Development Disparity & Attainment Discrepancy: A Return Migration Context

Pushkar. P. Jha

Faculty of Business and Law, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Submission: December 28, 2023; Published: January 09, 2024

*Corresponding author: Pushkar. P. Jha , Faculty of Business and Law, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

How to cite this article: Pushkar. P. Jha. Development Disparity & Attainment Discrepancy: A Return Migration Context. Acad J Politics and Public Admin. 2024; 1(1): 555552. DOI:10.19080/ACJPP.2024.01.555552.

Abstract

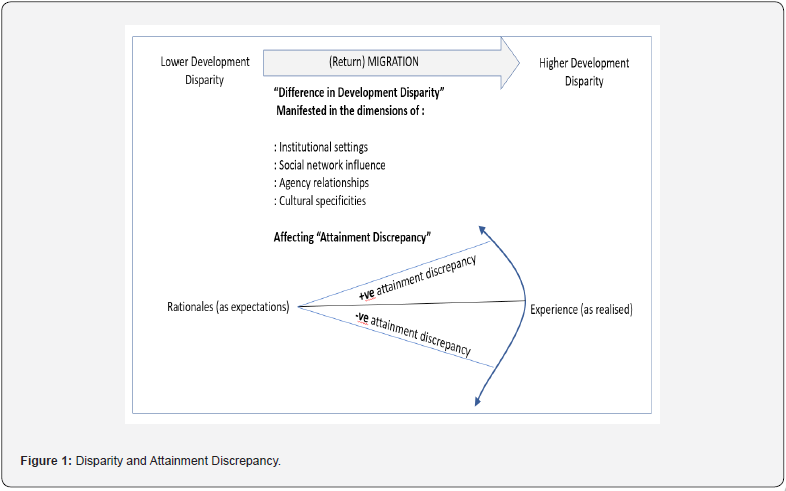

This paper discusses return migration rationales, realised experiences and any attainment discrepancy thereof. Attainment discrepancy is posited to be influenced by ‘difference in development disparity’. This is the ‘difference’ between inequality terrains that mark different countries. A structural functionalism platform is emphasised for how attainment discrepancy manifests - bringing society, institutions, agency, and culture in an interdependent - relational interface. Findings are presented for different domains where migrants’ rationales are discussed alongside associated experiences. Attainment discrepancy that arises due to ‘difference’ in development disparity is noted for: premium required to exploit a wider choice spectrum; evaluation of preferences; role of networks and influence of assurance mechanisms. The paper adopts the lens of return migration from developed country landscapes to a developing country. It seeks to open this perspective in research for future contributions to examine the interface between attainment discrepancy and difference in development disparity.

Keywords: Difference in development disparity, rationales, experience, attainment discrepancy

Introduction

Development disparity, as a variation in development levels in the population finds resonance with the much-discussed ideas of inequitable development; differences in ability and opportunity spaces and the construction of relative deprivation and relative affluence Banerjee & Puri [1]. Such disparity creates variation in offerings, choices, and access to them in the socio-economic space.

Aggregate development metrics do not provide a full picture of the development terrain in a country. However, the recognition of variation for understanding the extent of inequality has become quite pronounced. For instance, the use of Ginni coefficient to capture inequality is one popular trajectory to focus on disparity within a terrain categorised by aggregate measures Robert & Rao [2]. Amartya Sen’s [3] expression of development ‘as freedom to do and freedom to be’ and the idea of capabilities as opportunities to pursue well-being have influenced the development and uptake of the inequality ‘adjusted’ Human Development Index (IHDI), discounting average measures with distribution measures across the population Foster [4]; Hicks [5]. A correlation between conventional HDI and adjusted IHDI of the top 50 countries by HDI rank order is 0.91; the next 50 in the midriff demarcated broadly with a classification of developing countries shows a correlation of 0.64; the last 50 countries towards less /least developed status have a correlation of 0.94 (HDI.UNDP.org). These simple and statistically significant correlations provide a bolt on interpretation to reflect upon disparity in differences across countries. This has strangely enough, managed to escape scholarly interpretation. They suggest that superior infrastructure, services, robust institutional set up including better health and education guarantees –make for relatively less inequality in developed countries as a block (i.e. higher IHDI and HDI correlations) relative to developing countries. For less to least developed countries there is less to distribute, very low levels of opportunity spaces to strive for, making HDI and IHDI correlations strong, of course with values for each being consistently around a lower median in the full spectrum of countries.

In developing countries, it seems that the inequality premise is relatively stronger with a lower correlation between HDI and IHDI, there seems to be a skew which causes available opportunity spaces to be harnessed disproportionality. The issue for developing countries being less of availability and more of access to opportunity spaces and resources. Inequality implies that the development terrain is likely to be marked by greater troughs and peaks (in terms of relative deprivation and affluence). This would have a range of implications for cross border movement from the perspective of migrants. If the terrain is smoother in the ‘returned from’ country, this is likely to impart more need for adapting to new settings. Some changes and associated adaptations could be aspired for while others may require coping with. The paper examines the influence of ‘difference in development disparity’ on migrant ‘rationales’ and ‘experience’ of migration, and any attainment discrepancy (positive or negative) as a consequence. The chosen context is return migration from developed to a developing country terrain. Policy strategists may find implications of interfacing difference in development disparity with attainment discrepancy (discrepancy between migrant rationales and experiences) useful to inform policy calibrations for affecting return migration. Migrant decision-making frames are likely to benefit as well from such a reflection and from the conjectures that are drawn.

Extant research & conceptual moorings

Return Migration & Policy

Migration is a much written about phenomenon, arguably more so since the days of the empires with movement and sporadic settlement of military and administrative personnel, to slave trade, and migration induced by extension of trading interests. Typologies for capturing the nature of migration have also been numerous: temporary and permanent migration to begin with, and then, among others, a further classification that deals with the origin point, giving rise to what is labelled as return migration. In case of return from overseas, this is realized by coming back to the country of origin post international or more extended transnational outbound migration. The idea probably first caught the attention of scholars in mainstream economics when mass migration back from the United States to Europe in the nineteenth century indicated significant economic consequences. To a lesser extent, social and cultural consequences were noted, and other important punctuations have also been examined by scholars from a point of view of how return migration and affecting factors have changed over time Gould [6]; Dustman [7]; Dahles [8]; Bilgili [9]. Overall, there are three broad remits that such research is concerned with- explanations for return migration, shaping and sensemaking of policy impetuses and inevitably, but to a lesser extent, evaluation and analysis of return migration decisions.

Policy strategies for return migrants are very visible across countries, for instance, mobility arrangements; leveraging the emotional quotient by working on the feeling of belongingness and return to roots, through initiatives like -provision of overseas citizenship for people of origin; creation of non-resident quotas in higher education and flexibility and increased allowances in financial transactions, among others Lowell & Findlay [10]. This has typically been for motivating return migration - often subject to considerable planning and contemplation by potential returnees. Such interests of configuring a beneficial fit between return migrants’ interests and policy objectives, span several national and regional contexts across the globe. While the above specific policy impetuses are noted from an Indian context, the European Union also has an elaborate arrangement to support, encourage, monitor and council return migrants. This is with a stated intention of symbiotically imbedding return migrants in their home countries Kahanec [11]. Further examples would include countries like Malaysia with a state led ‘talent-return migration’ initiative that focuses on capabilities to fill gaps in the national economy to improve growth Koh [12]. The link between return migration and national growth continues to be at the forefront of research seeking to link development with migration. For instance, strategies have been drawn from research to inform policy makers in Ghana for drawing value from international ties return migrants have Setrana & Tonah [13]. Implications have also been drawn for developed countries like France from a perspective of how return migration intentions and behaviours could influence financial flows Wolff [14]. The reading of such research, and its uptake, clearly indicates that that the nature of policy input and interest across countries are deliberated based on how policy makers see development and growth to be affected by return migration.

Perspectives & Dimensions

The overall theorisation in migration studies, is a space shared by neo-classical economics, labour economics, structural constraints’ view and trans-nationalism. These are noted as perspectives. Broadly speaking, the neo-classical economics lens easily dominates research till date. This along with the structural perspective - relates realities of the country of origin with aspirations of migrants, and both together are argued to be the enveloping perspectives Cerase [15]; Brettell & Hollifield [16]. The trans-nationalism view bolts on with some distinction to speak of connections that a migrant has, both overseas (often multiple countries), and in country of origin giving a unique resourcing, networking and policy context embodied in the activity and identity sphere of the migrant.

There is an attempt to link perspectives more robustly through a spin-off into what may be labelled as dimensions. These comprise institutional settings, agency, culture, and social networks, with a more generous interface between them and therefore, not as discretely positioned as perspectives Drori, Hong & Wright [17]; Al- Ali & Koser [18]. For instance, the institutional dimension is argued as relatedness and adaptation with informal and formal institutional schemas is not only about access to resources, but to also deals with adaptation, considering expectations and differences when the migrants embody a shared frame between multiple institutional contexts. Delivering to aspirations and interests of migrants’ manifest across agency, social-network and cultural dimensions. These become a resource to leverage in some contexts, and an adaptation issue in others. Dominance of economic or occupational rationales by themselves have often been argued to be inadequate as explanations in research Gmelch [19]; Kingsbury & Scanzoni [20]; Hamdouch & Wahba [21]. The interaction between the dimensions finds moorings in structural functionalism, that brings society, institutions, agency, and culture in an interdependent - relational interface going beyond the structural view. To reiterate, while the conceptualisation of perspectives and dimensions overlaps, the latter are emphasised in a more interconnected way relative to the former. As discussed in the next section, this is a direction that research seems to be converging towards- arguably, for a greater congruence with policy and practice.

Onward from Economic & Structural Debates

Development status of countries and its interface with return migration has been discussed to suggest that typically, such migration is seen to contribute to economic development Kubat [22]. From a neoclassical perspective return migration also has a negative performance connotation – that of migrants not achieving their aspirations of economic gains, at least in relation to the work effort they make when overseas, and thereby returning to the country of origin Constant & Massey [23]; Stark [24]; Stark & Galor [25]. As outlined, there is a broader spectrum of meanings that can be called in for explaining return migration. Crease’s [15] work has been seminal in such an extension of meanings and has gathered substantial momentum over the last two decades, particularly from a success and failure point of view, and analysing pre-hoc and post-hoc contextualisation of experiences Dustman [26]. Studies following this trajectory have used panel investigation or secondary data where one strand continues to focus more on economics of return migration Cassrino [27]; Bijward [28]; Wahaba & Zenou [29]. The other strand however extends structural aspects with good rigour. For instance, Kirdar [30] examines annual surveys of socio-economic panels - to draw out interacting factors that need to be examined for their influence on return migration. Such studies extend and contribute to empirical evidence that has been growing over the last decade and a half, focusing on rationales behind return migration and exploring issues that dwell into sensemaking and evaluation of these by return migrants. These range from purchasing power parity, education, age and life-point based rationales to belongingness concerns, among others. The attempt is to seek an overall profile congruence for a fit that is considered attractive and thereby delivers better potential to induce successful return migration Bree [31]; Constant & Massey [23]. Lifestyle aspects have been put under focus as well, and with a highlight on motivations like better affordability for superior lifestyle Handlos [32]. The factors articulated above remain intertwined despite objective simplification- for example, purchasing power will interface with domains such as education, and belongingness bringing into context, the nature of institutional and social settings. Clearly the assessment of success will rely on initially set aspirations with any deviations manifesting as attainment discrepancy.

Data & Method

The qualitative data for this study is intended to draw inferences based on what underpins a variation between rationales and realised experiences across a range of categories return migrants reflect upon in making decisions. Studies deploying the Gallup World Poll that call upon the idea of subjective well-being to understand migration intention have provided interesting perspectives and a validation for such lumping and aggregation. For instance, Cai, Esipova Oppenheimer and Feng [33] provide evidence that objective measures explain less of intentions than constructs like ‘well-being’. The reason they give is not about it being a different measure but a more inclusive measure that draws on intertwined factors. Further ahead lie even more cognitive and psychological constructs like happiness that draw on family, social, network, belonging in an interfacing manner Blanchflower & Oswald [34]; Bartram [35], and how kinship processes intersect with mobility aspects for racial formations Leinaweaver [36]. These again emphasise inadequacy of the idea of micro level factors adding up to yield an understanding of return migration and show favour for more integrative constructs.

Data based on qualitative narratives from 21 return migrants has been used to capture initial rationales and realised experience of outcome from return migration. The sample comprises return migrants of Indian origin from North America (United States 7; Canada: 3) and from Europe (UK: 9; Germany: 2), each from a different family unit. All the return migrants had been in India for between one year to two and a half years at the time of generating these narratives through in-depth interviews. Usually, a control group approach would be considered better for data collection at pre-and post-return migration points. However, limitations in nature of access bring forth a setting where data was collected only post return migration. This creates an upfront bias as experiences after return may cloud rationales for migration that existed before. To partially control for this, respondents were asked to first provide a description of what their experiences of return migration were, and then, as a second item, elaborate on what their initial rationales were. The approach was adopted based on a discussion on responses with a pre-test sample of four respondents, outside the twenty-one respondents in the main sample (two asked to narrate experiences first and two asked to articulate rationales first and then their experience). The discussion with these pre-tests set of respondents after interviews suggested that asking to articulate experiences before initial reasons for return migration yielded lesser bias.

Narratives generated were rather personalized, expressed by one of the adult migrant family members, as to whoever volunteered to do so (in 13 cases this comprised women respondents and the remaining 8 were men respondents). 2 return migrants had spouses who were not of Indian origin. In these cases, only the partner of Indian origin was requested for responses.

After a read through of the narratives, categories were derived for what comprised experiences after return and for what the rationales were. Two independent assessors (both doctoral students in strategy and decision-making domains) without any prior exposure to the study design kindly agreed to help for assuring reliability for such bracketing by looking at a sample of four respondents each. In part, they agreed with the categorisation but thought that the spread could be reduced. After a discussion, based on their reading and discussions thereon, initial seven categorisations/ domains for responses were compressed to four. This is given how discretely and substantively they were expressed: education, financial and asset management, domestic services, housing and lifestyle.

There are limitations in how the data is worked forward. This is because integrating profile information more strongly than contextualised in the findings (particularly age, profession, and income levels) made for inconclusive outcomes given the stratification it yielded in a limited sample. Age in the sample ranged from thirty-six to fifty-three years. Income levels in the returned from country, or in the home country- were not shared by nearly half the respondents. 18 families in the sample had the lead earner as a salaried employee – 5 with public sector and thirteen with private sector in the ‘returned from’ country. Of the remaining, 2 comprised self-employed professional and 1 small business owner- when overseas. The employment/ occupation profile changed somewhat on return, with 15 in the salaried category being in private sector jobs, while 3 working as self-employed professionals in the home country and the small business owner when overseas, not being in work in the home country arguing quasi-retirement and prospecting getting into a rental enterprise business at the time of the interview.

Observations: Attainment discrepancy between rationales & experiences

Education

This category is framed primarily with reference to school education as was dominant in the sampled families. 14 families had children of school going age and 3 migrant families had grown up children either in jobs in the host country or in Higher Education overseas. Of the remaining, 2 had younger children outside the school going age and 2 did not have children. A range of what comprised rationales for return and experiences in the aftermath are noted below. Relative affordability of private schools is one appreciated factor (as a rationale) but is negatively impacted by professionalism of schoolteachers being perceived to be lower in the country of origin (experience) than what was in the host country (9 respondents). Variation in institutional robustness or sufficiency comes to the fore here, private schooling is in high supply in India and quite varied in credentials, a good range of schools distinguished by fee levels can be found. This spread may be a reason for quality of teaching and care at schools to be considered below par relative to the returned from country by 4 respondents and better by 2. The mushrooming of and preference for private schooling is also fuelled by a perception of much poor government provided/ public schooling in India relative to countries from where the return migration has taken place in the sample (7 respondents). 5 of these 7 respondents had their children in public schooling when in host (returned from) countries. Relative superior affordability of private schools in India came through as a rationale. However, it then had the element of premium required to get the aspired for quality based on a perception of quality from private schools in host countries. In addition to the premium for top tier private schools being significant - from a purchasing power parity perspective, increased competition to get into good institutions in India also creates a schema, where additional expenses on outside school tutoring was a norm and considered essential for student performance (7 respondents).

Proposition 1: Rationales for return migration from relatively lower development disparity (developed country) settings- associate with a relatively wider choice spectrum in higher disparity context.

Non-resident/ overseas returnee quotas exist in many premier schools with higher fees, and there are also dedicated schools for non- resident/ returnees offering a more aligned syllabus and an aligned peer pool of pupils. There remains the challenge to choose, getting and paying for these options or going for tutoring support to get through private school entrances in the general cohort, without paying excessive fees. For the latter option while adapting to the home country environment is aspired to be fast tracked (3 respondents) the risk of not having the child in a pool of peers with similar overseas educational background also creates issues (4 respondents) in terms of class performance and motivation.

Proposition 2: Choices confronting migrants may require an evaluation of preference between higher convenience vs. faster adaptation.

Both come with risks of negative attainment discrepancy. The choice may require migrant characteristics to be evaluated for determining which is more conducive. For instance, older children with embedded ways of education may have more of a requirement for convenience i.e. require dedicated schools with a peer group of returnees and aligned syllabus with what was in the host country. This was indicated in contrast in responses between 3 respondents with children in 8th to 11th grade vs. others with children in lower than 5th grade.

Financial and asset management

The financial and asset management category is worked in based on services in the area. 18 respondents noted that they had a perception of these to be more customised and personalised in India as an affirmative aspect in rationales. The remaining 4 did not have a view as they were not (yet) drawing on such services in their individual capacity. Interestingly, nearly 16 of the 18 respondents chose services through recommendations and typically, from personally known circles. Of these sixteen, twelve respondents reported a favourable experience or on par with what they had from the returned from country. The remaining 4 and the 2 who sourced services here through web and open advertisements, reported poor experience or negative attainment discrepancy, primarily citing lack of professionalism. For instance, missed deadlines and lack of desired knowledge and expertise.

Proposition 3: Network references in a higher development disparity context reduce the risk of poor choices and consequent negative attainment.

Four respondents had changed accountant/ advisor, and to some extent higher pricing (3 of the 4) did matter for quality that was acceptable. This provides further validation for proposition 1, for premium likely to be coming into effect if benchmarking from a lower development disparity context is applied for in shaping aspirations from choices in a higher disparity context. Overall, 7 respondents noted explicitly that they were advised or experienced that superior pricing mattered in bringing such flexibility to the fore. 10 of the 18 respondents did note very explicitly that they realised in experience the initial the rationale of flexibility of accountants/ advisors. For instance, being available more than would be expected in host/ returned from countries – on weekends and off the cuff non-appointment calls. That country and industry specific cultural attributes will influence attainment levels is quite well acknowledged Wang [37]. There is space to think about what cultural attributes appeal to migrants. How can these be bundled more explicitly into offerings? And what is the cost-benefit trade-off in terms of deploying these attributes for wider and/ or niche market positioning by providers? These are market and policy questions that become useful to ponder over.

Domestic Services

15 of the 21 respondents were very explicit in noting that access to household help without affecting household expenses astronomically was a rationale. 7 of these 15 noted an experience of low reliability of such help; 9 cited overt interference by domestic help and overall, 11 appreciated this as a significant advantage on the balance. 4 of those who had cited issues with domestic help also tried agencies rather than through neighbors but found the experience less than desired. These reverted back to neighborhood recommendations. This provides further validation for proposition 3 in that local/ network references for sourcing services in a high disparity platform may reduce choice-risk. There was positive attainment realised for most of the respondents as per the rationale and realised experience – particularly when drawing on network support.

Health Services

A total of 11 respondents discussed the very reasonably priced health insurance system, with 16 noting that they had one. It was also mentioned by 14 (including the above 11) that the private medical professionals were highly personable- equal to or more than those in host countries. None of the respondents had actually utilised public health services in India (one had tried to access). 2 of the respondents had availed of private health services through health insurance and indicated contrasting experiences, one finding it difficult to negotiate the claim while the other indicated very smooth processing. The difference between the two experiences was noteworthy in two respects: the first was that the respondent with an affirmative experience (positive attainment) did try to deal with a public hospital first before going private with the insurance they had in place. The second was that this respondent with had purchased health insurance based on the reference of a family friend who had the same insurance. This provides validation for proposition 1 and proposition 3: that of premium attached with superior service, in this case, private sector health services becoming apparently preferred when public sector was chosen to be encountered first and recommendations yielding a positive experience.

Private health care in India is availed of by foreign nationals as well not only from developing countries but the developed ones too – frequently labelled ‘health tourism’ both for quality and affordability aspects though overall servicing just 20% of the population Chokshi [38]. The assertions in terms of how health services expectations shaped rationales and the experiences thereof is clearly dominated by the private sector schema. In some ways there are parallels with the education sector marked by similar divide between private and public. Health insurance policy allows access to a range of private hospitals, competing hospitals are increasingly enhancing their act for being on the insurance folio and better rated. Alongside cost considerations in doing so this has to some extent worked in standardising offerings by way of facilities at least within the private sub-sector of health services, particularly in larger cities where the migrant sample was located.

Proposition 4: Institutional protection/ assurance mechanisms have a potential to alleviate risks of negative attainment.

These guarantees resonate with ideas of health, income and education guarantees more successfully executed in developed countries making for lower development disparity. In line with such assertions argued upfront in this paper, these work from the perspective of both pursuing the goal of reduced inequality and attracting return migrants.

Housing and broader Lifestyle aspects

Ten respondents noted that their initial rationale was that while housing is not cheap in urban centres, it does offer quality living at higher price brackets. Based on this they had gone for instalment-based home builds. 7 of these cited less than desirable experience including delays with builders, 2 respondents had similar experience overseas, but both said the experience in India has been more daunting. On transportation the views were mixed but the rationale setting was based on the fact that it would be a challenge and experiences were commensurate. Place of work, family links and education settings related choices were calibrated based on transportation issues, with 9 respondents articulating this very clearly. Respondents were particularly elated about hospitality on holidays they took within the country where pricing was reasonable in terms of facilities they were treated to. 14 of the 21 respondents had taken holidays in the country after return and all agreed on this assertion. 9 of these also made explicit that the experience was superior to what they expected i.e. a positive attainment discrepancy. Respondents however did mention issues with food quality (5 respondents) and safety (9 respondents) in relation to law and order. The former aspect they had encountered and the latter (all 9 respondents) they were conscious of but had not encountered. While housing and lifestyle is a broad church as a category, further introspection of the choices made revealed that overall (for the majority of respondents noting this) that more expensive options particularly when based on network references (for both housing and holidays) yielded superior experiencesclearly in line with propositions 1 and 3.

Discussion

The difference in development disparity may be manifested in dimensions of institutional settings (e.g. health insurance context), agency relationships (e.g. provider attributes across domains discussed), culture specificity (e.g. explicitly noted for financial services) and social network influence (in several instances where network references mattered for attainment). These are also clearly quite integrative as for instance, cultural specificity, agency relationship and network influence come together in forming attainment levels for financial services area, institutional settings and agency relationship are observed quite explicitly for views on the education domain. The bundling also manifests across other domains discussed. These in turn shape attainment discrepancy which can be either positive or negative depending on how the dimensions are managed as noted in the propositions.

At the onset higher development disparity may appear as an advantage from an affordability perspective when the migration is from a lower disparity setting. It is true that migrants can develop strategies to mitigate risks and typically realise upward attainment discrepancy if affordability is very strong. However, the data has shown that often this may not be sufficient by itself, and network references are important to raise or realise on par or superior attainment. The economic and structural rationales and consequences that come forth are quite interwoven as to how development disparity mediates more in the functionalist tradition. The logic of what lies behind sensemaking of attainment discrepancy is relational- and interlinked, and thereby has been argued to be moored in structural functionalism - evidenced in the mediation by difference in development disparity. The paper has contextualised national/country level variation from the perception of migrants to articulate difference in development disparity at play when a congruence between rationales and experiences is sought. From this perspective, it provides an additional vantage point to prior studies on migrant aspirations, that focus on level of aspirations as a function of ‘mental capability’ driven by potential migrants’ characteristics Czakia and Vothknecht [39].

Conclusions

As discussed upfront in contrasting HDI and IHDI [40], a fundamental distinction between developed and developing countries is that of spread in these metrics within a country i.e. the range over which the population lies, and consequent heterogeneity in ‘opportunity’ and ability spaces Sen [3]. Based on the arguments presented, this heterogeneity and its manifestation across institutional, social, agency and cultural dimensions come forth as difference in development disparity. Disparity gives more choices but also poses challenges in linking logics of return migration with aligned consequences. Recognising this mediation explicitly and the ability to deliver considering it is crucial. This is directed not only at the level of return migrants’ sense-making of their decisions but also at policy makers and providers [41].

The policy strategist, in a schema where return migration is strongly argued to need support and encouragement, also needs to reduce development disparity as a larger policy goal -crucial for equitable growth internally and comparative growth relative to countries higher up on the HDI. By extension, to keep return migration attractive, policy focus needs to be on maintaining a spread in choices but also requires dampening any inclination towards dominance of an attitude of leveraging/exploiting difference in development disparity for configuring migrant rationales. While assurance in the health services through the health insurance schema is congruent with both, the affordability premise alone of services may run into a misalignment with equitable development. Migrant rationales pitched on high difference in development disparity alone may also pose very strong challenges on adaptability and convenience parameters as in the case of education. The paper attempts only one lens to reflect on return migration from a difference in development disparity perspective- from developed nations to a developing country. Return migration as a phenomenon across other cross border flows and also, regional and within country boundaries promises research throughput that can matter for policy, industry and for migrants. The conjectures and implications presented here may propel more comprehensive or multiple studies to create a portfolio of useful cues for managing return migration – at the micro level of migrant decisions and for macro level policy strategies.

References

- Banerjee A, Kuri PK (2015) Development Disparities: An Exploration of Past Research. In Development Disparities in India. Springer, New Delhi p. 5-20.

- Inklaar R, Rao DSP (2017) Cross-Country Income Levels over Time: Did the Developing World Suddenly Become Much Richer? American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 9 (1): 265-290.

- Sen A (1993) Markets and freedoms: achievements and limitations of the market mechanism in promoting individual freedoms. Oxford Economic Papers pp. 519-541.

- Foster JE, Lopez‐Calva LF, Szekely M (2005) Measuring the distribution of human development: methodology and an application to Mexico. Journal of Human Development 6(1): 5-25.

- Hicks D A (1997) The inequality-adjusted human development index: a constructive proposal. World development 25(8): 1283-1298.

- Gould JD (1980) European inter-continental emigration. The road home: return migration from the USA. Journal of European Economic History 9(1): 41.

- Dustmann C (1996) Return migration: the European experience. Economic Policy 11(22): 213-250.

- Dahles H (2015) Return Migration as an Engine of Social Change? Reverse Diasporas Capital Investments at Home. In Transnational Agency and Migration. Routledge pp. 77-94.

- Bilgili Ö, Kuschminder K, Siegel M (2017) Return migrants’ perceptions of living conditions in Ethiopia: A gendered analysis. Migration Studies 6(3): 345-366.

- Lowell BL, Findlay A (2001) Migration of highly skilled persons from developing countries: impact and policy responses. International migration papers 44: 25.

- Kahanec M (2013) Labor mobility in an enlarged European Union. International handbook on the economics of migration, Edward Elgar Publishing pp. 137-152.

- Koh SY (2015) State‐led talent return migration programme and the doubly neglected ‘Malaysian diaspora’: Whose diaspora, what citizenship, whose development? Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 36(2): 183-200.

- Setrana MB, Tonah S (2016) Do transnational links matter after return? Labour market participation among Ghanaian return migrants. The Journal of Development Studies 52(4): 549-560.

- Wolff FC (2015) Do the Return Intentions of French Migrants Affect Their Transfer Behaviour? The Journal of Development Studies 51(10): 1358-1373.

- Cerase FP (1974) Expectations and reality: a case study of return migration from the United States to Southern Italy. The International Migration Review 8(2): 245-262.

- Brettell CB, Hollifield JF (2014) Migration theory: Talking across disciplines. Routledge.

- Drori I, Honig B, Wright M (2009) Transnational entrepreneurship: An emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33(5): 1001-1022.

- Al-Ali N, Koser K (2002) Transnationalism, international migration and home. London New York: Routledge.

- Gmelch G (1983) Who returns and why: Return migration behaviour in two North Atlantic societies? Human Organization 42(1): 46-54.

- Kingsbury N, Scanzoni J (2009) Structural-functionalism. In Sourcebook of family theories and methods, Springer US pp. 195-221.

- Hamdouch B, Wahba J (2015) Return migration and entrepreneurship in Morocco. Middle East Development Journal 7(2): 129-148.

- Kubat D (1984) The politics of return. International return migration in Europe. Proceedings of the First European Conference on International Return Migration (November 11-14). Centre of Migration Studies, Rome.

- Constant A, Massey DS (2002) Return migration by German guestworkers: Neoclassical versus new economic theories. International Migration 40(4): 5-38.

- Stark O (1996) On the microeconomics of return migration. In Trade and Development, Palgrave Macmillan: UK p. 32-41.

- Galor O, Stark O (1990) Migrants' savings, the probability of return migration and migrants' performance. International Economic Review 31(2): 463-467.

- Dustmann C (2001) Why Go Back? Return Motives of Migrant Workers. In International Migration: Trends, Policy and Economic Impacts. S. Djajic eds, NY: Routledge pp. 229-249.

- Cassarino Jean-Pierre (2004) The orising return migration: The conceptual approach to return migrants revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies 6(2): 253-279.

- Bijwaard GE, Christian S, Wahba J (2014) The impact of labor market dynamics on the return migration of immigrants. Review of Economics and Statistics 96(3): 483-494.

- Wahba J, Zenou Y (2012) Out of sight, out of mind: Migration, entrepreneurship and social capital. Regional Science and Urban Economics 42(5): 890-903.

- Kırdar MG (2013) Source country characteristics and immigrants’ optimal migration duration decision. IZA Journal of Migration 2(1): 8.

- De Bree J, Davids T, De Haas H (2010) Post‐return experiences and transnational belonging of return migrants: a Dutch-Moroccan case study. Global Networks 10(4): 489-509.

- Handlos L, Neerup, MK, Norredam M (2015) Wellbeing or welfare benefits—what are the drivers for migration? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 44(2): 117-119.

- Cai R, Esipova N, Oppenheimer M, Feng S (2014) International migration desires related to subjective well-being. IZA Journal of Migration 3(1): 8.

- Blanchflower DG, Andrew JO (2011) International happiness: A new view on the measure of performance. The Academy of Management Perspectives 25(1): 6-22.

- Bartram D (2013) Migration, return, and happiness in Romania. European Societies 15(3): 408-422.

- Leinaweaver JB (2014) The Quiet Migration Redux: International Adoption, Race and Difference. Human Organisation 73(1): 62-71.

- Wang DJ (2020) When do return migrants become entrepreneurs? The role of global social networks and institutional distance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 14(2): 125-148.

- Chokshi M, Patil B, Khanna R, Neogi SB, Sharma J, et al. (2016) Health systems in India. Journal of Perinatology 36(3): S9-S12.

- Czaika M, Vothknecht M (2014) Migration and aspirations–are migrants trapped on a hedonic treadmill? IZA Journal of Migration 3(1): 1.

- UNDP (2020) http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/138806.

- Sabharwal M, Varma R (2016) Return Migration to India: Decision‐Making among Academic Engineers and Scientists. International Migration 54(4): 177-190.