The Past, Present, and Future of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises: A Historical Materialist Interpretation

Ruiyang Hu1* and Mo Xu2

1Department of Political Science, School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Fudan University, Shanghai, The People’s Republic of China, China

2Common Prosperity Laboratory, Innovation Center of Yangzi River Delta, Zhejiang University, Jiaxing, China

Submission: April 23, 2024; Published: May 02, 2024

*Corresponding author: Ruiyang Hu, Department of Political Science, School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Fudan University, Shanghai, The People’s Republic of China, China

How to cite this article: Ruiyang Hu* and Mo Xu. The Past, Present, and Future of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises: A Historical Materialist Interpretation. Acad J Politics and Public Admin. 2024; 1(3): 555565. DOI:10.19080/ACJPP.2024.01.555565.

Abstract

Literature on the reforms of China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) mainly focuses on mere descriptions of the history of reforms. Most of the literature argues that SOE reforms were the results of internal conflicts among leaders. Most of them have ignored the logic behind the reforms of Chinese SOEs. This article will review critical policies of Chinese SOEs’ reforms and use historical materialism—the interactions between the productive forces and relations of production—to explore the reform process behind Chinese SOEs. This article will conclude that leaders will do not drive the reform process of Chinese SOEs; instead, it has an unstoppable logic primarily driven by the development of productive forces. In the end, the article proposes three possible outcomes for the Chinese economy and argues that subject initiatives are important in deciding the direction of the development of productive forces.

Keywords: Chinese political economy; Marxism; Historical Materialism; Socialism; State; State-owned enterprises reform

Introduction

China has been the second-largest economy for more than ten years, and its economy has experienced continuous growth for more than 40 years. If this trend continues, the Chinese economy will surpass the United States in this decade. The Chinese economy is not simply a fast-growing economic entity but also a socialist one. Its competition with the US is not just a competition in fields of economic growth but also the competition between two different social systems. Therefore, it is essential that scholars interpret the evolution of the Chinese economy not only in purely economic terms but also in terms of political economy. One of the most essential components of the Chinese economy is the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) system, which has been regarded as the core actor of the socialist economy.

From 1949 to 1978, private capital and private ownership were almost extinct in China. The SOEs system, also known as the “whole people” owned industrial enterprises, was the sole type of SOEs. Since the reform and opening-up policy was first introduced in 1978, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has begun to reform its economy and seek constant economic growth. The introduction of the reforms in urban SOEs in 1984 officially marked the legal appearance of private capital in urban China. The adjustment and acknowledgment of private ownership in the Constitutional Amendment of 1988 and the introduction of market reform in 1992 marked the speeding up of the reform of the SOEs The State Council [1]; The Central Committee of the CPC [2]. Until today, despite the total number of SOEs being largely smaller compared to the 1980s, SOEs’ assets still occupy nearly half of the company assets in China Chen [3]. There has been much literature focused on the history of SOE reforms. Most of them shared awe-inspiring accounts of the reforms of SOEs. However, these works focused mainly on the introduction and description of the history. Sometimes, the literature even arbitrarily portrayed the reform of the SOEs as a path to capitalism without asking why all of this had happened. The pre-existed literature usually overlooked the Marxist logic behind the reforms of the SOEs Lin [4]; Frazier [5]; Chen [6]. Was the reform of Chinese SOEs a path to capitalism initiated by the leadership? Was there any logic behind these reform policies, and did leaders’ decisions matter the most? Addressing these puzzles, this author will argue that the reforms of the SOEs are the results of constant struggles between the production forces and relations of production, and through the lenses of historical materialism, the reforms of the SOEs have their historical necessities. By conducting such research, the authors wish to present the readers with a basic knowledge of why these reforms of SOEs have happened and how these reforms may influence the Chinese economy in the future.

Literature Review and Mapping

Some scholars have interpreted the reforms of Chinese SOEs merely as the results of bunches of policies proposed by Chinese leaders. Leading scholars such as Zhang Dicheng, who has written four volumes on the reforms of SOEs, concluded that the reforms of SOEs were wise decisions of Deng Xiaoping. Zhang’s work has provided scholars with countless historical details yet without the reasons on why reforms of SOEs have happened Zhang [7]. Some scholars have noticed that one of the reasons behind the SOEs’ reforms was the need to improve the productivity of SOEs. Nevertheless, when explaining why China was keen on improving its productivity or the subsequent consequences after the inmprovement of productivity, these scholars, some of which did not even address such puzzles, tend to emphasize on Deng’s hope of allowing Chinese people to have a good life that caused these reforms instead of analyzing them from a Marxist perspective, 2016; Wang [8]; Zhang [9].

Some scholars namely Denial Dell and Ross Garnaut viewed the SOEs reforms as the necessary stage before realizing socialism in China, and these scholars, from a non-Marxist perspective, viewed nowadays China as a capitalist nation. This point of view believed that in the pre-1978 era (that is before the SOEs reforms and China’s opening up), the developmental goal of the Chinese economy was to surpass the stage of capitalism. Therefore, the post-1978 period was the time to attend a “make-up” class for China, and the missing class is called the class of capitalism. However, this kind of argument also ignored why China needed to take the “make-up” class. Furthermore, these works also have the problem of using academic work as a political tool. They usually view the post-reform period of the CPC’s rule as illegitimate and somewhat authoritarian Bell [10]; Garnaut [11]; Oi [12]; Yu [13]; Yu [14]; Zhang [15]. Other scholars, such as Isabella Weber, also wrote about the Chinese reforms. Weber saw the reforms as a path to capitalism and viewed the reforms as consequences of struggles among top leaders. Weber argued that the top leaders’ conflicts resulted in many critical decisions, and eventually the leaders who had knowledge of western political economy prevailed and occupied key positions in the economic reform Weber [16]. In these scholars’ works, the free market economy is regarded as the best economic system for China.

There are also many scholars such as David Harvey and Lin Chun who have talked about the reforms of SOEs from the classical Marxism perspectives. Nevertheless, most of them saw Chinese reforms as the path to capitalism. Lin Chun’s books emphasized the argument that Chinese reforms went from an investmentdriven planned economy to a market-driven economy. As the official narratives largely ignored the exploitation of rural farmers and urban workers, the nature of reform, however, was no longer socialist Lin [4]; Lin [16]. Scholars such as David Harvey and Huang Yasheng openly concluded the nature of Chinese reform as the practice of neo-liberalism. They believed that the policies of mass laying off of workers from the SOEs, mass privatization campaigns, and massive allowance of the influx of foreign capitals were all the core ideas of neo-liberalism Harvey [18]; Huang 2008; Li [20]; Ma [21]; Smith [22]. However, these scholars also had the shortcomings of ignoring the basic logic behind the reform policies. David Harvey did use some Marxist interpretations, but for exploring the reasons behind the key turning points of reforms, such as the reform and opening up in 1978, the transition from plan to market in 1992, and massive privatization in 1997, David fell short on explaining these (2005).

Nevertheless, despite all of the literature having fallen short of explaining the reasons behind the reforms of SOEs, most of them have supplied many historical details, which will be referred in the historical descriptions in this article. This article will offer readers the key reasons why reforms of SOEs have happened, and the authors seek to explain the logic using the lenses of historical materialism. As the article’s title says, some parts of the article will be spent describing the critical historical events of SOE reforms’ past, present, and future. The authors believe that this article will fill the gap in the literature in two ways. Firstly, it will be an article based on using historical materialistic lens to view the reforms of SOEs as almost no literature has viewed the reforms in this way. Second, it will be an article that focuses explicitly on China which will be helpful for scholars who are specialized in political science and area studies. At the same time, the authors also acknowledge, that due to the established word limitations, this article will focus on major reforms of SOEs, which means only macro policies will be discussed, and it will unavoidably fall short of investigating detailed policies in the reforms of SOEs.

The Classical Marxist Debate

Interactions between productive forces and relations of production are one of the key ideas in Marxist theory. As Marx [23], [24] argues in The German Ideology and his later work Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, in the everyday actions of individuals, they need to survive; they have needs, and hence they need to produce. The necessity of production requires humans to produce goods collectively, which later turns into factories and machine productions, and it requires human organisations and division of labor. Following this logic constitutes the idea of the mode of production. Under the mode of production, when humans use machines to produce collectively in the same factory, it is by nature that workers own what they have produced because they inject labor into it. However, under the capitalist application of machine production, machines are the means of production owned by capitalists, and workers only get wages as the sole type of reward. The wage, however, only constitutes part of the value of their outputs; the rest of the value of the outputs becomes surplus value Marx [25]. As a result, the more workers have produced, the cheaper the price of goods has become, and hence the lower wages and more suffering for workers; workers are alienated from their products Marx [26]. These are the core features of capitalist relations of production. Aside from alienation, capitalist production also produces countless quantities of products. The increase in productivity (in many ways, such as by division of labor, technological advancement, more investment, etc.), and hence in productive forces, will not only lead to more surplus values but also to the uncontainable power of the advanced productive forces. Marx [27] argues in the Manifesto of the Communist Party:

Hitherto, every form of society has been based, as we have already seen, on the antagonism of oppressing and oppressed classes. But in order to oppress a class, certain conditions must be assured to it under which it can, at least, continue its slavish existence...The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.

It is to say, when a type of relation of production can no longer contain the development of the productive force, the productive forces will override the relation of production and establish a new one that is suitable for the productive force. It seems that the development of productive forces always drives the direction of the relations of production; however, the logic is more complex. In the Preface of a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (the Preface), Marx [28] explicitly points out that

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces, these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution.

It means that although productive force dominates the relationship between productive force and the relation of production, the relation of production dominates the framework, which means that the relation of production somewhat contains the direction development of productive force. In Marx’s work The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte and The Civil War in France [29]; [30], he explicitly argues the need to take subjective actions to change the relations of production when the capitalist productive force had matured. If the proletariat takes no actions to break the bourgeois state machine, the ideal socialist republic would never come, and the superstructure (the relations of production) would remain capitalist. All of the above is to prove that Marx had never valued the productive forces that always drive the direction of the relations of production. Subjective initiatives from the proletariat are essential when necessary conditions are matured. This point will reappear later in the text.

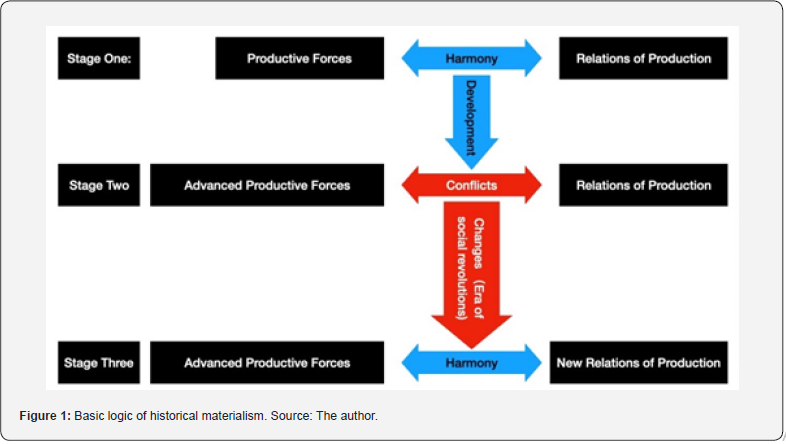

Historical materialism is generated from the interactions between the relations of production and productive force, and it means the unstoppable trend of development of history. As Marx [24] mentions in The German Ideology, only when the capitalist mode of production has occupied the leading position in global society and everyday communication has been established among humans will history become “global history,” where every part of the globe is dragged into the expansion of the capitalist mode of production. Only at this point can an advanced productive force overthrow the old relationship of production entirely on a global scale, and this is the essence of historical materialism, and the final stage of the development of human society will be communism. It can also be found in Marx’s analysis in Capital. From handicraft production to machine production, Marx [23] argued that the implementation of machines first did not challenge the old relation of production under handicraft production; however, when machine production showed its advanced productive force, more and more places began to adopt machine production, and hence, the relation of production under handicraft production collapsed. In classical Marxist theory, historical materialism means the unstoppable development of history. When the old historical period develops and matures, the conditions for the next historical period will emerge. When the old period reaches its peak, the new one will replace the old; hence, history develops. If the old ruling class tries to maintain the old relations of production, the era of social revolution, the term used in the Preface, would begin. Such a way of interpreting historical development will be used in this article see Figure 1 Marx [28], and it is the methodology of this article.

Past: Pre-Reform Period

Major Reform Policies

The full establishment of SOEs system, also known as the Danwei System, was initially established in 1956 after the “Three Transformations”, a full-scale nationalisation campaign. Before 1956, the official tone was to allow the existence of private capital, and national planning existed only in key industries. The Soviets had offered 156 key industrial plans, and state plans were mostly focused on finishing those plans (Yi, 2019). The nature of the economy was backward. Starting from 1953, the CPC decided to transfer all private capital into public ownership. Instead of using the Soviet model, which had nearly eliminated all capitalists in physical terms, the Chinese way of transformation used the way of buying out all private ownership using state funds. Former capitalists could also get a small share of annual profit (si ma fen fei) Shi [31]. After 1956, public and collective ownership dominated the state economic system; in-laws and state policies, the CPC claimed the illegal practices of private ownership. Thus, China managed to maintain its public ownership despite its productive force being backward compared to not only the capitalist states but also the Soviet Union Lin [4]. Most of the SOEs in cities were officially called “Whole-people owned industrial enterprises” where the company needed to take care of every aspect of its activities. Workers enjoyed a variety of rights within factories. During the Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution, workers even enjoyed the right to overthrow the factory management bureau when they felt the bureau was “counter-revolutionary” Lin [4]. Workers’ rights were put before profits, and any practice of putting profits before workers’ rights was denounced. There were also severe regulations on Danwei; they needed to fulfill state quotas and establish full protection of workers’ rights and welfare. The Danwei system generated continuous growth from the 1950s to the 70s, as China has finished its industrialisation process with 20 years Mei [32].

During this period, the SOEs/Danwei also cared about workers’ welfare all the time. Under regulations, a typical Chinese Danwei included factories and low-rent apartments, entertainment facilities, and sometimes even farms for workers to learn agricultural skills to minimise the gap between urban and rural areas. Danwei also had many affiliated factories, which were usually responsible for the production of products for enjoyment, such as soda, ice cream, candies, etc Lin [4]; Schrumann [5]. In Danwei, workers were regarded as “masters. Much of the profit that Danwei generated was spent on these services. A case study of the Zhengzhou Textile Factory (the Factory) will show what a typical Chinese Danwei looks like: workers in the Factory enjoy various kinds of welfare services. This Factory was constructed in 1958 as an Industrial Enterprise. It employs over 10,000 workers and is a large Enterprise in China. Workers’ representative congresses, cadres, and managers control the distribution of welfare services for workers. Public meeting halls, kindergartens, clinics, and primary schools have been established. A factory-sponsored worker university was constructed to offer multidisciplinary courses to workers Schrumann [5]. Hence, the SOEs during this period were a body that centralised all the materials in its hands in order to organise workers producing goods for state plans. It was much more efficient in this period when compared to unorganised, backward, privately owned industries.

Why Reforms Have Happened?

From the perspective of historical materialism, prior to the full-scale nationalisation in 1956, the productive force of private ownership was backward and unsustainable, and a new relation of production was needed. The urban industries were backward in the 1950s. The relation of production, however, was also backward, and many old regulations from the Nationalist era remained. With the gradual accomplishment of the Soviet plans, these advanced industries, which represented the advanced productive force, required massive growth of urban areas. With the need for urban constructions and to fulfill urban newcomers’ basic needs, a new relation of production was needed to cooperate with the rapid development of productive forces. Hence, the new relationship, by claiming the absolute dominance of public ownership, centralises critical resources into the state’s hands to catch up with the need for productive forces.

For the Danwei system, when the time came to the late 1970s, such a system was not sustainable enough. The establishment of new relations of production after 1956 aimed at catching up with advanced productive forces; it did generate continuous economic growth; until the 1970s, the annual growth of economic output was nearly 10%, which was remarkable. However, the Danwei system only covered 20% of the Chinese population at its peak, and most of the people could not enjoy the services of Danwei. The productive force in China was far from realizing the goal of Danwei. Most of the rural population, which composed more than 70% of the people, either could not come to cities for work or live in absolute poverty. For those ones who registered in Danweis, their living standard was also relatively low compared to the Soviets and East European countries Walder [34]. The Danwei system cares about almost every aspect of a worker’s life. It aimed to establish a very advanced production relation where workers were the masters and democratically set production quotas and distributed welfare services. It requires a very advanced productive force whose output could fulfill everyone’s needs, and the productive forces, in reality, however, were far from fulfilling everyone’s needs. Therefore, prior to the reform, the SOEs/ Danwei system was the advanced relation of production meeting the backward productive force, and the decisive actor in this relationship was the productive force. The backward productive force would require a suitable relation of production, which would allow freedom for capital to invest in expanding reproduction rather than focusing too much on workers’ consumption and enjoyment. The SOE reform would take place no matter who was in power.

Past: The Reform and Opening Up

Major Reform Policies

The reform period of 1978–1998 have witnessed a remarkable transformation of the SOE system, not only in their management style but also in their attitude towards them. Already in 1978, Deng Xiaoping had his idea on economic management, which was that the CPC should regard technology and development (the productive force) instead of revolution (the relation of production) as the priority. Deng [35] has said that “science and technology are the primary productive forces.” In the same year, the CPC launched a very long debate on whether to acknowledge the legacies of the Cultural Revolution and one of the most important fields of the debate was whether to reform the SOEs to develop productive forces or continue to hold revolutionary legacies (whateverisms). In the end, as Deng [36], Deng [37] quoted in his “Black Cat and White Cat” theory in the 1960s, whoever catches the mouse decides which one is a good cat, and the core arguments of the article “Practice Is the Sole Criterion for Judging Truth” prevail. The “practice” means the need to develop productive force. It marked the moment when the debate between socialism and capitalism came to a halt, the legacies of the Cultural Revolution were negated, and the CPC decided to put the development of productive forces before the relation of production Central Committee of the CPC [38]. In 1984, the CPC began to allow the existence of the “double-price” system (jia ge shuang gui zhi); SOEs were allowed to manipulate the goods produced out of the state quotas instead of handing in every piece of product to the state. Slowly, a market outside the state plans was established, and SOEs could bargain with other SOEs (later other private owners) on the price of goods. The witnessed increase in economic production was dramatic; SOEs were excited about producing in order to make more profits for themselves Central Committee of the CPC [39].

The change of attitude towards SOEs in the reform period was prominent, especially in expanding management rights, as well as other regulations on the economy. In 1985, the CPC established the “responsibility system (baogan)” in cities and ordered factory managers to take responsibility. The aim was to order factories to maximise production and minimise expenditure on workers’ welfare in order to expand production quickly. The state signed production contracts with managers; afterward, factory managers could use any possible way to fulfill production quotas. Since then, the SOEs have been allowed to sack and hire part-time workers who do not need housing or other welfare services Lin [4]; Lin [17]. In 1992, in Deng’s South Tour, he (1993) argued that a planned economy is not equivalent to socialism, because there is planning under capitalism too; a market economy is not capitalism, because there are markets under socialism too. Planning and market forces are both means of controlling economic activity. Therefore, at the end of 1992, the full introduction of the “socialist market economy” canceled state quotas, further emphasizing the importance of developing the productive forces, and the state no longer guaranteed protections for SOEs Central Committee of the CPC [40].

Since the late 1980s and early 1990s, the introduction of the Law of Whole-People Owned Industrial Enterprises of the PRC, the Company Law, and the “grabbing the big and releasing the small” policy in 1997 have marked the reorganisations of SOEs. Under the Company Law, managers did not need to be responsible for full workers’ rights; they only needed to purchase necessary social insurance for workers on the market, and for most of their time, they only needed to be responsible for the profits and capital of their companies (The Eighth Congress of the National People’s Congress of the PRC [41]. Some SOEs were re-registered under the law and changed from “Whole-people ownership” to “Company Limited” ownership The State Council of the PRC [42]. When the Company Law met the policy of “grabbing the big and releasing the small,” the reform process quickly became one of the most extensive privatisation processes globally. Former managers became capitalists, and officials enriched themselves by selling out enterprises. At the same time, tens of millions of workers lost their jobs and received nothing but a tiny amount of reparations from their enterprises Lin [4]. In 2003, the CPC established the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) to supervise the remaining large-scale SOEs and stop the privatisation trend. The SASAC acts as a monitor or collector of the profits of SOEs’ profits, and most of the SOEs officially became “national-owned (which is also known as Co.Ltd.)” where the only responsibility for managers is to handle production and expand reproduction of the company assets, and the workers’ rights were somewhat subordinated (SASAC [43]; Central Committee of the CPC [44]; Zhang [45].

However, during the reforms, there were also lots of problems. Firstly, the “double-price” system did encourage SOEs to produce more, but as the factory management bureau got rights through baogan, they began to use products for state quotas and sell them on the market (guandao) (Lin [4]; Gong, 2014). Also, they began to bargain with the state for the lifting of regulations as well as cut off state quotas on SOEs for them to produce more outside state quotas for more profits. Factory managers tried everything to cut off the quotas in their baogan contracts. In 1988, the inflation rate was out of control because the state could not control enough products to stabilise the market; most of the transactions were finished under market transactions Zhang [46]. From 1988 to 1992, the Chinese economy was forced to enter a period of transition as many old regulations were waiting for changes. The period was called “break through the barrier of prices” in order to adopt market prices and market relationships fully (Zhang [47]; Weber [16]. Third, after the adoption of market reform in 1992, under the Company Law and the SASAC, it was hard to monitor the assets of SOEs. There were cases where some SOEs sold out some assets in order to maintain the increase in profits Lin [17]; Lin [49].

Why Reforms Have Happened?

Many reform policies were quite counter-intuitive, especially those that targeted cutting off workers’ welfare. However, they were the results of the continuous interactions between productive force and the relation of production, and instead of regarding reforms as a leader’s will, the entire reform was driven by the triumph of productive force and how it has interacted with the relation of production. Before the reforms, most of the Chinese people were in poverty; the need to escape from poverty required SOEs to produce more profits and expand their production, which generated more job positions and allowed more workers to come to cities. No matter how the debate ended in 1978, the reforms would take place because too many people were left out of the state plans during the Danwei era, and continuous poverty would generate social conflicts. The reforms in the early 1980s were not intended to change the SOE system entirely; instead, they were designed to increase productivity in order to generate more profits for investment in expanding reproduction. With the observed increase in economic production (State Statistical Bureau [49- 51]; The World Bank [52], the more people came to cities, and SOEs had more money in their hands to reinvest. Therefore, as the productive force of the SOEs develops, it will naturally demand a change of policies that were set up prior to the reforms in order to get more freedom to invest capital in profitable areas. The change of regulations on SOEs would unavoidably need changes.

With the demand to catch up with the development of productive forces, the relations of production needed to change. The first change was the regulation to hire and sack part-time workers. Also, introducing the “double-price” scheme officially relaxed the state plans, and the state began cultivating a market beside the plan. Together with the expansion of the power of the management bureau under the baogan policy, SOEs had more freedom to produce and sell more outside the state plans. Because the market price was more profitable, with the increase in productivity, SOEs naturally wanted more freedom to sell their goods at the higher market price, and when more and more SOEs produced and exchanged on markets while trying to minimise produce for the state, the entire price system and hence the economic system needed a reshuffle. It was impossible to impose rigid regulations on SOEs again; the only possible way was to lift the remaining price control and allow market rule to dominate the exchange of goods. The change of price scheme marked the starting point of changing the plan to market. With the transition from planned price to market price finished, the introduction of the market economy and other regulations in the 1990s were the consequence without extra effort.

When the new market economy system and the entire relationship of production were taking place, it was impossible for all the SOEs established during the planned economy era to remain profitable when state protections left. To further generate more profit, the “grabbing the big and releasing the small” policy in the late 1990s changed non-profitable SOEs into private ownership and changed many SOEs to a solely profit-oriented nature because making the enterprises survive was the top priority. By keeping profitable big SOEs in the state’s hands with a “company limited” nature, the CPC could obtain economic control under the market economy and allow most SOEs to focus solely on profit-making. Together with other non-SOEs, the potential of productive force was unleashed. The establishment of the SASAC in 2003 was a sign of adjustment under the established relation of production. The SOEs’ decisions mainly were still controlled and influenced by the party and government bureaus in China before 2003. One of the most essential needs is to offer SOEs more authority to make key decisions under market rules to unleash the potential productive force of SOEs. The SASAC, by acting only as a monitor of SOEs’ assets, allowed SOEs to make decisions under market rules, which allowed SOEs to increase their productivity and enhanced the position of the relation of production established after 1992.

Present: Xi Jinping’s Reforms

Major Reform Policies

Since Xi came to power in 2013, some adjustments have been made to the regulations of SOEs. From 2013 until today, the SOE system has undergone several noticeable adjustments. The first set of reform of the SOEs such as the three-year plan on reforming the SOEs (2017–2020) and state-owned enterprise reform deepening and upgrading actions (2023–2026) were initiated by the SASAC. These two policies aimed to transform all the remaining “whole-people” SOEs into “company limited,” and all of the welfare and affiliated services of the SOEs will be put under market competition. SOEs’ sole job is to make more profits under market rules. Private capital and SOEs were regarded as the same under market rules SASAC [53]; Zhang [54]. Another important feature is the full-scale return of the labor contract. Before the reforms, some of the biggest SOEs (central government-owned) did not fully adopt the labor contract system, and employees were employed lifelong. After signing a labor contract, the SOEs are now able to impose quotas on employees during the contract period, and they can sack those who cannot meet the quotas Guo [55]; Zhang, 2020). The third feature is the mixed ownership reform. Several SOEs, such as the State Grid, China State Railway Group, and China Petroleum Group, have all transferred and traded part of their shares on the stock market. By doing so, private capital can join in and influence the decisions of the SOEs. On SOEs’ boards of directors, representatives of private capital have been allowed to join. By now, the SOEs are no longer solely controlled by the party and the state but are also significantly influenced by private capital Lin [4]. In the future, according to official policies, the SOEs will continue to break the “monopoly” in areas such as gas, oil, electricity, railways, and so on. More and more signals show that the SOEs will continue to mix with private capital, not only on their shares in stock markets but also in any other possible areas.

The CPC also made several adjustments to the regulation of the market. The first is the State Administration of Financial Supervision and Administration, established in March 2023 to supervise all the financial situations of the SOEs, especially those state-owned banks, insurance companies, and stock companies. There are also regulations such as the policy of “preventing the disorderly expansion of capital” and “two principles (unswervingly consolidate and develop the public sector of the economy; unswervingly encourage, support, and guide the development of the non-public sector of the economy).” Developing SOEs are encouraged, but they cannot expand disorderly. Private capital is also prevented from uncontrolled expansion Central Committee of the CPC [56]. These regulations will be in effect in the future, and under a more regulated market, the SOEs will be regarded as the same as private corporations, and the party will act as a regulator where the official regulations no longer protects all SOEs in theory.

Why Reforms Have Happened?

The reform policies and regulations on SOEs result from the need to develop the national economy and, hence, the productive force. Under “whole-people” ownership, welfare and other kinds of affiliated services were under no regulations or supervision. When all SOEs were regarded equally under market relations, affiliate services were obstacles to profit-making. SOEs would naturally seek ways to transfer those services to others who are experts in them. Therefore, the need to change the remaining SOEs into “company limited” ownership has been created. By doing so, SOEs can legally get off all the affiliated services. Under “company limited” ownership, the supply of welfare and affiliated services is no longer the duty of the SOEs; they could either purchase these services or simply buy social insurance for their employees Liang [57]; Li [58]; Zhang [54]. Instead of treating maximisation of workers’ welfare and rights as one of the goals of SOEs during the pre-reform period, they are now treating workers’ wages, welfare, and all the spending on affiliated services as part of company expenses; their goal is to minimise them. Increasing the productivity of SOEs would further require more freedom in their capital investment, which requires a change in the party’s regulations on SOEs. When the new SOEs mix with private capital, the freedom of investment is realised. As an example, after relaxation on capital investment, the profit of SOEs continues to rise at a fast rate (around 10% annually) even if there are difficulties such as the pandemic SASAC [43]. However, the direction of development of productive forces of SOEs might go wrong or the influx of private capital might result in the loss of state-owned assets; therefore, the party has also introduced refroms and other policies to prevent them from happening.

During this period, we can identify many interactions between productive forces and relations of production. Under the regulations above, the reform policies and regulations are seemingly not preferable for SOEs because the CPC seems to, on the one hand, let go of all the protections for them while also setting some limits on its expansions. However, it is the unique characteristics of Xi’s period. On the one hand, the development of SOEs’ productivity has resulted in the change of relations of production (state policies) on the other; meanwhile, the party has always tried to influence the direction of development of productive forces. These regulations encourage SOEs to develop and expand in a socialist direction while also preventing the loss of control of SOEs (i.e. after they have expanded disorderly or after the influx of private capital). Although these reforms and regulations have taken place, the SOEs still hold the high ground in the national economy because they are expanding and continue to dominate in key areas of the national economy.

Future: Where to go?

Current Economic Difficulties

Today’s Chinese economy is facing structural difficulties. There are two significant difficulties. First the problem of involution (nei juan). Major Chinese cities are now holding a variety of resources, and there are limited job positions in cities and most of the enterprises (including some SOEs) has been focusing on profitable and high-salary sectors such as finance, real estate, insurance for too long time. The profits in these none substantial economic sectors has depleted while investment in substantial economic sectors is decreasing, and jobs in substantial economic sectors are usually less well paid and sometime in harsh conditions compares to a finance manager who always sits in air-conditioned environment. It is now very difficult to create more demands hence more job opportunities in these non-substantial economic sectors Zhang [59]. When limited well- paid jobs meeting with a growing urban populations who want to get these jobs, it will result in a growing unemployed populations, and competitions are severe (nei juan). However, this is not the whole story. Due to a growing urban populations in major cities, demands for basic municipal services will rise, which will result in the growth of the price of these services in cities. The most prominent conflict is between the un-affordable cost of real estate and meager wages or even unemployment for young people especially after 2008 National Bureau of Statistics [60]. The most important task is to divert some resources into substantial economy and to create more jobs not only in major cities but also in other non-major ones.

Second, a society-wide low income for Chinese workers which has generated the decline of population, and it is a sign of depression. China is now facing a population decline since the 1960s, and the fall is not because of natural causes Larmer and Zhang [61]; Tian [62]. As Marx [63] argues, one of the most critical measurements of a nation’s economic condition is whether the population can maintain expanded reproduction. If the population is shrinking, the entire economic system is in a state of depression because an expanding labor force is the key to expanding reproduction in capital. Shrinking populations mean the need for structural changes. The potential shrinking of the labor force in the short term future means the current wages, subsidies, and other kinds of rewards for workers are not enough for them to feed the next generation. When such a sustainable wage continues for a longer period, people would not be willing to consume commodities other than those can support their basic needs, and it would result in low-demand society; the entire economy would come to long-term depression Marx [64]. However, some might argue that the influence of a shrinking labor force would appear decades later, but actions such as increasing wages, redistribution of resources, and other kinds of incomes for workers must now be taken to avoid prospective consequences. Some might argue that less population means less potential for nei juan; however, as the Chinese population amount sets by, waiting for the natural population decline to solve nei juan is impossible in the forthcoming decades.

To conclude shortly before entering the analysis of the future Chinese SOEs, the future Chinese economy is facing some structural difficulties, and there are mainly two critical problems that are waiting to be solved. First, to solve the problem of nei juan, more investment in order to create more demands in substantial economic sectors. Second, more incomes for workers in order to avoid future population decline. SOEs, under such a difficult situation, will also be influenced. Dialectical speaking, difficulties also mean opportunities. The sign of difficulties meaning solutions are possible. As we analyzed previously because SOEs are still playing their dominant position in the development of productive forces, the possibilities of reforming relations of production by using SOEs are on stage, and the key is whether the party take active actions or not.

Three Possible Outcomes

An Overview of the CPC’s Actions

From the analysis in previous sections, we have already witnessed that leaders sometimes tried to intervene and make important decisions, and their actions were important subjective initiatives. One of the most important decisions was transforming from a planned economy to a market economy. Such a decision allowed further development of the productive force, and it was made based on an unsolvable conflict between the relation of production (planned economy) and an SOE system, which needs a more unrestricted flow of goods and exchange conditions. The transition would come naturally if there were no interventions from leaders, but the naturally occurring transition always involves chaos and disorder, just as the transitions from handicraft production to machine production have shown in Capital Marx [65]. In China’s transitions from plan to market, because of leaders’ interventions, the widespread disorders were avoided. Therefore, under the imposed limitations of productive force, using subjective initiatives to change the relation of production is very important, and that was what the CPC had done, especially during Xi’s period when he openly emphasised the importance of SOEs many times. It is essential to take notice of this argument in later discussions.

Throughout the entire reform process so far, the CPC has tried to insert subjective initiatives into economic management to establish a kind of economic system where the SOEs occupy the high ground, but private capital can join in and cooperate with the SOEs. The high ground that SOEs occupy will ensure the party’s leadership in the economic sector and serve as a base for a socialist market economy. As this situation develops, it could be foreseen that the party will try to direct both the public and private sectors to develop harmoniously. However, we have now seen that the economic system is in difficulties. It is natural to predict that there will be more difficulties in the future, and there has been no example for China to learn from. Combining what the CPC has done so far and the tool of historical materialism, the article proposes three possible conclusions about the future of SOEs, and they are all vital to the development of socialism in a future China.

The First Outcome

First, following the current trend of the development of productive forces of SOEs without any more interventions to the relation of production from the party. There will be many problems. One of them is the potential for less labor rights protection as well as more concessions to the expansion of capital in the future. The change of the SOEs from “whole-people” to “company limited” has already been the return of wage labor. No interventions in the future would result in more labour rights violations. In classical Marxist theory, the nature of a labor contract is an act of selling one’s labor force to owners of capital Marx [25]. Under “whole-people” ownership, workers were masters of the enterprises while the state performed its authority (imposed state plans) through workers. Meanwhile, under “company limited” ownership, the state is the runner of enterprises where workers perform the ownership through the state; the state becomes the master. It is argued that workers signing labor contracts with the socialist state are not “wage labor” because the state is socialist. However, such an argument only appears on paper, and there is neither severe punishment for violations nor supervision of how it is performed.

The signing of labor contracts will give enterprises full authority over workers. Also, cutting off labor’s welfare is one of the easiest ways to cut off a company’s expenses. We can confidently predict that when SOEs face difficulties in the future, in order to be responsible to the SASAC and other upper-level state organs and regulations, they might possibly cutting off the amount of profits that are used to purchase welfare services on the market because they do not need to be fully responsible for workers’ lives. Also, SOEs might have the possibility of demanding the lifting of the CPC’s regulations on them, which is a dangerous outcome for socialism in China. For example, SOEs might want to invest in areas such as finance, real estate, and other non-substantial economic sectors, which might increase their productivity in the short term while the current two structural difficulties will not be solved. With the disorder development of SOEs, despite the CPC still holding the basic policies such as the “two principles”, SOEs will be more and more similar to machines of profit-making. It is very clear that neither the problem of nei juan or the declining population would be solved by this outcome.

The Second Outcome

Second, slight adjustments and interventions toward the relations of production, and that is what the CPC has been doing. As we have reviewed, after the adoption of the market economy, there were only slight changes in the relations of production, and China has maintained sustainable growth in its economy for more than 30 years without significant changes in the relations of production. Adjustments, such as the setup of the SASAC, have been made. The mass privatisation of the 1990s was not a challenge to the fundamental market economy set up in 1992. As such a trend develops, there might be some more adjustments aimed at constructing market relations that can boost productive forces Zhang [66]. The state has already made some adjustments, such as “welfare-for-work,” trying to hire more workers, distributing coupons to encourage consumption, lifting some restrictions on the hukou system to allow more uneducated workers into cities, and so on. In these policies, the SOEs are the key actors of implementation; they need to act as vanguards in realizing these policies (Hangzhou Municipal Government [67]; National Development and Reform Commission [68]. It will generate positive effects, such as more people going into cities for jobs, more consumption, free labor power and capital flow, and so on. However, we cannot confidently argue that there is more potential under the current relation of production. Under the current relationship, SOEs are still mainly profit-making oriented actors in markets, and to what extent SOEs can sacrifice profits is still in question. As an example, it can be confidently argued that SOEs’ conduct “welfare-to-work” will increase workers’ income and job positions; however, when less profits for reinvestment has appeared, they will naturally want to stop such a policy, and a collective bargaining against the state policy is highly possible. Under this outcome, nei juan as well as low-income might be remitted for short time; but it will not solve them.

The Third Outcome

The third outcome is a practice of historical materialism, and through the lens of historical materialism, sometimes the relationship between the productive force and the relation of production should be considered more rigorously. The CPC has tried many times to intervene and influence productive force development within the limits set by productive force but has not yet fully realised its importance. Interventions are mostly slight adjustments. As an example, on the one hand, Xi [69] has mentioned the importance of public ownership, while on the other hand, the official tongue still says that: “The basic mission of socialism is to develop productive force, and it can not be changed at any time.” In the past, both Deng and Jiang Zemin have argued that productive forces are the key to socialism. As Jiang [70] has argued, in fighting for socialist modernity, the fundamental task is to achieve advance productive forces through reforms and developments. The importance of relations of production, however, has almost disappeared in official languages.

Intervening in the direction of the development of productive forces (inserting subjective initiatives) is a core idea in historical materialism and it has been forgotten for a long time. In the traditional Soviet interpretation, the idea of never intervening in the development of productive forces has dominated most of the socialist countries’ ideology including China for a very long time (Wang [71]; Zhu [72], it followed a wrong interpretation from the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy:

A social formation never disappears before all the productive forces that it is spacious enough to hold have been developed, and new, superior relations of production never take the place of the old ones before their material conditions have matured— blossomed at the heart of the old society. Marx [28]

This quote was cited in the Soviet book Dialectical and Historical Materialism, also known as the Soviet Bible, because it regards this sentence as “always-right” and ignores Marx’s many prerequisites before it. This quote reflects the idea of treating the development of productive force as the sole goal in economic development (wei sheng chan li lun). In most of the past reforms we have reviewed, the adjustments in relations of production were actions to serve the need to develop the productive force, and our first solution is an potential act of wei sheng chan li lun. However, as the Soviets demonstrated to the world in the 1990s, the only desire to develop the productive force resulted in an ossified nationwide bureaucratic structure and later became the obstacle to its socialist economy Beissinger [73]. Instead of making reforms in its economy, the Soviets never reformed its economic superstructure, and it unavoidably faced total collapse in 1991.

It is essential to demonstrate the importance of relations of production in playing its influences towards productive forces to avoid the Soviet conclusion. Louis Althusser believed that the arbitrary citation of the argument from Marx’s Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy in Dialectical and Historical Materialism reflected the idea of somewhat ossified logic in viewing the relations between the productive force and the relation of production. As Althusser [74] believed, “Within the specific unity of the productive force and relations of production constituting a mode of production, the relations of production play the determining role, based on and within the objective limits set by the existing productive forces.” Also, following Marxist ideals in The German Ideology, the productive force does play a decisive role in determining the relation of production. However, this “decisive” role does not mean “ultimate or absolute” Marx [24]. To avoid the wei sheng chan li lun, the key issue is to re-emphasise the importance of the relations of production as we have touched on in the theoretical sector: consider the limitations pre-decided by productive forces, relations of production sometimes set up for the framework for productive forces see Figure 2. If we go back to the “Past” and “Present” as well as summaries in “7.2.1” sections, CPC’s reforms and new regulations never gave up the dominance of the public sector as it is not only the key to socialist direction but also to the CPC’s dominance of power despite the party had made lots of concessions towards relations of production during the entire reform and opening up. In the past four decades, adjustments were enough for the development of productive forces. As for today, when economic depression approaches, the party might need to act more actively than before toward the relation of production instead of only making slight adjustments.

Current policies on solving economic difficulties will not change the nature of SOEs, and it is vital to present the third conclusion in detail. However, our blueprint will not fundamentally change the economic structure entirely because it is impossible to overthrow the economic system as we cannot break through the barriers set by productive forces. Nevertheless, there are several potential key pints. Low incomes and high prices for essential services such as real estate are among the most essential reasons behind population decline and neijuan. It is natural to conclude that lowering the cost of essential services will result in an easier life for laborers, and hence, their rewards would be enough to feed the next generations. Also, creating more demand in certain sectors will result in more job positions, and it will be a positive cycle generating more demands in other sectors. The most important issue is changing SOEs (at least central-governmentowned SOEs) from profit-making-oriented to social responsibilityoriented enterprises from central government regulations. It means that instead of investing in profitable sectors, SOEs might need to invest in areas such as social housing, infrastructure, and other sectors of substantial economy. By providing affordable houses with low rent, water, and gas to urban ordinaries, they would have more resources to engage in daily consumption. Also, in inner areas of China, millions of the population who are living in rural or urban peripheries have not enjoyed urban life or live in relative poverty. The task of increasing their living standards is itself a mission that will generate huge demand for production as well as investments in substantial economy.

The increase in demand would result in more production, and more production would result in more job positions as well as more profits for reinvestment and more material benefits/ incomes for workers’ enjoyment. By doing so, SOEs’ primary tasks should no longer focus on capital/assets management, even if they are against market rules. To say this more directly, a market relationship might need to mix with state planning in certain areas, and some of the most basic services should be put under direct planning and distribution. However, centralised planning would also lead to ossified management, and the party should use the advantages of central planning, such as collecting and investing resources into specific sectors in a very short period. When resources are in place, markets or other mechanisms can be brought into balance against disadvantages of central planning. It is time to make another change in the relationship of production; only by doing so we can solve two major difficulties in economy. However, this change is merely a proposal based on objective limitations set by productive forces. We can confidently argue that the third conclusion will not only consolidate the current position of SOEs in the national economy but also will pursuit an overall better life for most of the Chinese people [76-80].

Conclusion

In conclusion, in order to solve the puzzles proposed in the introduction, instead of providing a brief overview of history, this article is an analysis of the logic behind the entire reform process. Instead of viewing the reform process as policy changes at the leader’s will, this article argues that the reform of SOEs results from interactions between productive forces and relations of production. Through the lens of historical materialism, productive forces always play a determining role in deciding the reforms in relations of production. Leaders’ will play a noticeable role, but they cannot override the development of productive forces. In the end, the article argues about the future of China’s SOEs. After decades of fast development of the productivity of SOEs, the current Chinese economy has met its structural difficulties. Instead of fully following productive forces’ development, more subjective actions should be taken to influence the direction of the development of productive forces. This article finally argues that some planning mechanisms should be brought back in based on current production forces.

References

- The State Council of the PRC (1988) Constitutional Amendment of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China. The Constitutional Amendment of the People’s Republic of China. In 1988 Gazette of the PRC. Beijing pp. 359-360.

- Central Committee of the CPC (1993) Decision of the Central Committee of the CPC on several questions concerning the establishment of a socialist Market economic system. Beijing: The Central Committee of the CPC.

- Chen YJ (2021) The assets of state-owned enterprises account for 56% of the total assets of enterprises in China - based on the fourth Economic Census yearbook data], Economic Observers.

- Lin C (2006) The Transformation of Chinese Socialism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Frazier M (2002) The Making of the Chinese Industrial Workplace: State, Revolution, and Labor Management. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Chen ZW (2016) A Century of lament: Charting the political history of Chinese workers]. In M. M. Chen, G. S. Bao, & Y. Chen, Y. Chen (Eds.), Fudan political science review–labor politics 16: 96-112. Fudan University Press.

- Zhang DC (2020a) The Annals of China’s State-Owned Enterprises Reform. Beijing: China Workers’ Press Volume 1-4.

- Wang LF (1989) How to Understand the Essences of the Whole-people’s Ownership. Financial Issue Studies (Z1): 70-74.

- Zhang XX (2016) Re-exploring the Danwei System in the Context of Industrialism]. Shandong Social Science 6: 57-62.

- Bell D (2015) The China Model. New York: Princeton University Press.

- Garnaut R, Song LG, Yao Y (2006) Impact and Significance of State-Owned Enterprise Restructuring in China. The China Journal 55: pp. 35-63.

- Oi JC (2005) Patterns of Corporate Restructuring in China: Political Constraints on Privatization. The China Journal 53: 115-136.

- Yu H (2013) The Ascendency of State-owned Enterprises in China: development, controversy and problems. Journal of Contemporary Asia 85(23): 161-182.

- Yu H (2019) Reform of State-owned Enterprises in China: The Chinese Communist Party Strikes Back. Asian Studies Review 43(2): 332-351.

- Zhang XW (2023) Is China Socialist? Theorising the Political Economy of China.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 53 (5): 810-827.

- Weber IM (2021) How China Escaped from Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lin C (2013) China and Global Capitalism: Reflections on Marxism, History, and Contemporary Politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harvey D (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Huang YS (2008) Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Li SM, Li SH, Zhang WY (2000) The Road to Capitalism: Competition and Institutional Change in China. Journal of Comparative Economics 28(2): 269-292.

- Ma SY (1998) The Chinese Route to Privatization: The Evolution of the Shareholding System Operation. Asian Survey 38(4): 379-397.

- Smith R (1999) The Chinese Road to Capitalism. New Left Review 199(1).

- Marx K (1887a) Division of Labor and Manufacture, in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy p. 1.

- Marx K (1932) The German Ideology: Critique of Modern German Philosophy According to Its Representatives Feuerbach, B. Bauer and Stirner, and of German Socialism According to Its Various Prophets. In Marx-Engels Collected Works p. 5.

- Marx K, Enegels F (1849) Effect of Capitalist Competition on the Capitalist Class the Middle Class and the Working Class. In Wage Labor and Capital. Berlin: Neue Rheinische Zeitung.

- Marx K (1959) Estranged Labour, in Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Marx K (1969) Position of the communists in relation to the various existing opposition parties. In K. Marx (Ed.), On Manifesto of the Communist Party, Marx and Engels selected works. Progress Publishers p. 1.

- Marx K (1977) The Preface. In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Li Y (2019) The First Five-Year-Plan’s 156 Programs. In Li Y. The Power of Detail: The Great Practice of the New China. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Press.

- Marx K, Engels F (1852) The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (Chapter 1). New York: Die Revolution.

- Marx K (1871) The Paris Commune. In The Civil in France. London: Zodiac & Brian Baggins.

- Shi CL (2016) Revision on the Three Major Issues of “si ma fen fei. Journal of CPC History 8: 117-122.

- Mei H (2013) How to correctly evaluate the two 30 years before and after the reform and opening up. In CPC Membership Net.

- Schrumann F (1968) Ideology and Organization in Communist China. Los Angels: University of California Press.

- Walder A (1984) Communist neo-traditionalism: Work and authority in Chinese Industry. University of California Press.

- Deng XP (1983) The Speech on the Opening Ceremony of the National Science Conference. In Deng Xiaoping Selected Works (1975-1983). Beijing: People’s Publishers.

- Deng XP (1989) [On How to Recover Agriculture Production]. In Deng Xiaoping Selected Works (1938-1965). Beijing: People’s Publishers.

- Deng XP (1993) Key Points on the Speech at Wuchang, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shanghai, and Other Places. In Deng Xiaoping Selected Works (1982-1992). Beijing: People’s Publishers.

- Central Committee of the CPC (1981) Resolutions on certain historical questions of the Party since the founding of the People's Republic. In The Central People’s Government website.

- Central Committee of the CPC (1984) Decision of the Central Committee of the CPC on economic restructuring. In The Central People’s Government website.

- Central Committee of the CPC (1993).

- The Eighth Congress of the National People’s Congress of the PRC (1993) Company Law of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing.

- The State Council of the PRC (1988) The Law of Whole-people’s Industrial Enterprise of the People’s Republic of China. The Constitutional Amendment of the People’s Republic of China. In 1988 Gazette of the PRC. Beijing pp. 363-371.

- (2023) State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC).

- Central Committee of the CPC (2003) Decision of the Central Committee of the CPC on several issues concerning the improvement of the Socialist Market economic system. In The Central People’s Government website.

- Zhang DC (2020c) Establish and improve the management and supervision system of state-owned assets]. In Zhang DC: 1978-2018. The Annals of China’s State-Owned Enterprises Reform, Beijing: China Workers’ Press pp. 1069-1078.

- Zhang DC (2020b) 1988, The Background. In Zhang DC 1978-2018. The Annals of China’s State-Owned Enterprises Reform, Beijing: China Workers’ Press p. 2.

- Zhang DC (2020d) 1988, Major Reform Policies. In Zhang DC: 1978-2018. The Annals of China’s State-Owned Enterprises Reform. Beijing: China Workers’ Press p. 2.

- Lin C (2021) Revolution and Counterrevolution in China: The Paradoxes of Chinese Struggle. London: Verso.

- State Statistical Bureau (1985) Economic Statistical materials on Chinese Industry 1949-1984. China Statistics Press.

- State Statistical Bureau (1987) Economic Statistical materials on Chinese Industry. China Statistics Press.

- State Statistical Bureau (1989) Economic Statistical materials on Chinese Industry. China Statistics Press.

- (2023) The World Bank, The GDP Growth Rate.

- (2017) State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC). A three-year action plan for State-owned Enterprise reform.

- Zhang DC (2020e) (2017) Annual Reform Practices. In Zhang DC: 1978-2018. The Annals of China’s State-Owned Enterprises Reform. Beijing: China Workers’ Press p. 4.

- Guo SJ (2010) The Ownership Reform in China: What direction and how far. Journal of Contemporary China 36(12): 553-73.

- Central Committee of the CPC (2020) The Meeting of The Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee], Beijing.

- Liang X (1985) Whole-people’s Ownership and Economic Reforms. Journal of Anhui Normal (Philosophy and Social Science 1: 16-20.

- Li HF (2020) A Brief Analysis on the Change of Ownership of State-Owned Enterprises. Hebei Enterprises 4: 113-114.

- Zhang DC (2020f) The root cause of the real economy recession. In Zhang, D.C: 1978-2018. The Annals of China’s State-Owned Enterprises Reform. Beijing: China Workers’ Press p. 4.

- National Bureau of Statistics (2023) National Survey of Urban Unemployment Rate]. In National Bureau of Statistics, Monthly Data.

- Larmer B, Zhang J (2023) China’s population is shrinking. It faces a perilous future”, National Geographic.

- Tian YJ (2023) For family and country: why China needs more babies.” South China Morning Post.

- Marx K (1887b) The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation, in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy p. 1.

- Marx K (1887c) Money, Or the Circulation of Commodities, in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy p. 1.

- Marx K (1887d) Machinery and Modern Industry, in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy p. 1.

- Zhang DC (2020g) 1993, Important Theoretical Points. In Zhang1978-2018. The Annals of China’s State-Owned Enterprises Reform. Beijing: China Workers’ Press p. 2.

- Hangzhou Municipal People’s Government (2023) Zhejiang province (except Hangzhou city) has abolished all restrictions on household registration. Zhejiang Government Website.

- National Development and Reform Commission (2023) State Administration of welfare-for-work. Beijing: Regulations of National Development and Reform Commission.

- Xi JP (2020) Adhere to historical materialism and constantly open up new horizons for the development of Marxism in contemporary China. Hongqi (2): 1-3.

- Jiang ZM (2001) Speech at the celebration of the 80th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China. In Jiang Zemin Selected Work Beijing: People’s Publishers p. 3.

- Wang NN (2018) The history and fate of capitalism can be seen from the conclusion of "two will be" and "two nevers. Legal and Society (5): 234-235.

- Zhu BY (2019) “Two Will Be” is still the general trend of today's world development]. Hongqi 6: 17-20.

- Beissinger MB (1988) Scientific management, socialist discipline, and Soviet power. Harvard University Press.

- Althusser L (1971) On the Primacy of the Relations of Production over Productive Forces, in Althusser, L. On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State. Apparatuses. London: Verso 1971: 209-210.

- (1993) Communique of the Third Plenary Session of the 14th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China.

- Gong XK (1994) On Whole-people’s Ownership’s History and Contradictions. Learning and Exploration 2: 4-11.

- Hell N, Scott R (2020) Invisible China: How the urban-rural divide threatens China’s Chicago University Press.

- Su S (1998) Analysis of The Theory of the Primary Stage of Socialism. Modern China Studies.

- Tian YP (2016) Danwei System and Industrialism. Xuehai (4): 63-75.