Spatio - Organizational Restructuring of the Banking Industrial Sub-Sector in Ibadan Metropolis

Clement Ebizimor Deinne*

Department of Geography, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Submission: March 31, 2018; Published: May 21, 2018

*Corresponding author: Clement Ebizimor Deinne, Department of Geography, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, Email: cedeinne@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Clement Ebizimor Deinne. Spatio - Organizational Restructuring of the Banking Industrial Sub-Sector in Ibadan Metropolis. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2018; 1(2): 555558. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2018.01.555558

Abstract

The purpose of his paper is to examine the spatial implications of restructuring financial institutions, factors influencing the reform and the changes perceived after restructuring financial institutions in Ibadan metropolis. Two major research instruments were adopted in this study, these are the In-depth Interview (IDI) and the use of structured questionnaire through participatory approach, the involvement of the respondents across different socio-economic groups ranging from students, bankers, civil-servants, traders and the unemployed. The result reveals a significant difference in the factors influencing the restructuring of financial institutions among different socio-economic groups in Ibadan metropolis at 0.05 significant level (P < 0.05).

Keywords: Spatial implications; Spatio-Organizational restructuring; Financial institution, Ibadan metropolis; Southwest Nigeria

Introduction

Spatial restructuring is consequently a complex process which operates not only at an inter-divisional level but also within divisions (Meegan, 1982). The financial sector in Nigeria has undergone radical spatial and organization changes since independence in 1960, Government policies such as the introduction of new legislation, changing market situation, and enabling technology, realizing the importance of a strong capital base to financial institutions the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has continued to specify the minimum paid-up share capital requirement for both existing and incoming banks over the years. Clearly, the new policy ushers in fundamental changes as it may see the demise or absorption of a significant number of the nations 89 banks resulting in perhaps only a score of financial institutions surviving (Ajayi and Oyetunde, 2004). A critical review of the literature shows a gap in knowledge on the spatial implications of organization restructuring of financial institutions. GeographicScholarship and the corpus of Social Science theory [1], focused on observable spatial changes and patterns and, for the most parts ignore the spatial implications of spatial processes and services.

The new industrial space is organized in a hierarchy of innovation and fabrication articulated in global networks. But the direction and architecture of these networks are submitted to the endless changing movements of cooperation and competition between firms and between locales. The new industrial space perhaps, spatial restructuring is organized around flows of information that brings together and separate at the same time their territorial components and office space. Castell states that the new global economy and the emerging informational society have a new spatial form, which develops in a variety of social and geographical context: Spatial forms and processes are formed by the dynamics of the overall social and spatial structure.

Further-more, social processes influence space by acting on the built environment [2] inherited form previous social-spatial structures. What is space? In science, it cannot be defined outside the dynamics of matter. In social theory it cannot be defined without reference to social practices. Castells [3] defines space as a material product, in relationship to other material products – including people – who engage in (historically) determined social relationships that provide space with a form, a function, and a social meaning. Time and space cannot be understood independently of social action. Castells speaks of time-sharing social practices, hereby he refers to the fact that space brings together those practices that are simultaneous in time. The proximity of material support is no longer of essence. Our society is constructed around flows: flows of capital, flows of information, flows of technology, flows of organizational interactions, flows of images, sounds, and symbols Castell [4].

This paper argues that organizational structural shifts within the financial sector have direct implications on the spatial structure and organization through a change in the spatial structure and level of services provided. As a result of this driving force of change organizations adopt a new paradigm to be more flexible, sensitive and adaptable to the demands and expectations of stakeholders, the perceived causes of restructuring and the resultant spatial implications such as opening of new branches, acquisition and merging of banks and financial institutions in southwest Nigeria.

This paper is organized into five sections: Apart from the introductory section which evaluates the Nigerian Banking industrial sector since independence. Section 2 presents the conceptual clarification of spatial implications of organizational restructuring of the banking industrial sub-sector as a theoretical principle. Section 3 presents the research methods, results and findings are presented in section 4 while section 5 concludes. The next sub-section briefly reviews the history of Nigerian banking, places this latest reform effort within the context of that history, and subsequently analyzes this reform effort, and the spatial implications of restructuring financial institutions in Nigeria.

Historical development of the banking industrial subsector in Nigeria

There were only 26 merchant and commercial banks operating in Nigeria in 1981 following the liberalization of banking licensing in 1991, the number rose to 89 by December 2000. Currently, the banking industrial sector in Nigeria is highly fragmented presenting significant opportunities for consolidation. The three largest banks currently operating in Nigeria (sometimes referred to as first generation banks) have their origins in the colonial period. The British Bank for West Africa (now called the first bank) was incorporated in 1892. This colonial bank later acquired by Barclays and now known as Union Bank, began operations in 1917 and the British and French Bank the precursor of the United Bank for Africa started in 1949. Wholly foreign owned but the Federal Government purchased majority share holdings in the mid 1970s. The United Bank for Africa have a commanding role. Collectively they employ over 27,000 people across more than 700 branches. Following the big three are a number of so called “second generation” banks notably, Zenith International Bank, Guarantee Trust Bank, Diamond Bank and Standard Trust Bank. Consequently, the number of banks rose considerably from 34 in 1987 to 42 in 1998 [5], 58 in 1990, 65 in 1992 and 66 in 1993. As at June 20 1996 [6], a total of 64 commercial banks were in operation-comprising 34 privately owned, 16 states owned and 14 federally owned banks.

Despite the phenomenal growth in the number of financial institutions, the industry is dominated by a few banks. However, since the late 1980s, the banking industry has been afflicted by widespread financial fragility; fifty-seven (57) banks almost half of the total number of banks in operation were regarded as distressed or potentially distressed by the regulatory authorities in 1995.(Business Times 25/9/95 p.3) [7]. The distressed banks result to outright liquidation, mergers and acquisition which must have had adverse consequences on the institutions and individuals. In anticipation of the adoption of universal banking in Nigeria in January 2001, the statutory minimum paid-up share capital for banks was reviewed from five hundred million naira (N500m) to one billion naira (N1b) in 2000, with a compliance dead line set at December 31 2002 [8]. For new banks however, the capital base was set at two billion naira (N2b) (Banking Supervision Annual Report, 2002).

Thus, a better understanding of the structural changes in the sector is of great importance to all stakeholders and regulators. The result of this new, much larger capital requirement was the consolidation of banks into larger entities. During this 18-month period, there were a number of mergers and acquisitions among Nigerian banks in order to meet this new capital requirement. In the end, the 89 banks that existed in 2004 decreased to 25 larger, better-capitalized banks. The introduction of the noninterest banking in Nigeria is expected to herald the entry of new markets and institutional players thus deepening the nation’s financial markets and further the quest for financial inclusion. In fact, the first fully licensed non-interest bank in the country (Jaiz Bank Plc.) started business on Friday, January 6, 2012.

Conceptual Clarifications and Review of Literature

The relevant literature to the study is reviewed under the following themes: Spatial restructuring, Location shift, Organizational restructuring, Sector change and Organizational change.

The coexistence of prosperous and relatively disadvantaged regions can have a cumulative socio-economic effects. ‘In essence the circularly and cumulative causation’ (CCC) developed by theorist such as Gunnar Myrdal (1957) provides a useful understanding of spatial inequality and the need for restructuring. Harvey (1989) space thereby acts as more than a prism through which inequalities and disadvantages are expressed, instead becoming a mechanism by which those inequalities are reproduced and reinforced.

Spatial restructuring

The central concern for Geographers is spatial analysis. As the international character on Geographical Education puts it some of the central concepts of geographical studies are location and distribution, place, people environment relationships, spatial interaction, and region [I.G.U.1992]. Spatial restructuring, perhaps spatial engineering is usually conceptualized in terms of the attempt at reorganizing space in order to benefit a people Ikporukp [9]. A good deal of spatial change occurs as a result of acquisition and merger, not only does this adds a whole new set of activities and locations to the acquiring firms network. Some degrees of spatial reorganization is occurring virtually all the time. Two broad types of spatial organizational change can be identified: In-situ-change and Locational shift Dicken [10].

Locational Shift

Locational shift involve abrupt change because it consist of either an increase or decrease in the number and location of units operated by the firm through the setting up of a branch plant and acquisition of plants belonging to another firm introducing a change in spatial organization. The whole corporate adjustment process is geographically kaleidoscopic (Dicken, 1986; Richard Florida and Martin Kenney, 1992). Spatial restructuring is consequently a complex process which not only at an interdivisional level but also within divisions (Massey and Meegan, 1982).

Organizational restructuring

At a more general level, analysis of industrial landscapes do not simply evolve according to fixed development trajectories. Rather they go through a dynamic process of change, transformation and reorganization. Such periods of dynamic restructuring combine technological change with sweeping organizational transformation Freeman [11]. The acceptance of an innovation is rather slow at the initial stage then followed by a rapid build-up as the innovation takes–off (Ajayi, 2002; Hagget et al, 1977). Restructuring and reforms have proceeded unevenly across firms and places, all explicit spatial conceptualization of what Schumpeter (1975) referred to as the process of “creative destruction” which he described as a major recasting of technology and organization, banks were consolidated through mergers and acquisitions new branches established introducing a change in spatial organization.

Organizations can locate themselves everywhere around the world. Mobile offices become more and more popular. Progress is required if you want to survive the ever changing society. Special skills are needed to manage organizations these days. It is not enough to manage a specific organization, you’ll have to manage processes and flows in which the organization is participating. These processes and flows are constantly changing and are connected in networks Castell [3].

New models of restructuring do not require major spatial shifts and the opening of the new geographic landscapes. Rather, the work and production process may be re-oriented and transformed in places as old organization structures and places are restructured and new social relations and even human behaviors are adopted within existing production geographic and industrial landscapes [12]. Hence, organizations no longer promote ‘lifetime’ employment instead, they offer employees learning opportunities and development options as well as career reaching and assessment tools. Corporate restructuring is normally associated with a major change in the nature or scale of the firms activities and the impetus which has driven firms to look for new locations has nearly always been the expansion of their business structure (Luttrell, 1962).

According to Young (1928) structural change alters the prospects for industrial activity by revealing new opportunities, and a better understanding of how firms are being organized and reorganized, how internal and external power structures are configured and reconfigured (Markusen, 1999). Miles et al., (1999) provide an interesting perspective on the supposed evolution of dominant organizational firms and the underlying parameters of this progression include a shift in the firms asset through information to knowledge and a shift in firms capacity from specialization and segmentation through flexibility and responsiveness, to design creativity. The surviving plants organizational status may remain unchanged, may shift from one organizational category to another related to change of ownership, to the process of merge and acquisition which has been such a pronounced feature of industrial change in recent decades.

Sectoral change and organizational change

Sectoral [13] change and organizational change are probably closely related but they are by no means synonymous. Some firms perform better or worse than others in the same economic sector. Some sectors are more prone to major organizational adjustment e.g. merger or rationalization. Much of the change seems to present a permanent shift in social, economic and organizational competitive structures (Mckinley, Sanchez and Schick, 1975).

Some institutional theorist argue that three specific institutional forces (coercive isomorphism, mimetic isomorphism and normative isomorphism) have played a significant role in the spread of corporate restructuring, expansion and downsizing (Maggio and Powell, 1983). Coercive Isomorphism pressures organizations to conform to institutional rules and policy that define legitimate structures and management activities. While Mimetic Isomorphism pressures organizations to mimic the actions of firms recognized as industry leaders. And Normative Isomorphism which emerges through the management practices learned at professional conferences, seminars, traditional university curriculum, education programs, and formal and informal professional networks-Pressures managers to conform to currently accepted management practices and philosophies (Mckinley, Sanchez and Schick, 1995) [14].

A variety of institutions will provide financial services in Nigeria in the future. The” one size fits all” universal banking model will weaken and the CBN will license institutions to provide different services (corporate banking, small and medium sized business lending, Islamic banking) to different markets. This change in licensing requirements will create opportunities for financial service providers, other than commercial banks, to enter the Nigerian market.

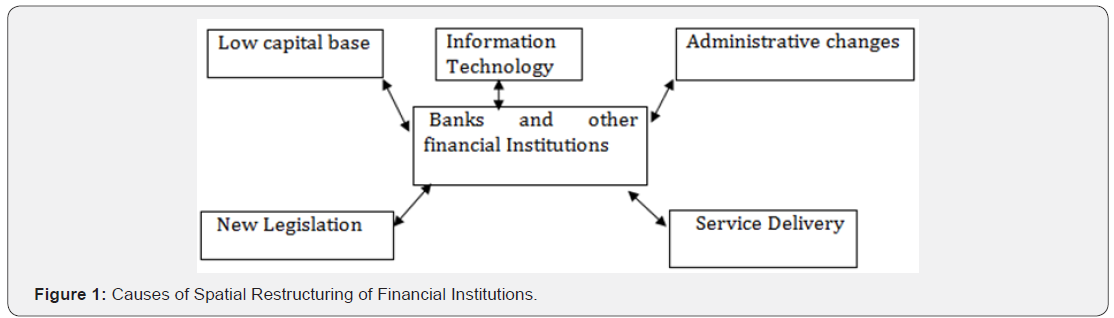

Causes of Restructuring Financial Institutions

The reform was designed to strengthen the system and individual banks to re-conceptualize their mission in a rapidly growing economy (Lance, 2004) [15]. In 2004 [16], the banking industry of Nigeria consisted of 89 banks. The industry was fragmented into relatively small, weakly capitalized banks with most banks having paid in capital of $10 million or less. The best capitalized bank had capital of $240 million as compared to Malaysia where the least capitalized bank had capital of $526 million at the time. The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) such as communication-network, internet access, digital database technology and political factors such as government innovation, new legislation and reformation, poor management, low capital base and fraud are the major causes of restructuring financial institutions in Nigeria. Most respondents interviewed in the study said embezzlement of funds, fraud, low capital base, and so on are the major factors influencing restructuring of financial institutions in Nigeria, (Figure 1). Figure 1 indicates the causes of restructuring financial institutions, which make organizations adopt a new paradigm to be more sensitive, flexible and adaptable to the demands and expectations of customers and stakeholders. The review of literature generated the hypothesis which states that there is a significant difference in the causes and spatial implications of restructuring financial institutions among different socioeconomic groups.

Research Methodology

Study area

A survey research design was adopted in which Ibadan the study area was purposively selected. The reconnaissance survey covered Ibadan metropolis. Ibadan was created in 1829 as a war camp for warriors coming from Oyo, Ife and Ijebu. A forest site and several ranges of hills, varying in elevation from 160 to 275 meters, offered strategic defense opportunities. Ibadan is located on latitude 7oN and longitude 4oE. The temperature of any location is a function of two major factors – lat and attitude. The altitude of the surroundings land surface is the local factor responsible for the high temperature. Ibadan is about 300ft above sea level. This gives a drop of 1Oc in the temperature. Generally, Ibadan has 29.5Oc or 30.5Oc with internal variation resulting from altitude. Other factor responsible for variation in temperature is the distance from the city centre. The core areas experience higher temperature than the fringes or peripheral areas.

Moreover, its location at the fringe of the forest promoted its emergence as a marketing centre for traders and goods from both the forest and grassland areas. Ibadan thus began as a military state and remained so until the last decade of the 19th century. The personal interview with employees and customers of financial institutions selected based on 2007 World Bank Ranking.

Research instruments

Two major research instruments were adopted in this study, these are the In-depth Interview (IDI) and the use of structured questionnaire through participatory approach, the involvement of the respondents across different socio-economic groups ranging from students, banker, civil servant, unemployed, and so on. About two hundred structured questionnaire copies were administered to both employees (service providers) and customers these are people who transact business with these financial institutions in these business districts. Data collected from the survey were subjected to quantitative analysis [18] after the (IDI) data was computed and analyzed using SPSS.

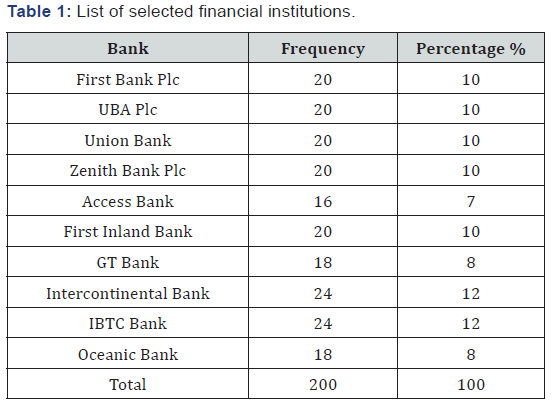

A questionnaire each was structured for both employees (service providers) and customers across different socioeconomic groups. The independent variables in this study are: the various occupational groups, gender and so on, while the dependent variable is perceived spatial restructuring. Occupational groups was classified into: students, banker, business, civil servant, unemployed. The questionnaire was proportionally administered among employees and customers in financial institutions situated within Ibadan metropolis along the major business districts such as Dugbe, Iwo-Road, Ring- Road, Orita-Challenge and Bodija axes which are the higher order central places of commercial importance in the City (Table 1).

Discussion of Results and Findings

The presentation of major findings of the study were divided into four segments: The first segment contained information on the socio-economic profile of the respondents (customers). The second segment pertains to the relationship between the socio-economic groups and causes of restructuring financial institutions, while the third and the fourth segments discussed the spatial implications of restructuring financial institutions and the changes perceived after restructuring financial institutions.

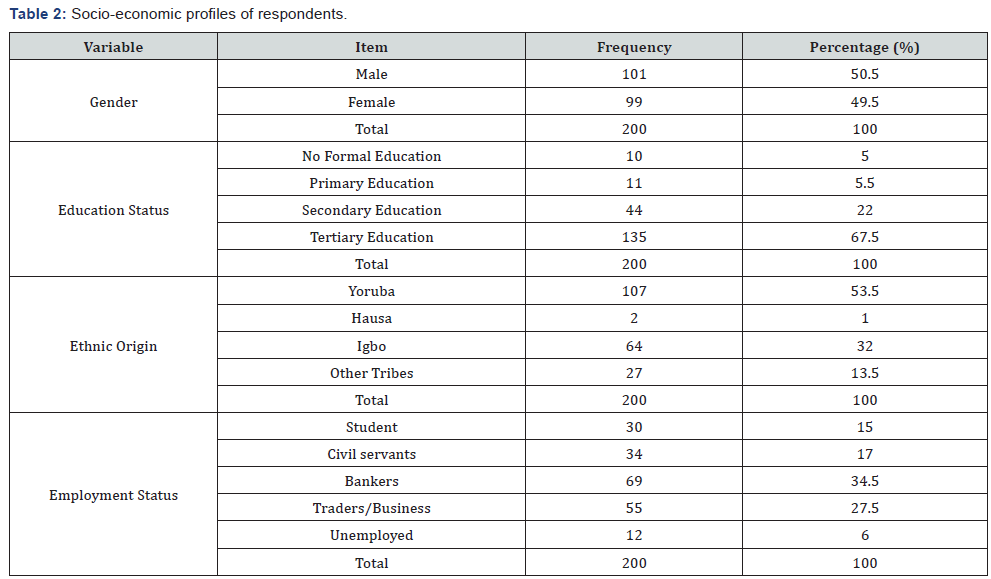

Socio-economic characteristics of respondents

The socio-economic profile of the respondents (customers) and service providers include: sex, ethnic origin, education and employment status. Table 2 shows that 50 percent (101) of the respondents are male, while 49.5 percent are females. Most of the respondents (53.5%) are Yoruba. In addition, respondents in the banking profession represents (34.5%), businessmen and traders (27.5%), while (67.5%) of the survey respondents had tertiary education (Table 2).

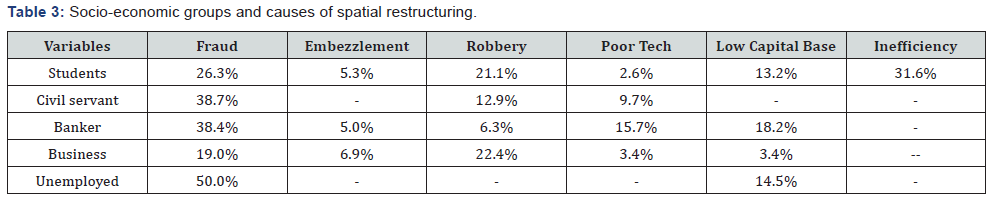

Table 3 shows that the occupation of the respondents influence their perception of the causes and spatial implications of restructuring financial institutions [18], 26.3 percent of student respondents indicate fraud while 31.6 percent indicate inefficiency as the major causes of restructuring financial institutions. Moreover, 38.7 percent of the civil servants indicate fraud while 12.9 percent indicates poor technology as the major causes of restructuring. 38.4 percent of bankers indicate fraud, while 18.2 percent indicates low capital base as the major cause of restructuring.19 percent of traders and business men indicates fraud while 22.4 percent indicates robbery as the major cause of restructuring while the unemployed representing 50 percent indicates fraud and 14.5 percent indicates low capital base as the major cause of restructuring financial institution. The results reveal a significant difference in the causes of restructuring financial institutions among different socio-economic groups in Ibadan metropolis at 0.05 significant level (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Spatial Implications of Restructuring Financial Institutions

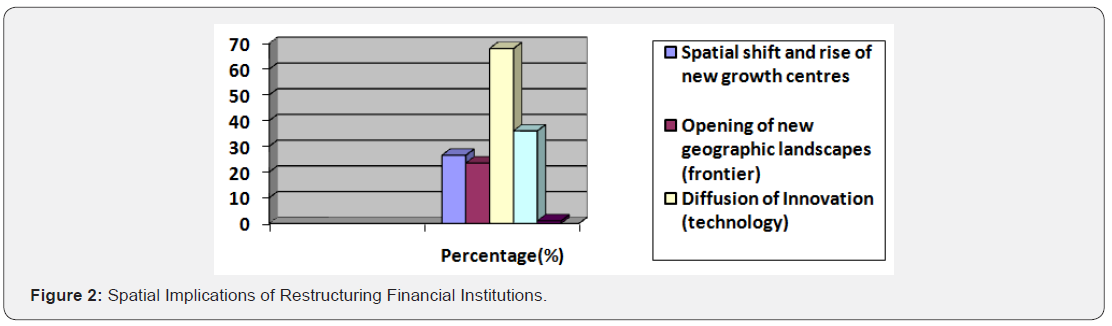

Figure 2 presents the spatial implications of restructuring financial institutions, 53 (26.5%) of the respondents perceived spatial shift and growth of new branches and banks as the implications of restructuring, 47 (23.5%) indicates opening of new geographic frontiers and landscapes, 136 (68%) indicates diffusion of innovation, while 72 (36%) indicates restructuring social relations as the implication of restructuring financial institutions, graphically illustrated in Figure 2.

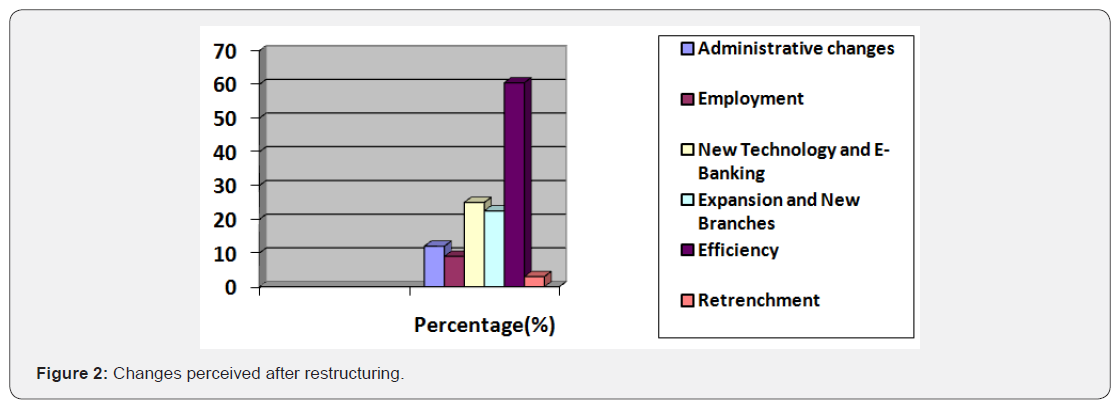

Figure 3 shows the changes perceived after restructuring financial institutions, 24 (12%) of the respondents perceived Administrative changes, 18 (9%) indicates Employment opportunities, 50(25%) indicates diffusion of innovation and new technology, while 45 (22.5%) indicates expansion and new branches as the change perceived after restructuring financial institutions, 121 (60.5%) of the respondents indicates efficiency as a major change, while 6 (3%) indicates job loss as a major change perceived after the restructuring of financial institutions. The result of this new, much larger capital requirement was the consolidation of banks into larger entities. During this 18-month period, there were a number of mergers and acquisitions among Nigerian banks in order to meet this new capital requirement. In the end, the 89 banks that existed in 2004 decreased to 25 larger, better-capitalized banks. After the restructuring, surviving and hegemonic banks acquired and merged with the weak and liquidated banks resulting into opening of new branches and reconcentration of offices in the Central Business District (CBD), commercial centers and new geographical frontiers or new business locations (Appendix 1-3).

Conclusion

Spatial forms and processes are formed by the dynamics of the overall social and spatial structure. Further-more, social processes influence space by acting on the built environment inherited form previous social-spatial structures. A good deal of spatial change occurs as a result of acquisition and merger which add a whole new set of activities and locations to the acquiring firms network. Some degrees of spatial reorganization is occurring virtually all the time. The distressed banks result to outright liquidation, mergers and acquisition which had adverse consequences on the existing spatial structure such as spatial implications of restructuring financial institutions through expansion and establishment of new branches.

Acknowledgement

I acknowledge Dr. D.D. Ajayi of the Department of Geography, University of Ibadan for his immense contributions and supervision of this project.

References

- Luisetto M, Behzad NA, Ghulam RM (2018) Mindset Kinetics-Under Toxicological Aspect. Psychol Behav Sci Int J 8(2): 555731.

- Mauro L (2017) Attitudes and Skills in Business Working Settings: A HR Management Tool. Bus Eco J 8: 291.

- Luisetto M, Khan FA, Cabianca L, Mokbul MI, Rafa AY, et al. (2016) Amygdala pharmacology and crime behavior, dysfunctions to be considered as a disease? International Archives of BioMedical and Clinical Research 2(2).

- Luisetto M (2016) Velocity Management Strategy in Healthcare. J Bus Fin Aff 5: e148.

- Luisetto M (2017) New Theories in Management Decision Making Systems. Innovative Journal of Business and Management 6(4): 1.

- Luisetto M (2017) Intra-Local Toxicology Aspect Time Related in Some Pathologic Conditions. Open Acc J of Toxicol 2(3).

- Gosling J, Mintzberg H (2003) The five minds of a manager. Harv Bus Rev 81(11): 54-63.

- Kumar S, Adhish VS, Chauhan A (2014) Managing self for leadership. Indian J Community Med 39(3): 138-142.

- Jamieson SD, Tuckey MR (2016) Mindfulness Interventions in the Workplace: A Critique of the Current State of the Literature. J Occupy Health Psychol, 22: 180-193.

- Herrman H, Stewart DE, Diaz-Granados N, Berger EL, Jackson B, et al. (2011) What is resilience? Can J Psychiatry 56(5): 258-265.

- Zakariasen K, Victoroff KZ (2012) Leaders and emotional intelligence: A view from those who follow. Healthc Manage Forum 25(2): 86-90.

- Dixon T (2012) Educating the Emotions from Gradgrind to Goleman. Res Pap Educ 27(4): 481-495.

- Luisetto M (2017) Jurisdictional Consequences in some brain condition. Neurochem Neuropharm.

- Luisetto M (2017) New Theories in Management Decision Making Systems 6(4).

- Luisetto M (2017) Brain & Transmission Signal Modulation theranostic of brain disorder.

- Sergerie K, Chochol C, Armony JL (2008) The role of the amygdale in emotional processing: a quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav 32(4): 811-830.

- Luisetto M (2016) Velocity Management Strategy in Healthcare. J Bus Fin Aff 5: e148.

- Luisetto M(2016) Sharing Economy and Healthcare Today: ICT, Knowledge, Skills, Projects, Practical Experience in Improving Clinical and Economic Outcomes. J Bus Fin 5: 207.

- Wen L, Yang H, Bu D, Diers L, Wang H (2018) Public accounting vs private accounting, career choice of accounting students in China. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 8(1): 124-140

- Singh S, Wang H, Zhu M (2017) “Perceptions of Social Loafing during the Process of Group Development”. Midwest Academy of Management Conference Proceedings Chicago, Working paper, Illinois, USA.

- Singh S, Wang H, Zhu M (2017) Perceptions of Social Loafing in Groups: Role of Conflict and Emotions. Working paper, Illinois, USA.