Comprehending the OSR Position of Panchayati Raj Institutions and its Sustainability in Assam, India

Anulekha Bhagawati*

PhD Research Scholar, Department of Management, North-Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Meghalaya

Submission: October 14, 2024; Published: November 06, 2024

*Corresponding author: Abhigyan Bhattacharjee, Professor & Head, Department of Management, North-Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Meghalaya

How to cite this article: Anulekha B. Comprehending the OSR Position of Panchayati Raj Institutions and its Sustainability in Assam, India. Acad J Politics and Public Admin. 2024; 2(1): 555577. DOI:10.19080/ACJPP.2024.02.555577.

Abstract

The goal of regional autonomy is to hasten regional development and economic growth, close social gaps, and enhance the efficiency and responsiveness of governmental services to the requirements, potentials, and features of the local populace. The expansion of financial basis of local self-governments (Panchayats in context of India) is crucial to the success of decentralization. However, it has come to light that the local government bodies are primarily answerable to the Central or States government and rely on grants from them, which disproves the concept of participatory democracy. According to estimates, the amount of economic development increases with how well own-source revenue is collected and utilized. The Ministry of Panchayati Raj’s meeting on “Local Bodies and State Finance Commission” in 2011 concluded that the best way to increase panchayat autonomy and accountability is to implement effective fiscal decentralization, ensure that the panchayats effectively exercise their powers, and generate their own revenue. However, rural local self-government bodies are not financially sustainable due to their limited resource base. This study aims to evaluate the status of local self-government bodies’ own source of income in the state of Assam, India. Based on data availability, a few PRIs were selected from the Bongaigaon and Cachar districts of Assam, representing the Brahmaputra and Barak valley of Assam, respectively. The study comprehends OSR’s situation over the five years period, from 2017–2018 to 2021–2022, and suggest a sustainable future road map for the local government bodies.

Keywords: OSR; decentralization; Sustainability; Autonomy; Local self-government bodies; Panchayat; Economic development

Introduction

Fiscal decentralization, in which government transfers funds or permits lower-level governments to raise their own money, is the central aspect of decentralization Munyua [1]. In India, fiscal decentralization to rural local governments only makes sense, provided the Panchayats have enough unrestricted cash to deliver the public services assigned to them, which calls for the delegation of taxing authority. Dependence on fiscal transfers could lower the ability of local governments to distribute resources following their objectives if the transfers are conditional and have a specified aim Rao & Rao [2]. Fiscal decentralization entails multiple tiers of government, each of which has its own set of expenditure duties and responsibilities and taxing authority Luiz & Bareinstein [3]. If a local government finances at least a portion of its budget from its resources, i.e., through local taxation, it will be more accountable administratively. If the local government only uses funds that have been given to it through vertical transfers, this incentive will be absent Jha [4].

The capacity of the rural economy and the willingness of rural families to pay taxes and make voluntary contributions to programs carried out by Panchayats are requirements for the Own Resource Mobilization of Panchayats. To adequately address the issue of own resources mobilization, political, sociological, and geographic factors must be taken into account Chakraborty [5].

Given that money generated is decided at the local level in accordance with the principle of fiscal federalism, it is reasonable to assume that own source revenue is an indicator of fiscal federalism Munyua [1].

Relevance of Own Source Revenue Mobilization in the Context of Panchayati Raj Institutions

The Assam Panchayat Act, 1994 has given the definition of own fund for Zilla Parishad, Anchalik Panchayat and Gaon Panchayat Zakir & Islam [6].

According to the Assam Panchayat Act of 1994, each Zilla Parishad must have a Zilla Parishad fund, which must include or receive the following contributions:

a) The amount transferred to the Zilla Parishad fund by appropriation form out of the consolidated fund of the State;

b) All grants, assignment, loans, and contributions made by the Government;

c) All fees and penalties paid to or levied by or on behalf of the Zilla Parishad under this Act and all fines imposed under this Act;

d) All rents from Land or other properties of the Zilla Parishad;

e) All interest, profits and other money acquired by gifts, grants, assignments, or transfers from private individuals or institutions;

f) All proceeds of lands, securities and other properties sold by the Zilla Parishad:

g) All sums received by or on behalf of the Zilla Parishad by virtue of this Act.

Provided that sums received by way of endowments for any specific purpose shall not form part of or be paid into Zilla Parishad

According to the Assam Panchayati Raj Act of 1994, a fund called the Anchalik Panchyat shall be established for each Anchalik Panchayat, and funds shall be deposited to its credit.

i. Contribution or grants, if any made by Central or State Government, including such part of the land revenue collected in the State as may be determined by the Government;

ii. Contribution and grant, if any made by the Zilla Parishad or any other local authority;

iii. Loans if any granted by the Central or the State Government or raised by Anchalik Panchayat on security of its assets;

iv. All receipts on account of tolls, rates and fees levied by it;

v. All receipts in respect of any schools, hospitals, dispensaries,buildings, institutions or work vested in , constructed by or placed under the control and management of Anchalik Panchayat;

vi. All sums received as gifts or contributions and all income from any trust or endowment made in favour of the Anchalik Panchayat;

vii. Such fines and penalties imposed and realized under the provisions of this Act, as may be prescribed, and all other sums received by or on behalf of the Anchalik Panchayat.

According to the Assam Panchayat Act of 1994, a Gaon Panchayat fund bearing the name of the Gaon Panchayat must be established for each one, and funds must be deposited to its credit.

a) Contribution or grants, if any made by Central or State Government;

b) Contribution and grant, if any made by the Zilla Parishad, Anchalik Panchayat or any other local authority;

c) Loans if any granted by the Central or the State Government;

d) All receipts on account of taxes, rates and fees levied by it;

e) All receipts in respect of any schools, hospitals, dispensary, buildings, institutions or work vested in, constructed by or placed under the control and management of the Gaon Panchayat;

f) All sums received as gifts or contributions and all income from any trust or endowment made in favour of the Gaon Panchayat;

g) Such fines and penalties imposed and realized under the provisions of this Act, as may be prescribed, and all other sums received by or on behalf of the Gaon Panchayat.

The different sources of tax revenue of the PRIs are-

1. Property tax; which include (a) tax on lands (lands not subject to agricultural assessment), (b) Tax on building- House tax (inclusive of land appurtenant to such buildings); 2. Profession tax; 3. Water tax; 4. Tax on entertainment; 5. Tax on vehicles; 6. Advertisement Tax; 7. Stamp duty; 8. Other taxes

The sources of Non-tax revenues are-

1. License Fee; 2. Rent; 3. Permit Fee; 4. Registration Fee; 5. Other Fees; 6. Penalties and Fines; 7. User Charges; 7. Income from investment and interest; 8. Sales and hire charges; 9. Market Receipts; 10. Royalties for minerals and others; 11. Others (e.g remunerative assets).

Literature Review

We looked at a few recent studies to shed more light on the relevance of the PRIs’ source of revenue and to assess the sustainability of the financial health of the PRIs.

Khadondi [8] investigated the variables of Own Source Revenue Mobilization by Kenyan Counties. His study examined urbanization, intergovernmental grants, poverty, and land area as independent variables and the own source revenue mobilization of counties in Kenya as the dependent variable. Among all other independent variables, urbanization levels had the most significant impact on own source revenue mobilization by counties. Palharya [9] explored how financial constraints hindered Madhya Pradesh’s decentralized governance. He determined that economic conditions and insufficient resource mobilization had significantly impeded the functioning of these institutions and that the changes brought about by the Constitutional Amendments were neither radical nor had far-reaching repercussions. Very little fiscal decentralization had occurred inside PRIs. The fiscal autonomy of these institutions was far from adequate, as they had virtually little fiscal authority and relied primarily on donations, most of which were attached to specific programs.

Coker & Adams [9] discovered, in examining the difficulties of managing local government finances in Nigeria, that local governments have a dwindling revenue base, lack autonomy in financial management, and are plagued by corruption, among others. They attributed the country’s poor financial condition to excessive reliance on intergovernmental transfers and tax evasion, resulting in decreased revenue collection to cover development and recurring costs. In addition, it was discovered that local governments in Nigeria lacked qualified personnel, had inadequate record-keeping and account management, were not held accountable for their funds, suffered from political influence, and lacked transparency and accountability.

Regarding fiscal devolution, Ratra & Dahiya [10] examined the difficulties Local-self-government in India faced. They contend that developing internal revenue streams is the most excellent method to increase the transparency, accountability, effectiveness, and independence of Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs).

Chepkoech [11] established the impact of e-services, mobile payment systems, and e-banking payment systems on sustainable revenue collection in the Nairobi County government in a cross-sectional research design-based study. They discovered that using e-services improves revenue collection; e-billing makes it easier for the County to collect revenue, and e-invoicing increases revenue sustainability. Munyua [1] made an effort to assess the impact of their own source revenue on the performance of Kenyan women-owned micro-businesses. According to the study’s findings, there is a marginally good correlation between County’s own-source revenue and micro-enterprise performance (R = 0.91 and p=0.012). Their investigation revealed that county governments use computerized tax collecting. Even though automating revenue collection may appear to be simpler than the manual technique of revenue collection, this study indicated that women entrepreneurs need help understanding the system, making it a burden for them.

Ma & Mao [12] looked at a radical fiscal decentralization reform in China to study the impact of fiscal decentralization on economic growth. They discovered that the fiscal decentralization reform could significantly increase the GDP growth rate by using the difference-in-differences (DID) technique to detect the consequences of the change. In a different study, Mbau [13] analyzed the impact of fiscal decentralization on the performance of County governments in Kenya for six years from 2013 to 2018. They used three measures of fiscal decentralization, including the proportion of county governments’ funding from the federal government to local tax collections, as well as transfer grants, defined as funds received from the federal government and development partners under both conditional and unconditional terms.

Research Gap

According to the literature assessment, there have been relatively few studies on rural local bodies. In contrast, there have been many more urban local bodies, such as counties or municipalities, both globally and in India. Though raising own-source money is a crucial responsibility, administration and policy formation are given different priorities in both theory and reality, necessitating a bridge. Additionally, only a few studies simultaneously focused on one of the three Panchayati Raj System tiers. The following Research Questions were the main focus of the current study, which sought to close any gaps.

Research Questions

RQ.1 Has the PRIs made enough action to expand its own source of income?

RQ.2 Is the public being consulted on decisions and issues involving revenue raising?

RQ.3 Do administrative and management restrictions affect the PRIs’ ability to collect money?

Method

The study uses a descriptive and empirical research design. Using the purposive sampling technique, six PRIs were chosen from the Bongaigaon and Cachar districts of Assam, respectively, to represent the Brahmaputra and Barak valleys of Assam. The sample units were 2 (two) Zilla Parishads, Bongaigaon and Cachar 2 (two) Anchalik Panchayats, Tapattary and Narsingpur, and 2 (two) Gaon Panchayats, Bongaigaon and Dholai. OSR data was collected over five years, between 2017–2018 and 2021– 2022. Data for the study was gathered through interviews with PRI officials and secondary sources. The researchers manually visited each sample unit because the secondary reports were not accessible through any online data sources or websites.

In Bongaigaon ZP, Tapattary AP comprises 11 GPs with approx 1.24 lakh population. In Cachar ZP, Narsingpur AP consists of 16 GPs with approximately 1.30 lakh population. Bongaigaon GP has an estimated 8601 people, and Dholai of Cachar district has a 7218 population. While taking the sample PRIs for our study, we considered the population criteria of (6000-10000) as given in the Assam Panchayat Act 1994 for establishing a Gaon Panchayat.

Data Analysis and interpretation

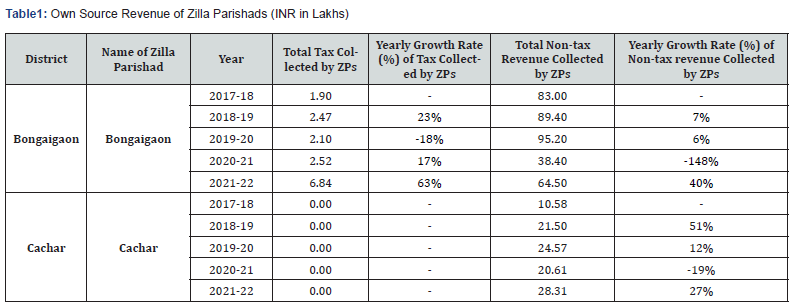

We tabulated the secondary information obtained from the offices of the sample PRIs in the districts of Bongaigaon and Cachar. Appendix-I contains references to Tables 1-3.

OSR position in Bongaigaon and Cachar ZPs:

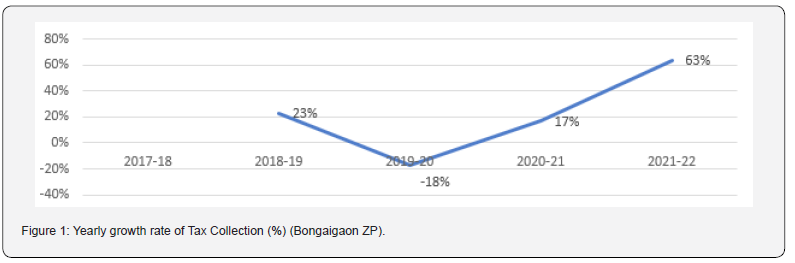

From Figure 1, we can deduce that the Bongaigaon ZP collected 23 percent more taxes in 2018-19 than in 2017-18. In 2019-2020, however, tax revenue declined by 18% compared to 2018-2019. We can attribute the cause to the lockdown situation during Covid-19 when the government restricted people’s mobility in response to a pandemic outbreak. 2020-21 will witness a 17 percent increase in tax receipts compared to the previous fiscal year, followed by a staggering 63 percent increase in 2021-22.

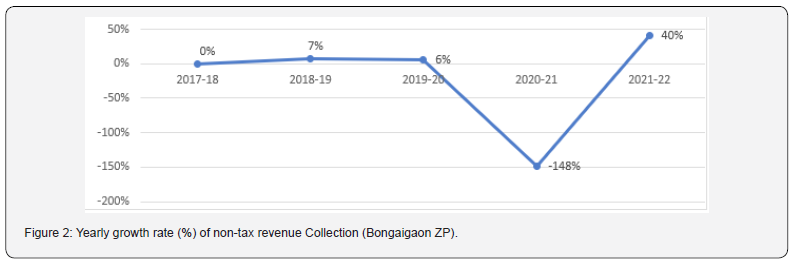

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the Bongaigaon ZP’s Non-tax revenue collection. The total tax revenue collected by ZPs in Bongaigaon was much lower than the non-tax revenues during the five years (2017-18 to 2021-22).

Comparing 2018-19 to 2017-18, we observe a 7 percent marginal increase in the collection of non-tax revenues. In 2019- 2020, however, the collection rate decreased to 6%. During the Covid-19 period, non-tax revenue collection continued to fall and showed negative growth, as anticipated. During 2021-22, however, the growth rate of non-tax revenues increased to 40%. License Fees, Permit fees, Registration Fees, and Penalties & Fines accounted for most non-tax revenue.

Secondary data on Cachar ZP tax receipts was unavailable during the study period. Only data on non-tax revenues were supplied. Due to a lack of personnel, field-level functionaries such as tax collectors were put as Junior Assistants in the Cachar Zilla Parishad, and no concentrated attempts were made for tax collection, resulting in no tax income being collected during the period (Refer to Table 1 in the Appendix-I).

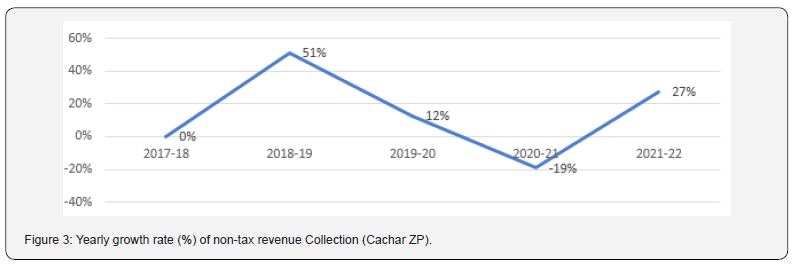

From Figure 3, we see that the non-tax revenue collection for 2017-18 was 10.58 lakh rupees, which increased to 21.50 lakh rupees in 2018-19, representing revenue growth of 51 percent. In 2019-20, however, it increased by only Rs 24.57 lakh (12 percent) compared to the previous fiscal year. During the Covid-19 era, 2020-21, Cachar ZP’s revenue growth decreased by 19 percent, amounting to Rs 20.61 lakh. But, the subsequent 2021-22 had a positive and enhanced non-tax revenue growth of Rs 28.31 lakh with a maximum increase of 27 percent compared to the previous year (Refer to Table 1 in the Appendix).

Despite the restrictions posed by the Covid epidemic, the collection of non-tax revenues has been outstanding.

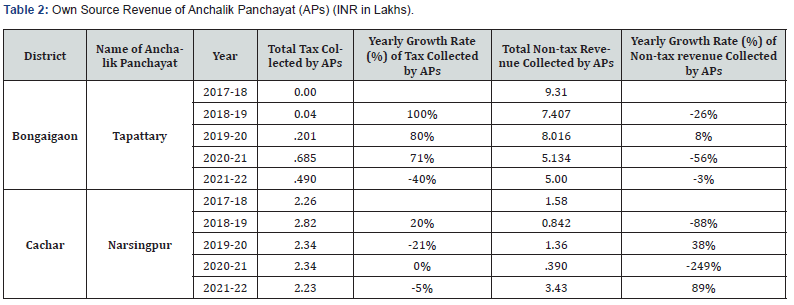

OSR position of Tapattary AP of Bongaigaon and Narsingpur AP of Cachar:

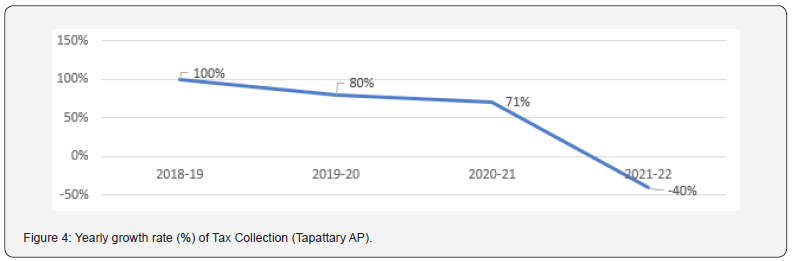

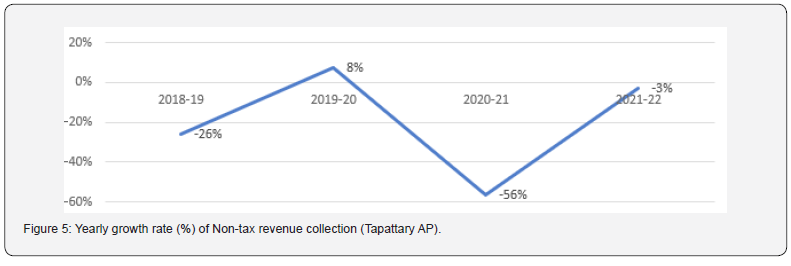

Figure 4 In Bongaigaon District’s TapattaryAnchalik Panchayat in 2017-18, non-deposit of any payment into the bank account was one of the primary causes of the lack of tax income collection. For day-to-day business, all transactions were conducted in cash. During the 2018-2019 fiscal year, new tax collecting and accounting personnel were hired. A sincere effort was demonstrated in tax collection and adequate upkeep, resulting in a 100% growth rate during that period. The principal sources of non-tax revenue include the settlement of Hat/Ghat, a 40% share of Hat/Ghat from Bongaigaon Zilla Parishad, and earnings from selling tender forms Figure 5.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the Anchalik Panchayat’s inability to collect lease rentals from the lessee of the Milan Bazar market were primarily responsible for the highly negative growth rate of non-tax income collection, which was (-) 56 percent for 2020-21.

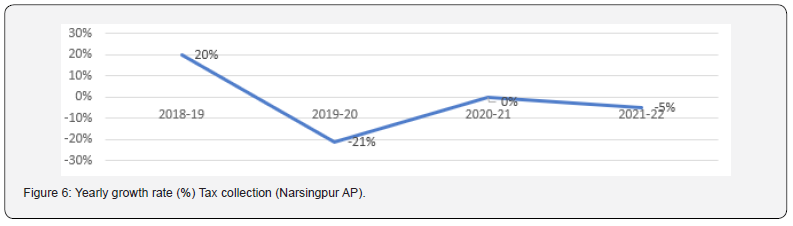

From Figure 6, we observe that the tax collection of Narsingpur GP plummeted from a positive growth of 20 percent in 2018-20 to a negative 21 percent during 2019-20. In 2020-21.

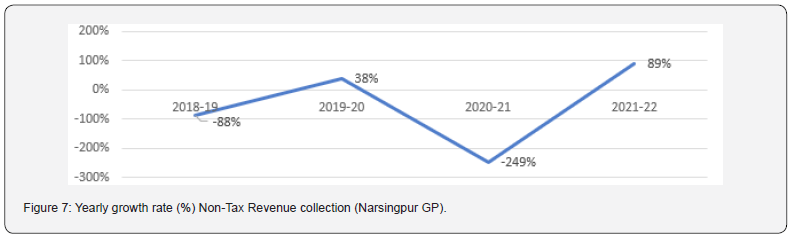

From Figure 7, we observe that the non-tax revenue collection of Narsingpur AP in 2018-19 registered a negative (-88) percent revenue growth compared to the previous year, 2017-18. In 2019-20 however, the revenue collection recovered a 38 percent growth but plummeted to a negative (-249) percent in the following year of 2020-21. This is obviously because of the Covid pandemic situation and its associated lockdown issues. The non-tax collection of Narsingpur GP registered a positive growth of 89 percent in 2021-22.

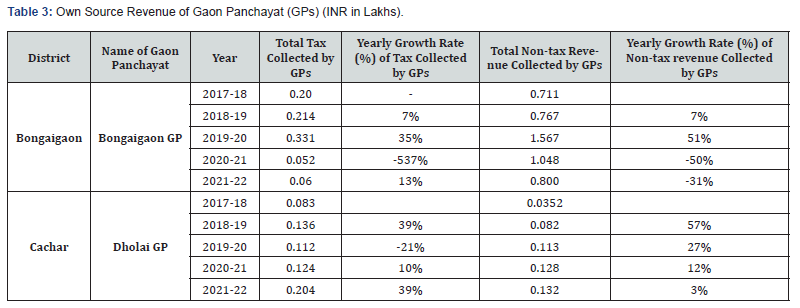

OSR position of Bongaigaon GP, Bongaigaonand Dholai GP, Cachar:

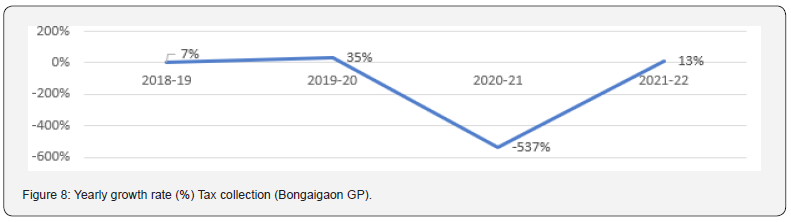

During the fiscal year 2020-21, tax revenue collection declined by (-537%) compared to the previous fiscal year, which had a 35% growth. The negative growth can be primarily attributed to the Covid pandemic effect. After careful observations of the OSR status of the PRIs, we find that the primary source of tax revenue collection in the PRIs of Bongaigaon was from House tax. Since the GP is near the State highway, there is more tax revenue opportunity. However, despite having this advantage, the GP needed to show a satisfactory growth rate.

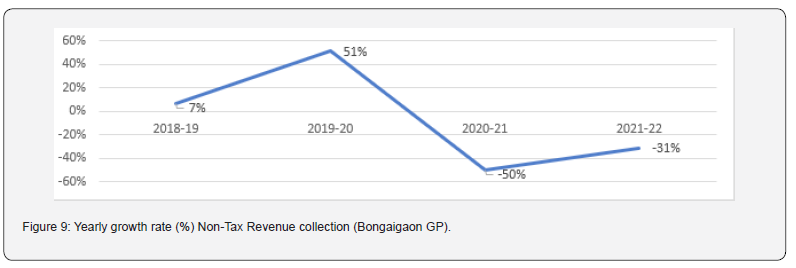

As indicated in Table 3, Figure 8, and Figure 9, throughout the five years from 2017-18 to 2021-22, the Bongaigaon GP collected more non-tax revenues than tax revenues. Nevertheless, the annual growth rate of revenue collection (including tax and non-tax revenue) was poor, with negative growth rates of (-50%) and (-31%), respectively, for the two years 2020-21 and 2021-22 (Figure 9).

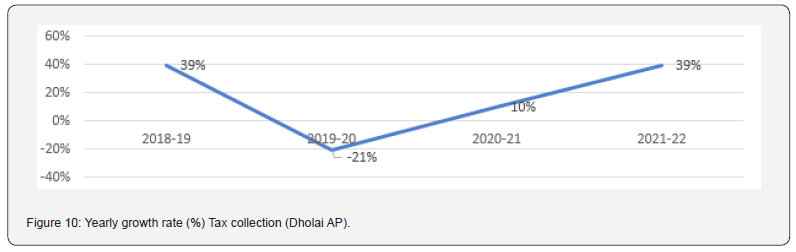

Figure 10 In the case of Dholai GP in Cachar, the collection of tax revenue climbed down gradually from 39 percent in 2018- 19 to (-21) percent in 2019-20. However, the group of non-tax revenue showed a rise during the Covid pandemic from a negative growth of (-21) percent to a positive increase of 10 percent in the year 2020-21. This further grew to 39 percent with a total revenue collection of 0.132 lakh rupees in 2021-22 from 0.128 lakh rupees in the preceding year of 2020-21, which showed a growth in revenue collection of only 10 percent. In Dholai GP, the primary source of tax revenue was the building/house tax, and license fees were collected for giving trade licenses for starting a new business (known as Ita Bhatta).

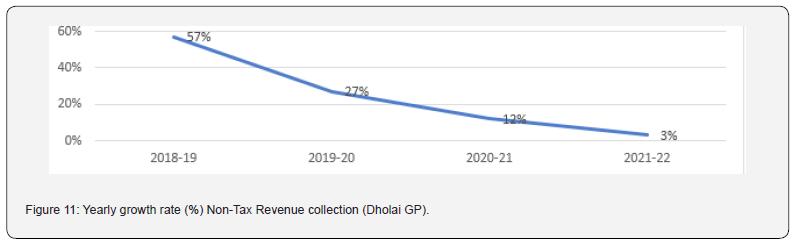

Figure 11 shows a 57 percent increase in non-tax revenue collection in Dholai GP of Cachar for the 2018-19 fiscal year. Non-tax revenue collection had a gradual fall to 27 percent in 2019- 2020, 12 percent in 2020-21, and 3 percent in 2021-22.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

After conducting the study and consulting with government officials, we discovered that the government and PRIs continue to make minimal efforts to establish revenue streams. The PRIs, particularly the GPs, are primarily dependent on Central and State funds for their developmental activities. We have yet to witness any new initiatives on their behalf to create internal revenue— this response to our investigation’s first research question. The second question asks whether or not the public is consulted on tax collection decisions and concerns. We noticed an absence of tax and fee consciousness among the populace. During Gaon Sabhas (village assemblies), when the problem of generating revenue from one’s sources can be emphasized for better public awareness, this deficiency may be remedied. To answer the third research question of whether administrative and management constraints affect the ability of PRIs to collect funds, it is essential to consider the recent cabinet decision made by the Assam government. The government should review its decision to remove the non-requirement of trade licenses and the suspension of the imposition of any tax or fee by Gaon Panchayat, Anchalik Panchayat, and Zilla Parishad for the establishment of business operations, shops, etc. OSR is the lifeblood of PRIs. Hence it must be given appropriate importance for the local bodies to grow sustainably and become less reliant on government subsidies and grants.

Declaration of Conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgement

One of the authors of this article, Anulekha Bhagawati, is a recipient of Indian Council of Social Science Research Doctoral Fellowship. Her article is largely an outcome of her doctoral work sponsored by ICSSR. However, the responsibility for the facts stated, opinions expressed and the conclusions drawn is entirely that of the author. The authors are also grateful to all the CEOs of the Zilla Parishads as well as the officials for their supportive gesture in the survey process.

References

- Munyua CM, Muchina S, Ombaka B (2021) County Governments Own-Source Revenue and the Performance of Women-Owned Micro Enterprises in Kenya. December.

- Rao MG, Rao UAV (2008) Expanding the resource base of panchayats: Augmenting own revenues. Economic and Political Weekly 43(4): 54-61.

- Luiz D, Barenstein M (2001) Fiscal decentralization and governance: A cross-country analysis. (IMF Working Paper No. 01/71).).

- Jha R, Nagarajan HK, Tagat A (2019) Restricted and unrestricted fiscal grants and tax effort of panchayats in India. Economic and Political Weekly 54(32): 68-75.

- Chakraborty S (2016) Own Resource Mobilization of Panchayats: An analysis with special reference to Howrah District of West Bengal (Doctoral dissertation, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore, West Bengal, India).

- Zakir AM M, Islam Nurul (2017) The Assam Panchayat Laws, Assam Law House, North Sarania, Guwahati, First edition.

- Khadondi S (2016) Determinants of Own Source Revenue Mobilisation by Counties in Kenya. International Journal of Science and Research 5(11): 155–164.

- Palharya S (2003) Decentralised Governance Hampered by Financial Constraint. Economic and Political Weekly pp. 1024-1028.

- Coker MA, Adams JA (2012) Challenges of managing local government finance in Nigeria. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 2(3): 1-12.

- Ratra P, Dahiya J (2022) Decentralization and Challenges Related to Panchayati Raj Institutions in India. Asian Journal of Sociological Research 6(4): 26-34.

- Chepkoech N, Gichana JO, Agong D (2022) Effect Of E-Payment Systems on Sustainable Revenue Collection in Nairobi City County Government. International Academic Journal of Economics and Finance 3(7): 238-253.

- Ma G, Mao J (2018) Fiscal Decentralisation and Local Economic Growth: Evidence from a Fiscal Reform in China. Fiscal Studies 39(1): 159-187.

- Mbau EP, Iraya C, Mwangi M, Njihia J (2019) An Assessment of the Effect of Fiscal Decentralisation on Performance of County Governments in Kenya. European Scientific Journal ESJ 15(25).