Evaluating the Performance of Applicant Position in Firm

Zeeshan Maqsood1*, Sana Jawad2 and Tehreem Jawad3

1Department of Statistics, University of Sialkot, Pakistan

2School of Business and Economics, University of Management and Technology, Lahore

3School of Business and Economics, University of Management and Technology, Lahore

Submission: May 13, 2019; Published: June 11, 2019

*Corresponding author: Zeeshan Maqsood, Department of Statistics, University of Sialkot, Pakistan

How to cite this article:Zeeshan M, Sana J, Tehreem J. Evaluating the Performance of Applicant Position in Firm. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2019; 3(4): 555618. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2019.03.555618

Abstract

This study aims at identifying the most relevant indicators for evaluating the performance of applicant position in firm by using the factor analysis. A total of 245 observations and 15 variables are covered. Quantitative and Descriptive study is carried out in this research. Statistical technique of factor analysis was used for data analysis. In the process of that technique, the overall suitability of the model and of each variable were verified, in order to identify key indicators that will compose the analysis of applicant position in firm. Following the criteria of factor analysis techniques, the indicators that explain the maximum variance from the smallest possible number of variables were selected. The results show that the most relevant indicators for evaluating the performance of applicant position in firm are: Form of letter of application, Appearance, Academic ability, Likeability, Self-confidence, Lucidity, Honesty, Salesmanship, Experience, Drive, Ambition, Grasp, Potential, Keeness to join, Suitability. The factors Self-confidence, Ambition and Lucidity allow us to classify and compare the performance of applicant position in firm.

Keywords:Performance of Applicant Position; Factor Analysis

Introduction

An organization’s reputation, defined as a public’s affective evaluation of a firms’ name relative to other firms affects many outcomes that are directly related to organizational performance. For example, organizational reputation affects work force composition because job seekers’ initial attraction to organizations are affected by their perceptions of organizational reputation. Moreover, applicants are potential consumers for most firms. Thus, creating a positive reputation during recruitment can affect brand equity and future marketing success.

Job seekers’ reputation perceptions are important because they can affect work force composition, brand equity, and future marketing [1]. In an economy where capital is abundant, ideas are developed quickly, and people are willing to change jobs often, the most valuable organizational resource is human capital, or the talent of an organization’s workforce. However, according to a survey of over 6,000 executives from large U.S. companies, 75% of executives stated that their companies did not possess adequate human resources and that this talent shortage was hindering their ability to pursue growth opportunities. In this kind of environment, attracting “the best and the brightest” becomes a constant war for talent Fishman (1998).

Research has indicated that one major determinant of an organization’s ability to recruit new talent is organizational reputation, referring to the status of a firm’s name relative to compet ing firms. This examination proposes that a given occupation is more appealing to employment searchers when the occupation is offered by an association with a positive reputation. Thus, organizational reputation acts as a “brand,” adding value to a job beyond the attributes of the job itself (e.g., work content, pay). People’s employers are an important part of their self-concept and their social identity Ashforth & Mael (1989). Dutton, Dukerich and Harquail (1994). The connection between an organization’s reputation and a person’s identity should be particularly strong during the jobpursuit process because the act of pursuing and accepting a job highlights the volitional nature of the affiliation. Job seekers’ reputation perceptions, in turn, should affect individuals’ perceptions of job attributes and the pride that they expect from membership, which in turn influence job-pursuit intentions, minimum salary required, and memory of recruitment materials.

Applicants can apply for the position by submitting a standardized resume´ to the employer. The employer screens the standardized resume´s and subsequently selects some applicants for an initial campus interview. We operationalized the size of firms’ applicant pools by counting the number of applicants who attempted to interview with the companies (by submitting their resume´ to the firms). The dimensions of applicant quality included academic performance, work experience, and extracurricular activities. Scholarly execution comprised of detailed general review point normal and the quantity of outside dialects that the candidate recorded on the institutionalized re’sume’. Work experience was represented as the number of months of full-time work experience.

The total number of extracurricular activities listed on the re´- sume´ was used as the measure of extracurricular activities. On the other hand, firms have more immediate incentives to provide applicants with positive, rather than accurate, beliefs about organizational culture. Openly discussing unfavorable cultural attributes can turn applicants away, thereby limiting firms’ selection ratios and their ability to hire new employees, particularly considering shortages in the labor force Johnston (1992). To make their organization more attractive to applicants, managers are motivated to communicate a desirable image to applicants rather than the cultural values that operate in the organization Tedeschi & Melburg (1984).

This perspective suggests firms will overstate their positive cultural attributes and understate unfavorable attributes. Focusing on applicants’ beliefs is important, because applicants’ attraction to firms does not always lead to positive outcomes if the beliefs are misguided, and because firms have a high incentive to communicate positive rather than accurate information. This review recommended that organizations may attempt to exaggerate sought qualities to candidates, for example, chance taking, while at the same time downplaying undesired qualities, for example, rules introduction. In several cases, the relationship between company information and applicants’ culture beliefs was dramatic.

Literature

Fombrun and Shanley (1990) used the Fortune reputation data to examine several different classes of reputation determinants (e.g., profitability, advertising, charitable donations). Results revealed that firms’ reputations were predicted by both financial performance (e.g., accounting profitability, market value, and dividend yield) and, to a far lesser degree, non-financial firm attributes (e.g., media visibility, firm size, institutional ownership, and demonstrations of social concern). Mcguire et al. (1988) examined the Fortune rankings of firms’ reputations and found that stock-market returns, and accounting-based measures of financial performance were the best predictors.

The connection between an organization’s image and a person’s identity should be particularly strong during the job pursuit process, because the act of pursuing and accepting a job highlights the volitional nature of the affiliation Popovich and Wanous (1982). Accordingly, the criteria job seekers use to evaluate an organization’s reputation may be attributes related to their personal identity and needs, such as personal growth or the opportunity to work with compatible coworkers. Highhouse et al. (1999) revealed several antecedents to reputation that are very different from the factors found to affect executives’ reputation perceptions, including atmosphere, customers, and product image.

The hierarchical characteristics of kind of possession, nationality of the director, and firm recognition in authoritative depictions were controlled and their impacts were measured on firm appeal. In addition, the authors adopted a person–organization fit perspective to investigate how individual difference characteristics moderated the effects of these organizational attributes on attractiveness. Although, in general, participants were more attracted to foreign than state-owned firms and too familiar than unfamiliar firms, results provided support for the person–organization fit perspective in that the individual differences moderated the effects of the organizational attributes on firm attractiveness. Organization reputation, job and organizational attributes, and recruiter behaviors influence applicant attraction to firms. A few studies have investigated how interviews influence applicant attraction to firms, as noted by Wanous and Colella (1989).

Gary N Powell (1984) suggests that the factors which affect applicant decisions concerning jobs has focused on the effects of either job attributes or recruiting practices. The present review inspected the synchronous effect of occupation properties and selecting rehearses on the probability of employment acknowledgment by genuine employment applicant.

Brian R Dineen [2] identify the ability of firms to attract qualified job applicants is a critical component of the human resource management process. However, while a large body of research has examined the relationship between firm recruitment practices and applicant pool attributes, very little research has investigated what factors are associated with organizational decision makers’ utilization of specific recruitment tactics. Richard T Cobe (2004) commented that the use of organizational web sites for recruitment has become increasingly common. Despite their widespread growth, however, little is known about how these web sites influence recruitment outcomes [3-5].

Paul W Mulvey (2000) concentrate on the convictions that candidates create about organizational culture during the anticipatory stage of socialization. Work candidates recommended that an association utilized item and organization data to urge candidates to hold good, as opposed to precise, culture convictions. Pay is a vital employment quality Jurgensen (1978) and affects work allure and consequent occupation decision choices Rynes (1987). Research on the relationship between compensation systems also, job attractiveness regularly has inspected the impacts of pay level Barber (1991).

Daniel B Turban and Thomas L Keon (1993) examine an interactionist perspective to investigate how the personality characteristics of selfesteem and need for achievement moderated the influences of organizational characteristics on individuals’ attraction to firms. Subjects read an organization description that manipulated reward structure, centralization, organization size, and geographical dispersion of plants and offices and indicated their attraction to the organization.

Research Methodology

The data were taken from the Kendall M (1975) Multivariate analysis. Griffin, London corresponding to 245 Applicants for position in firm who have been judged on 15 variables. In the study following empirical Multivariate technique is used to identify the applicant position in firm by using Factor Analysis.

Results and Discussion

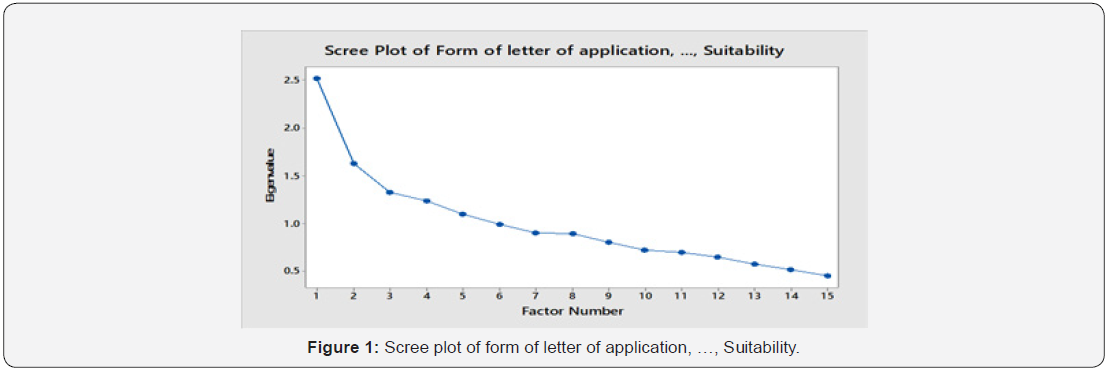

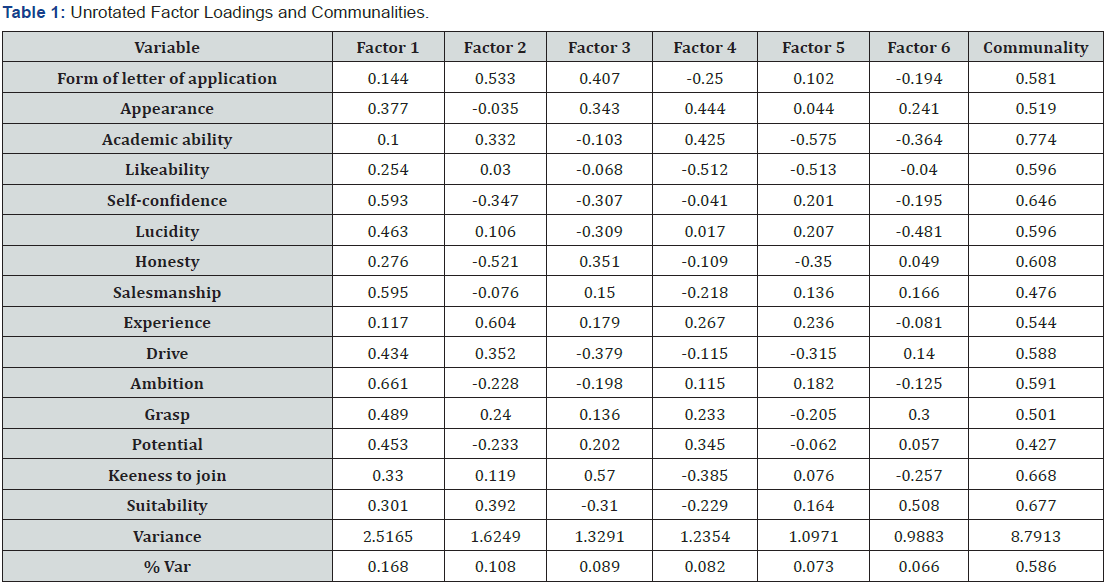

As Shown in (Table 1) Unrotated factor loadings and communalities, the first five factors have variances (eigenvalues) that are greater than 1. The eigenvalues change less markedly when more than 6 factors are used. Therefore, 6 factors appear to explain most of the variability in the data. The percentage of variability explained by factor 1 is 0.168 or 16.8%. The percentage of variability explained by Factor 5 is 0.073 or 7.3%. The scree plot shows that the first five factors account for most of the total variability in data (given by the eigenvalues). The remaining factors account for a very small proportion of the variability (close to zero) and are likely unimportant (Figure 1) [6-8].

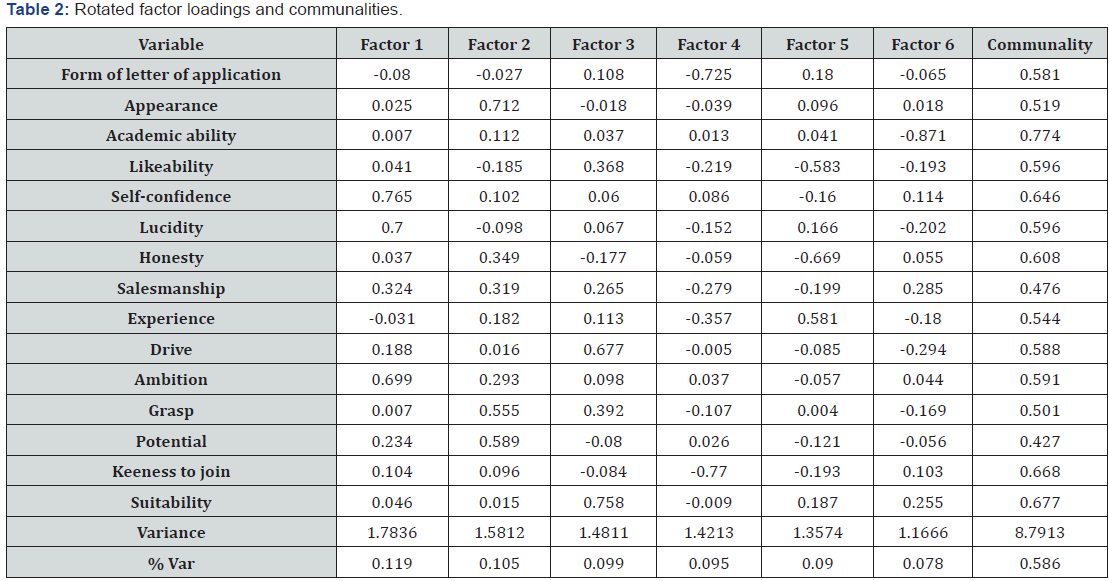

As shown in (Table 2) Rotated factor loadings and communalities, varimax rotation was performed on the data. Using the rotated factor loadings. Self-Confidence (0.765) and Ambition (0.699) have large positive loadings on factor 1, so this factor describes that self-confidence and ambition for growth in the company. Appearance (0.712) have large positive loadings on factor 2, so this factor describes that Appearance for growth in the company. Suitability (0.758) have large positive loadings on factor 3, so this factor describes that Suitability for growth in the company. All six factors explain 0.586 or 5.86% of the variation in the data [9,10].

Conclusion

In this study, we find out the factor analysis on evaluating the applicant’s position in firm data. In this study, multivariate data were recorded from the Kendall M (1975) Multivariate analysis. Griffin, London. Data consists of 245 observations and 15 variables. For this purpose, the Multivariate data technique “Factor Analysis” is used. All data analysis was done on Minitab16. The factor analysis was conducted on 15 different variables of applicant’s position in firm then 6 factors were selected from the selected variable all other variables are well explained by the chosen factors explain most of the variation (0.58.6 or 58.6%) [11].

For the applicants a position in firm data, 6 factors were extracted from the 15 variables. All variables are well represented by the 6 chosen factors, given that the corresponding communalities are generally high. The percent of the total variability explained by the factors does not change with rotation and the communalities remain the same. But, after rotation, the factors are more evenly balanced in the percent of variability that they account for (compare the %Var rows from the unrotated and rotated output).

We conclude that the percent of the total variability explained by the factors does not change with rotation and the communalities remain the same. But, after rotation, the factors are more evenly balanced in the percent of variability that they account for (compare the % Var rows from the unrotated and rotated output).

References

- Gatewood, Feild HS, Barrick M (2015) Human resource selection. Nelson Education.

- Brian A Jacob, Jonah E Rockoff, Eric S Taylor, Benjamin Lindy, Rachel Rosen (2018) Teacher applicant hiring and teacher performance: Evidence from DC public schools. Journal of Public Economics 166: 81-97.

- Backhaus KB (2016) Organizational identity, corporate social performance and corporate reputation: Their roles in creating organizational attractiveness. In Corporate Reputation pp. 127-146.

- Hung CL (2017) Social networks, technology ties, and gatekeeper functionality: Implications for the performance management of R&D projects. Research Policy 46(1): 305-315.

- Swaney, A (2017) Employee selection practices and performance pay. Available at SSRN 2481074.

- Greer CR, Carr JC, Hipp (2016) Strategic staffing and small‐firm performance. Human resource management 55(4): 741-764.

- Cortázar JC, Fuenzalida, Lafuente M (2016) Merit-based selection of public managers: Better public sector performance. An exploratory study (Technical Note Nº IDB-TN-1054). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. USA.

- Quadlin N (2018) The mark of a woman’s record: Gender and academic performance in hiring. American Sociological Review 83(2) 331-360.

- Cocchiara FK, BellMP, Casper (2016) Sounding “different”: The role of sociolinguistic cues in evaluating job candidates. Human Resource Management 55(3): 463-477.

- Bernard Arogyaswamy (2017) Social entrepreneurship performance measurement: A time-based organizing framework. Business Horizons 60(5): 603-611.

- Dylan Minor, Nicola Persico, Deborah M Weiss (2018) Criminal background and job performance. IZA Journal of Labor Policy 7(1): 8.