Abstract

Lesotho, like other developing nations, faces common financial inclusion barriers, such as physical presence, which impacts accessibility, affordability, and account opening processes. This study explores the link between educational attainment and financial inclusion in Lesotho. We analyse data from 1991 to 2022 and find a surprising result: while primary education has a positive long-run impact on financial inclusion, secondary and tertiary education show a negative long-run impact on financial inclusion, albeit insignificant, relationship. This counterintuitive finding suggests a need for further investigation into the role of financial literacy and tailored interventions to promote financial inclusion across all education levels in Lesotho.

Keywords:Financial inclusion; Educational attainment; Financial literacy; ADRL model; Lesotho

Abbreviations:FI: Financial inclusion; NSPD: National Strategic Development Plan; GoL: Government of Lesotho; MoFD: Ministry of Finance and Development; Inf: Inflation; ADF: Augmented Dickey-Fuller; ARDL: Autoregressive Distributed Lag model

Introduction

There is a need for sustainable financial inclusion, which is crucial in boosting economic growth as well as social wealth (Blach, 2011). One benefit of financial inclusion (FI) is that it makes it easier to allocate critical resources, reducing the cost of capital efficiently. The second benefit is access to the appropriate and necessary financial services to better the management of funds daily. The third benefit is the helpful role of reducing the increment of informal sources of loan facilities such as moneylenders who often are presented as being exploitive Sarma [1]. Banking stability and economic sustainability can be much archived if inclusive finance is ensured. A sample of Asian countries between the years 2004 and 2016 Li, Wu, & Xiao [2] found that FI positively influences financial sustainability. Neaime and Gaysset [3] also carried out an empirical study of MENA countries, the study gets across the relations between FI and bank growth and stability of the banking sector. Ahamed & Mallick (2019) also report the significant impact of FI on bank stability.

According to the Lesotho FinScope Survey [4], 81 % of the adult population is financially included, which is significantly higher than in other countries where FinScope has surveyed. For instance, the Eswatini FinScope [4], survey recorded 62.5 % financial inclusion, the Malawi FinScope [5] survey recorded 51 % financial inclusion, and the Mozambique FinScope [6] survey reported 39.6 % financial inclusion. The main driver behind the high level of financial inclusion in Lesotho is the use of insurance funeral cover. Many households with funeral covers do not have bank accounts and do not access banking financial services such as savings, loans, and money transfers and payments hence the Fin Scope survey reported only 38% of bank account ownership. (Demirguc-Kunt et al. (2018) using the Global Findex Database (2017) found that the account ownership percentage has increased from 38 percent reported by the 2011 FinScope survey to 46 % in 2017.

As reported by Jefferis & Manje [7], there are only four licensed banks in Lesotho. This includes Standard Lesotho Bank, NetBank Lesotho, First National Bank, Lesotho, and Lesotho Postbank. Three of these banks, FNB, Nedbank, and SLB are subsidiaries of South African banks. In terms of the bank size, as measured by the loan book and customer base, SLB is the largest commercial bank in Lesotho Sekantsi & Motelle [8]. They control a more significant proportion of the market within the financial sector of Lesotho, with total assets amounting to close to 42.3% of the GDP. These commercial banks provide access to financial services through branch networks and electronic channels such as automated teller machines, point-of-sale terminals, internet banking, and mobile banking. It was also reported that there are about eight creditsonly microfinance institutions with a significant growth observed at Letshego among the eight. The country has multiple savings and credit cooperatives (SACCOs), however, only the Boliba savings and credit cooperative society operates on a relatively large scale. In addition to licensed financial institutions, there are other financial services providers such as formal moneylenders, mobile network operators through mobile money, Shoprite cross-border money remittance, and savings and credit cooperatives (SACCOs).

One aspect of education that is essential for financial inclusion is financial education/literacy. According to Child and Youth Finance International OCED [9], financial literacy is a broad concept, encompassing people’s knowledge and skills to appreciate their financial circumstances, coupled with the willingness to make an informed choice. Financial education or literacy in this context is defined as learning about financial products and services and then using the skills and knowledge more broadly in the economy. It is reasonable to believe that a certain minimum level of education is required for an individual to gain a basic understanding of financial products.

Reports indicate that Lesotho Post Bank launched a mobile wallet service, Khetsi, in 2019. The services were made available to both Vodacom and Econet. This included withdrawals, utility payments, and community loans and savings. Khetsi started operations as a mobile virtual wallet that held payment card information. The bank was recorded as the most notable in serving rural and urban Basotho unbanked or underbanked. First National Bank of Lesotho launched a new channel named Cash Plus Lai-Lai in March 2019, intended to foster financial inclusion and bring banking services to consumers across the country. Lai-Lai is a mobile banking facility through which FNB provides withdrawal and deposit services to consumers using Lai- Lai agents as an alternative service channel. These agents are the bank’s cash-heavy clients with high frequency of cash deposits.

Financial inclusion in Lesotho is a key policy objective and forms part of the 2012, National Strategic Development Plan (NSDP) [10]. The Government of Lesotho (GoL) is committed to continuing to grow and support policies that promote financial inclusion in Lesotho and recognizes financial inclusion as one of the means of poverty alleviation. The commitment to the course is evidenced by the dedicated Inclusive (Finance Strategy of Lesotho, 2012), driven by the Ministry of Finance and Development (MoFD). The strategy aims are to expand access to credit, savings, and other financial services with the end goal of employment creation, poverty alleviation, improved access to health and education, and reduced risks and vulnerability for the financially excluded population. The Government continues to make strides to promote financial inclusion, leveraging on the partnerships, and loping in the private sector. In partnership with the CBL, FinMark Trust, and the UNDP, the Ministry of Finance has marked 29 November as a financial inclusion day, as a way of emphasising the importance of financial inclusion in the ministry agenda.

There is broad consensus within the development sector that financial inclusion is one of the channels through which poverty can be reduced Aguera [11]. This is premised on the belief that it improves livelihoods because it has causal effects Lyman, Demirguc-Kunt, & Cull [12]. According to the (NSDP) National Strategic Development Plan (2012), the main factor that hinders financial inclusion in Lesotho is the lack of financial knowledge. According to Maliehe [13] in the study of demand for mobile money among the rural and low-income population in Lesotho, many people in Lesotho, especially the poor people in rural areas where it is not commercially viable to open bank branches, are financially excluded.

A sizable portion of the population has restricted access to the established financial industry. Taking into account that the majority of people in Lesotho are employed in the informal economy in both rural and urban regions and agriculture, the banks and insurance firms, with their branch network, which is mostly centred in cities, are unable to efficiently mobilize savings in rural areas and extend financing, especially to small and medium-sized businesses and the agricultural sector operators. The lack of MFIs accepting deposits and the development of inclusive finance has been further hampered by the absence of robust financial cooperatives in Lesotho.

The purpose of this study is to assess the role played by educational attainment in expanding financial inclusion in Lesotho in line with the Government’s key policy to achieve healthy financial inclusion and access in Lesotho. The existing studies of the relationship between educational attainment and financial inclusion in Lesotho do not show the impulse response of the financial inclusion rate to the shocks on educational attainment variables. While seeking to close this gap, the study shall provide new knowledge to the available value of this study and add to the literature that already exists on financial inclusion and educational attainment in Lesotho. It will also inform the policymakers and regulators in terms of sound financial decisionmaking. An understanding of the role banks play in the country’s financial inclusion would help banks make better decisions that would improve the financial performance of the financial institutions. The remaining sections of this paper proceed as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the literature on the subject matter. Section 3 describes the data and offers some preliminary analysis. Section 4 presents the methodology. Section 5 presents the empirical results and discusses the findings, while Section 6 concludes the paper.

Brief Literature Review

Barriers to owning a conventional bank account and the need to increase participation in the financial system and reduce social inequalities associated with financial exclusion call for a study on the role educational attainment can play in advancing the financial inclusion objective. This section of the paper, therefore, intends to Review some Literature and some that have appreciated the concept of education as a tool for the enhancement of financial inclusion while also considering the empirical evidence relevant to our paper. The financial literacy theory of financial inclusion, states that raising citizens’ financial literacy levels through education is one way to attain financial inclusion. This theory argues that people will be more inclined to participate in the formal financial sector if they are financially literate. There are benefits to the financial literacy theory. One, financial literacy can make consumers conscious of the financial products and services that are obtainable. When individuals become aware of existing financial products and services that can enhance their welfare, they are more willing to engage in the formal financial sector by possessing a bank account. Second, by becoming more financially literate, people can benefit from additional services provided by the official financial industry, like mortgage and investment products. Thirdly, by teaching people to save money so they can pay their bills on time, and retirement plan, and help them differentiate between needs and wants, financial literacy can also assist individuals in becoming more self-sufficient and having some stability in their finances.

Sangyoon [14] analysed results of the IV model showing the effect of compulsory upper-secondary education on financial inclusion using cross-country data from the World Bank, United Nations development program and International Monetary Fund. The findings showed that in exception of those 60 years of age or older, compulsory upper-secondary education improved financial inclusion across the board for all socioeconomic groups. For women, compulsory upper-secondary education had the greatest effect on financial inclusion. In contrast, we discovered that while some groups required completing their upper-secondary education at the very least, completing lower-secondary education was efficient in promoting financial inclusion in the high-income class.

On the other hand, Sangyoon [14] assumed that the required level of education differs for each sociodemographic characteristic and hence performed the same model with the dependent variable of the lower-secondary variable instead of upper-secondary education. Except for the high-income class, compulsory lower secondary education did not significantly correlate with financial inclusion according to the OLS model. In the high-income class, compulsory lower-secondary education and account ownership rates were significantly positive (b = 7.732, p = 0.054). As a result, the IV model might be used to examine the impact of lower secondary education on financial education in the high-income class. Compulsory lower-secondary education increased the rate of account ownership in the high-income class by approximately 35%, this suggests that compulsory lower-secondary education could help the high-income class to promote financial inclusion.

Using their main source of data the 2015 Kenya Fin Access household survey Ajayi and Ross [15] presented the reduced-form impacts of free primary education on financial inclusion, financial capability, and economic self-sufficiency using the difference in difference specification. Their findings showed that education primarily increased financial inclusion by raising labour earnings; with little direct impact on financial capability, furthermore, the results suggested that digital financial services could be an essential addition to education in efforts to improve the financial outcomes of youth.

In a related study in South Africa, Mishi et al. [16] assessed the way how literacy levels related to and impacted access to banks in South Africa, focusing on the Eastern Cape Province. Survey questionnaires were distributed to three local municipalities in the Eastern Cape, namely Peddie, Willow Vale (Idutywa) and Cholumna. There have been numerous financial literacy programs primarily aimed at the youth, women and students in these areas. The focus was on testing the impact of literacy level on access to banking. The study found that the level of literacy was significantly and positively correlated to access to banking by individuals, with as much impact coming from literacy as measured by the ability to read English.

Nuryasman & Vincent [17] conducted a study to investigate the impact of financial literacy and financial inclusion on students of the Faculty of Economics at Tarumanagara University. Stratified random sampling was used and questionnaires involving 472 respondents were drafted. Meanwhile, the data analysis technique used was logistic regression analysis, with the z-statistic test, F-test, and McFadden R-Square. According to the results of hypothesis testing, financial literacy is significantly influenced by age, while gender, education, investment experience, academic ability, and residence status have no significant effect on financial literacy. Other findings were that financial literacy and income have a significant effect on financial inclusiveness, while financial information sources, proximity to banks, and ownership of vehicles have no pronounced impacts.

Data and Preliminary Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

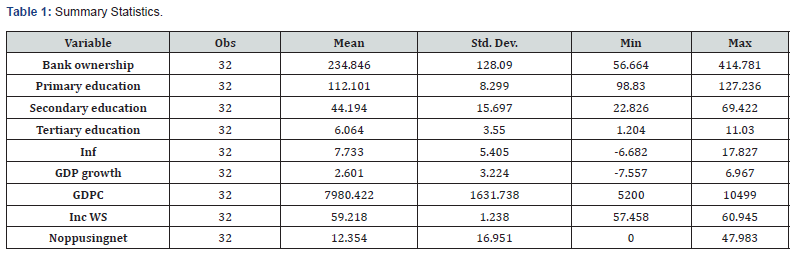

Table 1 presents the summary statistics for nine variables: primary education, secondary education, tertiary education, Inflation (inf), GDP growth, GDP per capita (GDPC), Income Wages and salaries (IncWS), Number of People using Internet (Noppusingnet). Throughout the period from 1991 to 2022, bank ownership in Lesotho consistently exceeded the general benchmark of approximately 57%. The standard deviation remained within the expected range. The aggregate level of primary education hovered around 112.101, with a maximum value of 127.236 and a standard deviation of 8.299, falling below the minimum range of 98.83. Similarly, the aggregate level of secondary education was 44.194, reaching a maximum of 69.422, with a standard deviation of 15.697 falling outside the expected range. Furthermore, the aggregate level of tertiary education was 6.064, reaching a maximum of 11.03, with a standard deviation of 3.55, notably lower than the expected range. Notably, the means of all variables fell within the expected range, indicating a high level of consistency. However, the standard deviations of all explanatory variables were notably lower than the expected range, suggesting minimal variance and unbiased results.

Note: For the purpose of summary statistics, the variables are expressed in their level form. For instance, bank ownership as a measure of Financial Inclusion, Primary is when an individual has a primary level of education, Secondary is when an individual has a secondary level of education, Tertiary is when an individual has a tertiary level of education, GDP per capita measured by the economic growth rate, GDP per capita measured by the economic growth rate, Income measured by wages and salaries, Technology proxied by internet access (number of people using the internet) respectively. More so, the terms Std. dev. is the standard deviation, Min and Max denote the minimum and maximum values, while Obs. is the number of observations.

Note: bank ownership as a measure of Financial Inclusion. Primary is when an individual has a primary level of education, Secondary is when an individual has a secondary level of education, Tertiary is when an individual has a tertiary level of education. GDP per capita measured by the economic growth rate, GDP per capita measured by the economic growth rate, Income measured by wages and salaries, Technology proxied by internet access (number of people using the internet) respectively.

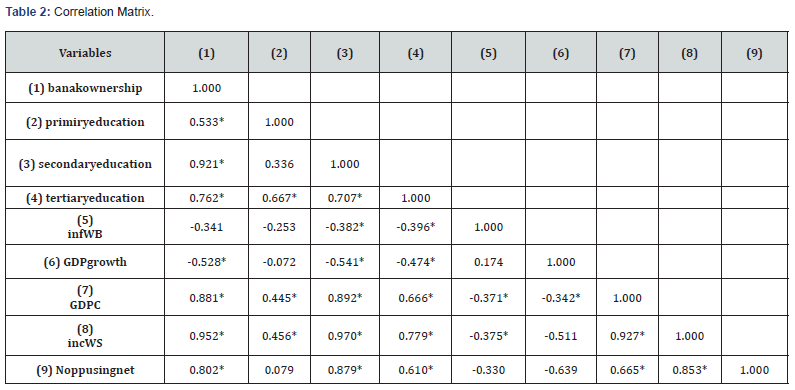

In furthering the analysis of the descriptive statistics, the correlation matrix is presented in Table 2 to assess the degree of collinearity between the independent variables. The matrix shows that multi-collinearity is no serious issue since the key independent variables primary education, secondary education, and tertiary education are almost independent of all control variables. Furthermore, there exists no perfect relationship between all the included variables.

The matrix shows that there is a moderate positive relationship (0.533) between primary education and financial inclusion (bank ownership). On the other hand, there is a high positive relationship between secondary (0.921), tertiary education (0.762) and financial inclusion. The relationship between inflation (-0.341), GDP growth (-0.528) and financial inclusion. Lastly, there is a high relationship between GDP per capita (0.881), income (0.952), number of people using the internet (0.802) and financial inclusion.

The unit root test for stationarity

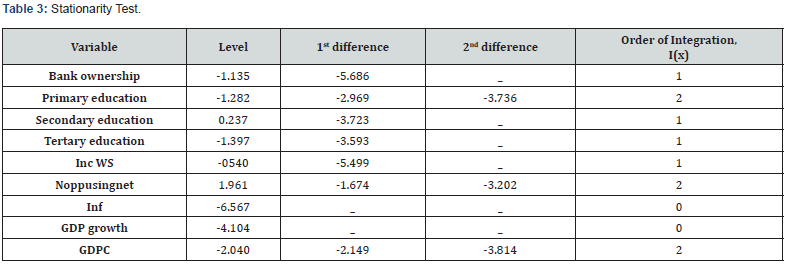

To begin the estimation process, time series data, examined first for Stationarity in Table 3. It becomes imperative that a unit root test be conducted as stationarity is an important characteristic in a time series analysis. A time-series process is said to be covariance stationary (or weakly stationary) if its mean and variance are constant and independent of time and the covariance depends only upon the distance between two periods, but not the periods per se. If a time series process is non-stationary, then the results can be unreliable and spurious (high R2 yet there is little or no correlation). This would make forecasting both in the short run and long run impractical as the study would be limited to the behavioural patterns under the period considered only

The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test will be utilized to deduce the number of unit roots (if any) or non-stationarity of the variables and to cater for serial autocorrelation in their errors. The null hypothesis (H0) of the presence of a unit root is tested against the alternative hypothesis (H1) of no root. The decision criterion will be to reject the null hypothesis if the calculated t-statistics is less than the Dickey-Fuller critical value, which will imply that the variable is stationary.

Summarily, according to the results reported in Table 3, we found that financial inclusion (bank ownership), secondary education (secondaryeducation), tertiary education (tertiaryeducation) and income wage levels (incWS) are integrated of order 1 or I (1) which implies they are stationary at the first difference, while inflation (inf) and GDP growth (GDPgrowth) are integrated of order 0 or I (0) meaning it is stationary at levels. However, primary education (primaryeducation), GDP per capita (GDPC) and technology (Noppusingnet) are integrated of order 2 or I (2) implying that they are stationary at the second difference. On this account, the Autoregressive Distributed Lag model (ARDL) is employed.

Cointegration test

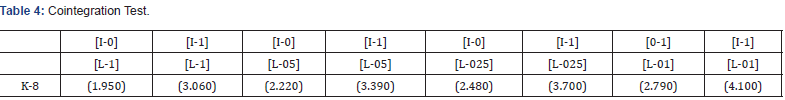

The Table 4 summarizes the cointegration test results

and to test for cointegration, we will test the following

hypotheses:

H0:no levels relationship

H1: levels relationship

The decision rule is to reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration in favour of the alternative hypothesis if the F-statistic is greater than all the critical upper bound values for I (1) regressors.

From the results in Table 4, the decision is to reject the null hypothesis since the F calculated (F=10.362) is greater than the F critical (1.950, 3.060, 2.220, 3.390, 2.480, 3.700, 2.790 and 4.100) and conclude there is co-integration. We then proceed to estimate the long run effects and the short run effects, which now include an error correction term.

Methodology

Introduction

This chapter describes the methodology used in this study. The methodology is selected to analyse the relationship between educational attainment and Financial Inclusion (FI) in Lesotho. It is organised as follows: Discusses the data and sources, the theoretical framework, the model specification, and finally discuss methods of data analysis and estimating techniques.

Data Sources

Secondary data is used in this study to answer our research question, collected from the World Bank and UNESCO. We collect time series data covering the period 1991 to 2022(on an annual basis) providing a total of 32 observations in Lesotho. We collect time series data because it is superior to cross-sectional one and it captures the relationship between multiple quantities as they change over time. The data is collected from various variables including financial inclusion, educational attainment, inflation, income, GDP per capita and technology.

Theoretical Framework

We base our model on the theory of financial literacy of financial inclusion which states that raising citizen’s financial literacy skills through education is one approach to attaining financial inclusion. This idea states that financial literacy will increase an individual’s propensity to interact with the formal financial sector. The principle of financial literacy has advantages, one, financial literacy helps by educating customers about the financial services and products that are accessible to them. People will be more inclined to join the formal financial sector by owning a bank account once they are aware of the financial products and services that are already available and can enhance their well-being. Second, people can gain access to more services offered by the official financial industry, such as investment and mortgage products, by developing their financial literacy. Thirdly, financial literacy may help people to become self–sufficient and have some stability in their finances by teaching them how to save money so they can plan for retirement, pay their bills on time, and learn to distinguish between necessities and wants. Lastly, governments with limited resources, public or tax may decide to employ financial literacy as a national financial inclusion strategy because it does not cost a lot of money to teach the people how to use formal financial services.

Model Specification

To provide an elaborate analysis, we adopt the model of

Mzobe [18] where the role of education and financial inclusion in

Africa was investigated. Our study, however, adjusts her model by

disaggregating educational attainment into not only primary and

secondary education but we also account for tertiary education in

our model. Our model also accounts for the effect of GDP per capita,

income wages and salaries, technology, GDP growth and inflation

to account for affordability, accessibility and the standard of living

which are in alignment with the concepts associated with our

theoretical framework (financial literacy of financial inclusion).

The model specifies financial inclusion (FI) as a function of several

explanatory variables. The empirical model is as follows:

FI = f (Primary education, Secondary education, tertiary

education, Inflation, income,

GDP Per Capita, technology) (1)

The model can be econometrically stated as follows:

log FIt = β0 + β1Secondaryt + β2Primaryt + β3Tertiaryt + β4 Inflationt + β5 Incomet + β6 GDP per capitat + β7Technologyt + εt (2)

Where:

FI is measured by bank ownership at time t

Primary is when an individual has a primary level of education

at time t

Secondary is when an individual has a secondary level of

education at time t

Tertiary is when an individual has a tertiary level of education

at time t

GDP per capita is measured by the economic growth rate at

time t

Inflation is measured by the GDP deflator at time t

Income is measured by wages and salaries at time t

Technology is proxied by internet access (number of people

using the internet) at time t

Estimation Techniques

To start the estimation of the time series data generated for the study, the Autoregressive Distributed Lag method for multiple regressions is employed. This method of analysis is employed because some of the variables are most likely to be stationary at the level while some of them may be stationary at first difference as they tend to fluctuate over time rather than remain constant and predictable. It will help to determine the long-run and shortrun relationship between the variables. Furthermore, the post– estimation external validity tests will be carried out to ensure the goodness of fit of the model. The tests that will be used to inspect the serial correlation and normality related to the model comprise the stability, normality, autocorrelation, and heteroscedasticity tests. Descriptive statistics of the data will also be carried out. The data will then be estimated using the ordinary least square to reveal signs, the value of the coefficients and the probability values to determine the significance levels.

Empirical Results

Note: Bank ownership as a measure of Financial Inclusion, Primary is when an individual has a primary level of education, Secondary is when an individual has a secondary level of education, Tertiary is when an individual has a tertiary level of education, GDP per capita measured by the economic growth rate, GDP per capita measured by the economic growth rate, Income measured by wages and salaries, Technology proxied by internet access (number of people using the internet) respectively.

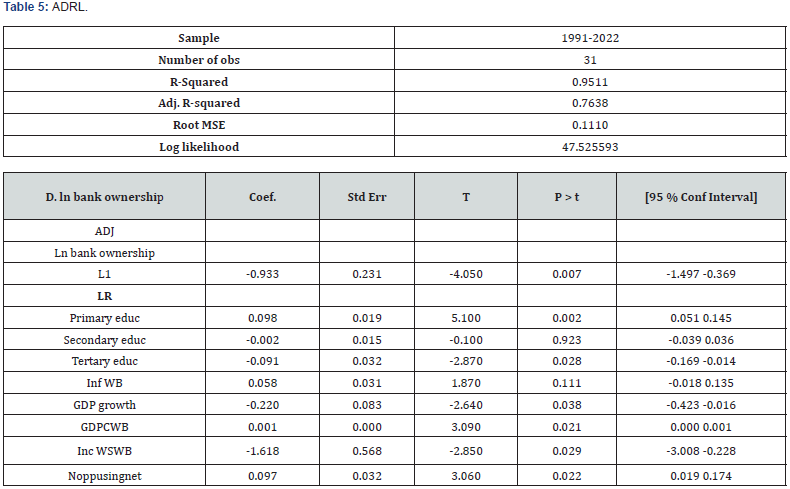

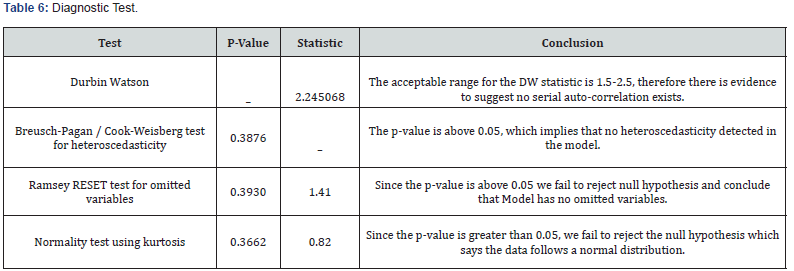

To ascertain the impact of educational attainment on financial inclusion in Lesotho, this study employed the ARDL model. To use this model, the study first checked the variables for stationarity using the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, after confirming the different orders of integration in Table 3, the study proceeded to estimate the ARDL Bounds Cointegration test as shown in Table 4. The study then estimates the ARDL as shown in Table 5. The outcome of the diagnostics test infers that there exists no serial autocorrelation (Durbin-Watson test), no heteroscedasticity (Breusch-Pagan test) and no omitted variables (Ramsey RESET test).

F = 10.362

Note: F-calculated is 10.362 and F-tabulated are parentheses. K-8 denotes eight explanatory variables which are Primary education, Secondary

education, Tertiary education, Inflation, GDP growth, GDP per Capita, income and Number of People using Internet respectively.

Table 5, depicting the long-run model shows that there exists a positive relationship between financial inclusion (bankownership) and primary education, implying a one-year increase in primary education increases financial inclusion by 9.80 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, and it is significant at 5% significance level. Also, there is a negative relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and secondary education, which means a one-year increase in secondary education decreases financial inclusion by 0.15 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, even though it is not significant at a 5% significance level.

A negative relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and tertiary education exists, which means a oneyear increase in tertiary education decreases financial inclusion by 3.18 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, and it is significant at a 5% significance level. We also analysed a positive relationship between financial inclusion (bank account ownership) and inflation (inf), which implies a one-unit increase in inflation increases financial inclusion by 5.83 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, however, it is not significant at a 5% significance level.

There is a negative relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and GDP growth, which means a one-unit increase in GDP growth decreases financial inclusion by 21.97 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, it is significant at a 5% significance level. There is a positive relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and GDP per capita (GDPC), which means a one-unit increase in GDP per capita (GDPC), increases financial inclusion by 0.08 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, it is significant at a 5% significance level.

There exists a negative relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and income wage levels (incWS), which means a one-unit increase in income wage levels (incWS), decreases financial inclusion by 161.79 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, it is significant at a 5% significance level. Moreover, there is a positive relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and technology (Noppusingnet). When an additional person has access to technology (uses the internet) it leads to an increase in financial inclusion by 9.68 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, it is significant at a 5% significance level.

The results of the short run model suggest that there exists a negative relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and primary education, implying a one-year increase in primary education decreases financial inclusion by 5.64 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, and it is significant at a 5% significance level.

Also, there is a positive relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and secondary education, which means a oneyear increase in secondary education increases financial inclusion by 6.34 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, even though it is not significant at a 5% significance level.

A positive relationship between financial inclusion (bankownership) and tertiary education exists, which means a one-year increase in tertiary education decreases financial inclusion by 0.07 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, and it is not significant at a 5% significance level. We also analysed a negative relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and inflation (inf), which implies a one-unit increase in inflation decreases financial inclusion by 3.59 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, however, it is significant at a 5% significance level.

There is a positive relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and GDP growth, which means a one-unit increase in GDP growth increases financial inclusion by 96.18 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, however not significant at a 5% significance level. Again, there is a positive relationship between financial inclusion (bank ownership) and GDP per capita (GDPC), which means a one-unit increase in GDP per capita (GDPC), increases financial inclusion by 0.03 percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, it is not significant at a 5% significance level.

There exists a positive relationship between financial

inclusion (bank ownership) and income wage levels (incWS),

which means a one-unit increase in income wage levels (incWS),

increases financial inclusion by 97.53 percentage points on

average and ceteris paribus, it is significant at a 5% significance

level. Moreover, there is a negative relationship between financial

inclusion (bank ownership) and technology (Noppusingnet).

When an additional person has access to technology (uses the

internet) it leads to a decrease in financial inclusion by 4.10

percentage points on average and ceteris paribus, even though it

is not significant at a 5% significance level.

ARDL Regression Results: Table 5 ADRL

Post-Estimation Diagnostic Test: Table 6

Note: The term coef is coefficient, std Err is standard error, T and P denotes T-statistic and P-value respectively while “***, “**” and “*” symbolizes statistical significance respectively at 1%, 5% and 10 %.

Note: We reject null hypothesis if P-value is less than standard significance level (5%).

Conclusion

Introduction

This chapter covers the summary of the study, the key findings, and recommendations for policies. The study sought to examine the effect of educational attainment on financial inclusion in Lesotho while controlling for inflation, GDP per capita, GDP growth, technology and income wages and salaries. We adopted an ARDL model which examines both the short-run and the long-run. We considered a time series of data ranging from 1991 to 2022 on a yearly. To provide a more elaborate analysis, we also conducted several tests like the unit root test and some diagnostics like the Breusch-Pagan test for heteroscedasticity.

Summary of the Results and Conclusions

While seeking to find if educational attainment is a crucial tool for the Government to drive its financial inclusion agenda, financial inclusion was measured using bank account ownership as it is a reliable proxy because it reflects the presence of accessibility of formal financial products such as loans, savings and deposit accounts. Thus, bank account ownership serves as a key indicator of the degree to which people interact with a formal financial system, which is a fundamental aspect of financial inclusion. Educational attainment was disaggregated into primary, secondary and tertiary levels of education. In a nutshell, the study indicates that different levels of educational attainment have conflicting impacts on financial inclusion in Lesotho. In establishing a more elaborate relationship between the two variables of interest, stationarity was an interesting concept to uncover since the type of data that was used was time series, some variables were found to be stationary at first difference I (1), second difference I (2) while others were stationary at level I (0).

In the short-run, the model indicates a negative relationship between financial inclusion and primary education, while there exists a positive relationship between financial inclusion and secondary education. The short-run model also suggests a positive relationship between financial inclusion and tertiary education even though the relation is not significant. However, the long-run model indicates that there is a positive relationship between financial inclusion and primary education. While contrary to our prior expectations, there is a negative relationship between financial inclusion and secondary education. The negative relationship between tertiary education and financial inclusion, however, is not significant in the long-run. Despite some contradictory results between short-run and long-run regressions, both models point to the fact that indeed there is a significant relationship between educational attainment and financial inclusion.

Our empirical results pointed out that in the long-run primary education is positively related to financial inclusion and it is in line with Mzobe [18]. His study found that after controlling for other factors that equally influence financial inclusion, primary education has a positive and statistically significant effect on financial inclusion. On the other hand, our findings are in line with Bakshi and Agarwal [19] who found that both secondary and tertiary level of education plays a crucial role in financial inclusion as people with secondary and tertiary education open and maintain more accounts, more savings, more borrowing and internet payments. Our results are therefore in collaboration with our theoretical framework which stated a positive relationship between educational attainment and financial inclusion [20-24].

Policy Recommendations

These results are of paramount importance for several reasons. Schools should strengthen financial literacy programs, that is, at the primary education level they ought to introduce and enhance financial literacy programs as part of the standard curriculum. This can help create a foundation for good financial habits and understanding from an early age. The policymakers should encourage the private sector to build more primary schools in rural areas that are composed mostly of marginalised and illiterate people thereby increasing the enrolment rate at the primary level thus increasing financial inclusion in Lesotho as more bank accounts will be opened. We believe that secondary and tertiary levels of education are worsening the current state of financial inclusion in Lesotho due to an outdated and traditional curriculum therefore to curb this problem, the secondary and tertiary curriculum should be revamped, reviewed and updated at these levels to include practical financial education. This can be done by including subjects related to personal finance, financial management, monetary economics and entrepreneurship. Moreover, Commercial banks in Lesotho should expand their branches, especially in rural and isolated areas, this will resolve the problem of limited banking infrastructure by allowing the previously unbanked and under-banked sections of both secondary and tertiary students to access financial services. This could serve as a breakthrough for these students to build accounts history that would consequently help them to open formal bank accounts with the banking sector in Lesotho. Therefore, policymakers in Lesotho should promote and facilitate technology and its related financial services. Lastly, Policymakers should again pursue policies aimed to enhance growth. These policies are likely to result in enhanced financial inclusion in the country.

References

- Sarma M (2012) Index of Financial Inclusion - Ameasure of financial sector inclusiveness. Working Paper.

- Li J, Wu Y, Xiao JJ (2020) The impact of gigital finance oh household consumption: Evidence from China. Economic Modelling 86: 317-326.

- Neaime S, Gaysset I (2018) Financial inclusion and stability in MENE: Evidence from poverty and inequality. Finance Research Letters 24(C): 230-237.

- Lesotho Fin Scope Survey (2011) Fin Scope Consumer Survey Lesotho.

- Malawi Fin Scope (2014) FinScope consumer survey Malawi 2014. Fin Mark Trust.

- Mozambique FinScope (2014) FinScope Consumer Survey Mozambique 2014. Fin Mark Trust.

- Jefferis K, Manje L (2015) Making Access Possible: Lesotho Country Diagonostic Report. A Report Commissioned by Fin Mark Trust, Centre for Financial Regulation and United National Capital Development Fund.

- Sekantsi LP, Motelle SI (2016) The Financial Inclusion Conundrum in Lesotho: Is Mobile Money the Missing Piece in the Puzzle? Working paper p. 1-40.

- OCED (2012) Financial Education and Inclusion. Child And Youth Finance International. Madrid: 0ECD p. 1-14.

- National Strategic Development Plan (2012) Growth and Development Strategic Framework. Maseru: Lesoth government, ministry of development planning.

- Aguera P (2015) Financial Inclusion. Growth And Poverty Reduction p. 1-19.

- Lyman T, Demirguc-Kunt A, Cull R (2012) Financial Inclusion and Stability: What Does Research Show?

- Maliehe MS (2018) Demand for mobile money among the rural and the low population in Lesotho, Maseru.

- Sangyoon Y (2023) Effects of Compulsory Upper-Secondary Education on Financial Inclusion. Research Square p. 1-20.

- Ajayi KF, Ross PH (2017) The Effects of Education on Financial Outcomes: Evidence from Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change p. 1-53.

- Mishi S, Vacu PN, Chipote P (2012) Impact of financial literacy in optimising financial inclusion in rural South Africa: Case study of the Eastern Cape Province. Economic research Southern Africa.

- Nuryasman NM, Vincent (2018) Impact of Financial Literacy on Financial Inclusion. International Conference on Enterpreneurship and Business Management p. 26-31.

- Mzobe N (2015) The role of education and financial inclusion in Africa: The case of selected African countries p. 1-59.

- Bakshi D, Agarwal D (2020) Impact of Education on Financial inclusion: Study for India. Journal of Xi'an Univesity of Architecture and Technology XII(VII): 1-1179.

- Aydemir AB (2021) The impact of education on savings and financial behavior. Think Forward Initiative.

- Aydemir A, Kirdar M (2017) Low Wage Returns to Schooling in a Developing Country: Evidence from a Major Policy Reform in Turkey. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 79(6): 1046-1086.

- Aydemir A, Kırdar M, Torun H (2020) The effect of education on geographic mobility: Incidence, Timing and Type of Migration. Working paper.

- Eswatini Fin Scope (2011) Fins Scope Consumer Survey Swaziland 2011. Fin Mark Trust.

- UN (2006) Building inclusive financial sectors for development. New York: United Nations.