Methodological Approaches in Public Policies: Relevance of Analysis in the Context of Good Governance

Alexandre Morais Nunes1* and João Ricardo Catarino2

1Centre for Public Administration and Public Policies, Institute of Social and Political Sciences, Universidade de Lisboa, Rua Almerindo Lessa, 1300-663, Lisbon, Portugal. ORCID: 0000-0002-6808-7769

2Centre for Public Administration and Public Policies, Institute of Social and Political Sciences, Universidade de Lisboa, Rua Almerindo Lessa, 1300-663, Lisbon, Portugal. ORCID: 0000-0001-9372-083X.

Submission: February 11, 2024; Published: February 26, 2024

*Corresponding author: Alexandre Morais Nunes, Centre for Public Administration and Public Policies, Institute of Social and Political Sciences, Universidade de Lisboa, Rua Almerindo Lessa, 1300-663, Lisbon, Portugal

How to cite this article: Alexandre Morais Nunes* and João Ricardo Catarino. Methodological Approaches in Public Policies: Relevance of Analysis in the Context of Good Governance. Acad J Politics and Public Admin. 2024; 1(2): 555559. DOI:10.19080/ACJPP.2024.01.555559.

Abstract

In the rule of law, public policies are increasingly seen as fundamental determinants of good governance. The present study aims to present the importance of analyzing public policies as a means to improve the governance process. Based on the literature review, public policies were characterized, and a comparative analysis was made of the main theoretical study models, with greater emphasis on the understanding of public policies that start from the idea of a public problem, with the intention to search for a solution. As a result, it appears that there are different models, each of them reflecting its own analytical perspective, which can complement each other and adapt to the context of the policy itself, aligned with the structural principles of good governance. It is, therefore, concluded, on the one hand, that the public policy process can be analyzed from different perspectives: with a view to its construction or reformulation, with an analysis model based on a conceptual framework that best suits the concrete characteristics of each policy or the purposes for which it was established. On the other hand, it appears that there is a parallel between the success of public policies and respect for the principles of good governance by the public administration.

Keywords: Public policies; Policy analysis; Good governance

Abbreviations: ACF: Advocacy Coalition Framework; IMF: International Monetary Fund; UN: United Nations; EU: European Union; OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; ADB: Asian Development Bank

Introduction

Public policies represent a set of government actions, decisions, and initiatives that aim to analyze specific issues that can cover a wide range of areas, from social well-being, economic development, finance, education, health and environment, among others [1]. According to Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl [2], the government is the central actor in matters of public policy, namely through the choice it takes on a given path (priority intervention over another) or non-intervention, which is normally conscious and not an absence of action. They can also be defined as “government action or inaction in response to public problems” in the sense of Michael Kraft & Scott Furlong [3], Subirats et. Al [4], Knoepfel et al. [5] and Cardoso [6]. Public policies constitute complex and multidimensional processes, which develop on multiple levels of action/decision, whether at local, regional, national, or transnational levels. They can take the form of laws, regulations, programs, and initiatives designed to influence or control certain aspects of public life, always with the ultimate objective of promoting the well-being of citizens, addressing social challenges, and promoting the common good [1]. These policies are considered essential to establish a framework that guides the actions of the government, citizens, and all other public/private entities and involves different actors, from government officials, legislators, voters, public administration, and interest groups which aim to solve public problems and promote the distribution of power and resources [7].

The development of public policies is a continuous process that involves various actors, from political decision-makers to public opinion and other interested parties. It also takes into account available resources, legal restrictions, economic considerations, social needs, and the expected impact on society [1].

Public policies can also be categorized in different ways, depending on different criteria and associated dimensions, such as the following:

i. In terms of purpose, public policies can be proactive, aiming to face emerging challenges, or reactive, responding to existing problems.

ii. Regarding the area, they can adopt, for example, the form of economic policies (they address issues related to economic development, fiscal and monetary policies, taxation, trade, and employment); social policies (focus on social issues (health, education, well-being, housing, poverty); environmental policies (aim to manage and preserve natural resources, combat pollution and promote sustainable practices);

iii. Regarding the scope, they can be constituted as macro policies (Address broad issues at a national level), meso policies (Target specific sectors or industries), or micro policies (Address local issues, communities, or specific groups);

iv. Regarding the approach, they may appear as regulatory policies (aim to regulate and control various activities to provide guarantees), redistributive policies (aim to reduce economic and social inequalities through mechanisms such as progressive taxation and social welfare programs), or development policies (focus on economic growth, innovation, and infrastructure development);

v. In terms of duration, policies can be permanent (aim to be lasting and consistent in the long term) or temporary (aim to address specific issues or crises with a fixed term);

vi. Regarding the target population, they can take the form of universal policies (apply to the entire population without discrimination) or targeted policies (focus on the needs of certain groups) [1,8-10].

Regardless of the classification assigned, the effectiveness of a public policy is often analyzed through continuous evaluations and adjustments to ensure that it meets its intended objectives [1]. It is in this segment that it stands out in the analysis of public policies. The concept of policy analysis was introduced by Lasswell in 1948 when he developed an alternative to the traditional objects of study of political science, which until then focused on the study of constitutions, issues of classical power, legislatures, and groups of interest. However, in the 1950s, in addition to Lasswell, other authors such as Herbert Simon, Charles Lindblom, and David Easton stood out in this area, contributing to the study of public policies becoming autonomous as an autonomous scientific area [11-13]. Starting from a base of political science, psychology, sociology, economics, and the study of organizations, the development of this field of studies, since the 1950s, has given rise to a multidisciplinary area that allows explaining and thinking about public policies, understanding the functioning of public action, analyzing the factors of continuity or rupture, and understanding the interaction of actors and institutions in political processes. In other words, it is through policy analysis that it is possible to study political decisions and government actions, from the origin of the problems they set out to solve to the solutions found, as well as how they were implemented and their respective conditions (favorable or not) [7,14].

Based on the principles of Lasswell, Simon, Lindblom, and Easton several theoretical models for analyzing public policies were developed. The following are presented and characterized: 1) the sequential or political cycle model; 2) the multiple streams model; 3) the interrupted equilibrium model; 4) the theoretical framework of cause or interest coalitions, and the trash can model. These models are logically more coherent and comprehensive, based on verifiable empirical propositions, and more used in the literature [13,15,16], given their adaptability and replicability in different contexts. Furthermore, what all these models have in common is the fact that they started from the idea of a public problem with the intention of finding a solution. However, even though they have the same purpose, they are guided based on different assumptions that distinguish them.

The sequential or political cycle model

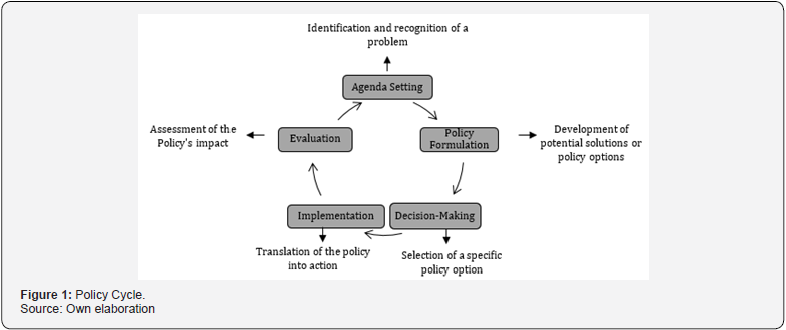

In the sequential model, based on the stage model initially proposed by Laswell, public policies are constructed grounded on a linear process developed in stages around a political cycle that repeats itself [7] (Figure 1).

Although the policy construction process itself can be dynamic and subject to factors that manifest themselves in different ways, this approach provides a structured way of conceptualizing these phases, starting from scheduling (identifying a problem that requires attention from a government); going through formulation (development of solutions or policy options to resolve the identified problem); decision making (selection of the most relevant/functional option); through implementation (moving to action, in which the policy is put into practice) and ending with evaluation (in terms of the impact on the expected results given the problem initially raised) [13,16]. The model aims to contribute to the discussion on the difficult and complex relationship between social, political, and economic environments and government action in all phases of public policies, that is, on the relationships between governmental and non-governmental actors in the process of policy globally considered. In this way, public action aimed at solving problems is analyzed as a sequential and unfinished process that is reconstructed depending on changes in the context or the results of the policies themselves [13]. The idea of a policy cycle encompasses the activities of diagnosis (a project), ex ante evaluation (modifications to the project), implementation, evaluation, and, where applicable, conclusion, which should determine the ex-post or impact evaluation.

The multiple streams model

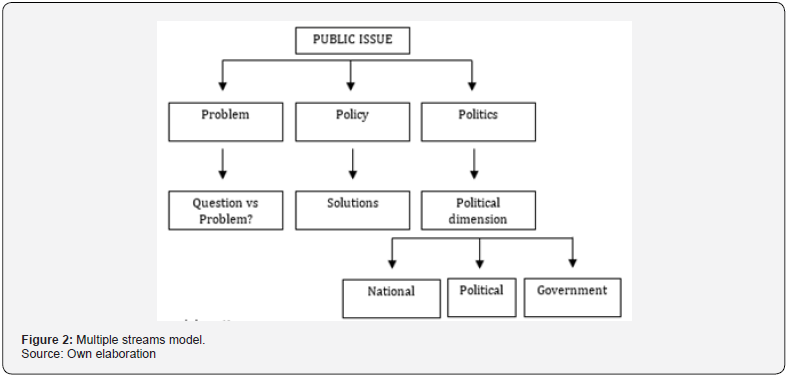

The multiple streams model proposed by John Kingdon identifies three streams that converge to create windows of opportunity for political change: the problem stream (associated with public perception); the flow of policies (associated with the knowledge of appropriate solutions), and the flow of policy (associated with governance conditions). In other words, policies advance when flows align [10,17] (Figure 2). In this model, for Kingdon, the flow of problems is associated with existing issues that may not exactly constitute a political problem, meaning that an issue only becomes a problem when political decision-makers understand that a solution must be found. In turn, the policy flow is made of alternatives/solutions to a problem, we will call it a set of ideas. Sometimes, a solution may need to be created prior to the problem. The policy flow is associated with the policy dimension that follows a course independent of the problem. However, it is sensitive to three variables: national sentiment (ideas shared by a large part of the population); pressure from political forces (parties and interest groups), and government changes, whether due to a change in the political cycle or remodeling carried out [10].

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory

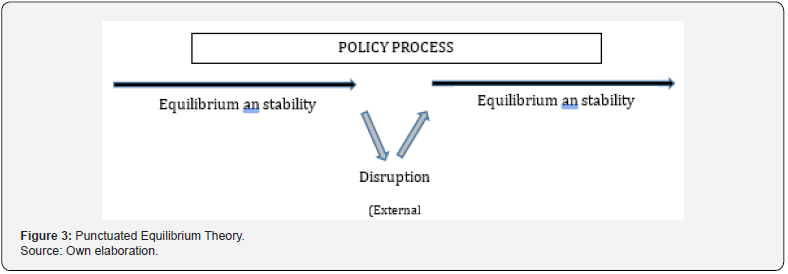

The punctuated equilibrium model was developed by Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones and challenges the traditional view of political change as a gradual, incremental process. On the other hand, it suggests that policies tend to remain stable over long periods (equilibrium), marked by brief periods of rapid change (giving rise to the concept of punctuated). In other words, it is based on the principle that political processes are characterized by stability and incrementalism but considers occasional/punctual changes that interrupt this cycle [18,19] (Figure 3). This model considers the dimension of political balance (once established, policies tend to remain stable for long periods, focused on the principle of bounded rationality) and the dimension of change (which interrupts stability and, as a rule, is associated with sudden and unforeseen events), triggered by External shocks (such as changes in political leadership and public opinion, crises or new information that challenges existing political assumptions), which lead to readaptation through learning and adaptation, which in turn leads to a new balance. In this process, the concept of political image is central and emphasizes the role of political subsystems (communities, interest groups) [18,19].

Advocacy Coalition Framework

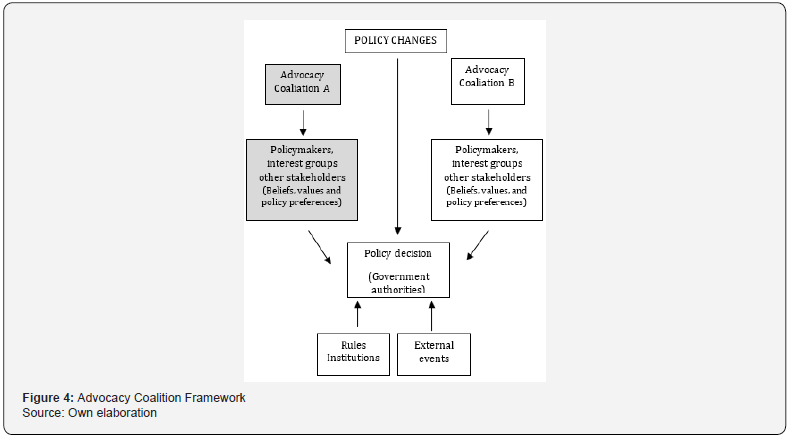

The Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) developed by Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith focuses on the dynamics of political subsystems in which actors or organizations act to influence political development in a given area [20,21] (Figure 4). Those involved in the political process share common beliefs and values related to a specific policy. Thus, when acting in tandem, they form a coalition of cause or interest (an advocacy coalition) intending to cause changes in policies by influencing the decision-making. However, there are different coalitions, and, therefore, the model foresees the existence of policy brokers to try to reach consensus/grant the different coalitions in the search for high degrees of consensus (long-term coalition opportunity structure), for which two sets of variables are worked on: stable (rules, institutions, political system) and unstable (external and unforeseen events such as changes in government, institutions, society, or economy) [20,21].

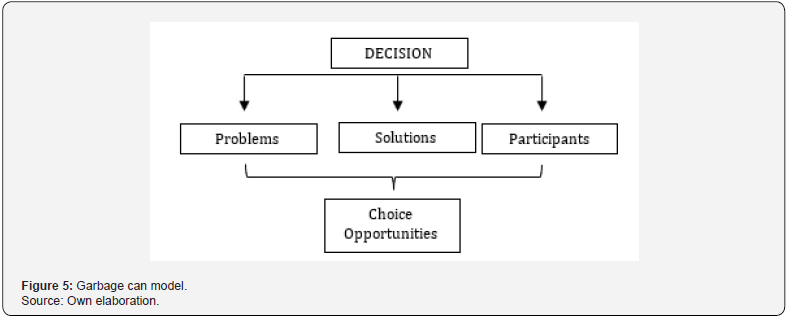

Garbage Can Model

The Trash Can Model, also known as the Trash Can Theory of Decision Making, is a theoretical model developed by Michael D. Cohen, James G. March, and Johan Olsen in the early 1970s, which aims to explain the complexity and unpredictability of decisionmaking processes [18] (Figure 5). The model moves away from the traditional rational decision-making approach and highlights the chaotic and non-linear nature of decision processes, stating that a decision is an outcome or interpretation of several relatively independent flows within an organization [18]. The success of structuring, implementing, and evaluating public policies depends on the quality of the existing Governance framework. The quality of these two realities is reflected both in the way they interact with each other, and in the way they design, implement, and solve public problems, focusing on satisfying collective needs and building happier societies. However, it has not been easy to reach a consensus on a concept of good governance, partly as a result of its inherent complexity and, on the other hand, as a result of the fact that it is a plastic concept, capable of meaning different things depending on the perspective of the entity that carries it out [22].

The concept of good governance was boosted in the 1990s through the development agenda of major international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU), and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Good governance has since developed in a context of soft power [23] and in an environment of economic and democratic openness on a global scale through two large sets of constraints, namely: those resulting from the so-called ‘Consensus Washington’ and ‘good governance’ [24,25]. Thus, for example, the World Bank came to define good governance as a strategy for action in the economic and social field to adopt more efficient, economical, and effective management practices to satisfy collective needs.

The concept of governance is not unequivocally delimitable. In fact, depending on the perspective adopted, it is understood in different ways by different entities, depending on the sociopolitical environment where the objectives are set. For example, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) understands governance as “the way in which power is exercised in managing the economic and social resources of a state, with a view to its development”. The World Bank refers to governance as the set of traditions and institutions through which authority in a country is exercised [26,27]. Whether the IMF, the UN, the OECD, and the European Commission itself present different dimensions of good governance, which academia has been complementing, as is the case with studies by Weiss [28], Boivard and Loeffler [29,30] or by Stoker [31], to which we refer.

Results and Discussion

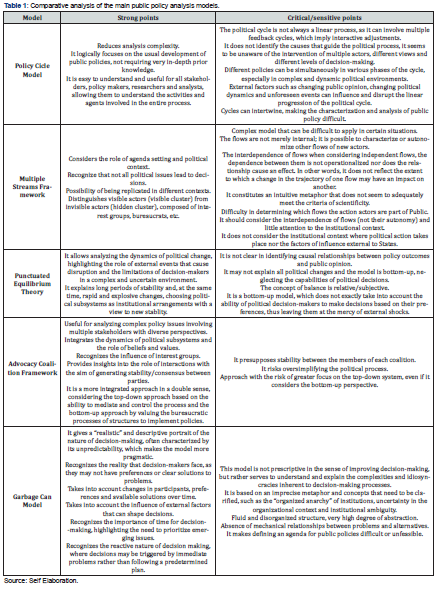

In order for public policies to have a positive impact on governance and reflect their importance in a social state model, they must be analyzed in accordance with existing theoretical models. These, in turn, could lead to the extinction or reformulation of the policy and, consequently, to the construction of a new policy based on the analysis of the previous policy. The question thus arises: what is the best model for the study and analysis of public policies? And what is its importance in the context of public governance? On this basis, in response to the first question and supported by the literature presented in the previous point, a comparative analysis of the main theoretical models used in the study of public policies was developed, presenting their main advantages/disadvantages (Table 1).

In response to the second question, observing the characterization of public policies and their analysis processes and taking into account that good governance is a concept that encompasses the principles and practices that contribute to an effective, responsible, and transparent management of public affairs [32], it is possible to identify that we are faced with realities that are interconnected, insofar as both contribute to the proper functioning of the State and the well-being of society. There is, therefore, a stable and consequent relationship between the concepts at the level:

i. Decision/decision-making: Since the actions and decisions taken by governments are formulated through structured policies that involve phases that, transversal to the different models, involve a component of problem identification, analysis, and development of considered solutions. In turn, at the level of good governance, decision-making processes arising from policies are expected to be responsible, participatory, inclusive, and transparent, respecting different interests and perspectives.

ii. Implementation/provision of services: To achieve the objectives set out in the formulation, policies need to be implemented effectively, involving resources and the need for good governance that guarantee the provision of services in a fair and timely manner across entities /services, efficiently with due transparency and accountability in the use of public resources.

iii. Citizen participation: Public policies must listen to citizens and understand their needs, and good governance must actively involve citizens in decision-making and monitoring, collecting their feedback, thus ensuring that political measures meet the needs problems/needs identified.

iv. Sense of State: Both policies and good governance respect the rule of law, the legal framework.

v. Monitoring and evaluation: On the one hand, public policies require regular analysis/evaluation to make the necessary adjustments; good governance must also include monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to ensure the good application of public resources and that policies are adapted based on these mechanisms.

The elements found regarding the strengths and weaknesses of the different models allow us to verify that none are perfect and that none are unprofitable. They all start from different assumptions and all constitute proposals to explain public action. They all have their relevance, depending on several factors and how one intends to approach the process of the most varied policies and, sometimes, depending on the adoption of the more rational or incrementalist analysis model. These results are in line with what is found in the literature, particularly in terms of analysis of the public policy process, where it is interesting to verify the fact that the authors of the models presented continually criticize previous models, see:

i. Parsons [9] criticized the political cycle model, saying that it is not a causal model and that it could not be empirically tested. The same author adds that this model, by favoring a topdown approach, ignores the diversity that exists at different decision levels.

ii. In the same line of thought, Kingdon [10] understands that the political cycle model makes a mistake when considering that the political process occurs in an orderly manner. Thus, this author clearly rejects and criticizes the phases of the cycle, arguing that the scheduling of public policy does not necessarily occur first and that, on the contrary, alternatives exist and are considered before the agenda demands it.

iii. Sabatier [13], like Parsons [9] does not identify the guiding causality of the political process defended by Laswell and the fact that by focusing on a cycle the dynamics of interaction between multiple decision levels are lost, which would certainly give rise to different proposals for solution, greater diversity of actors and more consequential policies.

iv. According to Muller [16], and Araújo and Rodrigues [7], the policy cycle model is heuristic and, as such, explores public policies with an analytical objective through a basic representation of reality, transforming it into a rational structure. In this way, they perceive the model as fundamental to understanding the continuous flow of policies, even though they warn that it should not be used mechanically.

v. Sabatier and Schlager, [33] although aligned with Kingdon’s model, highlight the centrality given to information, the focus on the socioeconomic component, and the possibility of being replicated in different scenarios. However, they criticize the model for its limitation in providing a methodology that allows determining which flows political action actors could be integrated into. The authors state that the mechanisms could be clearer and simplify the policy formulation process by presenting it as a linear and sequential set of events and pointing out the difficulty in finding windows of opportunity.

vi. John [34] focuses his criticism on the punctuated equilibrium model because it is basically bottom-up and, thus, loses the ability of decision makers to shape decisions, meeting their preferences. On the other hand, this author emphasizes that the methodology used in this model establishes associations and not causal relationships between policy results, public opinion, policies, and other stakeholders such as the media.

vii. According to Parsons [9], the Advocacy Coalition Framework model is considered very useful to guide empirical research on policy implementation. As an example, Parsons [9] reports that this model was used with good results to analyze a wide range of cases in the USA and Europe.

viii. Zahariadis [35] points out that the multiple streams model can also predict changes in the agenda and that, with this, it can influence the composition of the political agenda as well as the public problems that arise in the political arena and the public policy agenda.

ix. Mucciaroni [36] argues that they are not, in practice, independent. The dependence between them, he argues, would help to reduce its random character and make it more strategic and intentional. He suggests that the model be developed to highlight how events in a given flow influence events in other flows.

x. Concerning the Garbage Can model, Zahariadis [35] understands that the independence of flows is an advantage that allows it to maintain its logic intact and, therefore, a different perspective to rationalist models.

Conclusions

Public policies concern actions, decisions, and strategies developed and implemented by bodies of a public nature, which aim to solve a relevant public problem through rational decisionmaking, with the purpose of modifying or directing the behaviors of specific groups dimensions in the most varied dimensions, examples being social, economic and environmental, whether from a local, regional, or national perspective, and to impact the social and political system. Most of the time, public policies result from complex processes that involve several phases and different actors and involve political decision-making with complex purposes, not always to the satisfaction of citizens. In these processes, the elements inherent to all policies cannot be dispensed within their construction processes. Therefore, the design of any and all policies must also include, in addition to the elements mentioned above, goals and objectives since they, by definition, aim to produce impacts on the social and political system [37,38].

Public policies must be equipped with instruments (political, legal, or other) that make them effective, which usually happens in the form of laws, regulations, incentives, programs, or taxes, with the collaboration of stakeholders, including the different government agencies to implement and monitor them. Public policies cannot ignore whether they focus on citizens in general or specific groups. In short, the development and implementation of public policies plays a crucial role, as it is through them that the general behaviors or behaviors of specific groups are modified or directed and established based on rational decisions and measures necessary for implementation. In fact, although the core of public policies is the decision, strictly speaking, these do not exist if there are no implementing measures. Therefore, all decisions must be accompanied by implementation measures [39].

Thus, given the relationship between the concept of good governance, public policies, and society, the importance of the public policy process in the governance process is clear, given that through these, the priority measures are determined, the fulfillment of programs/strategies role of each agent and legislate, and define specific measures to meet priorities, and establish a set of commitments and strategies to guide decision-making, combining consensus between political objectives and the needs of the population. Ultimately, it can be concluded that the values and principles inherent to the concept of good governance provide a relevant theoretical basis for the development and implementation of effective and efficient public policies. When put into practice adopting principles of good governance (e.g. transparency, accountability, citizen participation, and the primacy of the rule of law), public policies fully satisfy collective needs and materialize socially relevant values for the construction of richer, more inclusive, and socially fairer societies, increasing levels of well-being and happiness.

References

- Hill M, Hill M, Varone F (2016) The Public Policy Process. (7th), Routledge, London, United Kingdom pp. 1-400.

- Howlett M, Ramesh M (2009) Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems. (3rd), Oxford University Press, United Kingdom pp. 1-336.

- Kraft M, Furlong, S (2015) Public Policy: Politics, Analysis, and Alternatives. (5th), Sage/CQ Press, Washington, United States of América pp. 1-568.

- Subirats J, Knoepfel P, Larrue C, Varone F (2008) Análisis y gestion de políticas pú (1st Ed.), Ariel, Madrid, Spain pp. 1-501.

- Knoepfel P, Larrue C, Varone F, Hill M (2007) Public policy analysis. (1st ), Policy Press, London, United Kingdom pp. 1-327.

- Cardoso R (1997). Terceiro setor: desenvolvimento social sustentado. (1st ), Paz e Terra, São Paulo, Brazil pp. 1-175.

- Araújo L, Rodrigues, ML (2017) Frameworks of public policies analysis. Sociologia,Problemas e Práticas 83(1): 11-35.

- Steinberger P (1980) Tipologias of public policy: meaning construction and the policy process. Social Science Quartel 61(2): 185-197.

- Parsons Wine (1995) Public Policy. An Introduction to the Theory and Pratice of Policy. Analysis. (1st), Edward Elgar Cheltenham, United Kingdom pp- 1-704.

- Kingdon JW (2011) Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. (Updated 2nd), Longman, Boston, United States of America pp.1-308.

- Fisher F (2003) Reframing Public Policy. Discursive Politics and Deliberative Pratices, Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom pp.1-278.

- Hill M (2009) The Public Policy Process. (ª Ed.), Pearson Education, Harlow, United Kingdom pp. 1-352.

- Sabatier PA (2007) Theories of the Policy Process. (1st ), Westview Press, Boulder, United States pp. 1-220.

- Lindblom C, Woodhouse E (1992) The Policy-Making Process. (3rd ), Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, United States of America pp. 1-176.

- Birkland TA (2019) An Introdution to the Policy Process, Theories, Concepts and Models of Public Policy Making. (5th), Routledge, London, United Kingdom pp. 1-448.

- Muller P (2010) Les Politiques Publiques. (ª Ed.), Presses Universitaires, Paris, France pp. 1-128.

- Zahariadis N (2007) The multiple streams framework. In: Sabatier (Eds), Theories of the Policy Process. (1st), Westview Press, Boulder, United States p. 65-92.

- True J, Jones B, Baumgartner FR P (2007) Punctuated-Equilibrium Theory: Explaining stability and changes in public policymaking. In: Sabatier (Eds), Theories of the Policy Process. (1st ), Westview Press, Boulder, United States pp. 155-188.

- Baumgartner FR, Foucault M, François, A (2012) Public budgeting in the EU Commission: a test of the Punctuated Equilibrium Thesis, Politique Europpéenne 38(1): 70-99.

- Weible C, Sabatier P, (2007) The Advocacy Coalition Framework. In: Weible C, Sabatier P (Eds), Theories of the Policy Process. (4th), Westview Press, Boulder, United States pp. 189-211.

- Sabatier P (1998) The Advocacy Coalition Framework: revisions and relevance for Europe. Journal of European Policy 5(1): 98-130.

- Cohen M, March JG, Olsen J (1972) A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice. Administrative Science Quarterly 17(1): 1-25.

- Nye J (1990) Soft Power. Foreign Policy 80: 153-171.

- Diarra G, Plane P (2014) Assessing the World Bank's influence on the good governance paradigm. Oxford development studies 42(4): 473-487.

- Sindzingre AN (2014) The Limitations of Conditionality: Comparing The ‘Washington Consensus’ and ‘Governance’ Reforms. HAL Science Ouverte. Lisbon Conference’, Portuguese Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, ISCTE-Lisbon University, Portugal.

- Baldi B (1999) Beyond the federal-unitary dichotomy. Institute of Governmental Studies, University of California, Berkeley, United States of America pp. 99-107.

- Peters BG (2012) Governance as political theory. In: Yu J, Guo S (Eds.), Civil Society and Governance in China, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, United States of America p. 17-37.

- Weiss T, Thakur R (2010) Global Governance and the UN - An Unfinished Journey. (1st), University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Indiana, Indiana, United States of America pp. 1-420.

- Bovaird T, Loeffler E (2003) Evaluating the quality of public governance: indicators, models and methodologies. International Review of Administrative Sciences 69(3): 313-328.

- Bovaird T, Loeffler E (2016) Public Management and Governance. (3rd), Routledge, London, United Kingdom pp. 1-446.

- Stoker G (1999) Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal 50(1): 17-28.

- Council of Europe (2008) 12 Principles of Good Governance. https://www.coe.int/en/web/good-governance/12-principles

- Sabatier P, Schlager E (2000) Les approches cognitives des politiques publiques: perspectives américaines, Revue Française de Science Politique 50(2): 209-234.

- John P (2012) Analyzing Public Policy. (2nd ), Routledge, London, United Kingdom pp. 1-224.

- Zahariadis N (1999) Ambiguity, time and multiple streams. Theories of the policy process. In: Sabatier P A. (Ed.) Theories of the Policy Process. (1st ), Westview Press Boulder, United States dos America p. 73-93.

- Mucciaroni G (1992) The Garbage Can and the Study of Policy making: a critique. Polity 24(3): 459-482.

- Albaladejo G (2014) Introducción al estudio teórico y práctico de las políticas pú In: Albaladejo G. (Ed.). Teoría y Práctica de las Políticas Públicas. (1st Ed.), Editora Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia, Spain p. 9-14.

- Bañón R, Carrillo E (1997). La Nueva Gestión Pú (1st Ed.), Alianza Editora, Madrid, Spain pp. 1-345.

- Alcázar M (2000). Curso de Ciencia de la Administració (4th Ed.), Tecnos, Madrid, Spain.