Multiculturalism and Bilingualism Policies in Canada through Immigrant Adaptation Lens

Makarova V*, Davoodizadeh F and Morozovskaia U

University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Submission: February 01, 2024; Published: February 15, 2024

*Corresponding author: Makarova V, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

How to cite this article: Makarova V*, Davoodizadeh F and Morozovskaia U. Multiculturalism and Bilingualism Policies in Canada through Immigrant Adaptation Lens. Acad J Politics and Public Admin. 2024; 1(2): 555556. DOI:10.19080/ACJPP.2024.01.555556.

Abstract

This article describes the multiculturalism and bilingualism policies in Canada and reports the results of a study that explores the level of adaptation of two groups of immigrants to life in Canada, perceived levels of discrimination as well as their satisfaction with the move to Canada. It also explores the perceived importance of home language and culture maintenance and of the majority language (English) acquisition by immigrants. The two immigrant groups selected for the study were Iranian and Russian speakers. This choice is motivated by the negative portrayal of their home countries in Canadian politics and media as well as by an insufficient number of studies of adaptation of these two groups in Canada. The results demonstrate that both groups are overall satisfied with their move to Canada, but their level of integration into the majority social groups is relatively low. Immigrants from Iran form close connections with their diaspora, whereas Russian speaking immigrants do not. Both groups of immigrants are determined to maintain their language and culture and pass them over to their children. Immigrants from both groups report incidents of discrimination, which are more frequent among Iranian participants. The discussion raises the current issues with bilingualism policy and makes suggestions for its substitution with multilingualism to facilitate a better adjustment of immigrants in the host society as well as to improve equity, diversity, and inclusion in Canada.

Keywords: Immigrant; Language ideologies; Ethnocentrism and discrimination; Multilingualism; Equity; Diversity; Inclusion

Introduction

This article attempts to unravel the functioning of multiculturalism and bilingualism language policy in Canada at the level of immigrant population that comes from two underprivileged immigrant groups. The study of adaptation experiences of the two immigrant groups is employed as a reference point for a debate of a conundrum of mismatched ‘multicultural’ and ‘bilingual’ policies in Canada. As a starting point, we introduce the definition of language ideologies and policies. Every modern nation state develops language ideologies and policies to regulate communication in society. “Language ideologies are morally and politically loaded representations of the structure and use of languages in a social world. They link language to identities, institutions, and values in all societies. Such ideologies actively mediate between and shape linguistic forms and social processes” (Woolard, 2020, p.1). Language ideologies are a powerful instrument of impact on society, since they “forge links between language and other social phenomena, from identities (ethnic, gender, racial, national, local, age-graded, subcultural), through conceptions of personhood, intelligence, aesthetics, and morality, to notions such as truth, universality, authenticity” (Woolard, 2020, p.1). They can also contribute to linguistic discrimination (linguicism) and language endangerment and death (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2000).

Examples of different language ideologies are monolingualism (only one language in the nation is promoted), bilingualism (the use of two languages is supported) and multilingualism. Multilingualism is an ideology which recognizes “the richness and complexity of linguistic diversity in a globalized world” (Heller, 2007). The linguistic diversity is widely acknowledged in Canada; it is very much a part of public debate and research discussions e.g., (e.g., Kymlicka, 2010). However, for an ideology to be brought to actual manifestation in society, it needs to be transferred into a policy. Language policies are established via legislation, and they can include court decisions, executive action, or other means (Linton,2006, p.1). p.1. They determine how languages are used in public, they cultivate and prioritize the command of languages needed in the nation, affirm and protect the rights of individuals or groups to learn, use, and maintain languages, as well as to establish “a government’s own language use” (Linton, 2006, p.1)

Literature review

While cultural and linguistic pluralism in Canada is often praised and promoted in research studies (e.g., Adams, 2007), there is a certain confusion among public on whether Canada is a bilingual or multilingual country, which results from an asymmetry of cultural and language policies. The official cultural policy is that of “multiculturalism”, which is somewhat controversial. Multiculturalism in practice existed in Canada since its foundation as a Confederation in 1867, which involved the British, the French and the Indigenous nations (Wong & Guo, 2015, p. 2). Immigrants and refugees of different races, ethnicities and home countries have been coming into the country before and since then. However, the official Multiculturalism policy was introduced in 1971 in response to public protests representation of only the French and the British in legislation. The identified purpose of the policy was to recognize different cultural groups, promote encounters and interchange between different groups, help them overcome barriers to full participation in society, and assist them in learning the official languages (Dewing, 2013). Multiculturalism policy was subsequently confirmed and institutionalized in the Constitution of 1983 and in Multiculturalism Act of 1988 (Wong & Guo, 2015, p. 2).

Since language is intrinsically connected with culture (Levi- Strauss, 1966), it may be logical to expect a multilingual policy that reflects the cultural policy. However, from the viewpoint of legislation, Canada is officially not multilingual, but bilingual at the federal government level. According to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Constitutional Act [7] section 16, “English and French are the official languages of Canada and of its Parliament.” There are multiple references to ‘minority languages’ in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and the protection of minority languages education (Section 23), but ‘minority languages’ refer only to English and French: “the English or French linguistic minority population of the province” (Section 23). The Charter also allows provincial governments to override the above language laws. In line with this clause, in 2022, Quebec revoked the rights of English speakers, rescinding government services in English and education in English (with some exceptions for people whose ancestors have been proven to pursue English medium education) and is officially now a monolingual French-speaking province. The legislation that introduced this change is known as “Bill 96” or “An Act respecting French, the official and common language of Québec.”

The only officially bilingual province is New Brunswick (where English and French have equal rights). Formally, one more bilingual province is Manitoba. While most of the population speak English there, one can get legal and other government service in French. Some regions in Ontario (but not the province on the whole) are bilingual as well. By contrast, truly multilingual are the country’s two territories: Northwest (Chipewyan, Cree, English, French, Gwich’in, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey, South Slavey, and Tłįchǫ or Dogrib) and Nunavut (English, Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun, and French). Yukon (the third Canadian territory) is officially bilingual in English and French. Thus, a stereotypical outsiders’ perception of Canada as a bilingual (English and French speaking) nation, which likely comes from bilingual announcements on Canadian aircrafts, is far from actuality. Canadians speak English or French, Indigenous languages as well as immigrant languages. In this article, we focus on the immigrant languages. Over 200 immigrant languages are spoken in Canada as mother tongues, with the top language by the number of native speakers being Mandarin (679,000 individuals), Punjabi (667,000 speakers), Yue or Cantonese (553,000), and Spanish (539,000) (Statistics Canada, 2021). In sum, in contrast to the bilingualism policy at the Federal level which is in opposition to multiculturalism, we observe monolingual, bilingual and multilingual policies and practice amongst Canadian provinces and territories.

Criticisms of Multiculturalism and Bilingualism policies

Multiculturalism has often been criticized for potentially defending behaviours non-compliant with the Canadian code of law, inequalities inherent to the hierarchy within immigrant communities, the use of religious legislative systems instead of Canadian legislation, etc. Another concern was for a symbolic nature of multiculturalism that did not translate into specific measures of a fuller inclusion of immigrants into the economic and social frameworks (e.g., Kymlicka, 2010, pp. 314-315). Official bilingualism policies in Canada have been even stronger criticized by academics and the public. In scholarly arguments, as summarized in Ricento (2013, p. 40), pointed out that “the framework of official bilingualism and multiculturalism is inadequate from a practical standpoint”, and is “at odds with Canada’s self-image as a ‘mosaic’ of cultures and languages”. It “tends to marginalize the status of ‘other’ groups and their languages within Canada, but it also presents an image of Canada, to itself and the world, that does not reflect the changing demographics and linguistic complexity of the country” (Ricento, 2013, p. 475). An example of the public concern is a letter published in Star Phoenix (Saskatoon newspaper) in 2023 in which the author points out that the policy reflects a narrow view of bilingualism. Many Canadians are bior multilingual in languages other than French, and the official bilingualism policies are jeopardizing their potential careers as they have “have created a language-based glass ceiling for many Canadians seeking federal level jobs.” (StarPhoenix, 2023). Another relatively recent online magazine entry discusses the decline in the numbers of English-French bilinguals, questions the necessity for a policy imposing the official bilingualism all over the grid, and puts forward some region-based reform suggestions (Polèse, 2022). Next, we consider how immigrants adapt to a new environment in the host country.

Immigrant adaptation

The traditional term for adjusting to the life in a host country is ‘acculturation’. Acculturation can be defined as “the process of cultural and psychological change, resulting from contact between groups and individuals of different cultural backgrounds” (Sam and Berry, 2016, p.11). Many different approaches to acculturation have been developed, and in some of them language plays a crucial role. For example, Schumann’s acculturation model (1978) focuses on the new language acquisition that is supposed to assist with social, cultural and psychological integration as well as with communicative competence. Communication Accommodation theory (CAT) looks at how individuals adjust their language and communication style when interacting with people from different cultural backgrounds. Language adaptation in CAT is seen as a strategy for achieving social harmony and reducing intergroup tensions during acculturation (Giles et al. (1991)). Critical Acculturation theory focuses on language use to resist or challenge dominant cultural norms and expectations during acculturation (Kanno, 2008). The tridimensional process-oriented acculturation model TDPOM (Wilczewska, 2023). understands culture as a process rather than a permanent state. It is centered not on the acquired similarities or dissimilarities with another group during acculturation, but on what people “do and how they respond to the situation of contact with a new culture in terms of practices” (Wilczewska, 2023, p.1) In this paper, we will follow the most widely known Berry’s (1997) Acculturation theory that largely ignores language and operates predominantly with cultural notions. However, even if criticized for its lack of dynamic features, Berry’s Acculturation theory is one of the most cited sources (Ahn & Lee, 2023). It offers major types of acculturation strategies that are very commonly used in research and are useful in terms of identifying some major pathways of acculturation (e.g., Giles et al. [19].

Berry’s (1997) model includes the following types of acculturation strategies.

i) Integration (otherwise known as biculturalism) refers to adopting the cultural patterns (and language) of the host country while retaining the home country’s ones. This strategy is highly recommended by researchers as the immigrants following this strategy tend to be better adjusted, for example they have a higher self-esteem, lower depression, etc. (e.g., David et al., 2009).

ii) Assimilation is the process of adopting the cultural patterns (and language) of the host country while rejecting the home country’s cultural norms.

iii) Separation is defined as a pattern of retaining one’s home country’s cultural norms (and language) while rejecting the host country’s ones.

iv) Marginalization is rejecting the home and the host cultures. It has no analogue in language strategy, as it is impossible not to use some language for communication.

In this paper, we employ the term “adaptation” instead of “acculturation”, since the latter term is disrespectful of immigrants. The term “adaptation” has also been used in previous research Sonn, 2002; Makarova & Morozovskaia, 2022. As we will show in the next section, languages are an important component of adaptation.

The role of languages in immigrant population

Both the host and home languages can be of high importance for immigrants. Acquiring the majority language of the country is necessary to get a job, pursue education, for daily functioning (shopping, banking, etc.) and interaction (Hill et al., 2021). On the other hand, home language and culture maintenance are important for identity reconstruction, heritage, recreation, ethnic festivals, and psychological balance (Berry and Hou, 2019; Nguyen, 2022). The language roles and their interactions with identity construction can be impacted by multiple factors, for example, by demographic factors, such as age or neighborhood. For example, English language use is related most positively to self-esteem in predominantly non-Chinese neighborhoods, and Chinese cultural participation is related positively to self-esteem only in predominantly Chinese neighborhoods (Schnittker, 2002). Thus, immigrants in the new host country, in particular, the ones following integration policy become bilingual in the home language (L1) and the language of the majority (L2). The majority language (L2) typically has a higher prestige and is widely spread, and provides advantage in social and economic terms, so it becomes employed by the immigrants in different spheres of their lives (De Mejía, 2002). By contrast, the home language (L1) has often low prestige in the context where the immigrant individuals live; hence, a likely consequence is subtractive monolingualism, i.e., many immigrants may gradually shift to the use of L2 only and experience some level of attrition of L1 (Gallo et al., 2021).

Bilingualism is “a complex linguistic and cognitive phenomenon that occurs when individuals acquire and use two languages in their everyday lives. This involves varying degrees of language dominance, interaction between the languages, and cultural integration” (Wei, 2018, p. 163). In this paper we adopt a Sociolinguistic perspective on bilingualism, which identifies bilingualism as a social phenomenon, which is impacted by linguistic and cultural interactions in multilingual societies. Bilingualism from the Sociolinguistic perspective is connected to ethnic, cultural and other components of identity, and individuals’ navigation of social dynamics Fishman (1991). Yet, following the governmental language policies, not all languages are equal, and the resources for language and culture support are often distributed depending on the perceived status of these languages. Romaine (1995) identified two kinds of bilingualism. The first of these is Elite bilingualism - a socially desirable bilingualism in the official/ national languages of the country. In Canada, this bilingualism in the the official English and French is highly coveted for any governmental job (Lynch, 2003). The second type of bilingualism is Folk bilingualism –which typically involves one language which is not official/national language of the country, i.e., a language which is not socially desirable to individuals outside the language speakers’ group. Russian and Farsi languages fall within the Folk bilingualism group in Canada. We will next describe these groups.

The immigrant groups in the study

Ethnic groups have been called “a major element in Canadian society” (Kymlicka, 2010, p. 304). First-generation immigrants currently comprise 26.4% of Canadian population Census Mapper (2022). Therefore, exploring immigrants’ adaptation to their new life in Canada is of crucial importance. Of all the immigrant groups, we selected two: Iranians and Russians. The reasons for this selection are based, first, on the fact that Canadian media portray the two countries of origin in a very negative light. Russia has been negatively portrayed even before the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war (Mastracci, 2023) and the coverage escalated to overt hatred and bashing after it (e.g., Russia’s Attack on Ukraine, 2022). It must be noted that the current study was conducted before the onset of the war. Similarly, Iran has a long history of being negatively portrayed in Canadian media (Jahedi et al., 2015). Thus, it is possible to expect more negative experiences with adaptation in these two groups. Second, research in the languages and cultures of these two groups in immigration are within the scope of expertise of the authors.

Iranian immigrants in Canada

There are currently about 210,620 first-generation immigrants from Iran residing in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2023). The increasing number of immigrants from Iran is explained by financial instability and violation of human rights in Iran (Bahri, 2023). Iranian immigrants are reported to be interested in maintaining their language and culture, but also often switch to English use (Babaee, 2014). Many Iranian immigrants are involved in ethnic festivals and have contacts with other Iranians Khaleghi, 2009).

Russian immigrants in Canada

The number of Russian immigrants in Canada in the past decades has been around half a million people with some considerable fluctuations in population. For example, in 2011, there were 550,520 people of Russian descent who moved to Canada (Statistics Canada, 2011), in 2016, the number increased to 622,445 (Statistics Canada, 2016), and decreased again to 548,140, according to the 2021 Census (Statistics Canada, 2022). The reasons for immigration have been economic and political; the Russian immigrants are known to be well-educated, older than other immigrant groups, mostly speak one of Canada’s official languages upon arrival and have high maintenance rates of the language (Hou & Yan, 2020; Makarova, 2020). The research gaps in the previous research suggested our focus in this paper on the goal of comparing adaptation-related experiences by Iranian and Russian immigrants. The research questions are:

i) Do Iranian and Russian immigrants feel that they fit well into Canadian society?

ii) Do they feel discriminated in Canada?

iii) Do they build connections with their immigrant diasporas or with other groups of residents?

iv) Do they feel the need to maintain their languages and cultures?

v) How can these immigrants’ experiences inform multiculturalism and bilingualism policies?

Materials and methods

An online questionnaire was developed and used to collect the data based on previous studies of immigrants’ adaptation and linguistic experience (Isurin, 2011; Makarova and Morozovskaia, 2022). The online questionnaire was published in Farsi and Russian languages on SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey. com), an online survey platform. The questionnaire consisted of four different parts: demographic, adaptation, and language use. The questions included Likert scale and open-ended questions. Participation in the questionnaire was anonymous and voluntary. Participants were recruited via the website of the home institution. The participation criteria were being an immigrant who has lived in Canada for at least three years, the mother tongue (Farsi or Russian), age of 18 years old or above. After completing collecting the data, they were extracted in Microsoft Excel Table form and analyzed using the Chi-square test (the significant level of p < .05) in SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 27).

Participants

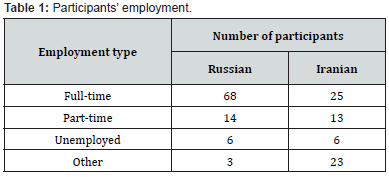

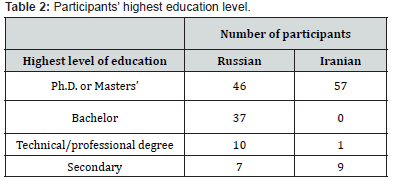

There were 100 Russian participants (80 female, 18 male, 1 ‘other gender’, 1 undisclosed gender). Their average age was 42,5 years. The participants lived in seven different provinces. A total of 67 participants constituted the Iranian sample (40 female, 27 male) with an average age of 34 years and representing 5 provinces in Canada. Participants’ employment is presented in Table 1, which shows that most participants in both groups were employed, and very few of them were unemployed. However, there is a significant difference in employment across the groups, with Russian participants having more full-time employment and Iranians engaged in ‘other’ occupations: X2 (1, N = 167) = 32,40, p < .00001). ‘Other’ category included full-time students who did not work, retirees and individuals with disabilities. Participants’ highest education level is presented in Table 2. Iranian participants have a higher level of education, and this difference is significant X2 (1, N = 167) = 38,1, p < .00001. The above two differences are not intrinsic to the population but relate to more reliance on snowballing among graduate students in Iranian participants’ recruitment.

Results

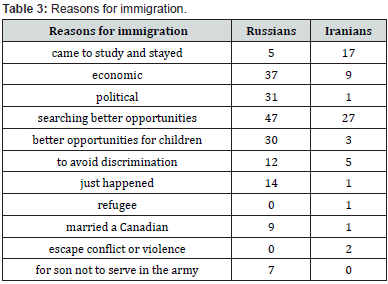

Reasons for immigrating: When asked a question “What were the reasons for your immigration to Canada”, the participants provided the answers summarized in Table 3. Both groups came to Canada primarily in searches of better opportunities. However, there were more Iranians than Russians who came to Canada to study and stayed. Economic reasons and seeking better opportunities for children were highly prominent for Russians. However, a chi-square test did not show significance of the differences: X2 (1, N = 167) = 0.72, p = .08.

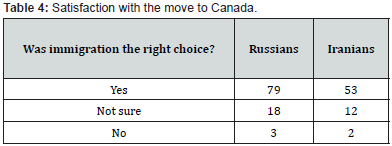

Satisfaction with the move to Canada: When asked whether the move to Canada was the right decision, the participants provided responses as represented in Table 4. As the table demonstrates, both groups consider immigrating to Canada to be the right choice, and there is no significant difference between the groups as shown by a chi-square test: X2 (1, N=167) = 0.0003, p = .99.

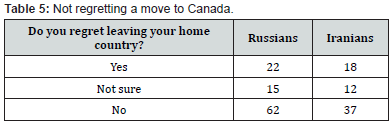

Regretting leaving the home country: When asked whether the participants regretted leaving their home country, the majority in both groups responded that they did not, as shown in Table 5, and there is no significant difference between the groups’ response: X2 (1, N=167) = 0.91, p = .63.

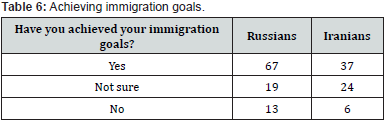

Achieving immigration goals: The next question asked participants whether they had achieved their goals in immigration. The responses are summarized in Table 6, which suggests that both groups mostly achieved their goals in immigration, and there is no significant differences in responses across the groups: X2 (1, N=167) = 5.86, p = .053.

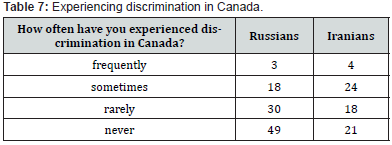

Discrimination: When asked, “How often have you experienced discrimination in Canada?”, the participants produced responses summarized in Table 7. As the table shows, about a half of Russian participants and 69% of Iranians have experienced discrimination in Canada, whereby Iranians face discrimination significantly more than Russians (X2 (1, N = 167) = 9.03, p = .028). This could be attributed to more discrimination directed at a visible minority.

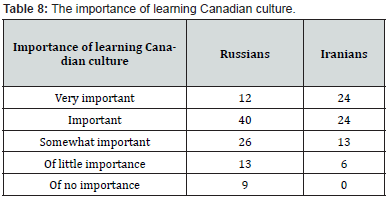

Importance of learning Canadian culture: The participants indicated how important learning Canadian culture was for them, as presented in Table 8. They answered the question “How important for you is learning Canadian culture?” As the table indicates, learning Canadian culture was of some degree of importance for both groups, but Iranians allocated more importance to learning Canadian culture (X2 (1, N=167) = 16.40, p = .002).

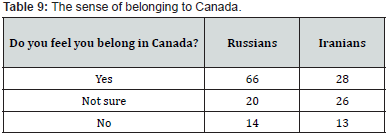

The sense of belonging in Canada: In their answers to a question “Do you feel you belong in Canada?”, both immigrant groups responded for most part positively, although there were many ‘not sure’ responses (Table 9). There is a significant difference between the responses by Iranian and Russian participants ((X2 (1, N=167) = 10.05, p = .006). Iranians feel less sense of belonging to Canada than Russians.

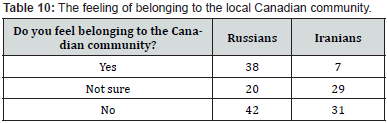

The feeling of belonging to the local Canadian community: Table 10 summarized responses to the question “Do you feel that you belong to the local Canadian community?” As the Table 3 shows, the participants do not feel they belong to the local Canadian community, and Iranian participants feel less sense of belonging than the Russian peers (X2 (1, N=167) = 18.8, p = .00007).

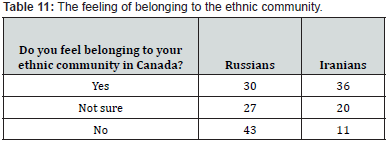

The feeling of belonging to the ethnic community: A question “Do you feel belonging to the ethnic (Iranian or Russian) community in Canada” split the opinions by groups again. Most Iranians thought that they belonged to the Iranian community, whereas most Russians believed they did not belong to the Russian community (Ref Table 11). This difference is significant (X2 (1, N=167) = 14.6, p = .0006).

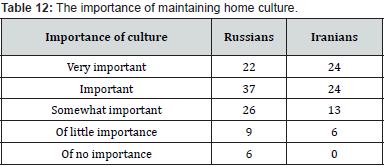

Maintaining home culture: The participants’ responses to the question “How important is it for you to maintain your home language?” are represented in Table 12. As can be seen from Table 12, most participants consider home culture maintenance very important or highly important. There is no significant difference between the responses of the groups (X2 (1, N=167) = 5.6, p = .23).

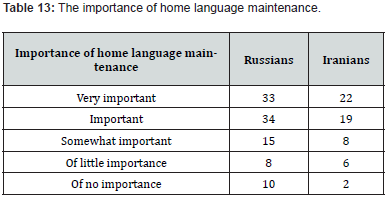

Maintaining home language: Table 13 reflects the participants’ answers to the question “How important is home language maintenance for you ?” According to chi-square test, there is no difference between the two groups’ opinions (X2 (1, N=167) = 2.6, p = .62).

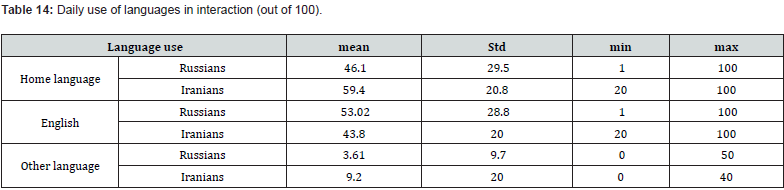

Languages of communication across the groups: Another question related to language use that we asked the participants was “What is the amount of your daily interactions in Farsi, English, and other languages now? (In percentage 0-100%)”. ANOVAs (single factor) were conducted for each language use by the two groups. The difference in the reported amount of use of the home language between Russian and Farsi speakers is significantly different [F (1, 165) = 10.1, p = .001], whereby Iranians speak more home language. There is also a significant difference in the amount of English use across the groups with Russians using more English daily [F (1, 165) = 5.06, p = .02]. By contrast, Iranians speak more in ‘other’ languages [F (1, 165) = 7.69, p = .006]. Russian participants speaking more English, and less home language as compared to Iranian immigrants could probably be explained by a higher ratio of employed individuals in the Russian sample. An important outcome is that both groups report speaking about ½ in English and ½ in their home language in daily interactions in Canada.

Importance of passing over home language and culture to children

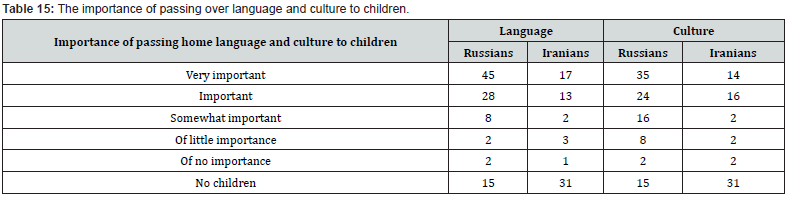

To address the participants’ will of passing their heritage to their children, we asked them two questions: “How important is it for you to pass over your language to your children?” and “How important is it for you to pass over your culture to your children?” Table 15 contains the responses to these questions by participants. Passing on home language and culture to children is important or very important to both participant groups. There is no significant difference between the two groups of participants in their desire to pass over either home language (X2(1, 121) = 2.89, p = .57) or home culture (X2(1, 121) = 6.27, p = .17) to their children. No significant differences exist between the perceived importance of passing language and culture either for Russian immigrants (X2(1, 85) = 7.82, p = .09) or for Iranian ones (X2(1, 36) = 1.13, p = .88). In other words, teaching both home languages and cultures to children are highly and equally important for both participant groups.

Suggestions for changes in languages and cultures policies and practice expressed in open-ended responses.

Many participants in both groups commented that nothing needed to be changed, as Canada is already very friendly to immigrants. While many suggestions were made about improving immigration and visa processes, healthcare, as well as job market access for newcomers, we will only report here the participants’ wishes that relate to language and culture. Russian participants called for more Russian schools and language programs for children (3 participants). They also would prefer having more cultural activities, such as concerts, clubs, conferences about Russian speaking immigrants in cultural centers and universities (3). One participant added that acquainting Canadians with Russian culture could ameliorate negative attitudes. Two participants commented on ethnocentrism and discrimination: “It would be good if your ethnicity did not impact how people are talking with you, because sometimes you are perceived as a person of a lower class, if you are not Canadian. It would be also great not to have ethnicities that are more ‘favoured in Canada’”. One more person added that the negative politics directed to Russia impact the attitude to immigrants from Russia. Another participant voiced similar concerns: “It would be great if mass media stopped portraying Russia as a terrible country. But in communication with individuals, I never notice hostilities just because I am from Russia.”

Differences in cultures were mentioned as well. As summarized by one participant, “Canadians don’t know Russian culture and judge us wrong. We don’t smile as much because we value honesty not because we are mean. When I was growing up being shy and modest was a virtue, but not in a Canadian society. I had to learn to praise myself and my skills. Movies always portray Russians as bad guys too. Some people might take it literally. In Russia, when people ask how you are, they really want to know, here the first I had to learn always to answer I am fine even if my place is flooded and don’t tell people how you really are. Since Canada is a multicultural country, I personally believe in school some kind of diversity course should be part of graduation requirement.” By contrast, for Iranian participants, the top priority was increasing the presence of Iranian culture (5), for example “include Farsi in the urban elements of the city” (1), “having more events in Persian” (1), “to care more about Iranian culture and celebrations” (1), and “promote Iranian culture” (2). An availability of free English language classes came as the next top priority mentioned by four individuals.

Another suggested improvement was changing negative attitudes towards Iran and Iranians (3), such as “lifting developing country attitudes towards Iranian immigrants” and “changing Canadian’s thought toward Middle Eastern countries and avoiding racist attitude”, stopping discrimination and encouraging cross-cultural dialogue: “Canada could take steps to combat discrimination against immigrants including Iranians by increasing awareness and education on cultural diversity and encouraging cross-cultural dialogue and understanding”. There was one suggestion to “remove French language in Western Canada”. In sum, the open-ended responses data are indicative of a high level of satisfaction of the participants with life in Canada and with multicultural milieux. However, some improvements are suggested by both groups that relate to a better availability of ethnic events, eliminating discrimination and negative attitudes. For the Russian immigrants, bilingual schools for children are important as well, as the Russian participants were older and had more children than the Iranian group.

Discussion

Multiculturalism policy in Canada is, certainly, an outcome of social progress, as it “specifically recognizes the importance of preserving and enhancing the multicultural heritage of Canadians” and acknowledges the rights of Aboriginal people (Canadian Multiculturalism Act, 1988, p. 31). It further states that “English and French are the official languages of Canada”, but this fact “neither abrogates nor derogates from any rights or privileges acquired or enjoyed with respect to any other language”. Most importantly, it states the aim “to facilitate the acquisition, retention and use of all languages that contribute to the multicultural heritage of Canada.” This statement is highly supportive of all languages of Canada. However, in practice, education in Canada is delegated to provinces, and they struggle with providing much in terms of support of immigrant languages maintenance and teaching. The amount of support strongly differs by province and location (Makarova, 2020). For example, Edmonton (Alberta) has about 13 bilingual Mandarin-English schools, and Saskatchewan has none (Makarova and Xiang, 2022). Ethnic festivals and other events are largely left for the communities to organize and sponsor (Zubyk and Lozynskyy, 2017). As pointed out in earlier research, Canada needs “to live up to its official status as a multicultural country” (Takševa, 2024). The sense of belonging to Canada has been earlier reported to differ by the province of residence, and it is higher in Ontario and Atlantic Provinces than in British Columbia and Alberta (Stick et al., 2023). Our study shows a relatively high sense of belonging to Canada, but low sense of belonging to the social group of Canadians, especially among Iranians. It also shows differences in the patterns of belonging by immigrant groups.

The factor of discrimination comes up in both groups’ responses. This is not surprising, as multiple studies of discrimination of immigrants in health care access, employment and other areas are well protocolled (Edge & Newbold, 2012; Fang & Goldner, 2011; Nangia, 2013). What needs to be noted in the context of discrimination is the concept of a ‘linguistic minority’. According to Canadian government definitions, linguistic minorities are not included amongst “equity, diversity, and inclusion” groups (EDI). However, it is difficult for immigrants who are not native speakers of English to get jobs, succeed in academic studies, etc., which makes them a clearly a vulnerable group, no matter what race or ethnicity. Linguicism or “linguistic racism,” discrimination of people based on their language, dialect, or language-related characteristics (Dovchin, 2019, p. 334) needs to be identified as one of the forms of discrimination, and respectively, immigrants who are non-native speakers of English need an acknowledgement as an EDI (equity, diversity, inclusion) group in Canada. The value of their home languages and cultures and the desire to maintain them become loud and clear in the participants’ interview responses. These results indicate that there is a need for the government to supplement a ‘declaration’ of multiculturalism with specific programs and financing of multicultural events in conjunction with local communities. Even more importantly, it may be time to step aside from the much criticized ‘bilingualism’ policy towards ‘multilingualism’ policy that reflects the aspirations of immigrants who constitute one quarter of Canada’s population.

Conclusion

Our investigation of adaptation and language use by Iranian and Russian immigrants in Canada showed that both groups have similar reasons for immigration that reflect overall migration trends (e.g., Asayesh & Kazemipur, 2024). Both groups have quite similar experiences in Canada, largely successful ones, even if not entirely devoid of discrimination, which is likely explained by lack of knowledge of the two cultures by most other Canadian groups as well as the negative impact of government and mass media propaganda against the two countries of origin. The impact of negative coverage on immigrants’ adaptation and identity still needs to be ascertained in future studies. Immigrants from Iran and Russia are for most part satisfied with their move to Canada and consider their goal of immigration to Canada achieved. However, about one fifth to one quarter of them regret leaving their home country, which might be due to nostalgia or other considerations that are yet to be determined in future research. Both groups have faced discrimination in Canada, and it is stronger in the Iranian group’s case, which may be determined by visible minority characteristics or other factors (that remain to be determined).

Probably connected to the above discrimination experiences, as compared to ethnic Iranians, there are more Russian respondents who feel that they belong in Canada, are adapted to the country, and feel that they fit in Canadian community. It should be noted that in both groups, there are more individuals who report not belonging to Canadian community that those who do. Iranians feel a stronger sense of belonging to their ethnic immigrant community than Russians. For both groups importance of home language and culture maintenance is highly important along with learning English and Canadian culture. Both groups use the home language and English in their daily communication, but Iranians use more home language than the Russians do (which is probably explained by the difference in the samples with more Russians being employed and having to use English at work). Passing over the home language and culture to children is also important in both groups.

Some outcomes of international significance of this paper relate to first, our suggested substitute of the term “acculturation” with “adaptation”, since the latter sounds more neutral and respectful of immigrant population. Second, researchers need to bring forward to local governments, university administration and other stakeholders an understanding of unacceptability of linguicism, which should be on the same ‘chopping board’ as racism. Equity, diversity and inclusion categories need to be broadened up to include linguistic minorities.

As far as the local situation in Canada is concerned, it is time for the country to develop language legislation that addresses languages other than English and French. There is a fundamental logical discrepancy (or dissymmetry) between multiculturalism and bilingualism policy on the one hand and between multilingual landscape of the country and bilingualism legislation. Canada has the potential of becoming a truly multilingual and multicultural nation where any kind of bi-multilingualism is valued and appreciated. No matter what language a person may speak, they can contribute to the country’s future and receive equitable rights to occupy governmental and other positions. With Quebec abolishing English language rights, there are hardly any reasons for Federal government and especially for Western Canada (with very small Francophone populations) to unilaterally maintain French language rights and spend enormous amount of money on French education and leave all other languages behind.

References

- Woolard KA (2020) Language ideology. In: The International Encyclopedia of Linguistic Anthropology, John Wiley & Sons.

- Skutnabb-Kangas T (2000) Linguistic Genocide in Education-Or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Routledge.

- Kymlicka W (2010) Ethnic, linguistic and multicultural diversity of Canada. In: JC Cortney and DE Smith (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, England pp. 301-320.

- Linton A (2006) Language politics and policy in the United States: Implications for the immigration debate, CCIS pp. 141.

- Dewing M (2009) Canadian Multiculturalism. Library of Parliament, Ottawa, Canada.

- Lévi-Strauss C (1966) The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Chicago, US.

- Constitutional Act (1982) Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Section p. 16.

- Statistics Canada (2021) Language Diversity Statistics in Canada.

- Ricento T (2013) The consequences of official bilingualism on the status and perception of non-official languages in Canada. J Multilingual Multicultural Dev 34(5): 475-489.

- StarPhoenix (2023) Federal language policy discriminates against Saskatchewan.

- Polèse M (2022) Is bilingualism doomed? Policy Options.

- Sam DL, Berry JW (2016) Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (2nd ). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Schumann JH (1978) The acculturation model for second language acquisition. In N Doughty & R Long (Eds.), Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, Wiley p. 27-50.

- Giles H, Coupland N, Coupland J (1991) Accommodation theory: Communication, context, and consequence. In H Giles, J Coupland, & N Coupland (Eds.), Contexts of accommodation: Developments in applied sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press, England p. 1-68.

- Kanno Y (2008) Language, identity, and stereotype among Southeast Asian American youth: The other Asian. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Wilczewska IT (2023) Breaking the chains of two dimensions: The tridimensional process-oriented acculturation model TDPOM. Int J Intercultural Relations 95: 101810.

- Berry J (1997) Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, An International Review 46: 5-34.

- Ahn S, Lee S (2023) Bridging the gap between theory and applied research in acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 95: 101812.

- Giles H, Edwards AL, Walther JB (2023) Communication accommodation theory: Past accomplishments, current trends, and future prospects. Lang Sci 99: 101571.

- David EJR, Okazaki S, Saw A (2009) Bicultural self-efficacy among college students: Initial scale development and mental health correlates. J Counseling Psychology 56(2): 211-226.

- Sonn CC (2002) Immigrant adaptation: Understanding the process through sense of community. In Fisher AT, Sonn CC, & Bishop BJ (Eds.), Psychological sense of community: Research, applications, and implications Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, pp. 205-222.

- Makarova V, Xiang Q (2022) Mother tongue to heritage language metamorphosis: the case of Mandarin Chinese in Canada. Global Chinese 8(2): 189-209.

- Berry JW, Hou F (2019) Multiple belongings and psychological well-being among immigrants and the second generation in Canada. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement 51(3): 159-170.

- Nguyen XL (2022) Maintaining Cultural Values, Identity, and Home Language in Vietnamese Immigrant Families: Practices and Challenges. PhD Thesis, University of Windsor. Electronic Theses and Dissertations pp. 8980.

- Schnittker J (2002) Acculturation in Context: The Self-Esteem of Chinese Immigrants. Social Psychology Quarterly 65(1): 56-76.

- De Mejía AM (2002) Power, Prestige and Bilingualism: International Perspectives on Elite Bilingual Education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Gallo F, Bermudez-Margaretto B, Shtyrov Y, Abutalebi J, Kreiner H, et al. (2021). First language attrition: what it is, what it isn’t, and what it can be. Front Human Neurosci 15: 686388.

- Wei L (2018) Bilingualism and Multilingualism. In: Wei L, Hua Z and Simpson J (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Applied Linguistics. Routledge pp. 162-177.

- Fishman JA (1991) Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Multilingual Matters.

- Romaine S (1995) Bilingualism. Oxford: Blackwell, US.

- Census Mapper (2022).

- Mastracci D (2023) The ‘Disinformation’ craze is ruining what’s left of journalism. The Maple.

- Russia’s attack on Ukraine parks outrage in Canada’s multilingual media (2022) New Canadian Media, Canada.

- Jahedi M, Abdullah FS, Mukundan J (2014) Review of Studies on Media Portrayal of Islam, Muslims and Iran. Int J Education Res 2(12): 297-308.

- Bahri SA (2023) Creating a Sense of Place for Iranian Immigrants in Canada. MA Thesis, University of Alberta, Canada.

- Babaee N (2014) Heritage Language Maintenance and Loss in an Iranian Community in Canada: Success and Challenges. A PhD thesis. University of Manitoba, Western Canada.

- Khaleghi N (2011) Identifying Barriers to Iranian-Canadian Community Engagement and Capacity Building. MA Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Canada.

- Hou F, Yan X (2020) Immigrants from Post-Soviet States: Socioeconomic Characteristics and Integration Outcomes in Canada. In: Denisenko M, Strozza S, Light M (eds) Migration from the Newly Independent States. Societies and Political Orders in Transition. Springer, Cham pp. 373-391.

- Makarova V (2020) The Russian Language in Canada. In: Mustajoku A, Protassova E and Yelenevskaya M (Eds.). The Soft Power of the Russian Language: Pluricentricity, Politics and Policies, London/New York pp. 183-199.

- Isurin L (2011) Russian Diaspora: Culture, Identity and Language Change. De Gruyter, New York.

- Canadian Multiculturalism Act (1988).

- Zubyk A, Lozynskyy R (2017) Українські фестивалі Канади [Ukrainian festivals in Canada]. Rozvytok Ukrainskoho Etnoturyzmu: Problemy ta Perspektyvy, Lviv, Ukraine.

- Takševa T (2024) What it takes to feel Canadian: Multiculturalism and the logic of home. Canadian Ethic Studies 56(1): 55-81.

- Stick M, Scimmele C, Karpinski M, Cissokho S (2023) Immigrants’ sense of belonging to Canada by province of residence. Economic and Social Reports, Statistics Canada.

- Edge S, Newbold B (2013) Discrimination and the health of immigrants and refugees: Exploring Canada’s evidence base and directions for future research in newcomer receiving countries. J Immigrant Minority Health 15: 141-148.

- Fang ML, Goldner EM (2011) Transitioning into the Canadian workplace: Challenges of immigrants and its effect on mental health, Canadian J Humanit Soc Sci 2(1): 93-102.

- Nangia P (2013) Discrimination experienced by landed immigrants in Canada. RCIS Working Paper 7: 1-15.

- Asayesh O, Kazemipur A (2024) Culture of migration: A theoretical account with a practical focus on Iran. Canadian Ethic Studies 56(1): 1-26.

- Makarova V, Morozovskaia U (2023) The linguistic Odyssey of Russian-speaking immigrants in Canada. International J Bilingualism 27(6): 885-907.