The Digitization of the Economy and the New Dynamics of Industrial Firms

Paul Rosele Chim1* and Bertrand Panhuys2

1Teacher-Researcher, University of Guyane, Beta Minea EA 7485

2Associate Researcher, University of Guyane, Beta Minea EA 7485

Submission: October 10, 2018;Published: December 04, 2018

*Corresponding author: Paul Rosele Chim, HDR Paris 1-Pantheon Sorbonne, Teacher-Researcher, University of Guyane

How to cite this article: Paul Rosele Chim, Bertrand Panhuys. The Digitization of the Economy and the New Dynamics of Industrial Firms. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2018; 2(3): 555589. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2018.02.555589

Abstract

The digital revolution imposes new modes of consumption and production. Internet, networks, big data, information flows, connected objects, applied services: the whole ecosystem is modified. Beyond the major socio-economic issues, there are upheavals in geopolitical equilibrium and the emergence of a new economic order, despite low levels of growth. Leading firms, such as GAFAM, are adopting monopolistics strategies that threaten the major market equilibria and force us to question the regulatory instruments.

Keywords: Digitization; Innovation; Organization; Model; Industry; Firms; Performance; Growth; Globalization; Local Development

Introduction

Before the massive spread of Internet in the 1990s, the media markets were compartmentalized. The integration of large groups was mainly vertical, thanks to deregulation initiated in the field of television (ABC, Disney, AOL-Time Warner). This structuring has been completely modified with the arrival of digital technologies. Historical groups in this field are gradually entering into competition with others from related fields such as networks, operating systems, computer equipments, Internet platforms, etc. This is the phenomenon of verticalization of the value chain » often emphasized by Lombard [1,2]. New digital giants are born: the GAFA or GAFAM Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft.

Henceforth, the goal is to make a coherent ecosystem mastering at the same time, upstream the constraints related to the setting up of the networks and supports carrying the information (containers) and, downstream the expectations of the final users in terms of both basic services and more sophisticated digital solutions (contents). The market structure is oligopolistic. Therefore, competition occurs in an environment where both competitors and partners coexist. Indeed, the actors are in coopetition as indicated by Rosele Chim [3-8] examining the classical theories on competition and those on cooperation. Thus, they compete on certain markets or segments and cooperate on others, each one seeking to satisfy a targeted demand according to his level of specialization or his core business.

The digital revolution is in processing and imposes new modes of consumption and new business relationships. Several questions then arise. What are the effects of training on organizational models, distribution methods, the distribution of employment, which finally question labor law and social protection? To what extent can businesses reinvent themselves to adapt to these significant changes? How can individuals and society be able to cope with the rise of the vast process of disintermediation that is taking place on the targeted markets (the phenomenon of uberization of the economy)? All these questions are essential as this process is altering our vision of the world and is modifying our practices.

Our Study Presents Three Highlights that Focus on These Issues

a. firstly, the digitization as a factor of a new industrial economic order;

b. secondly, the new power of firms thanks to the multiplier networks of the current revolution;

c. finally, the risks of imbalance of the system and possible regulation instruments.

The Digitization for a New Economic Order

New Information and Communication Technologies (NICTs) have often given the feeling of the appearance of « New Economy » compared to « Old Economy ». The configurations outlined by the technological alliances of firms propelled the industrialized countries into the emergence of a long cycle of growth with strong disruptions. Economic renewal puts traditional analysis to the test. Perceptions are varied between electronic economy, digital economy and industry 4.0. The field covered by digital economy is very distinctive.

Approach and Framework of Analysis

Let us choose the following approach: all economic and social activities using internet networks, connected objects, electronic sensors that mobilize aggregation of « big data » for the treatment of information of their entire value chain from the producer to the final customer. Today modern firms must first create desires in the consumer’s life in order to be able to impose themselves as a producer guaranteeing their satisfaction. In Galbraith [9] revised sequence », in contrast to classical industry where offer for goods and services must satisfy demand of consumers, it is the individual with unlimited needs who serves the expansion of economic structures.

Would demand dictate its law to offer? Maybe indirectly, unbeknownst to consumers. Apple, like other digital giants, did it not captivate its customers to sell them the created applications and services? Indeed, the dynamics of the entire ecosystem is based on the « manufacture » of a being in the grip of the need to consume. The latter is the means likely to ensure the growth for growth that presides over the decisions of the technostructure. As technology and power of computation are no longer limiting factors, firms seek to collect considerable data, which are then aggregated, processed, stored. This information is useful for controlling the production process (producers) and better market expectations (customers).

The changes brought about by digital technology compel world-class firms, as well as smaller firms, to permanent adaptations, both technologically and organizationally because of the change in uses, information and culture. This economy integrates new networks that, beyond new activities (specific services, business creation), lead to better performance (energy, industrial, environmental) through lean management and more « smart » processes. Here the notion of supply chain appears essential to the extent that manufacturers seek to pool their resources, to create synergies, particularly by developing common supply platforms to gain advantage over competitors.

How do these mutations take place in the countries? Take the case of France and Germany. According to the Economic Analysis Council (2015), France can rely on the strengths that constitute a significant demand, the flexibility allowed by the status of the auto-entrepreneur, an authority of experienced competition and a proactive policy of access to data. On the other hand, it is lagging on the supply side. The main reason for this situation is overly rigid sectoral regulations and a poorly adapted financing structure to minimize this gap, even to conquer a leadership position, France must notably be tolerant with its sectoral regulations, in order to boost the experimentation of new business models and promote healthy competition.

Moreover, Germany has launched a major project to digitize its industry since the end of 2012 in order to maintain its competitiveness. The challenge for businesses is to move from today’s centralized management of their production to decentralized management. In the core of factories of the future, faster, less energy efficient, more flexible, we find Internet and a new discipline: cyberphysics. In industry 4.0, there is a generalization of embedded systems, softwares, flow and data management software. They must allow a better communication between the machines and a better interactivity man-machine.

The observation thus established allows to better identify the more serious issues, especially for the industry that is at the heart of these changes both internally (optimization of organizational processes, adaptation or renewal of the production tool) and externally (changes in regulations, customer satisfaction).

Study of Socio-Economic Issues

On one hand, the digitization appears as a simple evolution because of its very weak ripple effects on all sectors of economic activity and on the employment, even if we can recognize its role of catalyst in the third industrial revolution. The machine in some jobs replaces man but, for all that, there is no increase in production yields due to technical progress as in the 20th century. Gordon (2016) believes that this revolution is not able to have impacts with the same intensity as the two previous ones: « washing machine contributed more to emancipation and quality of life than smartphone ». « Elevator and refrigerator did more than Internet ». It only concerns communication and entertainment, at most 7% of GDP. Even the big data, used in marketing and technicalcommercial services, would not have a significant scope. The same is true for employment effects. Robert Gordon recalls that the United States is today in a situation of almost full employment which challenges us as to the reality of the shocks of digitization of the economy.

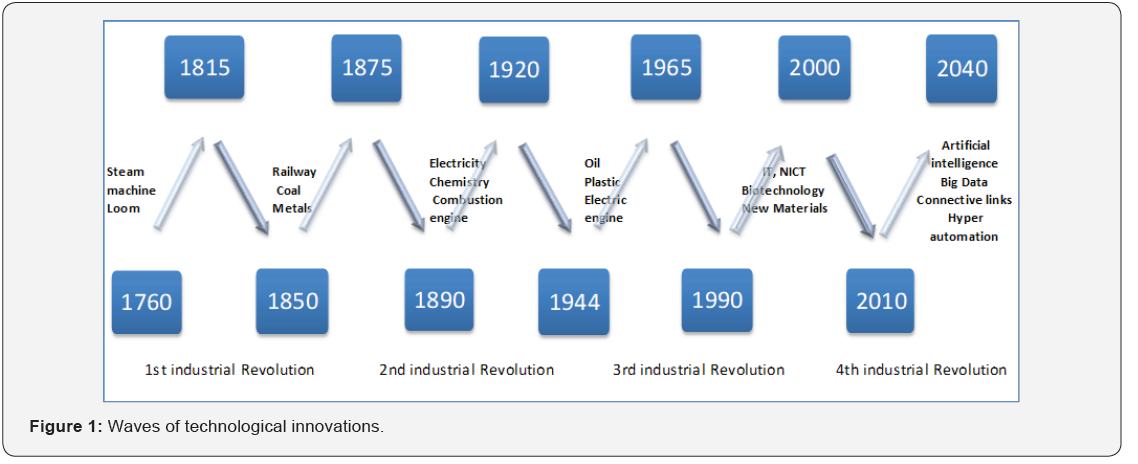

On other hand, it is believed that the world is truly entering a new technological era and prefers to highlight the many virtuous innovations. According to Joseph Alois SCHUMPETER, successive shocks or waves of upswings and downswings have impacted society and punctuated its transformations, since the birth of industrial capitalism in the nineteenth century. Entrepreneur or innovator is essential in Schumpeter analysis of the process of development which is dynamic and discontinuous. Innovations in one field of activities can induce other innovations in related fields (Figure 1).

The Following Indicators Also Show that the Digital Revolution is in Processing

a. Increase in productivity gains, after a sharp slowdown at the end of the « Thirty Glorious years » until the mid-1990s;

b. Creation of productivity gains in a very singular way in services whose share exceeds 75% in the economic sectors;

c. Considering the energy constraint and the availability of raw materials that has changed the perception of consumption and renewal of resources;

d. Measure’s evolution of wealth’s level: from GDP to the HDI. Wealth and industrial power could not be measured only by business value added, social inequality or poverty level, but also since the citizens’ willingness to build a fairer and healthier society (system of health education, unemployment insurance). In the sense of Amartya SEN (1990), the digital does not escape these choices of access to knowledge and leisure for all people with the development of more and more « free » applied services;

e. Need or obligation of technological breakthrough for businesses due to the preeminence of advanced computing (artificial intelligence , exploitation of big data, exploitation of cloud), also the proliferation of connected objects (link between the physical object and the digital with the problems related to the recovery of data as well as their processing and storage), and then the democratization of advanced robotics (cobots, collaborative robots, autonomous machines).

Similarly, the evolution of human-machine relations challenges us: do need and use justify production when machine makes easier access to information and decision-making? Permanently, the use of network opens new perspectives to Internet users and implicitly changes their behavior. Internet is the main model. Originally mass media, nowadays social space where communication by text and image is instant and unlimited, consequently it becomes a social network (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and more).

Consumer’s behavior as firm’s behavior has evolved in the same way. All branches of industry have become those of the NICT industries [5]. These last ones seek to better know the customer to better satisfy him. Hence the demand is more volatile, unpredictable, and the success of firms no longer depends on mass production and the search for efficiency under cost constraint through economies of scale, but the speed and flexibility of the response to market demands with more personalized and higher quality products. Industry should gain in competitiveness thanks to new technologies (connected machines, additive manufacturing, process digitization, cyber-production system).

Objects that are more and more connected are not worth their own value, but rather associated services, most often in online space. The challenge for businesses is to find even smarter processes to adapt. In factories, performance management is measured by the flexibility of production, the traceability of information in the production process and energy savings. Contemporary economic philosophy [10,11] reminds us that: we are currently experiencing a period of immense change, comparable to the end of the Roman Empire or the Renaissance. Our Western societies have already experienced two great revolutions: the transition from oral to written, then from written to print. The third is the transition from print to new technologies, equally important. This change involves major upheavals at all levels.

Upheavals and Emergence of a New Model

Technology is a factor of rupture, destabilization, change. The importance of geopolitical upheavals or economic stakes is in line with the strong and sustained growth of firms in the most developed countries. Indeed, these large organizations stand out in the world market by their financial weight, the multiplicity of defended interests, the extent of production and distribution sites and their spheres of influence, which are beyond the legal, political and economic power of the host States.

In 2016, the technology sector outperforms the financial sector as indicated by the PwC annual ranking of the world top 100 market capitalizations. GAFAM are in the first place among American firms that remain globally the most dynamic and the best valued in the world: they represent 54% of the top 100 firms, ahead of those from China and Hong Kong (11%), the United Kingdom (7%), Germany (5%), France (4%) or Japan (4%). Their level of market capitalization has more than doubled since 2009 reaching $ 16,245 billion in 2015 and $ 15,577 billion in 2016. This figure is comparable to US GDP ($ 18,624 billion in 2016).

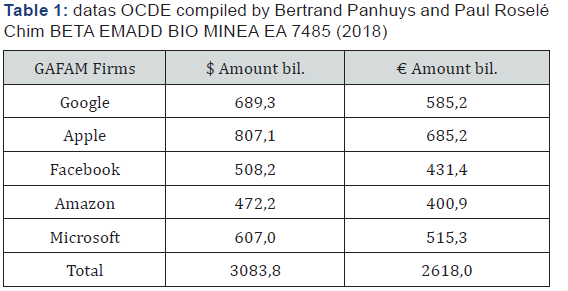

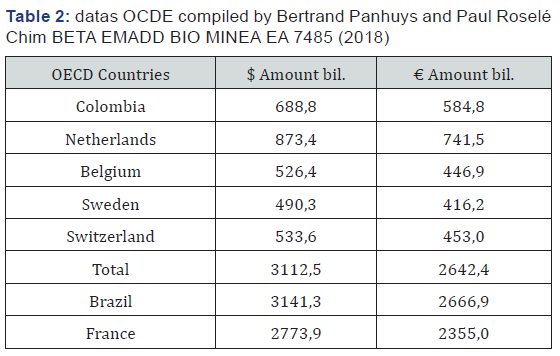

More specifically about the weight and influence GAFAM, we can make the following comparison between their market capitalization and the GDP of certain countries: Note that the stock market valuation of Apple is slightly lower than the GDP of the Netherlands, that of Microsoft is comparable to the GDP of Colombia or exceeds that of Switzerland. Similarly, the financial weight of GAFAM exceeds the wealth created by France and is at the same level as that of an emerging country such as Brazil (which produces a wealth superior to France of nearly 15%) (Tables 1 & 2).

Moreover, in the field of the Internet, we note that American and Chinese firms also exercise significant power: The United States account for 72% of the top 50 world sites against 16% for China. The open path in this field and in those directly associated with it (networks, IT, multimedia, etc.) suggests the emergence of a bipolar world without the European Union [12]. By observing the dynamics of European firms on highly technological and strategic markets, we can notice the strong skills required in digital technology. For example, in aeronautics (Airbus, Safran, Thalès, Rolls Royce, Zodiac) or space (launchers, satellites) with the operational implementation of the future Galileo geolocation system competing with the American GPS, the multipolarite could be preserved. European Union thus strengthens its position in the global « representative » of Internet governance by influencing political orientations and industrial strategies to better support European firms in the digital transition.

Beyond the geopolitical stakes, a new model is setting up. Firms now need « real time » signals from the evolution of the market. They set up ad hoc processes that can collect and interpret these information flows. The goal is not to miss the next technical « disruption » a total break with the previous phase as it generates radical changes. Disruptive innovation is a breakthrough innovation, as opposed to incremental innovation, which merely optimizes the existing [13]. Thus, the firms potentially in commercial competition can form a network to work in partnership, in order to increase the creation opportunities in adequation with the expectations of the market. They also gain in performance by using their internal resources and relying on external resources in the fields of competence dedicated to each provider. This is the rule of coopetition according to Rosele Chim [8].

By revolutionizing organizational models and modes of distribution, digital economy first imposes new ways of consuming characterized by the « dematerialization » of consumer products. The digital revolution disrupts certain business models in many economic areas or traditional media [5,8]. It bypasses service providers or formerly established intermediaries. As such, it initiates a vast process of « disintermediation » which favors the mediation of the new giants of the Net on the concerned markets. This is the phenomenon of uberization of the economy according to Bassoni and Joux [14,15].

The contemporary period is marked by an economic model of products and services permanently free. This is a real cultural and sociological revolution for users who no longer must pay to consume their information assets: online newspapers and music, radio shows in podcasts, TV, videos, movies in streaming. They can now go on platforms to perform their transactions (Amazon), to access applications (windows, iTunes) or to perform their research or information (Google, traditional online media sites). Greffe and Sonnac [16] consider that these platforms allow, on one hand, to make quantitative and qualitative audiences available to advertisers, and on other hand, to push for the development of specific business models and dynamics. Here the success consists in the ability of each to structure its users in communities offer them services and tools that will facilitate their virtual social interactions.

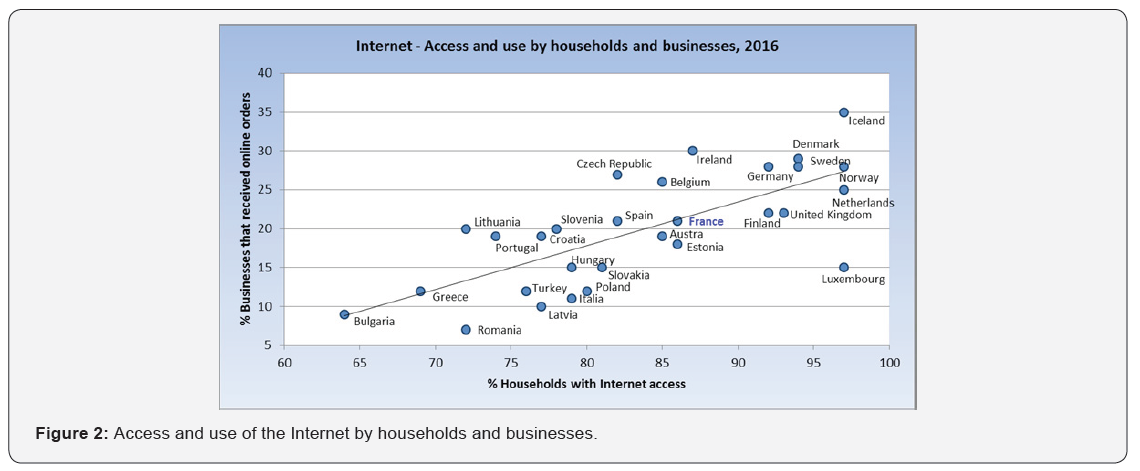

Countries also can take advantage of these technological advances by focusing on household equipment and encouraging businesses to invest in Research and Development to make full use of the new offered capabilities (e-commerce, client and supplier data processing software, secure transactions) (Figure 2). The chart above illustrates the digital divide between European countries, with some not giving consumers or businesses the opportunity to use new technologies to facilitate adaptation to new models of trade, transactions and management. It is also noted that it is mainly the more affluent countries of the North which have fully changed in this new economy. As an example, we can cite the success of the Israeli industrial model through its role as active investor, its directive steering and a strong tax incentive [17]. In fact, for nearly 15 years, the government has successfully launched a $ 100 million venture capital fund to help create startups and high-tech, high value-added projects.

Israel has become the first country in the world with the highest ratio of R&D expenditures to GDP, far ahead of the United States, the OECD countries and France. Israel has 4.3% in 2010, against 2.8%, 2.3% and 2.2% for other countries respectively. Finally, the consumption habits of citizens have been considerably modified, demanding a strong and rapid adaptation of businesses as well as their production process. Hence the emergence of a new economic model where firms will develop another form of power.

The New Power of Firms

The movie and audiovisual programs industry in the United States as well as in Europe, in addition to France, constitute the illustrative field of firms constantly changing the strategic alliances [18,19].

Business Strategy and Power of Market

The long history of industrial crises in the field of movies and television highlights technical and technological transformations that have triggered the disruption of NICTs [3,6]. We observed in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s a vast movement of concentration in the world of the media. Behind the American Majors, like the networks of Europe, the dynamics of the technological clusters is intense. Controlling products and markets presents several explanatory factors: evolution of technologies including digitization and compression of signals; d e r e g u l a t i o n which leads to the end of natural monopolies for the exploitation of networks and the provision of telecommunications services; transformation of the competitive environment that will drive players to massively diversify their activities towards the multimedia markets following the collapse of the traditional sectors of the electronics industry; current situation due to the growing interest of consumers for activities related to multimedia and which require firms to adapt.

In fact, the new competitors appear from very different fields: network infrastructures, IT, audiovisual, publishing, distribution. These firms that emerge seek to control programs (contents) and distribution networks (containers) as explained Guillou and Mouline [20,21]. The phenomenon of globalization, the expansion of cultural and informational consumption, the power of the market and the maintenance of the content industries, has spread to the cultural, informational and communicational industries outside the world. Major firms have emerged by mastering the tools and new uses of the web. As an illustration, in the field of music, the popularity of iTunes, Apple Music, YouTube, YouTube Music remind traditional firms how much they are dependent on the decisions of the giants of the Net, which threatens again the recorded music market.

The successes of these new world leaders come from their ability to force users to use their application or materials. The work of Kelly, Shapiro and Varian [22,23] shows that the consumer will find himself in a system quite different from that of traditional neo-classical economics. Its purchasing autonomy is subject to sometimes strong constraints. Indeed, the user of certain technologies can be « locked » without being able to easily change technology.

Like most global markets, Internet has an oligopolistic structure with businesses that, because of their ability to impose standards, tend towards a dominant or even hegemonic position. That allows to highlight three factors: drop in the costs of technology, according to the MOORE law, permanent innovation and intelligence. The cost of production of a smartphone is low in view of the value of the components necessary for its manufacture, in view also of the number of users as well as the applications and operating systems developed and updated regularly in line. In this context, we can understand that the movements of concentration continued with the development of Internet and associated applications. Two main and indissociable reasons can be invoked: on the one hand, the added-value chain linked to content and the resulting wealth creation capabilities; on the other hand, the structuring of the production of the containers and the search for management optimization of trade flows and logistics necessary for the distribution of final goods.

In fact, overall satisfaction depends both on the quality of the products and services adapted to the expectations of consumers and the organization of the market. For these leading firms, purchasing has become a source of productivity. Because buyers, faced with the multiplicity of information channels and orders, want to see more complementarity between tools and better harmonization of data collected by the company. Thus, the supply function has evolved while allowing to provide innovative and quality products, and avoiding stockouts, elements both costly for the company and negative in terms of image and notoriety. It is from now on the whole chain of value that the company considers in the evaluation of its performance. It adapts in an almost iterative way, according to the cycles of production and the evolution of the competitive environment, all its processes for the realization of the fixed objectives.

In this context, the control of costs or delays as well as the control of the quality or the reliability of the final production remain; but other indicators are also used to measure the success of the corporate strategy: customer loyalty, improvement in economic performance (sales, operating margin) or financial performance (profit per share), promotion of image or brand, innovation (R&D budget, collaboration with research laboratories, patents pending), internal and external growth prospects for the company (unprofitable activities outsourcing, key skills current or future strengthening by training or recruiting the necessary talents, positioning on international markets).

The situation we have just described makes it possible to better understand the market power of these new players who, taking advantage of the high expectations of consumers, manage to make them captive. Nevertheless, other elements that did not exist in the previous revolution must be considered to ensure their strategic power: networks and empowerment.

The Era of Networking and Empowerment

Through networks, firms can adopt strategies to diversify their activities. This allows, on the one hand, to erect barriers to entry against potential competitors. According to Stigler [24], a barrier to entry is a cost of production that must be charged by a firm wishing to enter a market, without those already in place having to do it. This offers the opportunity, on the other hand, to set up an investment policy whose profitability is more secure. In fact, the risk of loss is reduced because of the holding of a larger products portfolio and profit prospects discounted on other markets. Megafirms correspond to a global market and millions of captive users.

For the third type of firms after the multinationals, the most important is not so much the gain in market shares as the network constituted by the number of users who fuel the need for development of closed mobile applications to the Internet service. Competition is no longer at the level of the operating systems but more platforms with data become permanent: innovation, alliances, searching for external growth. Facebook confirms it; according to manager Mark Zuckerberg, performance goes through a more open and connected system.

Thanks to the increased use of digital channels and common platforms for data exchange and processing, B2B is constantly growing. Similarly, on the consumer side, the more widespread use of Internet strongly influences exchanges between individuals (online sales and purchases). « GAFAM deal with the same users but with its own assets: mobile terminal, research browser, advertising browser, cloud platform, community of developers » according to Bourdin [12].

Nevertheless, several characteristics of these markets on which these large firms are positioned, make it possible to measure well the difficulties to maintain a stability of networks and a continuous growth: First, they are hyper fragmented and heterogeneous. Then the situations of dominant positions are very quickly jostled because of the pressure of new entrants or substitutable products. Lastly, product cycles are very short and innovation processes are constantly improving. It is the result of the search for creativity and permanent innovation that ultimately leads to the development of new services and new markets. All this poses significant risks to the market equilibrium and pushes to question the means of regulation.

The Risks of Imbalance and the Search for Regulation

The 2007 crisis demonstrated the complexity of business relationships, the inability to master information flows or to predict the onset of a collapse of a growth and confidence-based system. With the advent of digital technology, we can wonder, beyond its beneficial effects on global economy, on its capacity to create growth through technical progress and to ensure an increase in social well-being. Finally, the combination of financialization, digitization and globalization would constitute all the explanatory factors for the deregulation of the system, with each element allowing the other to increase its intensity and its propagation.

The Relation Between Technical Progress and Growth

Many firms, like the media groups or giants of the Net, have gone through economic and organizational crises, forcing them to reinvent themselves to survive Bassoni and Joux [15]. Businesses must constantly adapt their production model to market developments. This external environment can be at the same time very close (local market) or very distant (global market) but impose very strong constraints to be considered in the development strategy. According to Bassoni and Liautard [14], the territories bear the stigma of the « creative destruction » that Ja Schumpeter [25] explained. They are, over time, the theaters where two concomitant and inextricably linked processes take place: that of the decline of traditional activities and the rise of new activities ».

This trend is well underway and affects all sectors of economy. But a fundamental question arises: will this digital revolution increase the productive capacity or, on the contrary, as Cohen [26] asserts, that it will not bring anything comparable to the technological revolutions related to the invention of electricity and combustion engine? The report of slow economic growth observed for thirty years in the United States, with a median income that no longer progresses despite the arrival of digital technology, would rather support the second thesis. The firm no longer creates enough added value for the employment of additional staff and for training effects in other economic sectors since it outsources activities to subcontractors in a massive way.

In addition, compared to previous periods, the contribution of technological progress generates insecurity by replacing jobs with robots, with automation chains, with intelligent processes. 50% of jobs would be threatened by the development of digitization. It is the middle classes, the banks, the insurance businesses and the administrations, which seem the most exposed by this evolution of the employment because of the increase, on the one hand, of the need of labor poorly qualified to carry out basic tasks and on the other hand, of important resources released by and for those who are behind this digital transformation. In the United States, 1% of the richest people have seen their share in the GDP increase of 15 points in thirty years.

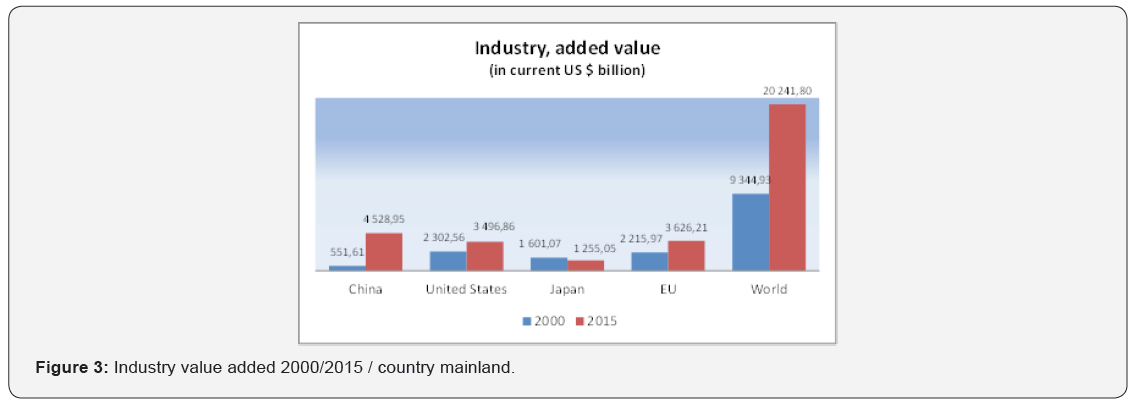

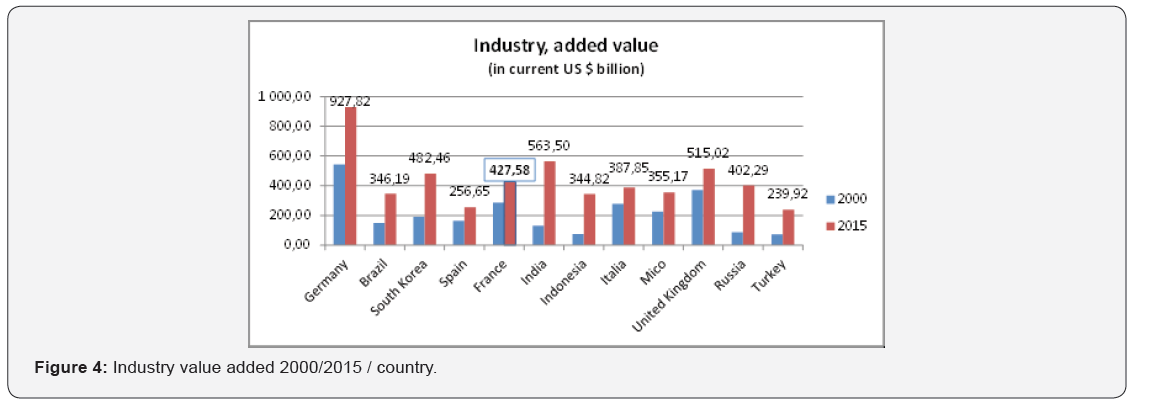

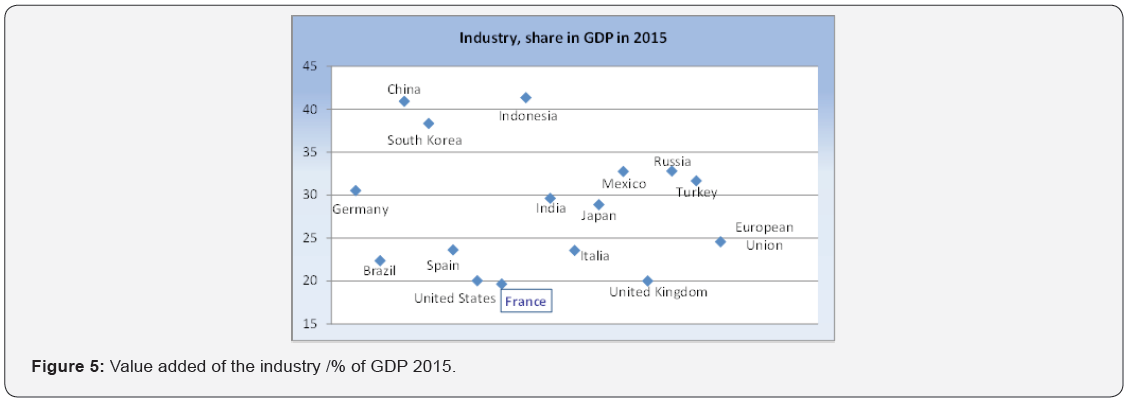

The challenge for the future is no longer to increase the productivity of men at work (lower than in the 20th century), robots and computers replacing them, but to redistribute the profits and above all, to raise the level of well-being of all (education, health, eco-citizenship, eco-transportation). The economic sphere is turned to producing not goods but applications that provide users with free information. As a result, what is of value it is what escaped this free, it is the positional goods: where I live, or I send my children to school, can I be healed in good conditions [26]. In this context, France has made the implicit choice for three decades of an economy without industry. In the charts below, we can observe the place that France occupies among the industrialized countries in the world and in Europe (Figure 3-5).

We can admit that between 2000 and 2015, the process of industrialization concerns emerging countries and especially China, which alone exceeds $ 4 500 billion in value added. The BRIC group has recorded very strong growth, unlike European countries which have not developed their production tools. South Korea, in full industrial transformation, has managed in 15 years to exceed the value added of France, Russia, Mexico or Indonesia. This dynamic is explained by the importance of the share that some countries devote to industry in GDP: over 35% in China, Indonesia or South Korea, 30% in Germany, Mexico or Russia, France being below 20%, like that of the United States or the United Kingdom.

In view of these elements and the trends that emerge, several questions arise. The digital revolution and the challenges it poses are not an opportunity for the implementation of a process of reindustrialization and revitalization of businesses turning to more competitiveness. Will this revolution have the capacity to relocate industrial activity that has disappeared to the extent that factories, which have become more flexible and automated, have production costs that are almost « insensitive » to the cost of labor?

Indeed, the previous revolution had put more on an increase of the volumes to justify the economic investment and to increase the production, the size and the costs of return of the businesses. Today, the theoretical growth factors are based, at constant product volumes, on the reduction of capital consumption and a return on investment from higher capital employed. Nevertheless, thanks to 2008 crisis, the direct effects of digitization have been significantly accentuated. It is the rise of unemployment, precarious jobs, the decline in average wages, the growing deficit of foreign trade, the obstacles to growth, the devitalization of territories, the increased vulnerability of society. The sustainable development is considered in some extent by a production turned to employment. Indeed, the industry includes a mode of distribution of wealth through the wage system, while the NICT model does without it by accentuating the unemployment of performance and competence.

Six Orientations are Advocated

a. support creativity and human development through the modernization of the education system, valuing the imagination and taking risks;

b. develop economy based on quality and provided services;

c. renew the energy model and master consumption for all and sustainably;

d. initiate a « big bang » of territories (mobilizing and structuring projects);

e. put finance at the service of growth;

f. strengthen global influence capacity by improving the competitiveness of firms and by acting within Europe to rebalance competition between emerging countries and the first industrialized countries.

g. These guidelines challenge the sustainability of development and governance: govern differently to produce otherwise.

GAFAM and other high-tech companies have accompanied digital change. It is a question of working in a transversal way in collaboration with the actors of the market to advance the scientific research, the development, the applications at the service of the product. The goal is to move towards some form of social welfare of individuals.

Global Competition, Strategic Coopetition and Risks of Collusion

Beyond the problems related to competition, there is the question of the sharing of added value between the different actors: service intermediaries (Facebook, Google), incumbent operators (Orange, British Telecom), network and terminal equipment manufacturers (Alcatel Lucent, Dassault System), content producers (Disney, AOL-Time Warner, Newscorp). The emergence of GAFAM and their mega-power was built through major breakthroughs: hardware (Apple), search (Google), e-commerce (Amazon), social (Facebook). Industry 4.0 offers new perspectives of digital applications for the benefit of citizens, customized products, needs and specific markets.

The search for an optimum of satisfaction goes through the development of business networks, common platforms of exchanges, partnerships between the academic and scientific world and that of companies, multiple collaborations in order to answer the economic and societal problems. The stakes are up to the challenges that we perceive in the 7 industry paradigms 4.0 described by Blanchet [27]: management of the complexity induced by digitization allowing the customization of products ; industrial relocation near final markets with high automation production processes ; dynamic and more efficient supply chain (lean); end of the product-service divide and supplier-customer reconciliation thanks to the data collected and which allow to improve the quality of service and to optimize the life cycle; end of the logic of an economy of scale, the new technologies implemented mobilizing the physical asset more and allowing the passage from a « push » logic (to manufacture to store) to a « pull » logic (to make on command); end of Taylorism with learning organizations and increased reality technologies (increased monitoring, remote work, tele maintenance, remote factory inspection). more energyefficient industry (circular economy), better integrated in its territory of implantation (CSR approach) and more attractive [28- 31].

The coopetition practiced by most big firms that provides a balance of power should gradually fade in favor of more intense competition due to the increased development of networks, clouds and big data. In this context, how to ensure balanced competition for the benefit of consumers? The arrests, interrogations and hearings in front of the institutions in the United States and the recent trials in Europe against the GAFAM show the limits of the digital economy where the influence of firms and markets exceeds the power of States. Which regulatory instruments to implement?

Regulation Instruments

According to neo-classical economics, and particularly the school of industrial organization, it is necessary to think of the necessity of reinventing a more socially model of growth just by integrating the future generations, more economical and more durable. This seems conceivable in the evolution of economic thinking, of industrial analysis, which is gradually considering the human approach of the aleas of the conditions against growth. It places greater emphasis on the training of precarious populations, namely unemployed and unskilled, on the emergence of new skills, on social innovation and on the optimization of available resources in the light of the consumption [32-35].

Another vision encourages us to put forward rather the voluntarist strategy aiming at the search for the competitivity of the companies at the local scale of the territories to integrate in the model of regulation all the societal evolutions. Thus, countries and regions can exist in terms of industrial weight and have influence in terms of geopolitical weight at the global level. Economic poles in globalism would favor the emergence of high value-added technologies sold in the world. Hence the questions about the nature of the businesses in the future, their organization, their production, their market and their process of survival [36-38].

The dynamics of liberalization is at the heart of digital economy that cannot seek to control markets and firms whose field of action is supra-national. There appears to be a temptation in the global market between the return to protectionism on one side and the intensification of liberalization on the other side. Indeed, there are counter-powers to the large influence of digital economy: the consumer is first, versatile and communicating globally via networks and potentially sensitive to the image of the firm in case of repeated and notorious; the competition is then stronger and focused on innovation, structural and partnership organization; the regulator is finally, on the lookout for any risk of technical, legal or financial imbalance to guarantee an optimum of satisfaction to the consumers and more broadly to the society [39-42]. This is a form of declining general equilibrium with the Paretian optimum since more CSR logic is considered with respect to the external environment. And we find corroborated the principle of the research of the balance between the industrial regulation and the innovation [43,44].

Conclusion

The digital revolution has effects on all areas of society. Consumption habits have been modified, pushing companies to adapt their mode of production. GAFAM and new types of companies from the Internet and the high-tech sectors stand out thanks to their own identity and their capacity for innovation.

The power and influence of these organizations is significant in achieving the balance of fragmented, heterogeneous and volatile markets due to competitive pressures and ongoing innovations. Liberalization is faced to protectionist temptations. The context challenges the rationalization of organizational models and productive activities, the mode of job destruction, societal involvement and the method of profit compilation. States are grappling with the model of digital economy and the dynamics of a new type of industrial organization through the protection of citizens (Google), the avoidance of instrumentation (Facebook), the ecosystem predation (Amazon), the tax avoidance (Apple, Google, Amazon, Airbnb). Adaptations are long term. The changes are important.

References

- Lombard D (2008) Le village numérique mondial, (Edn), Jacob, Paris, France.

- Lombard D (2011) L’irrésistible ascension du numérique, Edition O. Jacob, Paris, France.

- Rosele Chim P (1989) L’industrie cinématographique française à l’ère de la crise mondiale, Thèse de Doctorat, spécialité Stratégie et Développement Industrielle, Université de Paris X-Nanterre, Paris, France.

- Rosele Chim P (1999) Strategic alliances on technological network activities: the case of European multimedia, International Conference, TEAM-CNRS, CESSEFI, Ministère de l’Economie des Finances et de l’Industrie, novembre, Paris, France.

- Rosele Chim P (2001) Renouveau économique et nouvelles technologies de l’information et de la communication, Revue Vie et Sciences Economiques, n° 157-158, spécial Nouvelle Economie, Printemps, Paris, France.

- Rosele Chim P (2003) Economie du cinéma de l’audiovisuel et de la communication, Le monde Caribéen et Hollywood, Edition EPU, Paris, France.

- Rosele Chim P (2009) Les Nouvelles Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication et le développement touristique des territoires, in Le développement du tourisme de santé de remise en forme et de bien-être, Edition EPU, Paris France.

- Rosele Chim P (2012) La gestion du développement des territoires et l’intelligence économique, Travaux d’HDR, Université de Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris, France.

- Galbraith JK (1967) Le nouvel Etat industriel, 3ème édition, coll. Tel, n° 143, Gallimard, Paris France.

- Liberation (2011) Petite Poucette, la génération mutante, Extrait du Journal du, Paris, France.

- Serres M (2012) Petite Poucette, Edition Le Pommier, Paris, France.

- Bourdin A. (2013) Le numérique: locomotive de la 3e révolution industrielle, Edition Ellipses, Paris, France.

- Dru JM (1992) Mémoire sur l’industrie publicitaire, BDDP (1998), OMNICOM (1998) et TBWA, Paris, France.

- Bassoni M, Liautard D (2005) Les technologies de l’information et de la communication en région Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur: illusion ou vraie révolution en gestation? in Lettre Electronique MIP, France. P. 95-100.

- Bassoni M, Joux A (2014) Introduction à l’économie des médias, Cursus, Edition Armand Colin, Paris, France.

- Greffe X, Sonnac A (2008) Culture Web, Edition Dalloz, Paris, France.

- Beuve J (2015) Le modèle industriel israélien: conditions du succès et défis futurs. Focus du Conseil d’Analyse Economique.

- Rosele Chim P (2016) Le film caribéen francophone et créole: nouvelle économie en développement et révolution numérique, Actes des CCEE, Régions Ultrapériphériques d’Europe, Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe.

- Rosele Chim P (2018) Le cinéma caribéen et amazonien d’identité francophone et créole: nouvelle économie en développement et révolution numérique, Revue Etudes Guadeloupéennes, Edition Jasor, Guadeloupe.

- Guillou B (1984) Les stratégies multimédias des groupes de communication, Edition La Documentation Française, Paris, France.

- Mouline A (1996) Les alliances stratégiques dans les technologies de l’information, Paris, Edition Economica, Paris, France.

- Kelly K (1998) New rules for the New Economy, Viking Press, New York, USA.

- Shapiro C, Varian HR (1999) Information rules: a strategic guide to the Network Economy, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, USA.

- Stigler GT (1968) The organization of industry, Irwin Dorsay, New York, USA.

- Schumpeter JA (1999) Théorie de l’évolution économique, Edition Dalloz, 2ème Edition, traduction de l’édition de 1926, Paris, France.

- Cohen D (2015) Le monde est clos et le désir infini, Edition Albin Michel, Paris, France.

- Blanchet M (2016) Industrie 4.0 Nouvelle donne industrielle, nouveau modèle économique, Revue Lignes de repères, Paris, France.

- Amin A (1994) PostFordism, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- Baumol W, Panzar J, Willig R (1982) Contestable markets and the theory of industry structure, Harcourt Bras Janovich, New York, USA.

- Chantepie P, Le Diberder A (2010) Révolution numérique et industries culturelles, coll. Repères, n°408, Edition La Découverte, Paris, France

- Coase RH (1997) La firme, le marché et le droit, Edition Diderot Multimédia, Paris, France.

- Colin N, Landier A, Mohnen P, Perrot A (2015) Economie numérique, Les notes du Conseil d’Analyse Economique, n° 26, Paris, France.

- Curien N, Muet (2004) la société de l’information, rapport pour le conseil d’analyse economique, la documentation française, paris, france.

- Fayon D (2013) Géopolitique d’Internet, Edition Economica, Paris, France.

- Fogel JF, Patino B (2013) La condition numérique, Edition Grasset, Paris, France.

- Gabszewiscz j, Sonnac N (2013) L’industrie des médias à l’ère numérique, coll. Repères, n°283, Edition La Découverte, Paris, France.

- Granjon F (2007) Société de l’information. Faut-il avoir peur des médias? Dossier sous coordination, Revue Contretemps, n°18, février, Paris, France.

- Ichbiah D (1995) Bill Gates et la saga Microsoft, Edition Pocket, Paris, France.

- Ichbiah D (2010) Comment Google mangera le monde, L’Archipel, Paris, France.

- Isaacson W (2011) Steve Jobs, Le livre de poche, Paris, France.

- Le Roy F, Yami S (2007) Les stratégies de coopétition in Revue française de gestion, n°176, Paris, France.

- Panhuys B (2008) La constitution des grands groupes de médias et Le pouvoir des groupes en question: étude des risques liés aux stratégies d’acquisition, Travaux de thèse de Doctorat, Université de Limoges, France.

- Panhuys B (2010) Le sport au caeur des stratégies des médias: quelle incidence sur l’organisation sportive? et analyse des stratégies d’entreprises leaders du marché (AOL-Time Warner, NBC Universal, Disney-ABC, Viacom CBS, News Corporation, Groupe Kirch, Canal+ filiale de Vivendi Universal), in Le basket professionnel. Analyse économique du spectacle sportif mondialisé, Centre de Droit et d’Economie du Sport, PULIM, Limoges, France.

- Toussaint-Desmoulins N (2015) L’Economie des médias, Collection Que sais-je? Edition PUF, Paris, France.