The Effect of Various Classes of Malocclusions on the Maxillary Arch Forms and Dimensions in Jordanian Population

Raghda WK Al Shammout1*, Osama Al Jabrah1, Khuzama Aburumman1, Ahmad M. Alhabahbah1 and Wasfi Almanaseer22

1Department of Dentistry, Al-Hussein Hospital, Jordan

2Division of Dentistry, Prince Zaid Hospital, Jordan

Submission: May 20, 2016; Published:June 30, 2016

*Corresponding author: Raghda Al Shammout; Department of Dentistry, Al-Hussien Hospital, KHMC; Royal Medical Services. PO Box 1133,Postal Code: 11732 Marj Al-Hamam, Amman, Jordan, Tel: +962 6 571 4364; +962 77 2002952; Email:raghdashammout@hotmail.com

How to cite this article: Al-Shammout RWK, Al-Jabrah OA, Aburumman KK, Alhabahbah AM, Almanaseer WA. The Effect of Various Classes of Malocclusions on the Maxillary Arch Forms and Dimensions in Jordanian Population. Adv Dent & Oral Health. 2016; 2(1): 555579. DOI: 10.19080/ADOH.2016.02.555579

Abstract

Aim: The objective of this study was to determine the differences of clinical maxillary arch forms in Angle Class I, II, and III using arch dimension parameters.

Materials and method: A total of 124 (76 females and 48 males) fully dentate Jordanian subjects (mean age=18.34±4.26; range=14-22 years) were clinically examined and divided into 3 groups according to Angle’s classifications (Class I, II and III). Study casts were made and measured for 4 linear measurements of maxillary cast dimensions were taken (Inter-canine and inter-molar widths; and canine and molar depths). Canine W/D and molar W/D ratios were calculated. Arch form was determined according to measurements and related to occlusal pattern. The commonest malocclusion was class I (54.8%), followed by class II (37.9%) and class III (7.3%). Statistically significant differences were recorded in arch widths (p<0.05); Class III maxillary dental arches (W=37.8mm) were narrower than Class I (W=38.9 mm) and Class II dental arches (W=40.6mm) were the widest. In Class I: 55% of arches were ovoid, 40% tapered and 5% square. In Class II: 73% tapered 24% ovoid, and 3% square. In Class III: 45% tapered, 35% ovoid and 20% square. Measurements were significantly (p<0.05) higher in males than in females. No gender differences in canine and molar W/D ratios were recorded. Although more males had Class III, more females had Class II arches but the differences were not significant.

Conclusion: Before orthodontic treatment, the arch form should be determined in relation with patients’ occlusal pattern to achieve best esthetic, functional and stable arch form out-come.

Keywords: Arch form; Angle’s classification; Malocclusion; Maxillary Arch; Orthodontics

Introduction

The dental arch form is defined as the curving shape formed by the configuration of the bony ridge [1]. Arch form, dimension and variations obtained by orthodontic treatment has been studied for many years by several authors [2-4]. Consideration of the arch form is of paramount importance, because it is imperative that the arch form should be examined before embarking upon the treatment as this gives valuable information about the position into which teeth can be moved if they are to be stable following treatment [5].

Different methods have been developed to describe the dental arch morphology ranging from simple classification of arch shape [6] through combinations of linear dimensions [7,8] to complex mathematical equations [9,10].

In 1932, Chuck [11] classified the arch forms as tapered, ovoid and square for the first time. These arch forms can also be expressed as narrow, normal and wide [6]. Especially in determining the arch wire forms utilized at the initial phase of the treatment, he advocates that making a choice between these three forms would be better than using a single arch form [7]. The arch form should be determined in relation with each patients’ pre-treatment dental model and especially in relation with each patients’ ethnic group in order to achieve an esthetic, functional and stable arch form out-come [5,7].

Several researchers recognize that there is variability in the size and shape of arch form in relation to Angle’s classes of malocclusion [5,7,8,12-18]. In addition, the width, length and depth of dental arches have had considerable implications in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning in a modern dentistry based on prevention and early diagnosis of oral disease [4,19-22].

Several researchers studied the mandibular arch [5-8,14,18,22-25] while some others studied the maxillary arch [2,13,21,26] however, many others studied both arches [1,3,4, 9-11,12,15-20,27-31].

With the availability of different preformed shapes and sizes of arch wires, different studies highlighted the importance of selection of patients clinical arch form and customization of arch wire [5,8] in addition, determination of arch shape may be used as a guide to fabricate customized arch wires, or even an entire fixed orthodontic appliance system [29].

The importance of this study comes from the fact that studies investigating the differences in the maxillary arch forms in various types of Angle’s classes are scarce. Therefore, the present study may serve as population study and a database for future comparisons and to obtain baseline information on the morphological arch dimensions of the fully dentate population since these variations highly influence orthodontic and prosthetic rehabilitation of patients.

The differences in various types of Angle’s classification (Class I, II, and III) may cause changes in relation to the clinical maxillary arch forms and variations in its dimension. Therefore, it was hypothized that maxillary arch dimensions and morphology is not affected by different types of Angle’s classes and between genders.

Although there have been studies one on the evaluation of arch forms in various groups, to the authors’ knowledge, no such research has been performed on the Jordanian population; thus this study aimed to determine the differences of clinical maxillary arch forms in Angle Class I, II, and III in the Jordanian population by identifying its morphological variations and to evaluate gender differences with respect to arch dimension parameters.

Materials and Method

A cross-sectional study of Jordanian males and females who are fully dentate with different arch skeletal patterns, in the City of Amman who attended the Orthodontic Clinic, Outpatients Clinics, Department of Dentistry, Al-Hassan Hospital, King Hussein Medical Center, Royal Medical Services. A random sample for the study were selected from the general population, who fulfilled objective diagnostic criteria and exposed to clinical oral and dental examinations.

Ethical approval

FThe study was conducted for all patients who provided verbal informed consent after it was approved by Head of the Dental Specialities of the Department of Dentistry and The Human Research Ethics Committee (No.1/2014 dated 6th January 2014) at the Royal Medical services.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Subjects with different age groups who accepted to participate were fully dentate with no dental anomaly and with no history of congenital abnormality, those who were not exposed to any orthognathic surgical procedure, no missing tooth/teeth and with no extensive restorative procedure (i.e. crown and bridge work); and accepted to undergo clinical oral and dental examination, were able to understand and agreed with procedures carried out and used (such as taking alginate maxillary impressions) in the study and who were willing to accept the protocol and gave informed consent were included. Exclusion criteria were subjects with history of orthognathic surgery, missing teeth, crown and bridge work, removable partial denture prostheses, as well as those who did not agree to participate.

Participants

A total of 124 (76 females and 48 males) fully dentate Jordanian subjects with mean age of 18.3±4.3 (ranged between 14 and 22) years; were clinically examined and divided into 3 groups according to Angle’s classifications (Class I, II and III).

All recruited patients were subjected to clinical examination, a specially designed form concerning the patient’s demographic data including age, gender, medical insurance number, occupation and residence was filled by one of the authors.

Measurements

For each participant, alginate impression of the maxillary arch was taken, and poured in dental stone to form a stone cast (positive replica).

A stone cast was then made and marked with five reproducible reference points (with a 2H pencil), these were: mid-mesioincisal edges of central incisors, canine tips, mesiobuccal cusp tips of the first permanent molars used to perform measuring four linear measurements (Figure 1).

- Inter-canine width (ICW):The distance between right and left canines, measured from the tip of the canine tooth.

- Inter-molar width (IMW):The distance between the right and left first molars, measured from the highest point on the mesiobuccal cups of upper first molar tooth.

- Canine depth (CD):The shortest distance from a line connecting the canines to the origin between the central incisors.

- Molar depth (MD):The shortest distance from a line connecting the first molars to the origin between the central incisors.

Two proportional ratios were calculated:

- Canine Width/Depth (Wc/Dc) ratio:the ratio of the inter-canine width and the canine depth.

- Molar Width/Depth (Wm/Dm) ratio:the ratio of the inter-molar width and the molar depth.

All measurements were performed using Fowler electronic digital caliper (Figure 2), the accuracy of the measurements was set at ±0.01 mm.

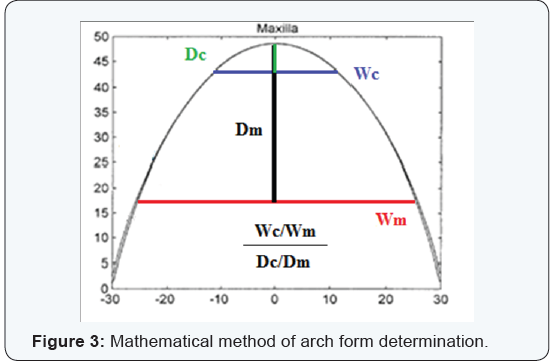

Arch form was determined mathematically according to a formula [(Wc/Wm) / (Dc/Dm)] using the values obtained from the measurements. The mean measured data on the maxillary arch was used to determine the arch form and related to occlusal pattern (Figure 3).

When the Wc/Wm ratio increases or the Dc/Dm ratio decreases, the arch becomes squarer. On the contrary, when Wc/ Wm ratio decreases or Dc/Dm ratio increases, the arch gets a more tapered form. Therefore, the formula is used to describe the arch form.

When this ratio of a dental arch is within the range of mean±1 SD, we can assume the arch form is ovoid. However, when this ratio for an arch form is more than mean+1 SD, we can consider the arch form as square. Finally, when the ratio is less than mean +1 SD, we can consider the arch form as tapered [9].

Methods error

Reliability of examiners was assessed by examining internal consistency and reproducibility. Clinical examinations and measurements were performed by two independent examiners (66 subjects from one examiner and 58 from another examiner). They used the same orthodontic evaluation in the clinical examination for classifying occlusal relationship and standard method in the measurements. Inter-examiner variability and bias in evaluation were assessed by performing clinical examination 15 (12.1%) randomly selected subjects and re-measuring their casts by each examiner. Student’s t-test were performed for inter-examiner reliability evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistic Version 17 (SPSS Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA). Chi square and Student’s t-test were used to compare the means of dimension measured on the casts between different age groups and in both genders. In addition, one-way ANOVA was used for the comparisons between different arch forms and the skeletal patterns. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals about the mean were constructed for differences. Level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Paired t-test revealed no statistically significant deviation between the examiners’ clinical examination evaluation at a 5% significance level (in 100%). Paired t-test revealed no statistically significant deviation between the examiners’ measurements at a 5% significance level (mean difference 1.98±0.15; p=0.942). As there was strong association and small mean difference between the two examiners, it was assumed that the other data collected from clinical examinations and measurement evaluations would be reliable.

A total of 124 fully dentate Jordanian subjects with mean age of 18.3±4.3 years (ranged between14 and 22) years. There were 48 (38.7%) males with mean age 18.7±4.7 (ranged 15-22) and 76 (61.3%) females with mean age 18.0±4.1 (ranged 14- 21) years. Females were slightly younger than males, but the difference were not significant (t-test=0.47; p=0.95).

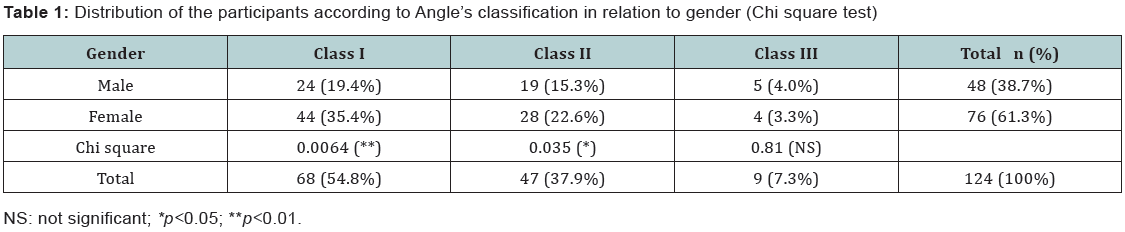

The commonest class was class I (54.8%), followed by class II (37.9%) and class III (7.3%). Significantly, more females had Class I (p<0.01) and Class II (p<0.05) occlusal relationship compared with males. On the contrary, more males had Class III relation compared with females but the differences were not statistically significant (Table 1).

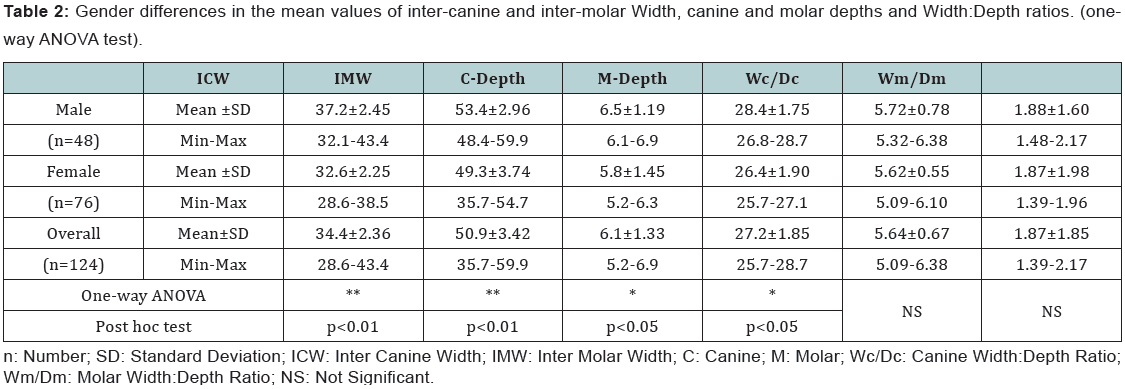

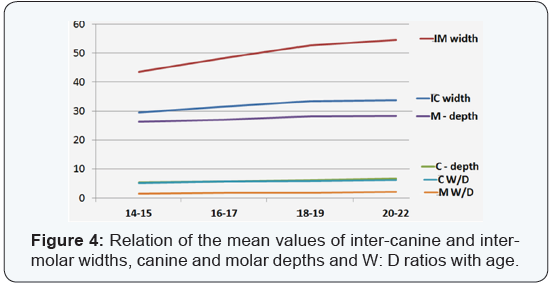

(Table 2) shows the gender differences in the mean canine and molar width and depth measurements and width: depth ratios. The mean values of all width and depth measurements were significantly (p<0.05) higher in males than in females. However, no gender differences in canine and molar W/D ratios were recorded. (Figure 4) shows the relationship between the mean values of inter-canine and inter-molar widths, canine and molar depths and W:D ratios with age. All width and depth measurements increased with age, inter-molar measurements recorded the steepest increase with age.

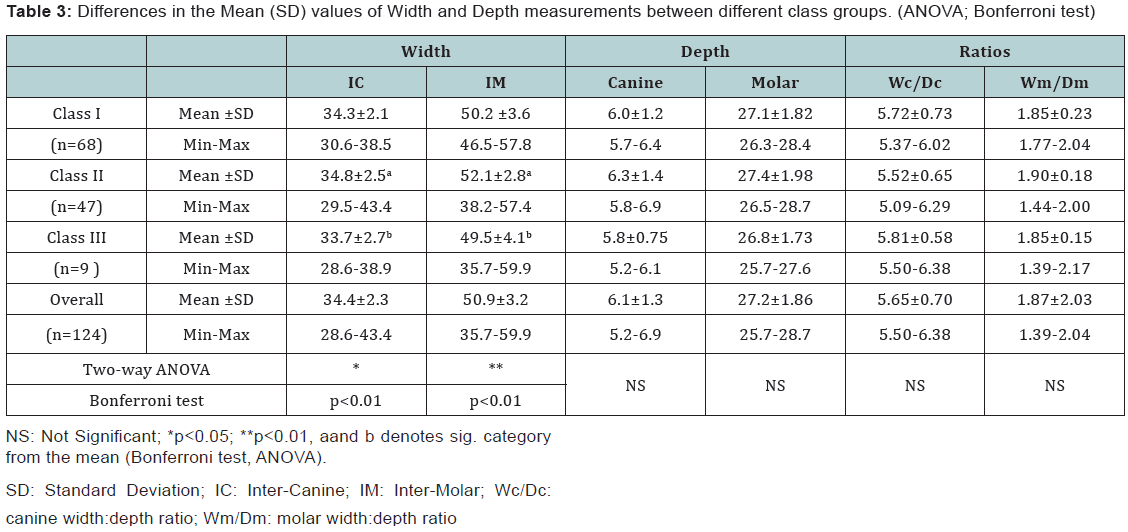

Statistically significant differences were recorded in arch width measurements (p<0.05). Class III arches, (Wc=33.7±2.7mm and Wm=49.5±4.1) are narrower than Class I (Wc=34.3±2.1mm and Wm=50.2±3.6) (p<0.01) and Class II dental arches (Wc=34.8±2.5mm and Wm=52.1±2.8) are the widest (p<0.05). However, there were no statistical significant differences between different classes in depth and width: depth ratios. (Table 3).

NS: Not Significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01, aand b denotes sig. category from the mean (Bonferroni test, ANOVA).

SD: Standard Deviation; IC: Inter-Canine; IM: Inter-Molar; Wc/Dc: canine width:depth ratio; Wm/Dm: molar width:depth ratio

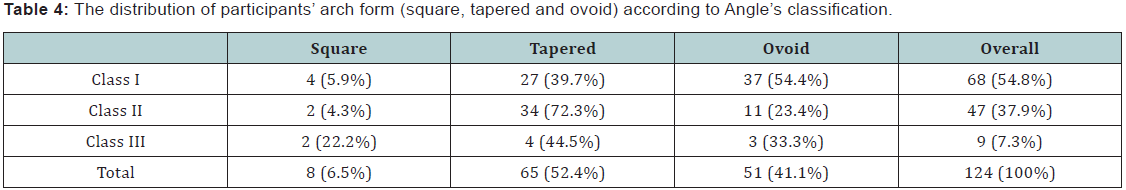

(Table 4) shows the distribution of participants’ arch form (square, tapered and ovoid) according to Angle’s classification.

Analyses of data according to the mathematical formula show that 52.4% of subjects have tapered maxillary arches and 41.1% ovoid. However, the least common arch form is the square which is recorded in only 6.5%. The commonest arch form in class I was the ovoid followed by tapered, however, in class II and class III subjects, the commonest arches were tapered.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the differences of clinical maxillary arch forms in Angle Class I, II, and III using arch dimension parameters, the sample was representative of a group of Jordanian population of dental patients that attended conservative and orthodontic dental clinics for a period of 6 months.

The size and shape of the dental arches have considerable implications for orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. These have an effect on the space availability, stability of dentition, esthetics and health of the periodontium [5].

In this study, more than 60% of the participants were women, although there was no statistically significant difference in the mean age between genders, women were slightly younger than men. In addition, the age distribution was limited with 14-22 in order to eliminate the variations in arch dimensions related with age. In addition, the age-related changes in the mean values of inter-canine and inter-molar width and depth measurements and W: D ratios shows a little gradual increase with age, however, the inter-molar measurements recorded the steepest increase with age.

After examining the differences in arch width in relationship with age, Bishara et al. [32] stated that although they had observed a reduction in canine width between 13-26 and 26- 45 in men and women, only the reduction detected in women between 26-45 was statistically important. Even though there is an increase in mandibular canine width until 13 years; this increase is found to be statistically important in boys until 8 and in girls until 13 years of age. After 13 years of age, the canine width shows a reduction in 25 and 45 years. In Bishara’s study the inter-molar width did not show a significant change between 13-26 and 26-45 years.

In the present study, gender-related differences were recorded in all arch width and depth measurements. When comparing arch dimensions with regard to gender, it was found that they are remarkably higher in males than females. These findings are in accordance with a previous study [33]. In an evaluation of arch width and depth measurements, it has been reported that these values are 3%-5% higher in boys [27]. It has been stated that the arch depth decreases in canine, first and second premolar and first molar teeth area in both genders [34].

The results that showed no differences in boys and girls were reported previously [18]. In most of the studies, although the values are less in girls, there is a relationship with the gender and arch dimension of the samples. It was postulated that there were significant differences related with gender only in the transversal dimensions [35]. In present study even though there are significant differences with respect to gender and canine/ molar width, both of the measurements are found to be higher in boys. Although boys possess a wider arch form than girls, there is an overall agreement that there is no gender variance with respect to arch form [36]. As it can be derived from these results, no statistically significant variances were found between gender and arch form.

The results of this study demonstrated that 54.8% of subjects were class I, 37.9% class II and the least (7.3%) were class III. In addition, significantly, more females had Class I and Class II occlusal relationship compared with males. On the contrary, more males had Class III relation compared with females but the differences were insignificant.

Similar findings were reported by Murshid [8] who found that class I was most prevalent (58.2%), followed by class II (32.7%) and class III (5.7%), in addition, it was reported that 58% were class I, 40% were class II and only 2% were class III [18]. However, Tajic et al. [5] reported that class II was the most prevalent (47.5%) followed by class I (45.8%) and the least was class III (6.7%). These differences could be attributed to racial variation in study samples.

Upon examination of the arch dimension differences between Angle classes, this study revealed statistically significant differences between classes in terms of arch width measurements (p<0.05). Class III arches were significantly narrower than Class I (p<0.01) and Class II dental arches were significantly the widest (p<0.05). However, the differences between different classes in depth and width: depth ratios were insignificant.

The molar width increase in Class II arches can be explained by buccal tipping of the anterior teeth in Class II development and flattening of the anterior area besides the lateral growth of the tongue due to the decrease of the molar depth [13,14]. In our study, when maxillary canine and molar depths were considered, no difference could be detected between Class I, II and Class III, also, upon comparison of these groups together in terms of width-depth ratios, no statistically significant differences were observed.

Arch shapes may also define characteristics of a particular occlusion group. Othman et al. [31] used tapered, square and ovoid arch form templates to evaluate the arch forms of angle class I, II and III. In this study, analyses of data according to the mathematical formula show that 52.4% of subjects have tapered maxillary arches and 41.1% ovoid. However, the least common arch form is the square which is recorded in only 6.5%. The findings of this study were similar to that reported in previous studies [7,12].

When comparing the arch form (square, tapered and ovoid) according to different classes, the commonest arch form in class I was the ovoid followed by tapered, however, in class II and class III subjects, the commonest arches were tapered. These findings strongly suggested that ovoid form should be considered when dealing with Class I cases and tapered form when Class II and III. The findings of this study are supported by the following previous studies [8,13,18].

The aim in specification of the arch form was to evaluate the final arch form which will be obtained by the use of fixed orthodontic appliances in patients who have referred to orthodontic clinic due to orthodontic malocclusion. In recent studies this arch form which is thought to be more realistic is preferred in determining the individual arch form [9,14].

Several studies used arch form templates for the evaluation of photo-copies of dental models, these are the 3 type of (narrow, normal and wide) arch forms specified by Paranhos et al. [6] and used by Chuck [11] for the first time in 1932. In this study, however, the maxillary arch form was determined mathematically using the values of width and depth obtained from the measurements [9,13].

The importance of this study is that determination of arch form in relation to different occlusal pattern is a prerequisite to orthodontic treatment in order to obtain the best outcome. As far as, esthetics is concerned, tapered arch form presents a better smile arc than square arch form which tends to provide a flatter smile arc which is not esthetically pleasing [37]. Space availability and stability of dentition are the factors of particular significance especially in a tapered arch group as the intercanine width is the shortest comparing the ovoid and square variety. Any arch expansion in the tapered arch group is deleterious for proper alignment of the lower labial segment since this region is constrained by circumoral musculature [5].

The differences in the various types of malocclusions (Angle Class I, II and III) may affect the maxillary arch form and in the distribution of morphological arch dimension. The present study that provides information concerning the differences of clinical maxillary arch forms in Angle Class I, II, and III demonstrates a baseline knowledge by identifying its morphological variations and evaluating gender differences with respect to arch dimension parameters Jordan refutes the null hypothesis./p>

Although many researchers studied the differences in the maxillary arch forms in various types of occlusal patterns, but it was difficult to compare their results with ours due to variations in the variables incorporated and racial differences.

One of the limitation of this study was small sample size and limited participation rate, thus it does not represent Jordanian population as a whole. In addition, the method used gives information about arch form mathematically ignored the perceived personal judgment, thus other methods to determine arch form was not considered. Another disadvantage was that the mandibular arch form was not considered.

Therefore, further research is still needed to overcome the limitations of this study which includes studying a larger sample and including other methods of arch form determination, different age groups and incorporation of mandibular arch form may be needed before the results of this study can be applied on the general population.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this study and due to the lack of studies aimed at maxillary arch form variances in Jordan, the following conclusions can be withdrawn:

- The commonest class was class I (54.8%), followed by class II (37.9%) and class III (7.3%). Significantly, more females had Class I (p<0.01) and Class II (p<0.05) occlusal relationship compared with males.

- The mean values of all width and depth measurements increased with age and were significantly (p<0.05) higher in males than in females.

- Significantly, class III arches are narrower than class I (p<0.01) and class II arches are the widest (p<0.05).

- The most frequently seen arch form was the tapered (52.4%) and ovoid (41.1%)., the least frequent one was the quare one which is recorded in only 6.5%.

- The commonest arch form in class I was the ovoid followed by tapered, however, in class II and class III subjects, the commonest arches were tapered.

With this study, it is foreseen that the arch form should be determined in relation with each patients’ pre-treatment maxillary dental model in order to achieve the best esthetic, functional and stable arch form out-come.

References

- Walter DC (1953) Changes in the form and dimensions of dental arches resulting from orthodontic treatment. The Angle Orthodontist 23(1): 3-18.

- Halicioglu K, Yavuz I (2014) Comparison of the effects of rapid maxillary expansion caused by treatment with either a memory screw or a Hyrax screw on the dentofacial structures - transversal effects. Eur J Orthod 36(2): 140-149.

- Miyake H, Ryu T, Himuro T (2008) Effects on the dental arch form using a preadjusted appliance with premolar extraction in Class I crowding. Angle Orthod 78(6): 1043-1049.

- Ward DE, Workman J, Brown R, Richmond S. Changes in arch width. A 20-year longitudinal study of orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 76(1): 6-13.

- Tajik I, Mushtaq N, Khan M (2011) Arch forms among different Angle classification A – study. Pakistan Oral Dent J 31(1): 92-95.

- Paranhos LR, Andrews WA, Joias RP, Berzin F, Junior ED, et al. (2011) Dental arch morphology in normal occlusions. Braz J Oral Sci 10(1): 65-68.

- Olmez S, Dogan S (2011) Comparison of the arch forms and dimensions in various malocclusions of the Turkish population. Open J Stomatol 2011; 1: 158-164.

- Murshid ZA (2012) Patterns of dental arch form in the different classes of malocclusion. Journal of American Science 8(10): 308-312.

- Noroozi H, Nik TH, Saeeda R (2001) The Dental Arch Form Revisited. Angle Orthod 71(5): 386–389.

- Owais AI, Abu Alhaija ES, Oweis RR, Al Khateeb SN (2014) Maxillary and mandibular arch forms in the primary dentition stage. Oral Health Dent Manag 13(2): 330-335.

- Chuck GC (1933) The ideal arch form. The Angle Orthodontist 3: 312- 327.

- Barrow GV, White JR (1952) Developmental changes of the maxillary and mandibular dental arches. Angle Orthod 22(1): 41-46.

- Braun S, Hnat WP, Fender DE, Legan HL (1998) The form of the human dental arch. The Angle Orthodontist 68(1): 29-36.

- Nojima K, McLaughlin RP, Isshiki Y, Sinclair PM (2001) A comparative study on Caucasian and Japanese mandibular clinical arch forms. Angle Orthod 71(3): 195-200.

- Sayin MO, Turkkahraman H (2004) Comparison of dental arch and alveolar widths of patients with class II, division 1 malocclusion and subjects with class I ideal occlusion. Angle Orthod 74(3): 356-360.

- Uysal T, Memili B, Usumez S, Sari Z (2005) Dental and alveolar arch widths in normal occlusion, class II division 1 and Class II division 2 malocclusion. Angle Orthod 75(6): 941-947.

- Uysal T, Usumez S, Memili B, Sari Z (2005) Dental and alveolar arch widths in normal occlusion and Class III malocclusion. Angle Orthod 75(5): 809-813.

- Khatri JM, Maadan JB (2012) Evaluation of arch form among patients seeking orthodontic treatment. J Ind Orthod Soc 46(4): 325-328.

- Henrikson J, Persson M, Thailander B (2001) Long-term stability of dental arch form in normal occlusion from 13-31 years of age. Eur J Orthodont 23(1): 51-61.

- Louly F, Nouer PR, Janson G, Pinzan A (2011) Dental arch dimensions in the mixed dentition: a study of Brazilian children from 9 to 12 years of age. J Appl Oral Sci 19(2): 169-174.

- Nakatsuka M, Iwai Y, Huang ST, Huang HC, Kon HI, et al. (2011) Cluster analysis of maxillary dental arch forms. The Taiwan J Oral Med Sci 27: 66-81.

- Beazley WM (1971) Assessment of mandibular arch length discrepancy utilizing an individualized arch form. Angle Orthod 41(1): 45-54.

- Goldstein G, Kapadia Y, Lin TY, Zhivago P (2015) The catenary curve: A guide to mandibular arch form. Periodon Prosthodon 1: 1.

- Mutinelli S, Manfredi M, Cozzani M (2000) A mathematic-geometric model to calculate variation in mandibular arch form. Eur J Orthod 22: 113-125.

- Shrestha RM (2013) Polynomial analysis of dental arch form of Nepalese adult subjects. Orthod J Nepal 3(1): 7-13.

- Burris BG, Harris EF (2000) Maxillary arch size and shape in American blacks and whites. Angle Orthod 70(4): 297-302.

- Cassidy KM, Harris EF, Tolley EA, Keim RG (1998) Genetic influence on dental arch form in orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod 68(5): 445-454.

- Slaj M, Jezina MA, Lauc T, Mestrovic SR, Miksic M (2003) Longitudinal dental arch changes in the mixed dentition. Angle Orthod 73(5): 509– 514.

- AlHarbi S, Alkofide EA, AlMadi A (2008) Mathematical Analyses of Dental Arch Curvature in Normal Occlusion. Angle Orthod 78(2): 281- 287.

- Anwar N, Fida M (2010) Variability of arch forms in various vertical facial patterns. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 20(9): 565-570.

- Othman SA, Xinwei ES, Lim SY, Jamaludin M, Mohamed NH, et al. (2012) Comparison of arch form between ethnic Malays and Malaysian aborigines in Peninsular Malaysia. Korean J Orthod 42(1): 47-54.

- Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder J, Nowak A (1997) Arch width changes from 6 weeks to 45 years of age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 111(4): 401-409.

- Zhou L, Mok CW, Hagg U, McGrath C, Bendeus M, et al. (2008) Anteroposterior dental arch and jaw-base relationships in a population sample. Angle Orthod 78 (6): 1023-1029.

- Isik F, Sayinsu K, Nalbantgil D, Arun T (2005) A comparative study of dental arch widths: extraction and non-extraction treatment. Eur J Orthod 27(6): 585-589.

- Iseri H, Tekkaya AE, Oztan O, Bilgic S (1998) Biomechanical effects of rapid maxillary expansion on the craniofacial skeleton, studied by finite element method. Eur J Orthod 20(4): 347-356.

- Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Miani A, Tartaglia G (1994) Mathematical definition of the shape of dental arches in human permanent healthy dentitions. Eur J Orthod 16(4): 287-294.

- Ackerman M B, Ackerman JL (2002) Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod 36(4): 221-236.