upon the cultivation of themselves and their families is something that remains vague.

Discussion

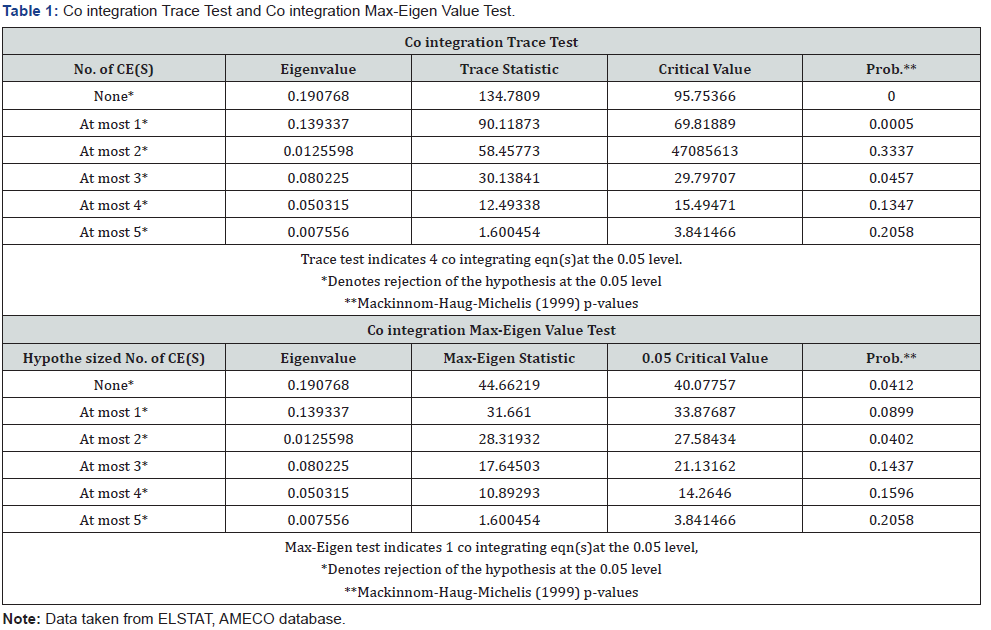

In the process of looking for economic meaningful causal relations Linear and Nonlinear Granger causality tests were applied. Except for the classic Engle-Granger test, Diiks and Panchenko non-parametric methodology for both unidirectional (asymptotic) and bidirectional (bootstrapped) causality was adopted. Johansen Cointegration testing gives us the existence of of cointegrating vectors (Trace statistic) justifying the equilibrium relationship that exists between them. It indicates the existence of 4 cointegrating vectors, which is the signal that allows us to continue further with the analysis. The fact that the random walk of our variables, is relatively not that random at all, is immediately translated as a very close relationship at hand (Table 1).

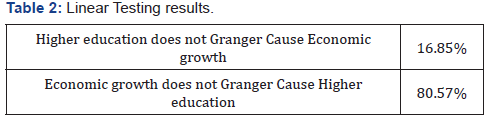

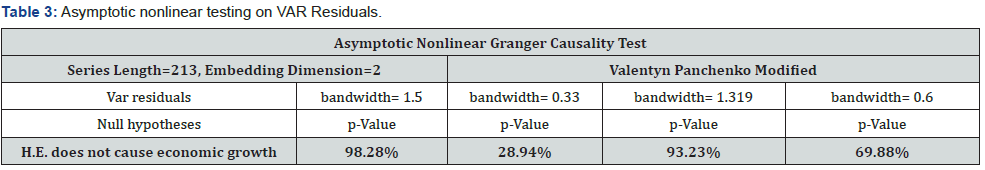

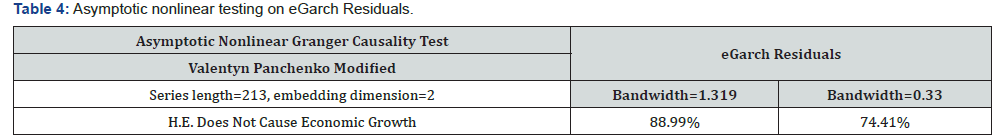

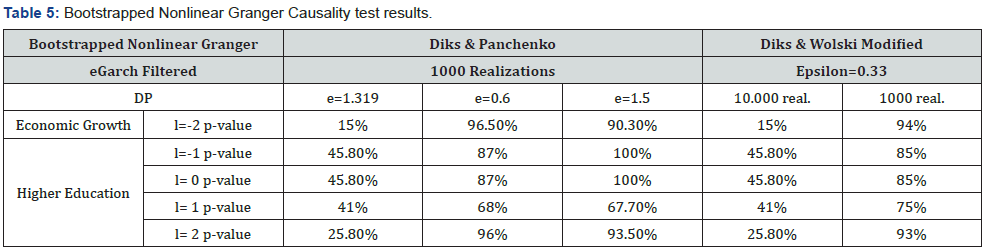

Max-eigen statistic indicates one cointegrating relationship, which again confirms our hypothesis, and allows to go further with the procedure of causality testing. We examined the dynamic relationship between GDP per capita, public expenditures in education and students’ enrollments of all 4 levels namely preschool, primary, secondary and tertiary education for Greece in the 1960-2015 period. Compared to the results of the Asteriou & Siriopoulos [3] study causality now appears to be weak especially for the case of Higher education (Table 2-5).

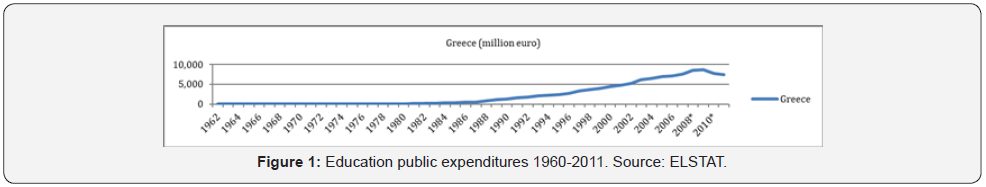

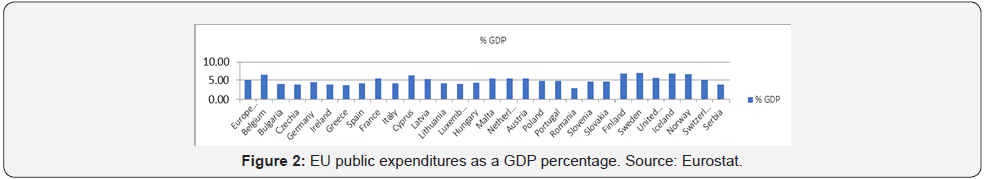

Until today Greece has been following a rather moderate rate in education expenditures as of 1960 and on (Figure 1). Part of this is attributed to European directive of education funding of the EU-average of 5% (Figure 2) which has been followed by almost every European country [6,7].

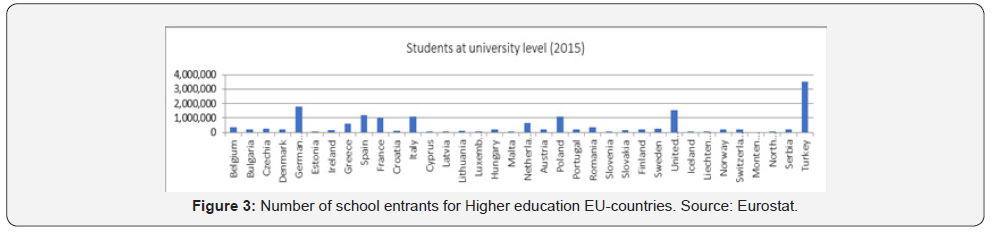

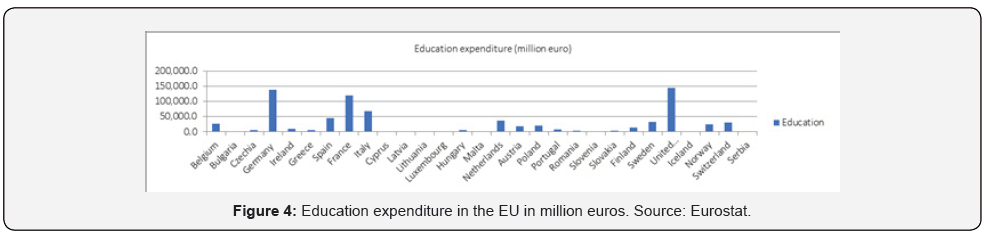

In terms of current prices and when compared with other European countries to the number of school entrants especially for Higher education it does not go according to the raw numbers (Figure3). For a number of 600.000 HE students Greece has been spending a 4.4 % of its GDP , when at the same time France with 1.000.000 students spends 10 times as much in million euros (Figure 4) and the Netherlands with almost the same number of students spends at least 4 times more but all three countries follow the equivalent of 5% of GDP [8,9].

Conclusion

In the era of knowledge economy, interest in education must be of greater importance. Students pursuing further with their studies can provide the pedestal for a stronger economy and a better skilled labour force. Human capital is and will continue to be a driving force for businesses. The education system in Greece needs to adopt a more comprehensive investment policy in order to reply to a great number of individual agents who believe in augmenting their utility through schooling.

References

- Gary S Becker (1964) Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. Columbia University Press. pp. 145-190.

- Mincer J (1974) Schooling, Experience and Earnings, Columbia University Press for NBER. New York, USA.

- Asteriou D, Siriopoulos C (1997) Can Educational Expansion Function as A “Seed” Of Economic Development in Developing Countries? City University. Department of Economics and Applied Econometric Research Unit. Discussion Paper Series. p. 68.

- Kassapi S (2016) The Long-Run Causal Effects of Public Investments: Economic Growth and the Provision of Schooling. Greece 1960-2015. Parametric and Nonparametric Approach. Doctoral dissertation. pp. 1-435.

- Kassapi S (2017) Long-run Causal Effect of Greek Public Investments. In: Bilgin M, Danis H, Demir E, Can U (Eds.), Regional Studies on Economic Growth, Financial Economics and Management. Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics 7: 215-229.

- Panayotis Alexakis, Costas Siriopoulos (1999) The International Stock Market Crisis of 1997 and the Dynamic Relationships Between Asian Stock Markets: Linear and Non‐Linear Granger Causality Tests. Managerial Finance 25(8): 22-38.

- Cees Diks, Marcin Wolski (2016) Nonlinear Granger Causality: Guidelines for Multivariate Analysis. Journal of Applied Econometrics 31: 1333-1351.

- Granger CWJ (1969) Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods. Econometrica 37(3): 424-438.

- Cees Diks, Valentyn Panchenko (2006) A new statistic and practical guidelines for nonparametric Granger causality testing. Journal of Economic dynamics & control 30(9-10): 1647-1669.